Live-Cell-Based Assay Outperforms Fixed Assay in MOGAD Diagnosis: A Retrospective Validation Against the 2023 International Criteria

Abstract

1. Introduction

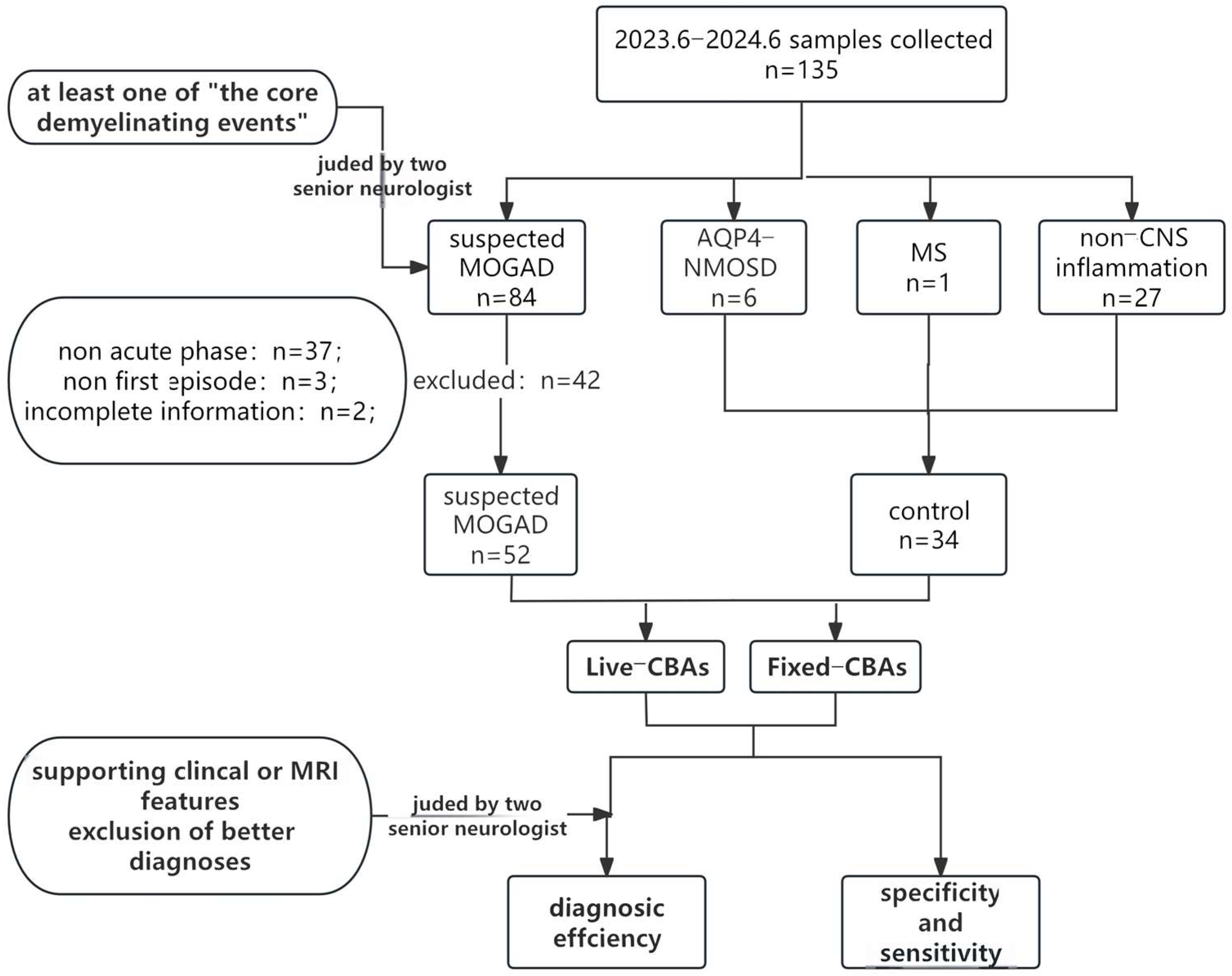

2. Methods

2.1. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

2.2. Study Population and Controls

- (1)

- participants must exhibit at least one of the core demyelination events outlined in the MOGAD criteria 2023 [6];

- (2)

- participants must also not meet the diagnostic criteria for other central nervous system demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) with aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4-Abs) positivity.

- (1)

- serum samples obtained outside the acute disease stage (i.e., beyond one month after onset);

- (2)

- incomplete data.

2.3. MOG-IgG Assays

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruijstens, A.L.; Wendel, E.M.; Lechner, C.; Bartels, F.; Finke, C.; Breu, M.; Flet-Berliac, L.; de Chalus, A.; Adamsbaum, C.; Capobianco, M.; et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 5 e Treatment of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2020, 29, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Chiriboga, A.S.; Majed, M.; Fryer, J.; Dubey, D.; McKeon, A.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Kothapalli, N.; Tillema, J.M.; Chen, J.; et al. Association of MOG-IgG Serostatus With Relapse After Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis and Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for MOG-IgG-Associated Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionatti, A.; Hansel, G.; Avila, G.U.; Sato, D.K. Detection of MOG-IgG in Clinical Samples by Live Cell-Based Assays: Performance of Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Flow Cytometry. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 642272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcadela, M.; Rocchi, C.; Martin, D.S.; Gibbons, E.L.; Wells, D.; Woodhall, M.R.; Waters, P.J.; Huda, S.; Hamid, S. Timing of MOG-IgG Testing is Key to 2023 MOGAD Diagnostic Criteria. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 11, e200183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaboudi, M.; Morgan, M.; Serra, A.; Abboud, H. Utility of the 2023 international MOGAD panelproposed criteria in clinical practice: An institutional cohort. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 81, 105150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Marignier, R.; Kim, H.J.; Brilot, F.; Flanagan, E.P.; Ramanathan, S.; Waters, P.; Tenembaum, S.; Graves, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, P.J.; Komorowski, L.; Woodhall, M.; Lederer, S.; Majed, M.; Fryer, J.; Mills, J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Irani, S.R.; Kunchok, A.C.; et al. A multicenter comparison of MOG-IgG cell-based assays. Neurology 2019, 92, e1250–e1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Singh, S.; Feltrin, F.S.; Tardo, L.M.; Clarke, R.L.; Wang, C.X.; Greenberg, B.M. The positive predictive value of MOG-IgG testing based on the 2023 diagnostic criteria for MOGAD. Mult. Scler. J.-Exp. Transl. Clin. 2024, 10, 1184329486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhram, A.; Flanagan, E.P. Testing for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: Who, what, where, when, why, and how. Mult. Scler. 2025, 31, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, M.; Schanda, K.; Woodhall, M.; Tea, F.; Ramanathan, S.; Sagen, J.; Fryer, J.P.; Mills, J.; Teegen, B.; Mindorf, S.; et al. International multicenter examination of MOG antibody assays. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, M.; Scaranzin, S.; Jarius, S.; Wildeman, B.; Zardini, E.; Mallucci, G.; Rigoni, E.; Vegezzi, E.; Foiadelli, T.; Savasta, S.; et al. Cell-based assays for the detection of MOG antibodies: A comparative study. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 3555–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippatou, A.G.; Said, Y.; Chen, H.; Vasileiou, E.S.; Ahmadi, G.; Sotirchos, E.S. Validation of the international MOGAD panel proposed criteria: A single-centre US study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graus, F.D.J. MOGAD comes of age with new criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 193–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, J.Y.; Fujihara, K. Epidemiology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: A review of prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1260358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, L.; DCunha, A.; Malli, C.; Sudhir, A. Comparison of live and fixed cell-based assay performance: Implications for the diagnosis of MOGAD in a low-middle income country. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1252650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, S.; Cobo Calvo, Á.; Armangué, T.; Saiz, A.; Lechner, C.; Rostásy, K.; Breu, M.; Baumann, M.; Höftberger, R.; Ayzenberg, I.; et al. Significance of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies in CSF: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Neurology 2023, 100, e1095–e1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kaneko, K.; Takahashi, T.; Takai, Y.; Namatame, C.; Kuroda, H.; Misu, T.; Fujihara, K.; Aoki, M. Diagnostic implications of MOG-IgG detection in sera and cerebrospinal fluids. Brain A J. Neurol. 2023, 146, 3938–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhou, A.; Zhou, J.; Zhuo, X.; Dai, L.; Tian, X.; Yang, X.; Gong, S.; Ding, C.; Fang, F.; et al. Encephalitis is an Important Phenotype of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Diseases: A Single-Center Cohort Study. Pediatr. Neurol. 2024, 152, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombolay, G.Y.; Gadde, J.A. Aseptic meningitis and leptomeningeal enhancement associated with anti-MOG antibodies: A review. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 358, 577653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udani, V.; Badheka, R.; Desai, N. Prolonged Fever: An Atypical Presentation in MOG Antibody-Associated Disorders. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciaguerra, L.; Morris, P.; Tobin, W.O.; Chen, J.J.; Banks, S.A.; Elsbernd, P.; Redenbaugh, V.; Tillema, J.-M.; Montini, F.; Sechi, E.; et al. Tumefactive Demyelination in MOG Ab-Associated Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and AQP-4-IgG-Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Neurology 2023, 100, e1418–e1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changhong, R.; Ming, L.; Anna, Z.; Ji, Z.; Xiuwei, Z.; Xiaojuan, T.; Xinying, Y.; Shuai, G.; Fang, F.; Xiaotun, R.; et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated meningoencephalitis without cerebral parenchyma involvement on MRI: A single-centre paediatric cohort study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marignier, R.; Hacohen, Y.; Cobo-Calvo, A.; Pröbstel, A.K.; Aktas, O.; Alexopoulos, H.; Amato, M.P.; Asgari, N.; Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.; et al. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, A.; Chen, J.J.; Costello, F. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD): Current understanding and challenges. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 4132–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechi, E.; Cacciaguerra, L.; Chen, J.J.; Mariotto, S.; Fadda, G.; Dinoto, A.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Pittock, S.J.; Flanagan, E.P. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD): A Review of Clinical and MRI Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 885218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümpfel, T.; Giglhuber, K.; Aktas, O.; Ayzenberg, I.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Häußler, V.; Havla, J.; Hellwig, K.; Hümmert, M.W.; Jarius, S.; et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD)—Revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Part II: Attack therapy and long-term management. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 141–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, B.; Sahraian, M.; Bohlega, S.; Al-Jumah, M.; Goueider, R.; Dahdaleh, M.; Inshasi, J.; Hashem, S.; Alsharoqi, I.; Khoury, S.; et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: 2019 revisions to the MENACTRIMS guidelines. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 37, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzolato Umeton, R.; Waltz, M.; Aaen, G.S.; Benson, L.; Gorman, M.; Goyal, M.; Graves, J.S.; Harris, Y.; Krupp, L.; Lotze, T.E.; et al. Therapeutic Response in Pediatric Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Neurology 2023, 100, e985–e994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trewin, B.P.; Dale, R.C.; Qiu, J.; Chu, M.; Jeyakumar, N.; Cruz, F.D.; Andersen, J.; Siriratnam, P.; Ma, K.K.M.; Hardy, T.A.; et al. Oral corticosteroid dosage and taper duration at onset in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease influences time to first relapse. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhram, A.; Dubey, D.; Sechi, E.; Flanagan, E.P.; Yang, L.; Bhayana, V.; McKeon, A.; Pittock, S.J.; Mills, J.R. Neural Antibody Testing in Patients with Suspected Autoimmune Encephalitis. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 1496–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fix–CBA | 44.2% | 97.1% | 95.8% | 53.2% |

| Live–CBA | 55.8% | 97.1% | 96.7% | 58.9% |

| Patient No. | Age (y) | Core Demyelination Events | MOG-Abs Test | Supporting Clinical or MRI Features | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON | ML | ADEM | BCD | CD | CCE | Fix-CBA | Live-CBA | |||

| 2 | 7.5 | + (left) | − | − | − | − | − | 1:10 | 1:320 | − |

| 3 | 7.9 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | 1:32 | + |

| 5 | 6.5 | + (right) | − | − | − | − | − | 1:10 | 1:100 | − |

| 27 | 6.8 | + (bilateral) | − | − | − | + | − | − | 1:100 | + |

| 29 | 11.5 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | 1:32 | + |

| 31 | 11.8 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | 1:10 | + |

| 46 | 10.5 | + (bilateral) | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1:10 | + |

| 48 | 9.1 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | 1:10 | + |

| 49 | 6.9 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | 1:32 | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, A.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Ren, C.; Zhan, K.; Li, W.; Xiong, H.; Ren, X. Live-Cell-Based Assay Outperforms Fixed Assay in MOGAD Diagnosis: A Retrospective Validation Against the 2023 International Criteria. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010157

Zhou A, Zhang W, Zhou J, Ren C, Zhan K, Li W, Xiong H, Ren X. Live-Cell-Based Assay Outperforms Fixed Assay in MOGAD Diagnosis: A Retrospective Validation Against the 2023 International Criteria. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Anna, Weihua Zhang, Ji Zhou, Changhong Ren, Ke Zhan, Wenhan Li, Hui Xiong, and Xiaotun Ren. 2026. "Live-Cell-Based Assay Outperforms Fixed Assay in MOGAD Diagnosis: A Retrospective Validation Against the 2023 International Criteria" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010157

APA StyleZhou, A., Zhang, W., Zhou, J., Ren, C., Zhan, K., Li, W., Xiong, H., & Ren, X. (2026). Live-Cell-Based Assay Outperforms Fixed Assay in MOGAD Diagnosis: A Retrospective Validation Against the 2023 International Criteria. Diagnostics, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010157