Long-Term Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk in Patients with Pre-Existing Arrhythmia Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

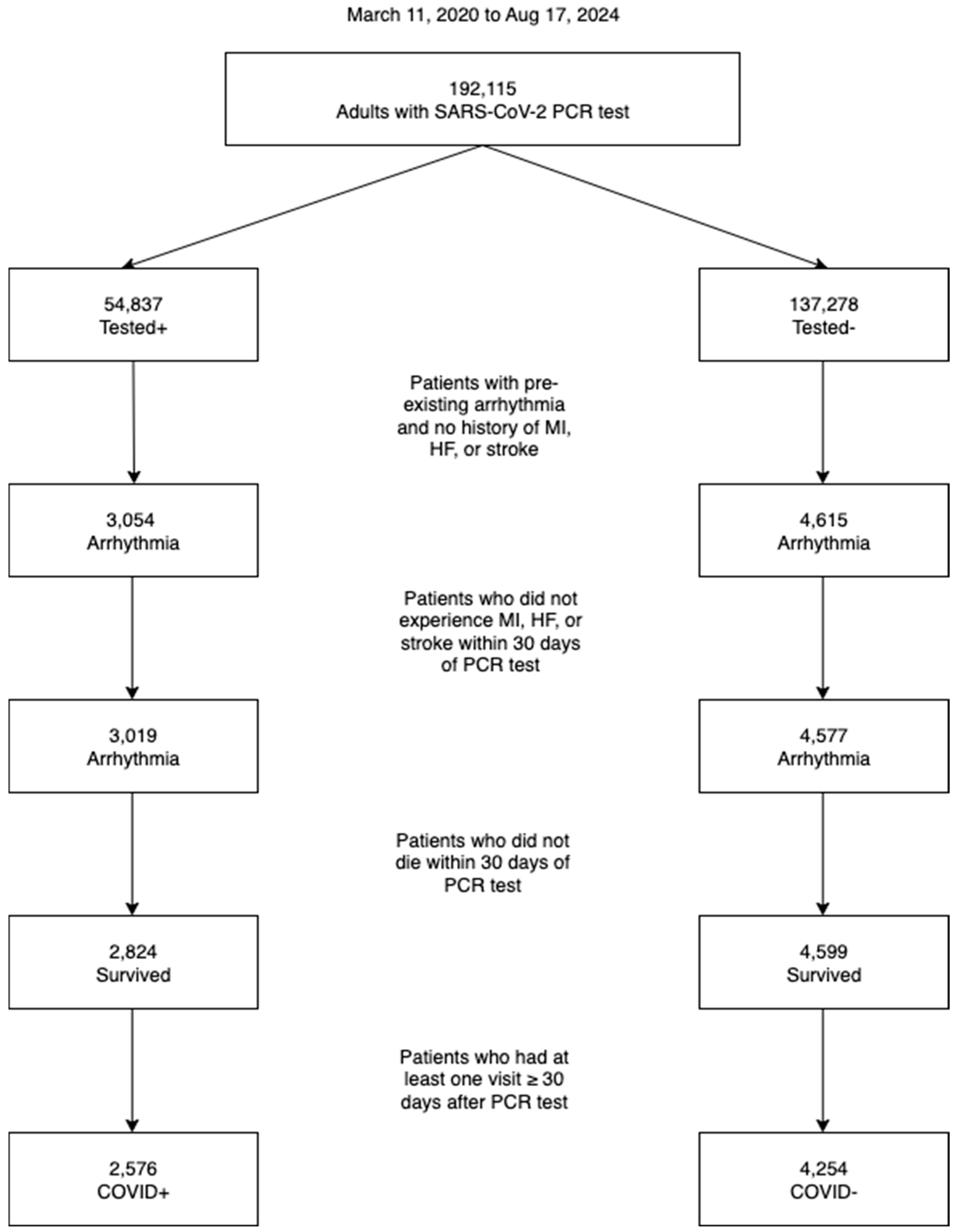

2.2. Study Cohort

2.3. Variables

2.4. Outcome Events

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Selection

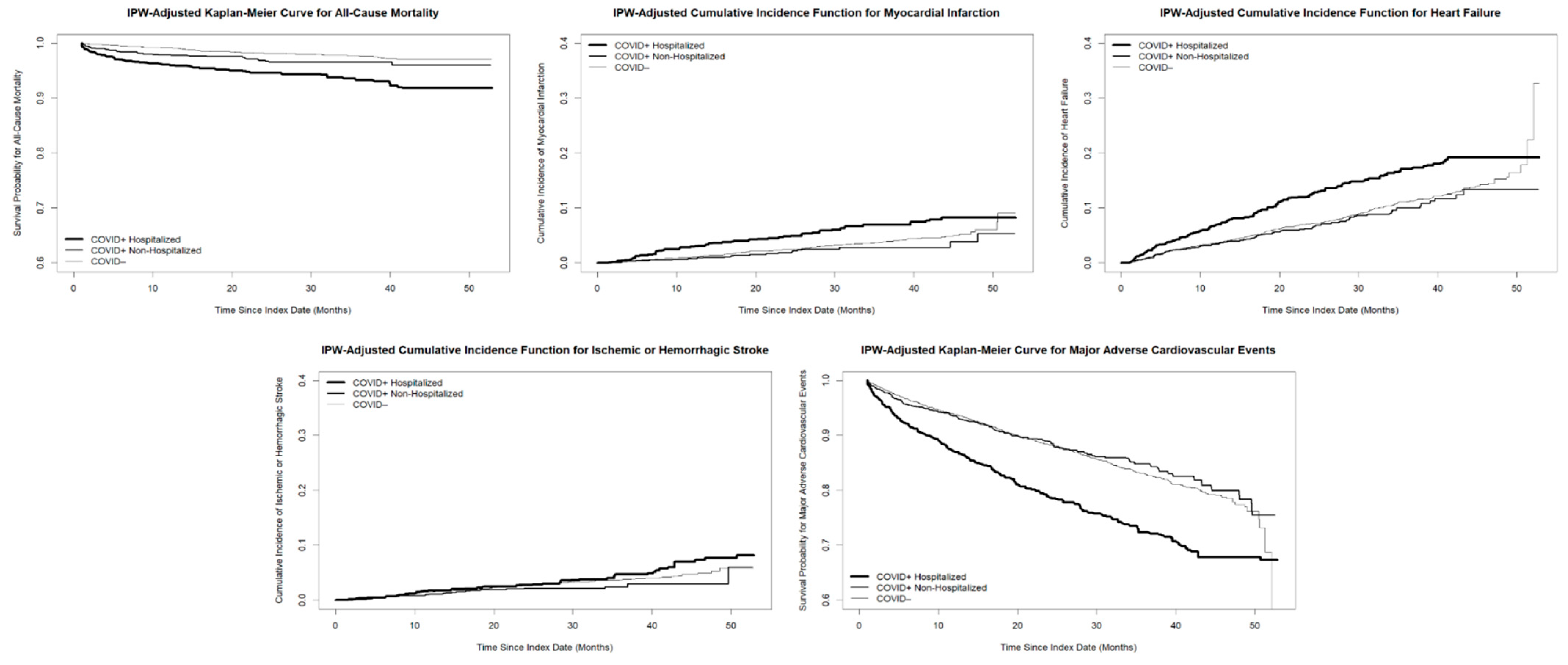

3.2. Main Analysis

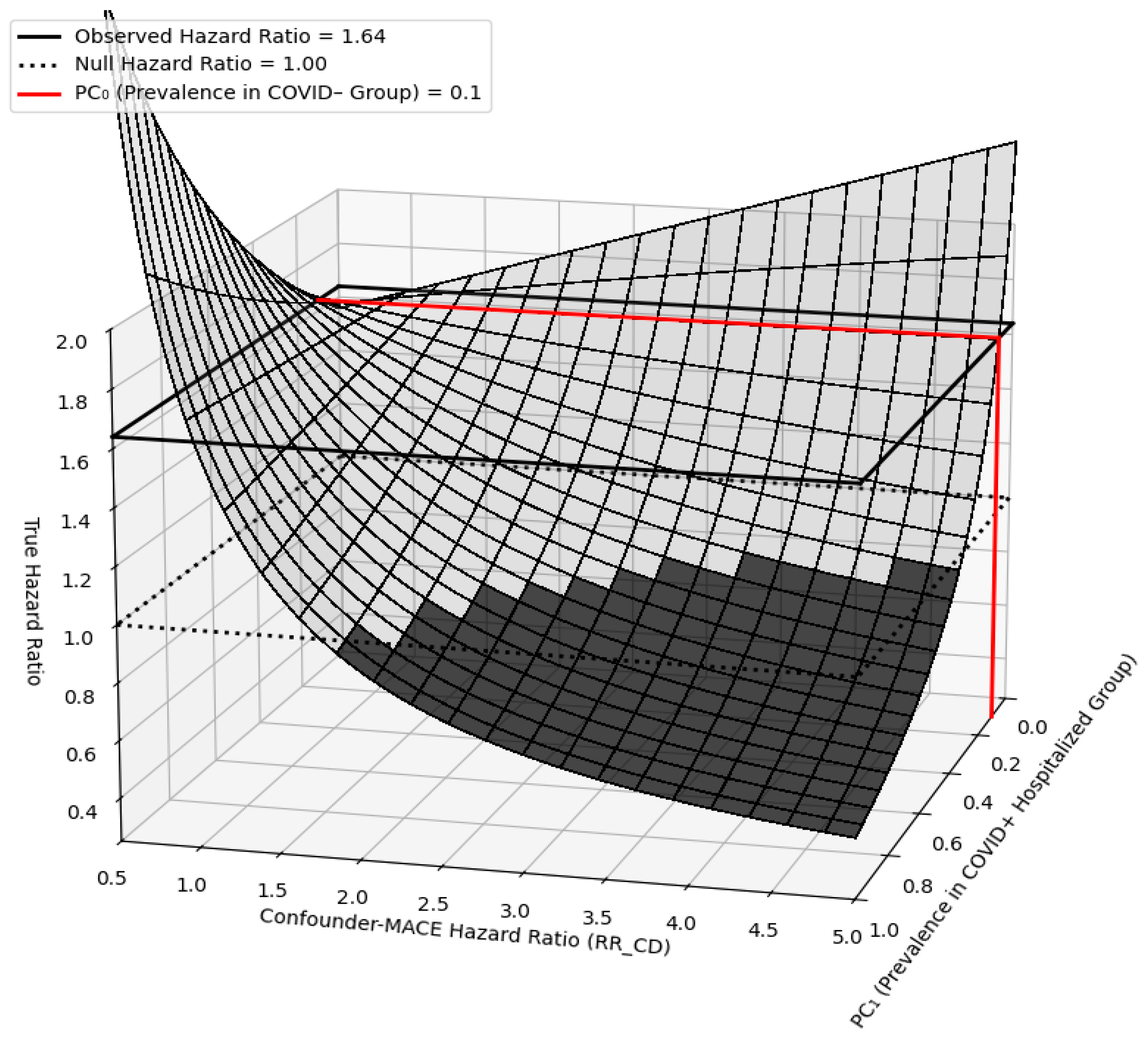

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C., Jr.; Conti, J.B.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014, 130, e199–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khatib, S.M.; Stevenson, W.G.; Ackerman, M.J.; Bryant, W.J.; Callans, D.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Deal, B.J.; Dickfeld, T.; Field, M.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm 2018, 15, e190–e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, D.; Chung, M.K.; Evans, P.T.; Benjamin, E.J.; Helm, R.H. Atrial Fibrillation: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, M.J.; May, H.T.; Bair, T.L.; Crandall, B.G.; Osborn, J.S.; Miller, J.D.; Mallender, C.D.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Anderson, J.L.; Knowlton, K.U.; et al. Atrial fibrillation is a risk factor for major adverse cardiovascular events in COVID-19. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2022, 43, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathannair, R.; Olshansky, B.; Chung, M.K.; Gordon, S.; Joglar, J.A.; Marcus, G.M.; Mar, P.L.; Russo, A.M.; Srivatsa, U.N.; Wan, E.Y.; et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias and Autonomic Dysfunction Associated with COVID-19: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e449–e465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hoang, L.; Aten, K.; Abualfoul, M.; Canela, V.; Prathivada, S.; Vu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Sidhu, M. Mortality and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Hospitalized Patients with Atrial Fibrillation with COVID-19. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 189, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochi, A.N.; Tagliari, A.P.; Forleo, G.B.; Fassini, G.M.; Tondo, C. Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2020, 31, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, P.K.; Freeman, S.V.; Henry, T.D.; Mahmud, E.; Messenger, J.C. Interaction of COVID-19 With Common Cardiovascular Disorders. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, E.J.; Čiháková, D.; Tucker, N.R. Cell-Specific Mechanisms in the Heart of COVID-19 Patients. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhou, K.; Yang, S.; Jia, P. Cardiovascular Manifestations and Mechanisms in Patients with COVID-19. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; Dimarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D’Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: Implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1666–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, K.S.; Henry, S.S.; Duong, T.Q. SARS-CoV-2 infection increases long-term risk of pneumonia in an urban population: An observational cohort study up to 46 months post-infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, K.E.; Lu, J.Y.; Wang, S.; Duong, T.Q. Incidence and risk factors of new clinical disorders in patients with COVID-19 hyperinflammatory syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, K.E.; Henry, S.S.; Cabana, M.D.; Duong, T.Q. Longer-Term Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Asthma Exacerbation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Duong, K.S.; Lu, J.Y.; Chacko, K.R.; Henry, S.; Hou, W.; Fiori, K.P.; Wang, S.H.; Duong, T.Q. Incidence, characteristics, and risk factors of new liver disorders 3.5 years post COVID-19 pandemic in the Montefiore Health System in Bronx. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidchi, R.; Patel, B.; Madan, J.; Liu, A.; Henry, S.; Duong, T.Q. Elevated risk of new-onset chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis up to four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidchi, R.; Ali, E.; Piskun, H.; Henry, S.; Zhang, L.; Duong, T.Q. Elevated Risk of Long-Term Decline in Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction After COVID-19. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e043976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changela, S.; Hadidchi, R.; Wu, S.; Ali, E.; Liu, A.; Peng, T.; Duong, T.Q. Incidence of Anxiety Diagnosis up to Four Years Post SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx and New York. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, W.S.; Pham, A.; Anand, H.; Fleysher, R.; Buczek, A.; Soby, S.; Mirhaji, P.; Yee, J.; Duong, T.Q. Clinical characteristics of the first and second COVID-19 waves in the Bronx, New York: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2021, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; O’Kane, A.M.; Peng, H.; Bi, Y.; Motriuk-Smith, D.; Ren, J. SARS-CoV-2 and cardiovascular complications: From molecular mechanisms to pharmaceutical management. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 114114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Cooper, J.; Salih, A.; Raman, B.; Lee, A.M.; Neubauer, S.; Harvey, N.C.; Petersen, S.E. Cardiovascular disease and mortality sequelae of COVID-19 in the UK Biobank. Heart 2022, 109, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, S.I.; Wei, J.C. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 53, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintore, C.; Cuartero, J.; Camps-Vilaro, A.; Subirana; Elosua, R.; Marrugat, J.; Degano, I.R. Increased risk of arrhythmias, heart failure, and thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals persists at one year post-infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 24, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, V.; Radenkovic, D.; Radenkovic, G.; Djordjevic, V.; Banach, M. Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 575600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Metaxaki, M.; Sithole, N.; Landin, P.; Martin, P.; Salinas-Botran, A. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19: A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parotto, M.; Gyongyosi, M.; Howe, K.; Myatra, S.N.; Ranzani, O.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Herridge, M.S. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: Understanding and addressing the burden of multisystem manifestations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustino, G.; Pinney, S.P.; Lala, A.; Reddy, V.Y.; Johnston-Cox, H.A.; Mechanick, J.I.; Halperin, J.L.; Fuster, V. Coronavirus and Cardiovascular Disease, Myocardial Injury, and Arrhythmia: JACC Focus Seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezache, L.; Soltisz, A.; Tili, E.; Nuovo, G.J.; Veeraraghavan, R. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-induced inflammation underlies proarrhythmia in COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dherange, P.; Lang, J.; Qian, P.; Oberfeld, B.; Sauer, W.H.; Koplan, B.; Tedrow, U. Arrhythmias and COVID-19: A Review. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2020, 6, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Laghi-Pasini, F.; Boutjdir, M.; Capecchi, P.L. Cardioimmunology of arrhythmias: The role of autoimmune and inflammatory cardiac channelopathies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkireddy, D.R.; Chung, M.K.; Gopinathannair, R.; Patton, K.K.; Gluckman, T.J.; Turagam, M.; Cheung, J.W.; Patel, P.; Sotomonte, J.; Lampert, R.; et al. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, e233–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keturakis, V.; Narauskaite, D.; Balion, Z.; Gecys, D.; Kulkoviene, G.; Kairyte, M.; Zukauskaite, I.; Benetis, R.; Stankevicius, E.; Jekabsone, A. The Effect of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein RBD-Epitope on Immunometabolic State and Functional Performance of Cultured Primary Cardiomyocytes Subjected to Hypoxia and Reoxygenation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidchi, R.; Lee, P.; Qiu, S.; Changela, S.; Henry, S.; Duong, T.Q. Long-term outcomes of patients with pre-existing coronary artery disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 2025, 116, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra-Varma, S.; Lu, J.Y.; Boparai, M.S.; Henry, S.; Wang, S.H.; Duong, T.Q. Patients with type 1 diabetes are at elevated risk of developing new hypertension, chronic kidney disease and diabetic ketoacidosis after COVID-19: Up to 40 months’ follow-up. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 5368–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.Y.; Mehrotra-Varma, S.; Wang, S.H.; Boparai, M.S.; Henry, S.; Mehrotra-Varma, J.; Duong, T.Q. Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Are at Greater Risk of Developing New Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease Following COVID-19. J. Diabetes Res. 2025, 2025, 8816198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Boparai, M.S.; Shi, C.; Henninger, E.M.; Rangareddy, M.; Veeraraghavan, S.; Mirhaji, P.; Fisher, M.C.; Duong, T.Q. Long-term outcomes of COVID-19 survivors with hospital AKI: Association with time to recovery from AKI. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Lu, J.Y.; Wang, S.; Duong, K.S.; Henry, S.; Fisher, M.C.; Duong, T.Q. Long term outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease after COVID-19 in an urban population in the Bronx. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.S.; Wang, S.H.; Hou, W.; Duong, T.Q. Incidence rate and risk factors of pulmonary conditions three years post COVID-19 in Bronx, New York: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra-Varma, J.; Kumthekar, A.; Henry, S.; Fleysher, R.; Hou, W.; Duong, T.Q. Hospitalization, Critical Illness, and Mortality Outcomes of COVID-19 in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023, 5, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, Z.; Ptaszek, L.M. Global disparities in arrhythmia care: Mind the gap. Heart Rhythm O2 2022, 3, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Jiang, C.; He, L.; Gao, M.; Tang, R.; Liu, N.; Zhou, N.; Sang, C.; Long, D.; Du, X.; et al. Association between cardiometabolic comorbidity and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlyarov, S.; Lyubavin, A. Structure of Comorbidities and Causes of Death in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z.; Leung, L.W.; Kontogiannis, C.; Chung, I.; Bin Waleed, K.; Gallagher, M.M. Arrhythmias in Chronic Kidney Disease. Eur. Cardiol. 2022, 17, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Nizam, A.; Barker, J.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Koya, A.; Lau, E.Y.M.; Zakkar, M.; Somani, R.; et al. Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation: Bridging the Gap Between Mechanisms, Risk, and Therapy. Medicina 2025, 61, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleg, J.L.; Forman, D.E.; Berra, K.; Bittner, V.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Chen, M.A.; Cheng, S.; Kitzman, D.W.; Maurer, M.S.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 128, 2422–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, J.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Warnqvist, A.; Habel, H.; Skoglund, P.H.; Sundstrom, J.; Hambraeus, K.; Jernberg, T.; Svensson, P. Socioeconomic Disparities and Mediators for Recurrent Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events After a First Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2023, 148, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Sainbayar, E.; Pham, H.N.; Shahid, M.; Saleh, A.A.; Javed, Z.; Khan, S.U.; Al-Kindi, S.; Nasir, K. Social Vulnerability Index and Cardiovascular Disease Care Continuum: A Scoping Review. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Ramireddy, A.; Otalvaro, L.; Forman, D.E. Secondary cardiovascular prevention in older adults: An evidence based review. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Desvigne-Nickens, P.; Alonso, A.; Djousse, L.; Forman, D.E.; Gillis, A.M.; Hendriks, J.M.L.; Hills, M.T.; Kirchhof, P.; et al. Research Priorities in the Secondary Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation: A National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Virtual Workshop Report. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułach, A.; Kucio, M.; Majewski, M.; Gąsior, Z.; Smolka, G. 24 h Holter Monitoring and 14-Day Intermittent Patient-Activated Heart Rhythm Recording to Detect Arrhythmias in Symptomatic Patients after Severe COVID-19—A Prospective Observation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| COVID-19+ (n = 2576) | COVID-19− (n = 4254) | p Value | SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-Up Time (Months), mean ± SD | 23.66 ± 13.79 | 28.81 ± 14.23 | <0.005 | 0.37 |

| Age at Index Date (Years), mean ± SD | 63.49 ± 17.08 | 60.74 ± 16.63 | <0.005 | 0.16 |

| Female, n (%) | 1544 (59.94%) | 2506 (58.91%) | 0.42 | 0.021 |

| Race and Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 327 (12.69%) | 631 (14.83%) | 0.015 | 0.062 |

| Black | 890 (34.55%) | 1481 (34.81%) | 0.84 | 0.0056 |

| Asian | 87 (3.38%) | 133 (3.13%) | 0.62 | 0.014 |

| Other Race | 1272 (49.38%) | 2009 (47.23%) | 0.089 | 0.043 |

| Hispanic | 1100 (42.70%) | 1682 (39.54%) | 0.011 | 0.064 |

| Pre-Existing Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Arrhythmia | 2576 (100.00%) | 4254 (100.00%) | 0 | |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 715 (27.76%) | 983 (23.11%) | <0.005 | 0.11 |

| Atrial Flutter | 141 (5.47%) | 145 (3.41%) | <0.005 | 0.1 |

| Conduction Disease | 735 (28.53%) | 1089 (25.60%) | 0.0086 | 0.066 |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | 145 (5.63%) | 187 (4.40%) | 0.025 | 0.057 |

| Bradyarrhythmia | 1001 (38.86%) | 1728 (40.62%) | 0.16 | 0.036 |

| SVT | 280 (10.87%) | 331 (7.78%) | <0.005 | 0.11 |

| Nonspecific/Misc Arrhythmia | 431 (16.73%) | 649 (15.26%) | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 533 (20.69%) | 659 (15.49%) | <0.005 | 0.14 |

| Hypertension | 1945 (75.50%) | 2909 (68.38%) | <0.005 | 0.16 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 1029 (39.95%) | 1297 (30.49%) | <0.005 | 0.20 |

| COPD | 201 (7.80%) | 189 (4.44%) | <0.005 | 0.14 |

| Asthma | 681 (26.44%) | 906 (21.30%) | <0.005 | 0.12 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 696 (27.02%) | 724 (17.02%) | <0.005 | 0.24 |

| Liver Disease | 375 (14.56%) | 505 (11.87%) | <0.005 | 0.079 |

| Obesity | 1502 (58.31%) | 2274 (53.46%) | <0.005 | 0.098 |

| Tobacco Use | 1067 (41.42%) | 1751 (41.16%) | 0.85 | 0.0053 |

| Insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Medicaid | 718 (27.87%) | 1231 (28.94%) | 0.36 | 0.024 |

| Medicare | 846 (32.84%) | 1167 (27.43%) | <0.005 | 0.12 |

| Private | 894 (34.70%) | 1649 (38.76%) | <0.005 | 0.084 |

| Uninsured | 118 (4.58%) | 207 (4.87%) | 0.63 | 0.013 |

| Income Group, n (%) | ||||

| Lower Third | 1025 (39.79%) | 1636 (38.46%) | 0.29 | 0.027 |

| Middle Third | 803 (31.17%) | 1234 (29.01%) | 0.062 | 0.047 |

| Top Third | 748 (29.04%) | 1384 (32.53%) | <0.005 | 0.076 |

| Unmet Social Needs, n (%) | ||||

| At Least One Unmet Social Need | 269 (10.44%) | 424 (9.97%) | 0.56 | 0.016 |

| No Unmet Social Needs | 790 (30.67%) | 1239 (29.13%) | 0.19 | 0.034 |

| Status Unknown | 1517 (58.89%) | 2591 (60.91%) | 0.10 | 0.041 |

| Hospitalized Due to COVID-19, n (%) | 985 (38.24%) | 0 (0.00%) | <0.005 | 1.10 |

| Vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2, n (%) | 1048 (40.68%) | 1298 (30.51%) | <0.005 | 0.21 |

| Outcomes, n (%) | ||||

| All-Cause Mortality | 116 (4.50%) | 78 (1.83%) | <0.005 | 0.15 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 93 (3.61%) | 122 (2.87%) | 0.10 | 0.042 |

| Heart Failure | 260 (10.09%) | 356 (8.37%) | 0.018 | 0.060 |

| Ischemic or Hemorrhagic Stroke | 74 (2.87%) | 122 (2.87%) | 1.00 | 0.00029 |

| MACE | 433 (16.81%) | 553 (13.00%) | <0.005 | 0.11 |

| (A) Multivariate Regression | ||||

| Outcome | COVID-19+ Hospitalized vs. COVID-19− | COVID-19+ Non-Hospitalized vs. COVID-19− | ||

| Adjusted HR [95% CI] | p Value | Adjusted HR [95% CI] | p Value | |

| All-Cause Mortality | 2.90 [2.08, 4.04] | <0.005 | 1.67 [1.13, 2.47] | 0.010 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1.57 [1.14, 2.17] | 0.0060 | 0.82 [0.55, 1.23] | 0.34 |

| Heart Failure | 1.51 [1.24, 1.84] | <0.005 | 0.94 [0.75, 1.18] | 0.62 |

| Stroke | 1.24 [0.87, 1.78] | 0.24 | 0.83 [0.55, 1.24] | 0.36 |

| MACE | 1.64 [1.40, 1.91] | <0.005 | 0.99 [0.83, 1.18] | 0.92 |

| (B) Inverse Probability Weighting-Adjusted | ||||

| Outcome | COVID-19+ Hospitalized vs. COVID-19− | COVID-19+ Non-Hospitalized vs. COVID-19− | ||

| HR [95% CI] | pValue | HR [95% CI] | pValue | |

| All-Cause Mortality | 3.02 [2.12, 4.30] | <0.005 | 1.65 [1.11, 2.45] | 0.013 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1.74 [1.21, 2.49] | <0.005 | 0.75 [0.49, 1.15] | 0.18 |

| Heart Failure | 1.55 [1.24, 1.93] | <0.005 | 0.91 [0.73, 1.15] | 0.45 |

| Stroke | 1.21 [0.83, 1.77] | 0.32 | 0.75 [0.50, 1.14] | 0.18 |

| MACE | 1.68 [1.40, 2.01] | <0.005 | 0.96 [0.80, 1.15] | 0.66 |

| Biomarker Predictor | IPW-Adjusted HR [95% CI] | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Aspartate Aminotransferase ≥ 100 U/L (n = 946) | 1.05 [0.66, 1.67] | 0.83 |

| C-Reactive Protein ≥ 15 mg/dL (n = 708) | 1.33 [0.96, 1.83] | 0.084 |

| Creatinine ≥ 1.1 mg/dL (n = 979) | 1.47 [1.07, 2.01] | 0.017 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase ≥ 400 U/L (n = 910) | 1.41 [1.01, 1.97] | 0.044 |

| Ferritin ≥ 700 µg/L (n = 640) | 1.09 [0.77, 1.53] | 0.64 |

| D-dimer ≥ 1.5 µg/mL (n = 641) | 1.45 [1.07, 1.94] | 0.015 |

| Hemoglobin ≤ 9.2 g/dL (n = 982) | 2.03 [1.53, 2.69] | <0.005 |

| Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio ≥ 10 (n = 982) | 1.29 [1.00, 1.66] | 0.050 |

| B-type Natriuretic Peptide ≥ 100 pg/mL (n = 212) | 0.88 [0.47, 1.65] | 0.69 |

| Troponin I > 0.20 ng/mL or Troponin T > 0.05 ng/mL (n = 876) | 1.61 [0.79, 3.28] | 0.19 |

| LVEF <50% (n = 212) | 2.71 [1.40, 5.25] | <0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pahuja, S.; Hadidchi, R.; Tonge, J.; Henry, S.; Duong, T.Q. Long-Term Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk in Patients with Pre-Existing Arrhythmia Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010038

Pahuja S, Hadidchi R, Tonge J, Henry S, Duong TQ. Long-Term Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk in Patients with Pre-Existing Arrhythmia Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010038

Chicago/Turabian StylePahuja, Suhani, Roham Hadidchi, Janhavi Tonge, Sonya Henry, and Tim Q. Duong. 2026. "Long-Term Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk in Patients with Pre-Existing Arrhythmia Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010038

APA StylePahuja, S., Hadidchi, R., Tonge, J., Henry, S., & Duong, T. Q. (2026). Long-Term Cardiovascular and Mortality Risk in Patients with Pre-Existing Arrhythmia Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diagnostics, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010038