Integrated Anthropometric, Physiological and Biological Assessment of Elite Youth Football Players Using Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

- First, anthropometric parameters were assessed, including longitudinal, transversal, and sagittal body dimensions, as well as body weight and the Body Mass Index (BMI). These measurements were conducted following ISAK (International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry) recommendations and complementary Romanian reference protocols. They provided information on proportional growth, musculoskeletal loading, and potential risk factors for postural imbalance or injury.

- Second, physical parameters were evaluated through functional tests of muscular strength and spinal mobility. Specifically, handgrip strength (right and left) was measured with a digital dynamometer, lumbar strength with a back dynamometer, and spinal flexibility with a standardized flexometer. These parameters are critical in football, where repeated high-intensity actions (sprints, jumps, tackles) expose the musculoskeletal system to substantial stress. All physical tests were performed in duplicate, and the best value was retained for analysis. Reliability for handgrip and lumbar strength testing in adolescent athletes is high (ICC 0.86–0.94), and the flexometer method has established field validity, strengthening the reproducibility of the measurements.

- Third, biological parameters were determined through hematological, biochemical, and urinary analyses, performed in an accredited clinical laboratory. The hematological profile included hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Ht), and white blood cell count (WBC), reflecting oxygen transport capacity and immune status. The biochemical panel covered markers of metabolic control, liver and renal adaptation, and electrolyte balance, namely alanine aminotransferase (ALT/TGP), fasting glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), C-reactive protein (CRP), urea, creatinine (Cr), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg). Finally, urinary markers were assessed, including urine specific gravity (USG) for hydration balance, proteinuria (ProtU) for renal/muscle integrity, and hematuria (HemU) as a potential indicator of microtrauma or dehydration.

2.2. Anthropometric Evaluation

2.2.1. Physical Development Assessment

- •

- Height (stature) was measured with a stadiometer, subjects standing barefoot with their heads in the Frankfurt plane. As an indicator of longitudinal growth, stature directly influences balance and the loading of lower limb joints, with extreme values predisposing athletes to increased stress on the knees and ankles.

- •

- Arm span was determined using a rigid anthropometric rod, with arms fully extended laterally. This parameter serves as a marker of proportionality relative to height, where discrepancies may signal postural adaptations or shoulder asymmetry.

- •

- Biacromial diameter (shoulder breadth) was assessed with a large caliper placed between the acromial landmarks. This measurement reflects scapular stability, and imbalances with pelvic width may predispose players to disharmony between the upper and lower girdles.

- •

- Bitrochanteric diameter (Pelvic breadth) was measured between the trochanteric landmarks. As a determinant of hip–knee alignment, a wide pelvis may modify the Q-angle, thus increasing the risk of knee injuries.

- •

- Thoracic diameters were assessed both transversally (mid-axillary line) and sagittally (between the xiphoid appendix and thoracic vertebrae), in both inspiration and expiration. These chest dimensions are closely linked to respiratory efficiency and posture; a narrow or flattened chest can reduce ventilatory capacity and promote postural imbalance.

2.2.2. Nutritional Status Assessment

2.3. Physical Evaluation

2.3.1. Handgrip Strength (Right/Left)

- •

- Position: standing upright, arms alongside the body, elbow extended.

- •

- Adjustment: handle adapted to hand size to allow a 90° angle at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger.

- •

- Output: maximal voluntary contraction, reported in kilograms (kg) (Table 5).

2.3.2. Lumbar Strength

- •

- Position: standing on the platform with feet shoulder-width apart.

- •

- Initial posture: trunk inclined forward at ~30°, arms extended holding the handle.

- •

- Execution: gradual extension of the trunk while maintaining knees fully extended.

- •

- Output: maximal force (kg) (Table 6).

2.3.3. Spinal Mobility

- •

- Position: standing on a 50 cm-high platform, feet together, arms extended.

- •

- Execution: slow forward flexion without knee bending, pushing the cursor of the flexometer as far as possible.

- •

- Output: maximal displacement (cm) (Table 7).

2.4. Biological Evaluation

2.4.1. Hematological and Biochemical Parameters

2.4.2. Urinalysis Parameters

2.5. Statistical and Machine Learning Methods

- •

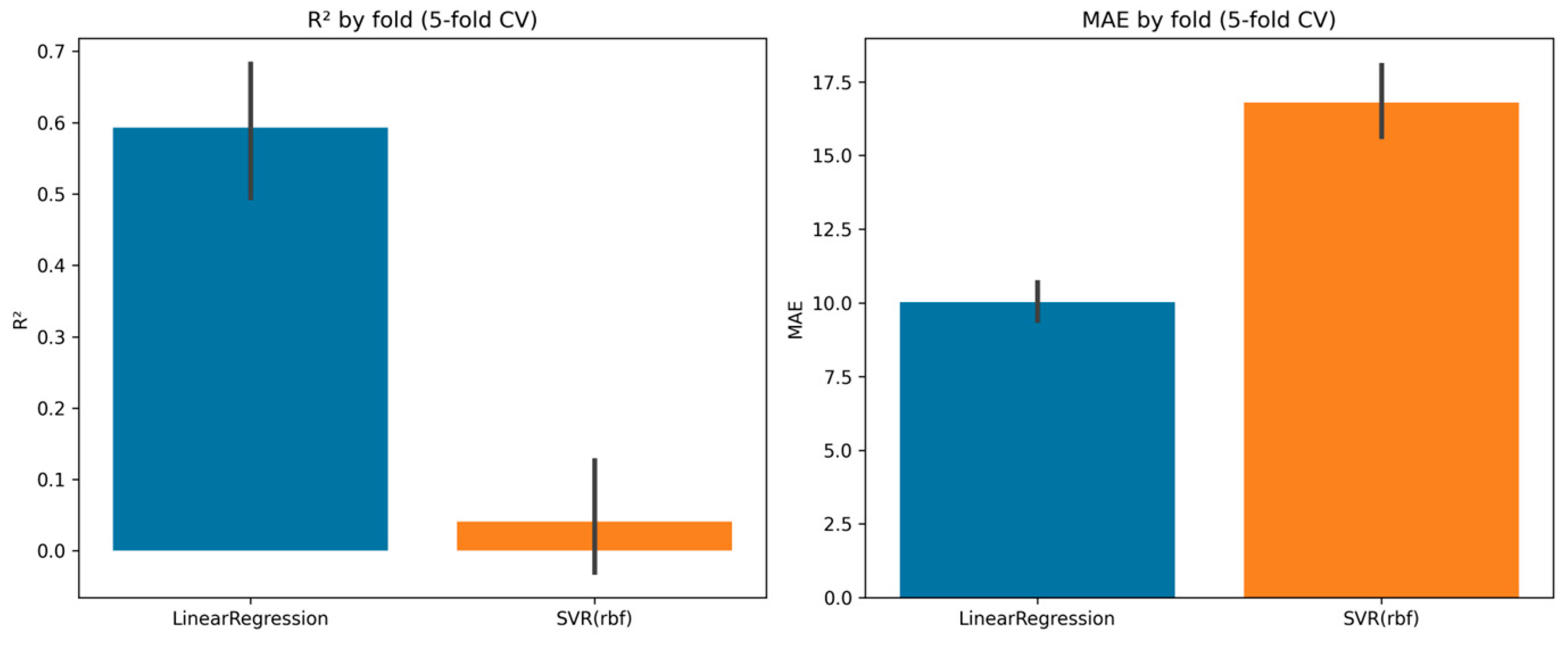

- Linear regression was selected as an interpretable baseline model suitable for medium-sized datasets and continuous outcomes. SVR (RBF kernel) was included to explore potential non-linear relationships not captured by linear models.

- •

- Model performance was evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation rather than a fixed train-test split, improving robustness and reducing overfitting risks.

- •

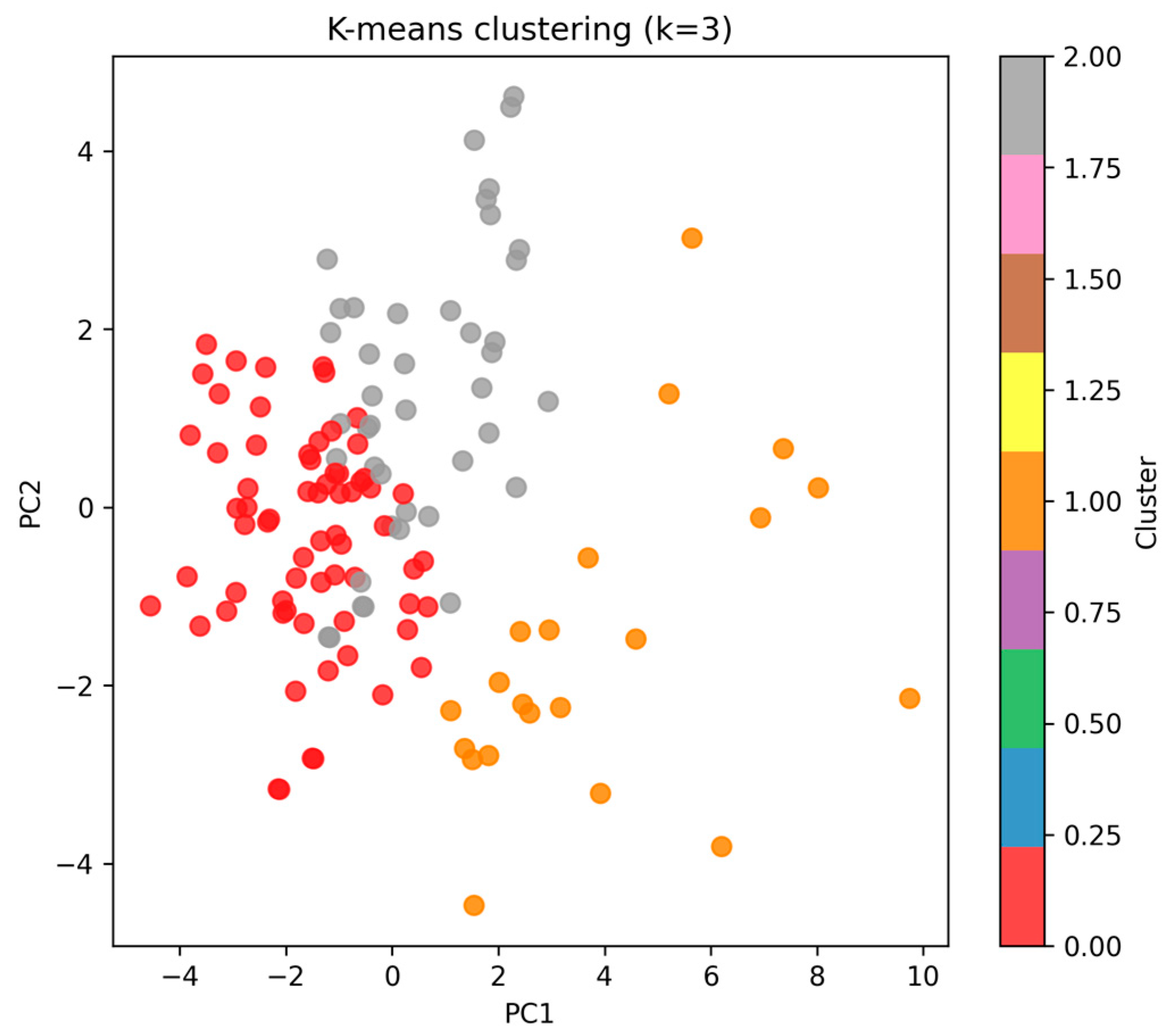

- K-means clustering was used to identify hidden adaptation profiles. The optimal number of clusters (k = 3) was determined through the elbow method and silhouette scores, indicating best separation and compactness at k = 3.

3. Results

3.1. Anthropometric Results

- •

- Anteroposterior and transverse diameters;

- •

- Body weight (r = 0.47, p < 0.001) and BMI (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), suggesting that older players exhibited more developed somatic features;

- •

- Height and arm span were strongly correlated (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), confirming proportional body development, and both were strongly associated with trunk and chest diameters;

- •

- Lot 1 (older group): age correlated significantly with chest diameter (r = 0.46, p = 0.019) and BMI (r = 0.57, p = 0.003). An arm span–height correlation remained strong (r = 0.73, p < 0.001).

- •

- Lot 2 (intermediate group): stronger structural associations were evident, with height correlating with arm span (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), shoulder and chest diameters (r > 0.70, p < 0.001), and body weight (r = 0.68, p < 0.001).

- •

- Lot 3 (younger group): similar but slightly weaker patterns, with arm span–height correlation (r = 0.67, p < 0.001) and consistent associations between trunk diameters and body weight (r = 0.43–0.61, p < 0.01).

3.1.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.1.2. MANOVA Between Lots

3.2. Physical Results

- •

- Lot 1: 5.55 ± 6.29% (median = 4.25%).

- •

- Lot 2: 5.63 ± 5.94% (median = 3.87%).

- •

- Lot 3: 5.21 ± 3.51% (median = 4.57%).

3.3. Biological Results

3.4. Machine Learning Analysis

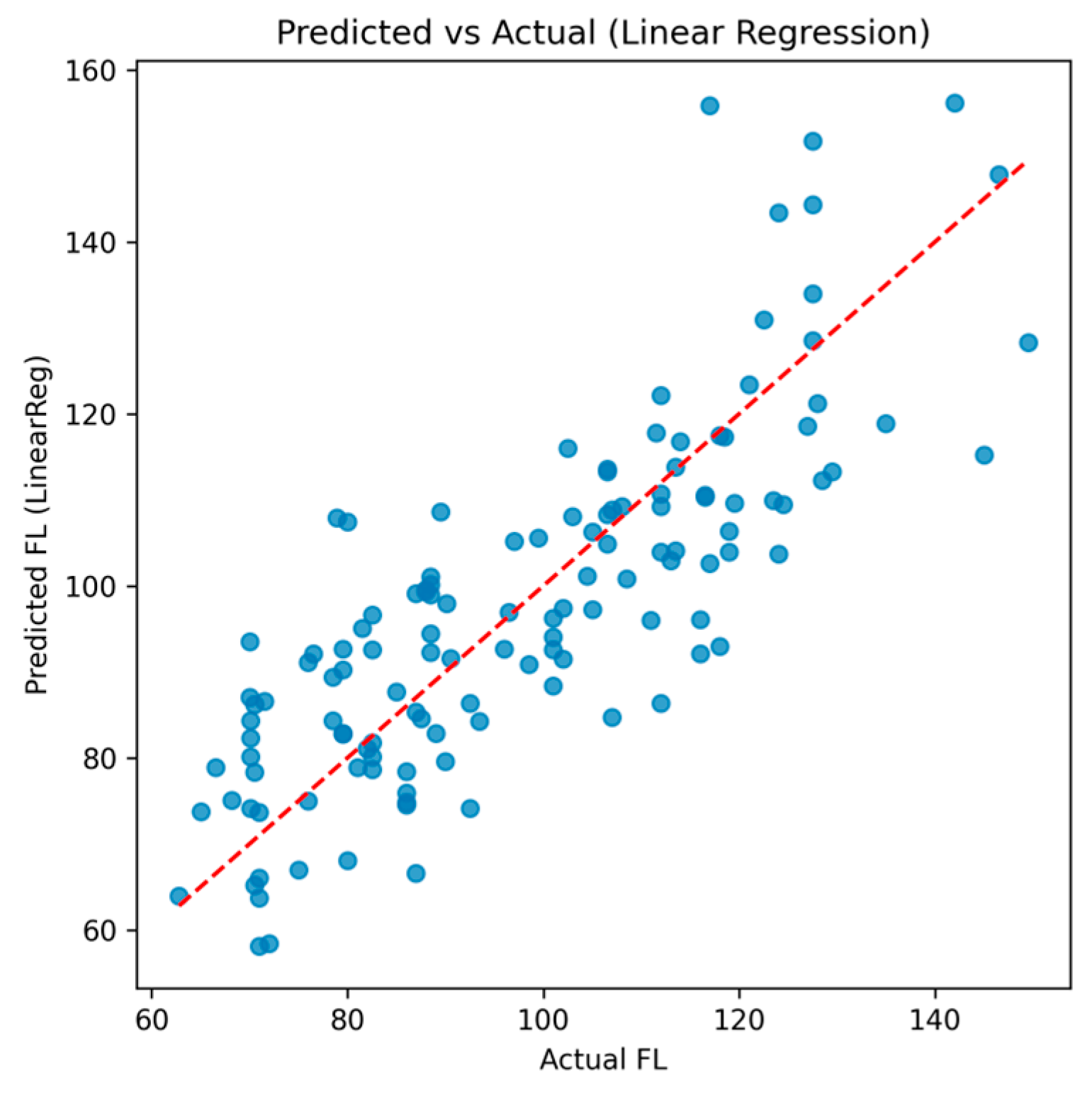

3.4.1. Linear Regression

3.4.2. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

3.4.3. Unsupervised Clustering

- •

- Cluster 0 (n = 67, ~52% of cohort).

- •

- Cluster 1 (n = 21, ~16%).

- •

- Cluster 2 (n = 42, ~32%).

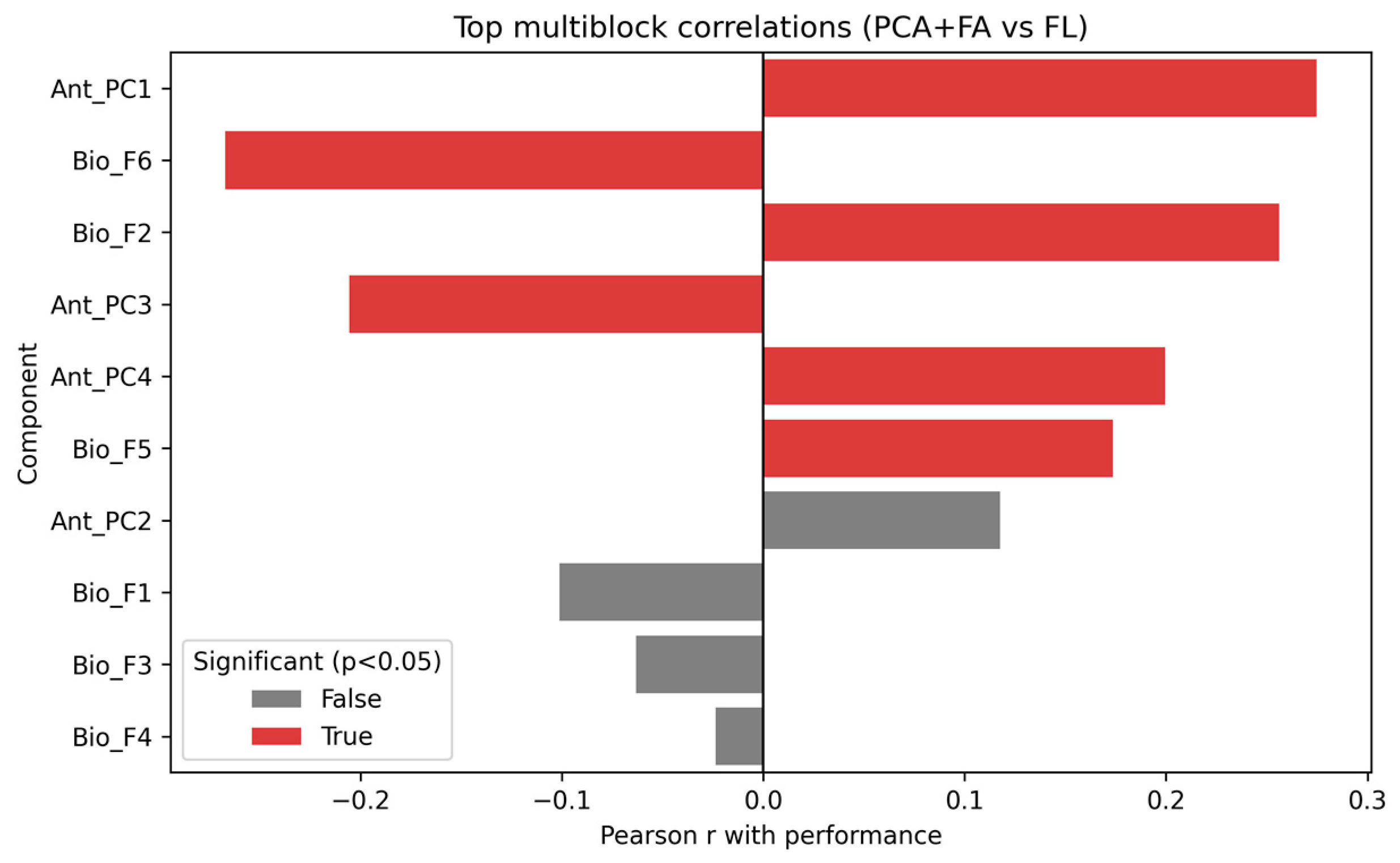

3.4.4. Multiblock Correlation Analysis

- •

- Ant_PC1 (r = 0.28, p = 0.002), reflecting general anthropometric variance.

- •

- Bio_F6 (r = −0.27, p = 0.002) and Bio_F2 (r = 0.26, p = 0.003), capturing relevant biological domains.

- •

- Ant_PC3 (r = −0.21, p = 0.019) and Ant_PC4 (r = 0.20, p = 0.023).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Integrated Interpretation

4.2. Practical Implications for Performance and Injury Prevention

- •

- Structure (Anthropometry): track proportionality indices (e.g., arm span–height; shoulder–pelvis balance) and use maturity-adjusted references to avoid conflating growth with performance.

- •

- Function (Physical): monitor symmetry longitudinally; although group AI is acceptable (~5%), individual outliers (up to ~30%) warrant corrective microcycles (unilateral strength, motor control, landing mechanics). Lot and age effects on fl justify age-/maturity-aware benchmarking.

- •

- State (Biology): use composite indices (hematology, hepatic–metabolic, lipid/renal, electrolytes, inflammation) as a concise dashboard to tailor nutrition, hydration, and recovery—especially when lipid/renal composites deviate (e.g., >+1 SD) under rising loads.

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

4.4. Overall Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Asymmetry Index |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of Covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| Ant_PCk | Anthropometric Principal Component k |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| Bio_Fk | Biological Factor k |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CMS | Standard protocol within this study |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| Cr | Creatinine |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| FA | Factor Analysis |

| FFP | (Lower-limb) Functional Power |

| FFPD/FFPS | FFP Dominant/FFP Non-dominant |

| FL | (Composite) Physical Performance Index |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HemU | Hematuria |

| Ht | Hematocrit |

| ISAK | International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MANOVA | Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ProtU | Proteinuria |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RPE | Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| USG | Urine Specific Gravity |

| WBCs | White Blood Cells |

References

- Jayanthi, N.; Pinkham, C.; Dugas, L.; Patrick, B.; Labella, C. Sports specialization in young athletes: Evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health 2013, 5, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mathias, H.; Tynke, T.; Geir, J. From childhood to senior professional football: A multi-level approach to elite youth football players’ engagement in football-specific activities. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guan, Y. International youth football research developments: A CiteSpace-based bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weishorn, J.; Jaber, A.; Zietzschmann, S.; Spielmann, J.; Renkawitz, T.; Bangert, Y. Injury Patterns and Incidence in an Elite Youth Football Academy-A Prospective Cohort Study of 138 Male Athletes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- James, J. Overuse Injuries in Young Athletes: Cause and Prevention. Strength Cond. J. 2008, 30, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Orozco, M.F.; Posada-Falomir, M.; Quiñónez-Gastélum, C.M.; Plascencia-Aguilera, L.P.; Arana-Nuño, J.R.; Badillo-Camacho, N.; Márquez-Sandoval, F.; Holway, F.E.; Vizmanos-Lamotte, B. Anthropometric and Body Composition Profile of Young Professional Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gundersen, H.; Grendstad, H.; Rygh, C.B.; Hafstad, A.; Vestbøstad, M.; Algerøy, E.; Smith, O.R.F.; Joensen, M.; Kristoffersen, M. The Role of Growth and Maturation in the Physical Development of Youth Male Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nechita, L.C.; Tutunaru, D.; Nechita, A.; Voipan, A.E.; Voipan, D.; Tupu, A.E.; Musat, C.L. AI and Smart Devices in Cardio-Oncology: Advancements in Cardiotoxicity Prediction and Cardiovascular Monitoring. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nechita, L.C.; Tupu, A.E.; Nechita, A.; Voipan, D.; Voipan, A.E.; Tutunaru, D.; Musat, C.L. The Impact of Quality of Life on Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Clinical, Demographic, and AI-Assisted Statistical Investigation. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reis, F.J.J.; Alaiti, R.K.; Vallio, C.S.; Hespanhol, L. Artificial intelligence and Machine Learning approaches in sports: Concepts, applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2024, 28, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liron, P.; Thomas, P.; Ibrahim, A.; Matthew, H.; Sarah, W.; Soong, T.; Ahmad, T.; Joshua, P.; Lu, M.; Faisal, M.; et al. Non-Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Medicine: Advancements and Applications in Supervised and Unsupervised Machine Learning. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 38, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: The Impact of Machine Learning on Predictive Analytics in Healthcare. Innov. Comput. Sci. J. 2023, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grivas, G.V.; Safari, K. Artificial Intelligence in Endurance Sports: Metabolic, Recovery, and Nutritional Perspectives. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, P.; Bayrakdar, A.; Meriçelli, M.; İncetaş, M.O.; Panoutsakopoulos, V.; Kollias, I.A.; Yildiz, Y.A.; Akbaş, D.; Satılmış, N.; Kilincarslan, G.; et al. The Use of Developing Technology in Sports; Özgür Yayın-Dağıtım Co. Ltd.: Istanbul, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, S.; Grigoletto, A.; Mauro, M. Anthropometric, body composition and physical performance of elite young Italian football players and differences between selected and unselected talents. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Danail, I. Comparative analysis of body composition in youth elite football players: Insights from professional academies. Tanjungpura J. Coach. Res. 2025, 3, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, F.Q. Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutr. Today 2015, 50, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jones, C.M.; Griffiths, P.C.; Mellalieu, S.D. Training Load and Fatigue Marker Associations with Injury and Illness: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 943–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Vermund, S.H. Advantages and Limitations of the Body Mass Index (BMI) to Assess Adult Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ji, W.; Shi, Y.; Liu, W.; Ji, W. Sports injuries in elite football players: Classification, prevention, and treatment strategies update. Front. Sports Act Living 2025, 7, 1643789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carlos, M.; Jorge, G.-U.; Antonio, H.-M.; Javier, S.-S.; Leonor, G.; Luis, F.J. Relationship between Repeated Sprint Ability, Countermovement Jump and Thermography in Elite Football Players. Sensors 2023, 23, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, D.; Nielsen, T.S.; Olsson, K.; Christensson, T.; Bradley, P.S.; Fatouros, I.G.; Krustrup, P.; Nordsborg, N.B.; Mohr, M. Skeletal muscle and performance adaptations to high-intensity training in elite male soccer players: Speed endurance runs versus small-sided game training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anđelković, M.; Baralić, I.; Đorđević, B.; Stevuljević, J.K.; Radivojević, N.; Dikić, N.; Škodrić, S.R.; Stojković, M. Hematological and Biochemical Parameters in Elite Soccer Players During A Competitive Half Season. J. Med. Biochem. 2015, 34, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leckey, C.; van Dyk, N.; Doherty, C.; Lawlor, A.; Delahunt, E. Machine learning approaches to injury risk prediction in sport: A scoping review with evidence synthesis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachelot, G.; Lamaziere, A.; Czernichow, S.; Faure, C.; Racine, C.; Levy, R.; Dupont, C. Nutrition and Fertility (ALIFERT) Group. Machine learning approach to assess the association between anthropometric, metabolic, and nutritional status and semen parameters. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 26, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuni, Y.; Esti, Y.; Ervin, Y. Analysis of the Application of Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification of Toddler Nutritional Status Based on Anthropometric Data. Indones. J. Electron. Electromed. Eng. Med. Inform. 2025, 7, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, H.H.; Albahra, S.; Robertson, S.; Tran, N.K.; Hu, B. Common statistical concepts in the supervised Machine Learning arena. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1130229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagip, L.; Artan, K.; Astrit, I.; Georgi, G. Differences in anthropometric characteristics of youth in football between elite and non-elite players. Phys. Educ. Theory Methodol. 2023, 23, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, J.; Brefin, S.L.; Nigg, C.R.; Koschnick, D.; Paul, C.; Ketelhut, S. Load and Recovery Monitoring in Top-Level Youth Soccer Players: Exploring the Associations of a Web Application-Based Score with Recognized Load Measures. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2025, 25, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Declan, O.R.; Niamh, W.; Siobhán, M. The effects of GPS metrics, training and competition load on recovery in elite male Gaelic Football Players. J. Aust. Strength Cond. 2024, 31, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44, S139–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aixa-Requena, S.; Gil-Galve, A.; Legaz-Arrese, A.; Hernández-González, V.; Reverter-Masia, J. Influence of Biological Maturation on the Career Trajectory of Football Players: Does It Predict Elite Success? J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANTHROPOMETRIC VARIABLES | ||||

| Age (years) | 17.28 | 2.04 | 16.00 | 27.00 |

| Height (cm) | 178.58 | 6.65 | 155.50 | 195.00 |

| Arm span (cm) | 179.22 | 6.70 | 164.00 | 195.00 |

| Biacromial diameter (cm) | 41.51 | 1.87 | 37.00 | 47.00 |

| Thoracic transverse diameter (cm) | 32.64 | 2.21 | 29.00 | 44.00 |

| Thoracic sagittal diameter (cm) | 27.56 | 2.02 | 21.00 | 33.00 |

| Anteroposterior diameter (cm) | 19.95 | 1.53 | 16.00 | 25.00 |

| Body mass (kg) | 69.12 | 9.16 | 49.00 | 98.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.58 | 2.30 | 16.67 | 27.65 |

| PHYSICAL PERFORMANCE VARIABLES | ||||

| FFPD—Dominant limb power (cm) | 38.44 | 6.25 | 23.10 | 62.30 |

| FFPS—Non-dominant limb power (cm) | 37.49 | 6.44 | 22.00 | 54.60 |

| FL—Performance index | 99.46 | 20.98 | 62.80 | 149.50 |

| BIOLOGICAL VARIABLES | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.14 | 0.86 | 12.10 | 16.90 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.64 | 2.47 | 35.80 | 48.50 |

| Leukocytes (×109/L) | 6.79 | 1.52 | 4.21 | 13.60 |

| ALT/TGP (U/L) | 17.35 | 5.52 | 9.00 | 35.00 |

| AST/TGO (U/L) | 26.01 | 7.49 | 15.00 | 65.00 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 87.17 | 5.76 | 69.00 | 99.00 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 51.75 | 9.82 | 32.00 | 74.00 |

| ESR/VSH (mm/h) | 5.59 | 2.22 | 3.00 | 20.00 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 4.80 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 33.86 | 8.43 | 16.00 | 53.00 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 1.22 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.68 | 0.39 | 7.90 | 10.60 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 1.91 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 2.90 |

| Urine specific gravity (g/L) | 1023.73 | 5.00 | 1006.00 | 1031.00 |

| Parameter | Women | Men | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (stature) | 155–175 cm | 165–185 cm | Outliers increase joint stress |

| Arm span | ≈height ± 3–5 cm | ≈height ± 3–5 cm | Disproportion → postural risk |

| Biacromial diameter | 36–38 cm | 40–44 cm | Shoulder–pelvis balance |

| Bitrochanteric diameter | 28–32 cm | 26–30 cm | Hip–knee mechanics |

| Thoracic transversal diameter | 24–28 cm | 28–32 cm | Breathing, posture |

| Thoracic sagittal diameter | 16–20 cm | 18–22 cm | Postural stability |

| Parameter | Description | Measurement Protocol | Relevance for Football Players/Injury Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight | Total body mass, reflecting muscular and fat tissue | Measured with calibrated scale, in the morning, barefoot, minimal clothing | Overweight ↑ stress on lower limb joints; underweight → insufficient muscle mass and reduced power |

| BMI | Weight-to-height ratio (kg/m2) | Calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2) | High BMI → potential obesity, ↑ injury risk; Low BMI → reduced energy reserves, fatigue |

| Parameter | Normal Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight | ≈height (cm)–100 ± 10% | Adjusted for sex and somatotype |

| BMI | 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | Should be interpreted with caution in athletes due to high muscle mass |

| Sex | Normal Range (kg) | Relevance for Football Players |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 40–60 | Marker of global strength; low values → reduced stability, fatigue risk |

| Female | 20–35 | Same role, lower absolute thresholds |

| Sex | Normal Range (kg) | Relevance for Football Players |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 120–180 | Essential for trunk stabilization; low values → predisposition to low back pain |

| Female | 70–120 | Lower absolute force, but relative to body weight, is critical for injury prevention |

| Sex | Normal Range (cm) | Relevance for Football Players |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 9–13 | Hypomobility → rigidity, higher risk of contractures; hypermobility → instability, entorses |

| Female | 13–15 | Better flexibility; extreme values must be interpreted cautiously |

| Parameter | Physiological Role | Relevance for Football Players/Injury Prevention | Reference Values (16–35 yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Oxygen transport | Low values → fatigue, ↓ aerobic capacity, ↑ muscle injury risk | M: 13–18 g/dL; F: 12–16 g/dL |

| Hematocrit (Ht) | Proportion of red cells | Low → hypoxia; High → blood viscosity ↑ thrombosis risk | M: 40–52%; F: 36–46% |

| Leukocytes (WBC) | Immune response | Elevated → infection/inflammation; ↓ recovery delays | 4000–10,000/µL |

| ALT (TGP), AST (TGO) | Hepatic and muscle enzymes | ↑ values → muscle microdamage or liver overload | <40 U/L |

| Fasting glucose | Energy supply | Low → hypoglycemia, cramps; High → poor metabolic control | 70–100 mg/dL |

| HDL cholesterol | Cardiovascular health | Low → poor oxygenation and recovery | M: >40 mg/dL; F: >50 mg/dL |

| LDL cholesterol | Lipid transport | High → cardiovascular stress | <130 mg/dL (optimal <100) |

| ESR (VSH) | Chronic inflammation | ↑ → slow tissue recovery, tendinopathies | M: 2–15 mm/h; F: 2–20 mm/h |

| CRP | Acute inflammation | ↑ → muscle microtrauma, overload | <5 mg/L |

| Urea | Protein metabolism | ↑ → catabolism, muscle fatigue | 15–45 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | Renal function, muscle mass | ↑ → dehydration, muscle overload | M: 0.6–1.3 mg/dL; F: 0.5–1.1 mg/dL |

| Calcium | Muscle contraction, bone health | Deficit → cramps, fractures | 8.5–10.2 mg/dL |

| Magnesium | Neuromuscular relaxation | Deficit → spasms, cramps | 1.6–2.6 mg/dL |

| Parameter | Description | Measurement Protocol | Relevance for Football Players/Injury Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinuria | Marker of renal/muscle integrity | Presence → microtrauma or renal stress | Absent/<150 mg/24 h |

| Hematuria | Red blood cells in urine | Indicates trauma, dehydration, or extreme effort | Absent/0–2 RBC per field |

| Specific gravity | Hydration balance | High → dehydration; Low → overhydration | 1.005–1.030 |

| Domain | Classical Statistics | Multivariate/ML Methods | Aim of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Descriptive statistics; Pearson correlations; ANOVA/ANCOVA (lot comparison, covariates: age, BMI); MANOVA (multivariate differences) | PCA (dimensionality reduction); Multiblock correlations (PCA scores vs. performance); K-means clustering (body proportionality profiles) | Characterize body proportions, test group differences, identify latent dimensions, link structure with performance. |

| Physical | Paired t-test (right–left comparison); ANOVA/ANCOVA (lot comparison, covariates: age, BMI); Asymmetry indices | Regression models (linear, SVR); K-fold cross-validation; K-means clustering | Evaluate muscular strength and flexibility, detect asymmetries, model performance predictors, and validate models. |

| Biological | Descriptive statistics with reference intervals; ANOVA/ANCOVA (lot comparison, covariates: age, BMI) | Factor Analysis (latent domains); Composite indices (inflammation, lipid, renal, hematology); Multiblock correlations (FA factors vs. performance) | Assess physiological adaptation, extract latent biological domains, build integrative indices, and link them to performance. |

| Fold | R2 (LinearReg) | MAE (LinearReg) | R2 (SVR, rbf) | MAE (SVR, rbf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.753 | 9.69 | 0.176 | 17.21 |

| 2 | 0.699 | 9.81 | −0.037 | 19.25 |

| 3 | 0.553 | 9.00 | 0.105 | 15.38 |

| 4 | 0.509 | 10.31 | −0.001 | 15.38 |

| 5 | 0.452 | 11.28 | −0.038 | 16.72 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.593 ± 0.114 | 10.02 ± 0.75 | 0.041 ± 0.085 | 16.79 ± 1.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nechita, L.C.; Gurau, T.V.; Musat, C.L.; Țupu, A.E.; Gurau, G.; Voinescu, D.C.; Nechita, A. Integrated Anthropometric, Physiological and Biological Assessment of Elite Youth Football Players Using Machine Learning. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243238

Nechita LC, Gurau TV, Musat CL, Țupu AE, Gurau G, Voinescu DC, Nechita A. Integrated Anthropometric, Physiological and Biological Assessment of Elite Youth Football Players Using Machine Learning. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243238

Chicago/Turabian StyleNechita, Luiza Camelia, Tudor Vladimir Gurau, Carmina Liana Musat, Ancuța Elena Țupu, Gabriela Gurau, Doina Carina Voinescu, and Aurel Nechita. 2025. "Integrated Anthropometric, Physiological and Biological Assessment of Elite Youth Football Players Using Machine Learning" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243238

APA StyleNechita, L. C., Gurau, T. V., Musat, C. L., Țupu, A. E., Gurau, G., Voinescu, D. C., & Nechita, A. (2025). Integrated Anthropometric, Physiological and Biological Assessment of Elite Youth Football Players Using Machine Learning. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243238