Multiparametric Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: Comparison with CAP and Robustness Across Breathing States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Patient Preparation and Examination Workflow

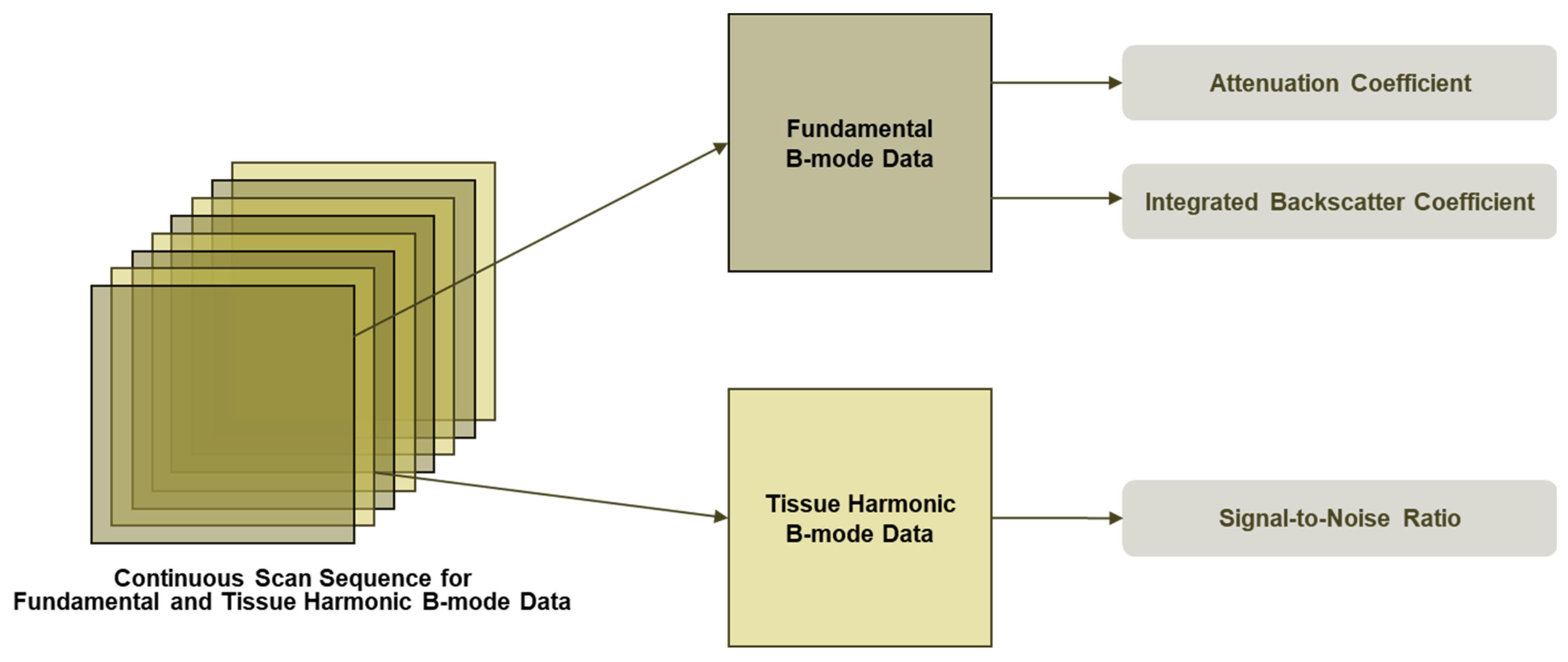

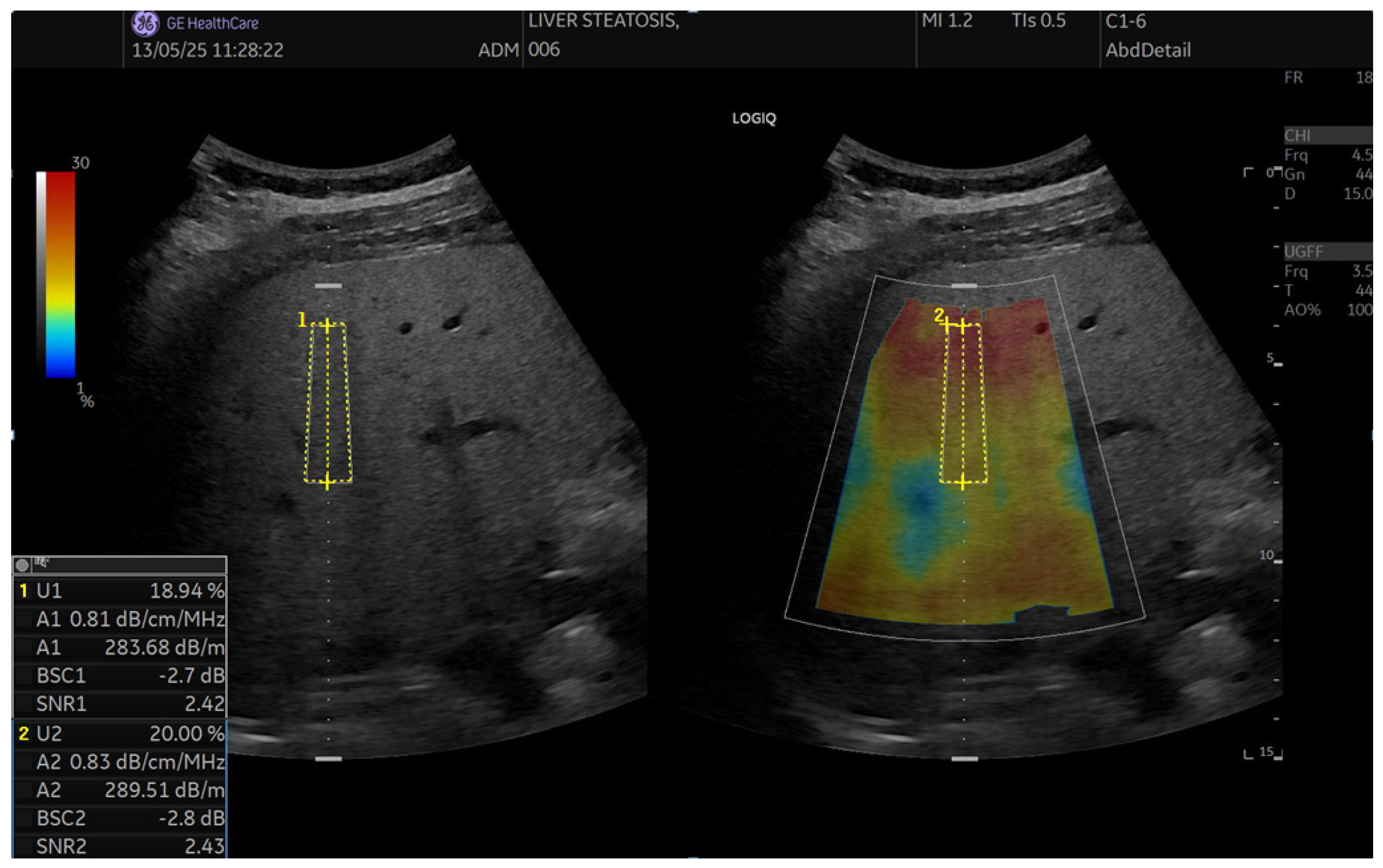

2.5. QUS Protocol (UGFF, AC, BSC, SNR)

2.5.1. Workflow

2.5.2. Ultrasound-Guided Fat Fraction (UGFF)

2.5.3. Attenuation Coefficient (AC, UGAP)

2.5.4. Backscatter Coefficient (BSC)

2.5.5. Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

2.6. CAP Protocol

2.7. Outcomes

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

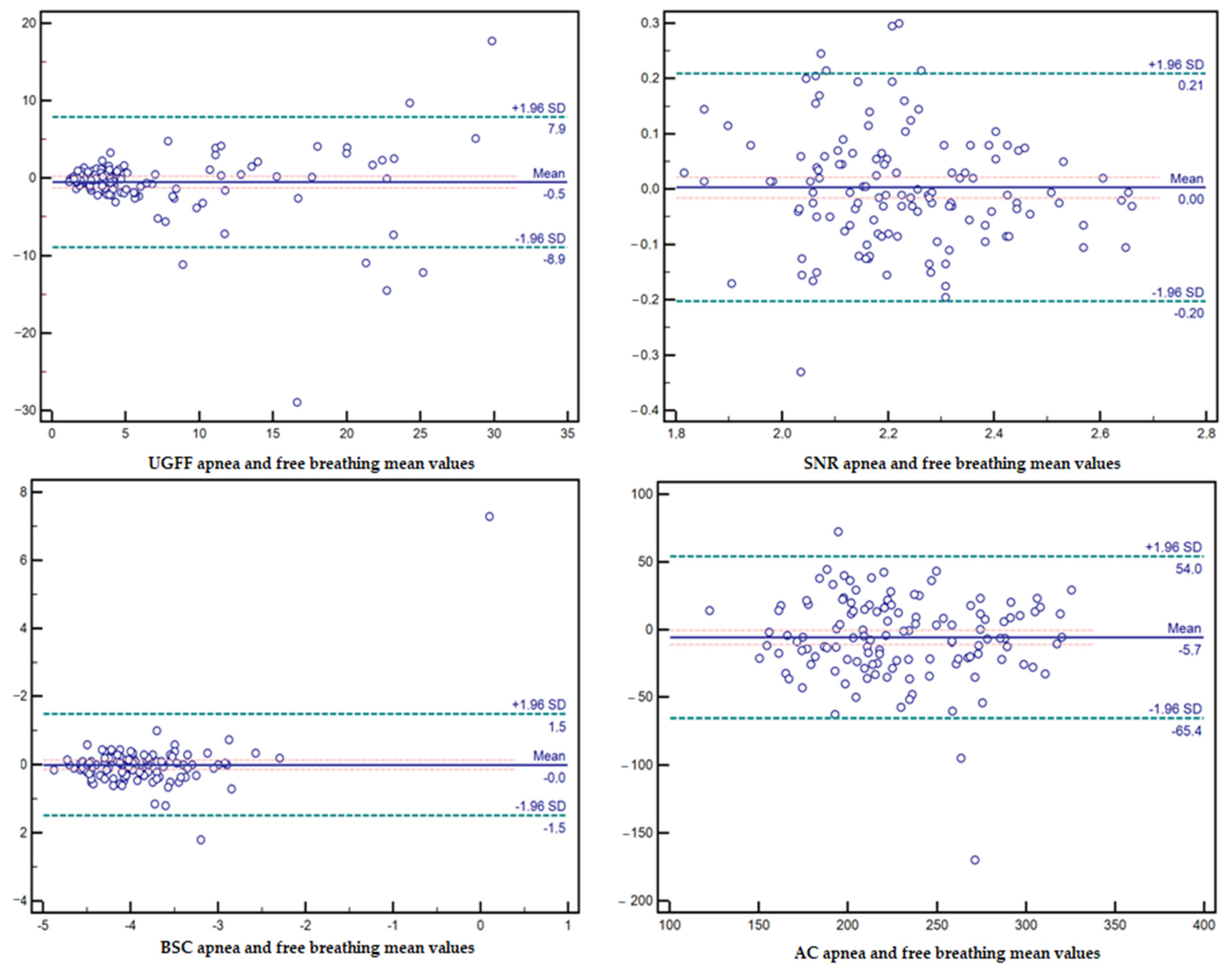

3.2. Effect of Breathing Conditions on the Reliability of Ultrasound Parameters

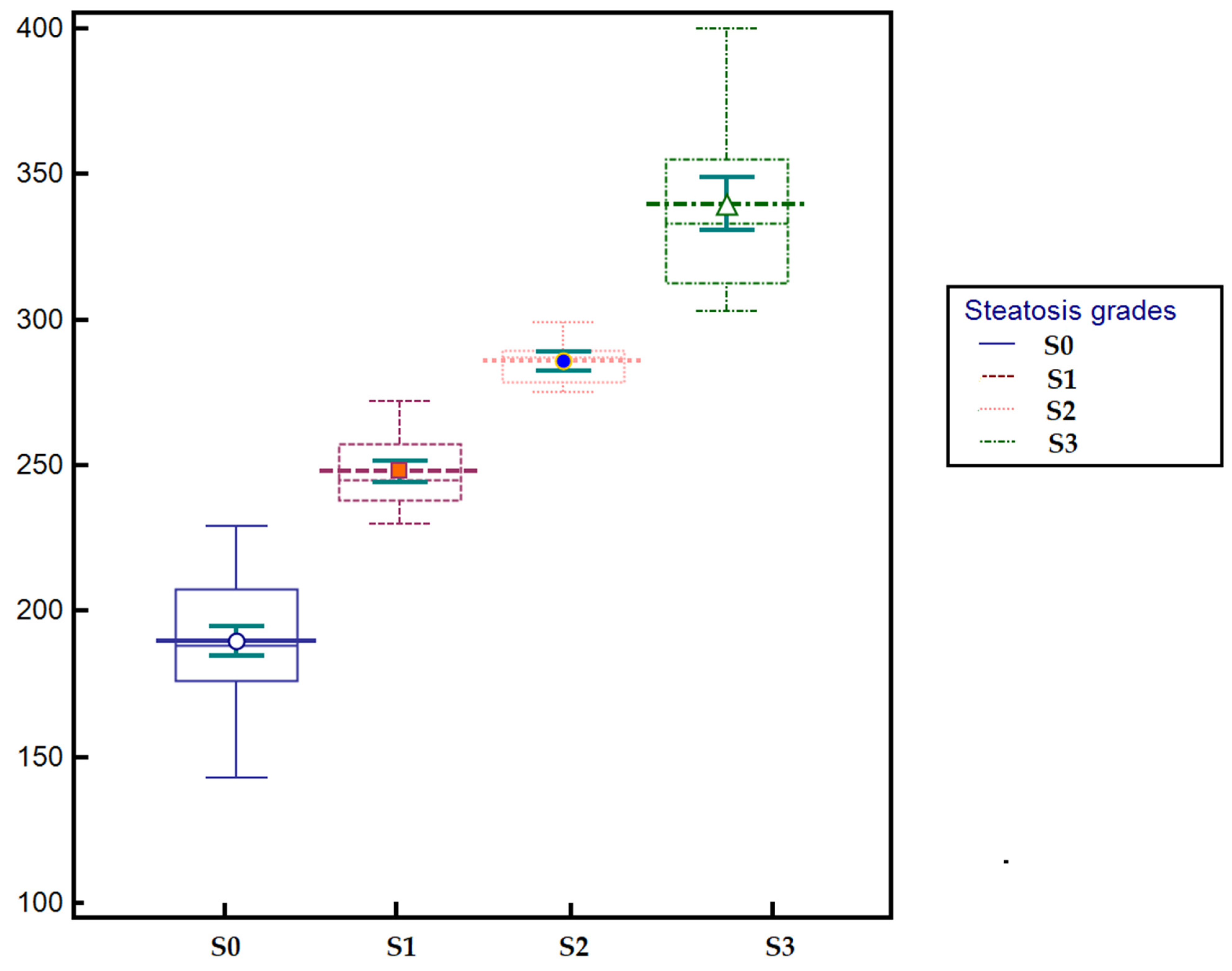

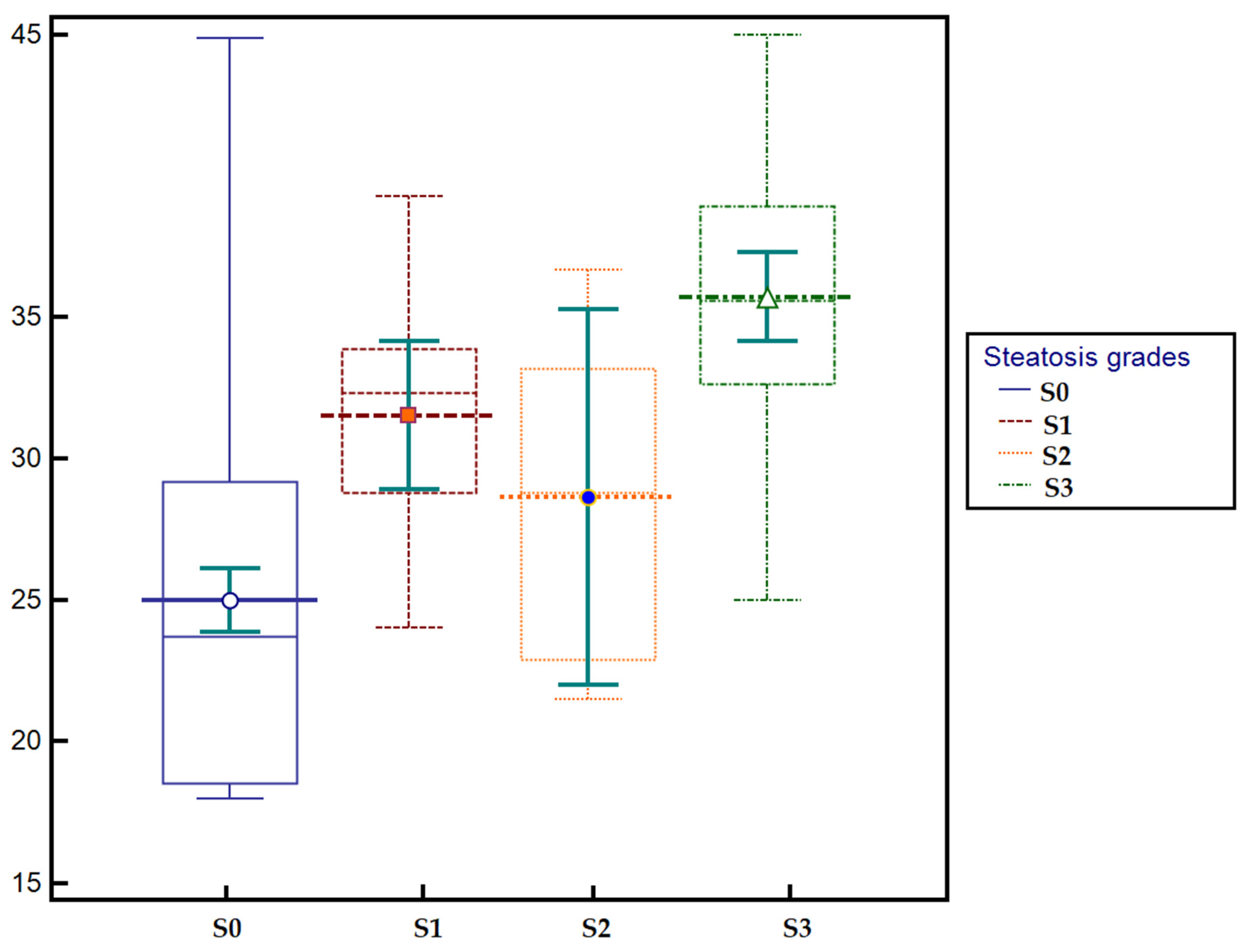

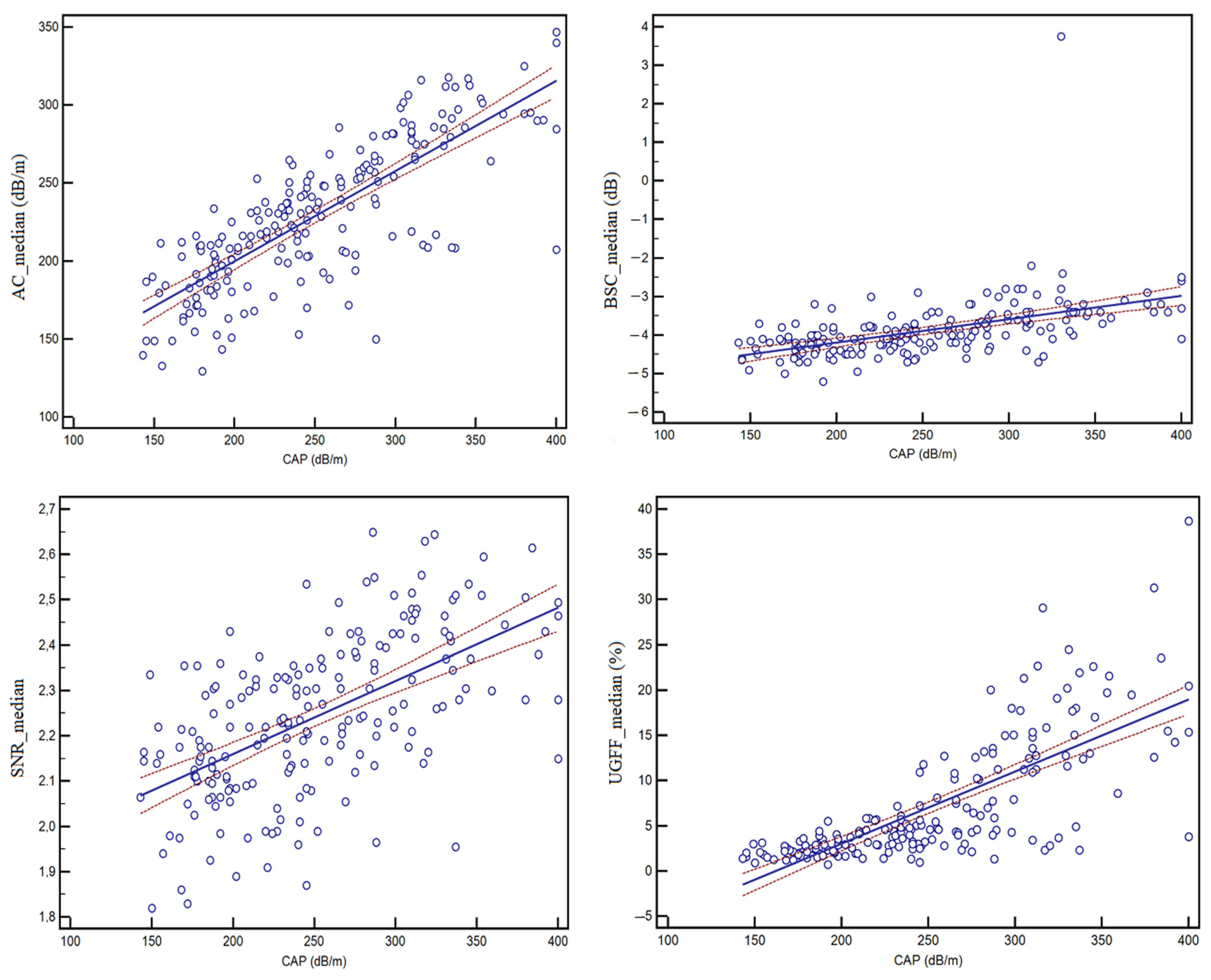

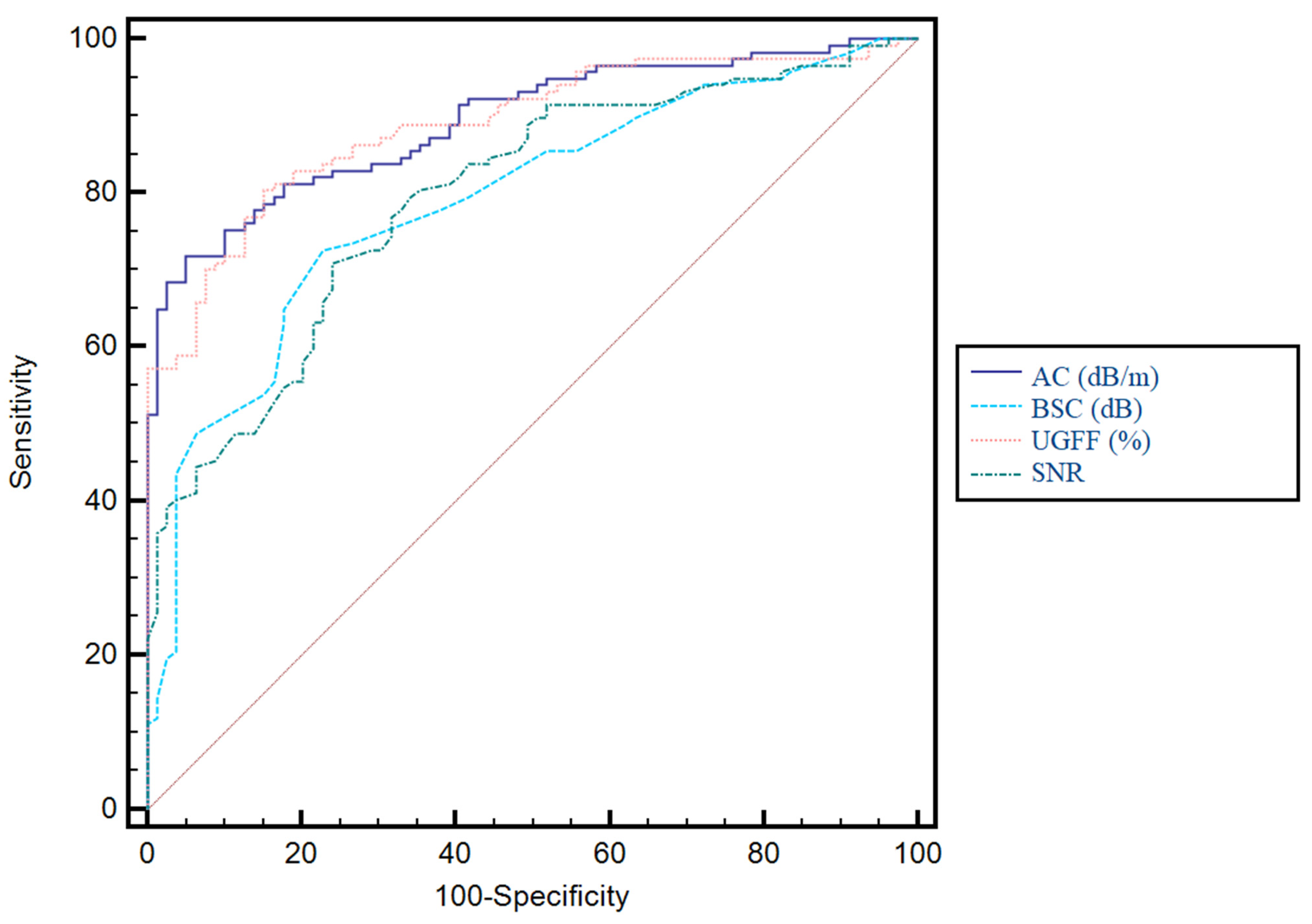

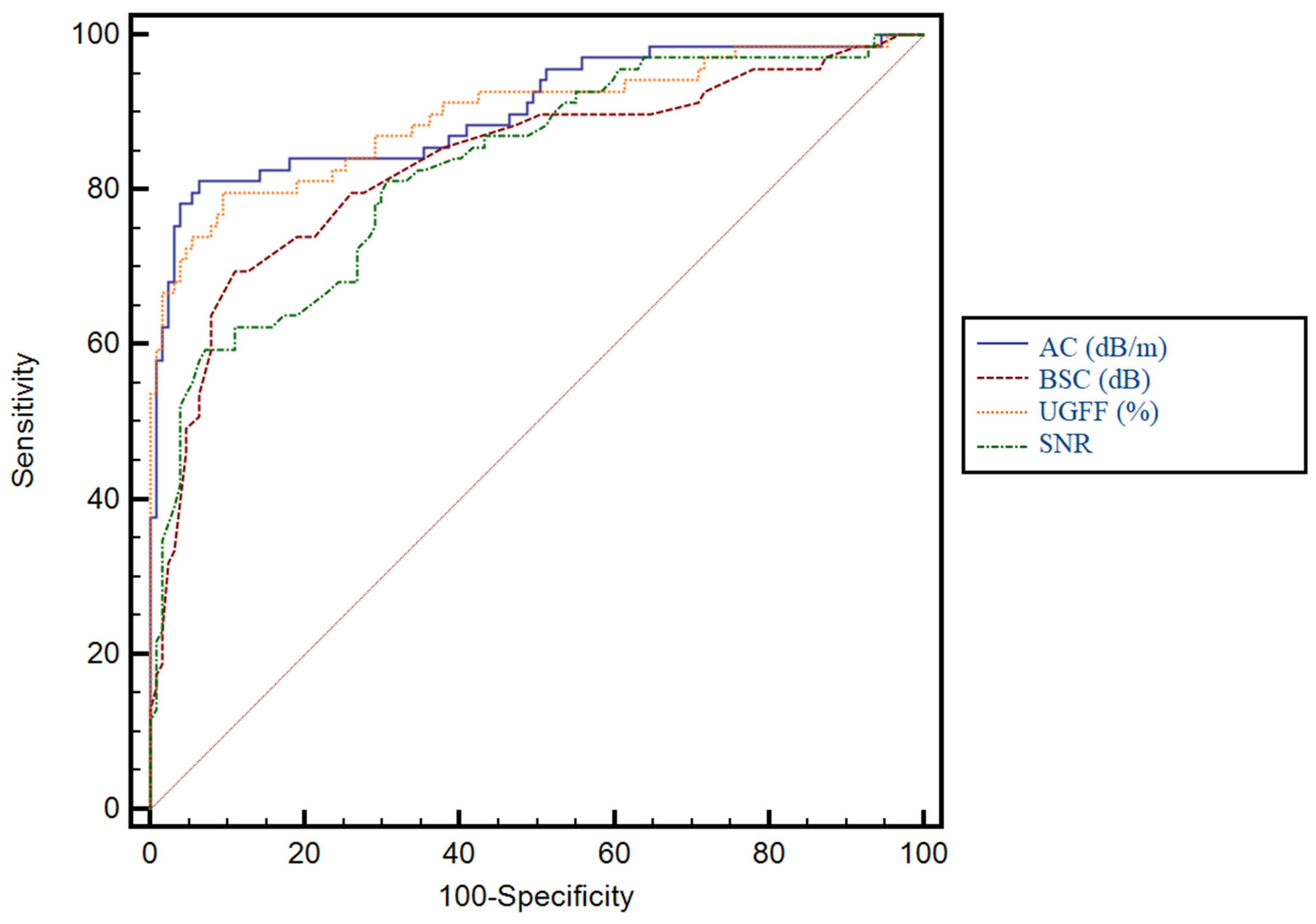

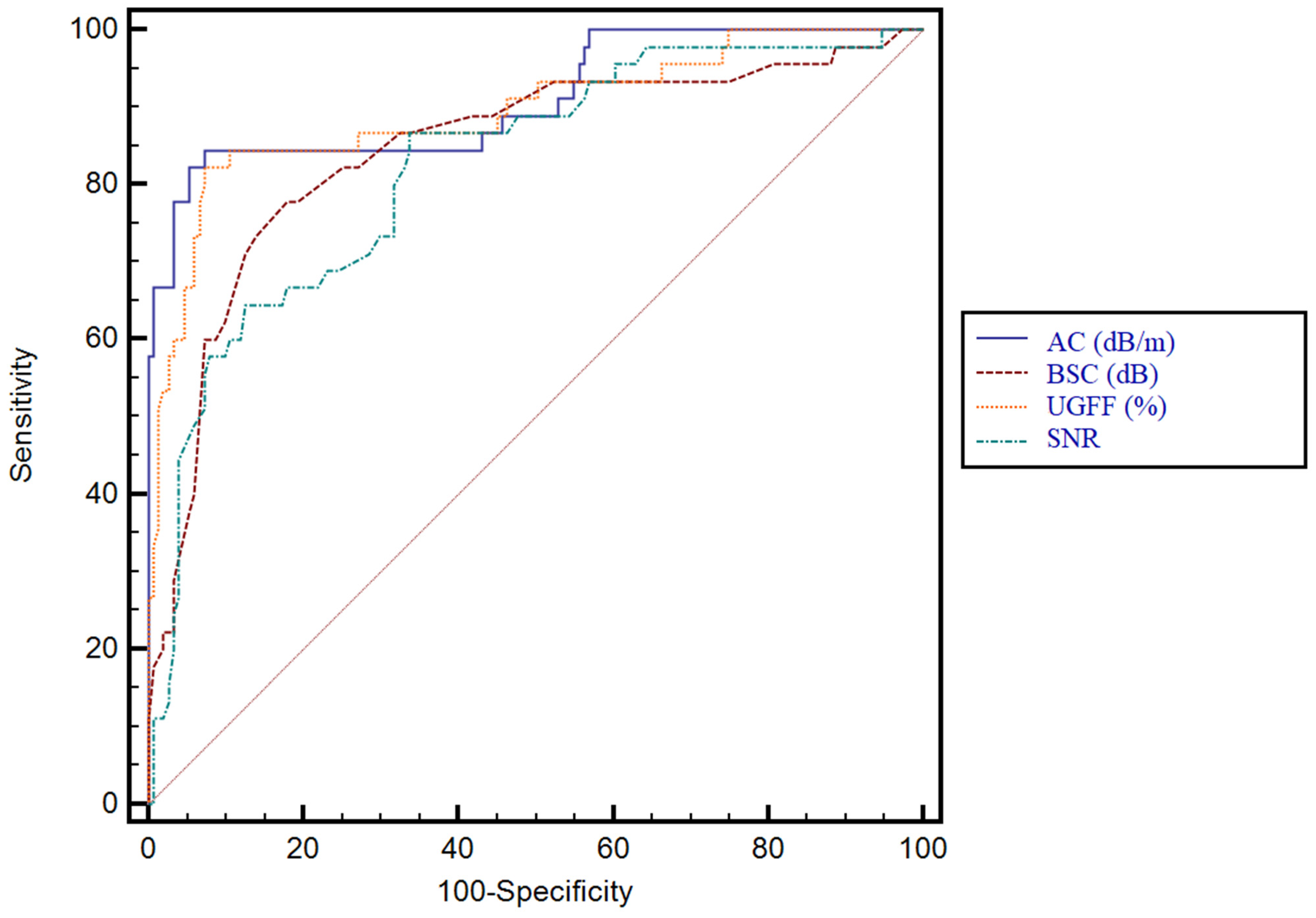

3.3. Predictive Performance of Ultrasound-Derived Parameters for Hepatic Steatosis and Their Correlation with CAP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Attenuation Coefficient |

| ALD | Alcoholic Liver Disease |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area Under the (ROC) Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| B-mode | Brightness-Mode Ultrasound |

| BA | Bland–Altman |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BSC | Backscatter Coefficient |

| CAP | Controlled Attenuation Parameter |

| CAP-IQR | Interquartile Range of CAP measurements |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| dB/m | Decibels per meter |

| EFSUMB | European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HDV | Hepatitis D Virus |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LoA | Limits of Agreement |

| MAFLD | Metabolically Associated Fatty Liver Disease |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MASH | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRI-PDFF | MRI–Proton Density Fat Fraction |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| QIBA | Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance |

| QUS | Quantitative Ultrasound |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| S0–S3 | CAP-Defined Steatosis Grades (none/mild/moderate/severe) |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| TGC | Time-Gain Compensation |

| UGFF | Ultrasound-Guided Fat Fraction (ultrasound fat fraction) |

References

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A Systematic Review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease—Meta-Analytic Assessment of Prevalence, Incidence, and Outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; de Avila, L.; Paik, J.M.; Srishord, M.; Fukui, N.; Qiu, Y.; Burns, L.; Afendy, A.; Nader, F. The Global Epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- En Li Cho, E.; Ang, C.Z.; Quek, J.; Fu, C.E.; Lim, L.K.E.; Heng, Z.E.Q.; Tan, D.J.H.; Lim, W.H.; Yong, J.N.; Zeng, R.; et al. Global Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut 2023, 72, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A Multisociety Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G.; Soares Monteiro, L.B. Ultrasound-Based Techniques for the Diagnosis of Liver Steatosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 6053–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlas, T.; Petroff, D.; Sasso, M.; Fan, J.G.; Mi, Y.Q.; de Lédinghen, V.; Kumar, M.; Lupsor-Platon, M.; Han, K.H.; Cardoso, A.C.; et al. Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) Technology for Assessing Steatosis. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasso, M.; Tengher-Barna, I.; Ziol, M.; Miette, V.; Fournier, C.; Sandrin, L.; Poupon, R.; Cardoso, A.C.; Marcellin, P.; Douvin, C.; et al. Novel Controlled Attenuation Parameter for Noninvasive Assessment of Steatosis Using Fibroscan®: Validation in Chronic Hepatitis C. J. Viral Hepat. 2012, 19, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroff, D.; Blank, V.; Newsome, P.N.; Shalimar; Voican, C.S.; Thiele, M.; de Lédinghen, V.; Baumeler, S.; Chan, W.K.; Perlemuter, G.; et al. Assessment of Hepatic Steatosis by Controlled Attenuation Parameter Using the M and XL Probes: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddowes, P.J.; Sasso, M.; Allison, M.; Tsochatzis, E.; Anstee, Q.M.; Sheridan, D.; Guha, I.N.; Cobbold, J.F.; Deeks, J.J.; Paradis, V.; et al. Accuracy of FibroScan Controlled Attenuation Parameter and Liver Stiffness Measurement in Assessing Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobeika, C.; Ronot, M.; Guiu, B.; Ferraioli, G.; Iijima, H.; Tada, T.; Lee, D.H.; Kuroda, H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, J.M.; et al. Ultrasound-Based Steatosis Grading System Using 2D-Attenuation Imaging: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis with External Validation. Hepatology 2025, 81, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G.; Barr, R.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Sporea, I.; Wong, V.W.; Reiberger, T.; Karlas, T.; Thiele, M.; Cardoso, A.C.; Ayonrinde, O.T.; et al. WFUMB Guidelines/Guidance on Liver Multiparametric Ultrasound. Part 2: Guidance on Liver Fat Quantification. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2024, 50, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, H.; Oguri, T.; Kamiyama, N.; Toyoda, H.; Yasuda, S.; Imajo, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Akita, T.; Tanaka, J.; et al. Multivariable Quantitative US Parameters for Assessing Hepatic Steatosis. Radiology 2023, 309, e230341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaposi, P.N.; Zsombor, Z.; Rónaszéki, A.D.; Budai, B.K.; Csongrády, B.; Stollmayer, R.; Kalina, I.; Győri, G.; Bérczi, V.; Werling, K.; et al. The Calculation and Evaluation of an Ultrasound-Estimated Fat Fraction in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Bamber, J.; Berzigotti, A.; Bota, S.; Cantisani, V.; Castera, L.; Cosgrove, D.; Ferraioli, G.; Friedrich-Rust, M.; Gilja, O.H.; et al. EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Liver Ultrasound Elastography, Update 2017 (Long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2017, 38, e16–e47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bende, F.; Sporea, I.; Sirli, R.; Baldea, V.; Lazar, A.; Lupușoru, R.; Fofiu, R.; Popescu, A. Ultrasound-Guided Attenuation Parameter (UGAP) for the Quantification of Liver Steatosis Using the Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) as the Reference Method. Med. Ultrason. 2021, 23, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.C. No More NAFLD: The Term Is Now MASLD. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 39, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.A.; Bedossa, P.; Guy, C.D.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Loomba, R.; Taub, R.; Labriola, D.; Moussa, S.E.; Neff, G.W.; Rinella, M.E.; et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barb, D.; Kalavalapalli, S.; Godinez Leiva, E.; Bril, F.; Huot-Marchand, P.; Dzen, L.; Rosenberg, J.T.; Junien, J.-L.; Broqua, P.; Rocha, A.O.; et al. Pan-PPAR Agonist Lanifibranor Improves Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis in Patients with T2D and MASLD. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G. CAP for the Detection of Hepatic Steatosis in Clinical Practice. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lédinghen, V.; Vergniol, J.; Capdepont, M.; Chermak, F.; Hiriart, J.B.; Cassinotto, C.; Merrouche, W.; Foucher, J.; Brigitte, L.B. Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) for the Diagnosis of Steatosis: A Prospective Study of 5323 Examinations. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, K.; Wang, Y.; Bai, S.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, J.; Qiao, L. Diagnostic Accuracy of Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) as a Non-Invasive Test for Steatosis in Suspected Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imajo, K.; Toyoda, H.; Yasuda, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Kuroda, H.; Akita, T.; Tanaka, J.; Yasui, Y.; Tamaki, N.; et al. Utility of Ultrasound-Guided Attenuation Parameter for Grading Steatosis with Reference to MRI-PDFF in a Large Cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2533–2541.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rónaszéki, A.D.; Budai, B.K.; Csongrády, B.; Stollmayer, R.; Hagymási, K.; Werling, K.; Fodor, T.; Folhoffer, A.; Kalina, I.; Győri, G.; et al. Tissue Attenuation Imaging and Tissue Scatter Imaging for Quantitative Ultrasound Evaluation of Hepatic Steatosis. Medicine 2022, 101, e29708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G.; Maiocchi, L.; Raciti, M.V.; Tinelli, C.; De Silvestri, A.; Nichetti, M.; De Cata, P.; Rondanelli, M.; Chiovato, L.; Calliada, F.; et al. Detection of Liver Steatosis with a Novel Ultrasound-Based Technique: A Pilot Study Using MRI-Derived Proton Density Fat Fraction as the Gold Standard. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, M.; Ogawa, S.; Koizumi, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Goto, T.; Yasuda, S.; Yamahira, M.; Tamai, T.; Kuromatsu, R.; Matsuzaki, T.; et al. IATT Liver Fat Quantification for Steatosis Grading by Referring to MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction: A Multicenter Study. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 59, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, D.T.; Pierce, T.T.; Robbin, M.L.; Cloutier, G.; Mufti, A.; Hall, T.J.; Chauhan, A.; Kubale, R.; Tang, A. US Quantification of Liver Fat: Past, Present, and Future. RadioGraphics 2023, 43, e220178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labyed, Y.; Milkowski, A. Novel Method for Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction Using an Integrated Phantom. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 2427–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, R.; Spoto, F.; Autelitano, D.; Guagenti, D.; Olivieri, A.; Zanutto, P.; Incarbone, G.; D’Onofrio, M. Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction for Detection of Hepatic Steatosis and Quantification of Liver Fat Content. Radiol. Med. 2023, 128, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Jiao, M.; Yu, C.; Ren, T.; Chen, Q.; Dai, Z.; Xie, E.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y. Discovery of Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction as a Non-Invasive Tool for MASLD Diagnosis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdan, S.; Torri, G.B.; Marcos, V.N.; Moreira, M.H.S.; Defante, M.L.R.; Fagundes, M.d.C.; de Barros, E.M.J.; Dias, A.B.; Shen, L.; Altmayer, S. Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction for Diagnosing Hepatic Steatosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 7421–7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadas, D.; Rafailidis, V.; Liakos, A.; Sinakos, E.; Partovi, S.; Papamitsou, T.; Prassopoulos, P. Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: A Systematic Review Highlighting the Diagnostic Performance of Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Fan, Y.; Yu, J.; Xiong, B.; Zhou, B.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H. Quantitative US Fat Fraction for Noninvasive Assessment of Hepatic Steatosis in Suspected Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, H.; Kakisaka, K.; Kamiyama, N.; Oikawa, T.; Onodera, M.; Sawara, K.; Oikawa, K.; Endo, R.; Takikawa, Y.; Suzuki, K. Non-Invasive Determination of Hepatic Steatosis by Acoustic Structure Quantification from Ultrasound Echo Amplitude. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 3889–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavaglione, F.; Flagiello, V.; Terracciani, F.; Gallo, P.; Capparelli, E.; Spiezia, C.; De Vincentis, A.; Palermo, A.; Scriccia, S.; Galati, G.; et al. Non-Invasive Assessment of Hepatic Steatosis by Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction in Individuals at High-Risk for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Song, K.; Hwang, S.; Han, K.; Ryu, L. Impact of Respiratory Motion on the Quantification of Pediatric Hepatic Steatosis Using Two Different Ultrasonography Machines. Yonsei Med. J. 2024, 65, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, S.; Shen, Z. Consistency and Reliability of Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction in Hepatic Steatosis Assessment: Influence of Posture and Breathing Variations. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G.; Raimondi, A.; De Silvestri, A.; Filice, C.; Barr, R.G. Toward Acquisition Protocol Standardization for Estimating Liver Fat Content Using Ultrasound Attenuation Coefficient Imaging. Ultrasonography 2023, 42, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Son, N.-H.; Chang, D.R.; Chae, H.W.; Shin, H.J. Feasibility of Ultrasound Attenuation Imaging for Assessing Pediatric Hepatic Steatosis. Biology 2022, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Subjects n = 196 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 52.40 ± 13.6 |

| Gender | |

| Males | 116/196 (59.2%) |

| Females | 80/196 (40.8%) |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 27.17 ± 7.52 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 94.60 ± 11.04 |

| AST (U/L) | 49.19 ± 10.80 |

| ALT(U/L) | 38.17 ± 13.60 |

| GGT (U/L) | 93.41 ± 32.57 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 192.11 ± 33.43 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 148.69 ± 34.19 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 242.40 ± 57.32 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.82 ± 0.34 |

| Steatosis distribution | |

| S0 | 79 (40.3%) |

| S1 | 48 (24.5%) |

| S2 | 24 (12.2%) |

| S3 | 45 (23%) |

| Parameter | Apnea Acquisition (Mean ± SD) | Free-Breathing Acquisition (Mean ± SD) | CV Apnea (%) | CV Free Breathing (%) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGFF (%) | 6.71 ± 7.10 | 7.23 ± 7.18 | 105.8 | 99.3 | 0.177 |

| AC (dB/m) | 225.86 ± 45.64 | 231.59 ± 47.60 | 20.2 | 20.6 | 0.036 |

| BSC (dB) | −3.91 ± 0.85 | −3.90 ± 0.52 | 21.9 | 13.2 | 0.953 |

| SNR | 2.23 ± 0.18 | 2.22 ± 0.19 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 0.754 |

| Parameter | AUC | 95% CI | p-Value | Cutoff Value | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGFF (%) | 0.89 | 0.83–0.92 | <0.0001 | 4% | 77% | 84.8% | 88.2% | 71.3% |

| AC (dB/m) | 0.89 | 0.84–0.93 | <0.0001 | 232 | 71.8 | 94.9 | 95.5 | 69.4 |

| BSC (dB) | 0.78 | 0.72–0.84 | <0.0001 | −4 | 72.6 | 77.2 | 82.5 | 65.6 |

| SNR | 0.79 | 0.73–0.84 | <0.0001 | 2.2 | 70.9 | 75.9 | 81.4 | 63.8 |

| Parameter | AUC | 95% CI | p-Value | Cutoff Value | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGFF (%) | 0.89 | 0.84–0.93 | <0.0001 | 6% | 79.7% | 90.5% | 82.1% | 89.1% |

| AC (dB/m) | 0.90 | 0.85–0.94 | <0.0001 | 250 | 81.2 | 93.7 | 87.5 | 90.2 |

| BSC (dB) | 0.83 | 0.77–0.88 | <0.0001 | −3.75 | 69.6 | 89 | 77.4 | 84.3 |

| SNR | 0.82 | 0.76–0.87 | <0.0001 | 2.4 | 59.4 | 92.9 | 82 | 80.8 |

| Parameter | AUC | 95% CI | p-Value | Cutoff Value | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGFF (%) | 0.89 | 0.84–0.93 | <0.0001 | 11% | 80% | 92.7% | 77.6% | 94.1% |

| AC (dB/m) | 0.91 | 0.86–0.94 | <0.0001 | 262 | 84.4 | 92.7 | 77.6 | 95.2 |

| BSC (dB) | 0.84 | 0.78–0.89 | <0.0001 | −3.7 | 77.8 | 82.1 | 56.5 | 92.5 |

| SNR | 0.82 | 0.76–0.87 | <0.0001 | 2.45 | 57.8 | 92 | 68.4 | 88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popa, A.; Sporea, I.; Șirli, R.; Bende, R.; Popescu, A.; Dănilă, M.; Nica, C.; Burciu, C.; Miutescu, B.; Borlea, A.; et al. Multiparametric Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: Comparison with CAP and Robustness Across Breathing States. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243119

Popa A, Sporea I, Șirli R, Bende R, Popescu A, Dănilă M, Nica C, Burciu C, Miutescu B, Borlea A, et al. Multiparametric Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: Comparison with CAP and Robustness Across Breathing States. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243119

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Alexandru, Ioan Sporea, Roxana Șirli, Renata Bende, Alina Popescu, Mirela Dănilă, Camelia Nica, Călin Burciu, Bogdan Miutescu, Andreea Borlea, and et al. 2025. "Multiparametric Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: Comparison with CAP and Robustness Across Breathing States" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243119

APA StylePopa, A., Sporea, I., Șirli, R., Bende, R., Popescu, A., Dănilă, M., Nica, C., Burciu, C., Miutescu, B., Borlea, A., Stoian, D., Maralescu, F., Gadour, E., & Bende, F. (2025). Multiparametric Quantitative Ultrasound for Hepatic Steatosis: Comparison with CAP and Robustness Across Breathing States. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243119