Depth-Resolved OCT of Root Canal Walls After Diode-Laser Irradiation: A Descriptive Ex Vivo Study Following a Stereomicroscopy Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Teeth, Eligibility Criteria, and Sample Preparation

2.3. Chemo-Mechanical Preparation

2.4. Study Groups and Laser Irradiation Protocols

- Group A (Conventional protocol): 15 teeth; diode-laser irradiation performed as per recommended clinical settings.

- Group B (Higher-power protocol): 10 teeth; diode-laser irradiation performed at increased power and without pauses between cycles.

- Group C (Control): 10 teeth; no diode-laser irradiation applied.

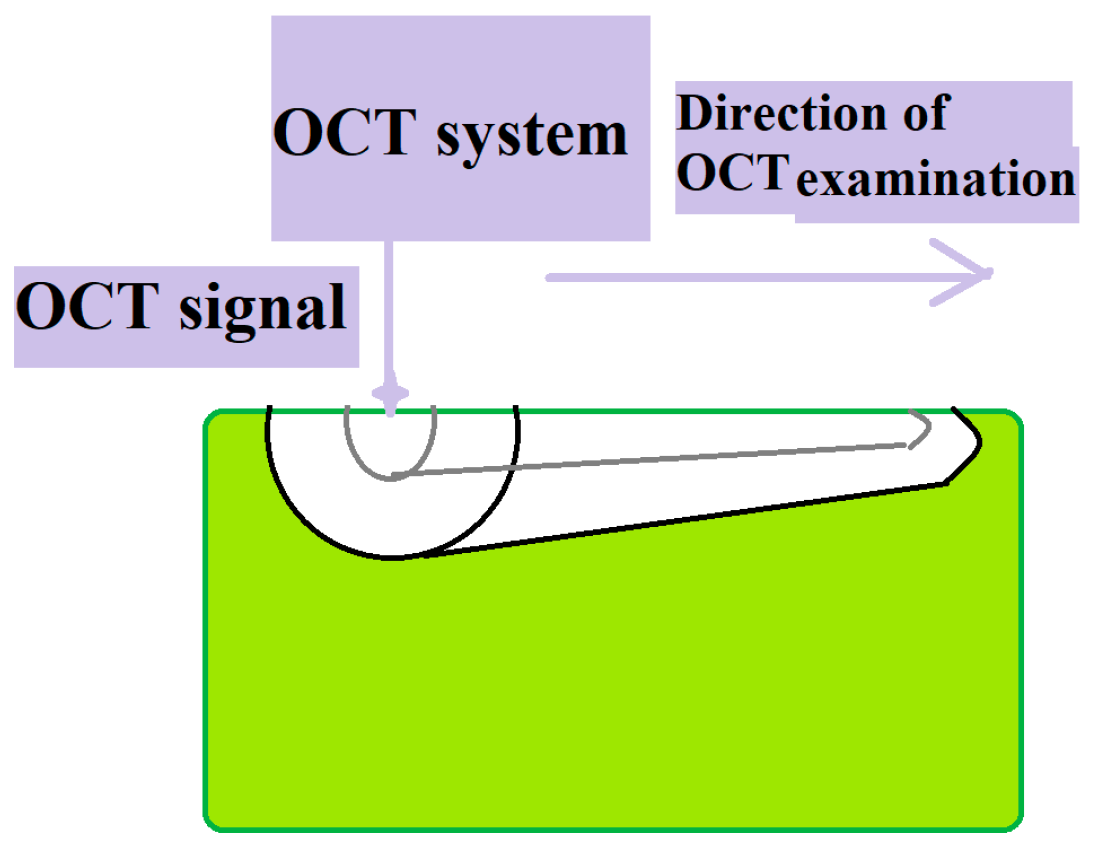

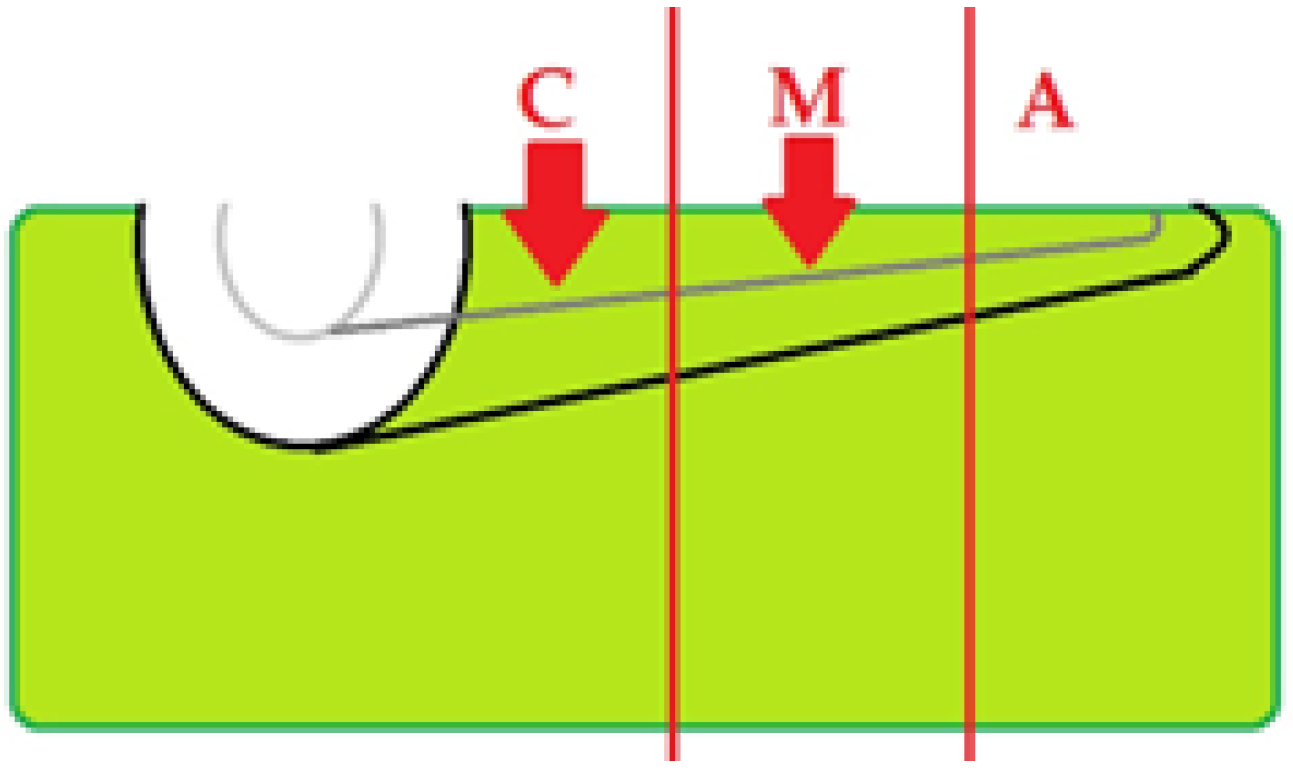

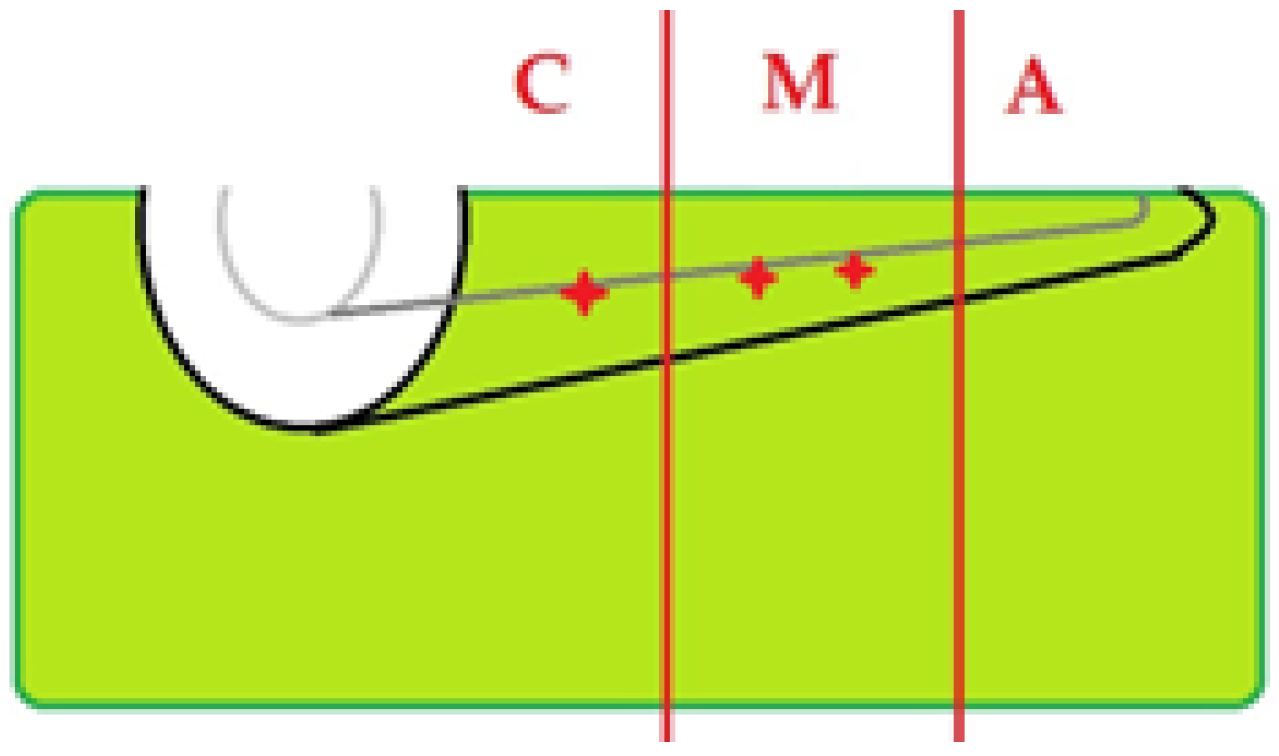

2.5. OCT Imaging Acquisition

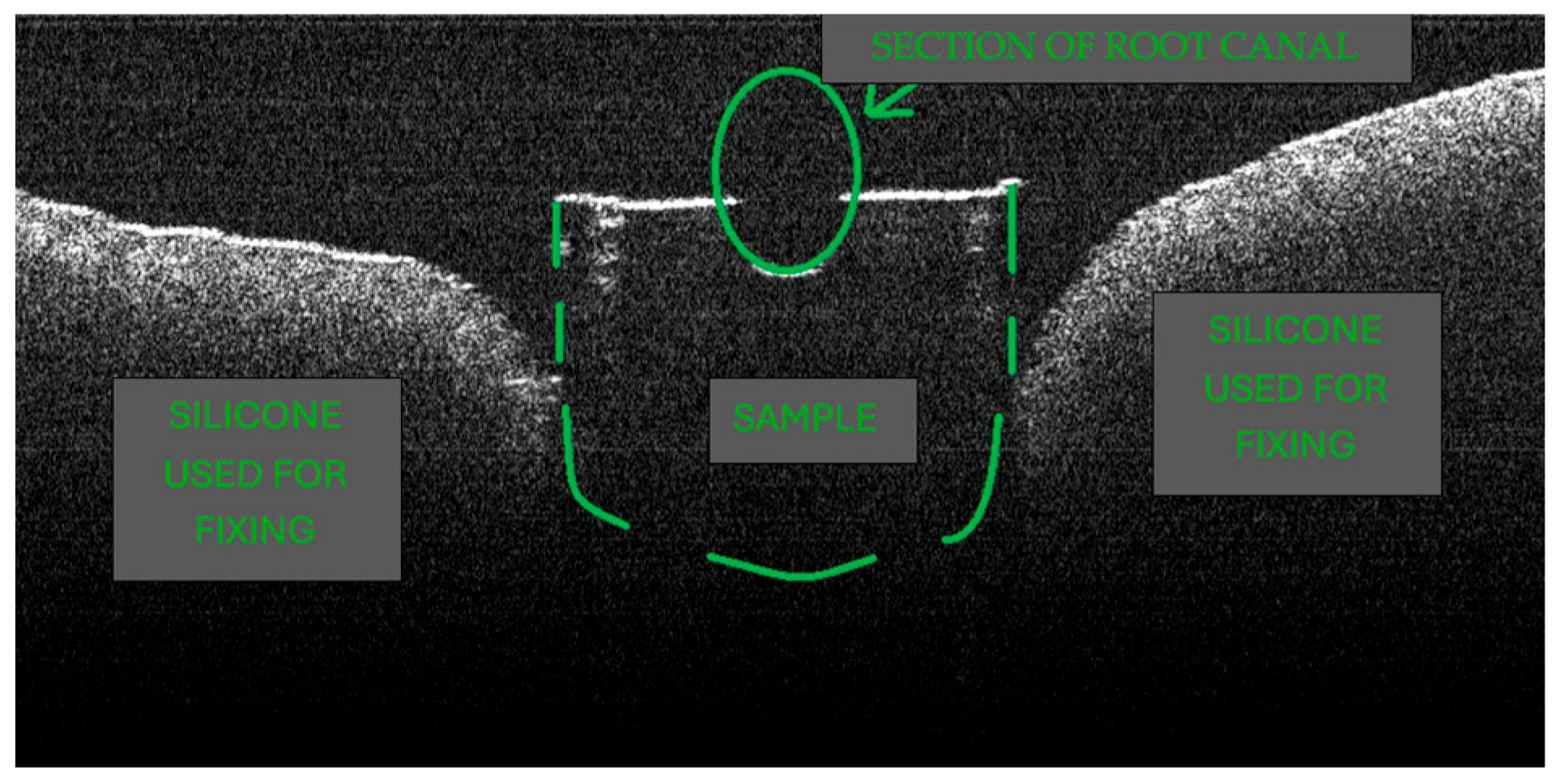

2.6. Image Interpretation

2.7. Outcomes

- Primary outcome: Presence of thermally induced morphological alteration on OCT (binary, per specimen; per coronal/middle/apical third).

- Secondary outcomes: frequency and topographic distribution of alterations; qualitative pattern descriptors; agreement with stereomicroscopy findings from a prior study.

2.8. Relationship to Prior Publication and Data-Overlap Statement

2.9. Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Specimen Flow and Allocation

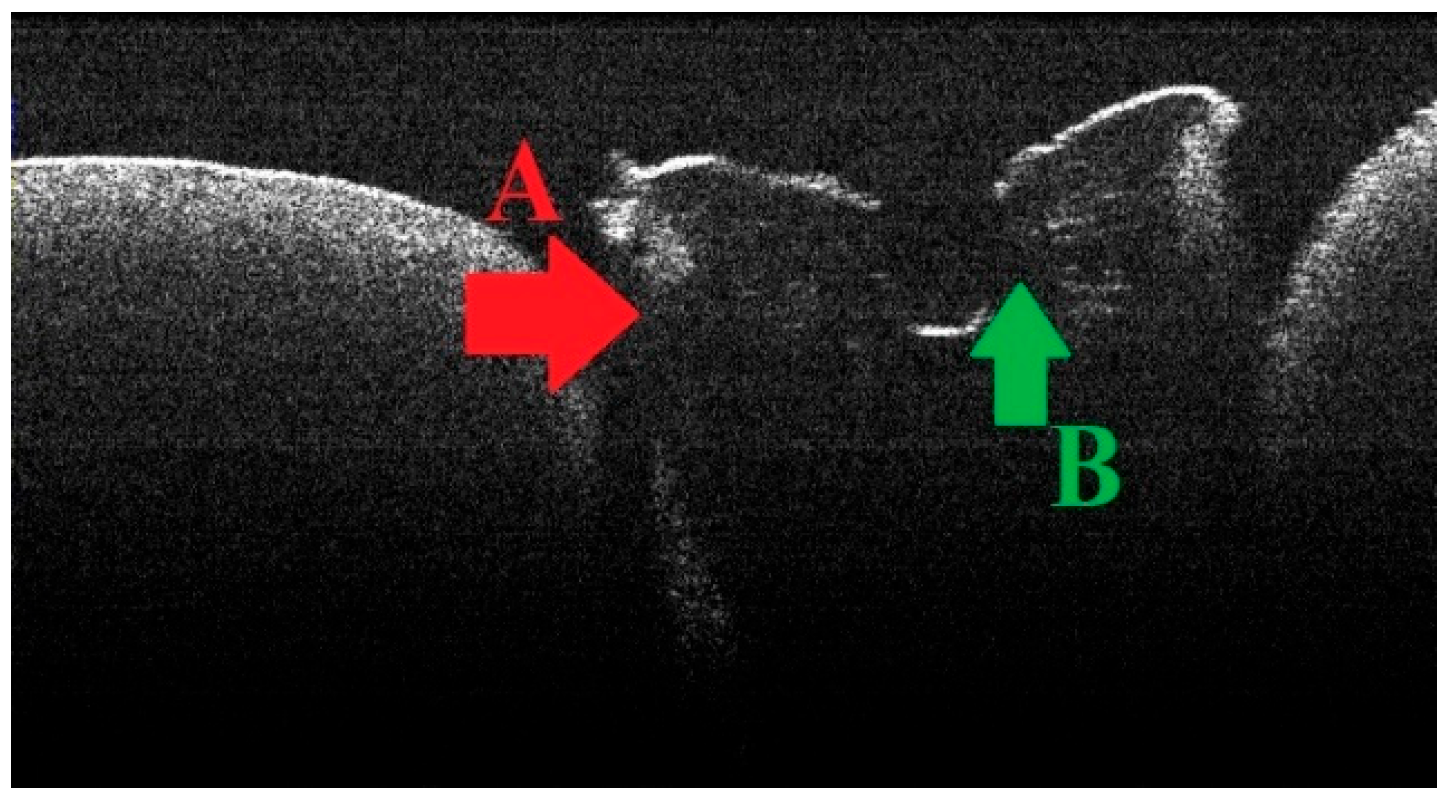

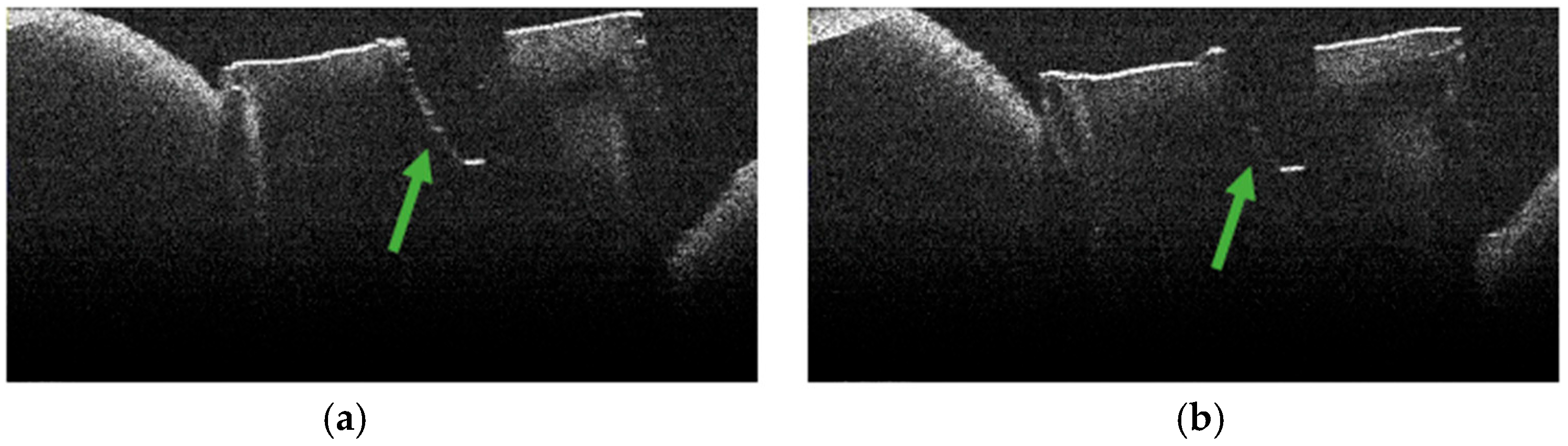

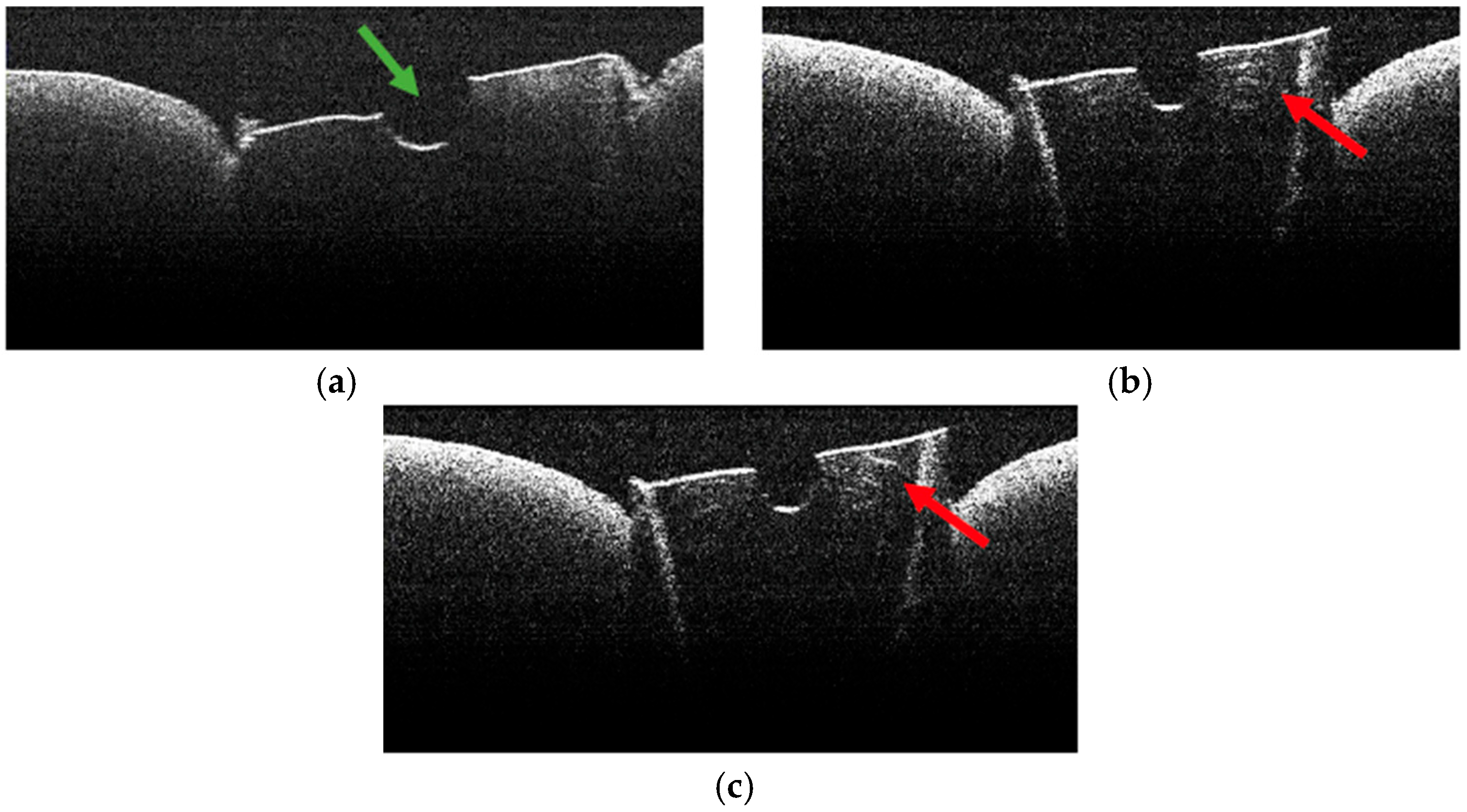

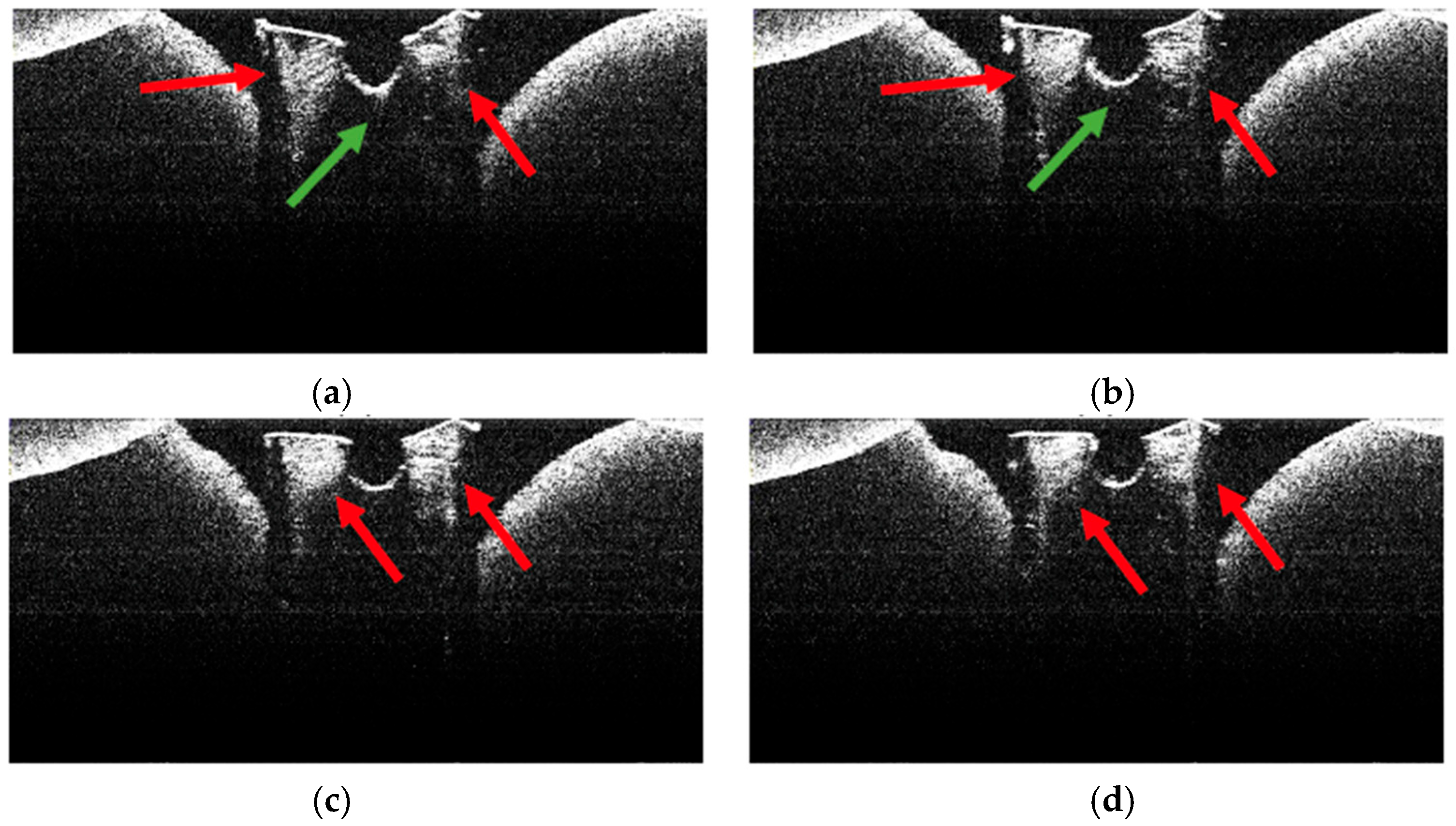

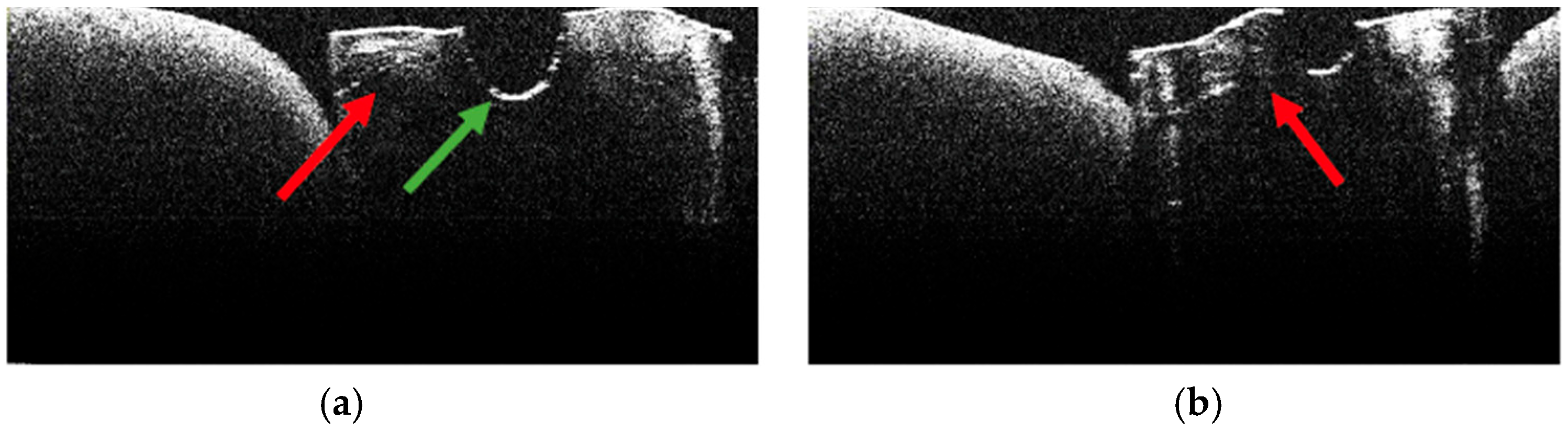

3.2. Defining OCT Signatures: Alterations vs. Artefacts

3.3. OCT Examination of Specimens from Group C

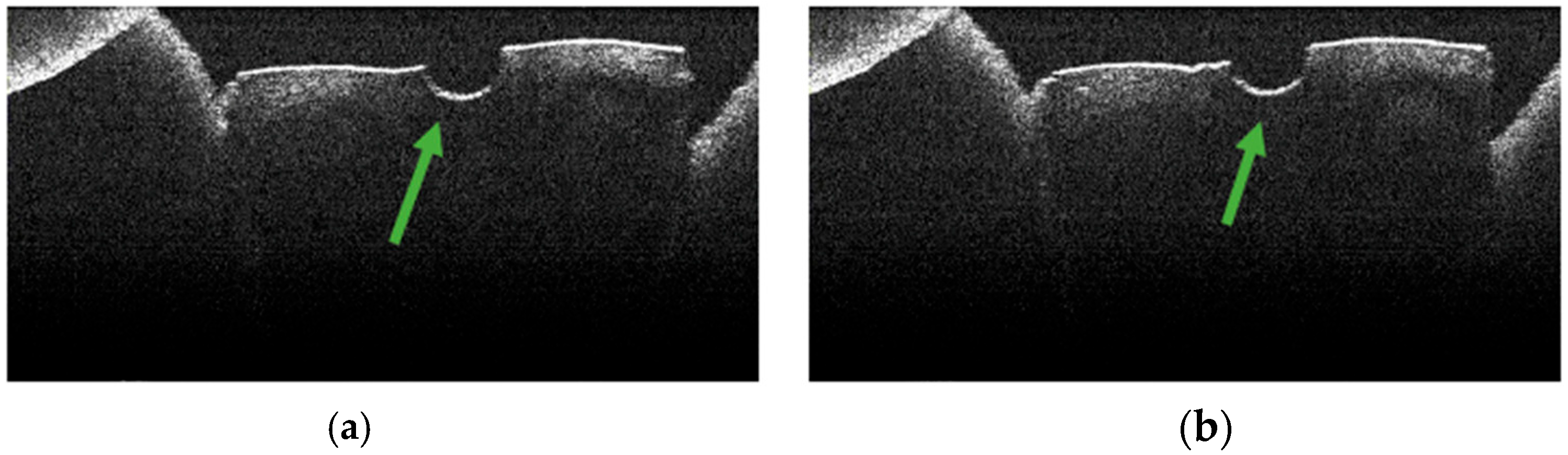

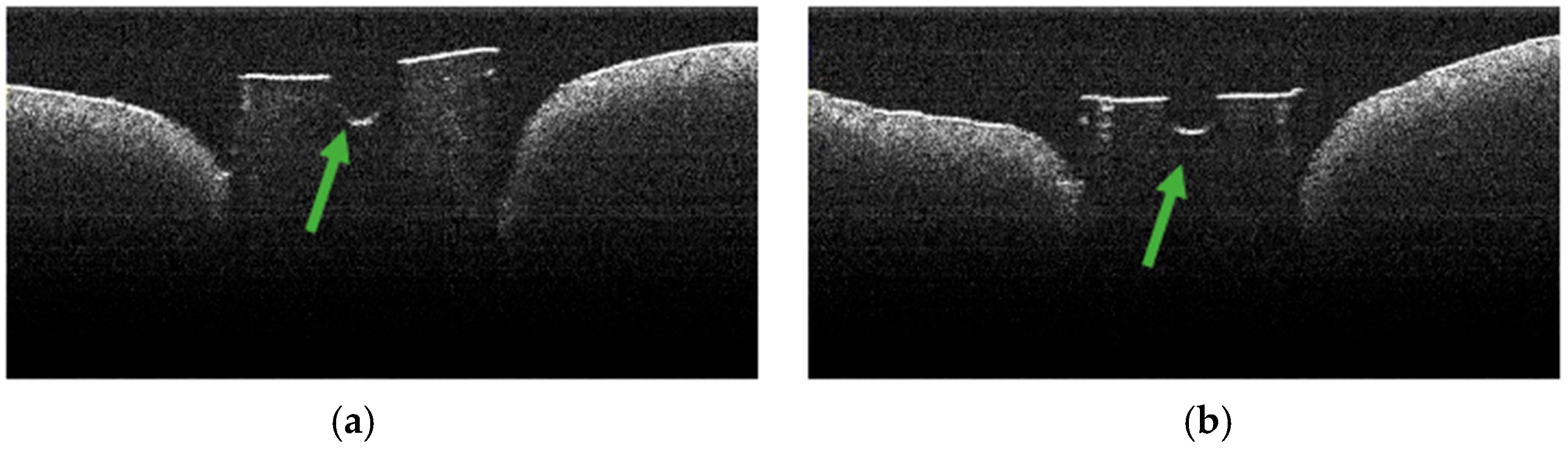

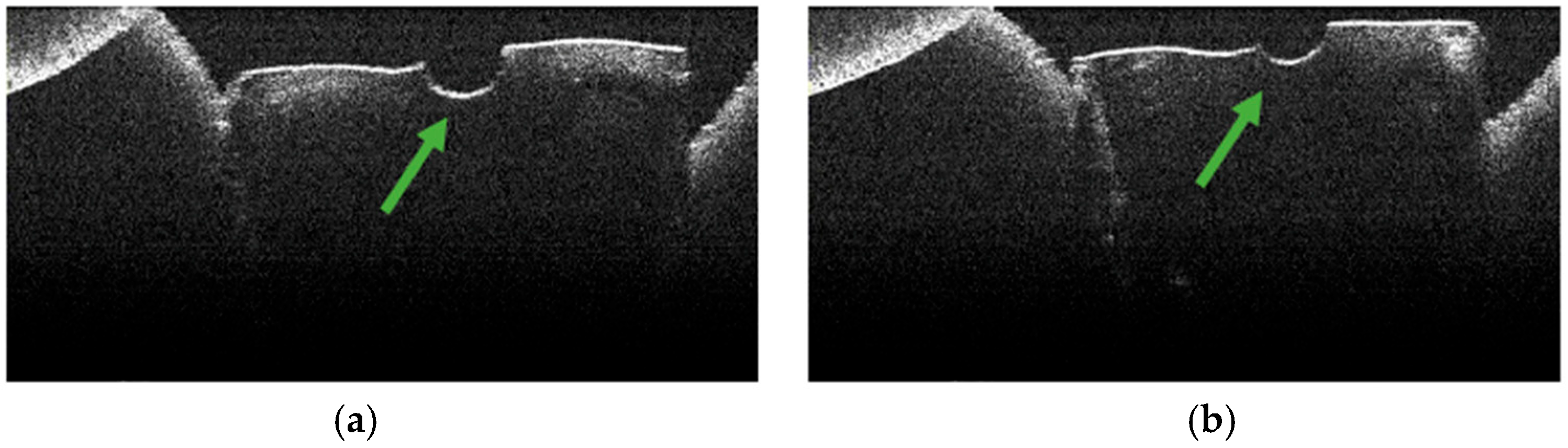

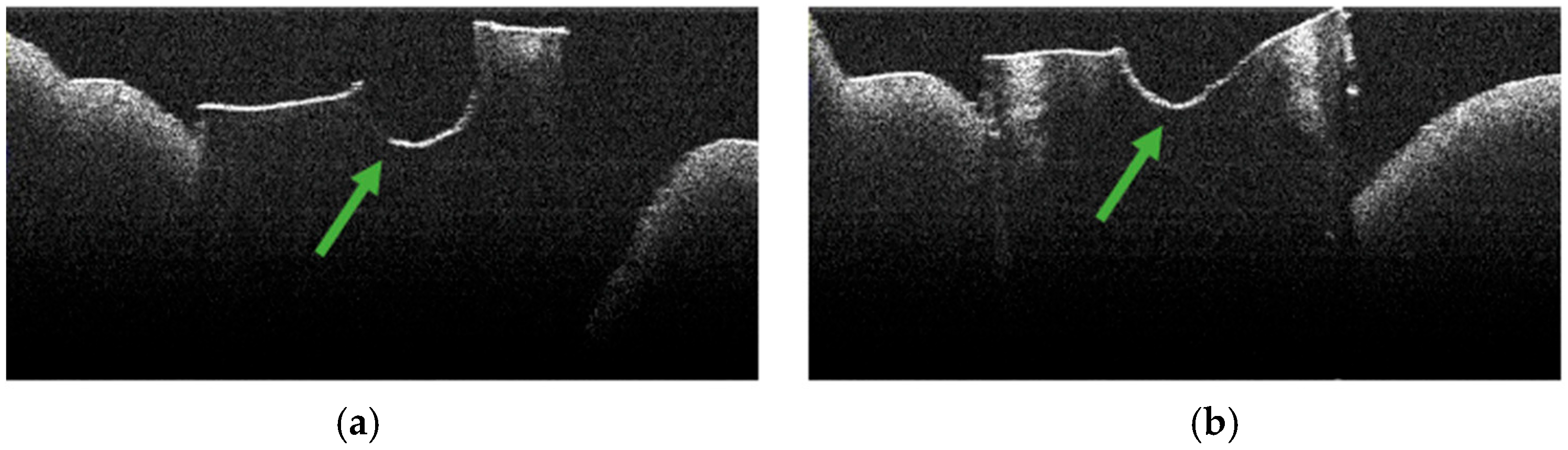

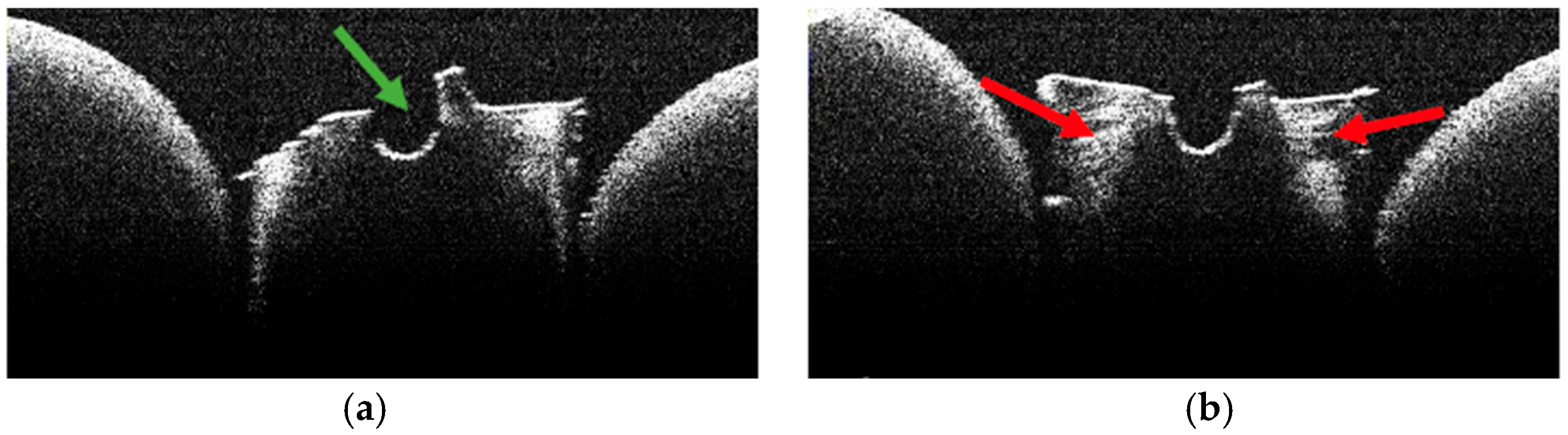

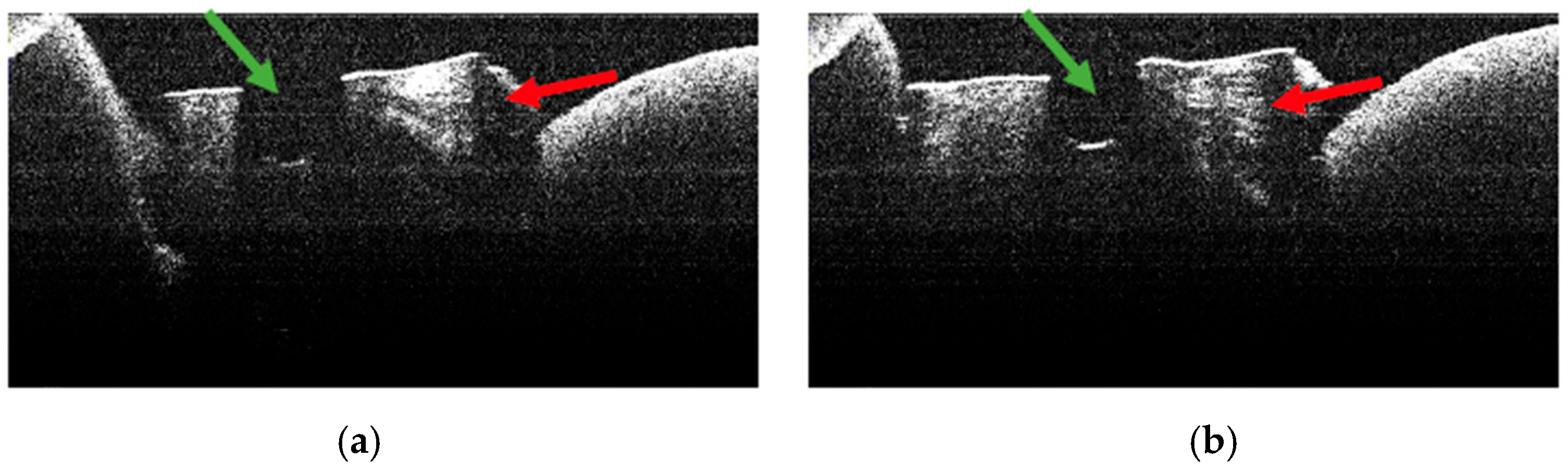

3.4. OCT Examination of Specimens from Group A

3.5. OCT Examination of Specimens from Group B

3.6. Topographic Distribution

3.7. Frequency of TIMAs

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation in Context

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| TIMAs | Thermally induced morphological alteration |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

References

- Einstein, A. Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung. Physiol. Z. 1917, 18, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, M.; AlArabi, A.A.; Turkistani, A.M.; AlSani, A.A.; Murad, G.S.; AlYami, A.S.; Masmali, A.M.; AlGhamdi, G.A.; AlJohani, E.H.; AlKhuder, M.S.; et al. The Role of Laser in Modern Dentistry: Literature Review. Ann. Dent. Spec. 2022, 10, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convissar, R.A. Principles and Practice of Laser Dentistry; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olivi, G.; De Moor, R.; Divito, E. Lasers in Endodontics—Scientific Background and Clinical Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaki, E.; Mylona, V.; Parker, S.; Lynch, E.; Grootveld, M. Systematic Review on the Role of Lasers in Endodontic Therapy: Valuable Adjunct Treatment? Dent. J. 2020, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, T.; Sezgin, G.P.; Sönmez Kaplan, S. Effect of a 980-nm diode laser on post-operative pain after endodontic treatment in teeth with apical periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wenzler, J.S.; Falk, W.; Frankenberger, R.; Braun, A. Impact of Adjunctive Laser Irradiation on the Bacterial Load of Dental Root Canals: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, S.Z.; Ghali, R.M.; Hashem, A.A.; Farid, M.M. The efficacy of 2780 nm Er,Cr;YSGG and 940 nm Diode Laser in root canal disinfection: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haidary, D.; Franzen, R.; Gutknecht, N. Root Surface Temperature Changes During Root Canal Laser Irradiation with Dual Wavelength Laser (940 and 2780 nm): A Preliminary Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănuşi, A.S.; Popa, D.L.; Ionescu, M.; Cumpătă, C.N.; Petrescu, G.S.; Ţuculină, M.J.; Dăguci, C.; Diaconu, O.A.; Gheorghiţă, L.M.; Stănuşi, A. Analysis of Temperatures Generated during Conventional Laser Irradiation of Root Canals—A Finite Element Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zand, S.A.; Al-Maliky, M.A.; Mahmood, A.S.; Al-Karadaghy, T.S. Temperature elevation investigations on the external root surface during irradiation with 940 nm diode laser in root canal treatment. Saudi Endod. J. 2018, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitic, D.; Cetenovic, B.; Jovanovic, I.; Gjorgievska, E.; Popovic, B.; Markovic, D. Diode Laser Irradiation in Endodontic Therapy through Cycles—In vitro Study. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2017, 21, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suer, K.; Ozkan, L.; Guvenir, M. Antimicrobial effects of sodium hypochlorite and Er,Cr:YSGG laser against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm. Niger. J. Clin. Pr. 2020, 23, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, S.; Vaswani, S.D.; Najan, H.B.; Mehta, D.L.; Kamble, A.B.; Chaudhari, S.D. Scanning electron microscopic evaluation of smear layer removal at the apical third of root canals using diode laser, endo Activator, and ultrasonics with chitosan: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todea, D.C.M.; Luca, R.E.; Bălăbuc, C.A.; Miron, M.I.; Locovei, C.; Mocuţa, D.E. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the root canal morphology after Er:YAG laser irradiation. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohmmed, S.A.; Vianna, M.E.; Penny, M.R.; Hilton, S.T.; Mordan, N.; Knowles, J.C. Confocal laser scanning, scanning electron, and transmission electron microscopy investigation of Enterococcus faecalis biofilm degradation using passive and active sodium hypochlorite irrigation within a simulated root canal model. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xiang, D.; He, W.; Qiu, J.; Han, B.; Yu, Q.; Tian, Y. Bactericidal Effect of Er:YAG Laser-Activated Sodium Hypochlorite Irrigation Against Biofilms of Enterococcus faecalis Isolate from Canal of Root-Filled Teeth with Periapical Lesions. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Shen, Y.; Lin, J.; Haapasalo, M. In Vitro Efficacy of XP-endo Finisher with 2 Different Protocols on Biofilm Removal from Apical Root Canals. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, B.; Gehlot, P.M.; Manjunath, M.K. Comparison of the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Octenidine Dihydrochloride and Chlorhexidine with and Without Passive Ultrasonic Irrigation—An Invitro Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZC71–ZC77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golob, B.S.; Olivi, G.; Vrabec, M.; El Feghali, R.; Parker, S.; Benedicenti, S. Efficacy of Photon-induced Photoacoustic Streaming in the Reduction of Enterococcus faecalis within the Root Canal: Different Settings and Different Sodium Hypochlorite Concentrations. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, J.; Fong, H.; Jewett, A.; Johnson, J.D.; Paranjpe, A. Disinfection Efficacy of Current Regenerative Endodontic Protocols in Simulated Necrotic Immature Permanent Teeth. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănuşi, A.; Iacov-Crăițoiu, M.M.; Scrieciu, M.; Mitruț, I.; Firulescu, B.C.; Boțilă, M.R.; Vlăduțu, D.E.; Stănuşi, A.Ş.; Mercuț, V.; Osiac, E. Morphological and Optical Coherence Tomography Aspects of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ţogoe, M.M.; Crăciunescu, E.L.; Topală, F.I.; Sinescu, C.; Nica, L.M.; Ioniţă, C.; Duma, V.F.; Romînu, M.; Podoleanu, A.G.; Negruţiu, M.L. Endodontic fillings evaluated using en face OCT, microCT and SEM. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2021, 62, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Togoe, M.M.; Cojocariu, A.C.; Modiga, C.; Sinescu, C.; Duma, V.F.; Negruţiu, M.L. Modern approaches of analysis and treatment of endodontic lesions using the endoscope and the optical coherence tomography. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 11, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, B.P.; Câmara, A.C.; Duarte, D.A.; Gomes, A.S.L.; Heck, R.J.; Antonino, A.C.D.; Aguiar, C.M. Detection of Apical Root Cracks Using Spectral Domain and Swept-source Optical Coherence Tomography. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1148–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, E.; Mannocci, F.; Brown, J.; Wilson, R.; Patel, S. A comparison of cone beam computed tomography and periapical radiography for the detection of vertical root fractures in nonendodontically treated teeth. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, R.; Mannocci, F.; Andiappan, M.; Patel, S. Comparing the in vivo diagnostic accuracy of digital periapical radiography with cone-beam computed tomography for the detection of vertical root fracture. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, T.; Sakaue, H.; Ishimura, H.; Ebihara, A.; Suda, H.; Sumi, Y. Detection of root surface fractures with swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT). Photomed. Laser Surg. 2013, 31, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shemesh, H.; van Soest, G.; Wu, M.K.; van der Sluis, L.W.; Wesselink, P.R. The ability of optical coherence tomography to characterize the root canal walls. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrutiu, M.L.; Sinescu, C.; Topala, F.I.; Nica, L.; Ionita, C.; Marcauteanu, C.; Goguta, L.; Bradu, A.; Dobre, G.; Rominu, M.; et al. Root canal filling evaluation using optical coherence tomography. In Proceedings of the Biophotonics: Photonic Solutions for Better Health Care, Brussels, Belgium, 12–16 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Todea, C.; Balabuc, C.; Sinescu, C.; Filip, L.; Kerezsi, C.; Calniceanu, M.; Negrutiu, M.; Bradu, A.; Hughes, M.; Podoleanu, A.G. En face optical coherence tomography investigation of apical microleakage after laser-assisted endodontic treatment. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrutiu, M.L.; Sinescu, C.; Hughes, M.; Bradu, A.; Todea, C.; Balabuc, C.I.; Filip, L.M.; Podoleanu, A.G. Root canal filling evaluation using optical coherence tomography. In Biophotonics: Photonic Solutions for Better Health Care; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2008; p. 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănuşi, A.Ş.; Stănuşi, A.; Gîngu, O.; Diaconu, O.A.; Ţuculină, J.M.; Cumpătă, N.C. Stereomicroscopic Aspects of Root Canal Walls after Conventional Laser Endodontics—A preliminary study. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 16, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, H.; Naz, F.; Hasan, A.; Tanwir, A.; Shahnawaz, D.; Wahid, U.; Irfan, F.; Ahmed, M.A.; Almadi, K.H.; Alkahtany, M.F.; et al. Exploring the Most Effective Apical Seal for Contemporary Bioceramic and Conventional Endodontic Sealers Using Three Obturation Techniques. Medicina 2023, 59, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Corrales, A.; Rizcala-Orlando, Y.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Volland, G.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Serrera-Figallo, M.A. Comparison of diode laser—Oral tissue interaction to different wavelengths. In vitro study of porcine periodontal pockets and oral mucosa. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2020, 25, e224–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bago, I.; Sandrić, A.; Beljic-Ivanovic, K.; Pažin, B. Influence of irrigation and laser assisted root canal disinfection protocols on dislocation resistance of a bioceramic sealer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, F.; Farmakis, E.T.; Kopic, J.; Kurzmann, C.; Moritz, A. Temperature Development on the External Root Surface During Laser-Assisted Endodontic Treatment Applying a Microchopped Mode of a 980 nm Diode Laser. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmud, R.; Kahler, W.A.; Walsh, L.J. Temperature changes accompanying near infrared diode laser endodontic treatment of wet canals. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Kinoshita, J.; Ishizaki, N.T.; Matsumoto, K. Effects of diode laser irradiation on smear layer removal from root canal walls and apical leakage after obturation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2005, 20, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, N.; Hayashi, J.I.; Fujita, M.; Iwamura, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Goto, R.; Ohno, T.; Nishida, E.; Yamamoto, G.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. Photodynamic Inactivation of an Endodontic Bacteria Using Diode Laser and Indocyanine Green-Loaded Nanosphere. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walling, J.; Kirchhoff, T.; Berthold, M.; Wenzler, J.S.; Braun, A. Impact of thermal photodynamic disinfection on root dentin temperature in vitro. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karadaghi, T.S.; Gutknecht, N.; Jawad, H.A.; Vanweersch, L.; Franzen, R. Evaluation of Temperature Elevation During Root Canal Treatment with DualWavelength Laser: 2780 nm Er,Cr:YSGG and 940 nm Diode. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Fonseca Alvarez, A.; Moura-Netto, C.; Daliberto Frugoli, A.; Fernando, C.; Aranha, A.C.; Davidowicz, H. Temperature changes on the root surfaces of mandibular incisors after an 810-nm high-intensity intracanal diode laser irradiation. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayoshi, M.; Nishihara, T.; Nakashima, K.; Iwaki, S.; Chen, K.K.; Terashita, M.; Kitamura, C. Bactericidal Effects of Diode Laser Irradiation on Enterococcus faecalis Using Periapical Lesion Defect Model. ISRN Dent. 2011, 2011, 870364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alfredo, E.M.M.; Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Brugnera-Junior, A.; Silva-Sousa, Y.T.C. Temperature variation at the external root surface during 980-nm diode laser irradiation in the root canal. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Ribeiro, A.; Nogueira, G.E.; Antoniazzi, J.H.; Moritz, A.; Zezell, D.M. Effects of diode laser (810 nm) irradiation on root canal walls: Thermographic and morphological studies. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, D.J.; Parke, S.P.A. Lasers in Dentistry–Current Concepts; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Specimens with TIMA |

|---|---|

| 1 | M3-b |

| 2 | M9-b |

| 3 | M11-a |

| 4 | M15-b |

| No. | Specimens with TIMA |

|---|---|

| 1 | M16-a |

| 2 | M16-b |

| 3 | M17-a |

| 4 | M18-a |

| 5 | M19-a |

| 6 | M19-b |

| 7 | M20-a |

| 8 | M20-b |

| 9 | M22-b |

| 10 | M23-a |

| 11 | M23-b |

| 12 | M24-b |

| 13 | M25-a |

| 14 | M25-b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stănuşi, A.Ş.; Diaconu, O.A.; Stănuşi, A.; Osiac, E.; Brătoiu, M.R.; Petrescu, G.-S.; Bugălă, A.S.; Dimitriu, B.; Ţuculină, M.J. Depth-Resolved OCT of Root Canal Walls After Diode-Laser Irradiation: A Descriptive Ex Vivo Study Following a Stereomicroscopy Report. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233083

Stănuşi AŞ, Diaconu OA, Stănuşi A, Osiac E, Brătoiu MR, Petrescu G-S, Bugălă AS, Dimitriu B, Ţuculină MJ. Depth-Resolved OCT of Root Canal Walls After Diode-Laser Irradiation: A Descriptive Ex Vivo Study Following a Stereomicroscopy Report. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233083

Chicago/Turabian StyleStănuşi, Adrian Ştefan, Oana Andreea Diaconu, Andreea Stănuşi, Eugen Osiac, Mihaela Roxana Brătoiu, Gabriel-Sebastian Petrescu, Adelina Smaranda Bugălă, Bogdan Dimitriu, and Mihaela Jana Ţuculină. 2025. "Depth-Resolved OCT of Root Canal Walls After Diode-Laser Irradiation: A Descriptive Ex Vivo Study Following a Stereomicroscopy Report" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233083

APA StyleStănuşi, A. Ş., Diaconu, O. A., Stănuşi, A., Osiac, E., Brătoiu, M. R., Petrescu, G.-S., Bugălă, A. S., Dimitriu, B., & Ţuculină, M. J. (2025). Depth-Resolved OCT of Root Canal Walls After Diode-Laser Irradiation: A Descriptive Ex Vivo Study Following a Stereomicroscopy Report. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233083