BacT-Seq, a Nanopore-Based Whole-Genome Sequencing Workflow Prototype for Rapid and Accurate Pathogen Identification and Resistance Prediction from Positive Blood Cultures: A Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Samples and Design

2.2. Blood Culture

2.3. Reference Pipeline for Phenotypic Microbial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.3.1. Microbial Identification by Reference Method

2.3.2. Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. BacT-Seq Sequencing Pipeline for Genotypic Microbial Identification and Antimicrobial Resistance Detection and/or Prediction

2.4.1. BacT-Seq Pipeline Description

2.4.2. Microbial DNA Enrichment

2.4.3. Sample Preparation and Sequencing

2.4.4. Microbial Identification by BacT-Seq

2.4.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Determinant Detection by Direct Association

2.4.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Prediction Models

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

2.5.2. Time-to-Result (TTR) Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Microbial Samples According to Reference Methods

3.1.1. Reference Identification of Microbial Samples

3.1.2. Reference Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

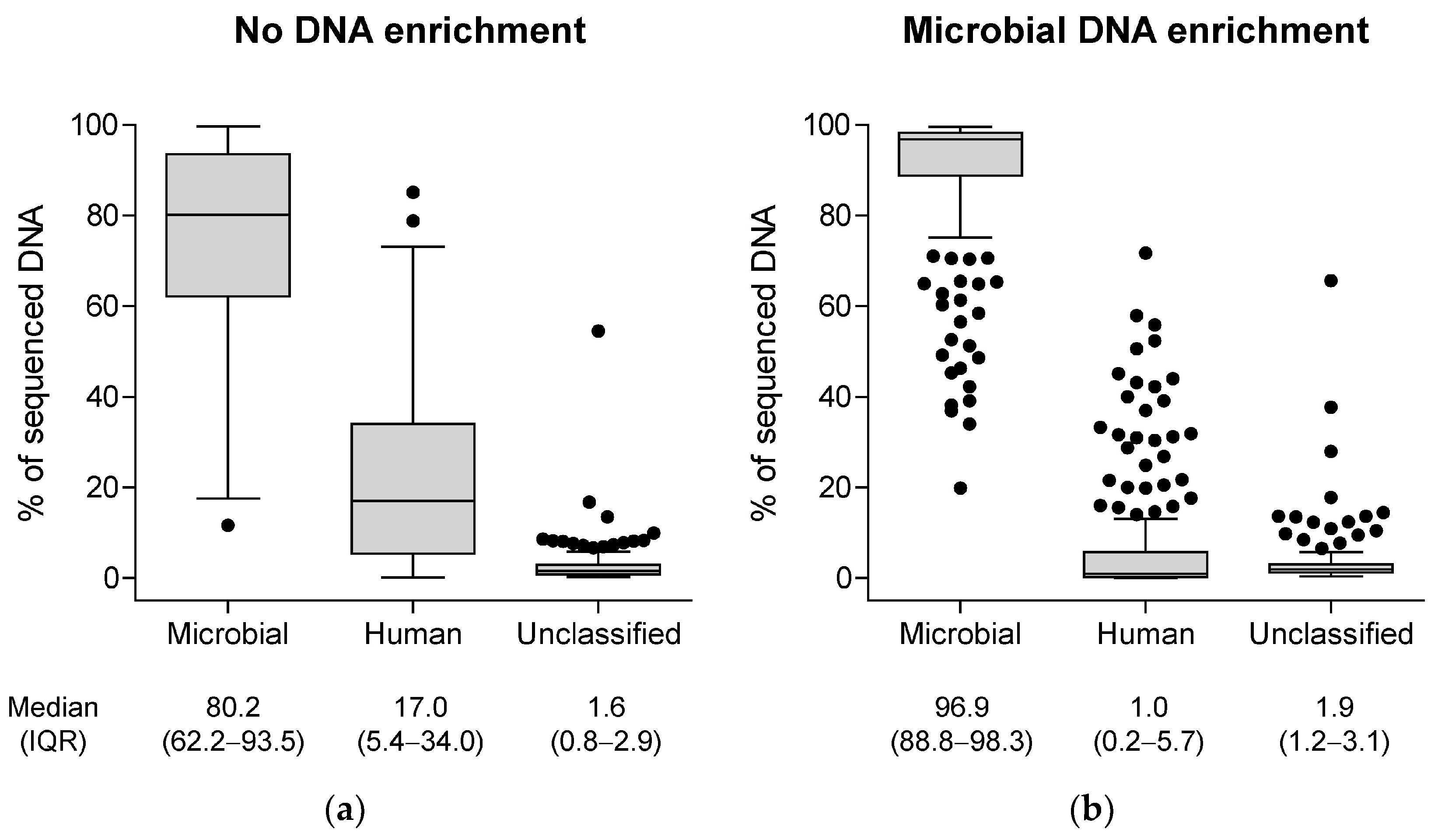

3.2. Genotypic Characterization of Microbial Samples by the BacT-Seq Sequencing Platform: Sample Preparation

3.3. Performance of BacT-Seq-Based Microbial Identification vs. Reference Identification

3.3.1. Mono-Microbial Samples

3.3.2. Poly-Microbial Samples

3.3.3. Time to Microbial Identification by BacT-Seq

3.4. Performance of BacT-Seq-Based Antimicrobial Resistance Determinant Detection vs. Reference Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

3.5. Performance of BacT-Seq-Based Antimicrobial Susceptibility Prediction Models vs. Reference Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

3.5.1. ASP Signature for S. aureus

3.5.2. ASP Signature for K. pneumoniae

3.5.3. ASP Signature for E. coli

3.5.4. ASP Signature for P. aeruginosa

3.6. Time to ASP Using the BacT-Seq Pipeline

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Sepsis Incidence and Mortality, 1990-2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.P.; Carvalho, C.M. Burden of Bacterial Bloodstream Infections and Recent Advances for Diagnosis. Pathog. Dis. 2022, 80, ftac027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable Deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years Caused by Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A Population-Level Modelling Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kraker, M.E.A.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 Million People Die a Year Due to Antimicrobial Resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauba, A.; Rahman, K.M. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buehler, S.S.; Madison, B.; Snyder, S.R.; Derzon, J.H.; Cornish, N.E.; Saubolle, M.A.; Weissfeld, A.S.; Weinstein, M.P.; Liebow, E.B.; Wolk, D.M. Effectiveness of Practices To Increase Timeliness of Providing Targeted Therapy for Inpatients with Bloodstream Infections: A Laboratory Medicine Best Practices Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 29, 59–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinski, M.A.; Alby, K.; Babady, N.E.; Butler-Wu, S.M.; Bard, J.D.; Greninger, A.L.; Hanson, K.; Naccache, S.N.; Newton, D.; Temple-Smolkin, R.L.; et al. Exploring the Utility of Multiplex Infectious Disease Panel Testing for Diagnosis of Infection in Different Body Sites: A Joint Report of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society for Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. J. Mol. Diagn. JMD 2023, 25, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatli-Kis, T.; Yildirim, S.; Bicmen, C.; Kirakli, C. Early Detection of Bacteremia Pathogens with Rapid Molecular Diagnostic Tests and Evaluation of Effect on Intensive Care Patient Management. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 110, 116424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.; Balgahom, R.; Janto, C.; Polkinghorne, A.; Branley, J. Evaluation of the BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel and Impact on Patient Management and Antimicrobial Stewardship. Pathology 2021, 53, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.D.; Zhan, M.; Zhang, S.; Leekha, S.; Harris, A.; Doi, Y.; Evans, S.; Kristie Johnson, J.; Ernst, R.K. Comparison of Three Rapid Diagnostic Tests for Bloodstream Infections Using Benefit-Risk Evaluation Framework (BED-FRAME). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.D.; Pournaras, S.; Leber, A.; Balada-Llasat, J.-M.; Harrington, A.; Sambri, V.; She, R.; Berry, G.J.; Daly, J.; Good, C.; et al. Multicenter Evaluation of the BIOFIRE Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel for Detection of Bacteria, Yeasts, and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Positive Blood Culture Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0189122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, A.M.; Ling, W.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Harris, P.N.A.; Paterson, D.L. Performance of BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel (BCID2) for the Detection of Bloodstream Pathogens and Their Associated Resistance Markers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peri, A.M.; Bauer, M.J.; Bergh, H.; Butkiewicz, D.; Paterson, D.L.; Harris, P.N. Performance of the BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel for the Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, C.; Consonni, A.; Briozzo, E.; Giubbi, C.; Meroni, E.; Tonolo, S.; Luzzaro, F. Microbiological Assessment of the FilmArray Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel: Potential Impact in Critically Ill Patients. Antibiot. Basel Switz. 2023, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Yun, S.G.; Cho, Y.; Lee, C.K.; Nam, M.-H. Rapid Direct Identification of Microbial Pathogens and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Positive Blood Cultures Using a Fully Automated Multiplex PCR Assay. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnars, A.; Mahieu, R.; Declerck, C.; Chenouard, R.; Lemarié, C.; Pailhoriès, H.; Requin, J.; Kempf, M.; Eveillard, M. BIOFIRE® Blood Culture IDentification 2 (BCID2) Panel for Early Adaptation of Antimicrobial Therapy in Adult Patients with Bloodstream Infections: A Real-Life Experience. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 105, 115858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Tseng, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liang, S.-J.; Tu, C.-Y.; Chen, W.-C.; Hsueh, P.-R. The Real-World Impact of the BioFire FilmArray Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel on Antimicrobial Stewardship among Patients with Bloodstream Infections in Intensive Care Units with a High Burden of Drug-Resistant Pathogens. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinson, B.; Both, A.; Berneking, L.; Christner, M.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Rohde, H. Usefulness of BioFire FilmArray BCID2 for Blood Culture Processing in Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0054321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senok, A.; Dabal, L.A.; Alfaresi, M.; Habous, M.; Celiloglu, H.; Bashiri, S.; Almaazmi, N.; Ahmed, H.; Mohmed, A.A.; Bahaaldin, O.; et al. Clinical Impact of the BIOFIRE Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel in Adult Patients with Bloodstream Infection: A Multicentre Observational Study in the United Arab Emirates. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2023, 13, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.J.; Peri, A.M.; Lüftinger, L.; Beisken, S.; Bergh, H.; Forde, B.M.; Buckley, C.; Cuddihy, T.; Tan, P.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Optimized Method for Bacterial Nucleic Acid Extraction from Positive Blood Culture Broth for Whole-Genome Sequencing, Resistance Phenotype Prediction, and Downstream Molecular Applications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Johansen, W.; Ahmad, R. Short Turnaround Time of Seven to Nine Hours from Sample Collection until Informed Decision for Sepsis Treatment Using Nanopore Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avershina, E.; Frye, S.A.; Ali, J.; Taxt, A.M.; Ahmad, R. Ultrafast and Cost-Effective Pathogen Identification and Resistance Gene Detection in a Clinical Setting Using Nanopore Flongle Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 822402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taxt, A.M.; Avershina, E.; Frye, S.A.; Naseer, U.; Ahmad, R. Rapid Identification of Pathogens, Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Plasmids in Blood Cultures by Nanopore Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.N.A.; Bauer, M.J.; Lüftinger, L.; Beisken, S.; Forde, B.M.; Balch, R.; Cotta, M.; Schlapbach, L.; Raman, S.; Shekar, K.; et al. Rapid Nanopore Sequencing and Predictive Susceptibility Testing of Positive Blood Cultures from Intensive Care Patients with Sepsis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0306523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, O.; Almuhayawi, M.; Lüthje, P.; Taha, R.; Ullberg, M.; Özenci, V. Controlled Evaluation of the New BacT/Alert Virtuo Blood Culture System for Detection and Time to Detection of Bacteria and Yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1148–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.D.; Hanson, N.D.; Reedy, K.; Gafsi, J.; Ying, Y.X.; Hardy, D.J. First Description of the Performance of the VITEK MITUBE Device Used with MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry to Achieve Identification of Gram-Negative Bacteria Directly from Positive Blood Culture Broth. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0012225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; D’Hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: Visualizing and Processing Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2666–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) AMRFinderPlus—Pathogen Detection—NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/antimicrobial-resistance/AMRFinder/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Florensa, A.F.; Kaas, R.S.; Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aytan-Aktug, D.; Aarestrup, F.M. ResFinder—An Open Online Resource for Identification of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in next-Generation Sequencing Data and Prediction of Phenotypes from Genotypes. Microb. Genomics 2022, 8, 000748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Allesøe, R.; Joensen, K.G.; Cavaco, L.M.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M. PointFinder: A Novel Web Tool for WGS-Based Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Associated with Chromosomal Point Mutations in Bacterial Pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2764–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Gillespie, J.J.; Wattam, A.R.; Cammer, S.A.; Gabbard, J.L.; Shukla, M.P.; Dalay, O.; Driscoll, T.; Hix, D.; Mane, S.P.; Mao, C.; et al. PATRIC: The Comprehensive Bacterial Bioinformatics Resource with a Focus on Human Pathogenic Species. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4286–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center | BV-BRC. Available online: https://www.bv-brc.org/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Friedman, J.H.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillard, M.; Palmieri, M.; van Belkum, A.; Mahé, P. Interpreting K-Mer–Based Signatures for Antibiotic Resistance Prediction. GigaScience 2020, 9, giaa110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, P.; Tournoud, M. Predicting Bacterial Resistance from Whole-Genome Sequences Using k-Mers and Stability Selection. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Jaillard, M.; Lima, L.; Tournoud, M.; Mahé, P.; van Belkum, A.; Lacroix, V.; Jacob, L. A Fast and Agnostic Method for Bacterial Genome-Wide Association Studies: Bridging the Gap between k-Mers and Genetic Events. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goig, G.A.; Blanco, S.; Garcia-Basteiro, A.L.; Comas, I. Contaminant DNA in Bacterial Sequencing Experiments Is a Major Source of False Genetic Variability. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, A.; Andini, N.; Yang, S. A ‘Culture’ Shift: Application of Molecular Techniques for Diagnosing Polymicrobial Infections. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonara, S.; Ardura, M.I. Citrobacter Species. In Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 5th ed.; Long, S.S., Prober, C.G., Fischer, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 827–829.e1. ISBN 978-0-323-40181-4. [Google Scholar]

- Datar, R.; Perrin, G.; Chalansonnet, V.; Perry, A.; Perry, J.D.; van Belkum, A.; Orenga, S. Automated Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Slow-Growing Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains in the Presence of Tetrazolium Salt WST-1. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 186, 106252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and Alternative Therapeutic Strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.; Tummala, A.; Agab, M.; Rodriguez-Nava, G. Gemella Morbillorum as the Culprit Organism of Post-Colonoscopy Necrotizing Perineal Soft Tissue Infection in a Diabetic Patient With Crohn’s Disease. J. Med. Cases 2022, 13, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.; Faris, M.E.; Abdalla, M.S.; Prasai, P.; Ali, E.; Stake, J. A Rare Pathogen of Bones and Joints: A Systematic Review of Osteoarticular Infections Caused by Gemella morbillorum. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2023, 15, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Velez, G.; Pereira, X.; Narula, A.; Kim, P.K. Gemella Morbillorum as a Source Bacteria for Necrotising Fasciitis of the Torso. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e231727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, E.J.C.; Merriam, C.V.; Claros, M.C.; Citron, D.M. Comparative Susceptibility of Gemella Morbillorum to 13 Antimicrobial Agents. Anaerobe 2022, 75, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, P.D.; Wolter, D.J.; Hanson, N.D. Antibacterial-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical Impact and Complex Regulation of Chromosomally Encoded Resistance Mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 582–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, S.P.; Whiteley, M. Microbe Profile: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Opportunistic Pathogen and Lab Rat. Microbiology 2020, 166, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, C.; Pu, Q.; Deng, X.; Lan, L.; Liang, H.; Song, X.; Wu, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, Virulence Factors, Antibiotic Resistance, Interaction with Host, Technology Advances and Emerging Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnihotri, S.N.; Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, N.; Windhager, J.; Tenje, M.; Andersson, D.I. Droplet Microfluidics-Based Detection of Rare Antibiotic-Resistant Subpopulations in Escherichia Coli from Bloodstream Infections. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halfawy, O.M.; Valvano, M.A. Antimicrobial Heteroresistance: An Emerging Field in Need of Clarity. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Number | Species 1 | Species 2 | Species 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Staphylococcus hominis | |

| 2 | Micrococcus luteus | Moraxella osloensis | |

| 3 | Enterococcus faecium | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | |

| 4 | Bacteroides fragilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Streptococcus intermedius |

| 5 | Candida glabrata | Candida krusei | |

| 6 | Enterococcus faecalis | Escherichia coli | |

| 7 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | |

| 8 | Bacteroides fragilis | Streptococcus constellatus | |

| 9 | Citrobacter braakii | Enterococcus casseliflavus | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| 10 | Enterococcus faecalis | Escherichia coli | |

| 11 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Serratia marcescens | |

| 12 | Enterococcus faecalis | Escherichia coli |

| Reference ID | BacT-Seq ID |

|---|---|

| Proteus vulgaris | Proteus vulgaris + Citrobacter koseri |

| Staphylococcus capitis | Staphylococcus capitis + Staphylococcus haemolyticus |

| Hafnia alvei | Hafnia alvei + Staphylococcus saprophyticus |

| Streptococcus anginosus | Streptococcus anginosus group + Streptococcus milleri |

| Reference ID | BacT-Seq ID | N |

|---|---|---|

| Enterobacter cloacae | Enterobacter hormaechei | 6 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella quasipneumoniae | 3 |

| Streptococcus mitis/oralis | Streptococcus oralis | 1 |

| Reference ID | BacT-Seq ID | N |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus anginosus | Streptococcus anginosus group | 1 |

| Streptococcus mitis/oralis | Streptococcus | 1 |

| Bacillus circulans | Bacillus | 1 |

| Prevotella buccae | Prevotella | 1 |

| Aggregatibacter segnis | Aggregatibacter aphrophilus | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens | Serratia ureilytica | 1 |

| Sample Number | Reference ID | BacT-Seq ID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staphylococcus epidermidis Staphylococcus hominis | Staphylococcus epidermidis Staphylococcus hominis |

| 2 | Staphylococcus epidermidis Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Staphylococcus epidermidis Stenotrophomonas maltophilia |

| 3 | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli |

| 4 | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli |

| 5 | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli | Enterococcus faecalis Escherichia coli |

| 6 | Bacteroides fragilis Streptococcus intermedius Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Bacteroides fragilis Streptococcus intermedius |

| 7 | Klebsiella oxytoca Citrobacter braakii Enterococcus casseliflavus | Klebsiella oxytoca Citrobacter freundii |

| 8 | Bacteroides fragilis Streptococcus constellatus | Bacteroides fragilis Streptococcus constellatus Gemella morbillorum |

| 9 | Moraxella osloensis Micrococcus luteus | Moraxella osloensis |

| 10 | Enterococcus faecium Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Enterococcus faecium |

| 11 | Candida glabrata Candida krusei | Candida glabrata |

| 12 | Serratia marcescens Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Serratia marcescens |

| ARD Analysis | Sensitivity 1 n/N (%) | Specificity 2 n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Drug-level associations | 351/880 (39.9%) | 2199/2466 (89.2%) |

| Family-level associations | 451/880 (51.2%) | 1931/2466 (78.3%) |

| Strain-Specific ASP Model | Sensitivity 1 n/N (%) | Specificity 2 n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 4/9 (44.4%) | 104/105 (99.0%) |

| K. pneumoniae | 4/8 (50.0%) | 135/143 (94.4%) |

| E. coli | 55/57 (96.5%) | 363/437 (83.1%) |

| P. aeruginosa | 24/48 (50.0%) | 97/100 (97.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Azami, M.E.; Lanet, V.; Beaulieu, C.; Griffon, A.; Schicklin, S.; Mahé, P.; Darnaud, M.; Helsmoortel, M.; Sentausa, E.; Saliou, A.; et al. BacT-Seq, a Nanopore-Based Whole-Genome Sequencing Workflow Prototype for Rapid and Accurate Pathogen Identification and Resistance Prediction from Positive Blood Cultures: A Feasibility Study. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010133

Azami ME, Lanet V, Beaulieu C, Griffon A, Schicklin S, Mahé P, Darnaud M, Helsmoortel M, Sentausa E, Saliou A, et al. BacT-Seq, a Nanopore-Based Whole-Genome Sequencing Workflow Prototype for Rapid and Accurate Pathogen Identification and Resistance Prediction from Positive Blood Cultures: A Feasibility Study. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010133

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzami, Meriem El, Véronique Lanet, Corinne Beaulieu, Aurélien Griffon, Stéphane Schicklin, Pierre Mahé, Marion Darnaud, Marion Helsmoortel, Erwin Sentausa, Adrien Saliou, and et al. 2026. "BacT-Seq, a Nanopore-Based Whole-Genome Sequencing Workflow Prototype for Rapid and Accurate Pathogen Identification and Resistance Prediction from Positive Blood Cultures: A Feasibility Study" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010133

APA StyleAzami, M. E., Lanet, V., Beaulieu, C., Griffon, A., Schicklin, S., Mahé, P., Darnaud, M., Helsmoortel, M., Sentausa, E., Saliou, A., Poncelet, M., Fleury, R., Ibranosyan, M., Vandenesch, F., & Santiago-Allexant, E. (2026). BacT-Seq, a Nanopore-Based Whole-Genome Sequencing Workflow Prototype for Rapid and Accurate Pathogen Identification and Resistance Prediction from Positive Blood Cultures: A Feasibility Study. Diagnostics, 16(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010133