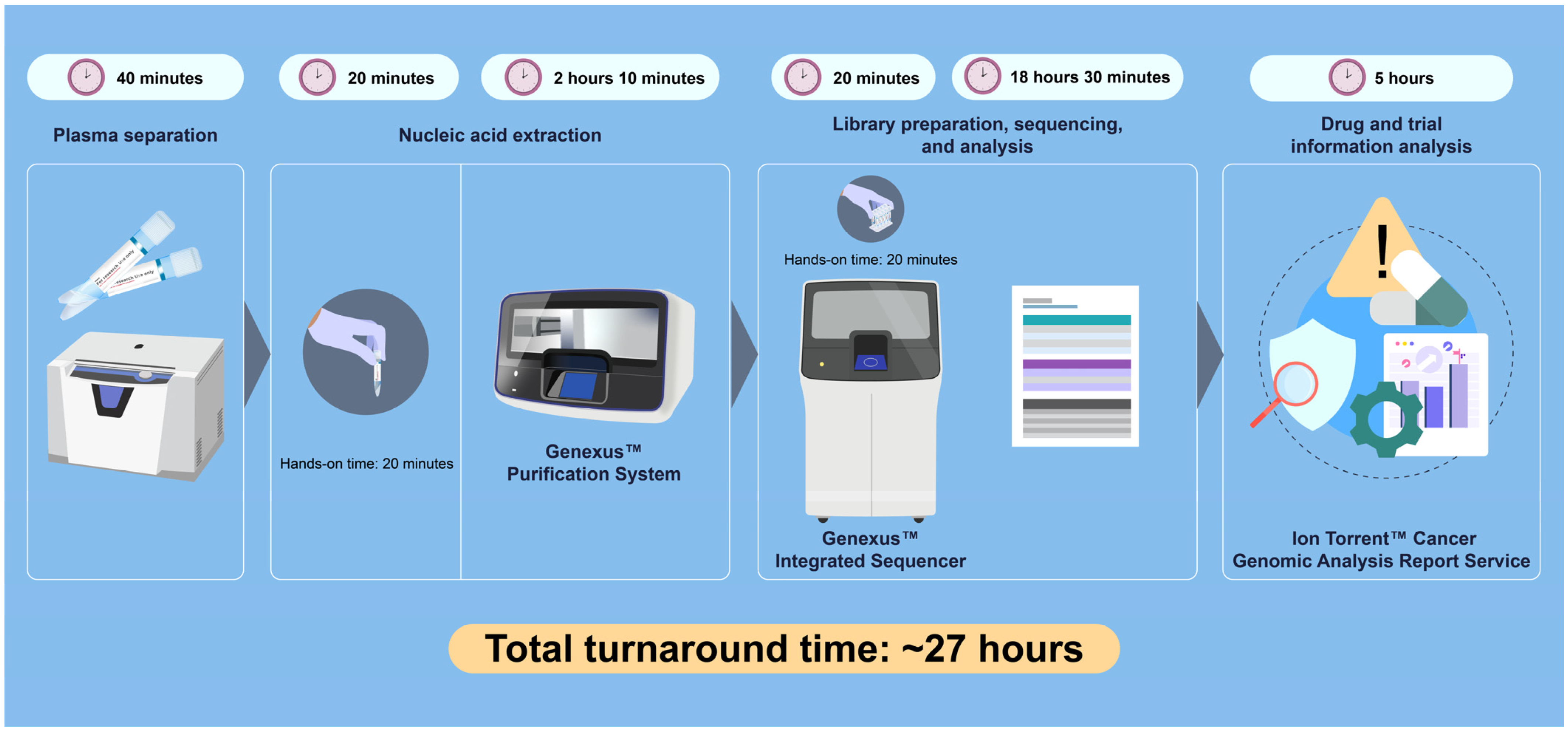

Liquid Biopsy and Automated Next-Generation Sequencing: Achieving Results in 27 Hours Within a Community Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| CNV | Copy number variation |

| dPCR | Digital PCR |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| GX5 | Oncomine Precision Assay GX5 |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| TAT | Turnaround time |

References

- Mateo, J.; Steuten, L.; Aftimos, P.; André, F.; Davies, M.; Garralda, E.; Geissler, J.; Husereau, D.; Martinez-Lopez, I.; Normanno, N.; et al. Delivering precision oncology to patients with cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanno, N.; Machado, J.C.; Pescarmona, E.; Buglioni, S.; Navarro, L.; Esposito Abate, R.; Ferro, A.; Mensink, R.; Lambiase, M.; Lespinet-Fabre, V.; et al. European real-world assessment of the clinical validity of a CE-IVD panel for ultra-fast next-generation sequencing in solid tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behjati, S.; Tarpey, P.S. What is next generation sequencing? Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2013, 98, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, C.; Mack, P.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Aggarwal, C.; Arcila, M.E.; Barlesi, F.; Bivona, T.; Diehn, M.; Dive, C.; Dziadziuszko, R.; et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced NSCLC: A consensus statement from the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.K.; Ariyasu, R.; Uchibori, K.; Hayashi, R.; Chan, H.T.; Chin, Y.M.; Akita, T.; Harutani, Y.; Kiritani, A.; Tsugitomi, R.; et al. Rapid genomic profiling of circulating tumor DNA in non-small cell lung cancer using oncomine precision assay with GenexusTM integrated sequencer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cescon, D.W.; Bratman, S.V.; Chan, S.M.; Siu, L.L. Circulating tumor DNA and liquid biopsy in oncology. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siravegna, G.; Mussolin, B.; Venesio, T.; Marsoni, S.; Seoane, J.; Dive, C.; Papadopoulos, N.; Kopetz, S.; Corcoran, R.B.; Siu, L.L.; et al. How liquid biopsies can change clinical practice in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: Cancer screening and early detection. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Muro, K.; Watanabe, J.; Yamazaki, K.; Ohori, H.; Shiozawa, M.; Takashima, A.; Yokota, M.; Makiyama, A.; Akazawa, N.; et al. Baseline ctDNA gene alterations as a biomarker of survival after panitumumab and chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, B.S.; Beharry, A.; Diep, J.; Perdrizet, K.; Iafolla, M.A.J.; Raskin, W.; Dudani, S.; Brett, M.A.; Starova, B.; Olsen, B.; et al. Point of care molecular testing: Community-based rapid next-generation sequencing to support cancer care. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Takayasu, T.; Zorofchian Moghadamtousi, S.; Arevalo, O.; Chen, M.; Lan, C.; Duose, D.; Hu, P.; Zhu, J.-J.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; et al. Evaluation of the Oncomine Pan-Cancer Cell-Free Assay for analyzing circulating tumor DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with central nervous system malignancies. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arechederra, M.; Rullán, M.; Amat, I.; Oyon, D.; Zabalza, L.; Elizalde, M.; Latasa, M.U.; Mercado, M.R.; Ruiz-Clavijo, D.; Saldaña, C.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of bile cell-free DNA for the early detection of patients with malignant biliary strictures. Gut 2022, 71, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanjo, S.; Wu, W.; Karachaliou, N.; Blakely, C.M.; Suzuki, J.; Chou, Y.T.; Ali, S.M.; Kerr, D.L.; Olivas, V.R.; Shue, J.; et al. Deficiency of the splicing factor RBM10 limits EGFR inhibitor response in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e145099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, F.; Remon, J.; Mateo, J.; Westphalen, C.B.; Barlesi, F.; Lolkema, M.P.; Normanno, N.; Scarpa, A.; Robson, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: A report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J.D.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. (Eds.) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Limited: Chichester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Siepert, N.; Ostrowska, E.; He, L.Q.; Jasti, M.; Lea, K.; Jayaweera, T.; Cheng, A. Abstract 5030: Evaluation of different blood collection tubes for liquid biopsy NGS applications. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tébar-Martínez, R.; Martín-Arana, J.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; Tarazona, N.; Rentero-Garrido, P.; Cervantes, A. Strategies for improving detection of circulating tumor DNA using next generation sequencing. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 119, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gristina, V.; Russo, T.D.B.; Barraco, N.; Gottardo, A.; Pepe, F.; Russo, G.; Fulfaro, F.; Incorvaia, L.; Badalamenti, G.; Troncone, G.; et al. Clinical utility of ctDNA by amplicon based next generation sequencing in first line non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, K.; Chai, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Naeem, R.; Goldstein, D.Y. Clinical validation of the Ion Torrent Oncomine Myeloid Assay GX v2 on the Genexus Integrated Sequencer as a stand-alone assay for single-nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, and fusion genes: Challenges, performance, and perspectives. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 162, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R.; Connolly, A.; Bennett, M.; Hand, C.K.; Burke, L. Implementation of an ISO15189 accredited next-generation sequencing service with the fully automated Ion Torrent Genexus: The experience of a clinical diagnostic laboratory. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 77, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaya, T.; Endo, F.; Takahashi, F.; Tokino, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Nishizuka, S.S. Frequent tumor burden monitoring of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with circulating tumor DNA using individually designed digital polymerase chain reaction. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 463–465.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.; Loree, J.M.; Kasi, P.M.; Parikh, A.R. Using circulating tumor DNA in colorectal cancer: Current and evolving practices. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2846–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidharla, A.; Rapoport, E.; Agarwal, K.; Madala, S.; Linares, B.; Sun, W.; Chakrabarti, S.; Kasi, A. Circulating tumor DNA as a minimal residual disease assessment and recurrence risk in patients undergoing curative-intent resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Zhao, G.; Dai, C. Cell-Free DNA: Plays an essential role in early diagnosis and immunotherapy of pancreatic cancer. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1546332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruban, C.; Bruhm, D.C.; Chen, I.M.; Koul, S.; Annapragada, A.V.; Vulpescu, N.A.; Short, S.; Theile, S.; Boyapati, K.; Alipanahi, B.; et al. Genome-wide analyses of cell-free DNA for therapeutic monitoring of patients with pancreatic cancer. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Fonseca, M.; Brozos-Vázquez, E.; García-Ortiz, M.V.; Costa-Fraga, N.; Díaz-Lagares, Á.; Rodríguez-Ariza, A.; López-López, R.; Aranda, E. Unveiling the potential of liquid biopsy in pancreatic cancer for molecular diagnosis and treatment guidance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 212, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, Y.; Smith, T.; Westfall, J.; Lupo, S. Implementation of cancer next-generation sequencing testing in a community hospital. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2019, 5, a003707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, C.; Beharry, A.; Bendzsak, A.M.; Bisson, K.R.; Dadson, K.; Dudani, S.; Iafolla, M.; Irshad, K.; Perdrizet, K.; Raskin, W.; et al. Point of care liquid biopsy for cancer treatment—Early experience from a community center. Cancers 2024, 16, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, K.E.; Hupel, A.; Mithoowani, H.; Lulic-Kuryllo, T.; Valdes, M. Biomarker turnaround times and impact on treatment decisions in patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma at a large canadian community hospital with an affiliated regional cancer centre. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, M.; Iwaya, T.; Sasaki, N.; Takahashi, F.; Endo, F.; Ishikawa, H.; Okita, Y.; Takahashi, K. Frequent post-operative monitoring of colorectal cancer using individualised ctDNA validated by multiregional molecular profiling. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Iwaya, T.; Yaegashi, M.; Idogawa, M.; Hiraki, H.; Abe, M.; Koizumi, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Yashima-Abo, A.; Fujisawa, R.; et al. Impact of sensitive circulating tumor DNA monitoring on CT scan intervals during postoperative colorectal cancer surveillance. Ann. Surg. Open 2025, 6, e549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.Y.; Nagabhyrava, S.; Ang-Olson, O.; Das, P.; Ladel, L.; Sailo, B.; He, L.; Sharma, A.; Ahuja, N. Translation of epigenetics in cell-free DNA liquid biopsy technology and precision oncology. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6533–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Type | Gene Mutation (Variant) | COSMIC ID | Chromosome Position | Allele Frequency (%) | Copy Number Variation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Plasma (cfDNA, liquid biopsy) | KRAS p.(G12R), c.34G>C | COSM518 | chr12:25398285 | 23.83 | PIK3CA amplification (Copy number: 2.91) |

| TP53 p.(M246I), c.738G>C | COSM10757 | chr17:7577543 | 0.27 | |||

| TP53 p.(M246I), c.738G>A | COSM44310 | chr17:7577543 | 13.89 | |||

| TP53 p.(M246K), c.737T>A | COSM44103 | chr17:7577544 | 31.32 | |||

| GNA11 p.(R183C), c.547C>T | COSM21651 | chr19:3115012 | 0.09 | |||

| Healthy volunteer | Plasma (cfDNA, liquid biopsy) | None detected | – | – | – | None detected |

| Gene Alteration | Therapeutic Agent/Combination | FDA | NCCN | EMA | ESMO | Clinical Trial Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA amplification | Capivasertib + fulvestrant | ● | × | × | × | × |

| Atezolizumab + ipatasertib | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| Temsirolimus | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| Ipatasertib + atezolizumab | × | × | × | × | (I/II) | |

| Palbociclib + gedatolisib | × | × | × | × | (I) | |

| KRAS G12R | Bevacizumab + CAPOX | × | × | × | ● | × |

| Bevacizumab + FOLFIRI | × | × | × | ● | × | |

| Bevacizumab + FOLFOX | × | × | × | ● | × | |

| Bevacizumab + FOLFOXIRI | × | × | × | ● | × | |

| Atezolizumab + cobimetinib | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| Regorafenib + trametinib | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| Selumetinib + durvalumab | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| Ulixertinib + antimalarial | × | × | × | × | (II) | |

| ZEN-3694 + talazoparib | × | × | × | × | (II) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yajima, T.; Hata, F.; Kurokawa, S.; Sawamoto, K.; Yajima, A.; Furuya, D.; Sato, N. Liquid Biopsy and Automated Next-Generation Sequencing: Achieving Results in 27 Hours Within a Community Setting. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010037

Yajima T, Hata F, Kurokawa S, Sawamoto K, Yajima A, Furuya D, Sato N. Liquid Biopsy and Automated Next-Generation Sequencing: Achieving Results in 27 Hours Within a Community Setting. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleYajima, Tomomi, Fumitake Hata, Sei Kurokawa, Kanan Sawamoto, Akiko Yajima, Daisuke Furuya, and Noriyuki Sato. 2026. "Liquid Biopsy and Automated Next-Generation Sequencing: Achieving Results in 27 Hours Within a Community Setting" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010037

APA StyleYajima, T., Hata, F., Kurokawa, S., Sawamoto, K., Yajima, A., Furuya, D., & Sato, N. (2026). Liquid Biopsy and Automated Next-Generation Sequencing: Achieving Results in 27 Hours Within a Community Setting. Diagnostics, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010037