Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Forearm in a 20-Week Pregnant Woman: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am. Surg. 1952, 18, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.-H.; Chang, H.-C.; Pasupathy, S.; Khin, L.-W.; Tan, J.-L.; Low, C.-O. Necrotizing fasciitis: Clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. JBJS 2003, 85, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.J.C.; Anaya, D.A.; Dellinger, E.P. Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salati, S.A. Necrotizing fasciitis—A review. Pol. J. Surg. 2022, 94, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gon, G.; Leite, A.; Calvert, C.; Woodd, S.; Graham, W.J.; Filippi, V. The frequency of maternal morbidity: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 141, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang-Auger, G.; Chasse, M.; Quach, C.; Ayoub, A.; Auger, N. Necrotizing Fasciitis: Association with Pregnancy-related Risk Factors Early in Life. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2021, 94, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nahas, S.; McKirdy, A.; Imbuldeniya, A. Successful management of a 24-year-old pregnant woman with necrotising fasciitis of the forearm. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, L.W.; Blaakær, J.; Helmig, R.B. Group A streptococci infection. A systematic clinical review exemplified by cases from an obstetric department. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 215, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, M. Necrotising fasciitis and group A streptococcus toxic shock-like syndrome in pregnancy: Treatment with plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin. Int. J. Obstet. Anesthesia 1999, 8, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.; Medhi, R.; Das, A.; Ahmed, M.; Das, B. Necrotizing fasciitis—A rare complication following common obstetric operative procedures: Report of two cases. Int. J. Women’s Health 2015, 7, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chua, W.C.; Mazlan, M.Z.; Ali, S.; Omar, S.C.; Hassan, W.M.N.W.; Seevaunnantum, S.P.; Zaini, R.H.M.; Hassan, M.H.; Besari, A.M.; Rahman, Z.A.; et al. Post-partum streptococcal toxic shock syndrome associated with necrotizing fasciitis. IDCases 2017, 9, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.; Greenhouse, P.; Donders, F.; Engel, U.; Paavonen, J.; Mendling, W. Genital Tract GAS Infection ISIDOG Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, S.W.; Pederson, W.C.; Kozin, S.H.; Cohen, M.S. Green’s Operative Surgery, 6th ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bryant, A.E. Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.; Proctor, L.K.; Shinar, S.; Philippopoulos, E.; Yudin, M.H.; Murphy, K.E. Outcomes and management of pregnancy and puerperal group A streptococcal infections: A systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapinsky, S.E. Obstetric infections. Crit. Care Clin. 2013, 29, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, S.; Rivera-Hernandez, T.; Curren, B.F.; Harbison-Price, N.; De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Jespersen, M.G.; Davies, M.R.; Walker, M.J. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookstaver, P.B.; Bland, C.M.; Griffin, B.; Stover, K.R.; Eiland, L.S.; McLaughlin, M. A Review of Antibiotic Use in Pregnancy. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2015, 35, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steer, A.C.; Lamagn Ti Curtis, N.; Carapetis, J.R. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease. Drugs 2012, 72, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

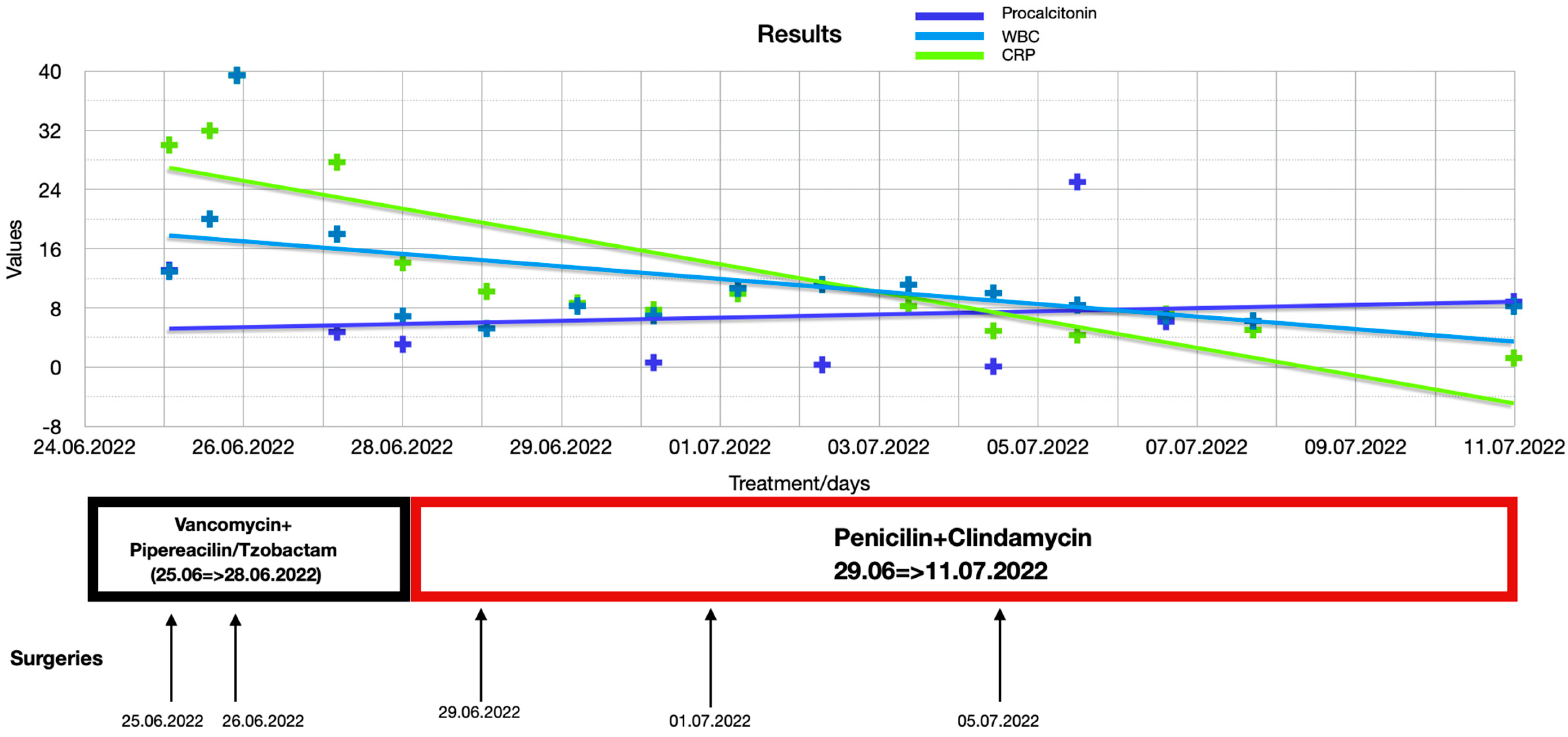

| Days | WBC (× 109/L) | CRP (mg/dL) | Procalcitonin (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25/06/2022 05:53 | 12.91 | 30.00 | 8.835 |

| 25/06/2022 17:526 | 20.02 | 31.94 | |

| 26/06/2022 01:12 | 39.42 | 39.42 | 6.151 |

| 27/06/2022 05:44 | 17.98 | 27.68 | 25.009 |

| 28/06/2022 00:29 | 6.87 | 14.11 | |

| 29/06/2022 00:23 | 5.23 | 10.22 | 13.090 |

| 30/06/2022 02:16 | 8.26 | 8.68 | |

| 30/06/2022 23:59 | 6.94 | 7.75 | 4.752 |

| 02/07/2022 00:01 | 10.66 | 9.92 | 3.082 |

| 03/07/2022 00:04 | 11.16 | 11.16 | |

| 04/07/2022 00:39 | 11.13 | 8.24 | |

| 05/07/2022 00:51 | 10.00 | 4.90 | 0.614 |

| 06/07/2022 00:48 | 8.40 | 4.33 | |

| 07/07/2022 02:05 | 6.90 | 7.18 | 0.320 |

| 08/07/2022 02:54 | 6.24 | 5.04 | |

| 11/07/2022 05:14 | 8.24 | 1.23 | 0.092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mironică, A.; Ioncioaia, B.; Janko, B.; Dindelegan, G.C.; Ilie-Ene, A.; Furcovici, L.-I.; Sarkadi, B.; Filip, C.I. Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Forearm in a 20-Week Pregnant Woman: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15040495

Mironică A, Ioncioaia B, Janko B, Dindelegan GC, Ilie-Ene A, Furcovici L-I, Sarkadi B, Filip CI. Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Forearm in a 20-Week Pregnant Woman: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(4):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15040495

Chicago/Turabian StyleMironică, Andreea, Bogdan Ioncioaia, Botond Janko, George Călin Dindelegan, Alexandru Ilie-Ene, Lucia-Ioana Furcovici, Balazs Sarkadi, and Claudiu Ioan Filip. 2025. "Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Forearm in a 20-Week Pregnant Woman: Case Report and Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 4: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15040495

APA StyleMironică, A., Ioncioaia, B., Janko, B., Dindelegan, G. C., Ilie-Ene, A., Furcovici, L.-I., Sarkadi, B., & Filip, C. I. (2025). Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Forearm in a 20-Week Pregnant Woman: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(4), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15040495