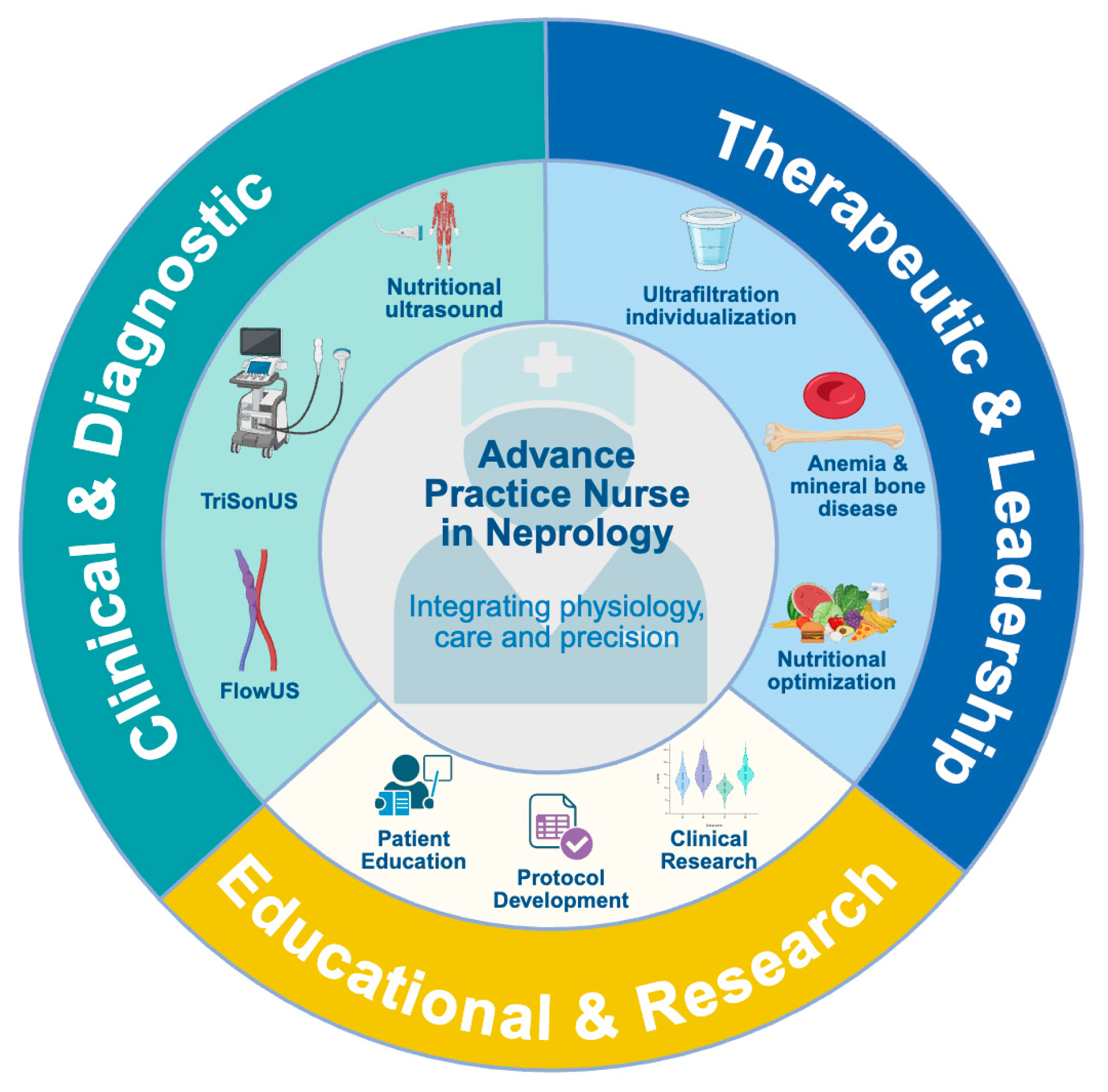

Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice: Seeing Beyond the Numbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

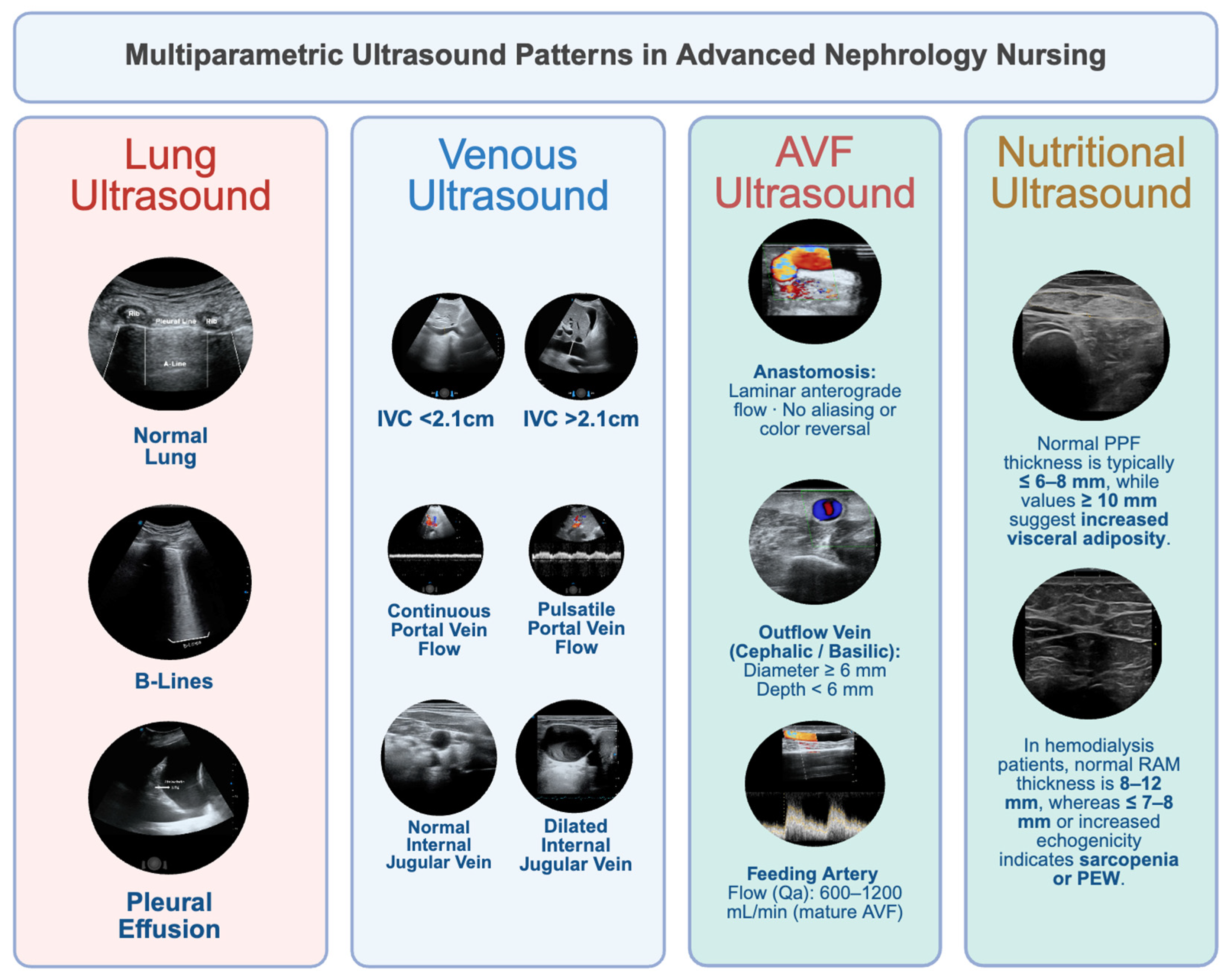

2. Clinical and Diagnostic Challenges in Volume Assessment

3. A Multiparametric Ultrasound Approach to Assessing Congestion

3.1. Lung Ultrasound

3.2. Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Ultrasound

3.3. Portal Vein Doppler

3.4. Hepatic and Intrarenal Vein Doppler

3.5. The Extended VExUS Concept

3.6. Nutritional Ultrasound: Linking Muscle Health and Congestion

4. Defining the Role of Advanced Practice Nurses in PoCUS-Enhanced Nephrology Care

5. Integration of PoCUS into Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice

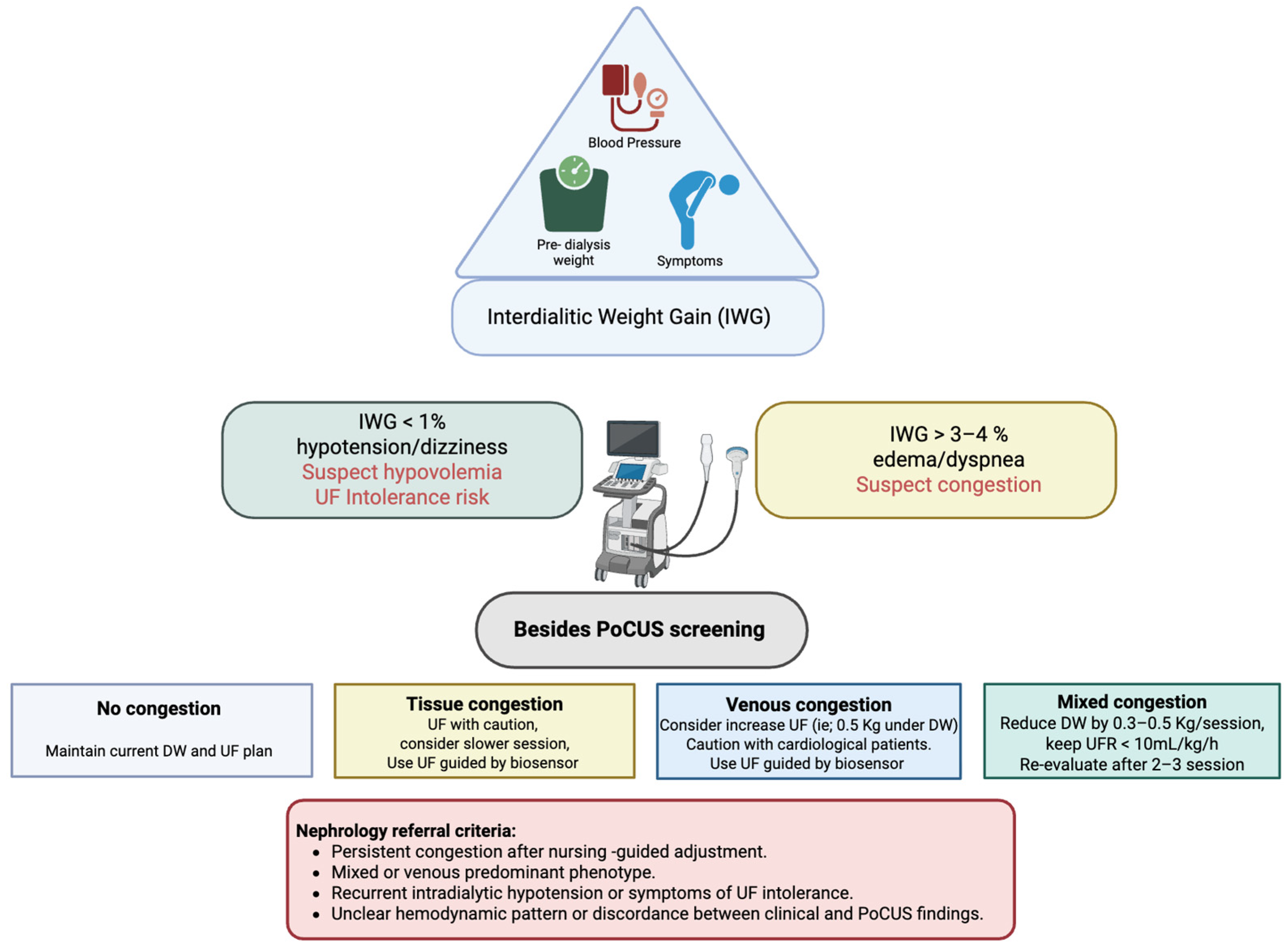

6. Clinical Protocol: Nursing-Led PoCUS Workflow

- Step 1—Initial Assessment

- IWG < 1% or presence of hypotension/dizziness suggests hypovolemia and a high risk of UF intolerance.

- IWG > 3–4% or presence of dyspnea or edema indicates suspected congestion.

- Step 2—First Decision

- Non-congestive phenotype: When no B-lines are detected on LUS and the IVC shows normal diameter and collapsibility, a conservative UF strategy or temporary UF pause is advised. The nurse continues close clinical and hemodynamic monitoring.

- Suspected congestion: If clinical findings suggest fluid overload, the nurse proceeds to focused PoCUS evaluation before initiating dialysis, as recommended in studies validating LUS and IVC assessment in hemodialysis care

- Step 3—Bedside PoCUS Screening

- No congestion: Maintain UF target and schedule next evaluation; consider cardiac PoCUS if diagnostic uncertainty persists.

- Predominant tissue congestion: Initiate a controlled decongestive strategy with gradual dry-weight reduction and biosensor-guided UF. If dyspnea persists, consider extended UF guided by biosensor feedback and refer for cardiac PoCUS to assess left-sided pressures.

- Predominant venous congestion: Use progressive decompression rather than aggressive UF; refer for cardiac PoCUS to evaluate right ventricular function.

- Mixed congestion: Implement a stepwise UF approach, targeting UF < 10 mL/kg/h, reducing dry weight by 0.3–0.5 kg per session, and re-evaluating after 2–3 sessions. Refer for Cardiac PoCUS may help determine the dominant mechanism of congestion.

7. Implementation of the Nursing-Led PoCUS Program: Our Experience

8. Operational and Clinical Integration

- Baseline assessment: at program initiation to establish individual hemodynamic and nutritional profiles.

- Monthly reassessment: coinciding with laboratory and clinical reviews.

- Event-triggered evaluation: during episodes of clinical congestion, hospitalization, or UF intolerance.

9. Toward Precision Nursing

10. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Kramer, A.; Rychlík, I.; Nangaku, M.; Yanagita, M.; Jager, K.J.; Caskey, F.J.; Stel, V.S.; Kashihara, N.; Kuragano, T.; et al. Maintaining kidney health in aging societies: A JSN and ERA call to action. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Society of Nephrology (ISN). Global Kidney Health Atlas. In Improving Kidney Care Worldwide, 3rd ed.; International Society of Nephrology: Cranford, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.; Weir, M.R. Dry-Weight: A Concept Revisited in an Effort to Avoid Medication-Directed Approaches for Blood Pressure Control in Hemodialysis Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flythe, J.E.; Chang, T.I.; Gallagher, M.P.; Lindley, E.; Madero, M.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Unruh, M.L.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Weiner, D.E.; Cheung, M.; et al. Blood pressure and volume management in dialysis: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, I.; Romero-González, G.; Arias, M.; Vegad, A.; Deirae, J.; Molinaf, P.; Ojedag, R.; Maduellc, F. En nombre del grupo de trabajo de Hemodiálisis en centro. Individualización y desafíos para la hemodiálisis de la próxima década. Nefrología 2023, 44, 459–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriopol, D.; Hogas, S.; Voroneanu, L.; Onofriescu, M.; Apetrii, M.; Oleniuc, M.; Moscalu, M.; Sascau, R.; Covic, A. Predicting mortality in haemodialysis patients: A comparison between lung ultrasonography, bioimpedance data and echocardiography parameters. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2851–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, E.; Faragli, A.; Herrmann, A.; Lo Muzio, F.P.; Estienne, L.; Nigra, S.G.; Bellasi, A.; Deferrari, G.; Ricevuti, G.; Di Somma, S.; et al. Bioimpedance Analysis in CKD and HF Patients: A Critical Review of Benefits, Limitations, and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-González, G.; Manrique, J.; Slon-Roblero, M.F.; Husain-Syed, F.; De la Espriella, R.; Ferrari, F.; Bover, J.; Ortiz, A.; Ronco, C. PoCUS in nephrology: A new tool to improve our diagnostic skills. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 16, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Espriella, R.; Cobo, M.; Santas, E.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Fudim, M.; Girerd, N.; Miñana, G.; Górriz, J.L.; Bayés-Genís, A.; Núñez, J. Assessment of filling pressures and fluid overload in heart failure: An updated perspective. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2023, 76, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, A.; Girerd, N.; Le Breton, H.; Galli, E.; Latar, I.; Fournet, M.; Mabo, P.; Schnell, F.; Leclercq, C.; Donal, E. Diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound for identification of elevated left ventricular filling pressure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 281, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longino, A.; Martin, K.; Leyba, K.; Siegel, G.; Gill, E.; Douglas, I.S.; Burke, J. Correlation between the VExUS score and right atrial pressure: A pilot prospective observational study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Romero-González, G.; Soliman-Aboumarie, H.; Kazory, A. Unlocking the Potential of VExUS in Assessing Venous Congestion. In The Art of Doing It Right; Cardiorenal Medicine: Basel, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Argaiz, E.R. VExUS Nexus: Bedside Assessment of Venous Congestion. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2021, 28, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Olusanya, O.; Watchorn, J.; Bramham, K.; Hutchings, S. Utility of the Venous Excess Ultrasound (VEXUS) score to track dynamic change in volume status in patients undergoing fluid removal during haemodialysis—The ACUVEX study. Ultrasound J. 2024, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaiz, E.R.; Cruz, N.; Gamba, G. Evaluation of rapid changes in haemodynamic status by Point-of-Care Ultrasound: A useful tool in cardionephrology. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Torino, C.; Tripepi, R.; Tripepi, G.; D’arrigo, G.; Postorino, M.; Gargani, L.; Sicari, R.; Picano, E.; Mallamaci, F. Pulmonary congestion predicts cardiac events and mortality in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, C.; Torino, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Sarafidis, P.; Papagianni, A.; Ekart, R.; Hojs, R.; Klinger, M.; Letachowicz, K.; Fliser, D.; et al. A randomized multicenter trial on a lung ultrasound–guided treatment strategy in patients on chronic hemodialysis with high cardiovascular risk. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, K.A.; Bonomo, J.B.; Ballman, K. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography for Advanced Practice Providers: A Training Initiative. J. Nurse Pract. 2023, 19, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, M.; Bennett, P.N.; Currey, J.; Hutchinson, A.M. Nurses’ perceptions of point-of-care ultrasound for haemodialysis access assessment and guided cannulation: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 8116–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, E.J. Ultrasonography for Advanced Practice Providers and Nursing Programs. In Ultrasound Program Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 153–162. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-86341-7_12 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Zhang, Y. What is nursing in advanced nursing practice? Applying theories and models to advanced nursing practice—A discursive review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 4842–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Almeida, J.M.; García-García, C.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Pomard, M.D.B.; Cornejo-Parejae, I.M.; Medinaf, B.F.; de Luis Románg, D.A.; Guerreroh, D.B.; Lesmesi, I.B.; Madueño, F.J.T. Nutritional ultrasound®: Conceptualisation, technical considerations and standardisation. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 70, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- De La Flor, J.C.; García-Menéndez, E.; Romero-González, G.; Rodríguez Tudero, C.; Jiménez Mayor, E.; Florit Mengual, E.; Moral Berrio, E.; Soria Morales, B.; Cieza Terrones, M.; Cigarrán Guldris, S. Morphofunctional Assessment of Malnutrition and Sarcopenia Using Nutritional Ultrasonography in Patients Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Ronco, C.; Kazory, A. Diagnosis of Fluid Overload: From Conventional to Contemporary Concepts. Cardiorenal Med. 2022, 12, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, Q.; Krishnaswamy, P.; Kazanegra, R.; Harrison, A.; Amirnovin, R.; Lenert, L.; Clopton, P.; Alberto, J.; Hlavin, P.; Maisel, A.S. Utility of B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in an urgent-care setting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.; Mebazaa, A.; Rocca, H.B.; Martens, P.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.W.; Orso, F.; Rossignol, P.; et al. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion—A position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabinor, M.; Davies, S.J. The use of bioimpedance spectroscopy to guide fluid management in patients receiving dialysis. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2018, 27, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Maestro, A.; Fernández-Martínez, J.; López-López, L.; Solé-González, E.; Vives-Borrás, M.; Montero, S.; Mesado, N.; Pirla, M.J.; Mirabet, S.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of subclinical pulmonary congestion at discharge in patients with acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 2621–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, S.; Friedrich, B.; Peter, A.; Häring, H.U.; Heyne, N.; Artunc, F. Systemic haemodynamics in haemodialysis: Intradialytic changes and prognostic significance. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaud, B.; Chazot, C.; Koomans, J.; Collins, A. Fluid and hemodynamic management in hemodialysis patients: Challenges and opportunities. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2019, 41, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, E.M.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Damman, K.; Dinh, W.; Gustafsson, F.; Goldsmith, S.; Burkhoff, D.; Zannad, F.; Udelson, J.E.; Voors, A.A. Congestion in heart failure: A contemporary look at physiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picano, E.; Scali, M.C.; Ciampi, Q.; Lichtenstein, D. Lung Ultrasound for the Cardiologist. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, N.; Mendrala, K.; Skoczyński, S.; Pasquier, M.; Mazur, P.; Garcia, E.; Darocha, T. Basics of Point-of-Care Lung Ultrasonography. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, N.; Koratala, A. Quantitative Lung Ultrasonography for the Nephrologist: Applications in Dialysis and Heart Failure. Kidney360 2021, 10.34067/KID.0003972021. Available online: https://kidney360.asnjournals.org/content/early/2021/11/11/KID.0003972021 (accessed on 21 November 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koratala, A.; Kazory, A. An Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound: Laennec to Lichtenstein. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2021, 28, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torino, C.; Gargani, L.; Sicari, R.; Letachowicz, K.; Ekart, R.; Fliser, D.; Covic, A.; Siamopoulos, K.; Stavroulopoulos, A.; Massy, Z.A.; et al. The agreement between auscultation and lung ultrasound in hemodialysis patients: The LUST study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, J.; Chandrashekhar, Y.; Braunwald, E. Time to Add a Fifth Pillar to Bedside Physical Examination: Inspection, Palpation, Percussion, Auscultation, and Insonation. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Reisinger, N. Venous Excess Doppler Ultrasound for the Nephrologist: Pearls and Pitfalls. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Villarreal, M.A.J.; Aguirre-Villarreal, D.; Vidal-Mayo, J.J.; Argaiz, E.R.; García-Juárez, I. Correlation of Internal Jugular Vein Collapsibility With Central Venous Pressure in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 1684–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klangthamneam, S.; Meemook, K.; Petnak, T.; Sonkaew, A.; Assavapokee, T. Correlation between right atrial pressure measured via right heart catheterization and venous excess ultrasound, inferior vena cava diameter, and ultrasound-measured jugular venous pressure: A prospective observational study. Ultrasound J. 2024, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koratala, A.; Argaiz, E.R.; City, M. Femoral Vein Doppler for Guiding Ultrafiltration in End-Stage Renal Disease: A Novel Addition to Bedside Ultrasound. Cardiovasc. Imaging Case Rep. 2024, 8, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, M.; Girgin, S.; Ceylan, S.; Özcan, B.; Öztürk, Y.; Okyar Baş, A.; Koca, M.; Balcı, C.; Doğu, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; et al. The Role of Muscle Ultrasonography to Diagnose Malnutrition and Sarcopenia in Maintenance Hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2024, 34, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Morone, C.; Parente, J.; Taylor, S.; Springer, C.; Doyle, P.; Temin, E.; Shokoohi, H.; Liteplo, A. Advanced practice providers proficiency-based model of ultrasound training and practice in the ED. JACEP Open 2022, 3, e12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, N.; Li, Z.; Dong, X.; Chen, G.; Cao, L. The Experiences of Critical Care Nurses Implementing Point-Of-Care Ultrasound: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2025, 30, e70104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totenhofer, R.; Luck, L.; Wilkes, L. Point of care ultrasound use by Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners in clinical practice: An integrative review. Collegian 2021, 28, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.S.N.; Brown, E.A.; Cheung, M.; Figueiredo, A.E.; Hurst, H.; King, J.M.; Mehrotra, R.; Pryor, L.; Walker, R.C.; Wasylynuk, B.A.; et al. The Role of Nephrology Nurses in Symptom Management—Reflections on the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Controversies Conference on Symptom-Based Complications in Dialysis Care. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Chiu, J.; Kha, U.; Khan, B.A.; Ying, L.; Ngoh, C. #4877 The Effect of Nurse-Led 8-Zone Lung Ultrasound Guided Titration of Dry Weight on Hypertension in Apparently Euvolaemic Haemodialysis Patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, gfad063c_4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, T.; Heldeweg, M.; Tulleken, A.M.; Verlaan, B.; Floor, L.; Eijsenga, A.; Lust, E.; Gelissen, H.; Girbes, A.; Elbers, P.; et al. Effects of nurse delivered thoracic ultrasound on management of adult intensive care unit patients: A prospective observational study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, G.H.; Norekval, T.M.; Haug, H.H.; Skjetne, K.; Kleinau, J.O.; Graven, T.; Dalen, H. Adding point of care ultrasound to assess volume status in heart failure patients in a nurse-led outpatient clinic. A Randomised Study. Heart 2015, 102, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalen, H.; Gundersen, G.H.; Skjetne, K.; Haug, H.H.; O Kleinau, J.; Norekval, T.M.; Graven, T. Feasibility and reliability of pocket-size ultrasound examinations of the pleural cavities and vena cava inferior performed by nurses in an outpatient heart failure clinic. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 14, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Jaensch, A.; Childs, J.; McDonald, S. Evaluation of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) training on arteriovenous access assessment and cannula placement for haemodialysis. J. Vasc. Access 2024, 25, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, I.; Stirbu, O.; Schiller, A.; Gadalean, F.; Bob, F. Point-of-Care Arterio-Venous Fistula Ultrasound in the Outpatient Hemodialysis Unit—A Survey on the Nurses’ Perspective. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-González, G.; Argaiz, E.R.; Koratala, A.; González, D.A.; Vives, M.; Juega, J.; Soler-Majoral, J.; Graterol, F.; Perezpayá, I.; Rodriguez-Chitiva, N.; et al. Towards standardization of POCUS training in Nephrology: The time is NOW. Nefrologia 2024, 44, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Argaiz, E.R.; Romero-González, G.; Reisinger, N.; Anwar, S.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Bhasin-Chhabra, B.; Diniz, H.; Gallardo, M.A.V.; Torres, F.G.; et al. Point-of-care ultrasound training in nephrology: A position statement by the International Alliance for POCUS in Nephrology. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Clinical Area | Authors (Year); Journal | Design/N | Technique | Operator | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hemodialysis | Lee et al. [49] | Pragmatic intervention, n = 13 HD patients | 8-zone LUS | Nurses | Nurse-led LUS-guided dry-weight titration was feasible and safe, showing a trend toward lower ambulatory blood pressure. | Small sample size (n = 13) and single-center design; short follow-up; surrogate outcomes only; limited generalizability. |

| 2 | Critical care (mixed ICU) | Smits et al. [50] | Prospective observational | Thoracic PoCUS (LUS + pleura) | ICU nurses (“UltraNurses”) | Nurse-performed PoCUS led to changes in clinical management in >25% of cases, mainly affecting fluid decisions within 8 h. | Observational study without control group; heterogeneous ICU population; findings may not extrapolate to chronic dialysis settings. |

| 3 | Heart failure (outpatient) | Gundersen et al. [51] | Randomised controlled trial, HF clinic | LUS + IVC | Heart-failure nurses | Nurse-performed ultrasound improved volume assessment accuracy and altered management compared with standard evaluation. | Single-clinic setting; specialized HF nurses may not reflect training profiles of dialysis staff; potential learning-curve effects. |

| 4 | Heart failure (outpatient) | Dalen et al. [52] | Observational, HF clinic | LUS + IVC | Nurses | High feasibility and good agreement with reference sonographers for pleural effusion and IVC evaluation after short training. | Small sample and observational design; moderate inter-operator variability; no long-term clinical outcomes measured. |

| 5 | Hemodialysis vascular access | Hill K et al. [53] | Pre-test/post-test training study, n = 15 nurses + 17 patients | AVF assessment + cannula placement | HD nurses | After PoCUS education, nurses reported increased confidence in cannulation; patients supported PoCUS use and it potentially avoided transfers due to cannulation difficulties. | Pre/post design without randomization; small cohort; subjective nurse-reported outcomes; lacks procedural performance metrics. |

| 6 | Hemodialysis vascular access | Grosu I et al. [54] | Survey, outpatient HD unit | AVF PoCUS assessment | HD nursing staff | Nurses viewed AVF-PoCUS as a useful tool; positive attitude toward implementation, though confidence in cannulation decreased slightly over 5 years. | Survey-based methodology; self-reported confidence prone to bias; absence of objective ultrasound performance data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Lahosa, A.; Moreno-Millán, S.; Sanchez-García, M.C.; Sanchez-Cardenas, M.; Steiss, C.; Escobar, W.J.; Nuñez-Moral, M.; Soler-Majoral, J.; Graterol Torres, F.; Ara, J.; et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice: Seeing Beyond the Numbers. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243196

Garcia-Lahosa A, Moreno-Millán S, Sanchez-García MC, Sanchez-Cardenas M, Steiss C, Escobar WJ, Nuñez-Moral M, Soler-Majoral J, Graterol Torres F, Ara J, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice: Seeing Beyond the Numbers. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243196

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Lahosa, Antoni, Sergio Moreno-Millán, Maria Cruz Sanchez-García, Miguel Sanchez-Cardenas, Christiane Steiss, Wilmer Jim Escobar, Miguel Nuñez-Moral, Jordi Soler-Majoral, Fredzzia Graterol Torres, Jordi Ara, and et al. 2025. "Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice: Seeing Beyond the Numbers" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243196

APA StyleGarcia-Lahosa, A., Moreno-Millán, S., Sanchez-García, M. C., Sanchez-Cardenas, M., Steiss, C., Escobar, W. J., Nuñez-Moral, M., Soler-Majoral, J., Graterol Torres, F., Ara, J., Bover, J., Sánchez-Alvarez, J. E., Husain-Syed, F., Koratala, A., Romero-González, G., Fernández-Delgado, S., Rodríguez-Chitiva, N., & Marcos-Ballesteros, E. (2025). Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in Advanced Nephrology Nursing Practice: Seeing Beyond the Numbers. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243196