Ultrasound-Guided Dextrose Hydrodissection for Mixed Sensory–Motor Wartenberg’s Syndrome Following a Healed Scaphoid Fracture: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient Information

2.2. Clinical Findings and Timeline

- -

- Sensory Testing: Sensory impairment to light touch (using Semmes–Weinstein monofilament 2.83 g) and diminished two-point discrimination (>10 mm) specifically in the territory of the SBRN (first dorsal web space and radial border of the hand).

- -

- Motor Testing: Motor strength of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) was graded MRC 3/5, indicating anti-gravity strength with inability to overcome resistance. Strength in wrist dorsiflexion (extensor carpi radialis longus/brevis) and finger abduction (intrinsics) was normal (5/5).

- -

- Provocative Maneuvers: Tinel’s sign was markedly positive over the anatomical snuffbox, eliciting radiating paresthesias. Phalen’s test and Finkelstein’s test were negative, helping to rule out carpal tunnel syndrome and de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, respectively.

- -

- Pain Assessment: A Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for her dorsoradial wrist pain was 8/10 at rest, worsening with activity.

2.3. Diagnostic Assessment

- -

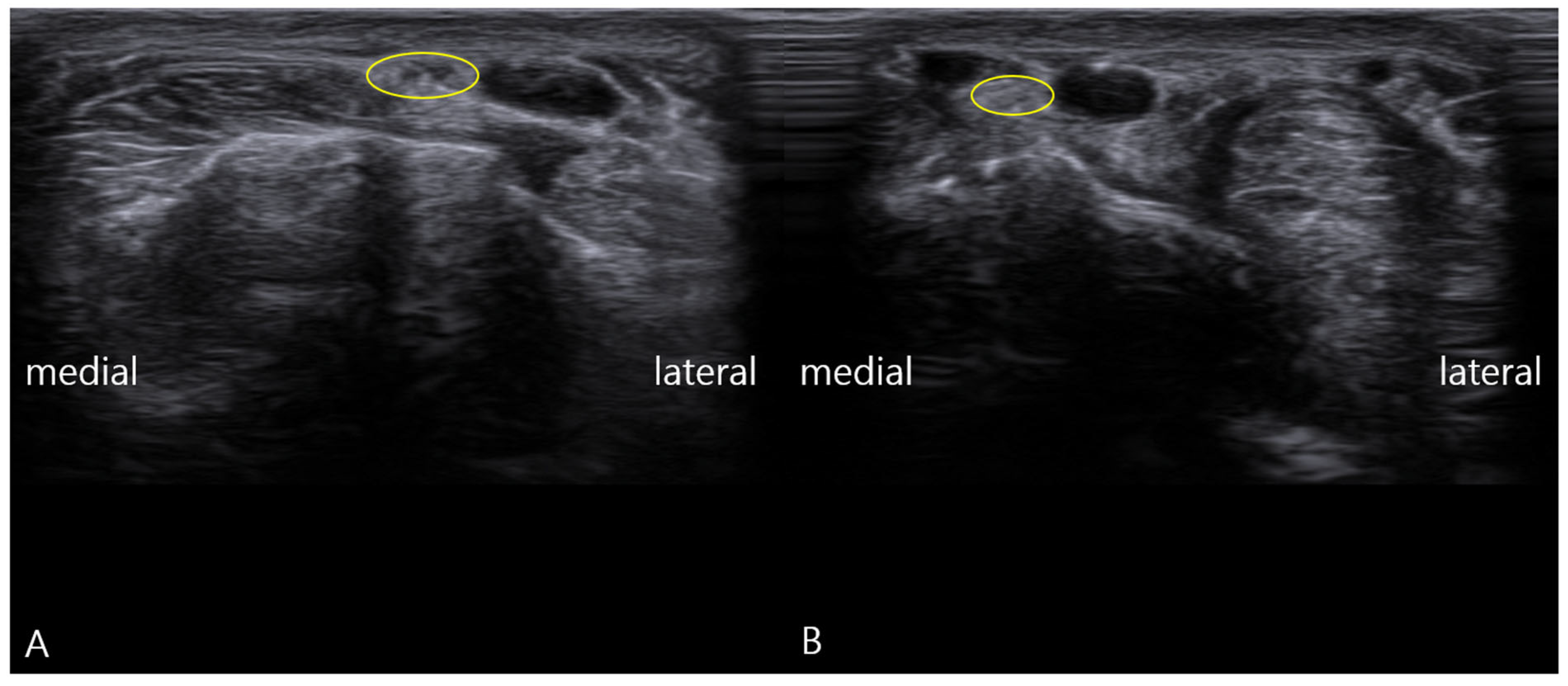

- Static Imaging: Transverse scans at the anatomical snuffbox revealed focal enlargement and loss of the normal fascicular echotexture of the SBRN on the symptomatic left side. The cross-sectional area (CSA) was measured at 0.13 cm2, significantly larger than the 0.08 cm2 on the asymptomatic right side (Figure 1). Power Doppler imaging showed mild hypervascularity around the left SBRN, suggesting ongoing inflammation.

- -

- Dynamic Imaging: The patient was positioned supine with her wrist in neutral. The examiner then applied a shearing force to the radial styloid process while imaging the SBRN. This maneuver demonstrated palpable, visible snapping of the SBRN over the bony prominence of the radial styloid during ulnar deviation of the wrist (Supplementary Video S1). This dynamic finding directly reproduced the patient’s characteristic pain, providing a direct link between the anatomy and her symptoms [26,27]. In addition, a hand grip-and-release maneuver provided comparative dynamic assessment, showing normal findings on the contralateral side (Supplementary Video S2) and abnormal motion-dependent findings on the symptomatic side (Supplementary Video S3).

2.4. Therapeutic Intervention

2.5. Follow-Up and Outcomes

- -

- Pain and Sensory Outcomes: The patient reported progressive pain relief. Her VAS score decreased from a baseline of 8/10 to 4/10 after the third session, to 1/10 after the seventh session, and ultimately to 0/10 upon completion of the ten-session series. The burning dysesthesia in the first web space resolved completely.

- -

- Motor Recovery: EPL strength improved steadily. It reached MRC grade 4/5 by the fifth session and normalized to full strength (5/5) by the eighth session.

- -

- Electrophysiological Confirmation: Follow-up NCS performed six weeks after the final treatment session confirmed the functional recovery, showing normalization of the EPL motor latency to 2.1 ms, with a stable CMAP amplitude of 3.5 mV (Table 1).

2.6. EPL: Extensor Pollicis Longus; CMAP: Compound Muscle Action Potential

- -

- Ultrasonographic Evidence: Post-treatment ultrasound revealed complete normalization of the SBRN’s appearance. The CSA decreased to 0.08 cm2, matching the asymptomatic side, and the fascicular echogenicity returned to normal. Most importantly, repeat dynamic assessment showed smooth, unimpeded gliding of the SBRN over the radial styloid without any snapping.

3. Discussion

3.1. Expanding the Clinical Phenotype of Wartenberg’s Syndrome

3.2. Pathophysiological Insights: The Role of Dynamic Snapping

3.3. The Critical Role of a Multimodal Diagnostic Approach

- -

- NCSs were essential for objectively confirming the functional impairment of the motor fibers (prolonged latency) and, surprisingly, ruling out significant sensory fiber dysfunction, which helped narrow the differential diagnosis. Notably, our findings are consistent with recent literature demonstrating that high-resolution ultrasound can reveal SBRN pathology even when electrodiagnostic studies are normal, as electrodiagnosis may miss focal nerve compression without significant axonal loss [25].

- -

- Static ultrasound identified the structural correlate of the neuropathy (nerve enlargement and hypoechogenicity), but was insufficient to explain the specific symptom mechanism.

- -

- Dynamic ultrasound provided the crucial kinematic link, directly visualizing the nerve snapping and reproducing the pain. It answered the “why” and “how” that the other tests could not [25]. In this context, dynamic ultrasound served as a vital problem-solving tool, uncovering the pathophysiological mechanism—nerve snapping—that was entirely invisible to conventional electrophysiology.

3.4. Hydrodissection and the Dual Mechanism of Dextrose

- Mechanical Neurolysis: The injected fluid creates a physical separation between the nerve and the surrounding constrictive tissues, lysing adhesions and effectively expanding the perineural space. This immediately alleviates mechanical compression and restores normal nerve gliding, as evidenced by the resolution of snapping on follow-up ultrasound.

- Neuromodulatory Effects of Dextrose: The use of 5% dextrose, rather than saline or local anesthetics, adds a therapeutic pharmacological dimension. Prolotherapy theories and emerging evidence suggest that dextrose acts as a mild irritant that may stimulate healing and have neuromodulatory properties. It is postulated to stabilize neuronal membranes, reduce ectopic discharges, and modulate pain receptors like TRPV1, thereby reducing neurogenic inflammation and pain signaling [31,32,33,34]. Randomized trials in carpal tunnel syndrome have shown superior outcomes with dextrose hydrodissection compared to saline, supporting its bioactive role [29].

3.5. Limitations and Future Directions

- -

- Larger prospective cohort studies to determine the true prevalence of motor involvement in Wartenberg’s syndrome.

- -

- Standardized protocols and diagnostic criteria for dynamic ultrasound assessment of peripheral nerves.

- -

- Long-term studies to evaluate the durability of hydrodissection effects.

- -

- Randomized controlled trials directly comparing dextrose hydrodissection with other established treatments, such as corticosteroid injection or surgical decompression, to establish evidence-based guidelines [29].

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tosun, N.; Tuncay, I.; Akpinar, F. Entrapment of the Sensory Branch of the Radial Nerve (Wartenberg’s Syndrome): An Unusual Cause. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2001, 193, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidwood, A.S. Superficial radial neuropathy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1975, 57, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, E.J.; Calfee, R.P. Uncommon upper extremity compression neuropathies. Hand Clin. 2013, 29, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.C.; Wendler, D.E.; Hrycko, E.R.; Puckett, H.D.; Lourie, G.M. Split Brachioradialis Tendon Causing Wartenberg Syndrome in a Professional Baseball Pitcher. J. Hand Surg. Glob. Online 2023, 5, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Jiang, H.; Dang, R.; Jiang, H.; Hu, X.; Hong, Z. An forearm anatomical study on muscular branches of radial nerve. J. Med. Postgrad. 2007, 20, 574–577. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas, M.; Louis, R.G.; Wartmann, C.T.; Tubbs, R.S.; Turan-Ozdemir, S.; Kramer, J. The clinical anatomy of the communications between the radial and ulnar nerves on the dorsal surface of the hand. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2008, 30, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serçe, A. An unexpected side effect: Wartenberg syndrome related to the use of splint during carpal tunnel syndrome treatment. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 64, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politylo, J.; A Decina, P.; A Lopes, A. Superficial radial neuropathy secondary to intravenous infusion at the wrist: A case report. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 1993, 37, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-G.; Son, B.-C. Cheiralgia paresthetica: An isolated neuropathy of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Nerve 2015, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, L.; Cooper, E.; Zhang, M.; Manheimer, E.; Berman, B.; Shen, X.; Lao, L. Adverse events of acupuncture: A systematic review of case reports. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 581203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Varacallo, M. Anatomy, shoulder and upper limb, hand extensor pollicis longus muscle. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.K.; Bun, H.R.; Hwang, M.; Hong, J.; Kim, D.H. Medial and lateral branches of the superficial radial nerve: Cadaver and nerve conduction studies. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, O.; Lomeli, B.A.; Andrakhanov, A.; Talisman, R. Combat-related Wartenberg Syndrome Due to Penetrating Shrapnel Injury: A Case Report. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Trikha, P.; Twyman, R. Superficial radial nerve damage due to Kirschner wiring of the radius. Injury 2005, 36, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.M.; Kuhl, T.L.; Adams, B.D. Early complications of volar plating of distal radius fractures and their relationship to surgeon experience. Hand 2011, 6, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.P.; Kane, P.M.; Shin, E.K. Management of complications of wrist arthroplasty and wrist fusion. Hand Clin. 2015, 31, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, T.K.; Berner, S.H.; Badia, A. New frontiers in hand arthroscopy. Hand Clin. 2011, 27, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyluk, A. Fractures of carpal bones other than scaphoid—A narrative review. Chir. Narządów Ruchu Ortop. Pol. 2024, 89, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.B.E.; Iyer, V.G.; Zhang, Y.P.; Shields, C.B. Etiological study of superficial radial nerve neuropathy: Series of 34 patients. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1175612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzetta, M.; Foucher, G. Entrapment of the superficial branch of the radial nerve (Wartenberg’s syndrome). A report of 52 cases. Int. Orthop. 1993, 17, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milch, E.; Epstein, M.D. Traumatic Rupture of the Extensor Pollicis Longus Tendon. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1987, 19, 460–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdes, H.; Ozdemir, E.; Kose, H.; Ertem, K. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy due to lipoma: A rare case report. Med. Sci. 2023, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AANEM Professional Practice Committee. Establishing Standards for Acceptable Waveforms in Nerve Conduction Studies. Muscle Nerve 2020, 62, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaottini, F.; Picasso, R.; Pistoia, F.; Sanguinetti, S.; Pansecchi, M.; Tovt, L.; Viglino, U.; Cabona, C.; Garnero, M.; Benedetti, L.; et al. High-resolution ultrasound of peripheral neuropathies in rheumatological patients: An overview of clinical applications and imaging findings. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 984379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroc, M.; Lachhab, A.; Rhoul, A.; Harmouche, M.; EL Oumri, A.A. Wartenberg’s Syndrome: A Case of Ultrasound Revealing a Diagnosis Missed by Electromyography with Hydrodissection Offering Pain Relief and Functional Recovery. Cureus 2025, 17, e88503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirri, C.; Pirri, N.; Stecco, C.; Macchi, V.; Porzionato, A.; De Caro, R.; Özçakar, L. Hearing and Seeing Nerve/Tendon Snapping: A Systematic Review on Dynamic Ultrasound Examination. Sensors 2023, 23, 6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppieters, M.W.; Hough, A.D.; Dilley, A. Different Nerve-Gliding Exercises Induce Different Magnitudes of Median Nerve Longitudinal Excursion: An In Vivo Study Using Dynamic Ultrasound Imaging. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 39, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouda, B.H. Ultrasound Guided Carpel Tunnel Syndrome Hydrodissection; It’s All About It. J. Neurosonol. Neuroimaging 2023, 15, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, B.H.; Abdelwahed, W.M.; Negm, E.E. Ultrasound guided hydrodissection versus open surgery in patients with severe carpel tunnel syndrome: A randomized controlled study. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2025, 61, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.S.; Hung, C.-Y.; Chiang, Y.-P.; Onishi, K.; Su, D.C.J.; Clark, T.B.; Reeves, K.D. Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Hydrodissection for Pain Management: Rationale, Methods, Current Literature, and Theoretical Mechanisms. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, W.D., Jr. The role of TRPV1 receptors in pain evoked by noxious thermal and chemical stimuli. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 196, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.; Sheth, S.; Mukherjea, D.; Rybak, L.P.; Ramkumar, V. TRPV1: A Potential Drug Target for Treating Various Diseases. Cells 2014, 3, 517–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, E.S.; Fernandes, M.A.; Keeble, J.E. The functions of TRPA1 and TRPV1: Moving away from sensory nerves. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyftogt, J. Subcutaneous prolotherapy treatment of refractory knee, shoulder, and lateral elbow pain. Australas. Musculoskelet. Med. 2007, 12, 110. [Google Scholar]

| Timepoint | EPL Distal Motor Latency (ms) | CMAP Amplitude (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Pre-treatment) | 4.5 | 3.4 |

| Post-treatment (6 weeks) | 2.1 | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoon, Y.; Lam, K.H.S.; Castro, J.C.d.; Hwang, J.; Lee, J.; Suryadi, T.; Suhaimi, A.; Kang, C.-W.; Choi, J.; Kim, S. Ultrasound-Guided Dextrose Hydrodissection for Mixed Sensory–Motor Wartenberg’s Syndrome Following a Healed Scaphoid Fracture: A Case Report. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010156

Yoon Y, Lam KHS, Castro JCd, Hwang J, Lee J, Suryadi T, Suhaimi A, Kang C-W, Choi J, Kim S. Ultrasound-Guided Dextrose Hydrodissection for Mixed Sensory–Motor Wartenberg’s Syndrome Following a Healed Scaphoid Fracture: A Case Report. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010156

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Yonghyun, King Hei Stanley Lam, Jeimylo C. de Castro, Jihyo Hwang, Jaeyoung Lee, Teinny Suryadi, Anwar Suhaimi, Chun-Wei Kang, Jaeik Choi, and Seungbeom Kim. 2026. "Ultrasound-Guided Dextrose Hydrodissection for Mixed Sensory–Motor Wartenberg’s Syndrome Following a Healed Scaphoid Fracture: A Case Report" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010156

APA StyleYoon, Y., Lam, K. H. S., Castro, J. C. d., Hwang, J., Lee, J., Suryadi, T., Suhaimi, A., Kang, C.-W., Choi, J., & Kim, S. (2026). Ultrasound-Guided Dextrose Hydrodissection for Mixed Sensory–Motor Wartenberg’s Syndrome Following a Healed Scaphoid Fracture: A Case Report. Diagnostics, 16(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010156