The Thrombopoietic Signature of Preeclampsia: Diagnostic and Monitoring Insights from the Immature Platelet Fraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Blood Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Measurement of IPF

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Study Enrollment and Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Comparison of Initial Laboratory Profiles Between Groups

3.3. Treatment-Related Changes in Laboratory Parameters Among Pregnant Women with Preeclampsia

3.4. Severity-Related Differences in Δ Laboratory Parameters in the Preeclampsia Group

3.5. Gestational Age-Based Differences in Δ Laboratory Parameters in Preeclampsia Group

3.6. Logistic Regression Analysis of Parameters Associated with Preeclampsia

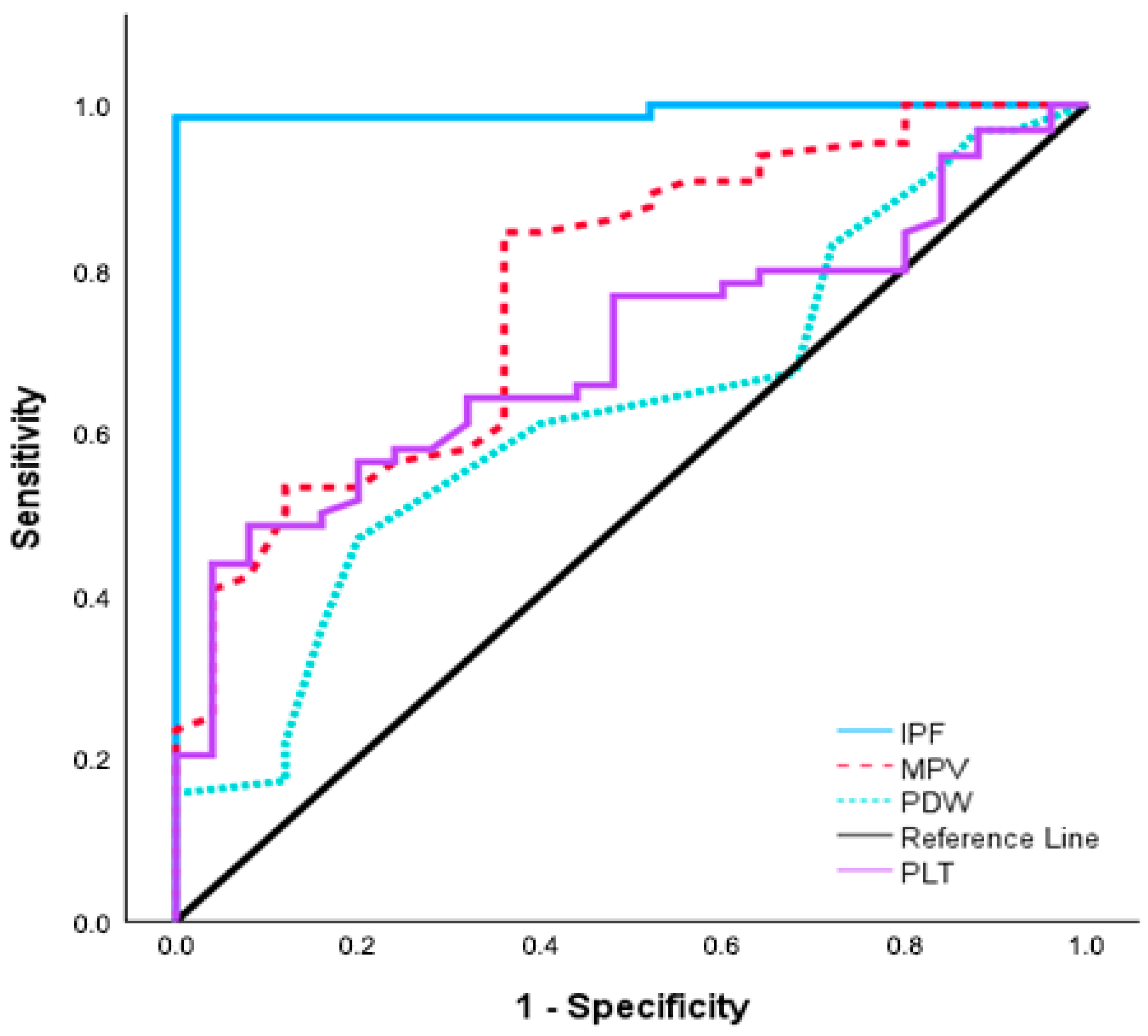

3.7. Diagnostic Performance of Platelet Indices According to ROC Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steegers, E.A.; von Dadelszen, P.; Duvekot, J.J.; Pijnenborg, R. Preeclampsia. Lancet 2010, 376, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomkiewicz, J.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D.A. Biomarkers for Early Prediction and Management of Preeclampsia: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e944104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gathiram, P.; Moodley, J. Pre-eclampsia: Its pathogenesis and pathophysiolgy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, S.E.; Min, J.Y.; Merchan, J.; Lim, K.H.; Li, J.; Mondal, S.; Libermann, T.A.; Morgan, J.P.; Sellke, F.W.; Stillman, I.E.; et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, M.G.; Bevan, S.; Alam, S.; Verghese, L.; Agrawal, S.; Beski, S.; Thuraisingham, R.; MacCallum, P.K. Platelet activation and endogenous thrombin potential in pre-eclampsia. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, e76–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, C.; Larsen, J.B.; Fuglsang, J.; Hvas, A.M. Platelet function in preeclampsia—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Platelets 2019, 30, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundar, O.; Yoruk, P.; Tutuncu, L.; Erikci, A.A.; Muhcu, M.; Ergur, A.R.; Atay, V.; Mungen, E. Longitudinal study of platelet size changes in gestation and predictive power of elevated MPV in development of pre-eclampsia. Prenat. Diagn. 2008, 28, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooh, A.M.; Abdeldayem, H.M. Changes in platelet indices during pregnancy as potential markers for prediction of preeclampsia development. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 5, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, L.M.; Favero, G.M. Platelet indices and angiogenesis markers in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2024, 46, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D.; Munhoz, T.P.; Pinheiro da Costa, B.E.; Hentschke, M.R.; Sontag, F.; Silveira, L.L.; Gadonski, G.; Antonello, I.C.; Poli-de-Figueiredo, C.E. Immature platelet fraction in hypertensive pregnancy. Platelets 2016, 27, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, U.; Kaiser, T.; Stepan, H.; Jank, A. The immature platelet fraction in hypertensive disease during pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D.; Milioni, C.; Vieira, C.F.; Parera, E.A.; Silva, B.D.; Baron, M.V.; Costa, B.E.P.D.; Poli-de-Figueiredo, C.E. Immature Platelet Fraction and Thrombin Generation: Preeclampsia Biomarkers. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2022, 44, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, M.M.; Penfield, C.A.; Hausvater, A.; Schaap, A.; Roman, A.S.; Xia, Y.; Gossett, D.R.; Quinn, G.P.; Berger, J.S. The relationship between platelet indices and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 308, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, e1–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Fenn, S.; Rolnik, D.L.; Mol, B.W.; da Silva Costa, F.; Wallace, E.M.; Palmer, K.R. The impact of the definition of preeclampsia on disease diagnosis and outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 217.e1–217.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera, M.C.; Parant, O.; Vayssiere, C.; Arnal, J.F.; Payrastre, B. Physiologic and pathologic changes of platelets in pregnancy. Platelets 2010, 21, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszala, M.; Poniedziałek-Czajkowska, E.; Mierzynski, R.; Wankowicz, A.; Zamojska, A.; Grzechnik, M.; Golubka, I.; Leszczynska-Gorzelak, B.; Gogacz, M. Thrombocytopenia in pregnant women. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Defining, Establishing, and Verifying Reference Intervals in the Clinical Laboratory; Approved Guideline, 3rd ed.; CLSI document C28-A3; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, C.; Kunka, S.; Hart, D.; Oguni, S.; Machin, S.J. Assessment of an immature platelet fraction (IPF) in peripheral thrombocytopenia. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, L.A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; von Dadelszen, P. Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1817–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.J.; Seow, K.M.; Chen, K.H. Preeclampsia: Recent Advances in Predicting, Preventing, and Managing the Maternal and Fetal Life-Threatening Condition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, K.; Guraslan, H.; Senturk, M.B.; Helvacioglu, C.; Idil, S.; Ekin, M. Can platelet count and platelet indices predict the risk and the prognosis of preeclampsia? Hypertens. Pregnancy 2015, 34, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSheeha, M.A.; Alaboudi, R.S.; Alghasham, M.A.; Iqbal, J.; Adam, I. Platelet count and platelet indices in women with preeclampsia. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2016, 21, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, T.R.; Garner, S.F.; Lees, C.C.; Goodall, A.H. Immature platelet fraction analysis demonstrates a difference in thrombopoiesis between normotensive and preeclamptic pregnancies. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 111, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratsch, U.; Kaiser, T.; Stepan, H.; Jank, A. Evaluation of bone marrow function with immature platelet fraction in normal pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017, 10, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Meena, V.K.; Saluja, S.; Nawal, R.; Verma, A.; Chhabra, V.; Kaushik, K.; Garhwal, M. Immature platelet fraction as a predictive marker of severity in hypertensive disease of pregnancy: A prospective cross-sectional study. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2024, 42, e2023983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, S.; Ranjan, S.; Hoffmann, J.; Kashif, M.; Daniel, E.A.; Al-Dabet, M.M.; Bock, F.; Nazir, S.; Huebner, H.; Mertens, P.R.; et al. Maternal extracellular vesicles and platelets promote preeclampsia via inflammasome activation in trophoblasts. Blood 2016, 128, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayuningsih, C.; Lismayanti, L.; Tjandrawati, A. Comparison of thrombocyte indices and immature platelet between preeclampsia and normal pregnancy. Indones. J. Clin. Pathol. Med. Lab. 2023, 30, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, F.; Negash, M.; Alemu, J.; Yahya, M.; Teklu, G.; Yibrah, M.; Asfaw, T.; Tsegaye, A. Role of platelet parameters in early detection and prediction of severity of preeclampsia: A comparative cross-sectional study at Ayder comprehensive specialized and Mekelle general hospitals, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, M.; Asrie, F.; Gelaw, Y.; Getaneh, Z. The role of platelet parameters for the diagnosis of preeclampsia among pregnant women attending at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital antenatal care unit, Gondar, Ethiopia. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalor, N.; Singh, K.; Pujani, M.; Chauhan, V.; Agarwal, C.; Ahuja, R. A correlation between platelet indices and preeclamsia. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2019, 41, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezuluike, B.S.; Anikwe, C.C.; Nnachi, O.C.; Iwe, B.C.A.; Ifemelumma, C.C.; Dimejesi, I.B.O. Correlation of platelet parameters with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in severe preeclampsia: A case-control study. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unay, D.O.; Ignak, S.; Buyukuysal, M.C. Immature Platelet Count Levels as a Novel Quality Marker in Plateletpheresis. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2018, 34, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpataux, N.; Franke, K.; Kille, A.; Valina, C.M.; Neumann, F.J.; Nührenberg, T.; Hochholzer, W. Reticulated Platelets in Medicine: Current Evidence and Further Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, H.; Herraiz, I.; Schlembach, D.; Verlohren, S.; Brennecke, S.; Chantraine, F.; Klein, E.; Lapaire, O.; Llurba, E.; Ramoni, A.; et al. Implementation of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio for prediction and diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in singleton pregnancy: Implications for clinical practice. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2015, 45, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlohren, S.; Stepan, H.; Dechend, R. Angiogenic growth factors in the diagnosis and prediction of pre-eclampsia. Clin. Sci. 2012, 122, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstein, J.J.; van Runnard Heimel, P.J.; Franx, A.; Lenting, P.J.; Bruinse, H.W.; Silence, K.; de Groot, P.G.; Fijnheer, R. Acute activation of the endothelium results in increased levels of active von Willebrand factor in hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 4, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Preeclampsia Group n = 64 1 | Control Group n = 25 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 31.3 ± 5.0 | 28.4 ± 4.0 | 0.008 & |

| Gestational weeks | 35.2 (26.2–39.6) | 37.4 (34–40.5) | <0.001 * |

| Gravidity | 1 (1–7) | 2 (1–4) | 0.561 * |

| Parity | 0 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | 0.005 * |

| Nulliparous | 36 (56.3) | 11(44) | 0.298 * |

| Previous abortions | 14 (32) | 8 (21.9) | 0.320 * |

| SBP, mmHg | 147.5 (130–180) | 110 (100–120) | <0.001 * |

| DBP, mmHg | 90 (80–117) | 70 (60–80) | <0.001 * |

| Cesarean delivery | 59 (92.2) | 16 (64) | 0.002 * |

| Birth weight, kg | 2442 ± 799 | 2944 ± 419 | <0.001 & |

| Apgar score, 1st min | 8 (3–9) | 8 (7–9) | 0.267 * |

| Apgar score, 5th min | 9 (6–10) | 9 (8–10) | 0.221 * |

| Parameters # | Preeclampsia Group n = 64 1 | Control Group n = 25 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC-1 (×103/μL) | 10.0 (5.8–19.5) | 10.7 (5.1–17.7) | 0.519 * |

| Hb-1 (g/dL) | 11.4 ± 1.2 | 11.4 ± 1.2 | 0.759 & |

| Hct-1 (%) | 34.3 ± 3.5 | 34.5 ± 3.6 | 0.829 & |

| PLT-1 (×103/μL) | 219.5 (120–402) | 275 (176–444) | <0.001 * |

| MPV-1 (fL) | 12.3 ± 1.5 | 10.8 ± 1.1 | 0.004 & |

| PDW-1 (%) | 16.3 (15.6–17.4) | 16.2 (15.6–16.7) | 0.033 * |

| IPF-1 (%) | 8.0 ± 4.8 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | <0.001 & |

| BUN-1 (mg/dL) | 19 (9–38) | 16 (10–24) | 0.069 * |

| Creatinine-1 (mg/dL) | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.066 & |

| ALT-1 (U/L) | 11 (5–128) | 9 (5–18) | 0.140 * |

| AST-1 (U/L) | 17 (5–163) | 15 (10–21) | 0.110 * |

| CRP-1 (mg/L) | 8.2 (0–28.8) | 4.6 (1.4–12.9) | 0.060 * |

| UPC ratio-1 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | - | - |

| Parameters | Preeclampsia Group n = 64 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| WBC-1 | 10.0 (5.8–19.5) | 0.979 ¥ |

| WBC-2 | 10.6 (4.0–19.3) | |

| ΔWBC | −0.27 (−0.21–1.74) | |

| Hb-1 | 11.2 (8.9–14.5) | 0.002 ¥ |

| Hb-2 | 11 (8–13.3) | |

| ΔHb | 0.3 (0.2–1.3) | |

| Hct-1 | 34.2 (27.9–44.9) | 0.003 ¥ |

| Hct-2 | 33 (22.6–81.9) | |

| ΔHct | 1.2 (1.3–37) | |

| PLT-1 | 219.5 (120.0–402.0) | 0.561 ¥ |

| PLT-2 | 223.0 (119.0–395.0) | |

| ΔPLT | −5.800 (−1.350–7.000) | |

| MPV-1 | 12.3 ± 1.5 | <0.001 § |

| MPV-2 | 11.5 ± 1.3 | |

| ΔMPV | 0.83 ± 0.86 | |

| PDW-1 | 16.3 (15.6–17.4) | 0.028 ¥ |

| PDW-2 | 16.2 (15.3–17.1) | |

| ΔPDW | 1.2 (0.3–2.1) | |

| IPF-1 | 8.0 ± 4.8 | <0.001 § |

| IPF-2 | 4.58 | |

| ΔIPF | 3.4 ± 1.7 | |

| BUN-1 | 20 ± 7 | 0.566 § |

| BUN-2 | 21 ± 9 | |

| ΔBUN | −0.5 ± 0.7 | |

| Creatinine-1 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.065 § |

| Creatinine-2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | |

| Δ Creatinine | −0.2 ± 0.5 | |

| ALT-1 | 10.5 (5–128) | 0.046 ¥ |

| ALT-2 | 12 (5–50) | |

| ΔALT | −1.9 (−0.3–70) | |

| AST-1 | 16.5 (5–163) | 0.214 ¥ |

| AST-2 | 19 (5–100) | |

| ΔAST | −2.9 (−1.9–65) | |

| UPC Ratio-1 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 0.005 § |

| UPC Ratio-2 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | |

| ΔUPC Ratio | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| Parameters | Non-Severe Preeclampsia Group, n = 50 1 | Severe Preeclampsia Group, n = 14 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔWBC | −15 (−11.3–8.41) | −535 (−8.2–6.81) | 0.884 ¥ |

| ΔHb | 0.1 (−1.6–2.4) | 0.7 (−0.6–3.1) | 0.095 ¥ |

| ΔHct | 0.25 (−47.9–7.1) | 1.5 (−1.7–9.5) | 0.029 ¥ |

| ΔPLT | −4.5 (−82.7–105) | 7.5 (−27–87) | 0.142 ¥ |

| ΔMPV | 0.69 ± 0.8 | 1.34 ± 0.92 | 0.012 § |

| ΔPDW | 0.1 (−0.9–1.3) | 0.2 (−0.6–1.1) | 0.630 ¥ |

| ΔIPF | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 0.108 § |

| ΔBUN | −0.3 ± 5.6 | −1.3 ± 12.0 | 0.774 § |

| ΔCreatinine | −0.02 (−0.45–0.44) | 0.06 (−1.41–0.13) | 0.196 ¥ |

| ΔALT | −0.5 (−32–6) | 0 (−16–82) | 0.344 ¥ |

| ΔAST | −1.5 (−55–19) | 0.5 (−81–123) | 0.105 ¥ |

| ΔUPC Ratio | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.046 § |

| Parameters | Early Onset Preeclampsia Group, n = 21 1 | Late-Onset Preeclampsia Group, n = 43 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔWBC | 0.46 (−6.9–8.41) | −0.39 (−11.3–7.02) | 0.637 ¥ |

| ΔHb | 0.2 (−0.3–3.1) | 0.1 (−1.6–2.4) | 0.215 ¥ |

| ΔHct | 1.1 (−1.1–9.5) | 0.3 (−47.9–9) | 0.211 ¥ |

| ΔPLT | 224.81 ± 430.76 | −386 ± 240.24 | 0.032 § |

| ΔMPV | 1.16 ± 0.94 | 0.67 ± 0.79 | 0.034 § |

| ΔPDW | 0 (−0.9–0.6) | 0.1 (−0.4–1.3) | 0.106 ¥ |

| ΔIPF | 2.4 (1.5–7.9) | 3.4 (0.6–9.1) | 0.038 ¥ |

| ΔBUN | −1.52 ± 10.62 | −0.05 ± 5.17 | 0.552 § |

| ΔCreatinine | −0.04 (−1.41–0.29) | −0.01 (−0.22–0.44) | 0.520 ¥ |

| ΔALT | −1 (−16–2) | 1 (−32–82) | 0.031 ¥ |

| ΔAST | −1 (−81–5) | −1 (−55–123) | 0.150 ¥ |

| ΔUPC Ratio | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.785 § |

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 1.094 | 0.799 | 1.499 | 0.575 |

| PLT-1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.974 |

| MPV-1 | 1.019 | 0.944 | 1.1 | 0.625 |

| PDW-1 | 0.973 | 0.657 | 1.441 | 0.890 |

| IPF-1 | 27.291 | 2.6 | 86.46 | 0.006 |

| BUN-1 | 1.083 | 0.815 | 1.438 | 0.583 |

| CRP-1 | 1.123 | 0.751 | 1.677 | 0.573 |

| Parameters | Cut-Off | AUC (95% CI) | p-Value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLT-1 | ≤216.5 | 0.697 (0.587–0.806) | <0.001 | 48.4% | 92% |

| MPV-1 | ≥11.1 | 0.775 (0.670–0.880) | <0.001 | 84.4% | 64% |

| PDW-1 | ≥16.4 | 0.625 (0.501–0.749) | 0.047 | 46.9% | 80% |

| IPF-1 | ≥4 | 0.992 (0.975–1.008) | <0.001 | 98.4% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Er, I.; Sentürk, S.; Arpa, M.; Kuruca, N. The Thrombopoietic Signature of Preeclampsia: Diagnostic and Monitoring Insights from the Immature Platelet Fraction. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010044

Er I, Sentürk S, Arpa M, Kuruca N. The Thrombopoietic Signature of Preeclampsia: Diagnostic and Monitoring Insights from the Immature Platelet Fraction. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleEr, Ilkay, Senol Sentürk, Medeni Arpa, and Nalan Kuruca. 2026. "The Thrombopoietic Signature of Preeclampsia: Diagnostic and Monitoring Insights from the Immature Platelet Fraction" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010044

APA StyleEr, I., Sentürk, S., Arpa, M., & Kuruca, N. (2026). The Thrombopoietic Signature of Preeclampsia: Diagnostic and Monitoring Insights from the Immature Platelet Fraction. Diagnostics, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010044