Evaluation of OCT Angiography Parameters as Biomarkers for Glaucoma Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- “Outside normal limits” on the Glaucoma Hemifield Test;

- Three or more abnormal points with p < 0.05 and at least one with p < 0.01 on the pattern deviation plot; or

- A pattern standard deviation with p < 0.05 confirmed on two consecutive reliable tests (fixation losses ≤ 20% and false-positive and false-negative rates ≤ 25%).

2.2. Ophthalmologic Examination

- detailed ocular and systemic history;

- best-corrected visual acuity for each eye;

- Goldmann applanation tonometry;

- indirect ophthalmoscopy;

- gonioscopy with a Goldmann lens;

- pachymetry;

- SAP;

- OCT.

2.3. Standard Automated Perimetry

2.4. Optical Coherence Tomography and OCT Angiography

- peripapillary VD—PP-VD;

- parafoveal VD—PF-VD;

- foveal avascular zone (FAZ)

- FD-300 (VD in a 300-µm annulus surrounding the FAZ).

2.5. Justification of Follow-Up Interval

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

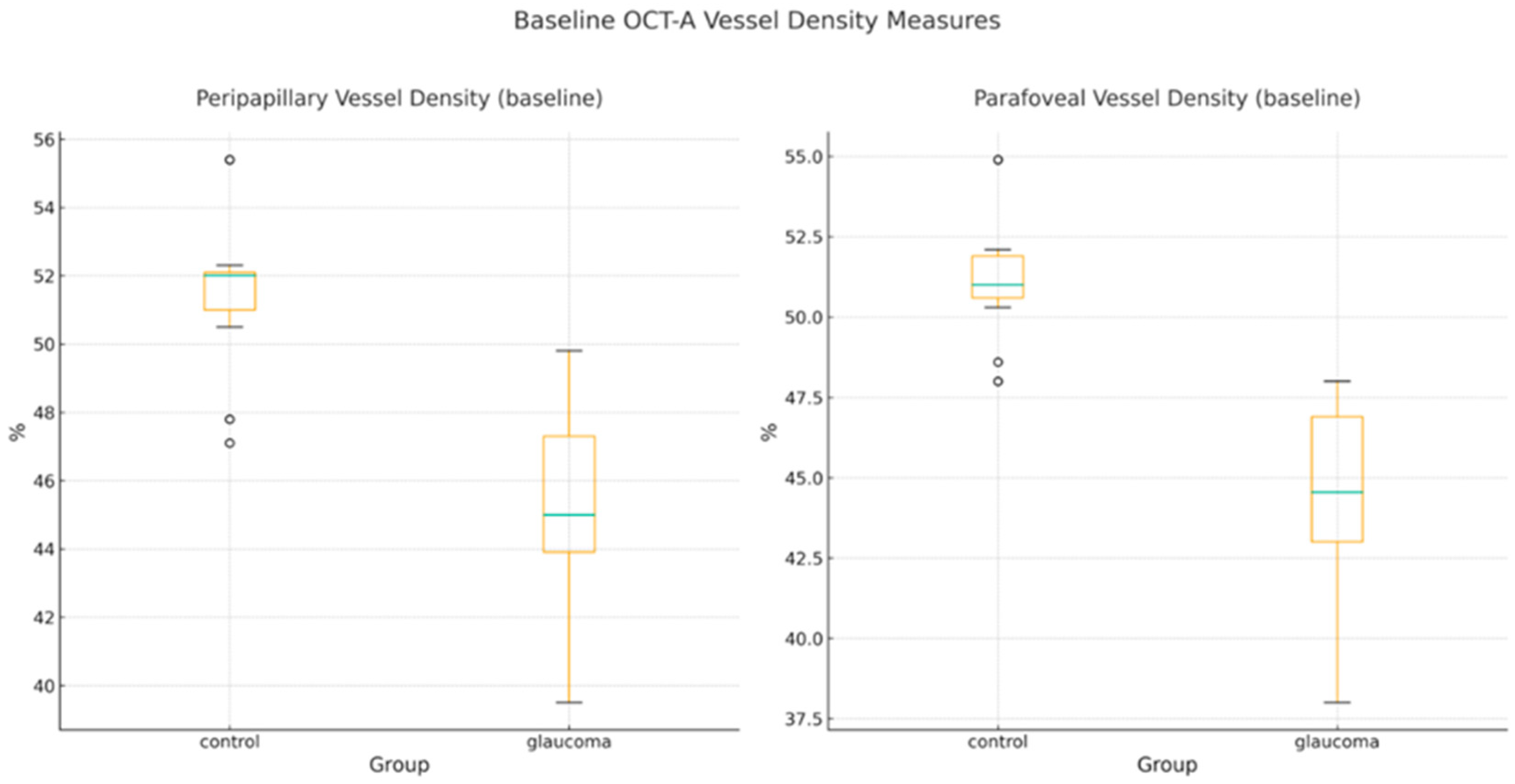

- Baseline OCT-A and Structural Parameters

- 2.

- Six-Month Changes in Structural and OCT-A Parameters

- -

- RNFL thickness decreased by 1.04 µm in glaucoma eyes versus 0.22 µm in controls (between-group Δ difference: −0.82 µm; 95% CI, −1.28 to −0.36; d = 0.94).

- -

- MD declined modestly in glaucoma eyes (Δ = −0.10 dB), while controls showed slight improvement (Δ = +0.06 dB). The between-group difference of −0.16 dB (95% CI, −0.26 to −0.06; d = 0.81) was statistically significant.

- -

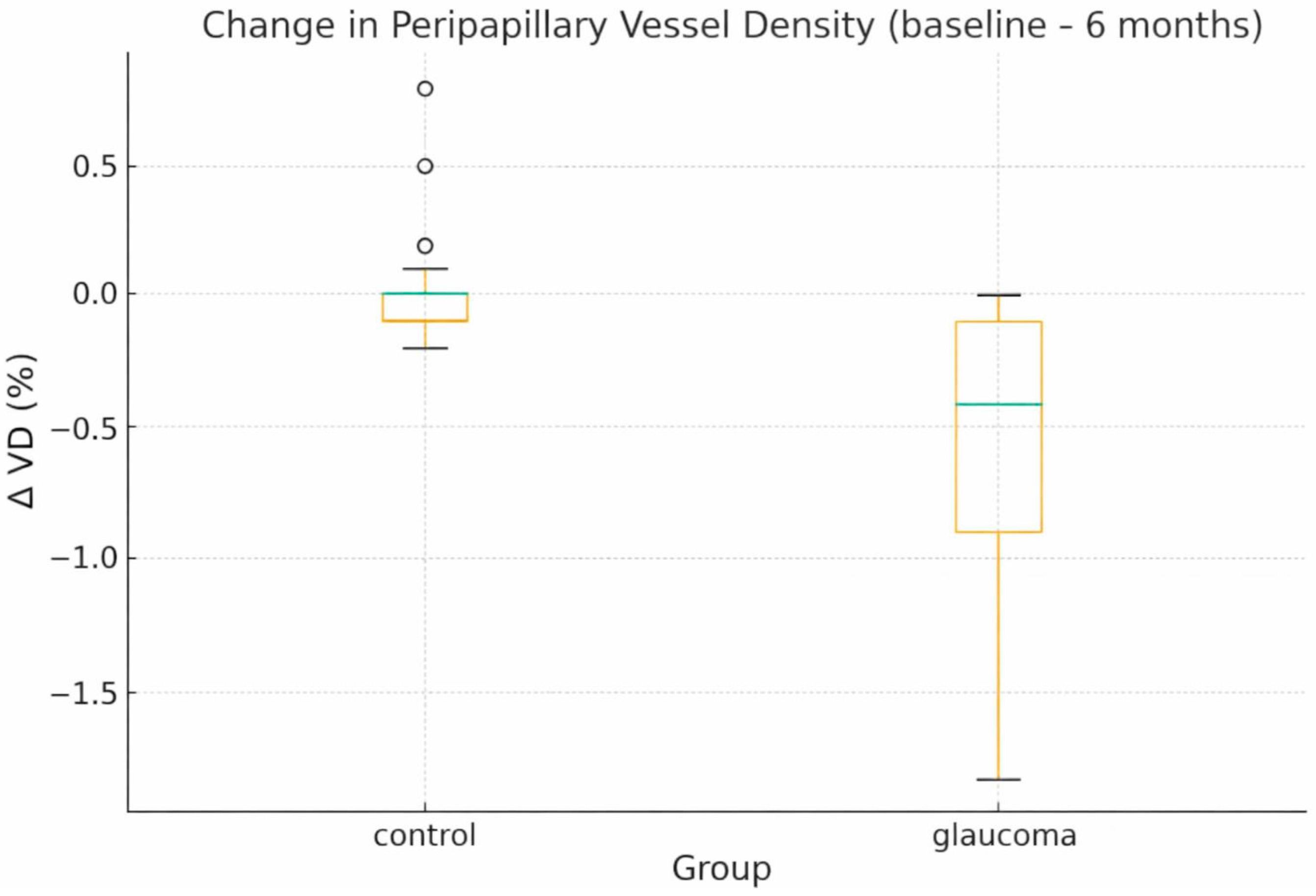

- PP-VD decreased by 0.57% in glaucoma eyes, whereas controls remained essentially stable (Δ = +0.02%). The between-group Δ difference was −0.59% (95% CI, −0.81 to −0.37; d = 1.41), and individual values are depicted in Figure 2.

- -

- Changes in PF and whole-RPC VD were more variable and did not differ significantly between groups, consistent with their broader baseline variance.

- 3.

- ANCOVA Adjusted Six-Month Outcomes

- 4.

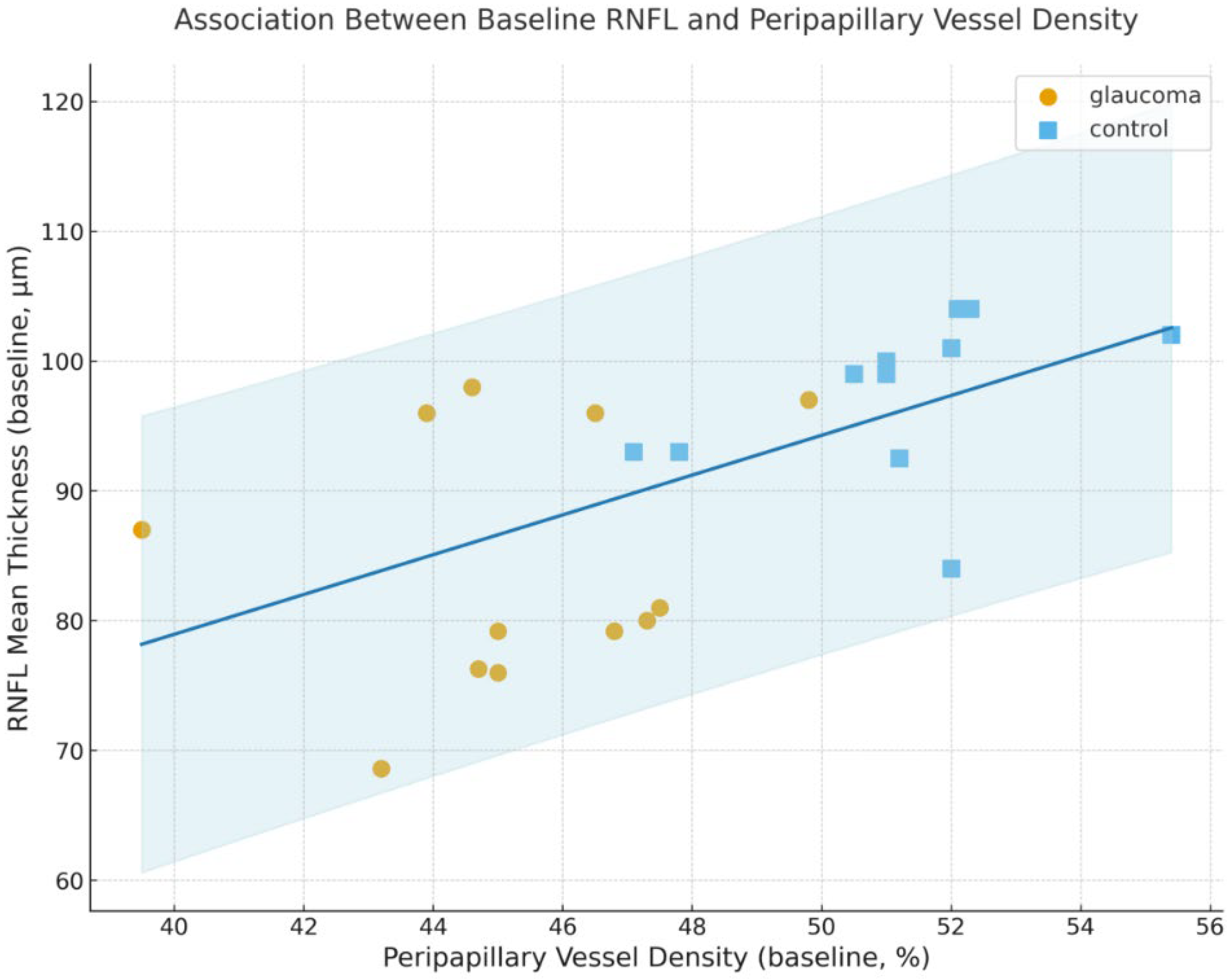

- Relationship Between Structural and Vascular Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinreb, R.N.; Aung, T.; Medeiros, F.A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovitch-Verbin, H. Retinal ganglion cell apoptotic pathway in glaucoma: Initiating and downstream mechanisms. Prog. Brain Res. 2015, 220, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammer, J. The vascular concept of glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1994, 38, S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaranta, L.; Katsanos, A.; Russo, A.; Riva, I. 24-hour intraocular pressure and ocular perfusion pressure in glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2013, 58, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammer, J.; Konieczka, K.; Flammer, A.J. The Role of Ocular Blood Flow in the Pathogenesis of Glaucomatous Damage. US Ophthalmic Rev. 2011, 4, 84–87. Available online: https://glaucomaresearch.ch/pdf/5.E.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.; Yu, M.; Weinreb, R.N.; Ye, C.; Liu, S.; Lai, G.; Lam, D.S. Retinal nerve fiber layer imaging with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: A prospective analysis of age-related loss. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarmohammadi, A.; Zangwill, L.M.; Diniz-Filho, A.; Suh, M.H.; Yousefi, S.; Saunders, L.J.; Belghith, A.; Manalastas, P.I.; Medeiros, F.A.; Weinreb, R.N. Relationship between Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density and Severity of Visual Field Loss in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, Y.; Morrison, J.C.; Tokayer, J.; Tan, O.; Lombardi, L.; Baumann, B.; Lu, C.D.; Choi, W.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Huang, D. Quantitative OCT angiography of optic nerve head blood flow. Biomed. Opt. Express 2012, 3, 3127–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, Y.; Tan, O.; Tokayer, J.; Potsaid, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.J.; Kraus, M.F.; Subhash, H.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Hornegger, J.; et al. Split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography with optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 4710–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yarmohammadi, A.; Zangwill, L.M.; Diniz-Filho, A.; Suh, M.H.; Manalastas, P.I.; Fatehee, N.; Yousefi, S.; Belghith, A.; Saunders, L.J.; Medeiros, F.A.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density in Healthy, Glaucoma Suspect, and Glaucoma Eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, OCT451–OCT459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rao, H.L.; Pradhan, Z.S.; Weinreb, R.N.; Reddy, H.B.; Riyazuddin, M.; Dasari, S.; Palakurthy, M.; Puttaiah, N.K.; Rao, D.A.; Webers, C.A. Regional Comparisons of Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 171, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, T.; Iida, Y.; Nakanishi, H.; Terada, N.; Morooka, S.; Yamada, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Yokota, S.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshimura, N. Microvascular Density in Glaucomatous Eyes With Hemifield Visual Field Defects: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 168, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.L.; Zhang, A.; Bojikian, K.D.; Wen, J.C.; Zhang, Q.; Xin, C.; Mudumbai, R.C.; Johnstone, M.A.; Chen, P.P.; Wang, R.K. Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Vascular Microcirculation in Glaucoma Using Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Microangiography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, OCT475–OCT485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, N.B.; Sullivan-Mee, M.; Harwerth, R.S. The relationship between retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and optic nerve head neuroretinal rim tissue in glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 6802–6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suh, M.H.; Zangwill, L.M.; Manalastas, P.I.; Belghith, A.; Yarmohammadi, A.; Medeiros, F.A.; Diniz-Filho, A.; Saunders, L.J.; Yousefi, S.; Weinreb, R.N. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density in Glaucomatous Eyes with Focal Lamina Cribrosa Defects. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Javed, A.; Khanna, A.; Palmer, E.; Wilde, C.; Zaman, A.; Orr, G.; Kumudhan, D.; Lakshmanan, A.; Panos, G.D. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography: A Review of the Current Literature. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231187933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triolo, G.; Rabiolo, A. Optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography in glaucoma: Diagnosis, progression, and correlation with functional tests. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 12, 2515841419899822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, L.; Jia, Y.; Takusagawa, H.L.; Pechauer, A.D.; Edmunds, B.; Lombardi, L.; Davis, E.; Morrison, J.C.; Huang, D. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography of the Peripapillary Retina in Glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bekkers, A.; Borren, N.; Ederveen, V.; Fokkinga, E.; Andrade De Jesus, D.; Sánchez Brea, L.; Klein, S.; van Walsum, T.; Barbosa-Breda, J.; Stalmans, I. Microvascular damage assessed by optical coherence tomography angiography for glaucoma diagnosis: A systematic review of the most discriminative regions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, 537–558, Erratum in Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, 572. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14481. PMID: 32180360; PMCID: PMC7497179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.K.; Kim, J.H.; Toh, G.; Na, K.I.; Seong, M.; Lee, W.J. Diagnostic performance of wide-field optical coherence tomography angiography for high myopic glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, H.L.; Hong, K.E.; Shin, D.Y.; Jung, Y.; Kim, E.K.; Park, C.K. Microvasculature Recovery Detected Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and the Rate of Visual Field Progression After Glaucoma Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 17, Erratum in Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 42. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.63.1.42. PMID: 34932063; PMCID: PMC8709933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormel, T.T.; Huang, D.; Jia, Y. Advances in OCT Angiography. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Li, F.; Gao, K.; He, W.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Cheng, W.; Song, Y.; Peng, Y.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in Macular Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Metrics in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma with High Myopia: A Prospective Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miguel, A.; Silva, A.; Barbosa-Breda, J.; Azevedo, L.; Abdulrahman, A.; Hereth, E.; Abegão Pinto, L.; Lachkar, Y.; Stalmans, I. OCT-angiography detects longitudinal microvascular changes in glaucoma: A systematic review. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento ESilva, R.; Chiou, C.A.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Shoji, M.K.; Chou, J.C.; D’Souza, E.E.; Greenstein, S.H.; Brauner, S.C.; Alves, M.R.; et al. Microvasculature of the Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Region in Patients with Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2019, 28, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mursch-Edlmayr, A.S.; Bolz, M.; Strohmaier, C. Vascular Aspects in Glaucoma: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akil, H.; Huang, A.S.; Francis, B.A.; Sadda, S.R.; Chopra, V. Retinal vessel density from optical coherence tomography angiography to differentiate early glaucoma, pre-perimetric glaucoma and normal eyes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lei, J.; Durbin, M.K.; Shi, Y.; Uji, A.; Balasubramanian, S.; Baghdasaryan, E.; Al-Sheikh, M.; Sadda, S.R. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Superficial Macular Retinal Vessel Density Measurements Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography En Face Images. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suh, M.H.; Jung, D.H.; Weinreb, R.N.; Zangwill, L.M. Optic Disc Microvasculature Dropout in Glaucoma Detected by Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 236, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Glaucoma (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | Between-Group Diff (G−C) | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.77 ± 3.94 | 64.87 ± 5.64 | 0.90 | −1.62 to 3.42 | 0.18 | 0.477 |

| RNFL mean (baseline, µm) | 85.90 ± 10.03 | 98.02 ± 6.11 | −12.12 | −16.43 to −7.81 | −1.46 | 8.54 × 10−7 |

| MD (baseline, dB) | −2.82 ± 0.48 | 0.64 ± 0.85 | −3.45 | −3.81 to −3.10 | −5.01 | 8.91 × 10−24 |

| IOP (baseline, mmHg) | 19.28 ± 1.16 | 16.48 ± 1.68 | 2.80 | 2.06 to 3.55 | 1.94 | 7.45 × 10−10 |

| PP-VD (%) | 45.33 ± 2.74 | 51.64 ± 1.85 | −6.31 | −7.52 to −5.10 | −2.69 | 3.02 × 10−14 |

| PF-VD (%) | 44.58 ± 2.84 | 51.25 ± 1.62 | −6.67 | −7.87 to −5.47 | −2.89 | 9.93 × 10−15 |

| RPC VD whole image (%) | 43.69 ± 2.66 | 50.27 ± 1.71 | −6.57 | −7.73 to −5.41 | −2.93 | 2.13 × 10−15 |

| Variable | Glaucoma (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | Δ Difference (G–C) | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ RNFL mean (µm) | −1.04 ± 0.40 | −0.22 ± 1.16 | −0.82 | −1.28 to −0.36 | −0.94 | 0.000828 |

| Δ MD (dB) | −0.10 ± 0.24 | +0.06 ± 0.14 | −0.16 | −0.26 to −0.06 | −0.81 | 0.00281 |

| Δ IOP (mmHg) | −0.21 ± 1.40 | +0.42 ± 0.81 | −0.63 | −1.22 to −0.04 | −0.55 | 0.0379 |

| Δ PP-VD (%) | −0.57 ± 0.56 | +0.02 ± 0.21 | −0.59 | −0.81 to −0.37 | −1.41 | 3.37 × 10−6 |

| Δ PF-VD (%) | −0.15 ± 0.59 | −0.54 ± 1.49 | +0.39 | −0.20 to 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.187 |

| Δ RPC whole-image VD (%) | −0.35 ± 0.58 | +0.00 ± 0.42 | −0.35 | −0.62 to −0.09 | −0.69 | 0.00997 |

| Outcome | Group Effect B (G vs. C) | 95% CI for B | F (1,55) | p-Value | Partial η2 | Model R2 | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNFL mean (6 months, µm) | −0.56 | −1.13 to 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.0505 | 0.068 | 0.994 | 0.993 |

| MD (6 months, dB) | −0.20 | −0.48 to 0.08 | 2.05 | 0.157 | 0.036 | 0.991 | 0.990 |

| IOP (6 months, mmHg) | +0.43 | −0.35 to 1.20 | 1.23 | 0.272 | 0.022 | 0.679 | 0.656 |

| PP-VD (6 months, %) | −1.22 | −1.53 to −0.90 | 58.64 | <0.001 | 0.516 | 0.993 | 0.992 |

| PF-VD (6 months, %) | −0.59 | −1.62 to 0.44 | 1.30 | 0.258 | 0.023 | 0.924 | 0.918 |

| RPC whole-image VD (6 months, %) | +0.11 | −0.33 to 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.610 | 0.005 | 0.989 | 0.988 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kancheva, K.; Radeva, M.; Resnick, I.B.; Zlatarova, Z. Evaluation of OCT Angiography Parameters as Biomarkers for Glaucoma Progression. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010035

Kancheva K, Radeva M, Resnick IB, Zlatarova Z. Evaluation of OCT Angiography Parameters as Biomarkers for Glaucoma Progression. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleKancheva, Konstantina, Mladena Radeva, Igor B. Resnick, and Zornitsa Zlatarova. 2026. "Evaluation of OCT Angiography Parameters as Biomarkers for Glaucoma Progression" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010035

APA StyleKancheva, K., Radeva, M., Resnick, I. B., & Zlatarova, Z. (2026). Evaluation of OCT Angiography Parameters as Biomarkers for Glaucoma Progression. Diagnostics, 16(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010035