Systemic Sclerosis-Associated ILD: Insights and Limitations of ScleroID

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

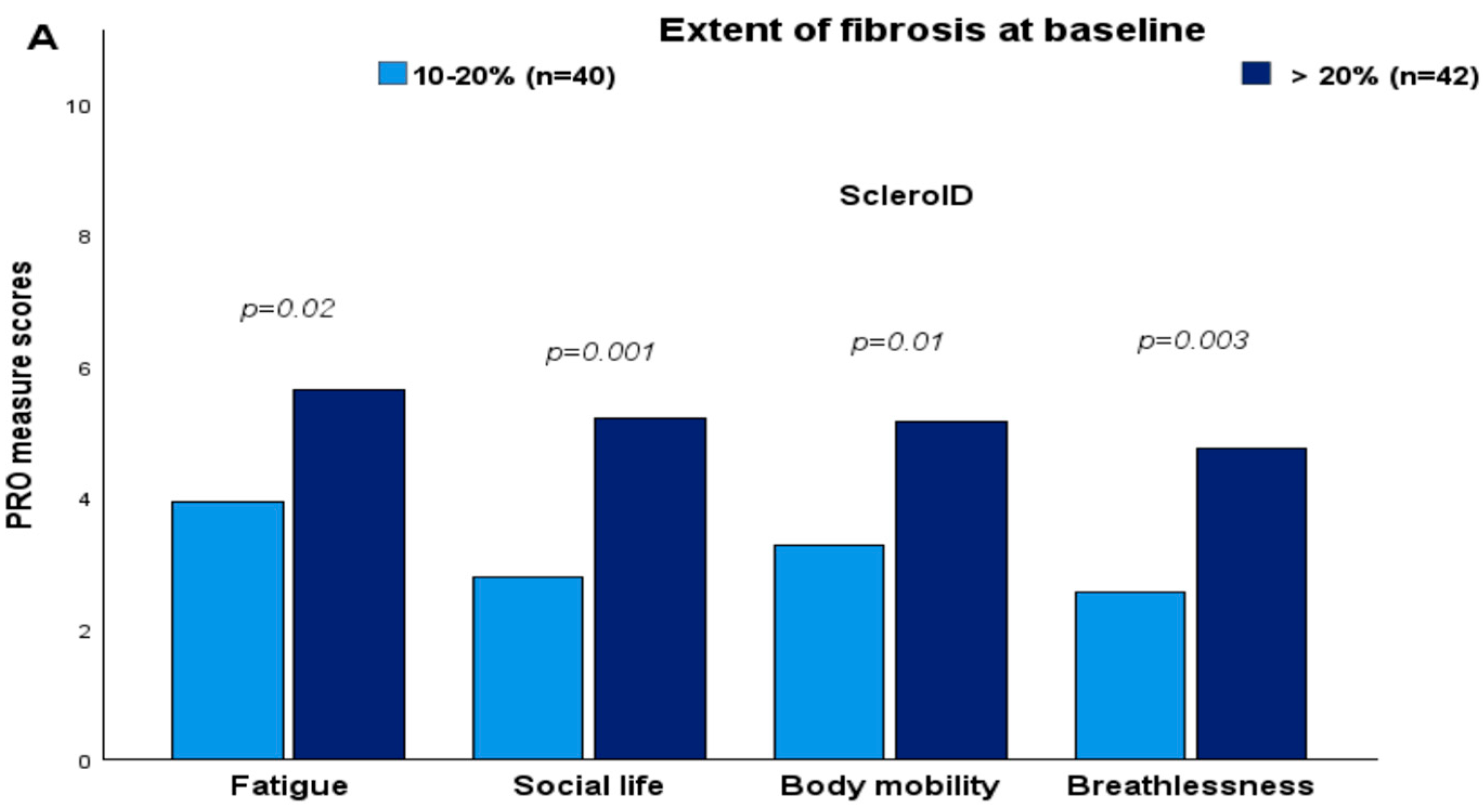

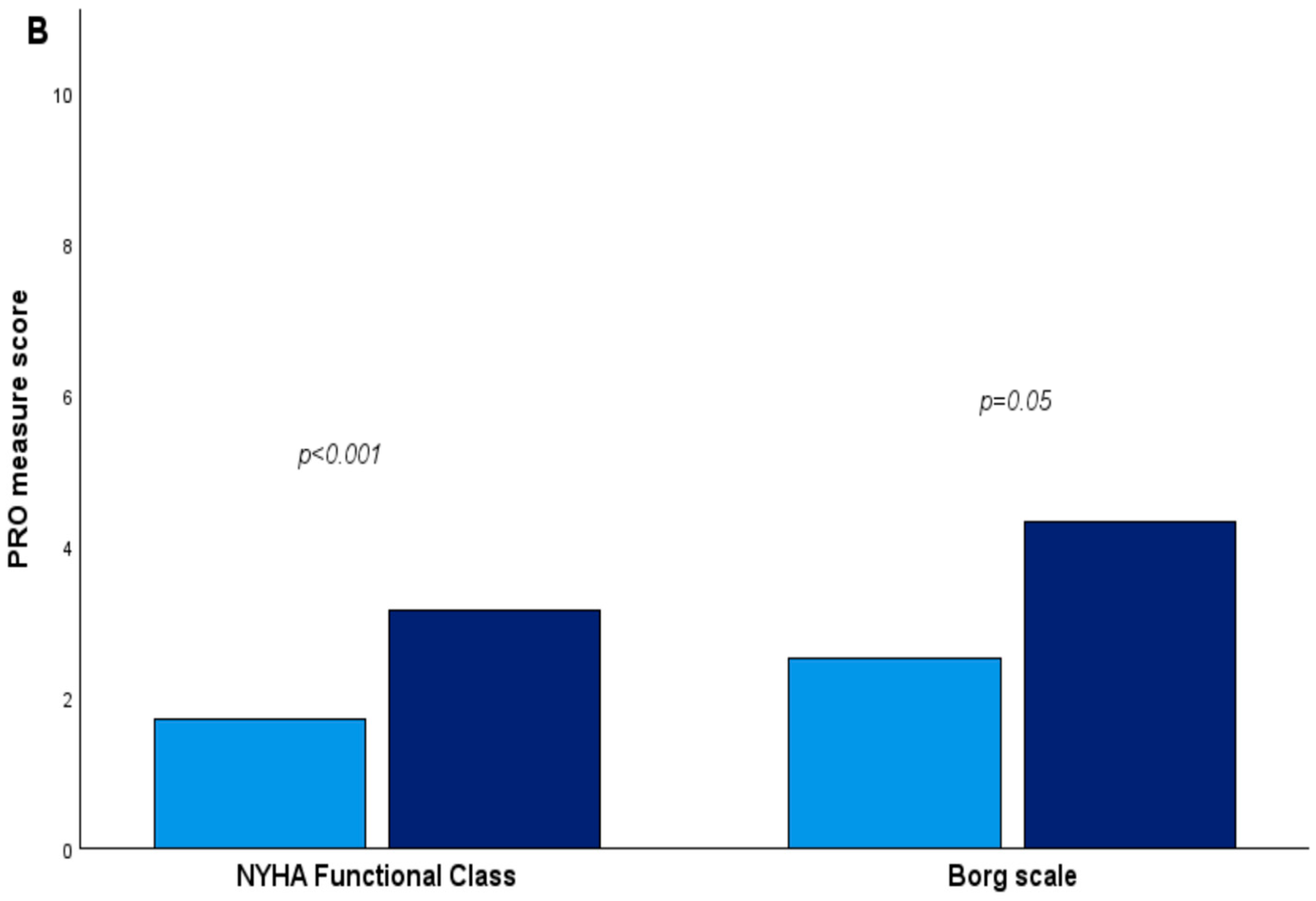

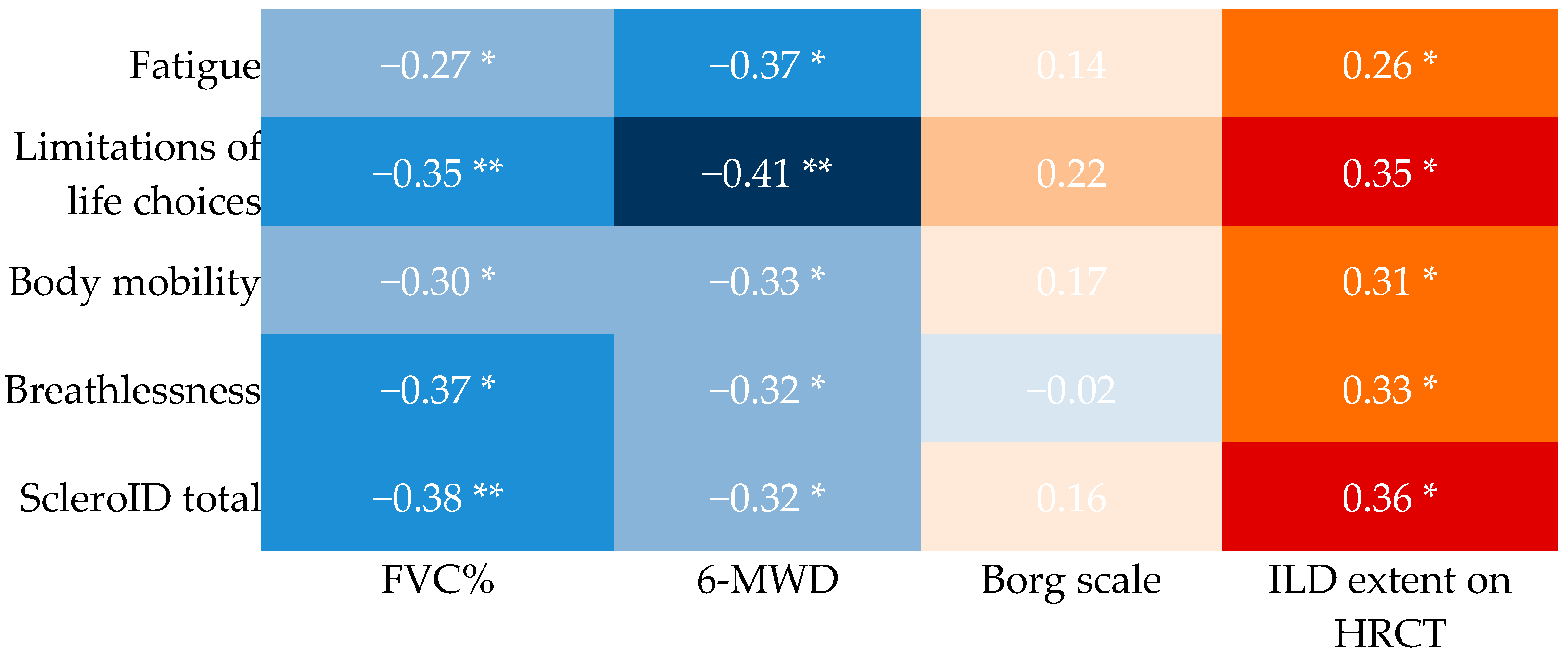

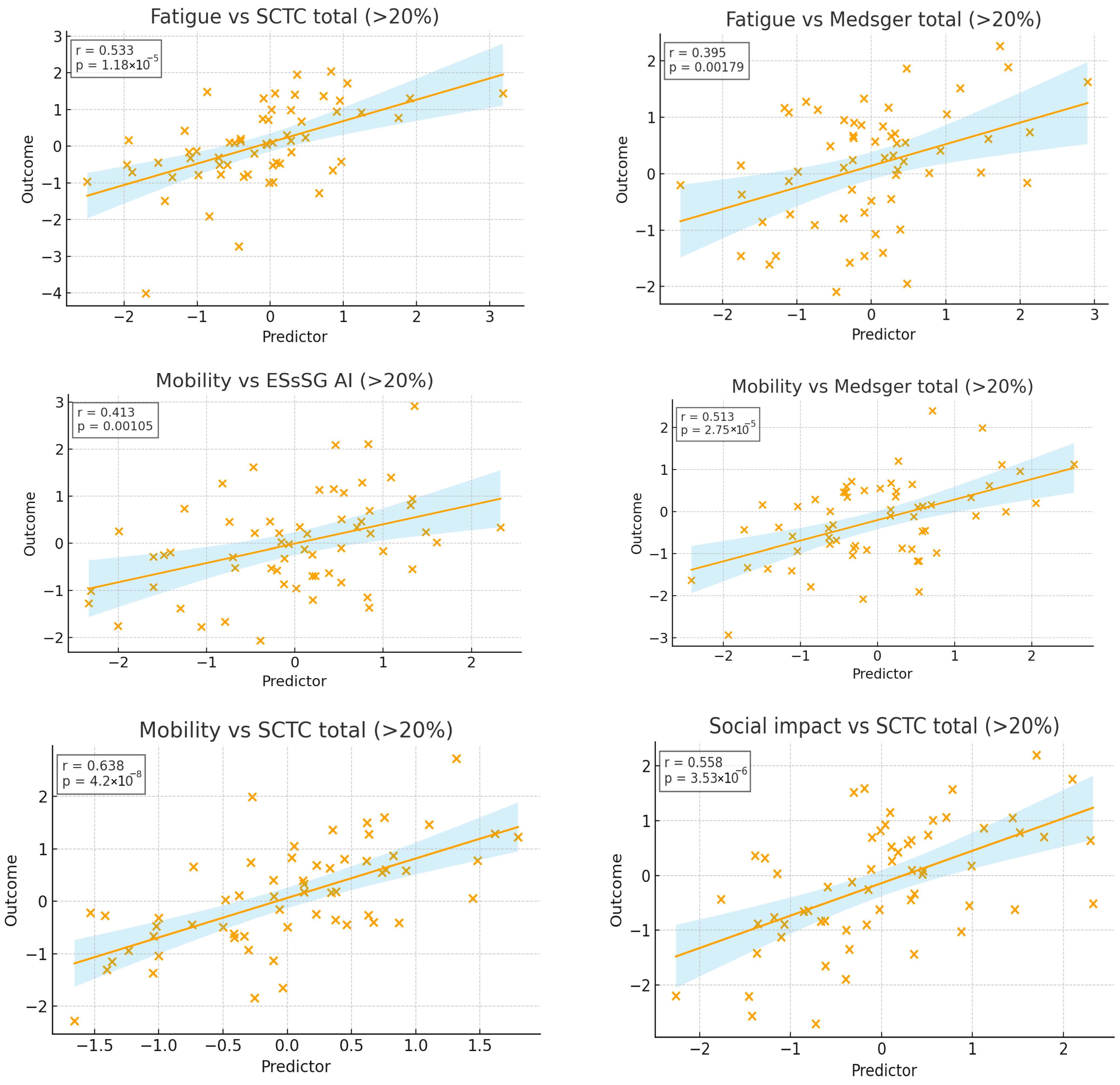

3.2. Cross-Sectional Associations Between ScleroID Items and Baseline Lung Parameters

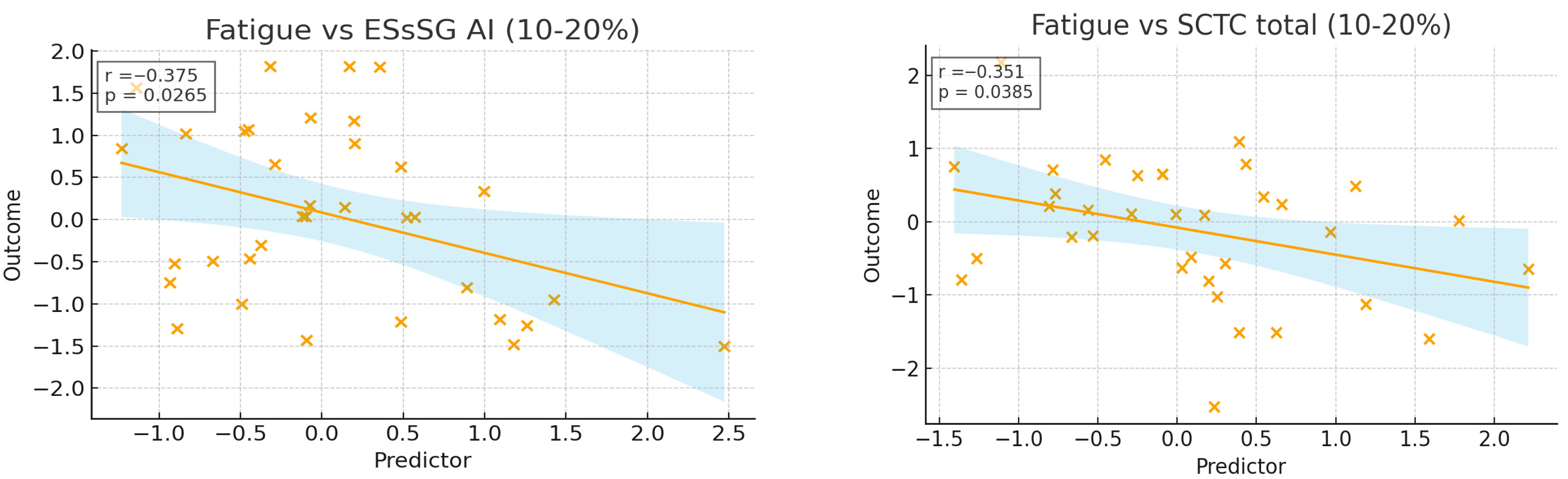

3.3. Impact of SSc Disease Activity and Damage on QoL in the Studied SSc-ILD Cohort

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSc | systemic sclerosis |

| PFR | pulmonary function tests |

| HRCT | high-resolution CT |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcomes |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| EScSG-AI | European Scleroderma Study Group Activity Index |

| SCTC-AI | Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index |

| MSS | Medsger severity scale |

| FVC | forced volume capacity |

| DLCO | diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide |

| ATA | antitopoisomerase 1 antibodies |

| 6-MWT | 6 min walking test |

| QoL | quality of life |

| ScleroID | EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease |

| RHC | right heart catheterization |

| PH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| dcSSc | diffuse cutaneous form of systemic sclerosis |

| lcSSc | limited cutaneous form of systemic sclerosis |

References

- Allanore, Y.; Simms, R.; Distler, O.; Trojanowska, M.; Pope, J.; Denton, C.P.; Varga, J. Systemic sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer. 2015, 1, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Scirè, C.A.; Talarico, R.; Airo, P.; Alexander, T.; Allanore, Y.; Bruni, C.; Codullo, V.; Dalm, V.; De Vries-Bouwstra, J.; et al. Systemic sclerosis: State of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open 2019, 4, e000782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcolea, M.P.; Starita Fajardo, G.; Peña Rodríguez, M.; Lucena López, D.; Suárez Carantoña, C.; López Paraja, M.; García de Vicente, A.; Viteri-Noël, A.; González García, A. Advances in the Molecular Mechanisms of Pulmonary Fibrosis in Systemic Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Thevissen, K.; Trombetta, A.C.; Pizzorni, C.; Ruaro, B.; Piette, Y.; Paolino, S.; De Keyser, F.; Sulli, A.; Melsens, K.; et al. Nailfold Capillaroscopy and Clinical Applications in Systemic Sclerosis. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Petelytska, L.; Fretheim, H.; Aaløkken, T.M.; Becker, M.O.; Jenssen Bjørkekjær, H.; Brunborg, C.; Bruni, C.; Clarenbach, C.; Diep, P.P.; et al. Predicting the risk of subsequent progression in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease with progression: A multicentre observational cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2025, 7, e463–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roofeh, D.; Brown, K.K.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Tashkin, D.; Assassi, S.; Martinez, F.; Wells, A.U.; Raghu, G.; Denton, C.P.; Chung, L.; et al. Systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease: A conceptual framework for subclinical, clinical and progressive disease. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakouli, V.; Ciancio, A.; Del Galdo, F.; Giacomelli, R.; Ciccia, F. Systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease: Unmet needs and potential solutions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Bernstein, E.J.; Bolster, M.B.; Chung, J.H.; Danoff, S.K.; George, M.D.; Khanna, D.; Guyatt, G.; Mirza, R.D.; Aggarwal, R.; et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 2024, 76, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.J.S.; Jee, A.S.; Hansen, D.; Proudman, S.; Youssef, P.; Kenna, T.J.; Stevens, W.; Nikpour, M.; Sahhar, J.; Corte, T.J. Multiple serum biomarkers associate with mortality and interstitial lung disease progression in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 2981–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Allanore, Y.; Bendstrup, E.; Bruni, C.; Distler, O.; Maher, T.M.; Wijsenbeek, M.; Kreuter, M. The need for a holistic approach for SSc-ILD—Achievements and ambiguity in a devastating disease. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvaides, T.M.; Di Vitantonio, T.A.; Edgar, A.; O’Beirne, R.; Krishnan, J.K.; Kaner, R.J.; Podolanczuk, A.J.; Spiera, R.; Gordon, J.; Safford, M.M.; et al. Patient perspectives on educational needs in scleroderma-interstitial lung disease. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2025, 10, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleto, G.; Santiago, T.; Sieiro Santos, C. Editorial: Advances in understanding and managing systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: Bridging prognostic biomarkers to therapeutic innovations. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1683554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, G.; Bencivelli, W.; Bombardieri, S.; D’Angelo, S.; Della Rossa, A.; Silman, A.J.; Black, C.M.; Czirjak, L.; Nielsen, H.; Vlachoyiannopoulos, P.G. European Scleroderma Study Group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. III. Assessment of the construct validity of the preliminary activity criteria. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003, 62, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.; Hansen, D.; Proudman, S.; Khanna, D.; Herrick, A.L.; Stevens, W.; Baron, M.; Nikpour, M.; Australian Scleroderma Interest Group (ASIG); Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG); et al. Development and Initial Validation of the Novel Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Activity Index. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medsger, T.A.; Silman, A.J.; Steen, V.D.; Black, C.M.; Akesson, A.; Bacon, P.A.; Harris, C.A.; Jablonska, S.; Jayson, M.I.; Jimenez, S.A.; et al. A disease severity scale for systemic sclerosis: Development and testing. J. Rheumatol. 1999, 26, 2159–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.W.; Quirk, F.H.; Baveystock, C.M.; Littlejohns, P. A Self-complete Measure of Health Status for Chronic Airflow Limitation: The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1992, 145, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Patel, A.S.; Siegert, R.J.; Bajwah, S.; Maher, T.M.; Renzoni, E.A.; Wells, A.U.; Higginson, I.J.; Birring, S.S. The King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease (KBILD) questionnaire: An updated minimal clinically important difference. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2019, 6, e000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchcliff, M.; Beaumont, J.L.; Thavarajah, K.; Varga, J.; Chung, A.; Podlusky, S.; Carns, M.; Chang, R.W.; Cella, D. Validity of two new patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis: Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system 29-item health profile and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–dyspnea short form. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mchorney, C.A.; Johne, W.; Anastasiae, R. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and Clinical Tests of Validity in Measuring Physical and Mental Health Constructs. Med. Care 1993, 31, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allanore, Y.; Bozzi, S.; Terlinden, A.; Huscher, D.; Amand, C.; Soubrane, C.; Siegert, E.; Czirják, L.; Carreira, P.E.; Hachulla, E.; et al. Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) use in modelling disease progression in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: An analysis from the EUSTAR database. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.J.; Namas, R.; Seelman, D.; Jaafar, S.; Homer, K.; Wilhalme, H.; Young, A.; Nagaraja, V.; White, E.S.; Schiopu, E.; et al. Reliability, construct validity and responsiveness to change of the PROMIS-29 in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Distler, O.; Highland, K.B.; Gahlemann, M.; Azuma, A.; Fischer, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Raghu, G.; Sauter, W.; Girard, M.; Alves, M.; et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, P.A.; Herlyn, K.; Martin, R.W.; Anderson, J.J.; Mayes, M.D.; Bell, P.; Korn, J.H.; Simms, R.W.; Csuka, M.E.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; et al. Measuring disease activity and functional status in patients with scleroderma and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2410–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Tseng, C.H.; Furst, D.E.; Clements, P.J.; Elashoff, R.; Roth, M.; Elashoff, D.; Tashkin, D.P. Minimally important differences in the Mahler’s Transition Dyspnoea Index in a large randomized controlled trial—Results from the Scleroderma Lung Study. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birring, S.S. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003, 58, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, T.J.; Mahler, D.A. Minimal important difference of the transition dyspnoea index in a multinational clinical trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 21, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponniah, T.; Wong, C.K.; Ng, C.M.; Raja, J. Quality of life in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease and its association with respiratory clinical parameters. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2025, 10, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanet: ATHENA-SSc-ILD: A Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of PRA023 in Subjects with Systemic Sclerosis Associated with Interstitial Lung Disease (SSc-ILD)-PL. 2025. Available online: http://www.orpha.net/en/research-trials/clinical-trial/674705?country=&mode=&name=&recruiting=0&terminated=0 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Becker, M.O.; Dobrota, R.; Garaiman, A.; Debelak, R.; Fligelstone, K.; Tyrrell Kennedy, A.; Roennow, A.; Allanore, Y.; Carreira, P.E.; Czirják, L.; et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for systemic sclerosis: The EULAR Systemic Sclerosis Impact of Disease (ScleroID) questionnaire. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, S.Y.; Di Donato, S.; Bixio, R.; Bissell, L.A.; Barnes, T.; Nisar, M.; Kakkar, V.; Denton, C.; Del Galdo, F. Cross-validation and sensitivity to change of EULAR ScleroID as a measure of function and impact of disease in patients with systemic sclerosis. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Montesi, S.B.; Silver, R.M.; Hossain, T.; Macrea, M.; Herman, D.; Barnes, H.; Adegunsoye, A.; Azuma, A.; Chung, L.; et al. Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis-associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Evidence-based Recommendations. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, K.M.; Distler, O.; Gheorghiu, A.M.; Moor, C.C.; Vikse, J.; Bizymi, N.; Galetti, I.; Brown, G.; Bargagli, E.; Allanore, Y.; et al. ERS/EULAR clinical practice guidelines for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease developed by the task force for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Endorsed by the European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Hoogen, F.; Khanna, D.; Fransen, J.; Johnson, S.R.; Baron, M.; Tyndall, A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Naden, R.P.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; Carreira, P.E.; et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: An American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansell, D.M.; Bankier, A.A.; MacMahon, H.; McLoud, T.C.; Müller, N.L.; Remy, J. Fleischner Society: Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging. Radiology 2008, 246, 697–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Tammeling, G.J.; Cotes, J.E.; Pedersen, O.F.; Peslin, R.; Yernault, J.C. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Eur. Respir. J. 1993, 6, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennøe, A.H.; Murbræch, K.; Andreassen, J.C.; Fretheim, H.; Garen, T.; Gude, E.; Andreassen, A.; Aakhus, S.; Molberg, Ø.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M. Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction Predicts Mortality in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Beghetti, M.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 67–119. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, N.S.; Hoyles, R.K.; Denton, C.P.; Hansell, D.M.; Renzoni, E.A.; Maher, T.M.; Nicholson, A.G.; Wells, A.U. Short-Term Pulmonary Function Trends Are Predictive of Mortality in Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Mittoo, S.; Aggarwal, R.; Proudman, S.M.; Dalbeth, N.; Matteson, E.L.; Brown, K.; Flaherty, K.; Wells, A.U.; Seibold, J.R.; et al. Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Diseases (CTD-ILD)—Report from OMERACT CTD-ILD Working Group. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 2168–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Zappala, C.J.; Latsi, P.I.; Nicholson, A.G.; Colby, T.V.; Cramer, D.; Renzoni, E.A.; Hansell, D.M.; du Bois, R.M.; Wells, A.U. Marginal decline in forced vital capacity is associated with a poor outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 35, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescoat, A.; Huscher, D.; Schoof, N.; Airò, P.; De Vries-Bouwstra, J.; Riemekasten, G.; Hachulla, E.; Doria, A.; Rosato, E.; Hunzelmann, N.; et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database: Analysis by region. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 2178–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Allanore, Y.; Alves, M.; Brunborg, C.; Airó, P.; Ananieva, L.P.; Czirják, L.; Guiducci, S.; Hachulla, E.; Li, M. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrota, R.; Becker, M.O.; Fligelstone, K.; Fransen, J.; Tyrrell Kennedy, A.; Allanore, Y.; Roennow, A.; Allanore, Y.; Carreira, P.E.; Czirják, L. AB0787 The eular systemic sclerosis impact of disease (SCLEROID) score—A new patient-reported outcome measure for patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, A.C.; Weber, J.M.; Todd, J.L.; Palmer, S.M.; Neely, M.L.; Whelan, T.P.; Kim, G.H.J.; Leonard, T.B.; Goldin, J. Extent of lung fibrosis is of greater prognostic importance than HRCT pattern in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis: Data from the ILD-PRO registry. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuter, M.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Saketkoo, L.A.; Highland, K.B.; Wilson, H.; Alves, M.; Erhardt, E.; Schoof, N.; Maher, T.M. Impact of lung function and baseline clinical characteristics on patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology 2023, 62, SI43–SI53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giubertoni, A.; Bellan, M.; Cumitini, L.; Patti, G. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing: Deciphering Cardiovascular Complications in Systemic Sclerosis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 25914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petelytska, L.; Bonomi, F.; Cannistrà, C.; Fiorentini, E.; Peretti, S.; Torracchi, S.; Bernardini, P.; Coccia, C.; De Luca, R.; Economou, A. Heterogeneity of determining disease severity, clinical course and outcomes in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: A systematic literature review. RMD Open 2023, 9, e003426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Kratz, A.L.; Whibley, D.; Poole, J.L.; Khanna, D. Fatigue and Its Association with Social Participation, Functioning, and Quality of Life in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellar, R.E.; Tingey, T.M.; Pope, J.E. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma). Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 42, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeser, A.; Brillet, P.Y.; Tran Ba, S.; Caux, F.; Dhote, R.; Nunes, H.; Uzunhan, Y. The importance of considering progression speed in systemic sclerosis—Associated interstitial lung diseases: Application of 2022 and 2024 clinical practice guidelines for progressive pulmonary fibrosis, a retrospective cohort study. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.; Teichgräber, U.; Brüheim, L.B.; Lassen-Schmidt, B.; Renz, D.; Weise, T.; Krämer, M.; Oelzner, P.; Böttcher, J.; Güttler, F.; et al. The association of symptoms, pulmonary function test and computed tomography in interstitial lung disease at the onset of connective tissue disease: An observational study with artificial intelligence analysis of high-resolution computed tomography. Rheumatol. Int. 2025, 45, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Baseline Mean (SD) Composite Measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | EscSG-AI | SCTC-AI | MSS | ScleroID |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n = 68) | 6.1 (2.2) | 34.0 (15.6) | 8.9 (3.9) | 4.0 (2.2) |

| Male (n = 14) | 5.6 (1.8) | 34.5 (15.8) | 9.7 (3.1) | 4.1 (2.6) |

| Age | ||||

| <65 years (n = 59) | 6.0 (2.2) | 33.5 (14.8) | 9.7 (3.8) | 4.1 (2.3) |

| ≥65 years (n = 23) | 6.2 (2.1) | 37.7 (17.9) | 9.3 (3.8) | 3.8 (2.2) |

| SSc subset | ||||

| dcSSc (n = 44) | 6.2 (2.1) | 37.1 (15.8) | 10.2 (4.1) | 4.5 (2.4) |

| lcSSc(n = 38) | 5.8 (2.0) | 30.8 (13.9) | 8.9 (3.3) | 3.6 (2.1) |

| SSc disease duration a | ||||

| ≤3 years (n = 43) | 5.8 (1.8) | 32.1 (13.2) | 9.1 (3.7) | 4.0 (2.3) |

| >3 years (n = 39) | 6.3 (1.6) | 36.9 (16.0) | 10.2 (3.8) | 4.2 (2.4) |

| Autoantibodies | ||||

| Anti-centromere (n = 14) | 5.5 (1.9) | 32.3 (13.6) | 9.4 (3.8) | 4.5 (2.3) |

| Anti-toposiomerase (n = 54) | 6.4 (1.5) | 35.6 (15.3) | 9.8 (3.8) | 3.8 (2.3) |

| 6-MWD desaturation < 94% OR ≥ 5% b | ||||

| Yes (n = 21) | 5.6 (1.9) | 35.2 (14.3) | 9.2 (3.7) | 4.2 (2.3) |

| No (n = 22) | 6.2 (1.6) | 32.5 (14.5) | 9.7 (3.9) | 3.9 (2.5) |

| Unexplained dyspnea functional class 3 or 4 | ||||

| Yes (n = 31) | 5.3 (1.9) | 30.9 (12.3) | 8.4 (3.8) | 3.6 (2.0) |

| No (n = 51) | 6.3 (1.6) | 34.5 (15.0) | 9.8 (3.7) | 4.0 (2.6) |

| FVC % predicted at baseline | ||||

| <80% (n = 53) | 5.6 (1.9) | 33.1 (14.1) | 8.9 (3.8) | 3.5 (2.3) |

| ≥80% (n = 29) | 6.5 (1.4) | 34.1 (16.4) | 10.4 (4.0) | 4.0 (2.3) |

| >10% FVC decline on follow-up PFT | ||||

| Yes (n = 45) | 6.3 (1.6) | 35.1 (15.9) | 10.1 (4.1) | 4.3 (2.5) |

| No (n = 37) | 5.7 (1.8) | 33 (13.4) | 9.0 (3.5) | 3.7 (2.1) |

| Extent of fibrosis by HRCT | ||||

| 10–20% (n = 40) | 5.5 (1.7) | 28.8 (12.5) | 7.4 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.1) |

| ≥20% (n = 42) | 6.7 (1.4) | 40.2 (14.6) | 11.6 (3.7) | 4.8 (2.3) |

| PH | ||||

| Yes (n = 29) | 6.4 (1.7) | 44.2 (13.8) | 12.1 (3.8) | 4.8 (2.1) |

| No (n = 53) | 5.9 (1.7) | 29.1 (12.4) | 8.3 (3.1) | 3.7 (2.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niță, C.; Groșeanu, L. Systemic Sclerosis-Associated ILD: Insights and Limitations of ScleroID. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010158

Niță C, Groșeanu L. Systemic Sclerosis-Associated ILD: Insights and Limitations of ScleroID. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010158

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiță, Cristina, and Laura Groșeanu. 2026. "Systemic Sclerosis-Associated ILD: Insights and Limitations of ScleroID" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010158

APA StyleNiță, C., & Groșeanu, L. (2026). Systemic Sclerosis-Associated ILD: Insights and Limitations of ScleroID. Diagnostics, 16(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010158