DCL-A: An Unsupervised Ultrasound Beamforming Framework with Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss for Single Plane Wave Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

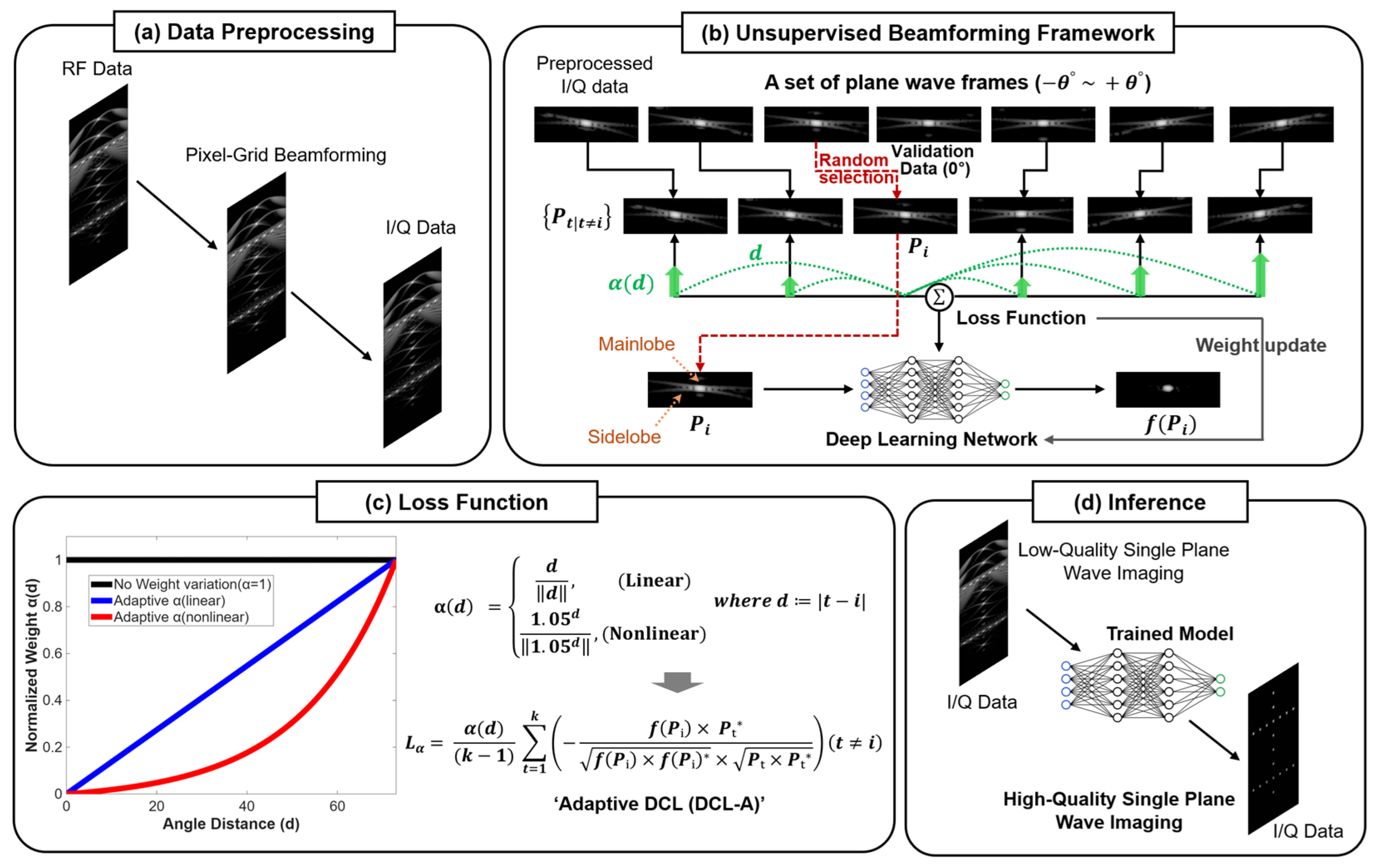

2.1. Unsupervised Beamforming Framework

2.2. Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss

2.3. Network Architecture

2.4. Experimental Setup

2.4.1. Data Preparation

2.4.2. Comparison Methods and Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Training & Validation Curve Analysis

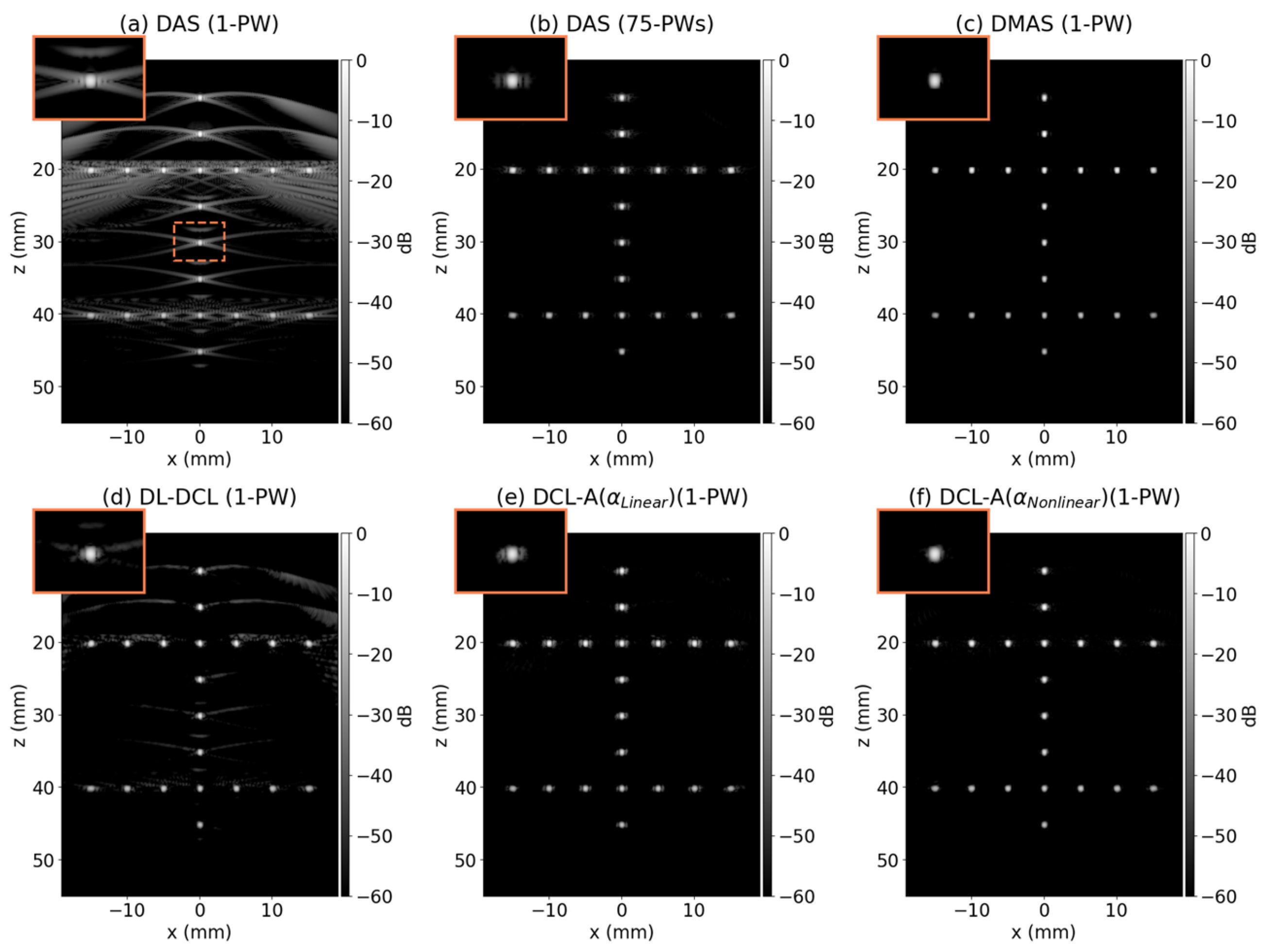

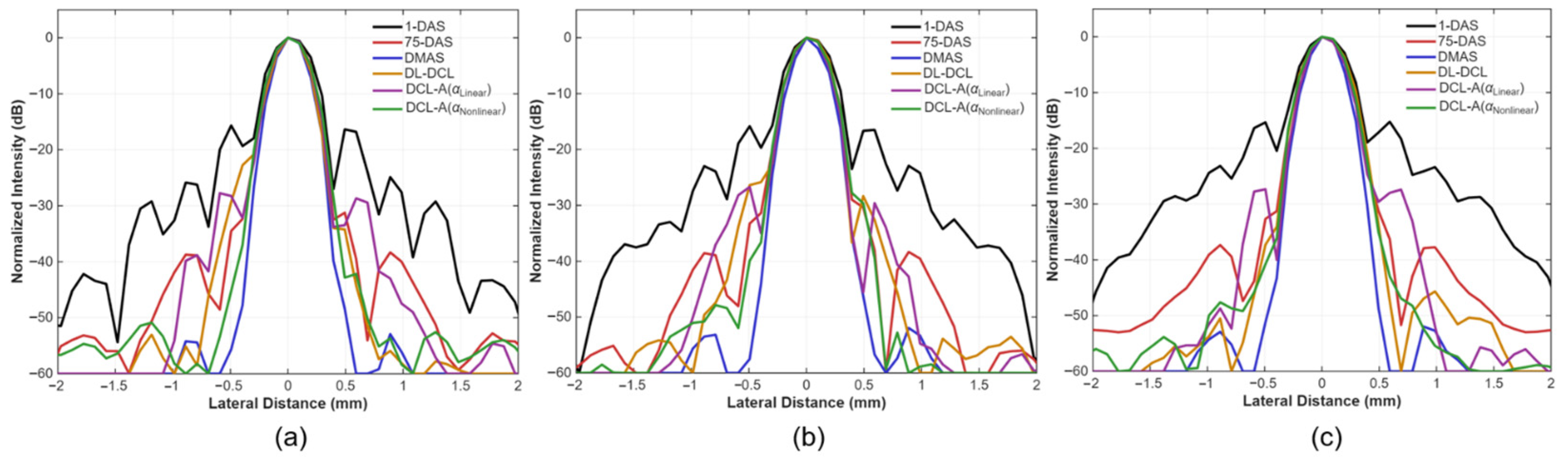

3.2. Simulation Study

3.3. Phantom Study

3.4. In Vivo Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montaldo, G.; Tanter, M.; Bercoff, J.; Benech, N.; Fink, M. Coherent plane-wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography and transient elastography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2009, 56, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanter, M.; Fink, M. Ultrafast imaging in biomedical ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2014, 61, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Go, D.; Song, I.; Yoo, Y. Wide Field-of-View Ultrafast Curved Array Imaging Using Diverging Waves. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiran, E.; Deffieux, T.; Correia, M.; Maresca, D.; Osmanski, B.F.; Sieu, L.A.; Bergel, A.; Cohen, I.; Pernot, M.; Tanter, M. Multiplane wave imaging increases signal-to-noise ratio in ultrafast ultrasound imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2015, 60, 8549–8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Miller, R.J.; Oelze, M.L. Grating lobe reduction in plane-wave imaging with angular compounding using subtraction of coherent signals. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 3308–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-C.; Li, M.-L. Adaptive imaging using the generalized coherence factor. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2003, 50, 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, J.; Parrilla, M.; Fritsch, C. Phase coherence imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2009, 56, 958–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lediju, M.A.; Trahey, G.E.; Byram, B.C.; Dahl, J.J. Short-lag spatial coherence of backscattered echoes: Imaging characteristics. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2011, 58, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Yen, J.T. Improved contrast for high frame rate imaging using coherent compounding combined with spatial matched filtering. Ultrasonics 2017, 78, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrone, G.; Savoia, A.S.; Caliano, G.; Magenes, G. The delay multiply and sum beamforming algorithm in ultrasound B-mode medical imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindal, O.M.H.; Rodriguez-Molares, A.; Austeng, A. The dark region artifact in adaptive ultrasound beamforming. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-C.; Hsieh, P.-Y. Ultrasound baseband delay-multiply-and-sum (BB-DMAS) nonlinear beamforming. Ultrasonics 2019, 96, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Shidara, H.; Ishii, T.; Ito, K.; Aoki, T.; Saijo, Y.; Ohmiya, J. Image quality improvement in single plane-wave imaging using deep learning. Ultrasonics 2025, 145, 107479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Peng, B.; Wei, X.; Luo, J.; Jiang, J. Convolutional Neural Network-Based Speckle Tracking for Ultrasound Strain Elastography: An Unsupervised Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 70, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Pitman, W.M.K.; Yiu, B.Y.S.; Chee, A.J.Y.; Yu, A.C.H. Minimizing Image Quality Loss After Channel Count Reduction for Plane Wave Ultrasound via Deep Learning Inference. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 2849–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-Y.; Lee, P.-Y.; Huang, C.-C. Improving image quality for single-angle plane wave ultrasound imaging with convolutional neural network beamformer. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguon, L.S.; Seo, J.; Seo, K.; Han, Y.; Park, S. Reconstruction for plane-wave ultrasound imaging using modified U-Net-based beamformer. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2022, 98, 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijten, B.; Cohen, R.; de Bruijn, F.J.; Schmeitz, H.A.W.; Mischi, M.; Eldar, Y.C.; van Sloun, R.J.G. Adaptive Ultrasound Beamforming Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 3967–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, C.; Luo, J. Ultrasound image reconstruction from plane wave radio-frequency data by self-supervised deep neural network. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 70, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, X.; Qi, Y. Ultrafast Plane Wave Imaging with Line-Scan-Quality Using an Ultrasound-Transfer Generative Adversarial Network. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasih, M.; Ahmad, S.; Almekkawy, M. A robust cascaded deep neural network for image reconstruction of single plane wave ultrasound RF data. Ultrasonics 2023, 132, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Park, S.; Kang, J.; Yoo, Y. Deep coherence learning: An unsupervised deep beamformer for high quality single plane wave imaging in medical ultrasound. Ultrasonics 2024, 143, 107408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jia, M.; Lin, T.-Y.; Song, Y.; Belongie, S.J. Class-Balanced Loss Based on Effective Number of Samples. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.05555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, M.; Sala, E.; Schönlieb, C.-B.; Rundo, L. Unified Focal loss: Generalising Dice and cross entropy-based losses to handle class imbalanced medical image segmentation. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2022, 95, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C.L.; Moradi, M.; Tang, H.; Syeda-Mahmood, T. 3D Segmentation with Exponential Logarithmic Loss for Highly Unbalanced Object Sizes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Granada, Spain, 16–20 September 2018; pp. 612–619. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9351, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2019), New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liebgott, H.; Rodriguez-Molares, A.; Cervenansky, F.; Jensen, J.A.; Bernard, O. Plane-Wave Imaging Challenge in Medical Ultrasound. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Tours, France, 18–21 September 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, D.; Wiacek, A.; Goudarzi, S.; Rothlübbers, S.; Asif, A.; Eickel, K.; Eldar, Y.C.; Huang, J.; Mischi, M.; Rivaz, H.; et al. Deep Learning for Ultrasound Image Formation: CUBDL Evaluation Framework and Open Datasets. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 3466–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.Q.; Prager, R.W. High-Resolution Ultrasound Imaging with Unified Pixel-Based Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J. ZNorm: Z-Score Gradient Normalization Accelerating Skip-Connected Network Training without Architectural Modification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01215. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, V.; Polichetti, M. So you think you can DAS? A viewpoint on delay-and-sum beamforming. Ultrasonics 2021, 111, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kang, J.; Yoo, Y. Automatic dynamic range adjustment for ultrasound B-mode imaging. Ultrasonics 2015, 56, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassaroli, E.; Crake, C.; Scorza, A.; Kim, D.S.; Park, M.A. Image quality evaluation of ultrasound imaging systems: Advanced B-modes. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2019, 20, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rodriguez-Molares, A.; Rindal, O.M.H.; D’hooge, J.; Måsøy, S.E.; Austeng, A.; Bell, M.A.L.; Torp, H. The generalized contrast-to-noise ratio: A formal definition for lesion detectability. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2020, 67, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, S.; Sohn, H.-Y.; Song, T.-K.; Yoo, Y.M. Coded excitation for ultrasound tissue harmonic imaging. Ultrasonics 2010, 50, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Go, D.; Song, I.; Yoo, Y. Ultrafast Power Doppler Imaging Using Frame-Multiply-and-Sum-Based Nonlinear Compounding. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Kim, D.; Chang, S.; Kang, J.; Yoo, Y. A system-on-chip solution for deep learning-based automatic fetal biometric measurement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Source | Simulation | Phantom | In Vivo | PW Span Angle (°) | Number of PW Angles | Number of Sequences | Number of Frames | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Validation/Test | ||||||||

| PICMUS [29] | 2 | 2 | 2 | [−16, 16] | 75 | 6 | 438 | 6 | |

| CUBDL [30] | INS | - | 5 | - | [−16, 16] | 75 | 5 | 365 | 5 |

| MYO | - | 5 | - | [−15, 15] | 75 | 5 | 365 | 5 | |

| UFL | - | 2 | - | [−15, 15] | 75 | 2 | 146 | 2 | |

| JHU | - | - | 11 | [−8, 8] | 75 (73) | 11 | 803 | 11 | |

| TSH | - | 50 | - | [−15, 15] | 31 | 50 | 1450 | 50 | |

| Total | 2 | 64 | 13 | - | - | 79 | 3567 | 79 | |

| Metrics | Depth | DAS (1-PW) | DAS (75-PWs) | DMAS | DL-DCL | DCL-A ) | DCL-A ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWHM [mm] | 20 mm | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.37 |

| 30 mm | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.37 | |

| 40 mm | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.40 | |

| STD | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| PRSLL [dB] | 20 mm | −16.36 | −31.25 | −39.81 | −34.23 | −28.67 | −42.18 |

| 30 mm | −16.67 | −30.38 | −46.25 | −28.37 | −29.59 | −39.47 | |

| 40 mm | −15.24 | −36.30 | −48.65 | −45.66 | −27.41 | −46.94 | |

| STD | 0.75 | 3.20 | 4.57 | 8.79 | 1.09 | 3.78 |

| DAS (1-PW) | DAS (75-PWs) | DMAS | DL-DCL | DCL-A ) | DCL-A ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWHM [mm] | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| PRSLL [dB] | 3.00 | 5.78 | 12.82 | 4.26 | 3.03 | 4.59 |

| DAS (1-PW) | DAS (75-PWs) | DMAS | DCL | DCL-A ) | DCL-A ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNR [dB] | 1.61 | 4.43 | 3.15 | 5.68 | 5.65 | 5.70 |

| gCNR | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, T.; Hwang, S.; Song, M.; Kang, J. DCL-A: An Unsupervised Ultrasound Beamforming Framework with Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss for Single Plane Wave Imaging. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3193. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243193

Kim T, Hwang S, Song M, Kang J. DCL-A: An Unsupervised Ultrasound Beamforming Framework with Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss for Single Plane Wave Imaging. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3193. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243193

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Taejin, Seongbin Hwang, Minho Song, and Jinbum Kang. 2025. "DCL-A: An Unsupervised Ultrasound Beamforming Framework with Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss for Single Plane Wave Imaging" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3193. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243193

APA StyleKim, T., Hwang, S., Song, M., & Kang, J. (2025). DCL-A: An Unsupervised Ultrasound Beamforming Framework with Adaptive Deep Coherence Loss for Single Plane Wave Imaging. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3193. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243193