Macular Microvasculature Is Different in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Disease Compared to Healthy Controls

Abstract

1. Introduction

- SjD is characterized by mononuclear cell infiltration of the exocrine glands, particularly the lacrimal glands. This lymphoid infiltration leads to ocular dryness, also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Anterior segment ocular manifestations, such as dry eye, are common in SjD and can have a significant impact on the patients’ quality of life [7]. However, it remains unclear whether or not SjD also affects the retinal microvasculature. Understanding the impact of SjD on the retinal vasculature is important for several reasons. First, changes in the retinal vascular structure may be indicative of inflammatory events in the retinal vasculature in SjD [5,8,9]. A recent review by Hysa et al. [10] highlights how autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) contribute to ocular microvascular damage through mechanisms such as immune complex formation, complement activation, and antibody-mediated injury to the endothelium. This resulting endothelial dysfunction in the ocular vessels mirrors a broader systemic vascular involvement, suggesting that retinal microvascular alterations may serve as early indicators of widespread vascular damage [10]. Second, these alterations may be linked with other aspects of vascular disease in SjD, such as Raynaud’s syndrome or vasculitis [11,12]. Assessment of the retinal vasculature by optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) could potentially predict microvasculature involvement and may help to understand pathophysiological processes in SjD.

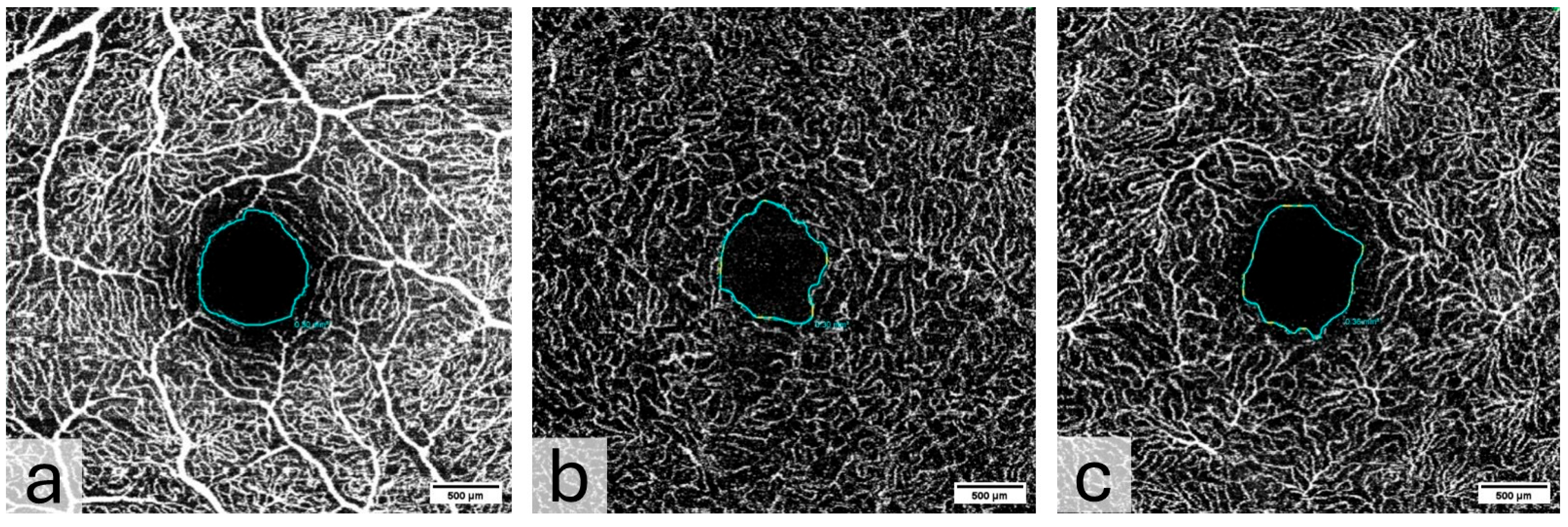

- The ocular microvasculature is unique in that it can be directly visualized, imaged, and quantified in a non-invasive manner using OCTA. OCTA detects retinal blood flow down to the capillary level by measuring changes in multiple cross-sectional images (B-frames) of the same area [13,14]. OCTA can be used to measure the size of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ) and the vessel area density (VAD) around the macula [15,16].

- The center of the fovea is called the FAZ. The FAZ is a specialized area of the human macula, nourished by the choroid, which contains the highest density of cone photoreceptors and has the greatest oxygen consumption [17]. The FAZ is highly sensitive to ischemia and may be an indicator of retinal vascular non-perfusion. When the retinal vessels are damaged, the choroid is unable to supply oxygen to the inner layers of the retina [18].

- The retinal microvasculature consists of capillary networks that surround and supply the fovea; the Superficial Vascular Plexus (SVP), the intermediate capillary plexus (ICP), and the Deep Capillary Plexus (DCP). However, these networks remain outside the central foveal avascular zone (FAZ) [19]. The SVP is supplied by the central retinal artery and composed of larger arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins primarily in the ganglion cell layer. There are two deeper capillary networks above and below the inner nuclear layer known as the “intermediate” and “deep” capillary plexuses, or ICP and DCP, respectively, which are supplied by vertical anastomoses from the SVP [14]. Changes in capillary density and FAZ size or morphology may reflect changes in retinal perfusion and vascular integrity [20,21].

2. Materials and Methods

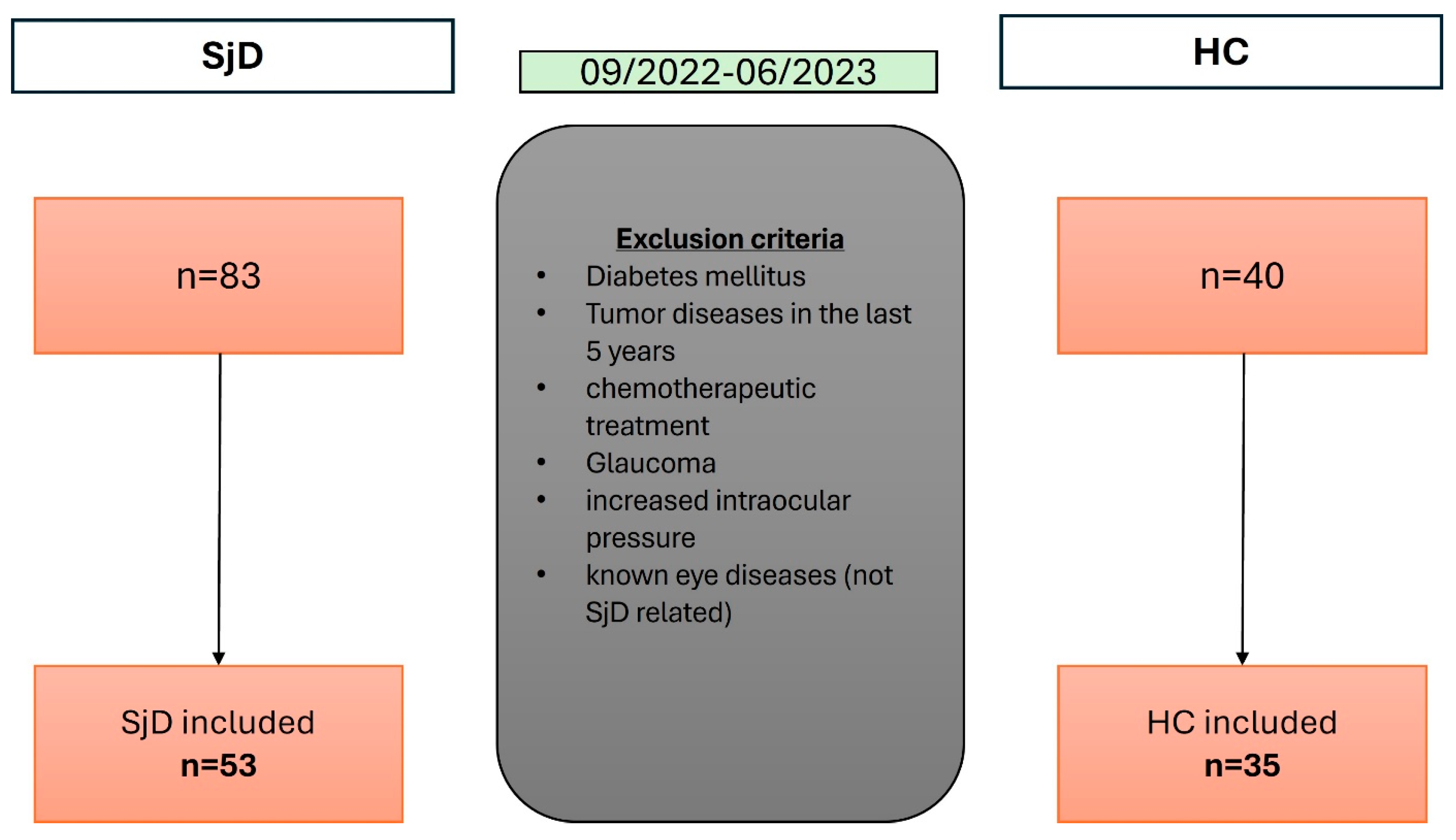

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Initial Questionnaire, Clinical Examination, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.5. Methodology of the Ophthalmological Examination

2.6. Measurement of the Axial Length

2.7. Slit Lamp Examination

2.8. Tear Secretion Tests

2.9. Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography and Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography

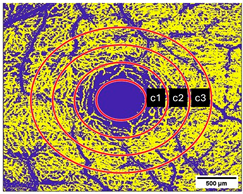

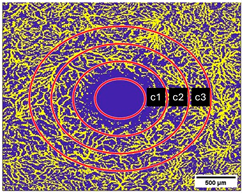

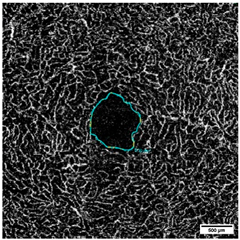

2.10. Measurement of the Vessel Area Density (VAD, %) and the FAZ (mm2)

2.11. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics Results

3.2. Initial Questionnaire, Clinical Findings, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

3.3. Ophthalmological Examination

3.4. Vessel Area Density (VAD, %)

3.5. Foveal Avascular Zone (FAZ, mm2)

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between FAZ and VAD

3.7. Correlation Analysis Between VAD/FAZ and SjD Disease Duration (DD)

3.8. Comparison Between the Active HCQ Group and the Prior/No HCQ Group and VAD/FAZ

3.9. Point–Biserial Correlation of the Relationship Between HCQ Treatment Status and VAD/FAZ

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR/EULAR | American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism |

| BCVA | best corrected visual acuity |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BUT | tear break-up time |

| CRP | C reactive protein |

| DD | disease duration |

| DDM | disease duration month |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| EAT | Erlangen Angio Tool |

| ESSDAI | EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome disease activity index |

| ESSPRI | EULAR Sjogren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index |

| FAZ | foveal avascular zone |

| HCs | healthy controls |

| HCQ | hydroxychloroquine |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| IOP | intraocular pressure |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LIPCOF | lid-parallel conjunctival folds |

| LPA | lipoprotein a |

| OCTA | optical coherence tomography angiography |

| OD | oculus dexter |

| OS | oculus sinister |

| OSDI | Ocular Surface Disease Index |

| SD-OCT | spectral domain optical coherence tomography |

| SjD | Sjögren’s disease |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematode |

| SSA/Ro-AB | anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A antibodies |

| SSB/La-AB | anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen B antibodies |

| VAD | vessel area density |

References

- Westhoff, G.; Zink, A. Epidemiology of Primary Sjörgren’s Syndrome. Z. Rheumatol. 2010, 69, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, S.J.; Ibrahim, G.H.; Holmes, G.; Hamburger, J.; Ainsworth, J.R. Estimating the Prevalence among Caucasian Women of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome in Two General Practices in Birmingham, UK. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 33, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birlik, M.; Akar, S.; Gurler, O.; Sari, I.; Birlik, B.; Sarioglu, S.; Oktem, M.A.; Saglam, F.; Can, G.; Kayahan, H.; et al. Prevalence of Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome in Turkey: A Population-Based Epidemiological Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zippel, C.L.; Beider, S.; Kramer, E.; Konen, F.F.; Seeliger, T.; Skripuletz, T.; Hirsch, S.; Jablonka, A.; Witte, T.; Sonnenschein, K.; et al. Premature Stroke and Cardiovascular Risk in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1048684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrfeld, N.; Abelmann, M.; Benz, S.; Zippel, C.L.; Beider, S.; Kramer, E.; Seeliger, T.; Sogkas, G.; Gödecke, V.; Ahrenstorf, G.; et al. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Independently Promotes Premature Subclinical Atherosclerosis. RMD Open 2024, 10, e003559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, T.; Kramer, E.; Konen, F.F.; Zehrfeld, N.; Beider, S.; Prenzler, N.K.; Gödecke, V.; Witte, T.; Skripuletz, T.; Ernst, D. Sjögren’s Syndrome with and without Neurological Involvement. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2987–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauqeer, Z.; Bunya, V.Y.; Macchi, I.; Massaro-Giordano, M. Ocular Pathophysiology of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 29, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, J. Critical Roles of Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. J. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, B.; Zang, A.-L.; Stingl, J.; Hasseli-Fräbel, R.; Fanouriakis, A.; Schwarting, A.; Geber, C.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; Alhaddad, M.; Triantafyllias, K. Ocular Markers of Microangiopathy and Their Possible Association with Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Systemic Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1543157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, E.; Cutolo, C.A.; Gotelli, E.; Paolino, S.; Cimmino, M.A.; Pacini, G.; Pizzorni, C.; Sulli, A.; Smith, V.; Cutolo, M. Ocular Microvascular Damage in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases: The Pathophysiological Role of the Immune System. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdovinos, S.T.; Landry, G.J. Raynaud Syndrome. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2014, 17, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodakçi, E. Clinical Characteristics of Distinct Subgroups of Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Classified by Serological Profiles: A Comparison Study. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaide, R.F.; Klancnik, J.M.; Cooney, M.J. Retinal Vascular Layers Imaged by Fluorescein Angiography and Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.P.; Zhang, M.; Hwang, T.S.; Bailey, S.T.; Wilson, D.J.; Jia, Y.; Huang, D. Detailed Vascular Anatomy of the Human Retina by Projection-Resolved Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindziute, M.; Kaufeld, J.; Hufendiek, K.; Volkmann, I.; Brockmann, D.; Hosari, S.; Hohberger, B.; Christian, M.; Framme, C.; Jan, T.; et al. Correlation of Retinal Vascular Characteristics with Laboratory and Ocular Findings in Fabry Disease: Exploring Ocular Diagnostic Biomarkers. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufendiek, K.; Lindziute, M.; Kaufeld, J.; Volkmann, I.; Brockmann, D.; Hosari, S.; Hohberger, B.; Mardin, C.; Framme, C.; Tode, J.; et al. Investigation of OCTA Biomarkers in Fabry Disease: A Long Term Follow-Up of Macular Vessel Area Density and Foveal Avascular Zone Metrics. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 2713–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.B.; Schneider, U.; Naumann, G.O. Count and Density of Human Retinal Photoreceptors. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1992, 230, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.-Y.; Cringle, S.J.; Yu, P.K.; Su, E.-N. Intraretinal Oxygen Distribution and Consumption during Retinal Artery Occlusion and Graded Hyperoxic Ventilation in the Rat. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, W.A.; Say, E.A.T.; Khoo, C.T.L.; Higgins, T.P.; Magrath, G.; Ferenczy, S.; Shields, C.L. CORRELATION OF FOVEAL AVASCULAR ZONE SIZE WITH FOVEAL MORPHOLOGY IN NORMAL EYES USING OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY. Retina 2015, 35, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, H.; Sun, X. Factors Affecting the Foveal Avascular Zone Area in Healthy Eyes among Young Chinese Adults. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7361492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, G.; O’Shea, S.; Amarandei, G.; Butler, J.S.; O’Dwyer, V. Investigation of Factors That May Affect the Foveal Avascular Zone: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2024, 101, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seror, R.; Bowman, S.J.; Brito-Zeron, P.; Theander, E.; Bootsma, H.; Tzioufas, A.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; Ramos-Casals, M.; Dörner, T.; Ravaud, P.; et al. EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI): A User Guide. RMD Open 2015, 1, e000022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, R.M. Reliability and Validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemp, M.A.; Foulks, G.N. The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocul. Surf. 2007, 5, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Patel, P. Calculated Decisions: Visual Acuity Testing (Snellen Chart). Emerg. Med. Pract. 2020, 22, CD1–CD2. [Google Scholar]

- Serruya, L.G.; Nogueira, D.C.; Hida, R.Y. Schirmer Test Performed with Open and Closed Eyes: Variations in Normal Individuals. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2009, 72, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H. Biostatistics 104: Correlational Analysis. Singapore Med. J. 2003, 44, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.-C.; Yao, F.; Li, Q.-Y.; Chen, M.-J.; Zhang, L.-J.; Shu, H.-Y.; Liang, R.-B.; Pan, Y.-C.; Ge, Q.-M.; Shao, Y. Ocular Microvascular Alteration in Sjögren Syndrome. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, N.P.; Ayar, K. Evaluation of Retinal Microvascular Structures by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zou, J.; Ge, Q.-M.; Liao, X.-L.; Pan, Y.-C.; Wu, J.-L.; Su, T.; Zhang, L.-J.; Liang, R.-B.; Shao, Y. Ocular Microvascular Alteration in Sjögren’s Syndrome Treated with Hydroxychloroquine: An OCTA Clinical Study. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2023, 14, 20406223231164498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, E.; Wicklein, R.; Aly, L.; Schmaderer, C.; Afzali, A.M.; Mardin, C.; Korn, T.; Hemmer, B.; Hofauer, B.; Knier, B. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Suggests Different Retinal Pathologies in Multiple Sclerosis and Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 4610–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Q.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Liao, R.; Shuai, Z. Analysis of Foveal Microvascular Abnormalities in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 29, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaratnasingam, C.; Inoue, M.; Ahn, S.; McCann, J.; Dhrami-Gavazi, E.; Yannuzzi, L.A.; Freund, K.B. Visual Acuity Is Correlated with the Area of the Foveal Avascular Zone in Diabetic Retinopathy and Retinal Vein Occlusion. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2352–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Xie, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, H. Characterization of the Retinal Microvasculature and FAZ Changes in Ischemic Stroke and Its Different Types. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M.; Elkhalifa, M.; Li, J.; Magder, L.S.; Goldman, D.W. Hydroxychloroquine Blood Levels Predict Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmor, M.F. Comparison of Screening Procedures in Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2012, 130, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozek, D.; Onen, M.; Karaca, E.E.; Omma, A.; Kemer, O.E.; Coskun, C. The Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Taking Hydroxychloroquine. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 29, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilijević, J.B.; Kovačević, I.M.; Dijana, R.; Dačić, B.; Marić, G.; Stanojlović, S. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Parameters in Patients Taking Hydroxychloroquine Therapy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 3399–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.S.; Woodham, M.; Bartels, C.M.; Saldanha, I.J.; Bunya, V.Y.; Maerz, N.; Akpek, E.K.; Makara, M.A.; Baer, A.N. Symptom-Based Cluster Analysis Categorizes Sjögren’s Disease Subtypes: An International Cohort Study Highlighting Disease Severity and Treatment Discordance. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltai, A.; Barnetche, T.; Daien, C.; Lukas, C.; Gaujoux-Viala, C.; Combe, B.; Morel, J. Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sjögren Disease N = 53 | Healthy Controls N = 35 | |

|---|---|---|

| General data | ||

| Mean age [years] | 54.3 | 55.1 |

| Female [%] | 77 | 76 |

| First diagnosed SjD [mth.] | 98.8 ± 86 | |

| First manifestation SjD [mth.] | 150.9 ± 97.8 | |

| Indexes and Tests | ||

| ESSPRI [0–30] | 6.1 ± 4.4 | 0 |

| ESSDAI-mean | 14.1 ± 1.4 | 0 |

| ESSDAI [hematological domain] | 1 ± 0.2 | 0 |

| OSDI [0–48] | 10.1 ± 9.1 | 0 |

| Path. Schirmer I * | 23/53 (43.4%) | 1/35 (2.9%) |

| Path. Schirmer II ** | 26/53 (49.1%) | 1/35 (2.9%) |

| Path. Salivary gland biopsy | 44/53 (83.0%) | |

| Clinical and Cardiovascular risk factors | ||

| SSA/Anti-Ro Antibody pos. | 24/53 (45.3%) | 0 |

| SSB/Anti-La Antibody pos. | 5/53 (9.4%) | 0 |

| ANA Antibody pos. | 33/53 (63.2%) | 0 |

| HbA1c [%] | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.4 |

| Cholesterol [mmol/L] | 5.± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.2 |

| HDL-Cholesterol [mmol/L] | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| LDL-Cholesterol [mmol/L] | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

| Triglyceride [mmol/L] | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 1.0 |

| Lipoprotein A [mmol/L] | 65.9 ± 58.8 | 38.8 ± 49 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 19/53 | 0/35 |

| Art. hypertension | 16/53 (30%) | 8/35 (23%) |

| Previous thrombotic events | 8/53 | 1/35 |

| Cutaneous vasculitis | 2/53 | 0/35 |

| CRP [mg/dL] | 3.0 ± 3.9 | 2.1 ± 2.2 |

| BMI | 24.3 ± 5.0 | 24.3 ± 5.1 |

| Xerostomy [%] | 64 (34/53) | 0 (0/35) |

| HCQ therapy | ||

| HCQ | N = 42 | |

| HCQ act. | N = 26 | |

| HCQ duration [mth] | 46 | |

| Results in Microvasculature | SjD Cohort | HC Cohort | p Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVP | VAD c1 [%] | 44.6 ± 10.2 | 47.0 ± 10.9 | 0.136 |

| VAD c2 [%] | 53.5 ± 10.4 | 54.0 ± 10.3 | 0.769 | ||

| VAD c3 [%] | 47.2 ± 10.1 | 47.1 ± 10.8 | 0.955 | ||

| VADc1 + c2 + c3 [%] | 145.3 ± 28.5 | 148.4 ± 29.7 | 0.496 | ||

| ICP | VAD c1 [%] | 25.8 ± 5.6 | 26.5 ± 4.7 | 0.379 |

| VAD c2 [%] | 27.4 ± 6.5 | 27.7 ± 4.8 | 0.717 | ||

| VAD c3 [%] | 26.0 ± 6.8 | 26.4 ± 5.3 | 0.636 | ||

| VADc1 + c2 + c3 [%] | 79.1 ± 18.2 | 80.8 ± 14.1 | 0.517 | ||

| DCP | VAD c1 [%] | 29.1 ± 7.1 | 31.8 ± 9.6 | 0.038 |

| VAD c2 [%] | 34.1 ± 7.5 | 36.3 ± 7.9 | 0.072 | ||

| VAD c3 [%] | 32.7 ± 8.1 | 34.4 ± 7.8 | 0.180 | ||

| VAD c1 + c2 + c3 [%] | 96.0 ± 21.7 | 102.4 ± 23.8 | 0.667 | ||

| FAZ SVP | SVP [mm2] | 0.41 ± 0.13 | 0.34 ± 0.33 | <0.001, Cohen’s d 0.55 |

| FAZ ICP | ICP [mm2] | 0.24 ± 0.10 | 0.2 ± 0.10 | 0.082 |

| FAZ DCP | DCP [mm2] | 0.45 ± 0.15 | 0.4 ± 0.14 | 0.014, Cohen’s d 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tadsen, G.; Zehrfeld, N.; Hoffmann, L.; Gehlhaar, M.; Hohberger, B.; Mardin, C.; Witte, T.; Framme, C.; Ernst, D.; Hufendiek, K. Macular Microvasculature Is Different in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Disease Compared to Healthy Controls. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131701

Tadsen G, Zehrfeld N, Hoffmann L, Gehlhaar M, Hohberger B, Mardin C, Witte T, Framme C, Ernst D, Hufendiek K. Macular Microvasculature Is Different in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Disease Compared to Healthy Controls. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(13):1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131701

Chicago/Turabian StyleTadsen, Gyde, Nadine Zehrfeld, Laura Hoffmann, Marten Gehlhaar, Bettina Hohberger, Christian Mardin, Torsten Witte, Carsten Framme, Diana Ernst, and Katerina Hufendiek. 2025. "Macular Microvasculature Is Different in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Disease Compared to Healthy Controls" Diagnostics 15, no. 13: 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131701

APA StyleTadsen, G., Zehrfeld, N., Hoffmann, L., Gehlhaar, M., Hohberger, B., Mardin, C., Witte, T., Framme, C., Ernst, D., & Hufendiek, K. (2025). Macular Microvasculature Is Different in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Disease Compared to Healthy Controls. Diagnostics, 15(13), 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131701