The Influence of Long-Term Medications and Patient Conditions on CT Image Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Captopril Group: Adults ≥ 18 years receiving captopril 50 mg/day for ≥2 months.

- Albuterol Group: Adults ≥ 18 years receiving albuterol 10 mg/day for ≥2 months.

- Medication Control: Age- and sex-matched controls without chronic medications.

- Obesity Group: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (weight > 90 kg, height ≤ 170 cm).

- COPD Group: GOLD Stage II–III confirmed by spirometry (FEV1/FVC < 0.7).

- Comorbidity Control: Healthy adults (BMI 18–25 kg/m2, no respiratory disease).

2.1. Rationale for Medication Selection

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Image Reconstruction

2.2.2. Patient Preparation and Contrast Administration

2.3. Timing and Image Acquisition

2.4. Reproducibility Assessment

2.5. Definition of Washout

2.6. Interobserver Reproducibility Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Compliance

2.9. Ethical Approval Statement

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Second Main Group (Condition Groups)

3.2. Results of Linear Mixed-Effects Modeling

- Treatment Groups (Captopril, Albuterol, Control)

- 2.

- Condition Groups (Obesity, COPD, Control)

3.3. Adjusted and Multivariable Analyses

4. Discussion

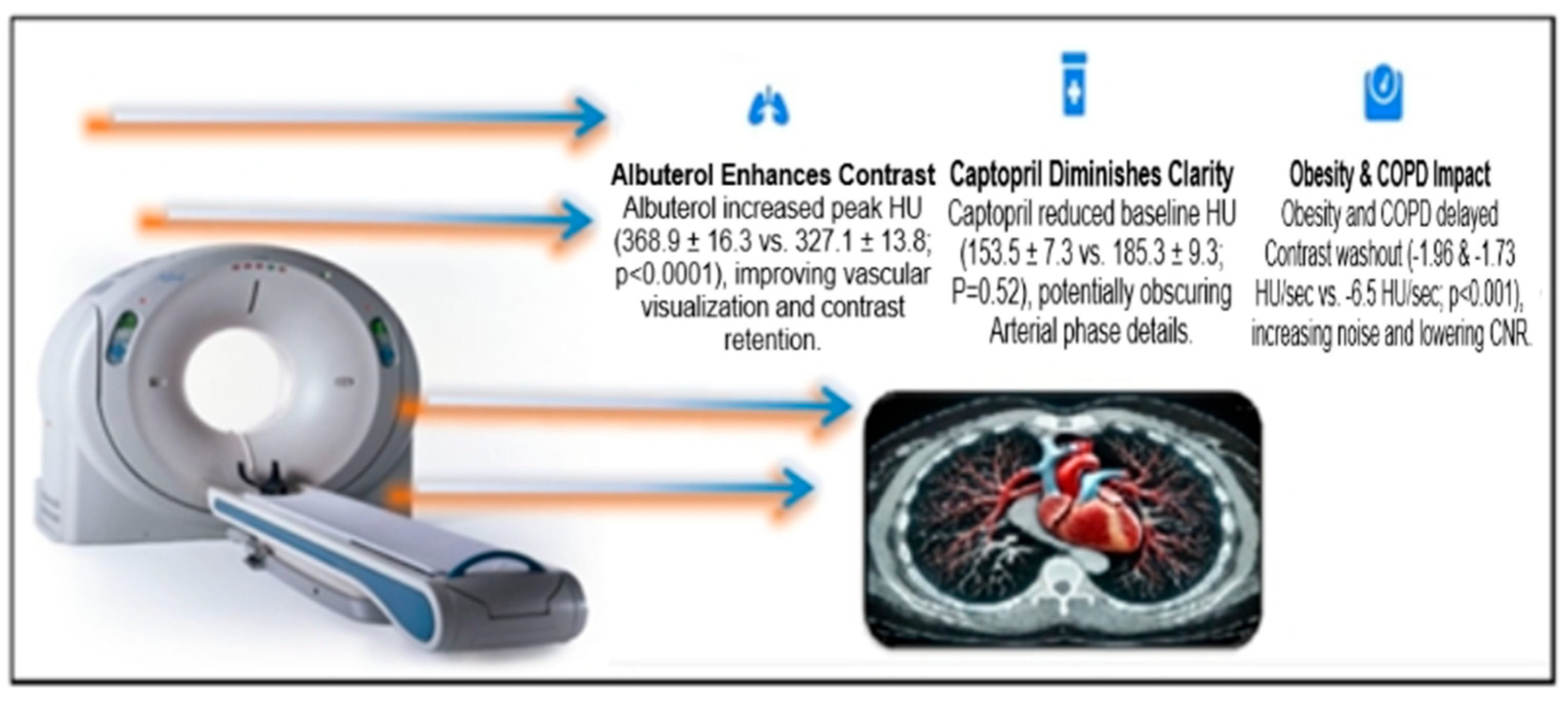

4.1. Pharmacological Effects on Contrast Enhancement

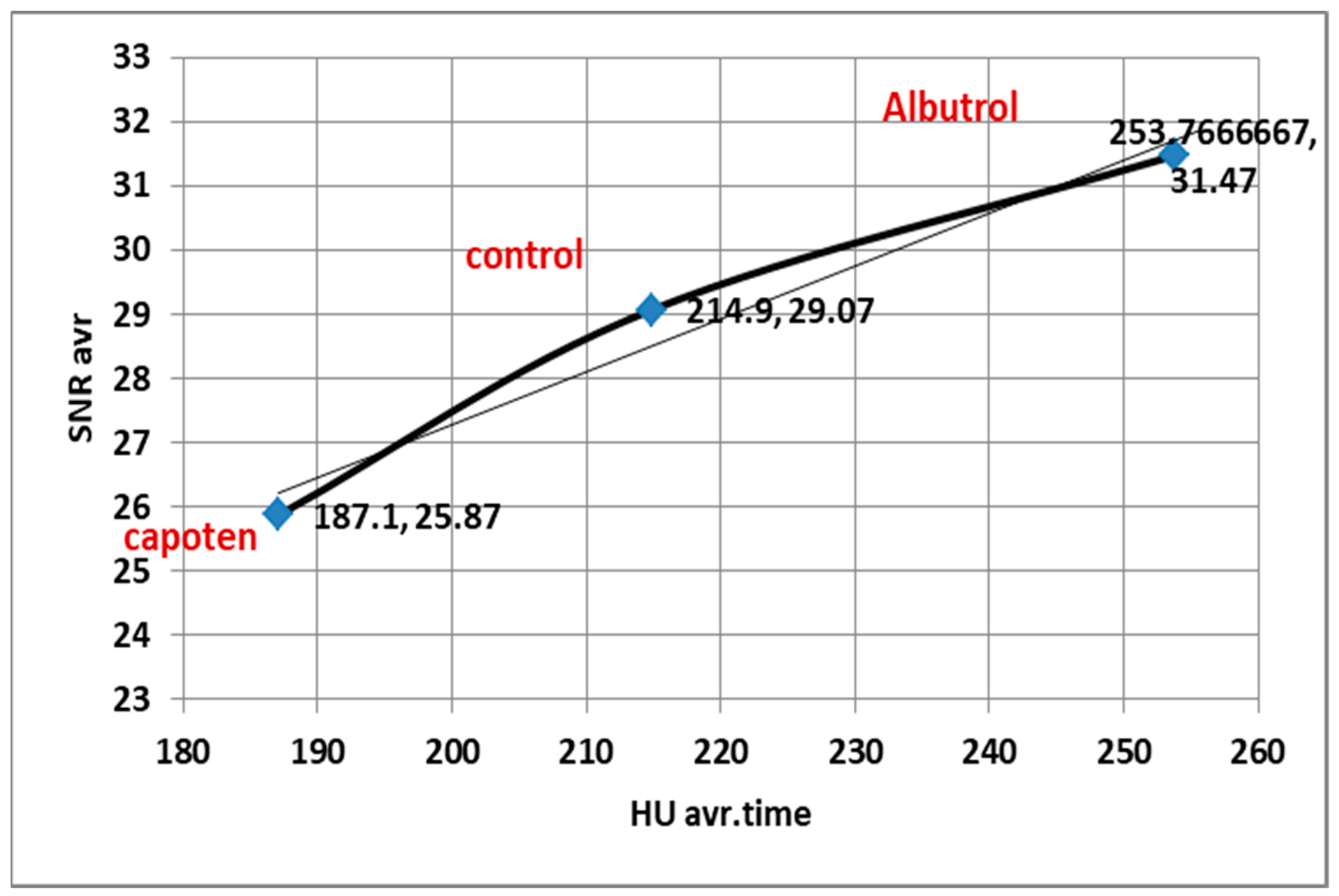

4.2. (SNR/CNR)

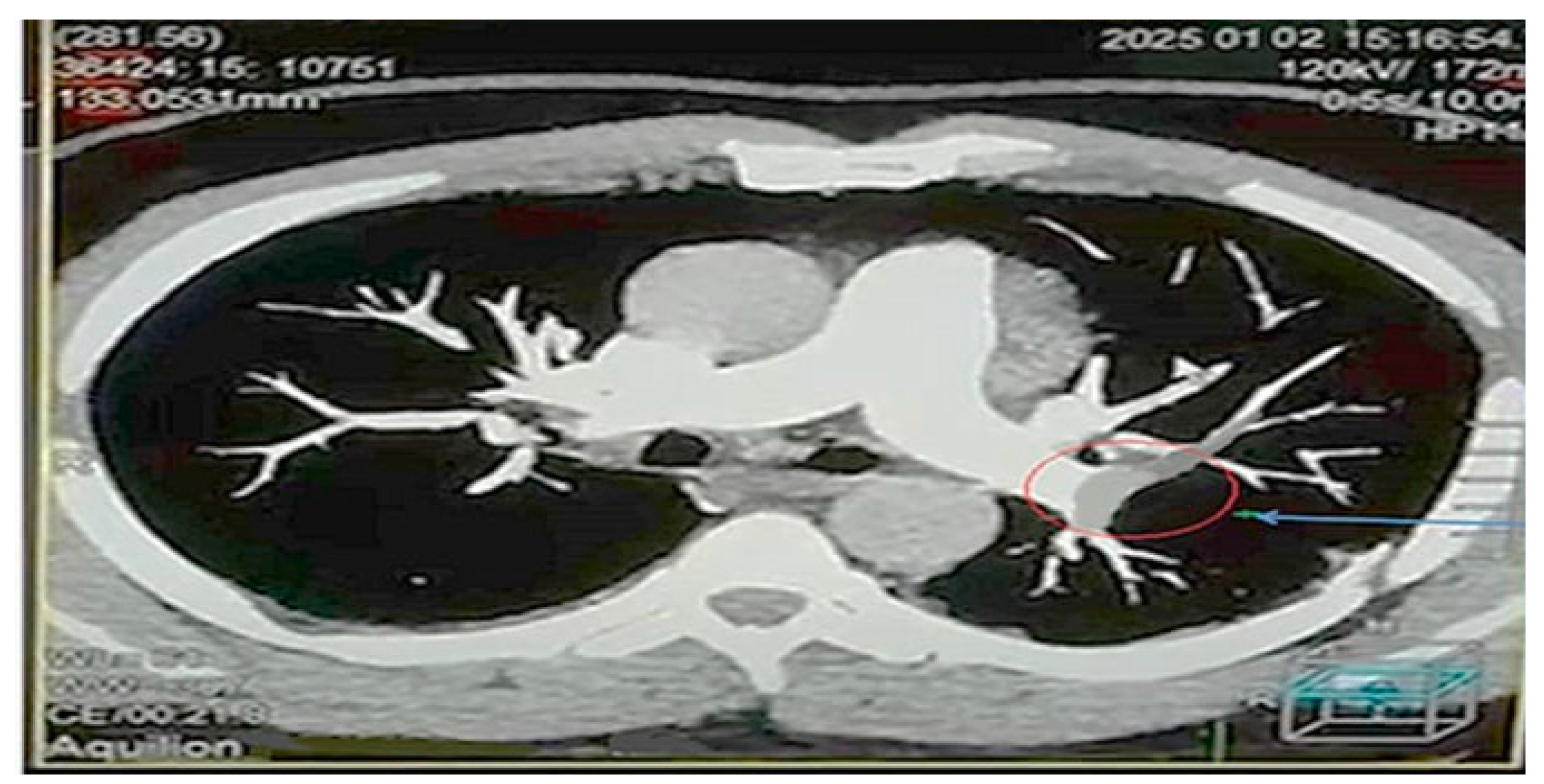

4.3. Influence of Chronic Comorbidities on Contrast Dynamics

4.4. Correlation Between HU, SNR, and CNR

4.5. Statistical Refinement and Model Adjustments

4.6. Visual Findings and Clinical Implications

4.7. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

- Protocol Adjustments: Imaging protocols should be adjusted to account for the effects of medications and medical conditions, such as modifying contrast timing, dosage, or using alternative imaging techniques.

- Personalized Care: Clinicians and radiologists must consider patient-specific factors when interpreting imaging results to reduce diagnostic errors and improve outcomes.

- Future Research: Further studies are needed to explore long-term effects, cost-effectiveness, and the impact of other chronic conditions and medications on CTPA image quality.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTPA | Computed tomography pulmonary angiography |

| HU | Hounsfield Unit |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| CNR | Contrast-to-noise ratio |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

References

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Torbicki, A.; Agnelli, G.; Danchin, N.; Fitzmaurice, D.; Galiè, N.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Kucher, N.; et al. ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 3033–3069, 3069a–3069k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Luo, C.; Ning, X.; Xiao, F.; Guan, K.; Tang, C.; Huang, F.; Liang, J.; Peng, P. Computed tomography image quality in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma: Intraindividual comparison of contrast agent concentrations. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1460505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemirani, H.; Pourrmoghaddas, M. A randomized trial of saline hydration to prevent contrast-induced nephropathy in patients on regular captopril or furosemide therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2012, 23, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, Y.N.V.; Obokata, M.; Koepp, K.E.; Egbe, A.C.; Wiley, B.; Borlaug, B.A. The β-Adrenergic Agonist Albuterol Improves Pulmonary Vascular Reserve in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M. Molecular mechanisms of β2-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, G.M.; Cicchiello, L.; Brink, J.; Huda, W. Patient size and radiation exposure in thoracic, pelvic, and abdominal CT examinations performed with automatic exposure control. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindera, S.T.; Nelson, R.C.; Mukundan, S., Jr.; Paulson, E.K.; Jaffe, T.A.; Miller, C.M.; DeLong, D.M.; Kawaji, K.; Yoshizumi, T.T.; Samei, E. Hypervascular Liver Tumors: Low Tube Voltage, High Tube Current Multi–Detector Row CT for Enhanced Detection—Phantom Study. Radiology 2008, 246, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaudon, M.; Latrabe, V.; Pariente, A.; Corneloup, O.; Begueret, H.; Laurent, F. Factors influencing accuracy of CT-guided percutaneous biopsies of pulmonary lesions. Eur. Radiol. 2004, 14, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Karwoski, R.A.; Gierada, D.S.; Bartholmai, B.J.; Koo, C.W. Quantitative CT Analysis of Diffuse Lung Disease. Radiographics 2020, 40, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.T. Intravenous contrast medium administration and scan timing at CT: Considerations and approaches. Radiology 2010, 256, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y.; Koyama, H.; Lee, H.Y.; Miura, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sugimura, K. Contrast-enhanced CT- and MRI-based perfusion assessment for pulmonary diseases: Basics and clinical applications. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 22, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, V.; Hon, M.; Haramati, L.B.; Gour, A.; Spiegler, P.; Bhalla, S.; Katz, D.S. Imaging of suspected pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in obese patients. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagomarsino, E.; Orellana, P.; Muñoz, J.; Velásquez, C.; Cavagnaro, F.; Valdés, F. Captopril scintigraphy in the study of arterial hypertension in pediatrics. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2004, 19, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.-C.; Chang, H.-W.; Liu, K.-L.; Lin, Y.-H.; Chueh, S.-C.; Lin, W.-C.; Ho, Y.-L.; Huang, J.-W.; Chiang, C.-K.; Yang, S.-Y.; et al. Primary aldosteronism: Diagnostic accuracy of the losartan and captopril tests. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppot, R.N.; Sahani, D.V.; Hahn, P.F.; Gervais, D.; Mueller, P.R. Impact of obesity on medical imaging and image-guided intervention. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Y.; Ohno, Y.; Nagata, H.; Tamokami, K.; Nishikimi, K.; Oshima, Y.; Hamabuchi, N.; Matsuyama, T.; Ueda, T.; Toyama, H. Advances for Pulmonary Functional Imaging: Dual-Energy Computed Tomography for Pulmonary Functional Imaging. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.A.; Zenkova, M.A.; Sen’kova, A.V. Bronchial Asthma, Airway Remodeling and Lung Fibrosis as Successive Steps of One Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, M.; Nasuhara, Y.; Onodera, Y.; Makita, H.; Nagai, K.; Fuke, S.; Ito, Y.; Betsuyaku, T.; Nishimura, M. Airflow limitation and airway dimensions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahos, I.; Jacobsen, M.C.; Godoy, M.C.; Stefanidis, K.; Layman, R.R. Dual-energy CT in pulmonary vascular disease. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20210699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisselink, H.J.; Pelgrim, G.J.; Rook, M.; Imkamp, K.; van Ooijen, P.M.A.; van den Berge, M.; de Bock, G.H.; Vliegenthart, R. Ultra-low-dose CT combined with noise reduction techniques for quantification of emphysema in COPD patients: An intra-individual comparison study with standard-dose CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 138, 109646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S. Challenges in imaging the obese patients. Ser. Clin. Med. Case Rep. Rev. 2023, 1, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.A.; Stoll, S.; Melzig, C.; Steuwe, A.; Partovi, S.; Böckler, D.; Kauczor, H.U.; Rengier, F. Prospective Study of Low-Radiation and Low-Iodine Dose Aortic CT Angiography in Obese and Non-Obese Patients: Image Quality and Impact of Patient Characteristics. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, L.-P.; Lemière, C.; Archambault, F.; Carrier, G.; Descary, M.C.; Deschesnes, F. Smoking and Asthma: Clinical and Radiologic Features, Lung Function, and Airway Inflammation. Chest 2006, 129, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffier, J.; Villani, N.; Defez, D.; Dabli, D.; Si-Mohamed, S. Spectral CT imaging: Technical principles of dual-energy CT and multi-energy photon-counting CT. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2023, 104, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Hobohm, L.; Ebner, M.; Kresoja, K.-P.; Münzel, T.; Konstantinides, S.V.; Lankeit, M. Trends in thrombolytic treatment and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism in Germany. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraev, T.P.; Omari, A.; Rushworth, R.L. Trends in pulmonary embolism morbidity and mortality in Australia. Thromb. Res. 2013, 132, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Dou, Y.; Dang, S.; Yu, N.; Guo, Y.; Han, D.; Jin, C. Effect of adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction-V algorithm and deep learning image reconstruction algorithm on image quality and emphysema quantification in COPD patients under ultra-low-dose conditions. Br. J. Radiol. 2025, 98, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Koyama, H.; Ohno, Y.; Negi, N.; Seki, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sugimura, K. Emphysema Quantification Using Ultralow-Dose CT With Iterative Reconstruction and Filtered Back Projection. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2016, 206, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, A.; Yanagawa, M.; Kikuchi, N.; Honda, O.; Tomiyama, N. Pulmonary Emphysema Quantification on Ultra-Low-Dose Computed Tomography Using Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction With or Without Lung Setting. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2018, 42, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerli, M.; Ottilinger, T.; Warschkow, R.; Leschka, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Wildermuth, S.; Bauer, R.W. Emphysema quantification and lung volumetry in chest X-ray equivalent ultralow dose CT—Intra-individual comparison with standard dose CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Group 1: Drug Effect (n = 45) | Group 2: Patient Condition (n = 45) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup 1: Captopril (n = 15) | Subgroup 2: Albuterol (n = 15) | Subgroup 3: Control (n = 15) | Subgroup 1: Obesity (n = 15) | Subgroup 2: COPD (n = 15) | Subgroup 3: Control (n = 15) | ||

| Age (years) | 30–65 | 30–65 | 30–65 | 30–65 | 30–65 | 30–65 | 0.87 (NS) |

| Weight (kg) | 70–90 | 70–90 | 70–90 | 70–90 | >90 | 70–90 | <0.01 (S) |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.72 (NS) | ||||||

| Male | 9 (60%) | 8 (53%) | 10 (67%) | 7 (47%) | 9 (60%) | 8 (53%) | |

| Female | 6 (40%) | 7 (47%) | 5 (33%) | 8 (53%) | 6 (40%) | 7 (47%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 28.4 ± 3.1 | 27.9 ± 2.8 | 29.1 ± 3.5 | 34.6 ± 4.2 | 26.5 ± 3.7 | 28.3 ± 3.0 | <0.001 (S) |

| FEV1 (% predicted), mean ± SD | - | - | - | 82.5 ± 15.3 | 58.4 ± 12.7 | 89.2 ± 10.5 | <0.001 (S) |

| Hypertension (Yes/No) | Yes (No Diabetes) | No (No Diabetes) | No (No Diabetes) | No | No | No | <0.001 (S) |

| Smokers, n (%) | <1% | <1% | <1% | 1 (15%) (Males) | 1 (10%) (Males) | <1% | 0.03 (S) |

| (a) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 153.5 ± 7.3 | 154 | 144 | 164 | 20 |

| 30 s | 288.9 ± 13.2 | 290 | 270 | 311 | 41 |

| 60 s | 118.9 ± 5.6 | 119 | 109 | 127 | 18 |

| (b) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 225.5 ± 15.1 | 228 | 196 | 240 | 44 |

| 30 s | 368.9 ± 16.3 | 370 | 343 | 395 | 52 |

| 60 s | 166.9 ± 10.3 | 169 | 148 | 183 | 35 |

| (c) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 185.3 ± 9.3 | 180 | 174 | 200 | 26 |

| 30 s | 327.1 ± 13.8 | 325 | 306 | 350 | 44 |

| 60 s | 132.3 ± 9.8 | 130 | 115 | 152 | 37 |

| (a) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 153.5 (148.2–158.8) | — | Initial contrast distribution. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 288.9 (280.1–297.7) | <0.001 | Reflects maximum contrast concentration. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −5.7 (−6.2–−5.2) | <0.001 | Rapid decline post-peak. |

| Total AUC (Area Under the Curve) | 4266.5 HU·s | — | Total contrast exposure over 60 s. |

| (b) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 225.5 (217.1–233.9) | — | Initial contrast distribution phase. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 368.9 (359.9–377.9) | <0.0001 | Maximum contrast concentration in the pulmonary artery. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −6.7 (−7.1 to −6.3) | <0.0001 | Rapid decline post-peak (~58% reduction by 60 s). |

| Total AUC (Area Under the Curve) | 11,890 HU·s | — | Total contrast exposure over 60 s. |

| (c) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 185.3 (179.9–190.7) | — | Initial contrast distribution phase. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 327.1 (319.2–335.0) | <0.0001 | Maximum contrast concentration in the pulmonary artery. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −6.5 (−6.9 to −6.1) | <0.0001 | Rapid post-peak decline (~59% reduction). |

| Total AUC (Area Under the Curve) | 12,015 HU·s | — | 12,015 HU·s |

| (a) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 139.0 ± 3.9 | 140 | 129 | 145 | 16 |

| 30 s | 239.1 ± 13.2 | 238 | 220 | 267 | 47 |

| 60 s | 180.5 ± 9.9 | 178 | 168 | 197 | 29 |

| (b) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 146.5 ± 8.0 | 145 | 132 | 158 | 26 |

| 30 s | 245.5 ± 10.2 | 248 | 226 | 260 | 34 |

| 60 s | 193.5 ± 9.9 | 193 | 176 | 210 | 34 |

| (c) | |||||

| Time (s) | Mean ± SD | Median | Min | Max | Range |

| 10 s | 216.7 ± 12.1 | 219 | 197 | 235 | 38 |

| 30 s | 310.3 ± 10.6 | 311 | 286 | 324 | 38 |

| 60 s | 118.7 ± 4.9 | 120 | 112 | 127 | 15 |

| (a) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 146.5 (142.1–150.9) | — | Initial contrast distribution phase. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 245.5 (239.8–251.1) | <0.0001 | Maximum contrast concentration in pulmonary artery. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −1.73 (−1.95–−1.51) | <0.0001 | Significant post-peak decline (~25% reduction). |

| Total AUC | 10.50 (10.32–10.68) | — | Total area under the contrast–time curve. |

| (b) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 139.0 (136.8–141.2) | — | Initial contrast distribution phase. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 239.1 (231.8–246.4) | <0.0001 | Maximum contrast concentration in pulmonary artery. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −1.96 (−2.24–−1.67) | <0.0001 | Significant post-peak decline (~21% reduction). |

| Total AUC | 10.00 (9.80–10.21) | — | Total area under the contrast–time curve. |

| (c) | |||

| Parameter | Estimate (CI 95%) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Baseline HU (10 s) | 216.7 (211.7–221.8) | — | Initial contrast distribution phase. |

| Peak HU (30 s) | 310.3 (305.2–315.3) | <0.0001 | Maximum contrast concentration in pulmonary artery. |

| Washout Rate (HU/s) | −6.39 HU/s (−5.62 to −7.1) | <0.0001 | Significant post-peak decline (~60% reduction). |

| Total AUC | 11.70 (11.49–11.91) | — | Total area under the contrast–time curve. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albweady, A. The Influence of Long-Term Medications and Patient Conditions on CT Image Quality. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243148

Albweady A. The Influence of Long-Term Medications and Patient Conditions on CT Image Quality. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243148

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbweady, Ali. 2025. "The Influence of Long-Term Medications and Patient Conditions on CT Image Quality" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243148

APA StyleAlbweady, A. (2025). The Influence of Long-Term Medications and Patient Conditions on CT Image Quality. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243148