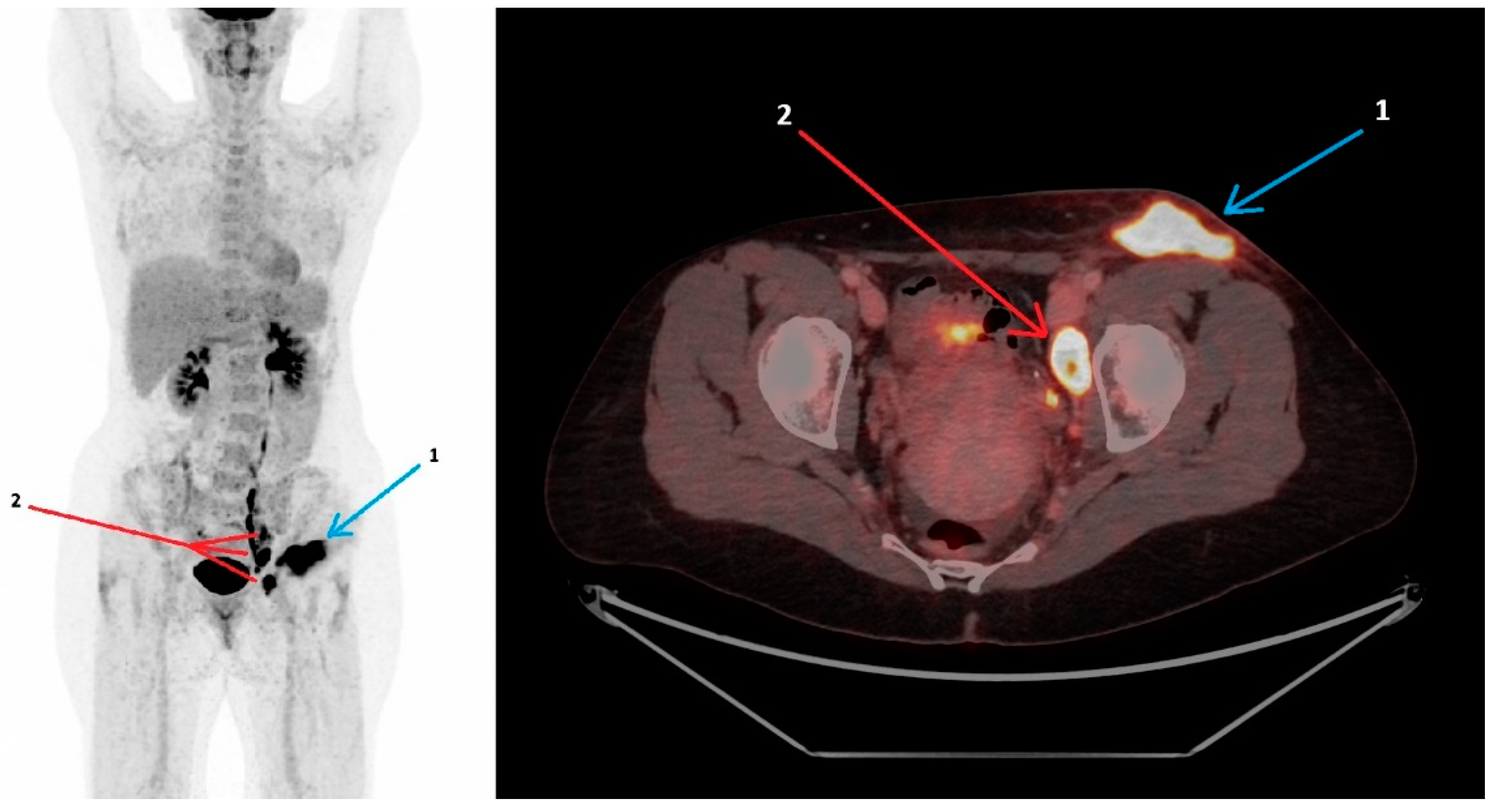

18F-FDG PET/CT Findings in Glandular Tularemia

Abstract

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foged, C.; Thorsteinsson, K.; Mens, H.; Helleberg, M.; Lebech, A.M. Tularaemia is often underdiagnosed. Ugeskr Laeger, 2025, in press.

- Nelson, C.A.; Winberg, J.; Bostic, T.D.; Davis, K.M.; Fleck-Derderian, S. Systematic Review: Clinical Features, Antimicrobial Treatment, and Outcomes of Human Tularemia, 1993–2023. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78 (Suppl. S1), S15–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonello, R.M.; Giacomelli, A.; Riccardi, N. Tularemia for clinicians: An up-to-date review on epidemiology, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tularaemia: Annual Epidemiological Report for 2019. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/tularaemia-annual-epidemiological-report-2019 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Maurin, M.; Pondérand, L.; Hennebique, A.; Pelloux, I.; Boisset, S.; Caspar, Y. Tularemia treatment: Experimental and clinical data. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1348323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinet, P.; Khatchatourian, L.; Saidani, N.; Fangous, M.S.; Goulon, D.; Lesecq, L.; Le Gall, F.; Guerpillon, B.; Corre, R.; Bizien, N.; et al. Hypermetabolic pulmonary lesions on FDG-PET/CT: Tularemia or neoplasia? Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravdal, A.; Stubhaug, Ø.O.; Wågø, A.G.; Sætereng, M.S.; Amundsen, D.; Piekuviene, R.; Kristiansen, A. Pulmonary tularaemia: A differential diagnosis to lung cancer. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00093–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gustafsson, F.; Rasmussen, K.K.; Thorsteinsson, K.; Lebech, A.-M.; Fjordside, L. 18F-FDG PET/CT Findings in Glandular Tularemia. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091159

Gustafsson F, Rasmussen KK, Thorsteinsson K, Lebech A-M, Fjordside L. 18F-FDG PET/CT Findings in Glandular Tularemia. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(9):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091159

Chicago/Turabian StyleGustafsson, Freja, Karl Keigo Rasmussen, Kristina Thorsteinsson, Anne-Mette Lebech, and Lasse Fjordside. 2025. "18F-FDG PET/CT Findings in Glandular Tularemia" Diagnostics 15, no. 9: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091159

APA StyleGustafsson, F., Rasmussen, K. K., Thorsteinsson, K., Lebech, A.-M., & Fjordside, L. (2025). 18F-FDG PET/CT Findings in Glandular Tularemia. Diagnostics, 15(9), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091159