Fetal Hepatic Circulation: From Vascular Physiology to Doppler Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

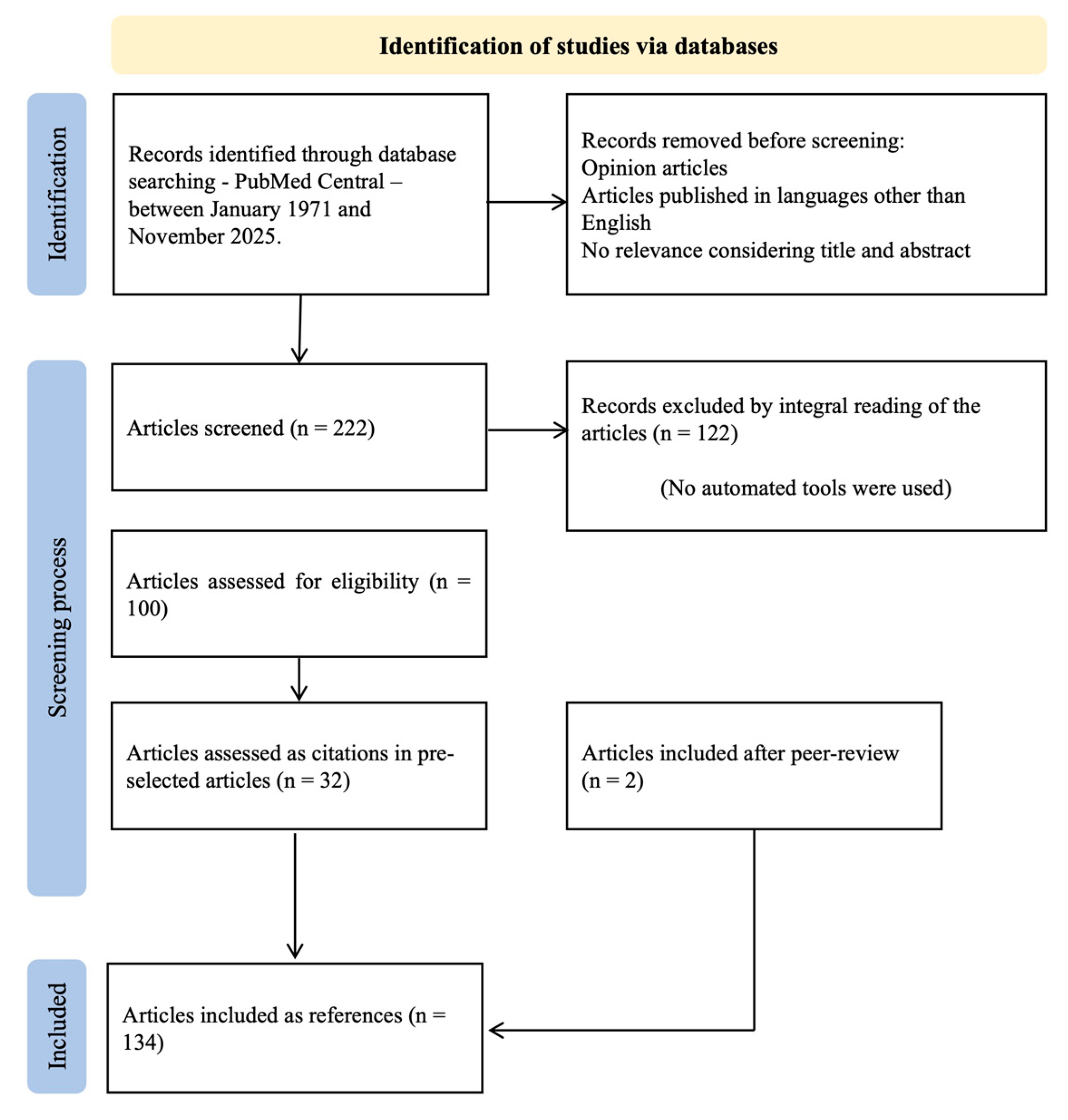

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Fetal Hepatic Circulation: Embryology and Anatomy

4. Microcirculation and Intrahepatic Flow Distribution

5. Hematopoietic Microenvironment in the Fetal Liver

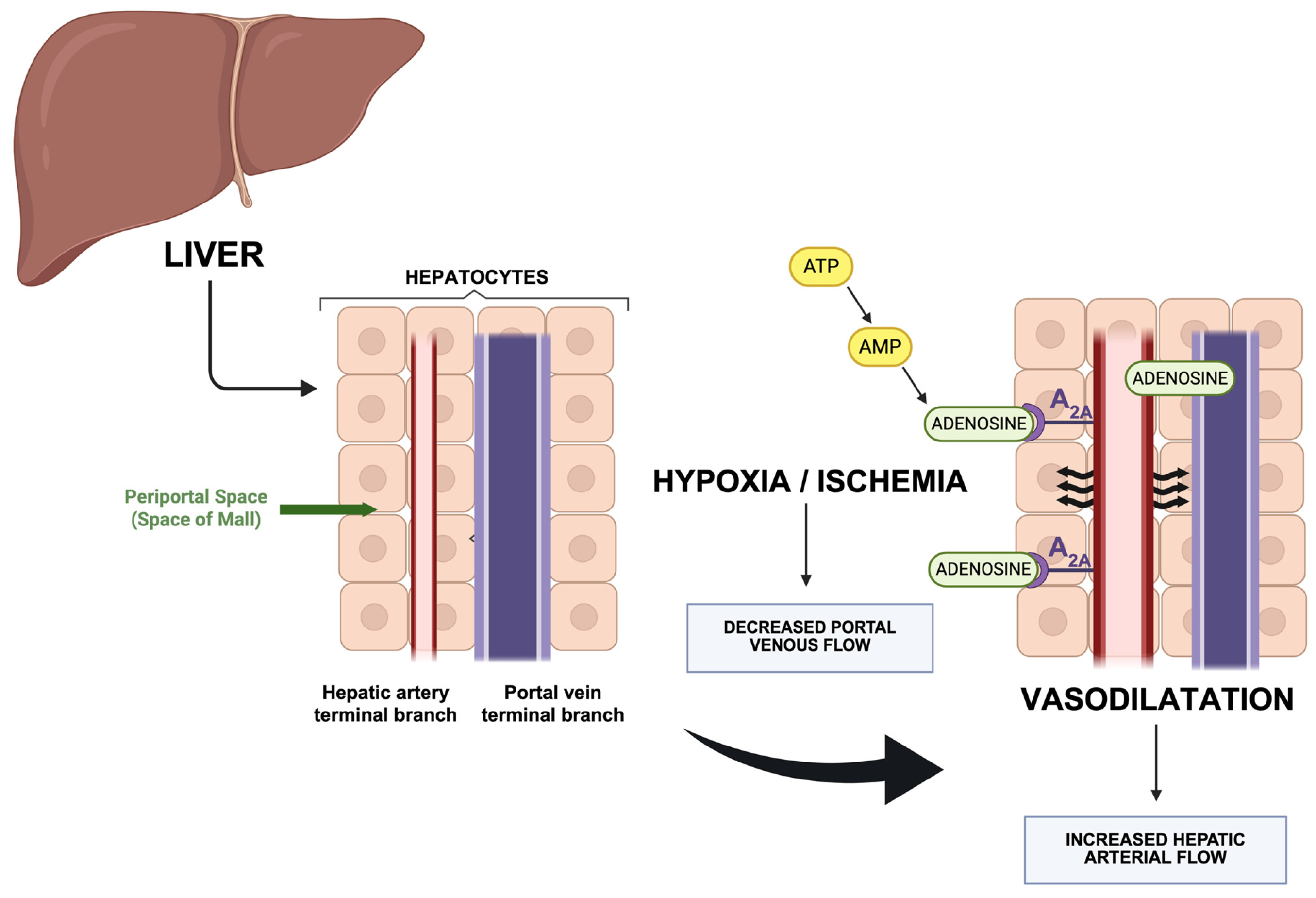

6. Hepatic Arterial and Venous Blood Flow Regulation

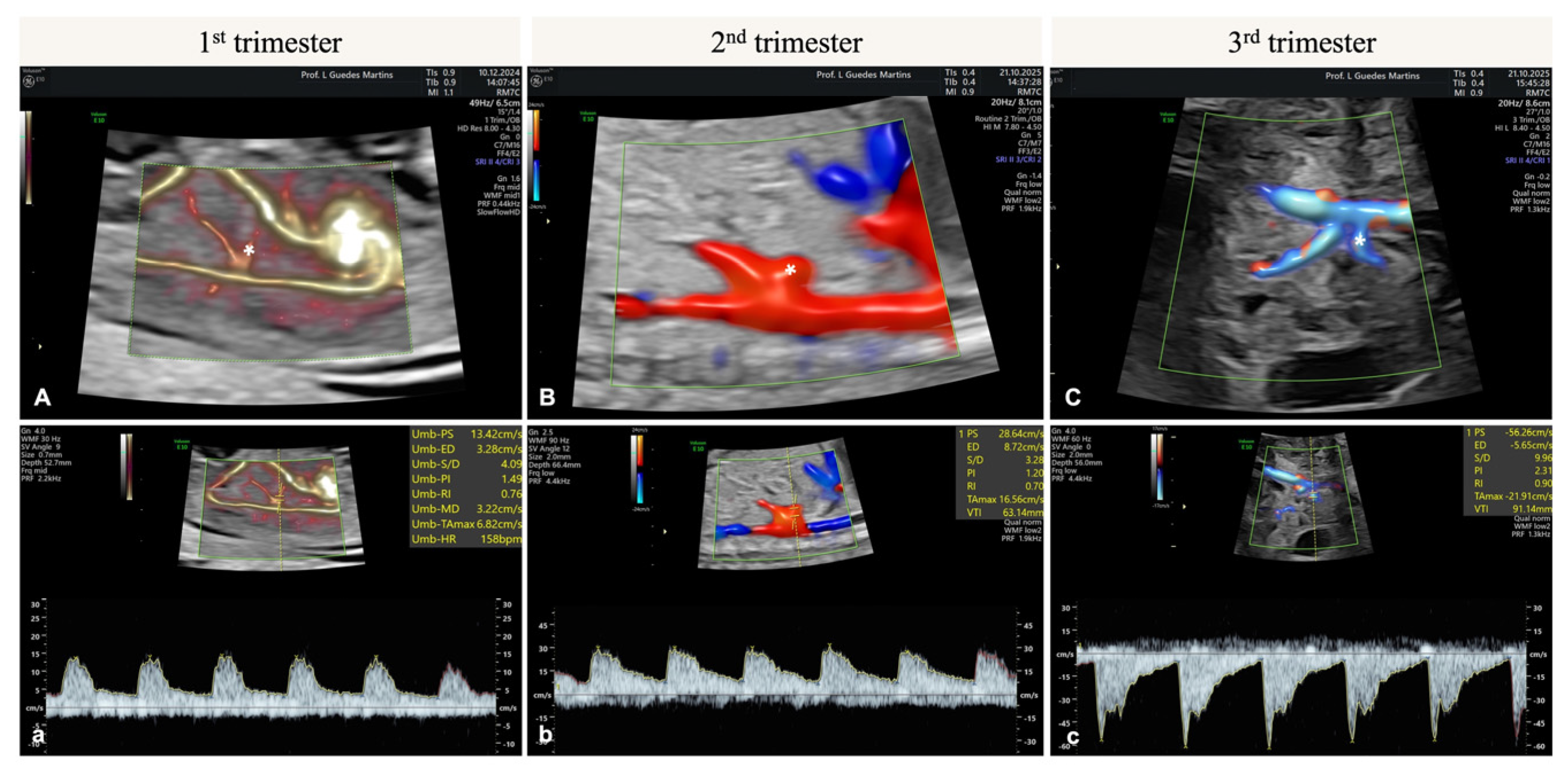

7. Hepatic Artery Doppler

8. Discussion

9. Future Research

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMP | Adenosine Monophosphate |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CHD | Congenital Heart Defect |

| DV | Ductus Venosus |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| FGR | Fetal Growth Restriction |

| HA | Hepatic Artery |

| HABR | Hepatic Arterial Buffer Response |

| HA-PI | Hepatic Artery Pulsatility Index |

| HSC | Hematopoietic Stem Cell |

| HSPC | Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell |

| IVC | Inferior Vena Cava |

| LSEC | Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell |

| MCA | Middle Cerebral Artery |

| PI | Pulsatility Index |

| PSV | Peak Systolic Velocity |

| PV | Portal Vein |

| RI | Resistance Index |

| SCF | Stem Cell Factor |

| SEC | Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| TTTS | Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome |

| UA | Umbilical Artery |

| UV | Umbilical Vein |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFR-2 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 |

References

- Collardeau-Frachon, S.; Scoazec, J.Y. Vascular development and differentiation during human liver organogenesis. Anat. Rec. 2008, 291, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancotti, A.; Monti, M.; Nevi, L.; Safarikia, S.; D’Ambrosio, V.; Brunelli, R.; Pajno, C.; Corno, S.; Di Donato, V.; Musella, A.; et al. Functions and the Emerging Role of the Foetal Liver into Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2019, 8, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si-Tayeb, K.; Lemaigre, F.P.; Duncan, S.A. Organogenesis and development of the liver. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagel, S.; Kivilevitch, Z.; Cohen, S.M.; Valsky, D.V.; Messing, B.; Shen, O.; Achiron, R. The fetal venous system, part I: Normal embryology, anatomy, hemodynamics, ultrasound evaluation and Doppler investigation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 35, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.B.; Morais, A.R.; Miguel, F.; Gaio, A.R.; Guedes-Martins, L. Fetal Aortic and Umbilical Doppler Flow Velocity Waveforms in Pregnancy: The Concept of Aortoumbilical Column. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 20, E101023222022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Crivellato, E. The development of the vascular system: A historical overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1214, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrides, E.; Moscoso, G.; Carvalho, J.S.; Campbell, S.; Thilaganathan, B. The anatomy of the umbilical, portal and hepatic venous systems in the human fetus at 14–19 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 18, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbing, C.; Rasmussen, S.; Godfrey, K.M.; Hanson, M.A.; Kiserud, T. Hepatic artery hemodynamics suggest operation of a buffer response in the human fetus. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 15, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbing, C.; Rasmussen, S.; Godfrey, K.M.; Hanson, M.A.; Kiserud, T. Redistribution pattern of fetal liver circulation in intrauterine growth restriction. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2009, 88, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zvanca, M.; Gielchinsky, Y.; Abdeljawad, F.; Bilardo, C.M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Hepatic artery Doppler in trisomy 21 and euploid fetuses at 11-13 weeks. Prenat. Diagn. 2011, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, H.T.; Cao, N.T.; Nguyen, P.N.; Truong Thi, L.G.; Le, M.T.; Nguyen Vu, Q.H. Umbilical cord coiling index in predicting neonatal outcomes: A single-center cross-sectional study from Vietnam. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025, 38, 2517763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, A.; Gomes, C.; Flack, N.; Montenegro, N.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for chromosomal abnormalities at 10-14 weeks: The role of ductus venosus blood flow. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 12, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiz, N.; Valencia, C.; Kagan, K.O.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Ductus venosus Doppler in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 and Turner syndrome at 11-13 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 33, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilavuz, O.; Vetter, K. Is the liver of the fetus the 4th preferential organ for arterial blood supply besides brain, heart, and adrenal glands? J. Perinat. Med. 1999, 27, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togrul, C.; Ozaksit, G.M.; Seckin, K.D.; Baser, E.; Karsli, M.F.; Gungor, T. Is there a role for fetal ductus venosus and hepatic artery Doppler in screening for fetal aneuploidy in the first trimester? J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 28, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuba, B.; Tousty, P.; Cnota, W.; Borowski, D.; Jagielska, A.; Dubiel, M.; Fuchs, A.; Fraszczyk-Tousty, M.; Dzidek, S.; Kajdy, A.; et al. First-Trimester Fetal Hepatic Artery Examination for Adverse Outcome Prediction. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.J.; Bernardeco, J.; Cohen, A.; Serrano, F. Hepatic arterial buffer response in monochorionic diamniotic pregnancies with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. J. Perinat. Med. 2023, 51, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Cruz, J.; Bernardeco, J.; Rijo, C.; Cohen, A.; Serrano, F. Hepatic arterial buffer response: Activation in donor fetuses and the effect of laser ablation of intertwin anastomosis. J. Perinat. Med. 2024, 52, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, T.T.; Asker, L.; Guven, H.K.; Kurt, G.Y.; Ulusoy, C.O.; Yilmaz, E.; Yilmaz, Z.V. Fetal Hepatic Artery Doppler in Pregnant Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2025, 53, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severn, C.B. A morphological study of the development of the human liver. I. Development of the hepatic diverticulum. Am. J. Anat. 1971, 131, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikspoors, J.; Peeters, M.; Mekonen, H.K.; Kruepunga, N.; Mommen, G.M.C.; Cornillie, P.; Kohler, S.E.; Lamers, W.H. The fate of the vitelline and umbilical veins during the development of the human liver. J. Anat. 2017, 231, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wen, H.; Liang, M.; Luo, D.; Zeng, Q.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ding, Y.; Wen, X.; Tan, Y.; et al. A new classification of congenital abnormalities of UPVS: Sonographic appearances, screening strategy and clinical significance. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. Langman’s Medical Embryology; Kluwer, W., Ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.L.; Persaud, T.V.N.; Torchia, M.G. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, 11th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, W. Human Embryology, 5th ed.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marty, M.; Lui, F. Embryology, Fetal Circulation. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537149 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Haugen, G.; Kiserud, T.; Godfrey, K.; Crozier, S.; Hanson, M. Portal and umbilical venous blood supply to the liver in the human fetus near term. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 24, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiserud, T.; Acharya, G. The fetal circulation. Prenat. Diagn. 2004, 24, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Choudhary, S.B. Isolated Absent Ductus Venosus with Intrahepatic Shunt: Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Fetal Med. 2014, 1, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautt, W.W.; Legare, D.J.; Ezzat, W.R. Quantitation of the hepatic arterial buffer response to graded changes in portal blood flow. Gastroenterology 1990, 98, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecher, K.; Campbell, S. Characteristics of fetal venous blood flow under normal circumstances and during fetal disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 7, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, B.K.; Khanna, G. Vascular Anomalies of the Pediatric Liver. Radiographics 2019, 39, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiserud, T. Physiology of the fetal circulation. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005, 10, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baschat, A.A.; Harman, C.R. Venous Doppler in the assessment of fetal cardiovascular status. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 18, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiserud, T.; Rasmussen, S.; Skulstad, S. Blood flow and the degree of shunting through the ductus venosus in the human fetus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 182 Pt 1, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiserud, T. Hemodynamics of the ductus venosus. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1999, 84, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivilevitch, Z.; Gilboa, Y.; Kassif, E.; Achiron, R. The Fetal Liver Afferent Venous Flow Volumes in Fetuses With Appropriate for Gestational Age Birth Weight. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seravalli, V.; Miller, J.L.; Block-Abraham, D.; Baschat, A.A. Ductus venosus Doppler in the assessment of fetal cardiovascular health: An updated practical approach. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2016, 95, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiserud, T.; Kessler, J.; Ebbing, C.; Rasmussen, S. Ductus venosus shunting in growth-restricted fetuses and the effect of umbilical circulatory compromise. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 28, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchirikov, M.; Rybakowski, C.; Huneke, B.; Schroder, H.J. Blood flow through the ductus venosus in singleton and multifetal pregnancies and in fetuses with intrauterine growth retardation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, M.; Pennati, G.; De Gasperi, C.; Bozzo, M.; Battaglia, F.C.; Ferrazzi, E. Simultaneous measurements of umbilical venous, fetal hepatic, and ductus venosus blood flow in growth-restricted human fetuses. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiserud, T. The ductus venosus. Semin. Perinatol. 2001, 25, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschat, A.A. Ductus venosus Doppler for fetal surveillance in high-risk pregnancies. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 53, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Martins, J.G.; Biggio, J.R.; Abuhamad, A. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #52: Diagnosis and management of fetal growth restriction: (Replaces Clinical Guideline Number 3, April 2012). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, B2–B17. [Google Scholar]

- Couvelard, A.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Dauge, M.C.; Bringuier, A.F.; Potet, F.; Feldmann, G. Structural and functional differentiation of sinusoidal endothelial cells during liver organogenesis in humans. Blood 1996, 87, 4568–4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouysse, G.; Couvelard, A.; Frachon, S.; Bouvier, R.; Nejjari, M.; Dauge, M.C.; Feldmann, G.; Henin, D.; Scoazec, J.Y. Relationship between vascular development and vascular differentiation during liver organogenesis in humans. J. Hepatol. 2002, 37, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Omori, Y.; Yoshioka, T.; Tokairin, T.; McCourt, P.; Enomoto, K. Involvement of signaling of VEGF and TGF-beta in differentiation of sinusoidal endothelial cells during culture of fetal rat liver cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2007, 329, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Sancho, J.; Marrone, G.; Fernandez-Iglesias, A. Hepatic microcirculation and mechanisms of portal hypertension. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, N.; Peto, K.; Magyar, Z.; Klarik, Z.; Varga, G.; Oltean, M.; Mantas, A.; Czigany, Z.; Tolba, R.H. Hemorheological and Microcirculatory Factors in Liver Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury-An Update on Pathophysiology, Molecular Mechanisms and Protective Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, T.J.; Cast, A.E.; Huppert, K.A.; Huppert, S.S. Epithelial VEGF signaling is required in the mouse liver for proper sinusoid endothelial cell identity and hepatocyte zonation in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014, 306, G849–G862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Y.; Takabe, Y.; Nakakura, T.; Tanaka, S.; Koike, T.; Shiojiri, N. Sinusoid development and morphogenesis may be stimulated by VEGF-Flk-1 signaling during fetal mouse liver development. Dev. Dyn. 2010, 239, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, L.; Cadamuro, M.; Libbrecht, L.; Raynaud, P.; Spirli, C.; Fiorotto, R.; Okolicsanyi, L.; Lemaigre, F.; Strazzabosco, M.; Roskams, T. Epithelial expression of angiogenic growth factors modulate arterial vasculogenesis in human liver development. Hepatology 2008, 47, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patan, S. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis as mechanisms of vascular network formation, growth and remodeling. J. Neurooncol. 2000, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchirikov, M.; Schroder, H.J.; Hecher, K. Ductus venosus shunting in the fetal venous circulation: Regulatory mechanisms, diagnostic methods and medical importance. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 27, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libretti, A.; Savasta, F.; Nicosia, A.; Corsini, C.; De Pedrini, A.; Leo, L.; Lagana, A.S.; Troia, L.; Dellino, M.; Tinelli, R.; et al. Exploring the Father’s Role in Determining Neonatal Birth Weight: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, M.; Pennati, G.; De Gasperi, C.; Battaglia, F.C.; Ferrazzi, E. Role of ductus venosus in distribution of umbilical blood flow in human fetuses during second half of pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 279, H1256–H1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurses, C.; Karadag, B.; Isenlik, B.S.T. Normal variants of ductus venosus spectral Doppler flow patterns in normal pregnancies. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.; Rasmussen, S.; Godfrey, K.; Hanson, M.; Kiserud, T. Fetal growth restriction is associated with prioritization of umbilical blood flow to the left hepatic lobe at the expense of the right lobe. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.; Rasmussen, S.; Godfrey, K.; Hanson, M.; Kiserud, T. Longitudinal study of umbilical and portal venous blood flow to the fetal liver: Low pregnancy weight gain is associated with preferential supply to the fetal left liver lobe. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 63, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennati, G.; Corno, C.; Costantino, M.L.; Bellotti, M. Umbilical flow distribution to the liver and the ductus venosus in human fetuses during gestation: An anatomy-based mathematical modeling. Med. Eng. Phys. 2003, 25, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, A.M. Hepatic and ductus venosus blood flows during fetal life. Hepatology 1983, 3, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiserud, T.; Stratford, L.; Hanson, M.A. Umbilical flow distribution to the liver and the ductus venosus: An in vitro investigation of the fluid dynamic mechanisms in the fetal sheep. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 177, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathanielsz, P.W.; Hanson, M.A. The fetal dilemma: Spare the brain and spoil the liver. J. Physiol. 2003, 548 Pt 2, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K.M.; Haugen, G.; Kiserud, T.; Inskip, H.M.; Cooper, C.; Harvey, N.C.; Crozier, S.R.; Robinson, S.M.; Davies, L. Southampton Women’s Survey Study Group; et al. Fetal liver blood flow distribution: Role in human developmental strategy to prioritize fat deposition versus brain development. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubiel, M.; Breborowicz, G.H.; Gudmundsson, S. Evaluation of fetal circulation redistribution in pregnancies with absent or reversed diastolic flow in the umbilical artery. Early Hum. Dev. 2003, 71, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giussani, D.A. The fetal brain sparing response to hypoxia: Physiological mechanisms. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, E.A.; Lemaigre, F.P. Development of the liver: Insights into organ and tissue morphogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotto, J.; Stephan, T.L.; Hoodless, P.A. Fetal liver development and implications for liver disease pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, I.L. Stem cells: Units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell 2000, 100, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.; Yoshimoto, M.; Takebe, T. Fetal liver hematopoiesis: From development to delivery. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-da-Silva, F.; Peixoto, M.; Cumano, A.; Pinto-do, O.P. Crosstalk Between the Hepatic and Hematopoietic Systems During Embryonic Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinhaus, B.; Homan, S.; Kincaid, M.; Tadwalkar, A.; Gu, X.; Kumar, S.; Slaughter, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Kofron, J.M.; et al. Differential regulation of fetal bone marrow and liver hematopoiesis by yolk-sac-derived myeloid cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriza, J.; Thompson, H.; Petrosian, R.; Manilay, J.O.; Garcia-Ojeda, M.E. The migration of hematopoietic progenitors from the fetal liver to the fetal bone marrow: Lessons learned and possible clinical applications. Exp. Hematol. 2013, 41, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahal, G.S.; Jauniaux, E.; Kinnon, C.; Thrasher, A.J.; Rodeck, C.H. Normal development of human fetal hematopoiesis between eight and seventeen weeks’ gestation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 183, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.M.; Botting, R.A.; Stephenson, E.; Green, K.; Webb, S.; Jardine, L.; Calderbank, E.F.; Polanski, K.; Goh, I.; Efremova, M.; et al. Decoding human fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nature 2019, 574, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, H.; Mehatre, S.H.; Khurana, S. The hematopoietic stem cell expansion niche in fetal liver: Current state of the art and the way forward. Exp. Hematol. 2024, 136, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomizo, T.; Ideue, T.; Morino-Koga, S.; Tham, C.Y.; Sato, T.; Takeda, N.; Kubota, Y.; Kurokawa, M.; Komatsu, N.; Ogawa, M.; et al. Independent origins of fetal liver haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nature 2022, 609, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, S.; Trumpp, A.; Milsom, M.D. Causes and Consequences of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Heterogeneity. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, E.; Gottgens, B. From haematopoietic stem cells to complex differentiation landscapes. Nature 2018, 553, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, G.M.; Jeffery, E.; Morrison, S.J. Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Paik, N.Y.; Sanborn, M.A.; Bandara, T.; Vijaykumar, A.; Sottoriva, K.; Rehman, J.; Nombela-Arrieta, C.; Pajcini, K.V. Hematopoietic Jagged1 is a fetal liver niche factor required for functional maturation and engraftment of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2210058120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. Stem cells and niches: Mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 2008, 132, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita Peixoto, M.; Soares-da-Silva, F.; Bonnet, V.; Zhou, Y.; Ronteix, G.; Santos, R.F.; Mailhe, M.P.; Nogueira, G.; Feng, X.; Pereira, J.P.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of fetal liver hematopoietic niches. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20240592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, P.S.; Lee, K.H.; Goerdt, S.; Augustin, H.G. Angiodiversity and organotypic functions of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, D.; Kulkeaw, K.; Mizuochi, C.; Horio, Y.; Okayama, S. Hepatoblasts comprise a niche for fetal liver erythropoiesis through cytokine production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 410, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J.A.; Mendelson, A.; Kunisaki, Y.; Birbrair, A.; Kou, Y.; Arnal-Estape, A.; Pinho, S.; Ciero, P.; Nakahara, F.; Ma’ayan, A.; et al. Fetal liver hematopoietic stem cell niches associate with portal vessels. Science 2016, 351, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayvanjoo, A.H.; Splichalova, I.; Bejarano, D.A.; Huang, H.; Mauel, K.; Makdissi, N.; Heider, D.; Tew, H.M.; Balzer, N.R.; Greto, E.; et al. Fetal liver macrophages contribute to the hematopoietic stem cell niche by controlling granulopoiesis. Elife 2024, 13, e86493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagraoui, J.; Lepage-Noll, A.; Anjo, A.; Uzan, G.; Charbord, P. Fetal liver stroma consists of cells in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Blood 2003, 101, 2973–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.A.; Bhatia, M. Analysis of the human fetal liver hematopoietic microenvironment. Stem Cells Dev. 2005, 14, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, F. Fetal liver: An ideal niche for hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanni, D.; Angotzi, F.; Lai, F.; Gerosa, C.; Senes, G.; Fanos, V.; Faa, G. Four stages of hepatic hematopoiesis in human embryos and fetuses. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 31, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetto, D.A.; Singal, A.K.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Caldwell, S.H.; Ahn, J.; Kamath, P.S. ACG Clinical Guideline: Disorders of the Hepatic and Mesenteric Circulation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eipel, C.; Abshagen, K.; Vollmar, B. Regulation of hepatic blood flow: The hepatic arterial buffer response revisited. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 6046–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaggiari, M.; Martinino, A.; Ray, C.E., Jr.; Bencini, G.; Petrochenkov, E.; Di Cocco, P.; Almario-Alvarez, J.; Tzvetanov, I.; Benedetti, E. Hepatic Arterial Buffer Response in Liver Transplant Recipients: Implications and Treatment Options. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 40, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwiebel, W.J.; Mountford, R.A.; Halliwell, M.J.; Wells, P.N. Splanchnic blood flow in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Investigation with duplex Doppler US. Radiology 1995, 194, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautt, W.W. Regulatory processes interacting to maintain hepatic blood flow constancy: Vascular compliance, hepatic arterial buffer response, hepatorenal reflex, liver regeneration, escape from vasoconstriction. Hepatol. Res. 2007, 37, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautt, W.W. Mechanism and role of intrinsic regulation of hepatic arterial blood flow: Hepatic arterial buffer response. Am. J. Physiol. 1985, 249 Pt 1, G549–G556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, M.T.; Nayeem, M.A. The Role of Adenosine A(2A) Receptor, CYP450s, and PPARs in the Regulation of Vascular Tone. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1720920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathie, R.T.; Alexander, B. The role of adenosine in the hyperaemic response of the hepatic artery to portal vein occlusion (the ‘buffer response’). Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 100, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Cox, H.A.; Koupenova, M.; Ravid, K. A2 adenosine receptors and vascular pathologies. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Shiba, H.; Fung, J.J.; Wang, L.F.; Arakawa, Y.; Irefin, S.; Demetris, A.J.; Kelly, D.M. The role of the A2a receptor agonist, regadenoson, in modulating hepatic artery flow in the porcine small-for-size liver graft. J. Surg. Res. 2012, 174, e37–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guieu, R.; Deharo, J.C.; Maille, B.; Crotti, L.; Torresani, E.; Brignole, M.; Parati, G. Adenosine and the Cardiovascular System: The Good and the Bad. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.F.; Rose’Meyer, R.B. Vascular adenosine receptors; potential clinical applications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 11, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Zhou, D.; Qian, X.; Luan, J.; Lv, X. The role of the CD39-CD73-adenosine pathway in liver disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camici, M.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Tozzi, M.G. The Inside Story of Adenosine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiringhelli, F.; Bruchard, M.; Chalmin, F.; Rebe, C. Production of adenosine by ectonucleotidases: A key factor in tumor immunoescape. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 473712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, M.; Thonig, A.; Pohl, S.; Ripoll, C.; Zipprich, A. Hepatic arterial vasodilation is independent of portal hypertension in early stages of cirrhosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opheim, G.L.; Moe Holme, A.; Blomhoff Holm, M.; Melbye Michelsen, T.; Muneer Zahid, S.; Paasche Roland, M.C.; Henriksen, T.; Haugen, G. The impact of umbilical vein blood flow and glucose concentration on blood flow distribution to the fetal liver and systemic organs in healthy pregnancies. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 12481–12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzi, E.; Lees, C.; Acharya, G. The controversial role of the ductus venosus in hypoxic human fetuses. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchirikov, M.; Kertschanska, S.; Sturenberg, H.J.; Schroder, H.J. Liver blood perfusion as a possible instrument for fetal growth regulation. Placenta 2002, 23 (Suppl. A), S153–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammert, E.; Cleaver, O.; Melton, D. Role of endothelial cells in early pancreas and liver development. Mech. Dev. 2003, 120, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilardo, C.M.; Timmerman, E.; De Medina, P.G.; Clur, S.A. Low-resistance hepatic artery flow in first-trimester fetuses: An ominous sign. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 37, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Roman, C.; Rudolph, A.M. Effects of reducing uterine blood flow on fetal blood flow distribution and oxygen delivery. J. Dev. Physiol. 1991, 15, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zvanca, M.; Vladareanu, R. Liver Vascularity and Function in Fetuses with Trisomy 21. Donald Sch. J. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 6, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis, G.; Akolekar, R.; Sarquis, R.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Prediction of small-for-gestation neonates from biophysical and biochemical markers at 11–13 weeks. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2011, 29, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Wright, D.; Valencia, C.; Maiz, N.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency, fetal heart rate, free beta-hCG and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Rolnik, D.L.; O’Gorman, N.; Delgado, J.L.; Akolekar, R.; Konstantinidou, L.; Tsavdaridou, M.; Galeva, S.; et al. Screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Spencer, K.; Avgidou, K.; Faiola, S.; Falcon, O. Multicenter study of first-trimester screening for trisomy 21 in 75,821 pregnancies: Results and estimation of the potential impact of individual risk-orientated two-stage first-trimester screening. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 25, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijders, R.J.; Noble, P.; Sebire, N.; Souka, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Fetal Medicine Foundation First Trimester Screening Group. Lancet 1998, 352, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoui, R.; Heling, K.S.; Karl, K. Ultrasound of the fetal veins part 1: The intrahepatic venous system. Ultraschall Med. 2014, 35, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhide, A.; Acharya, G.; Baschat, A.; Bilardo, C.M.; Brezinka, C.; Cafici, D.; Ebbing, C.; Hernandez-Andrade, E.; Kalache, K.; Kingdom, J.; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): Use of Doppler velocimetry in obstetrics. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 58, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, L.; Khati, N.J.; Deshmukh, S.P.; Dudiak, K.M.; Harisinghani, M.G.; Henrichsen, T.L.; Meyer, B.J.; Nyberg, D.A.; Poder, L.; Shipp, T.D.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Assessment of Fetal Well-Being. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2016, 13 Pt A, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Giraldo, S.; Alfonso Ayala, D.A.; Arreaza Graterol, M.; Perez Olivo, J.L.; Solano Montero, A.F. Three-dimensional Doppler ultrasonography for the assessment of fetal liver vascularization in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019, 144, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boito, S.M.; Struijk, P.C.; Ursem, N.T.; Stijnen, T.; Wladimiroff, J.W. Assessment of fetal liver volume and umbilical venous volume flow in pregnancies complicated by insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. BJOG 2003, 110, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, A.; Ebbing, C.; Rasmussen, S.; Kiserud, T.; Hanson, M.; Kessler, J. Altered development of fetal liver perfusion in pregnancies with pregestational diabetes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Balaha, M.H.H.; Halwagy, A.E.S.E.; Namori, M.M.E. Fetal Liver Size, Hepatic Artery Doppler Study in Late Intra Uterine Growth Restriction. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2021, 33, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.M.; Hsu, K.F.; Ko, H.C.; Yao, B.L.; Chang, C.H.; Yu, C.H.; Chen, H.Y. Three-dimensional ultrasound assessment of fetal liver volume in normal pregnancy: A comparison of reproducibility with two-dimensional ultrasound and a search for a volume constant. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1997, 23, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Yu, C.H.; Ko, H.C.; Chang, F.M.; Chen, H.Y. Assessment of normal fetal liver blood flow using quantitative three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2003, 29, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Miller, R.S.; Miller, J.L.; Monson, M.A.; Porter, T.F.; Običan, S.G.; Simpson, L.L. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #72: Twin-twin transfusion syndrome and twin anemia-polycythemia sequence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, B16–B37. [Google Scholar]

- Frusca, T.; Todros, T.; Lees, C.; Bilardo, C.M.; Investigators, T. Outcome in early-onset fetal growth restriction is best combining computerized fetal heart rate analysis with ductus venosus Doppler: Insights from the Trial of Umbilical and Fetal Flow in Europe. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S783–S789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecher, K.; Bilardo, C.M.; Stigter, R.H.; Ville, Y.; Hackeloer, B.J.; Kok, H.J.; Senat, M.V.; Visser, G.H. Monitoring of fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction: A longitudinal study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 18, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications, C.; Berkley, E.; Chauhan, S.P.; Abuhamad, A. Doppler assessment of the fetus with intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Stampalija, T.; Dowswell, T. Fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high-risk pregnancies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD007529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, J.H.; Cafici, D. Fetal Doppler assessment in pregnancy. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 100, 102594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil-Santos, I.; Guedes-Martins, L. Fetal Hepatic Circulation: From Vascular Physiology to Doppler Assessment. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243147

Gil-Santos I, Guedes-Martins L. Fetal Hepatic Circulation: From Vascular Physiology to Doppler Assessment. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243147

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil-Santos, Inês, and Luís Guedes-Martins. 2025. "Fetal Hepatic Circulation: From Vascular Physiology to Doppler Assessment" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243147

APA StyleGil-Santos, I., & Guedes-Martins, L. (2025). Fetal Hepatic Circulation: From Vascular Physiology to Doppler Assessment. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243147