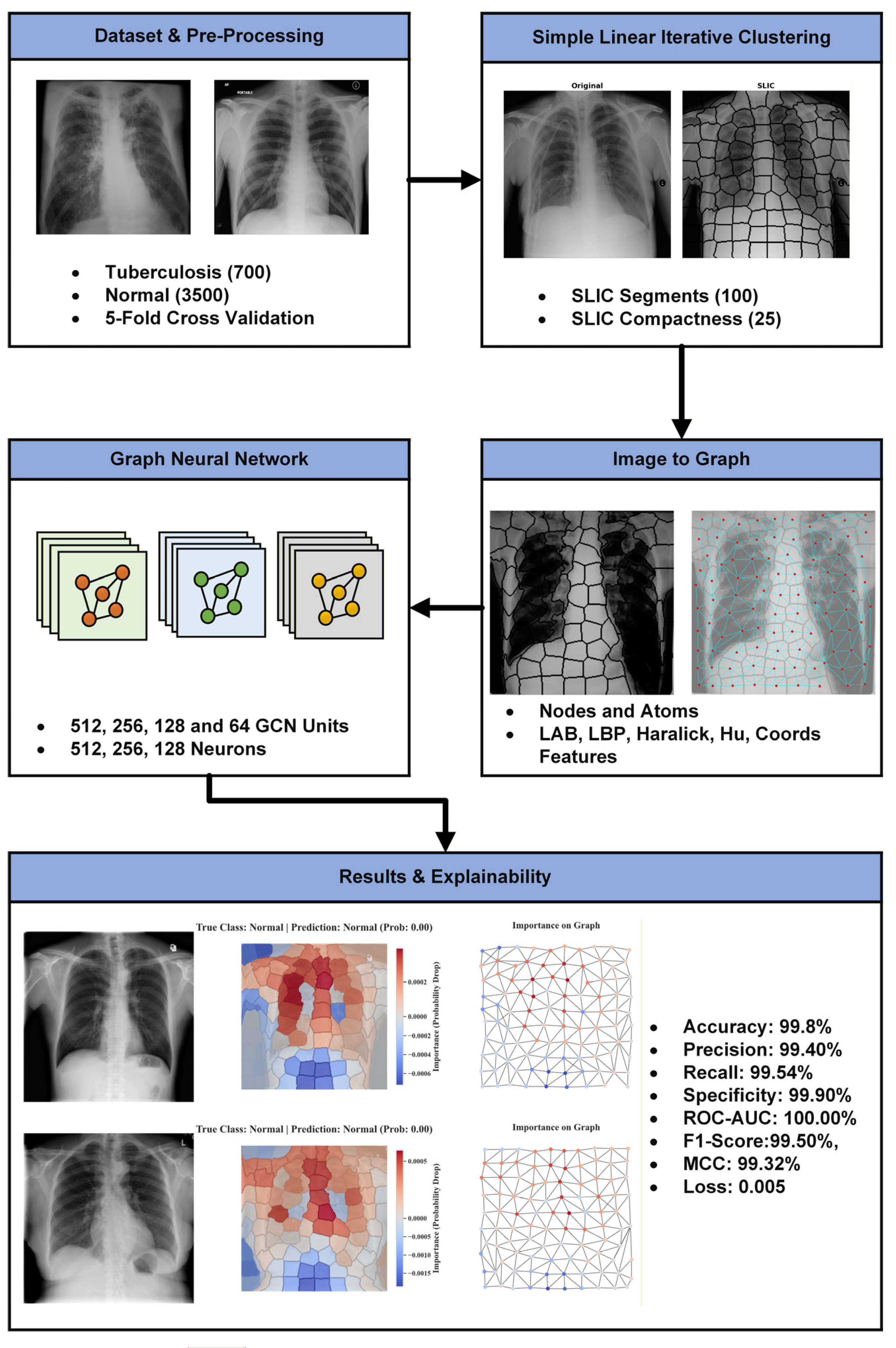

SPX-GNN: An Explainable Graph Neural Network for Harnessing Long-Range Dependencies in Tuberculosis Classifications in Chest X-Ray Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1-

- Enriched Structural Graph Representation: A novel method is presented that converts medical images into a structural graph. Each superpixel node is transformed into a holistic feature vector encoding complementary diagnostic clues: colour and intensity variations in CIELAB space, texture pattern distortions using LBP and Haralick features, and shape anomalies using orientation-independent Hu moments. This deliberate fusion renders each node a richer, more interpretable entity than raw pixels.

- 2-

- Global Contextual Learning: SPX-GNN performs higher-level reasoning by learning relational patterns between these rich node representations. The model situates local findings within a broader context, examining the relationship between specific attribute anomalies and suspicious findings in other areas of the image.

- 3-

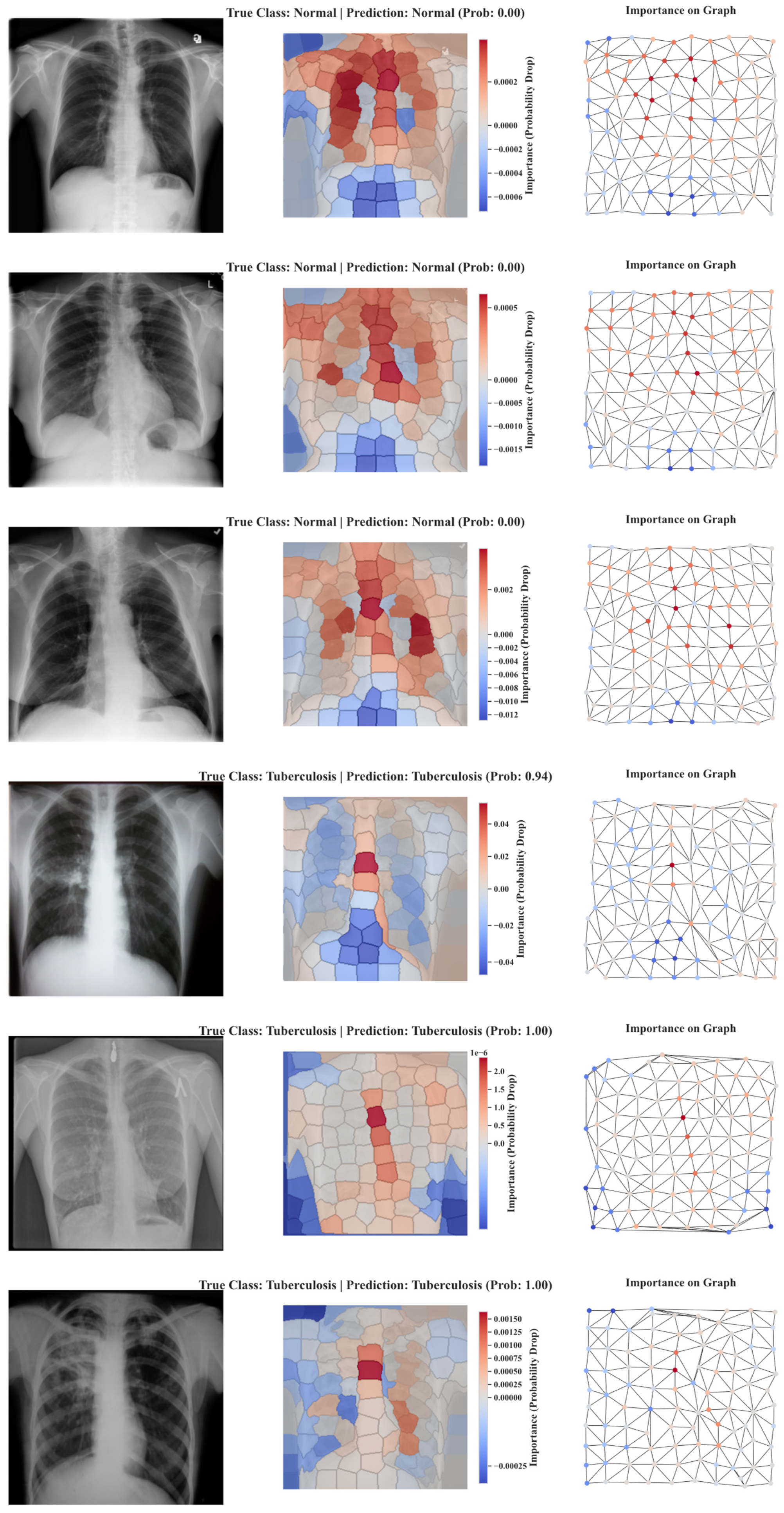

- Integrated Explainability: The framework includes an explainability module that generates node-level importance scores. This enhances clinical reliability by transforming the GNN’s decision-making process into intuitive importance maps, highlighting the specific anatomical regions contributing most significantly to the final diagnosis for concrete clinical decision support.

- 4-

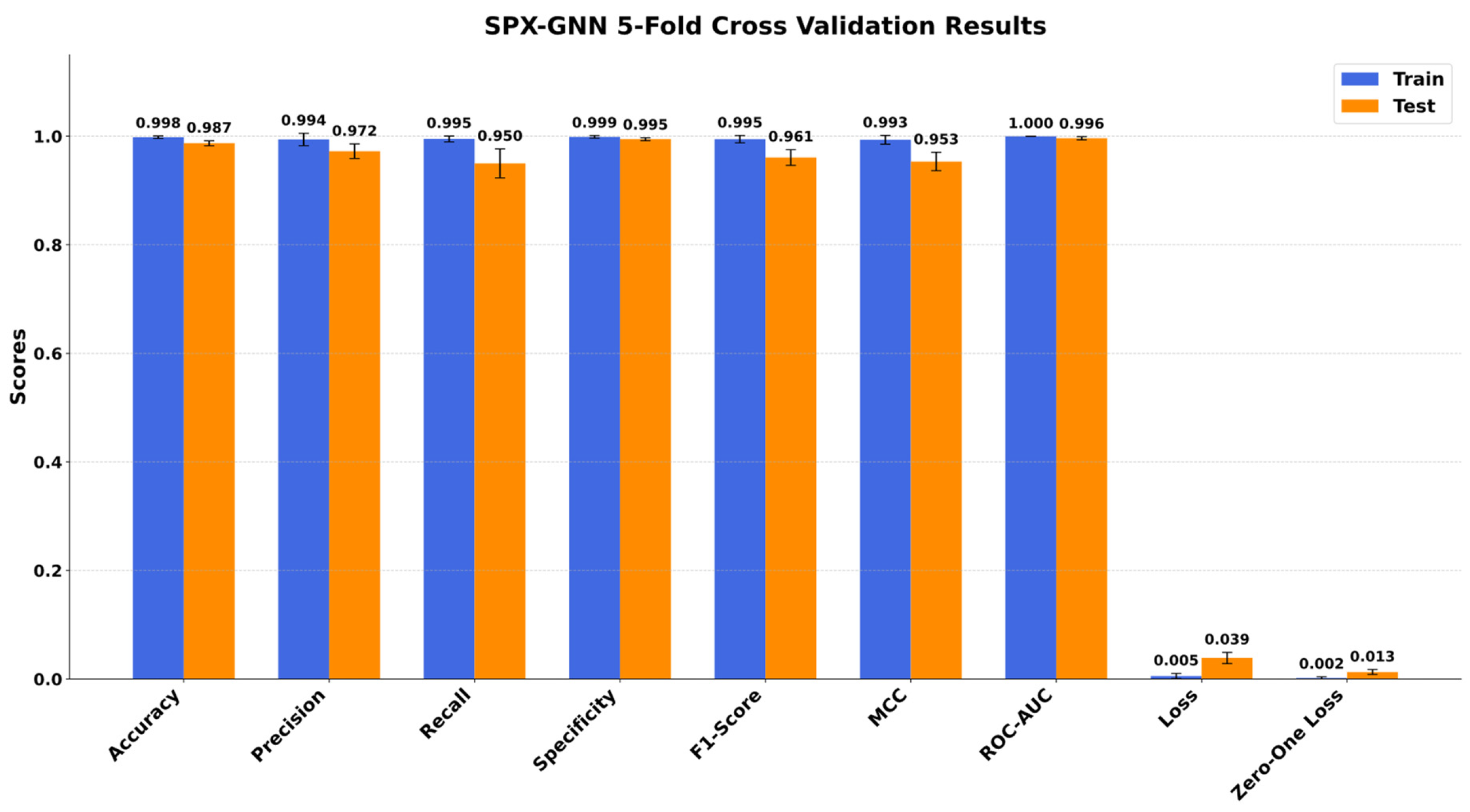

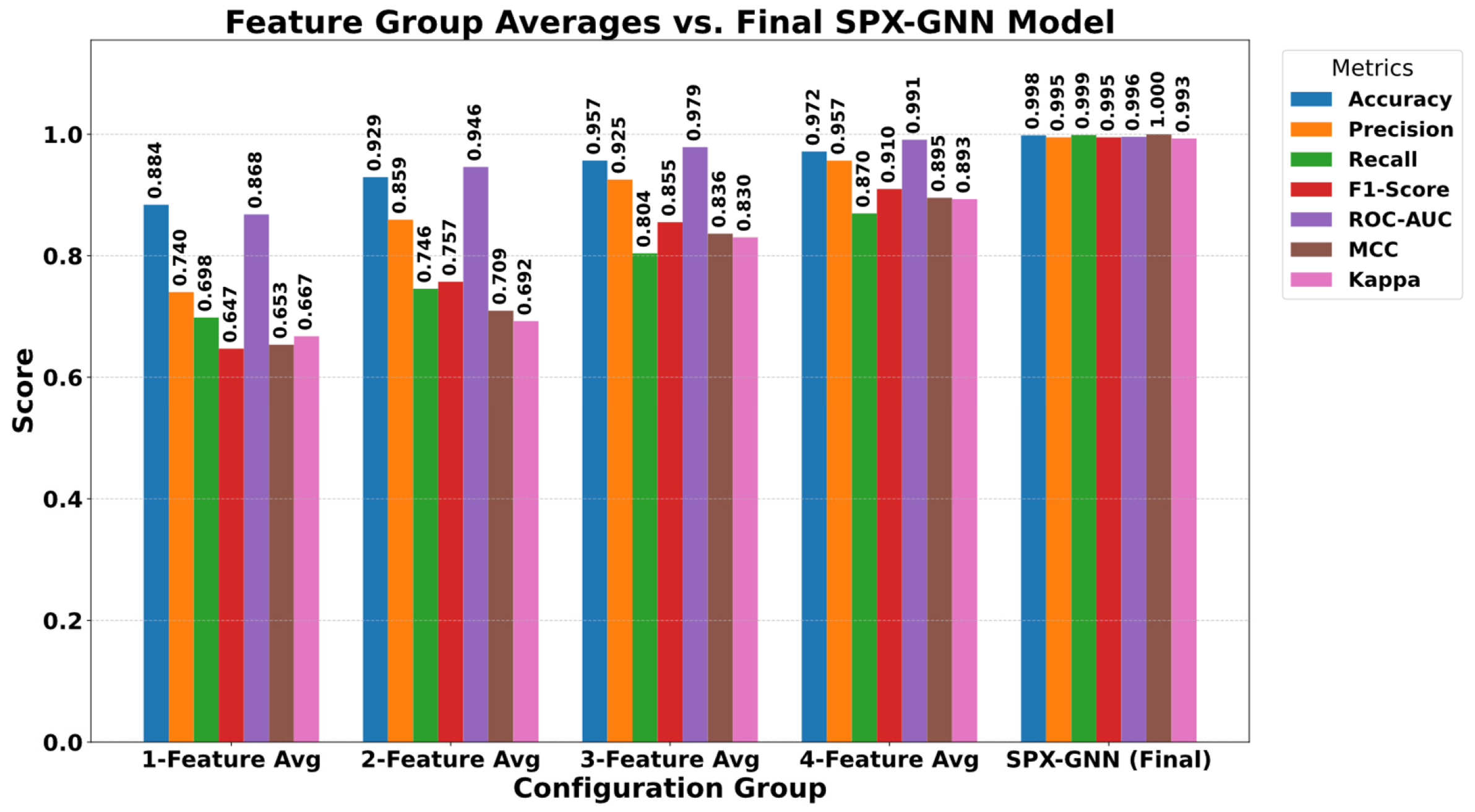

- Demonstrated Practical Impact: The proposed method exhibits superior diagnostic performance with 98.7% accuracy, 96.1% F1-score, and a perfect 100.00% ROC-AUC, validating its effectiveness and reliability for real-world medical imaging tasks.

2. Related Works

3. Proposed Method

4. Materials and Methods

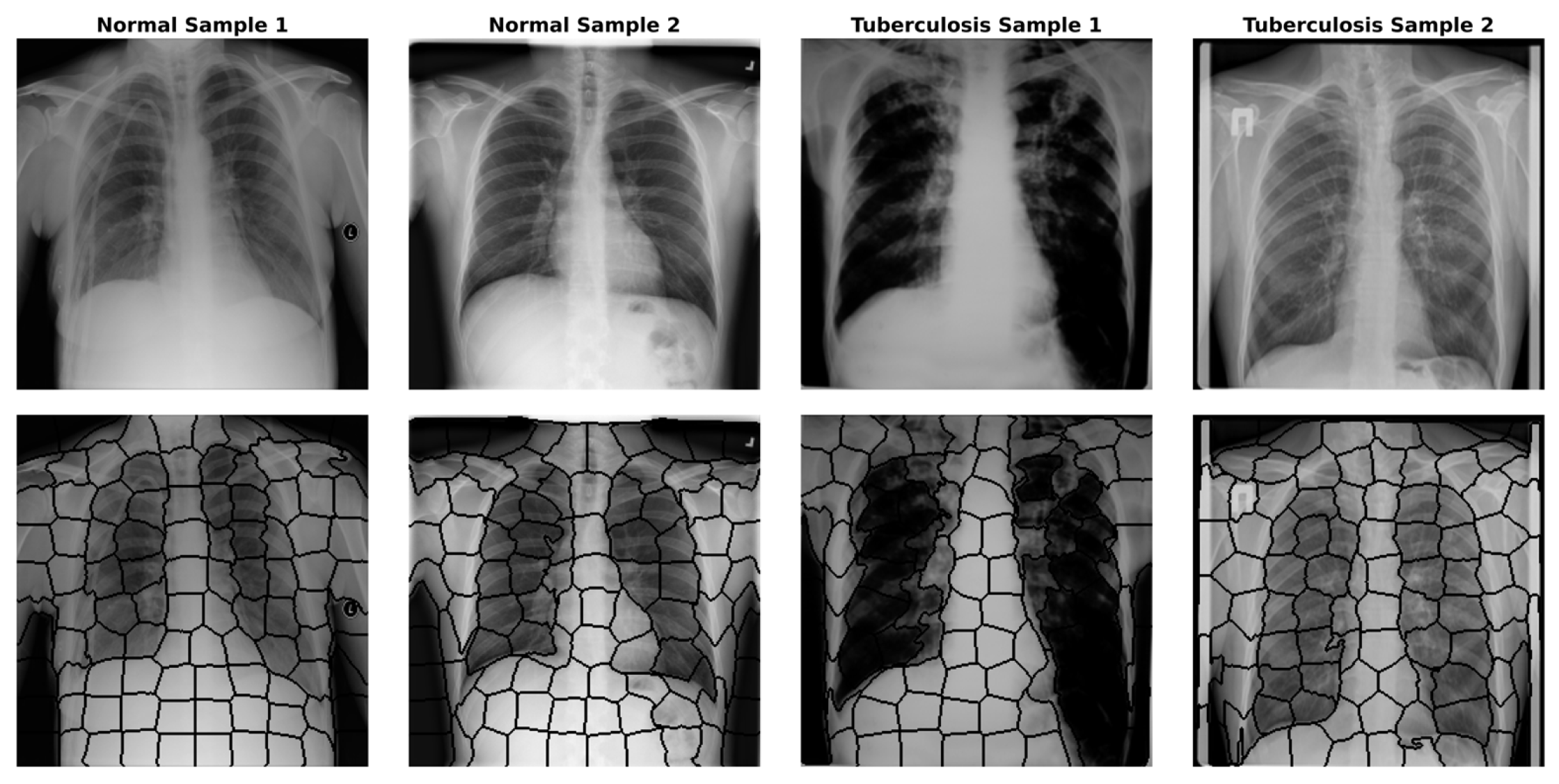

4.1. Dataset

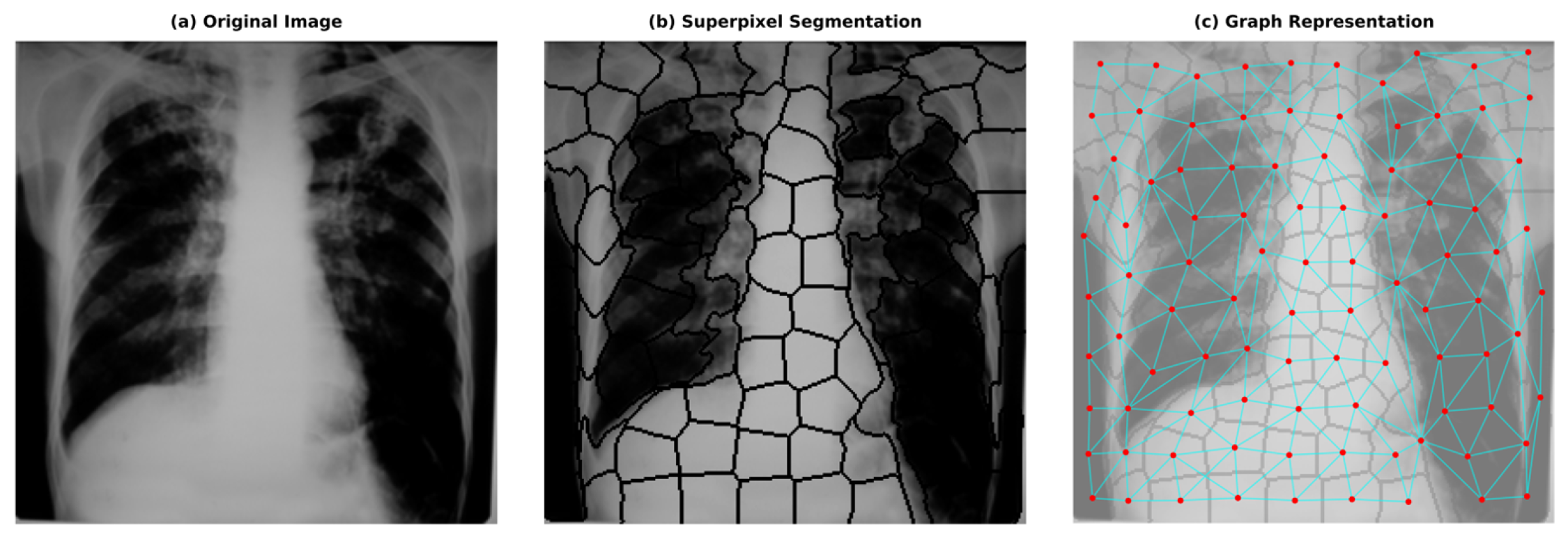

4.2. Image to Graph

- 1-

- Colour and Intensity: Instead of the RGB space, we utilised the CIELAB colour space, which is perceptually uniform. We calculated the mean values of the L, A, and B channels for pixels within to represent average intensity and colour variations, which are crucial for identifying lesions under varying illumination conditions.

- 2-

- Texture Descriptors: Since tuberculosis significantly alters lung tissue texture (e.g., infiltrations or consolidation), we extracted texture features to capture these irregularities. We computed Local Binary Patterns (LBP) histograms (radius = 3, points = 24) to encode micro-texture invariance. Additionally, Haralick features (Contrast, Correlation, Energy, and Homogeneity) were derived from the Grey-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) to quantify structural dependencies at the regional level.

- 3-

- Shape Invariants: To characterise the geometry of segmented regions independent of their orientation or scale, we calculated the seven invariant Hu Moments for each superpixel mask. This helps the model distinguish specific anatomical shapes regardless of patient positioning.

- 4-

- Spatial Location: The normalised centroid coordinates (x,y) were included to allow the GNN to learn position-dependent priors, such as the likelihood of infection in specific lung lobes.

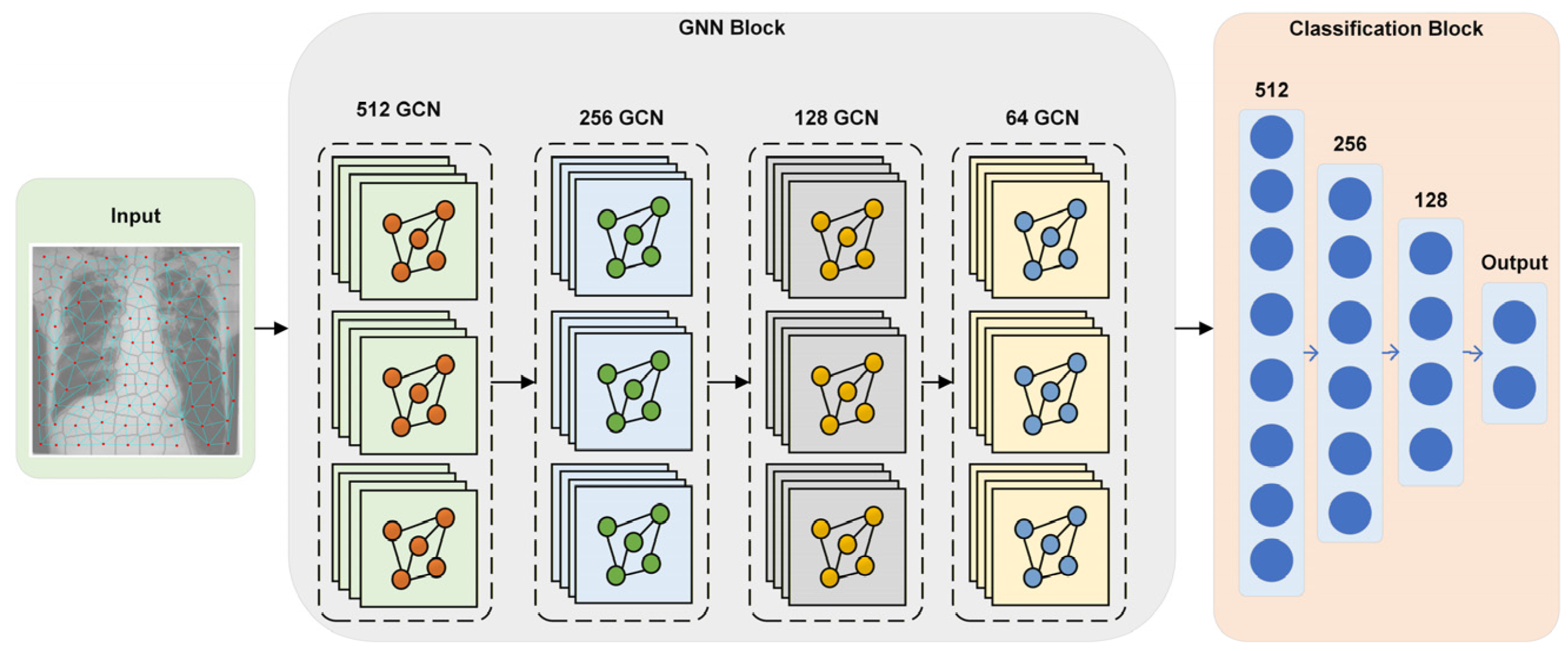

4.3. Graph Neural Network

4.4. Perturbation-Based Explainability

4.5. SPX-GNN Architecture

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

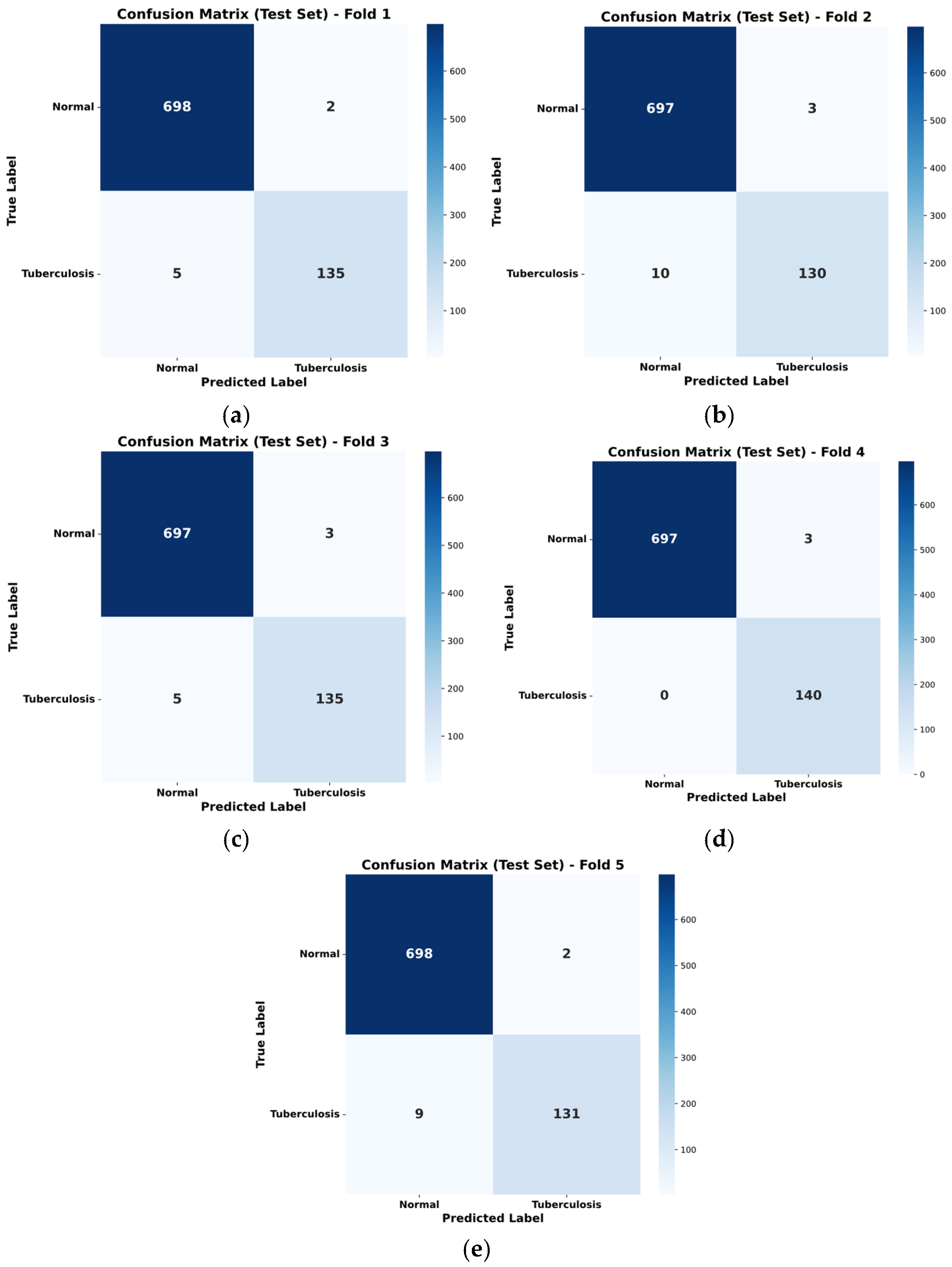

5.2. SPX-GNN Performance

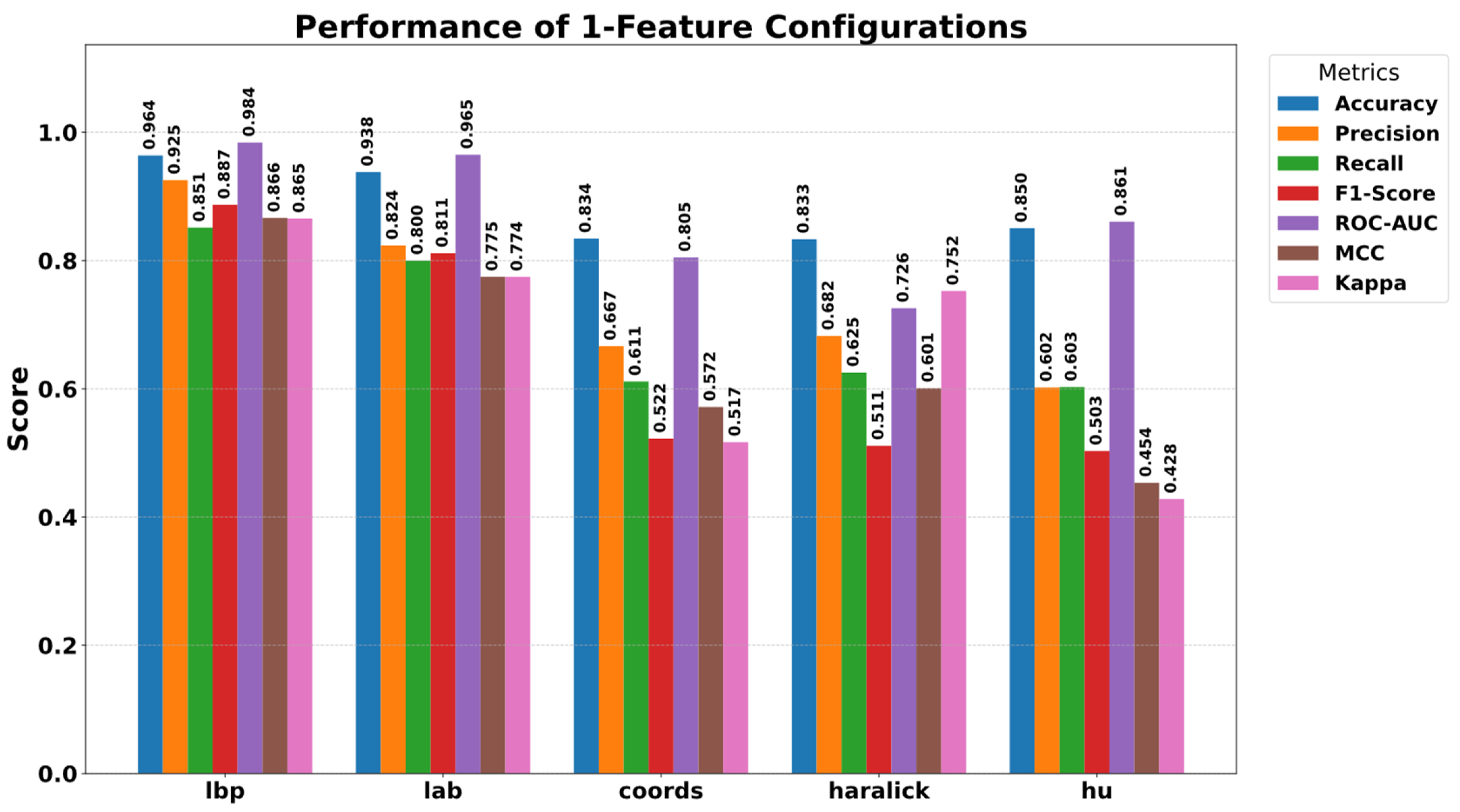

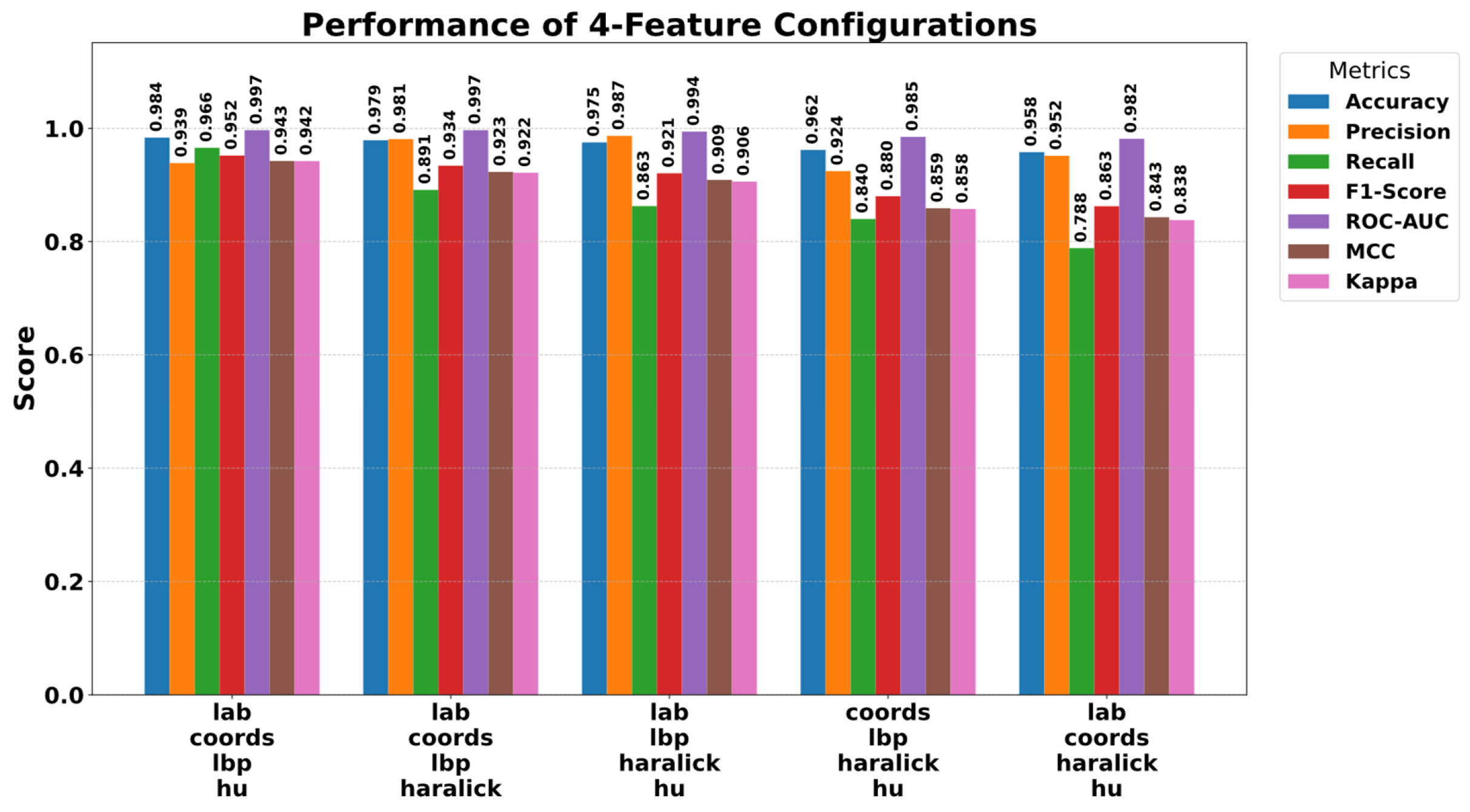

5.3. Ablation Study

5.4. Explainability Results of SPX-GNN

5.5. SOTA Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPX-GNN | Superpixel Explainable Graph Neural Network |

| xAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| LBP | Local Binary Pattern |

| SLIC | Simple Linear Iterative Clustering |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ROC-AUC | Receiver Operating Characteristic–Area Under the Curve |

References

- Silva, M.L.; Cá, B.; Osório, N.S.; Rodrigues, P.N.S.; Maceiras, A.R.; Saraiva, M. Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum: Knowns and unknowns. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagcchi, S. WHO’s global tuberculosis report 2022. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaya, J.; Petersen, E.; Nantanda, R.; Mungai, B.N.; Migliori, G.B.; Amanullah, F.; Lungu, P.; Ntoumi, F.; Kumarasamy, N.; Maeurer, M. The WHO Global Tuberculosis 2021 Report–not so good news and turning the tide back to End TB. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 124, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.K.; Nath, M.K. Efficient segmentation of vessels and disc simultaneously using multi-channel generative adversarial network. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varoquaux, G.; Cheplygina, V. Machine learning for medical imaging: Methodological failures and recommendations for the future. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elyan, E.; Vuttipittayamongkol, P.; Johnston, P.; Martin, K.; McPherson, K.; Moreno-García, C.F.; Jayne, C.; Sarker, M.M.K. Computer vision and machine learning for medical image analysis: Recent advances, challenges, and way forward. Artif. Intell. Surg. 2022, 2, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.K.; Nath, M.K.; Neog, D.R. Efficient segmentation of exudates in color fundus images using wavelets and generative adversarial network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 40905–40935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgul, A.; Karaca, Y.; Pala, M.A.; Çimen, M.E.; Boz, A.F.; Yildiz, M.Z. Chaos Theory, Advanced Metaheuristic Algorithms And Their Newfangled Deep Learning Architecture Optimization Applications: A Review. Fractals 2024, 32, 2430001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.W.; Khan, S.; Gupta, G.; Alabduallah, B.I.; Almjally, A.; Alsolai, H.; Siddiqui, T.; Mellit, A. A study of CNN and transfer learning in medical imaging: Advantages, challenges, future scope. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, M.A.; Yıldız, M.Z. Improving cellular analysis throughput of lens-free holographic microscopy with circular Hough transform and convolutional neural networks. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 176, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasdi Rere, L.M.; Fanany, M.I.; Arymurthy, A.M. Metaheuristic Algorithms for Convolution Neural Network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2016, 2016, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, M.A. Graph-Aware AURALSTM: An Attentive Unified Representation Architecture with BiLSTM for Enhanced Molecular Property Prediction. Mol. Divers. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cui, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, W. A Network Enhancement Method to Identify Spurious Drug-Drug Interactions. IEEE ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2024, 21, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitha, K.; Mahesh, T.R.; Kumar, V.V.; Guluwadi, S. Enhanced tuberculosis detection using Vision Transformers and explainable AI with a Grad-CAM approach on chest X-rays. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, M.A. XP-GCN: Extreme Learning Machines and Parallel Graph Convolutional Networks for High-Throughput Prediction of Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration based on Feature Fusion. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2025, 120, 108755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyamabo, A.K.; Yu, H.; Liu, Z.; Shi, J.Y. Drug-drug interaction prediction with learnable size-Adaptive molecular substructures. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, M.A. DeepInsulin-Net: A Deep Learning Model for Identifying Drug Interactions Leading to Specific Insulin-Related Adverse Events. Sak. Univ. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 8, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P. Everything is connected: Graph neural networks. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 79, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 2020, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadhoud, Y.; Mekhaznia, T.; Bennour, A.; Amroune, M.; Kurdi, N.A.; Aborujilah, A.H.; Al-Sarem, M. From binary to multi-class classification: A two-step hybrid cnn-vit model for chest disease classification based on x-ray images. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirugwe, A.; Tamale, L.; Nyirenda, J. Improving Tuberculosis Detection in Chest X-Ray Images Through Transfer Learning and Deep Learning: Comparative Study of Convolutional Neural Network Architectures. JMIRx Med 2025, 6, e66029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, O.H.; Shuaibu, A.S.; Haq, S.U.; Siddiqui, A.J. AttCDCNet: Attention-enhanced Chest Disease Classification using X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 22nd International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Monastir, Tunisia, 17–20 February 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 891–896. [Google Scholar]

- Yulvina, R.; Putra, S.A.; Rizkinia, M.; Pujitresnani, A.; Tenda, E.D.; Yunus, R.E.; Djumaryo, D.H.; Yusuf, P.A.; Valindria, V. Hybrid Vision Transformer and Convolutional Neural Network for Multi-Class and Multi-Label Classification of Tuberculosis Anomalies on Chest X-Ray. Computers 2024, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.D.; Patil, A. CXR-MultiTaskNet a unified deep learning framework for joint disease localization and classification in chest radiographs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghany, S.A.; Elmogy, M.; Mahmood, M.A.; Abd El-Aziz, A.A. A Robust Tuberculosis Diagnosis Using Chest X-Rays Based on a Hybrid Vision Transformer and Principal Component Analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddharth, G.; Ambekar, A.; Jayakumar, N. Enhanced CoAtNet based hybrid deep learning architecture for automated tuberculosis detection in human chest X-rays. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, S.M.N.; Mamun, M.A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Alam, M.G.R. SynthEnsemble: A fusion of CNN, vision transformer, and Hybrid models for multi-label chest X-ray classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13–15 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, S.; Sampath, P.; Arunachalam, R.; Shanmuganathan, V.; Dhiman, G.; Chakrabarti, P.; Chakrabarti, T.; Margala, M. Early diagnosis and meta-agnostic model visualization of tuberculosis based on radiography images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, M.; Shahi, T.B.; Siku, B.; Neupane, A. Explanatory classification of CXR images into COVID-19, Pneumonia and Tuberculosis using deep learning and XAI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 150, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamud, E.; Fahad, N.; Assaduzzaman, M.; Zain, S.M.; Goh, K.O.M.; Morol, M.K. An explainable artificial intelligence model for multiple lung diseases classification from chest X-ray images using fine-tuned transfer learning. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 12, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisah, S.I.; Muhammad, G. Tuberculosis detection in chest radiograph using convolutional neural network architecture and explainable artificial intelligence. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, B.U.; Sam, D.; Mittal, N.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, S.; Askar, S.S.; Abouhawwash, M. Explainable deep-neural-network supported scheme for tuberculosis detection from chest radiographs. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Khandakar, A.; Kadir, M.A.; Islam, K.R.; Islam, K.F.; Mazhar, R.; Hamid, T.; Islam, M.T.; Kashem, S.; Mahbub, Z. Bin Reliable tuberculosis detection using chest X-ray with deep learning, segmentation and visualization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191586–191601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Shaji, A.; Smith, K.; Lucchi, A.; Fua, P.; Süsstrunk, S. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tan, L.; Zou, Q. DGCL: Dual-graph neural networks contrastive learning for molecular property prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, M.A. CNS-DDI: An Integrated Graph Neural Network Framework for Predicting Central Nervous System Related Drug-Drug Interactions. Bitlis Eren Üniv. Bilim. Derg. 2025, 14, 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Zhao, G.; Xu, Y.; McGuire, T.; Hou, G.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Lopez, O.; Xue, Y.; Xie, X.-Q. GCN-BBB: Deep Learning Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability PharmacoAnalytics with Graph Convolutional Neural (GCN) Network. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipf, T.N. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovs, M.; Kadikis, R.; Ozols, K. Perturbation-based methods for explaining deep neural networks: A survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 150, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Gourisaria, M.K.; Harshvardhan, G.M.; Singh, V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection using CNN ranking approach. In Advanced Computational Paradigms and Hybrid Intelligent Computing, Proceedings of the ICACCP 2021, Sikkim, India, 22–24 March 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 583–596. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, V.; Dhiman, G.; Prakasha, K.; Bahadur, P.; Choraria, A.; M., S.; Prabhu, S.; Chadaga, K.; Viriyasitavat, W.; Kautish, S. AI-assisted tuberculosis detection and classification from chest X-rays using a deep learning normalization-free network model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2399428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasitpuriprecha, C.; Jantama, S.S.; Preeprem, T.; Pitakaso, R.; Srichok, T.; Khonjun, S.; Weerayuth, N.; Gonwirat, S.; Enkvetchakul, P.; Kaewta, C. Drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment recommendation, and multi-class tuberculosis detection and classification using ensemble deep learning-based system. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, R.; Mittal, A.; Sofat, S. Automated TB classification using ensemble of deep architectures. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 31515–31532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, M.H.A.; Hwa, S.K.T.; Bade, A.; Yaakob, R.; Jeffree, M.S. Ensemble deep learning for tuberculosis detection using chest X-ray and canny edge detected images. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-J.; Kim, Y.; Yun, S.; Lim, S.-S.; Kim, J.; Nam, C.-M.; Park, E.-C.; Jung, I.; Yoon, J.-H. Deep learning algorithms with demographic information help to detect tuberculosis in chest radiographs in annual workers’ health examination data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshmrani, G.M.M.; Ni, Q.; Jiang, R.; Pervaiz, H.; Elshennawy, N.M. A deep learning architecture for multi-class lung diseases classification using chest X-ray (CXR) images. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 64, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, S.; Suchitra, S.; Krishnasamy, L.; Sharma, N.; Pathak, N. Stochastic learning-based artificial neural network model for an automatic tuberculosis detection system using chest X-ray images. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 103632–103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, V.T.Q.; Lin, C.-M. An improved densenet deep neural network model for tuberculosis detection using chest x-ray images. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 42839–42849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image to Graph | Super-pixel Number | 100 | The number of superpixels (nodes) targeted by the SLIC algorithm for each image. |

| Super-pixel Compactness | 25 | Adjusts the balance between colour and spatial proximity. Higher values produce more square superpixels. | |

| Gauss Filter Sigma | 0.9 | Standard deviation of the Gaussian smoothing applied to the pre-SLIC image. | |

| GNN Model Architecture | GCN Layer Size | 512, 256, 128, 64 | Kernel size of four GCN layers |

| Dense Layer | 512, 256, 128 | Number of dense layers following the pooling layer | |

| Dropout Rate | 10% | The dropout rate is applied after each GCN and dense layer to prevent overfitting. | |

| Training and Optimisation | Learning Rate | 0.001 | The value that determines the step size of the optimiser. |

| Batch Size | 32 | The number of graphs used in each training iteration. | |

| Maximum Epoch | 100 | The maximum number of iterations the model performs on all training data. | |

| Optimisation Algorithm | Adam | An adaptive momentum-based optimisation algorithm for gradient descent. | |

| Loss Function | Binary Cross-Entropy | Standard loss function for binary classification problems. |

| Reference | Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | F1- Score (%) | ROC-AUC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | ViT-GradCAM | 97.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 98.00 | - |

| [33] | DenseNet | 98.60 | 98.56 | 98.56 | - | - |

| [40] | CNN | 96.71 | - | - | - | - |

| [41] | NFNets | 95.91 | 91.67 | 91.78 | 98.32 | |

| [42] | Transfer Learning | 92.6 | - | - | - | - |

| [41] | NF net model | 96.91 | 91.81 | 98.42 | - | 99.38 |

| [43] | ResNet | 88.24 | 88.42 | 88.00 | - | 93.00 |

| [44] | VGG-16 | 89.77 | 90.91 | - | - | |

| [45] | VGG-19 | 81.50 | 96.20 | - | 92.00 | |

| [46] | VGG19 + CNN | 96.48 | 93.75 | 97.56 | 95.62 | 99.82 |

| [47] | ANN | 98.45 | 98.01 | 96.12 | 95.88 | - |

| [48] | DenseNet | 98.80 | 94.28 | 98.50 | 96.35 | - |

| SPX-GNN (Proposed Method) | GNN | 99.82 ± 0.002 | 99.40 ± 0.011 | 99.50 ± 0.005 | 99.45 ± 0.006 | 100.00 ± 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pala, M.A.; Navdar, M.B. SPX-GNN: An Explainable Graph Neural Network for Harnessing Long-Range Dependencies in Tuberculosis Classifications in Chest X-Ray Images. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243236

Pala MA, Navdar MB. SPX-GNN: An Explainable Graph Neural Network for Harnessing Long-Range Dependencies in Tuberculosis Classifications in Chest X-Ray Images. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243236

Chicago/Turabian StylePala, Muhammed Ali, and Muhammet Burhan Navdar. 2025. "SPX-GNN: An Explainable Graph Neural Network for Harnessing Long-Range Dependencies in Tuberculosis Classifications in Chest X-Ray Images" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243236

APA StylePala, M. A., & Navdar, M. B. (2025). SPX-GNN: An Explainable Graph Neural Network for Harnessing Long-Range Dependencies in Tuberculosis Classifications in Chest X-Ray Images. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243236