Malignant Transformation of Musculoskeletal Lesions with Imaging–Pathology Correlation—Part 1: Bone Lesions

Abstract

1. Introduction

Methodology

2. Benign Bone Lesions with Malignant Potential: Tumorous Conditions

2.1. Osteochondroma

2.2. Enchondroma

2.3. Giant Cell Tumor of Bone

2.4. Fibrous Dysplasia

2.5. Liposclerosing Myxofibrous Tumor of Bone

3. Benign Bone Lesions with Malignant Potential: Non-Tumorous Conditions

3.1. Chronic Osteomyelitis

3.2. Bone That Underwent Radiation Therapy

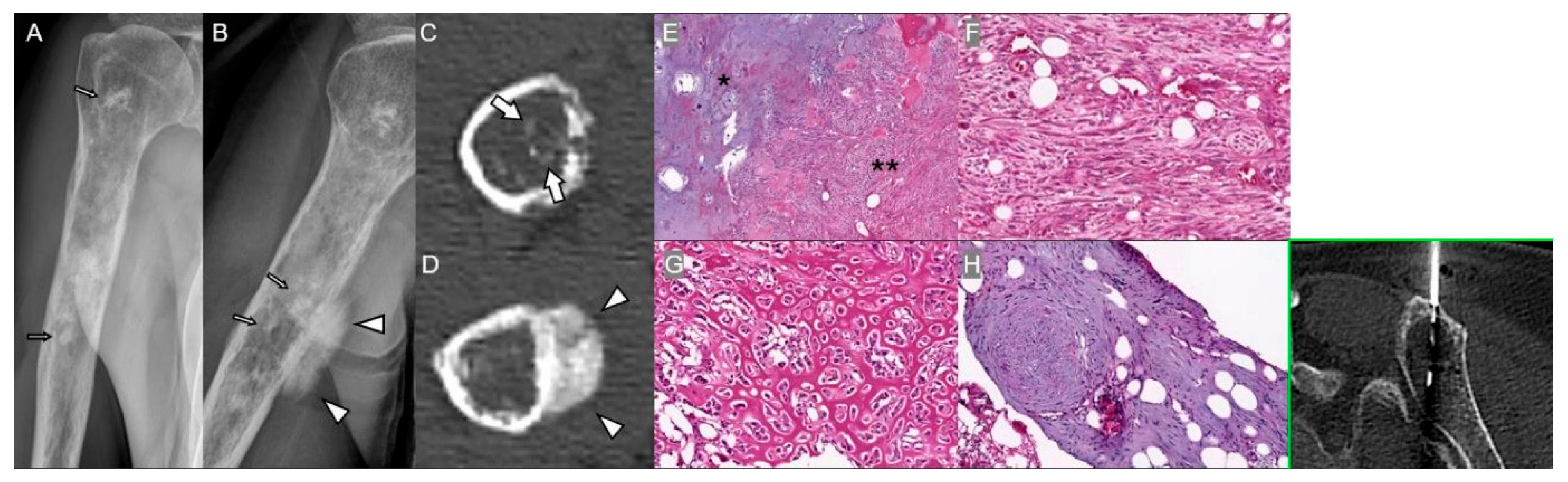

3.3. Bone Infarction

3.4. Paget’s Disease of Bone

4. Low-Grade Malignancies into Higher-Grades

4.1. Low-Grade Central Osteosarcoma

4.2. Conventional Low-Grade Chondrosarcoma

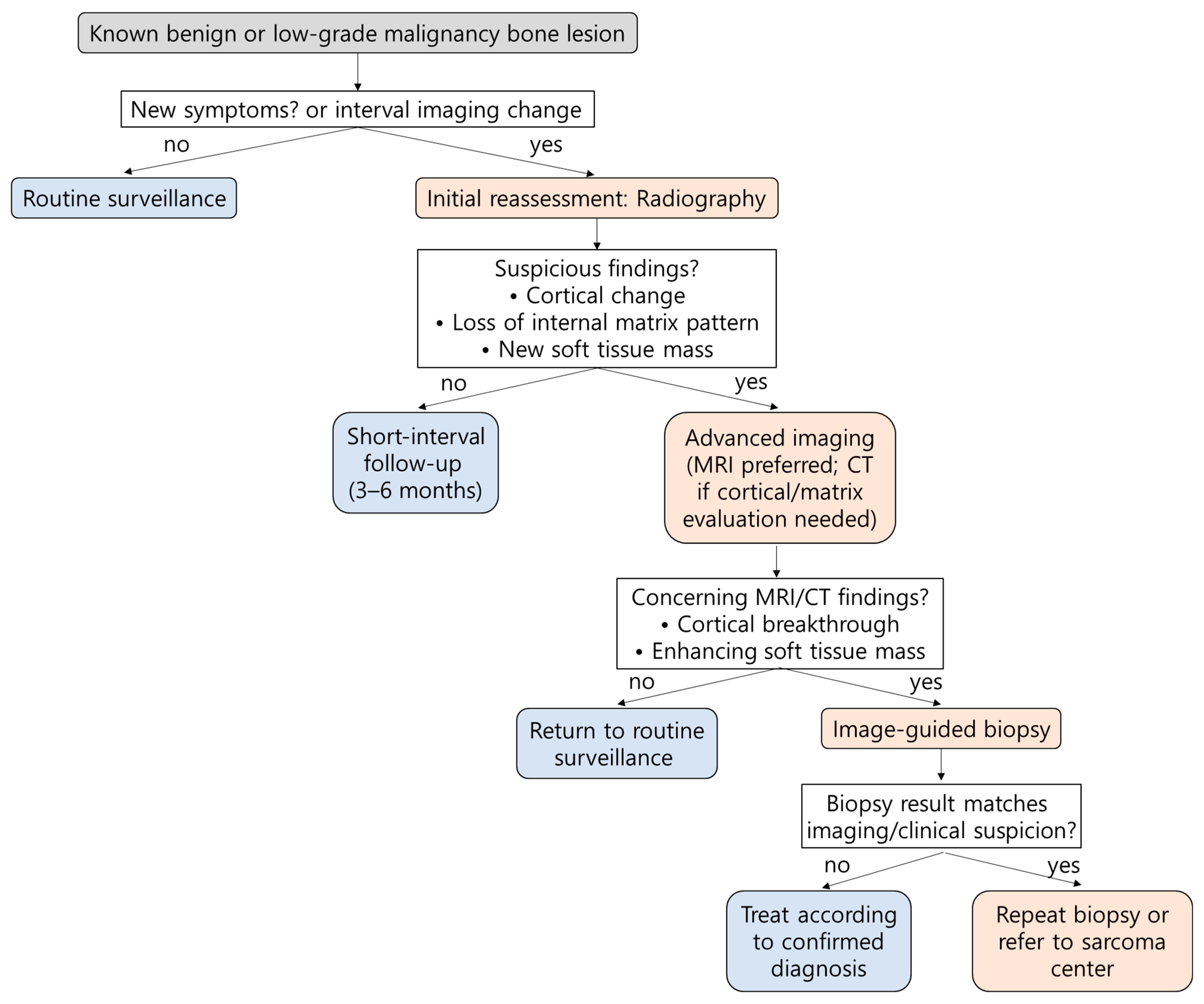

5. Precise Biopsy for Accurate Pathologic Diagnosis

6. Patients at Risk for Malignant Transformation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| GCTB | giant cell tumor of bone |

| LGCOS | low-grade central osteosarcoma |

| LSMFT | liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| RIS | radiation-induced sarcoma |

| SCC | squamous cell carcinoma |

| SI | signal intensity |

| T1WI | T1-weighted image |

| T2WI | T2-weighted image |

| UPS | undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

References

- Garcia, R.A.; Inwards, C.Y.; Unni, K.K. Benign bone tumors—Recent developments. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2011, 28, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepelenis, K.; Papathanakos, G.; Kitsouli, A.; Troupis, T.; Barbouti, A.; Vlachos, K.; Kanavaros, P.; Kitsoulis, P. Osteochondromas: An Updated Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, Radiological Features and Treatment Options. In Vivo 2021, 35, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovée, J.V. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.K. Classification of Chondrosarcoma: From Characteristic to Challenging Imaging Findings. Cancers 2023, 15, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowska-Olech, E.; Trzebiatowska, W.; Czech, W.; Drzymała, O.; Frąk, P.; Klarowski, F.; Kłusek, P.; Szwajkowska, A.; Jamsheer, A. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses-A Review of the Molecular Background, Diagnostics, and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 759129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.R.; Tan, T.S.; Unni, K.K.; Collins, M.S.; Wenger, D.E.; Sim, F.H. Secondary chondrosarcoma in osteochondroma: Report of 107 patients. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 411, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.A.; Murphey, M.D.; Flemming, D.J.; Kransdorf, M.J. Improved differentiation of benign osteochondromas from secondary chondrosarcomas with standardized measurement of cartilage cap at CT and MR imaging. Radiology 2010, 255, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, K.J.; Ayala, A.G.; Ro, J.Y. Chondrosarcoma: With updates on molecular genetics. Sarcoma. 2011, 2011, 405437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Joo, M.W. Quantitative Bone SPECT/CT of Central Cartilaginous Bone Tumors: Relationship between SUVmax and Radiodensity in Hounsfield Unit. Cancers 2024, 16, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venneker, S.; Kruisselbrink, A.B.; Baranski, Z.; Palubeckaite, I.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.H.; Oosting, J.; French, P.J.; Danen, E.H.; Bovée, J.V. Beyond the Influence of IDH Mutations: Exploring Epigenetic Vulnerabilities in Chondrosarcoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, E.W.; Mirra, J.M.; Kerr, R. Benign and malignant cartilage tumors of bone and joint: Their anatomic and theoretical basis with an emphasis on radiology, pathology and clinical biology. I. The intramedullary cartilage tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 1997, 26, 325–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarun, C.J.; Forrester, D.M.; Gottsegen, C.J.; Patel, D.B.; White, E.A.; Matcuk, G.R., Jr. Giant cell tumor of bone: Review, mimics, and new developments in treatment. Radiographics 2013, 33, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; Andrei, V.; Pollock, R.; Saifuddin, A. Malignant giant cell tumour of bone: A review of clinical, pathological and imaging features. Skeletal Radiol. 2022, 51, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwasaki, T.; Toda, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Yoshimoto, M.; Ito, Y.; Susuki, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kinoshita, I.; et al. Histological and immunohistochemical features and genetic alterations in the malignant progression of giant cell tumor of bone: A possible association with TP53 mutation and loss of H3K27 trimethylation. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanacci, M.; Baldini, N.; Boriani, S.; Sudanese, A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1987, 69, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chan, C.M.; Gong, L.; Bui, M.M.; Han, G.; Letson, G.D.; Yang, Y.; Niu, X. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone in the extremities. J. Bone Oncol. 2021, 26, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kransdorf, M.J.; Moser, R.P.; Jr Gilkey, F.W. Fibrous dysplasia. Radiographics 1990, 10, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Smoker, W.R.; Frable, W.J. Malignant transformation of fibrous dysplasia into chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2002, 31, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Ma, M.; Feng, Y.; Li, T. Clinicopathological and genetic study of a rare occurrence: Malignant transformation of fibrous dysplasia of the jaws. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2022, 10, e1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.L.; Ke, M.; Yuan, X.Y.; Zhang, J.S. Multimodal imaging diagnosis for bone fibrous dysplasia malignant transformation: A case report. Biomed. Rep. 2023, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kransdorf, M.J.; Murphey, M.D.; Sweet, D.E. Liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor: A radiologic-pathologic-distinct fibro-osseous lesion of bone with a marked predilection for the intertrochanteric region of the femur. Radiology 1999, 212, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, M.D.; Carroll, J.F.; Flemming, D.J.; Pope, T.L.; Gannon, F.H.; Kransdorf, M.J. From the archives of the AFIP: Benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics 2004, 24, 1433–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Wodajo, F. Case report: Two-step malignant transformation of a liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor of bone. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 2873–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkey, F.W. Liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor of bone. Hum. Pathol. 1993, 24, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Burgos, E.M.; Serra del Carpio, G.; Tapia-Viñe, M.; Suárez-González, J.; Buño, I.; Ortiz-Cruz, E.; Pozo-Kreilinger, J.J. Liposclerosing Myxofibrous Tumor: A Separated Clinical Entity? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regado, E.R.; Garcia, P.B.L.; Caruso, A.C.; de Almeida, A.L.B.; Aymoré, I.L.; Meohas, W.; Aguiar, D.P. Liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor: A series of 9 cases and review of the literature. J. Orthop. 2016, 13, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Sadigh, S.; Mankad, K.; Kapse, N.; Rajeswaran, G. The imaging of osteomyelitis. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2016, 6, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardon, M.; Alaia, E.F. Approach to imaging modalities in the setting of suspected infection. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekarek, B.; Buck, S.; Osher, L.A. Comprehensive Review on Marjolin’s Ulcers: Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Col. Certif. Wound Spec. 2011, 3, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, R.A.; Barlow, G.; Hartley, C.; McNally, M. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating chronic osteomyelitis: A systematic review and case series. Surgeon 2022, 20, e322–e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lee, J.; Cho, W.H.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, M.J.; Bae, K.E. MR Findings of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising from Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Tibia: A Case Report. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 2016, 74, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: Signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Tu, Y.; Long, Z.; Liu, J.; Kong, D.; Peng, J.; Wu, H.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Bridge the Gap between Chronic Inflammation and Tumor Development. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2606928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Mello, L.F.B.; Nogueira Neto, N.C.; Meohas, W.; Pinto, L.W.; Campos, V.A.; Barcellos, M.G.; Fiod, N.J.; Rezende, J.F.N.; Cabral, C.E.L. Malignancy in chronic ulcers and scars of the leg (Marjolin’s ulcer): A study of 21 patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2001, 30, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Logan, P.M. Radiation-induced changes in bone. Radiographics 1998, 18, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurino, S.; Omer, L.C.; Albano, F.; Marino, G.; Bianculli, A.; Solazzo, A.P.; Sgambato, A.; Falco, G.; Russi, S.; Bochicchio, A.M. Radiation-induced sarcomas: A single referral cancer center experience and literature review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 986123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, W.G.; Woodard, H.Q.; Higinbotham, N.L.; Stewart, F.W.; Coley, B.L. Sarcoma arising in irradiated bone: Report of eleven cases. 1948. Cancer 1998, 82, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorigan, J.G.; Libshitz, H.I.; Peuchot, M. Radiation-induced sarcoma of bone: CT findings in 19 cases. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1989, 153, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.C.; Yang, J.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.T.; Shen, L.J.; Xu, B.S.; Que, Y.; Xia, X.; Zhang, X. Genomic Profiling of Radiation-Induced Sarcomas Reveals the Immunologic Characteristics and Its Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2869–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonin-Laurent, N.; Hadj-Hamou, N.S.; Vogt, N.; Houdayer, C.; Gauthiers-Villars, M.; Dehainault, C.; Sastre-Garau, X.; Chevillard, S.; Malfoy, B. RB1 and TP53 pathways in radiation-induced sarcomas. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6106–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesluyes, T.; Baud, J.; Pérot, G.; Charon-Barra, C.; You, A.; Valo, I.; Bazille, C.; Mishellany, F.; Leroux, A.; Renard-Oldrini, S.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic comparison of post-radiation versus sporadic sarcomas. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 1786–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O′Regan, K.; Hall, M.; Jagannathan, J.; Giardino, A.; Kelly, P.J.; Butrynski, J.; Ramaiya, N. Imaging of radiation-associated sarcoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, W30–W36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghami, E.G.; St-John, M.; Bhuta, S.; Abemayor, E. Postirradiation sarcoma: A case report and current review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2005, 26, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, M.D.; Foreman, K.L.; Klassen-Fischer, M.K.; Fox, M.G.; Chung, E.M.; Kransdorf, M.J. From the radiologic pathology archives imaging of osteonecrosis: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2014, 34, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, G.S.; Lo, R.; Montag, A. Infarct-Associated Bone Sarcomas: Multimodality Imaging Findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 205, W432–W441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, M.; Park, H.K.; Yu, D.B.; Jung, K.; Song, K.; Choi, Y.L. Co-expression of MDM2 and CDK4 in transformed human mesenchymal stem cells causes high-grade sarcoma with a dedifferentiated liposarcoma-like morphology. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, M.D.; Sadigh, S.; Weber, K.L.; Sebro, R. A Rare Case of an Osteolytic Bone-infarct-associated Osteosarcoma: Case Report with Radiographic and Histopathologic Correlation, and Literature Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konarski, W.; Poboży, T.; Hordowicz, M.; Śliwczyński, A.; Kotela, I.; Krakowiak, J.; Kotela, A. Bone Infarcts and Tumorigenesis-Is There a Connection? A Mini-Mapping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.X.; Kyriakos, M. Bone infarct-associated osteosarcoma. Cancer 1992, 70, 2418–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, I.F.; Klein, M.J.; Hermann, G.; Springfield, D. Angiosarcomas associated with bone infarcts. Skeletal Radiol. 1998, 27, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spazzoli, B.; Danna, G.; Laranga, R.; Gambarotti, M.; Donati, D. Secondary osteosarcoma arising on one of multiple areas of avascular bone necrosis caused by corticosteroid therapy: Case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Images Surg. 2021, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortis, K.; Micallef, K.; Mizzi, A. Imaging Paget’s disease of bone—From head to toe. Clin. Radiol. 2011, 66, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.F.; Aihara, A.Y.; Fernandes, A.; Cardoso, F.N. Imaging of Paget’s Disease of Bone. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 60, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirra, J.M.; Brien, E.W.; Tehranzadeh, J. Paget’s disease of bone: Review with emphasis on radiologic features, Part, I. Skelet. Radiol. 1995, 24, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Mirra, J.M.; Brien, E.W.; Tehranzadeh, J. Paget’s disease of bone: Review with emphasis on radiologic features, Part II. Skelet. Radiol. 1995, 24, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, H.; Mehdi, S.A.; MacDuff, E.; Reece, A.T.; Jane, M.J.; Reid, R. Paget sarcoma of the spine: Scottish Bone Tumor Registry experience. Spine 2006, 31, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendina, D.; De Filippo, G.; Ralston, S.H.; Merlotti, D.; Gianfrancesco, F.; Esposito, T.; Muscariello, R.; Nuti, R.; Strazzullo, P.; Gennari, L. Clinical characteristics and evolution of giant cell tumor occurring in Paget’s disease of bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, T.P.; Long, J.; Layfield, R.; Searle, M.S. Impact of p62/SQSTM1 UBA Domain Mutations Linked to Paget’s Disease of Bone on Ubiquitin Recognition. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 4665–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, N.; Brown, J.P.; Morissette, J.; Raymond, V. Recurrent Mutation of the Gene Encoding sequestosome 1 (<em>SQSTM1/p62</em>) in Paget Disease of Bone. Am. J. Hum. Human. Genet. 2002, 70, 1582–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Caravita, T.; Siniscalchi, A.; Montinaro, E.; Bove, R.; Zaccagnini, M.; De Pascalis, D.; Morocutti, A.; Brusa, L.; Arciprete, F.; Cupini, M.L.; et al. Multiple myeloma and paget disease with abnormal skull lesions and intracranial hypertension. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 4, e2012068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Puri, A.; Shah, S.; Rekhi, B.; Gulia, A. Giant Cell Tumor Developing in Paget’s Disease of Bone: A Case Report with Review of Literature. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2016, 6, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston, S.H.; Corral-Gudino, L.; Cooper, C.; Francis, R.M.; Fraser, W.D.; Gennari, L.; Guanabens, N.; Javaid, M.K.; Layfield, R.; O′Neill, T.W.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Paget’s Disease of Bone in Adults: A Clinical Guideline. J. Bone Min. Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, K.J.; Sundaram, M.; Unni, K.K.; Sim, F.H. Imaging features of low-grade central osteosarcoma of the long bones and pelvis. Skelet. Radiol. 2004, 33, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhas, A.M.; Sumathi, V.P.; James, S.L.; Menna, C.; Carter, S.R.; Tillman, R.M.; Jeys, L.; Grimer, R.J. Low-grade central osteosarcoma: A difficult condition to diagnose. Sarcoma 2012, 2012, 764796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Tewari, S.; Singh, A.; Misra, V. Low grade central osteosarcoma transforming to high grade sarcoma—Clinical implications and brief review of literature ! Indian J. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 7, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujardin, F.; Binh, M.B.N.; Bouvier, C.; Gomez-Brouchet, A.; Larousserie, F.; De Muret, A.; Louis-Brennetot, C.; Aurias, A.; Coindre, J.M.; Guillou, L.; et al. MDM2 and CDK4 immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of low-grade osteosarcomas and other primary fibro-osseous lesions of the bone. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Ushiku, T.; Motoi, T.; Shibata, T.; Beppu, Y.; Fukayama, M.; Tsuda, H. Immunohistochemical analysis of MDM2 and CDK4 distinguishes low-grade osteosarcoma from benign mimics. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.C.; Beird, H.C.; Andrew Livingston, J.; Advani, S.; Mitra, A.; Cao, S.; Reuben, A.; Ingram, D.; Wang, W.L.; Ju, Z.; et al. Immuno-genomic landscape of osteosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunder, J.S.; Gokgoz, N.; Parkes, R.; Bull, S.B.; Eskandarian, S.; Davis, A.M.; Beauchamp, C.P.; Conrad, E.U.; Grimer, R.J.; Healey, J.H.; et al. TP53 Mutations and Outcome in Osteosarcoma: A Prospective, Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Ushiku, T.; Motoi, T.; Beppu, Y.; Fukayama, M.; Tsuda, H.; Shibata, T. MDM2 and CDK4 immunohistochemical coexpression in high-grade osteosarcoma: Correlation with a dedifferentiated subtype. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvidou, O.; Papakonstantinou, O.; Lakiotaki, E.; Zafeiris, I.; Melissaridou, D. Surface bone sarcomas: An update on current clinicopathological diagnosis and treatment. EFORT Open Rev. 2021, 6, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphey, M.D.; Walker, E.A.; Wilson, A.J.; Kransdorf, M.J.; Temple, H.T.; Gannon, F.H. From the archives of the AFIP: Imaging of primary chondrosarcoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2003, 23, 1245–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusho, C.A.; Lee, L.; Zavras, A.; Seikel, Z.; Miller, I.; Colman, M.W.; Gitelis, S.; Blank, A.T. Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Orthop. Rev. 2022, 14, 35448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xi, Y.; Li, M.; Jiao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Yao, W. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma: Radiological features, prognostic factors and survival statistics in 23 patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, R.; Ayadi, M.; Gomez-Brouchet, A.; Armenoult, L.; Banneau, G.; Elarouci, N.; Tallegas, M.; Decouvelaere, A.V.; Aubert, S.; Rédini, F.; et al. Integrated molecular characterization of chondrosarcoma reveals critical determinants of disease progression. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, R.A.; Yang, R.K.; Lazar, A.J.; Patel, S.S.; Lewis, V.O.; Roszik, J.; Livingston, J.A.; Wang, W.L.; Shaw, K.R.; Ratan, R.; et al. Clinico-Genomic Profiling of Conventional and Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcomas Reveals TP53 Mutation to Be Associated with Worse Outcomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 4844–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Lyskjær, I.; Lesluyes, T.; Hargreaves, S.; Strobl, A.C.; Davies, C.; Waise, S.; Hames-Fathi, S.; Oukrif, D.; Ye, H.; et al. A genetic model for central chondrosarcoma evolution correlates with patient outcome. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Hornicek, F.J.; Duan, Z. Advances in the Molecular Biology of Chondrosarcoma for Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine. Cancers 2025, 17, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, W.; Dróżdż, J.; Kisielewska, W.; Karwowska, W.; Dudzisz-Śledź, M.; Zając, A.E.; Borkowska, A.; Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A.; Szostakowski, B.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma from Molecular Pathology to Current Treatment and Clinical Trials. Cancers 2023, 15, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Jee, W.H.; Jung, C.K.; Chung, Y.G. Multiparametric quantitative analysis of tumor perfusion and diffusion with 3T MRI: Differentiation between benign and malignant soft tissue tumors. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20191035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.T.; Valadez, S.D.; Chivers, F.S.; Roberts, C.C.; Beauchamp, C.P. Anatomically based guidelines for core needle biopsy of bone tumors: Implications for limb-sparing surgery. Radiographics 2007, 27, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Langevelde, K.; Cleven, A.H.G.; Navas Cañete, A.; van der Heijden, L.; van de Sande, M.A.J.; Gelderblom, H.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. Malignant Transformation of Giant Cell Tumor of Bone and the Association with Denosumab Treatment: A Radiology and Pathology Perspective. Sarcoma 2022, 2022, 3425221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righi, A.; Paioli, A.; Dei Tos, A.P.; Gambarotti, M.; Palmerini, E.; Cesari, M.; Marchesi, E.; Donati, D.M.; Picci, P.; Ferrari, S. High-grade focal areas in low-grade central osteosarcoma: High-grade or still low-grade osteosarcoma? Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2015, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, H.; Takatsu, T.; Imai, R. Radiation-induced osteosarcoma in the pubic bone after proton radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A case report. J. Rural. Med. 2022, 17, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D′Arienzo, A.; Andreani, L.; Sacchetti, F.; Colangeli, S.; Capanna, R. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: Current Insights. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Griffin, A.M.; Ferguson, P.C.; Wunder, J.S. Developing an Evidence-based Followup Schedule for Bone Sarcomas Based on Local Recurrence and Metastatic Progression. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, iii113–iii123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lesion | Key Clinical Indicators | Imaging Red Flags | Pathologic Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteochondroma | New or progressive pain, growth after skeletal maturity; usually long-standing lesion (>10 yr) | Cartilage cap > 2 cm (adult), irregular or lobulated contour, soft-tissue mass | Increased cellularity, binucleated chondrocytes, cortical invasion |

| Enchondroma | Persistent pain, enlargement, fracture; risk ↑ in Ollier’s (10–20%) and Maffucci (up to 100%) | Endosteal scalloping > 2/3 cortex, cortical thickening or destruction, irregular calcifications | Trabecular permeation increased atypia, marrow fat replacement |

| Giant Cell Tumor of Bone | May occur primarily or 10 yr post-surgery/radiation; Recurrence, rapid symptoms post-treatment | Cortical destruction, new soft-tissue extension, aggressive periosteal reaction | Sarcomatous spindle transformation, high mitotic activity |

| Fibrous Dysplasia | Rapid swelling, new pain, post-radiation change | Loss of ground-glass pattern, mixed sclerotic/lytic change, cortical breach | High-grade atypia, malignant osteoid/chondroid matrix |

| Liposclerosing Myxofibrous Tumor | Transformation latency 5–15 yr; new pain or recurrence after curettage | Rapid lesion growth, soft-tissue extension, heterogeneous enhancement | Osteoid formation or UPS features |

| Chronic Osteomyelitis | Long latency (20–30 yr), foul odor, long-standing sinus tract | Irregular osteolysis, mixed lytic–sclerotic changes, enhancing mass at sinus tract | Squamous cell carcinoma from sinus epithelium |

| Post-Radiation Bone | Appears 5–20 yr post-radiation (>3000 cGy); new mass | New lytic lesion in irradiated field, cortical destruction, soft-tissue extension | High-grade sarcoma (OS/UPS) with radiation-related atypia |

| Bone Infarction | Long latency (10–20 yr), new or disproportionate pain | Loss of sclerotic rim, focal lysis, cortical destruction | Atypical spindle cells, osteoid/fibrous matrix |

| Paget’s Disease | New focal pain or mass in long-standing disease | Aggressive lytic lesion, cortical destruction, soft-tissue mass | Malignant osteoid → Secondary osteosarcoma; may also develop Paget-related GCT or hematologic malignancy |

| Low-Grade Central Osteosarcoma | Recurrence after incomplete resection/curettage within 3–5 yr | Mixed sclerotic–lytic intramedullary lesion → later permeative destruction and soft-tissue extension | Bland spindle cells with woven osteoid → dedifferentiation to high-grade OS (loss of MDM2/CDK4) |

| Low-Grade Conventional Chondrosarcoma | Dedifferentiation after long latency (>5 yr); sudden pain, or pathologic fracture | Lobulated lesion with ring-and-arc calcification → loss of matrix, cortical breakthrough, solid enhancement | Biphasic lesion: low-grade cartilage adjacent to high-grade UPS/OS component |

| Category | Key Examples | Mechanism/Risk Basis | Recommended Surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic syndromes | Multiple hereditary exostoses, Ollier disease, Maffucci syndrome | EXT or IDH mutations → abnormal cartilage growth with increased risk of secondary chondrosarcoma | Annual imaging (MRI or radiograph) and lifelong follow-up |

| Medication-related | Denosumab-treated GCTB | RANKL inhibition may induce aberrant osteoblastic proliferation and sarcomatous transformation (OS or UPS) | MRI every 6–12 months after cessation |

| Surgery-related | Marginal or intralesional excision of low-grade osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma | Residual tumor cells may dedifferentiate into high-grade sarcoma | Long-term surveillance; recurrence within 3–5 years |

| Radiation-related | Bone within prior irradiation field (>3000 cGy) | Radiation-induced DNA damage and osteonecrosis | Begin MRI/CT at 5 years post-radiation; continue ≥ 20 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, H.S.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, J.-Y.; Yoo, C.; Joo, M.W. Malignant Transformation of Musculoskeletal Lesions with Imaging–Pathology Correlation—Part 1: Bone Lesions. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243120

Jeong HS, Lee SK, Kim J-Y, Yoo C, Joo MW. Malignant Transformation of Musculoskeletal Lesions with Imaging–Pathology Correlation—Part 1: Bone Lesions. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243120

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Hyang Sook, Seul Ki Lee, Jee-Young Kim, Changyoung Yoo, and Min Wook Joo. 2025. "Malignant Transformation of Musculoskeletal Lesions with Imaging–Pathology Correlation—Part 1: Bone Lesions" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243120

APA StyleJeong, H. S., Lee, S. K., Kim, J.-Y., Yoo, C., & Joo, M. W. (2025). Malignant Transformation of Musculoskeletal Lesions with Imaging–Pathology Correlation—Part 1: Bone Lesions. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243120