Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Adenocarcinomas in a 43-Year-Old Patient Following Infertility Treatment: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

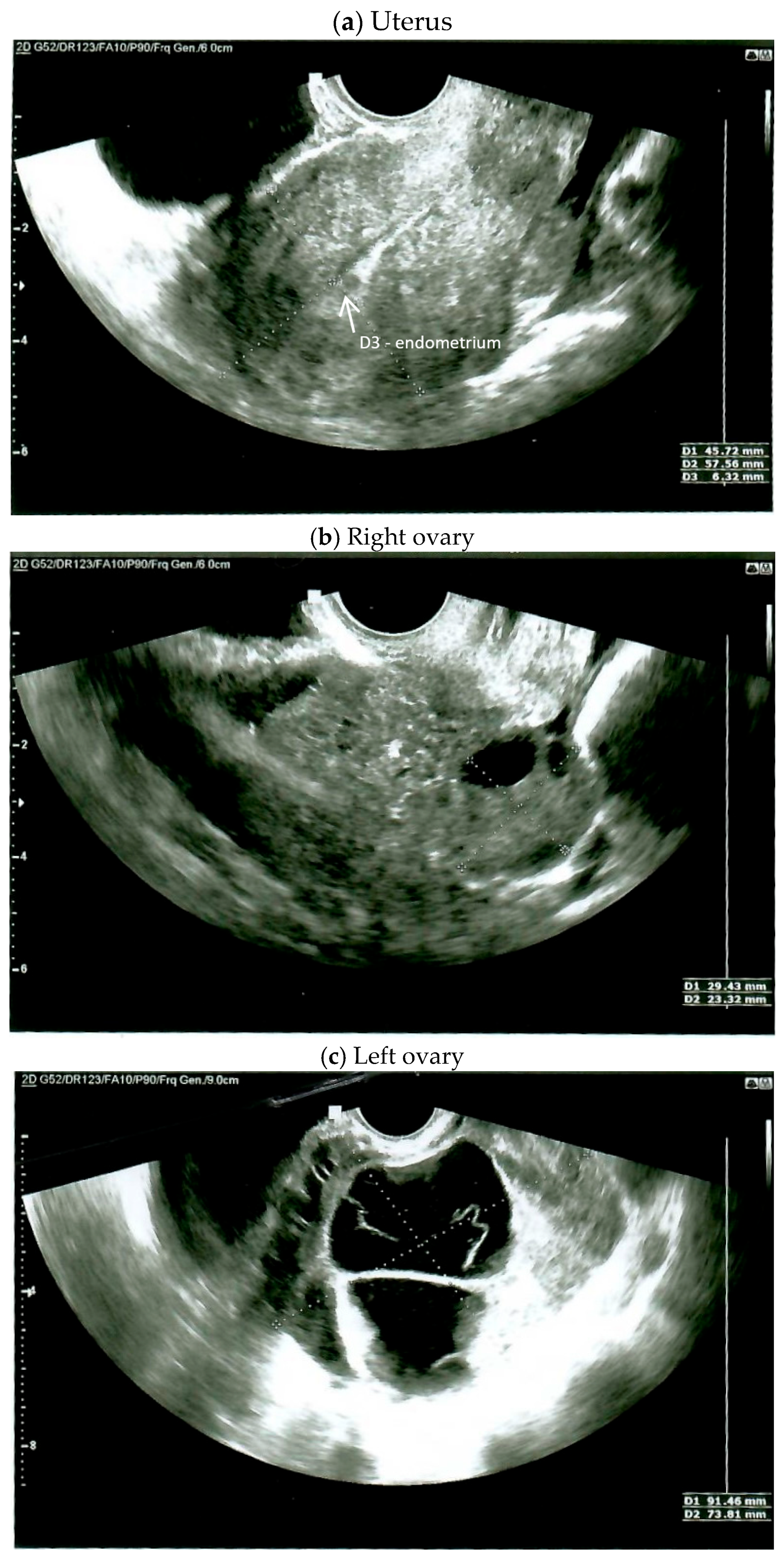

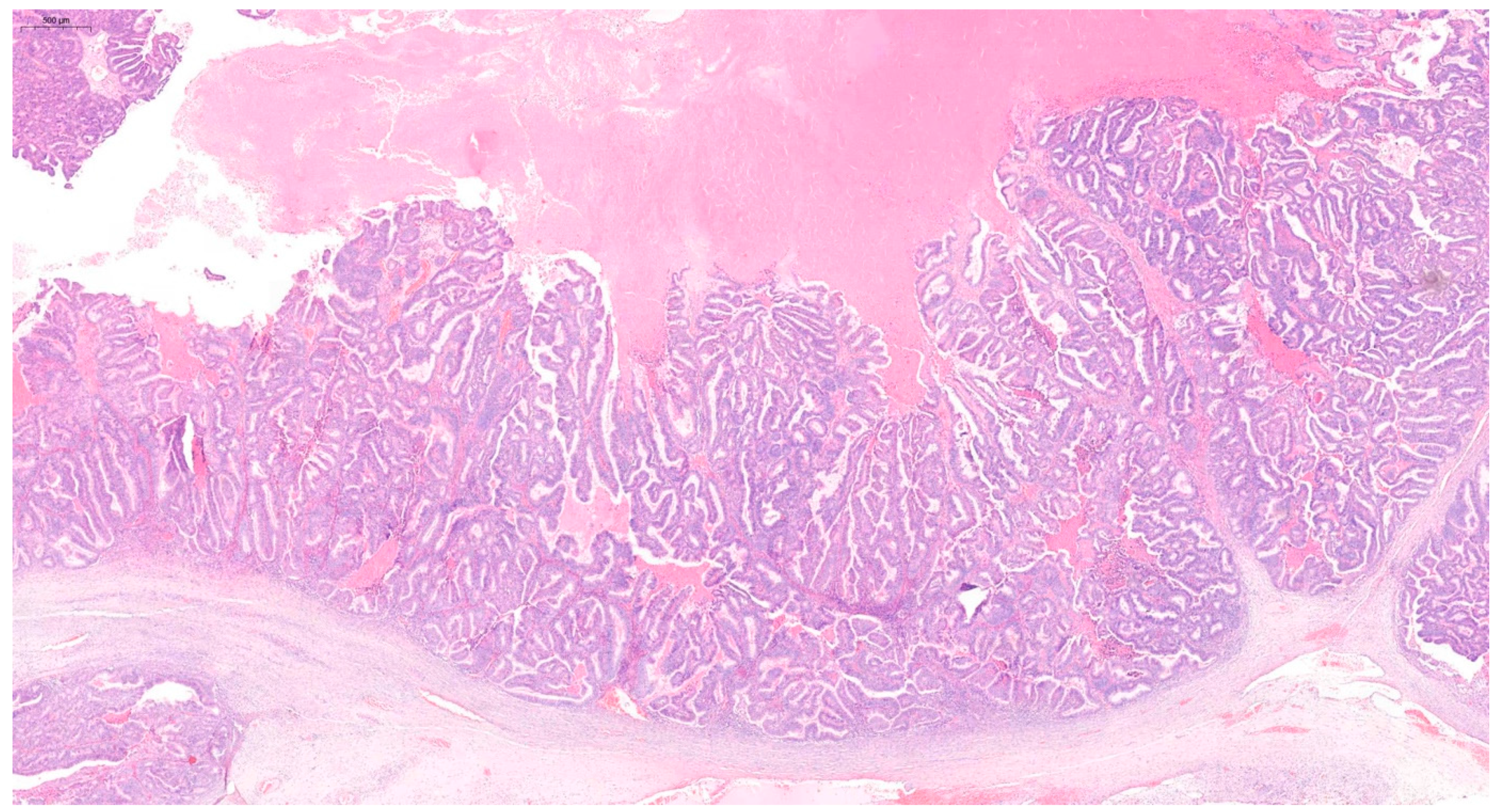

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schultheis, A.M.; Ng Ch De Filippo, M.R.; Piscuoglio, S. Massively Parallel Sequencing-Based Clonality Analysis of Synchronous Endometrioid Endometrial and Ovarian Carcinomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N. Synchronous tumours of the female genital tract. Histopathology 2010, 56, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaino, R.; Whitney, C.; Brady, M.F.; DeGeest, K.; Burger, R.A.; Buller, R.E. Simultaneously detected endometrial and ovarian carcinomas—A prospective clinicopathologic study of 74 cases: A gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 83, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Seong, S.J.; Bae, D.S.; Kim, J.H.; Suh, D.H.; Lee, K.H.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, T.S. Prognostic factors in women with synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębska-Szmich, S.; Czernek, U.; Krakowska, M.; Frąckowiak, M.; Zięba, A.; Czyżykowski, R.; Kulejewska, D.; Potemski, P. Synchronous primary ovarian and endometrial cancers: A series of cases and a review of literature. Prz. Menopauzalny 2014, 13, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.K.; Padma, R.; Foo, L.; Chia, Y.N.; Yam, P.; Chia, J.; Khoo-Tan, H.; Yap, S.P.; Yeo, R. Survival outcome of women with synchronous cancers of endometrium and ovary: A 10 year retrospective cohort study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 22, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moro, F.; Leombroni, M.; Pasciuto, T.; Trivellizzi, I.N.; Mascilini, F.; Ciccarone, F.; Zannoni, G.F.; Fanfani, F.; Scambia, G.; Testa, A.C. Synchronous primary cancers of endometrium and ovary vs endometrial cancer with ovarian metastasis: An observational study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 53, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Hua, K. Comparison and analysis of the clinicopathological features of SCEO and ECOM. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.K.; Zhang, H.T.; Sun, Y.C.; Wu, L.Y. Synchronous primary cancers of the endometrium and ovary: Review of 43 cases. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2008, 30, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bese, T.; Sal, V.; Kahramanoglu, I.; Tokgozoglu, N.; Demirkiran, F.; Turan, H.; Ilvan, S.; Arvas, M. Synchronous Primary Cancers of the Endometrium and Ovary with the Same Histopathologic Type Versus Endometrial Cancer with Ovarian Metastasis: A Single Institution Review of 72 Cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.; Park, S.Y.; Kang, S.; Lim, M.C.; Seo, S.S. How to manage synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer patients? BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dogan, A.; Schultheis, B.; Rezniczek, G.A.; Hilal, Z.; Cetin, C.; Häusler, G.; Tempfer, C.B. Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer in Young Women: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Anticancer. Res. 2017, 37, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Decavalas, G.; Adonakis, G.; Androutsopoulos, G.; Gkogkos, P.; Koumoundourou, D.; Ravazoula, P.; Kourounis, G. Synchronous primary endometrial and ovarian cancers: A case report. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2006, 27, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eifel, P.; Hendrickson, M.; Ross, J.; Ballon, S.; Martinez, A.; Kempson, R. Simultaneous presentation of carcinoma involving the ovary and the uterine corpus. Cancer 1982, 50, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias-Guiu, X.; Lagarda, H.; Catasus, L.; Bussaglia, E.; Gallardo, A.; Gras, E.; Prat, J. Clonality analysis in synchronous or metachronous tumors of the female genital tract. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2002, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.P.; Cook, L.S.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.-O.; Anderson, K.E.; Cai, H.; Cerhan, J.R.; Clendenen, T.V.; Felix, A.S.; Friedenreich, C.M.; et al. Infertility and incident endometrial cancer risk: A pooled analysis from the epidemiology of endometrial cancer consortium (E2C2). Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Sharif, H.; Olsen, J.H.; Kjaer, S.K. Risk of breast cancer and gynecologic cancers in a large population of nearly 50,000 infertile Danish women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brinton, L.A.; Westhoff, C.L.; Scoccia, B.; Lamb, E.J.; Althuis, M.D.; Mabie, J.E.; Moghissi, K.S. Causes of infertility as predictors of subsequent cancer risk. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworoger, S.S.; Fairfield, K.M.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.A.; Hankinson, S.E. Association of oral contraceptive use, other contraceptive methods, and infertility with ovarian cancer risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner-Geva, L.; Rabinovici, J.; Olmer, L.; Blumstein, T.; Mashiach, S.; Lunenfeld, B. Are infertility treatments a potential risk factor for cancer development? Perspective of 30 years of follow-up. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28, 809–814. [Google Scholar]

- Momenimovahed, Z.; Taheri, S.; Tiznobaik, A.; Salehiniya, H. Do the fertility drugs increase the risk of cancer? A review study. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pup, L.; Peccatori, F.A.; Levi-Setti, P.E.; Codacci-Pisanelli, G.; Patrizio, P. Risk of cancer after assisted reproduction: A review of the available evidences and guidance to fertility counselors. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 8042–8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroener, L.; Dumesic, D.; Al-Safi, Z. Use of fertility medications and cancer risk: A review and update. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskas, M.; Uzan, J.; Luton, D.; Rouzier, R.; Daraï, E. Prognostic factors of oncologic and reproductive outcomes in fertility-sparing management of endometrial atypical hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz, F.; Amant, F.; Fotopoulou, C.; Battista, M.J.; Wimberger, P.; Traut, A.; Fisseler-Eckhoff, A.; Harter, P.; Vandenput, I.; Sehouli, J.; et al. Synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancer—An international multicenter case-control study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Nguyen, V.T. Additional value of Doppler ultrasound to B-mode ultrasound in assessing for uterine intracavitary pathologies among perimenopausal and postmenopausal bleeding women: A multicentre prospective observational study in Vietnam. J. Ultrasound 2023, 26, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Nguyen, V.T. Endometrial thickness and uterine artery Doppler parameters as soft markers for prediction of endometrial cancer in postmenopausal bleeding women: A cross-sectional study at tertiary referral hospitals from Vietnam. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2022, 65, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia; No. 67, RCOG/BSGE Joint Guideline; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists/British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy Green-Top Guideline: London, UK, 2016.

- Gallos, I.D.; Shehmar, M.; Thangaratinam, S.; Papapostolou, T.K.; Coomarasamy, A.; Gupta, J.K. Oral progestogens vs levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, e541–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Seong, S.J.; Kim, J.W.; Jeon, S.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, I.H.; Lee, J.H.; Ju, W.; Song, E.S.; Park, H.; et al. Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia with a Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System: A Korean Gynecologic-Oncology Group Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 711–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Park, H.; Yoon, B.S.; Seong, S.J.; Kang, J.H.; Jun, H.S.; Park, C.T. The effectiveness of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia in Korean women. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 21, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Varma, R.; Soneja, H.; Bhatia, K.; Ganesan, R.; Rollason, T.; Clark, T.J.; Gupta, J.K. The effectiveness of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia: A long-term follow-up study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 139, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildemeersch, D.; Janssens, D.; Pylyser, K.; De Wever, N.; Verbeeck, G.; Dhont, M.; Tjalma, W. Management of patients with non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: Long-term follow-up. Maturitas 2007, 57, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbo, A.; Arnes, M.; Hancke, C.; Vereide, A.B.; Pettersen, I.; Larsen, K. Treatment results of endometrial hyperplasia after prospective D-score classification: A follow-up study comparing effect of LNG-IUD and oral progestins versus observation only. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 111, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbo, A.; Vereide, A.; Arnes, M.; Pettersen, I.; Straume, B. Levonorgestrel-impregnated intrauterine device as treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: A national multicentre randomised trial. BJOG 2014, 121, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaolino, P.; Cafasso, V.; Boccia, D.; Ascione, M.; Mercorio, A.; Viciglione, F.; Palumbo, M.; Serafino, P.; Buonfantino, C.; De Angelis, M.C.; et al. Fertility-Sparing Approach in Patients with Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer Grade 2 Stage IA (FIGO): A Qualitative Systematic Review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4070368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, J.-X.; Wu, M.; Lang, J.-H.; Huo, Z.; Shen, K. Fertility-preserving treatment in young women with well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma and severe atypical hyperplasia of endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilavarasi, C.R.; Jyothi, G.S.; Alva, N.K. Study of the Efficacy of Pipelle Biopsy Technique to diagnose Endometrial Diseases in Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. J. Midlife Health 2019, 10, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, P.; Barcia, S.; DiSciullo, A.; Warda, H. Improved adequacy of endometrial tissue sampled from postmenopausal women using the MyoSure Lite hysteroscopic tissue removal system versus conventional curettage. Int. J. Womens Health 2017, 9, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siristatidis, C.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Kanavidis, P.; Trivella, M.; Sotiraki, M.; Mavromatis, I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.T. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for IVF: Impact on ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer—A systematic review and meta- analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reigstad, M.M.; Larsen, I.K.; Myklebust, T.Å.; Robsahm, T.E.; Oldereid, N.B.; Omland, A.K.; Vangen, S.; Brinton, L.A.; Storeng, R. Cancer risk among parous women following assisted reproductive technology. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1952–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, A.S.; Harris, R.; Itnyre, J. Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: Collaborative analysis of 12 US case- control studies. II. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancers in white women. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 136, 1184–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinton, L.A.; Trabert, B.; Shalev, V.; Lunenfeld, E.; Sella, T.; Chodick, G. In vitro fertilization and risk of breast and gynecologic cancers: A retrospective cohort study within the Israeli Maccabi healthcare services. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanos, P.; Dimitriou, S.; Gullo, G.; Tanos, V. Biomolecular and Genetic Prognostic Factors That Can Facilitate Fertility-Sparing Treatment (FST) Decision Making in Early Stage Endometrial Cancer (ES-EC): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, L.; Manavella, D.D.; Gullo, G.; McNamara, B.; Santin, A.D.; Patrizio, P. Endometrial Cancer in Reproductive Age: Fertility-Sparing Approach and Reproductive Outcomes. Cancers 2022, 14, 5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivegna, E.; Maulard, A.; Pautier, P.; Chargari, C.; Gouy, S.; Morice, P. Fertility results and pregnancy outcomes after conservative treatment of cervical cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1195–1211.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglesio, M.S.; Wang, Y.K.; Maassen, M.; Horlings, H.M.; Bashashati, A.; Senz, J.; Mackenzie, R.; Grewal, D.S.; Li-Chang, H.; Karnezis, A.N.; et al. Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Carcinomas: Evidence of Clonality. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Girolimetti, G.; Perrone, A.M.; Procaccini, M.; Kurelac, I.; Ceccarelli, C.; De Biase, D.; Caprara, G.; Zamagni, C.; De Iaco, P.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA genotyping efficiently reveals clonality of synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Number of Cases | Research Time | Mean Age | Endometrial Cancer Characteristics | Ovarian Cancer Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological Type | Number of Cases | Histopathological Type | Number of Cases | ||||

| Song T et al. [4] | 123 | 1995–2010 | 50.4 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid | 100 23 | Endometrioid Serous Clear-cell Mucinous Mixed Others | 62 26 8 15 8 4 |

| Sylwia DębskaSzmich et al. [5] | 10 | 2008–2013 | 56 | Endometrioid | 10 | Endometrioid Papillary cystadenocarcinoma Mucinous adenocarcinoma Undifferentiated carcinoma | 7 1 1 1 |

| Yong Kuei Lim et al. [6] | 46 | 2000–2009 | 47.3 | Endometrioid | 46 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid | 34 12 |

| Moro F et al. [7] | 51 | 2010–2018 | 57.7 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid | 43 8 | Endometrioid High-grade serous carcinoma | 30 10 |

| Clear-cell carcinoma Mixed Tubal cancer Other | 3 3 2 3 | ||||||

| Wang T et al. [8] | 51 | 2009–2017 | 53.96 | Endometrioid | 51 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid | 33 18 |

| Ma SK et al. [9] | 43 | 2008 | 49 | Endometrioid | 43 | Endometrioid or a mixed tumor with endometrioid component Non-endometrioid | 30 13 |

| Bese T et al. [10] | 31 | 1997–2015 | 52.6 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid | 18 13 | ||

| Shin W et al. [11] | 28 | 2006–2018 | 50 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid (serous clear cell) | 25 3 2 1 | Endometrioid Non-endometrioid Serous Clear-cell Seromucinous Mucinous Carcinosarcoma | 17 11 5 2 2 1 1 |

| Dogat A et al. [12] | 1 | 2017 | 45 | Endometrioid | Endometrioid | ||

| Decavalas G, et al. [13] | 1 | 2006 | 49 | Endometrioid | Endometrioid | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gajewska, M.; Suchońska, B.; Blok, J.; Gajzlerska-Majewska, W.; Ludwin, A. Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Adenocarcinomas in a 43-Year-Old Patient Following Infertility Treatment: A Case Report. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060670

Gajewska M, Suchońska B, Blok J, Gajzlerska-Majewska W, Ludwin A. Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Adenocarcinomas in a 43-Year-Old Patient Following Infertility Treatment: A Case Report. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(6):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060670

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajewska, Małgorzata, Barbara Suchońska, Joanna Blok, Wanda Gajzlerska-Majewska, and Artur Ludwin. 2025. "Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Adenocarcinomas in a 43-Year-Old Patient Following Infertility Treatment: A Case Report" Diagnostics 15, no. 6: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060670

APA StyleGajewska, M., Suchońska, B., Blok, J., Gajzlerska-Majewska, W., & Ludwin, A. (2025). Synchronous Endometrial and Ovarian Adenocarcinomas in a 43-Year-Old Patient Following Infertility Treatment: A Case Report. Diagnostics, 15(6), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15060670