Spinal Cord Stimulation Real-World Outcomes: A 24-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Trial Stimulation, Implantation, and Device Management

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Count | Mean | SD | p-Value Relative to Baseline | p-Value Relative to Previous Timepoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

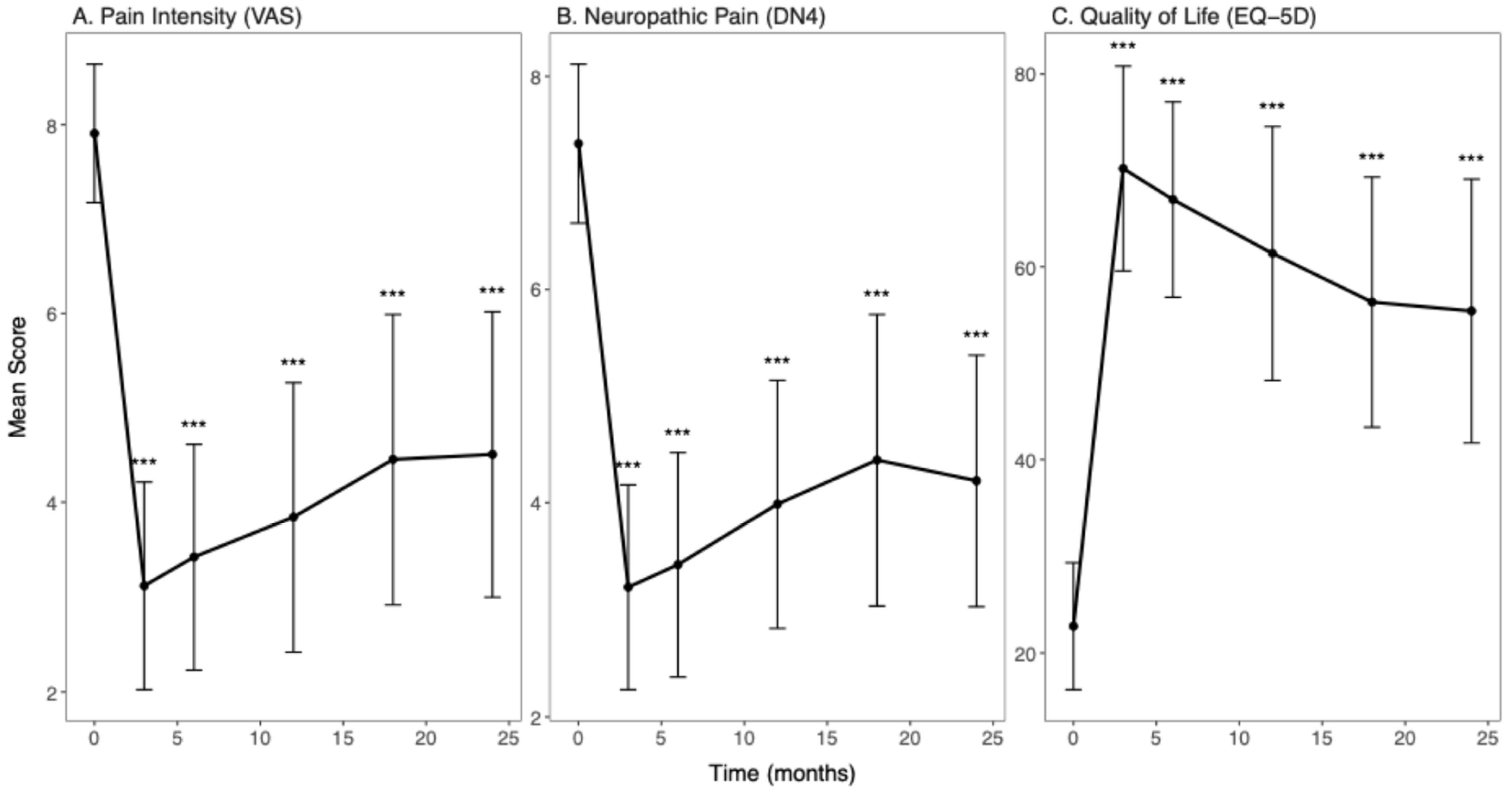

| VAS | |||||

| Baseline | 76 | 7.91 | 0.73 | -- | -- |

| 3 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.12 | 1.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.42 | 1.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 12 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.84 | 1.42 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 18 months post-procedure | 75 | 4.45 | 1.54 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 24 months post-procedure | 73 | 4.51 | 1.51 | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| DN4 | |||||

| Baseline | 76 | 7.37 | 0.75 | -- | -- |

| 3 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.21 | 0.96 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.42 | 1.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 12 months post-procedure | 76 | 3.99 | 1.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 18 months post-procedure | 75 | 4.40 | 1.37 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 24 months post-procedure | 73 | 4.21 | 1.18 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| EQ-5D | |||||

| Baseline | 76 | 22.76 | 6.55 | -- | -- |

| 3 months post-procedure | 76 | 70.20 | 10.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6 months post-procedure | 76 | 66.97 | 10.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 12 months post-procedure | 76 | 61.38 | 13.18 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 18 months post-procedure | 75 | 56.33 | 12.98 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 24 months post-procedure | 73 | 55.41 | 13.69 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Model | AIC | BIC | LRT χ2 | LRT p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | ||||

| Linear time effect | 1902.60 | 1939.60 | ||

| Quadratic time effect | 1756.00 | 1797.10 | 148.65 | <0.001 *** |

| DN4 | ||||

| Linear time effect | 1769.80 | 1806.80 | ||

| Quadratic time effect | 1654.30 | 1695.50 | 117.47 | <0.001 *** |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Linear time effect | 3945.30 | 3982.30 | ||

| Quadratic time effect | 3802.60 | 3843.70 | 144.65 | <0.001 *** |

| Measure | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | ||||

| Intercept | 5.82 | 0.84 | 6.96 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, linear component | −9.01 | 1.55 | −5.83 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, quadratic component | 20.74 | 1.54 | 13.48 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender, Male | −0.02 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.942 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.09 | 0.280 |

| Comorbidities present | −0.09 | 0.26 | −0.34 | 0.735 |

| Previous spine surgery | −0.47 | 0.25 | −1.85 | 0.068 |

| Neuropathic pain type | −0.17 | 0.30 | −0.56 | 0.579 |

| DN4 | ||||

| Intercept | 4.93 | 0.70 | 7.07 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, linear component | −8.80 | 1.40 | −6.29 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, quadratic component | 16.33 | 1.39 | 11.72 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender, Male | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.907 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.42 | 0.675 |

| Comorbidities present | −0.17 | 0.22 | −0.80 | 0.427 |

| Previous spine surgery | −0.35 | 0.21 | −1.67 | 0.099 |

| Neuropathic pain type | −0.02 | 0.25 | −0.09 | 0.929 |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Intercept | 48.85 | 7.32 | 6.67 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, linear component | 81.34 | 15.15 | 5.37 | <0.001 *** |

| Time, quadratic component | −200.13 | 15.09 | −13.27 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender, Male | −0.54 | 2.20 | −0.25 | 0.806 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.728 |

| Comorbidities present | 1.49 | 2.29 | 0.65 | 0.516 |

| Previous spine surgery | 5.19 | 2.20 | 2.36 | 0.021 * |

| Neuropathic pain type | 2.21 | 2.67 | 0.83 | 0.410 |

References

- Palmer, N.; Guan, Z.; Chai, N.C. Spinal cord stimulation for failed back surgery syndrome—Patient selection considerations. Perioper. Pain Med. 2019, 6, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Karri, J.; Joshi, M.; Polson, G.; Agarwal, V.; Madan, A.; Ghosh, P. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain syndromes: A review of considerations in practice management. Pain Physician 2020, 23, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Celestin, J.; Edwards, R.R.; Jamison, R.N. Pretreatment psychosocial variables as predictors of outcomes following lumbar surgery and spinal cord stimulation: A systematic review and literature synthesis. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Bianco, G.; Papa, A.; Gazzerro, G.; Rispoli, M.; Tammaro, D.; Di Dato, M.T.; Vernuccio, F.; Schatman, M. Dorsal root ganglion stimulation for chronic postoperative pain following thoracic surgery: A pilot study. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2021, 24, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shealy, C.N.; Mortimer, J.T.; Reswick, J.B. Electrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal columns. Anesth. Analg. 1967, 46, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapural, L.; Yu, C.; Doust, M.W.; Gliner, B.E.; Vallejo, R.; Sitzman, B.T.; Amirdelfan, K.; Morgan, D.M.; Brown, L.L.; Yearwood, T.L.; et al. Novel 10-kHz high-frequency therapy (HF10 therapy) is superior to traditional low-frequency spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic back and leg pain: The SENZA-RCT randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhail, N.; Levy, R.M.; Deer, T.R.; Kapural, L.; Li, S.; Amirdelfan, K.; Hunter, C.W.; Rosen, S.M.; Costandi, S.J.; Falowski, S.M.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of closed-loop spinal cord stimulation to treat chronic back and leg pain (Evoke): A double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hecke, O.; Torrance, N.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhassira, D.; Lantéri-Minet, M.; Attal, N.; Laurent, B.; Touboul, C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain 2008, 136, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deer, T.R.; Mekhail, N.; Provenzano, D.; Pope, J.; Krames, E.; Leong, M.; Levy, R.M.; Abejon, D.; Buchser, E.; Burton, A.; et al. The Appropriate Use of Neurostimulation of the Spinal Cord and Peripheral Nervous System for the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Ischemic Diseases: The Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2014, 17, 515–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Taylor, R.S.; Jacques, L.; Eldabe, S.; Meglio, M.; Molet, J.; Thomson, S.; O’cAllaghan, J.; Eisenberg, E.; Milbouw, G.; et al. Spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: A multicentre randomised controlled trial in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Pain 2007, 132, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruccu, G.; Garcia-Larrea, L.; Hansson, P.; Keindl, M.; Lefaucheur, J.; Paulus, W.; Taylor, R.; Tronnier, V.; Truini, A.; Attal, N. EAN guidelines on central neurostimulation therapy in chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016, 23, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, R.H.; O’Connor, A.B.; Kent, J.; Mackey, S.C.; Raja, S.N.; Stacey, B.R.; Levy, R.M.; Backonja, M.; Baron, R.; Harke, H.; et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain 2013, 154, 2249–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Chronic Pain of Neuropathic or Ischaemic Origin. TA159. 2008. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta159 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Thomson, S.; Huygen, F.; Prangnell, S.; De Andrés, J.; Baranidharan, G.; Belaïd, H.; Berry, N.; Billet, B.; Cooil, J.; De Carolis, G.; et al. Appropriate referral and selection of patients with chronic pain for spinal cord stimulation: European consensus recommendations and e-health tool. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.; Huygen, F.; Prangnell, S.; Baranidharan, G.; Belaïd, H.; Billet, B.; Eldabe, S.; De Carolis, G.; Demartini, L.; Gatzinsky, K.; et al. Applicability and Validity of an e-Health Tool for the Appropriate Referral and Selection of Patients With Chronic Pain for Spinal Cord Stimulation: Results From a European Retrospective Study. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2023, 26, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Ryan, J.; O’Donnell, R.; Eldabe, S.; Kumar, K.; North, R.B. The Cost-effectiveness of Spinal Cord Stimulation in the Treatment of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Clin. J. Pain 2010, 26, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco, G.; Al-Kaisy, A.; Natoli, S.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Matis, G.; Papa, A.; Kapural, L.; Staats, P. Neuromodulation in chronic pain management: Addressing persistent doubts in spinal cord stimulation. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, E.; Duarte, R.V.; Mann, S.; Lawrenc, T.R.; Raphael, J.H. Analysis of psychological characteristics impacting spinal cord stimulation treatment outcomes: A prospective assessment. Pain Physician 2015, 18, E369–E377. [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz, P.; Fama, C.; Roth, S.; Haller, J.; Wilock, M.; Lange, S.; Pilitsis, J. Predictors of Spinal Cord Stimulation Success. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2015, 18, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, C.A.; Chen, N.; Prusik, J.; Kumar, V.; Wilock, M.; Roth, S.; Pilitsis, J.G. The Use of Preoperative Psychological Evaluations to Predict Spinal Cord Stimulation Success: Our Experience and a Review of the Literature. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2016, 19, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schug, S.A.; Lavand’homme, P.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.-D. IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. Pain 2019, 160, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christelis, N.; Simpson, B.; Russo, M.; Stanton-Hicks, M.; Barolat, G.; Thomson, S.; Schug, S.; Baron, R.; Buchser, E.; Carr, D.B.; et al. Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome: A Proposal for Failed Back Surgery Syndrome and ICD-11. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; Beaton, D.; Cleeland, C.S.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Ader, D.N.; et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J. Pain 2008, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, J.T.; Young, J.P.; LaMoreaux, L.; Werth, J.L.; Poole, R.M. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001, 94, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, A.S.; Neary, M.P.; Cella, D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldabe, S.; Nevitt, S.; Griffiths, S.; Gulve, A.; Thomson, S.; Baranidharan, G.; Houten, R.; Brookes, M.; Kansal, A.; Earle, J.; et al. Does a Screening Trial for Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients With Chronic Pain of Neuropathic Origin Have Clinical Utility (TRIAL-STIM)? 36-Month Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.H.; Chassin, M.R.; Fink, A.; Solomon, D.H.; Kosecoff, J.; Park, R.E. A Method for the Detailed Assessment of the Appropriateness of Medical Technologies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 1986, 2, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco, G.; Cascella, M.; Li, S.; Day, M.; Kapural, L.; Robinson, C.L.; Sinagra, E. Reliability, Accuracy, and Comprehensibility of AI-Based Responses to Common Patient Questions Regarding Spinal Cord Stimulation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B.D.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Cook, K.F.; Taub, C.J.; Roy, A.; Burns, J.W.; Sullivan, M.; Mackey, S.C. Development and Validation of a Daily Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J. Pain 2017, 18, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. S11), S240–S252. [Google Scholar]

- Migliore, A.; Gigliucci, G.; Moretti, A.; Pietrella, A.; Peresson, M.; Atzeni, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Bazzichi, L.; Liguori, S.; Iolascon, G. Cross cultural adaptation and validation of Italian version of the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs scale and pain DETECT questionnaire for the distinction between nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2021, 2021, 6623651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalone, L.; Cortesi, P.A.; Ciampichini, R.; Belisari, A.; D’Angiolella, L.S.; Cesana, G.; Mantovani, L.G. Italian population-based values of EQ-5D health states. Value Health 2013, 16, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. lme4 mixed-effects modelling. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total (N = 76) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, M (mean) | 67.31 (10.31) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 46 (60.5%) |

| Female | 30 (39.5%) |

| Chronic pain diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Chronic back and leg pain | 31 (40.8%) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 5 (6.6%) |

| Idiopathic pain syndrome | 1 (1.3%) |

| Neuropathic pain syndrome | 7 (9.2%) |

| Post-surgical pain syndrome | 32 (42.1%) |

| Previous spine surgery, n (%) | |

| Yes | 32 (42.1%) |

| No | 44 (57.9%) |

| Pain type, n (%) | |

| Mixed | 16 (21.1%) |

| Neuropathic | 60 (78.9%) |

| Baseline neuropathic pain medication *, n (%) Yes: 75 (98.7%) No: 1 (1.3%) | |

| Major comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 14 (18.4%) |

| Metabolic | 3 (3.9%) |

| Neurological | 5 (6.6%) |

| Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity | 4 (5.3%) |

| No comorbidities | 50 (65.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo Bianco, G.; Therond, A.; D’Angelo, F.P.; Kapural, L.; Diwan, S.; Li, S.; Christo, P.J.; Hasoon, J.; Deer, T.R.; Robinson, C.L. Spinal Cord Stimulation Real-World Outcomes: A 24-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243149

Lo Bianco G, Therond A, D’Angelo FP, Kapural L, Diwan S, Li S, Christo PJ, Hasoon J, Deer TR, Robinson CL. Spinal Cord Stimulation Real-World Outcomes: A 24-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo Bianco, Giuliano, Alexandra Therond, Francesco Paolo D’Angelo, Leonardo Kapural, Sudhir Diwan, Sean Li, Paul J. Christo, Jamal Hasoon, Timothy R. Deer, and Christopher L. Robinson. 2025. "Spinal Cord Stimulation Real-World Outcomes: A 24-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243149

APA StyleLo Bianco, G., Therond, A., D’Angelo, F. P., Kapural, L., Diwan, S., Li, S., Christo, P. J., Hasoon, J., Deer, T. R., & Robinson, C. L. (2025). Spinal Cord Stimulation Real-World Outcomes: A 24-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243149