Digitally Guided Modified Intentional Replantation for a Tooth with Hopeless Periodontal Prognosis: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Aspects

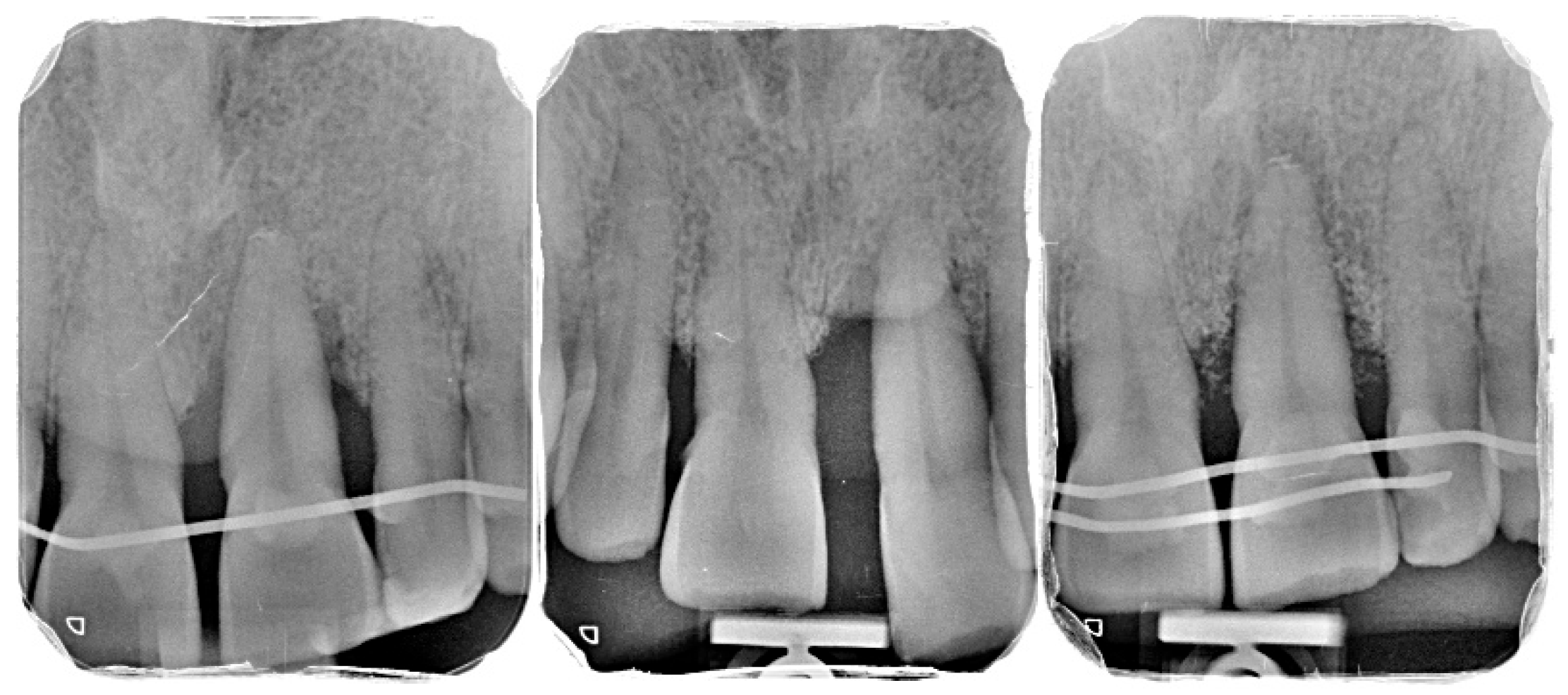

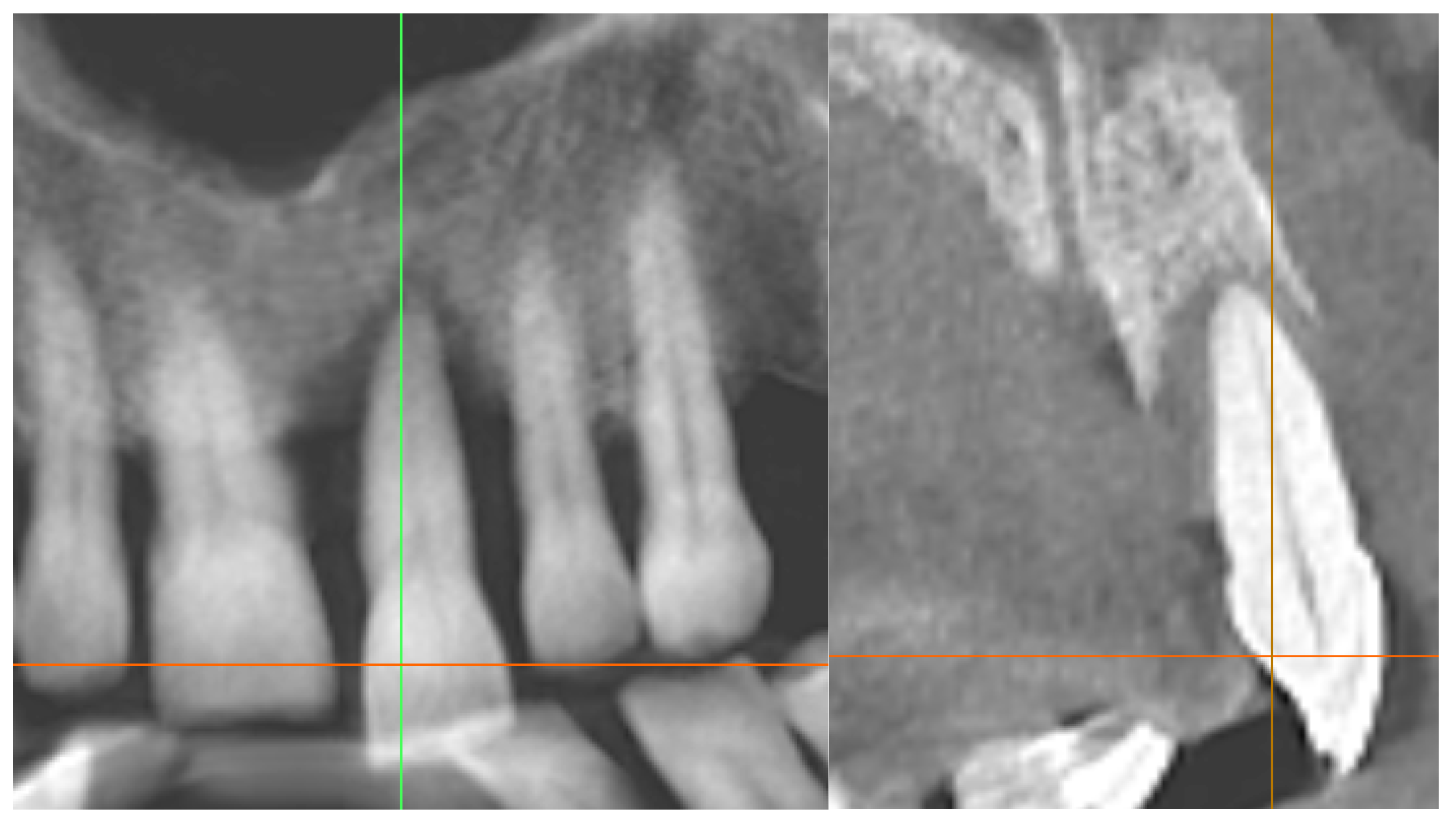

2.2. Patient Information and Periodontal Diagnosis

2.3. Initial Periodontal Therapy

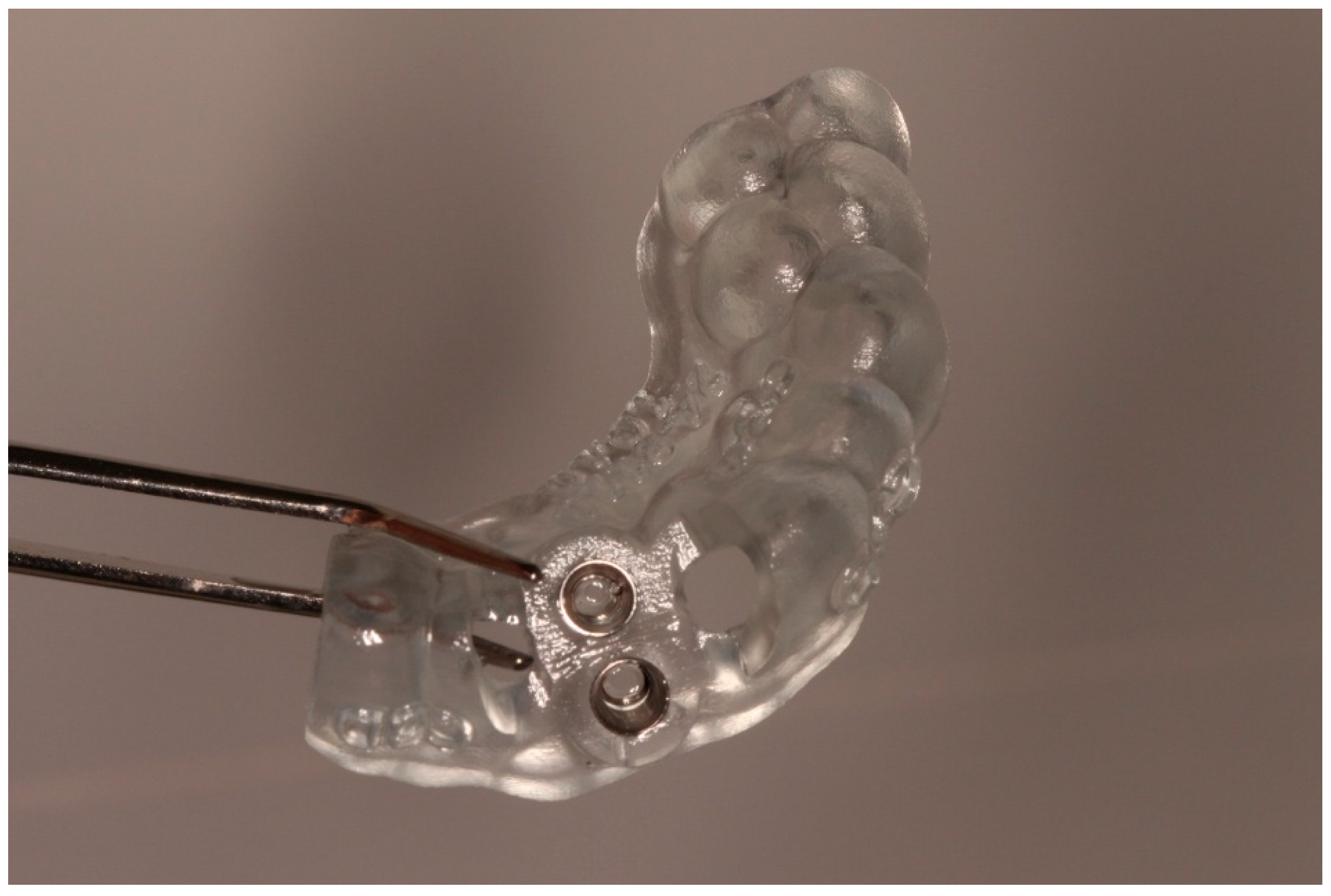

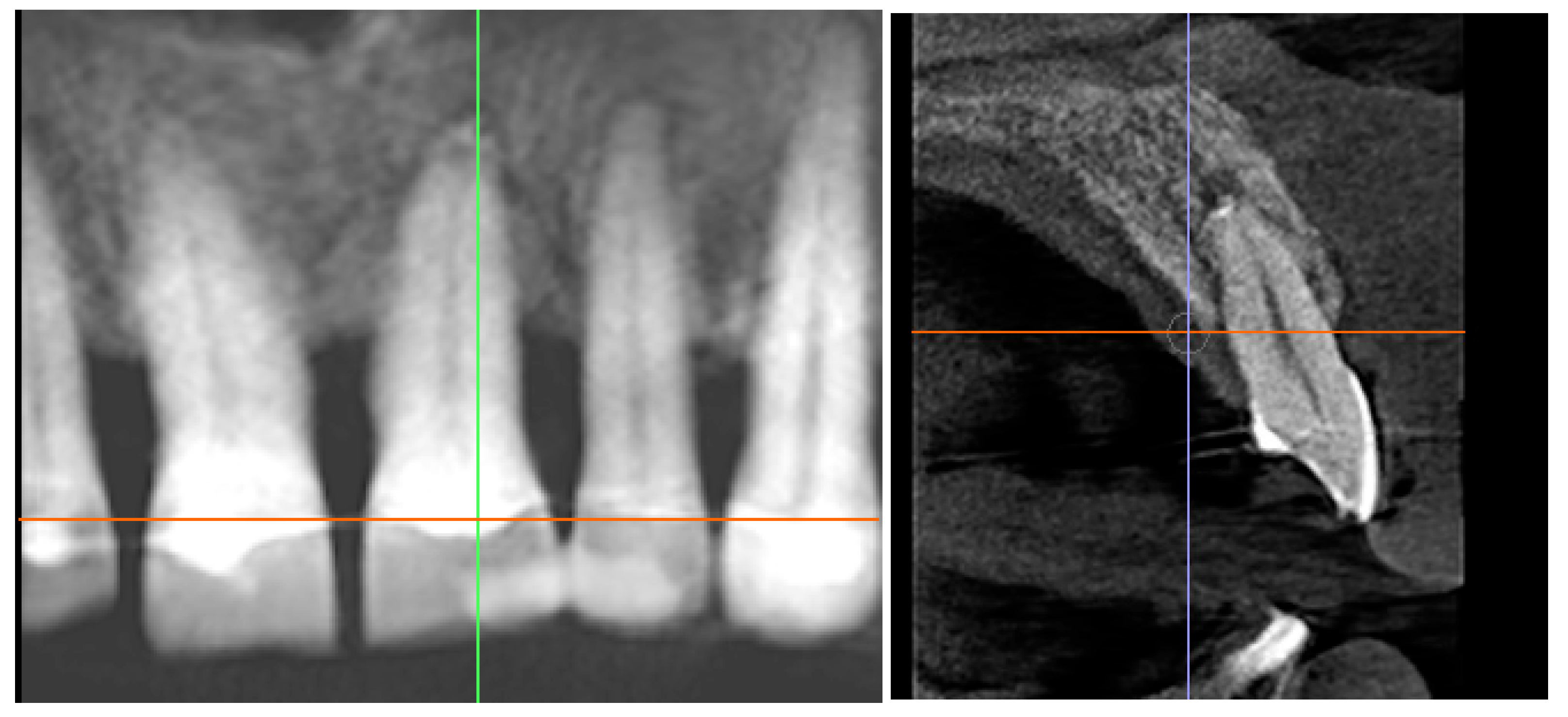

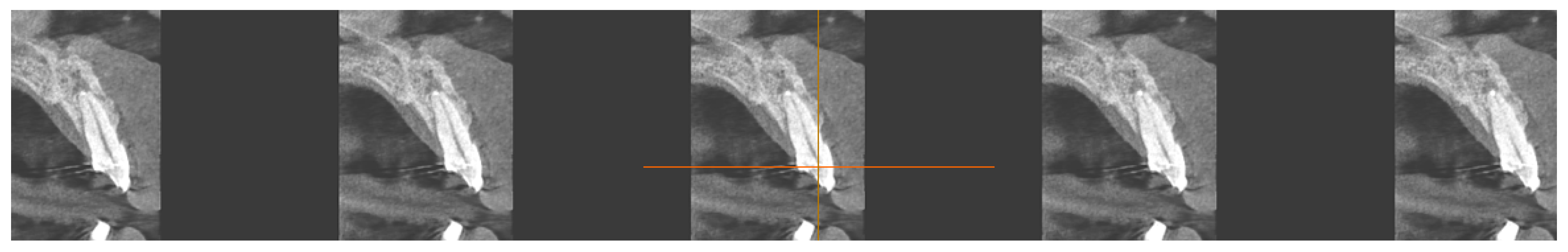

2.4. Digital Planning and Surgical Guide Fabrication

2.5. Surgical Procedure

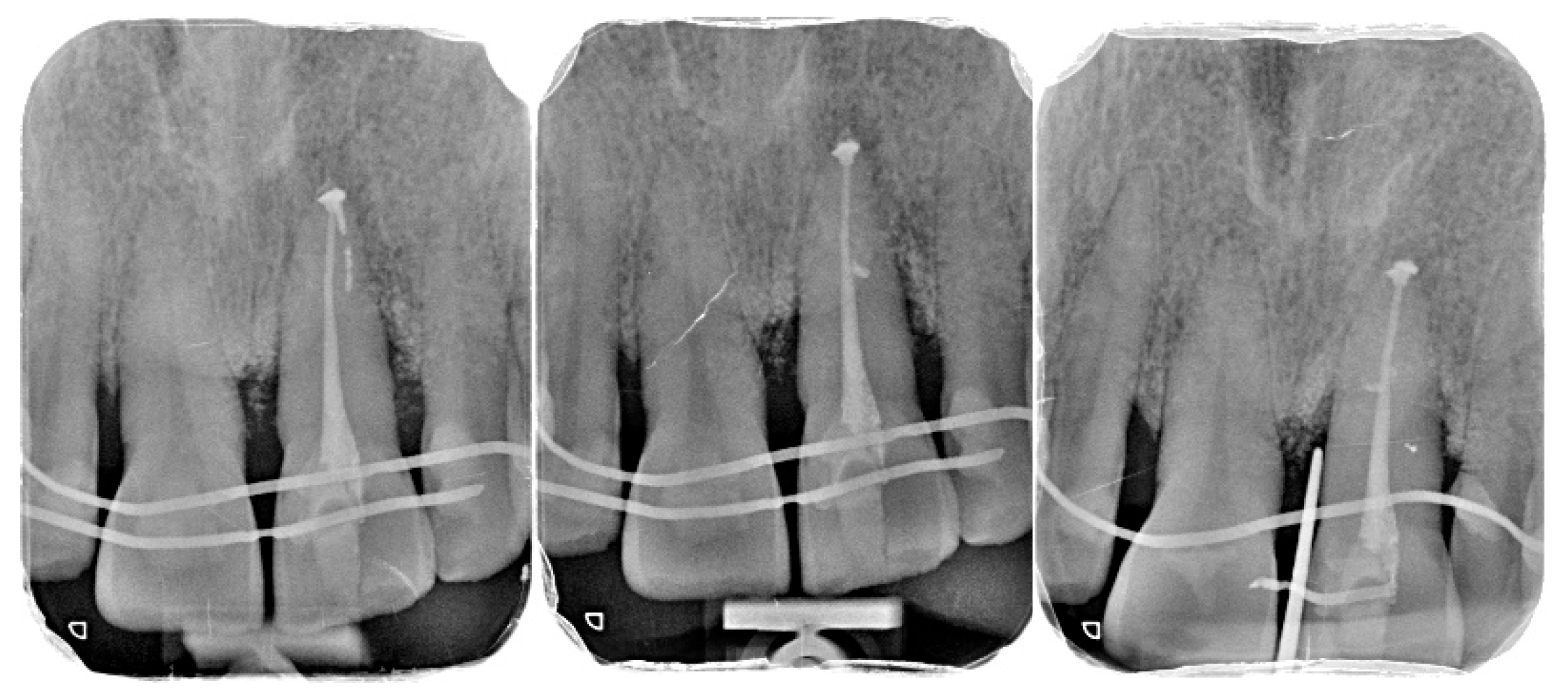

- Atraumatic extraction: Tooth 21 was carefully luxated using periotomes to preserve the PDL and surrounding bone. Immediately after extraction, the tooth was stored in chilled sterile saline (approximately 4–6 °C). The total extraoral period was approximately 10 min.

- Preparation of the recipient socket: After curettage of granulation tissue from the original socket, the CAD/CAM surgical guide was positioned. A guided osteotomy was performed using the implant-type drills from the C3D Cambados guided surgery kit, following the virtual plan. A biologic drilling protocol without irrigation was used to preserve autologous bone chips in the osteotomy walls. These chips were collected and later used as graft material. Drill sequence, diameters, and depth calibration followed the manufacturer’s recommendations and the digital plan, maintaining a stable trajectory and preserving palatal bone for primary stability.

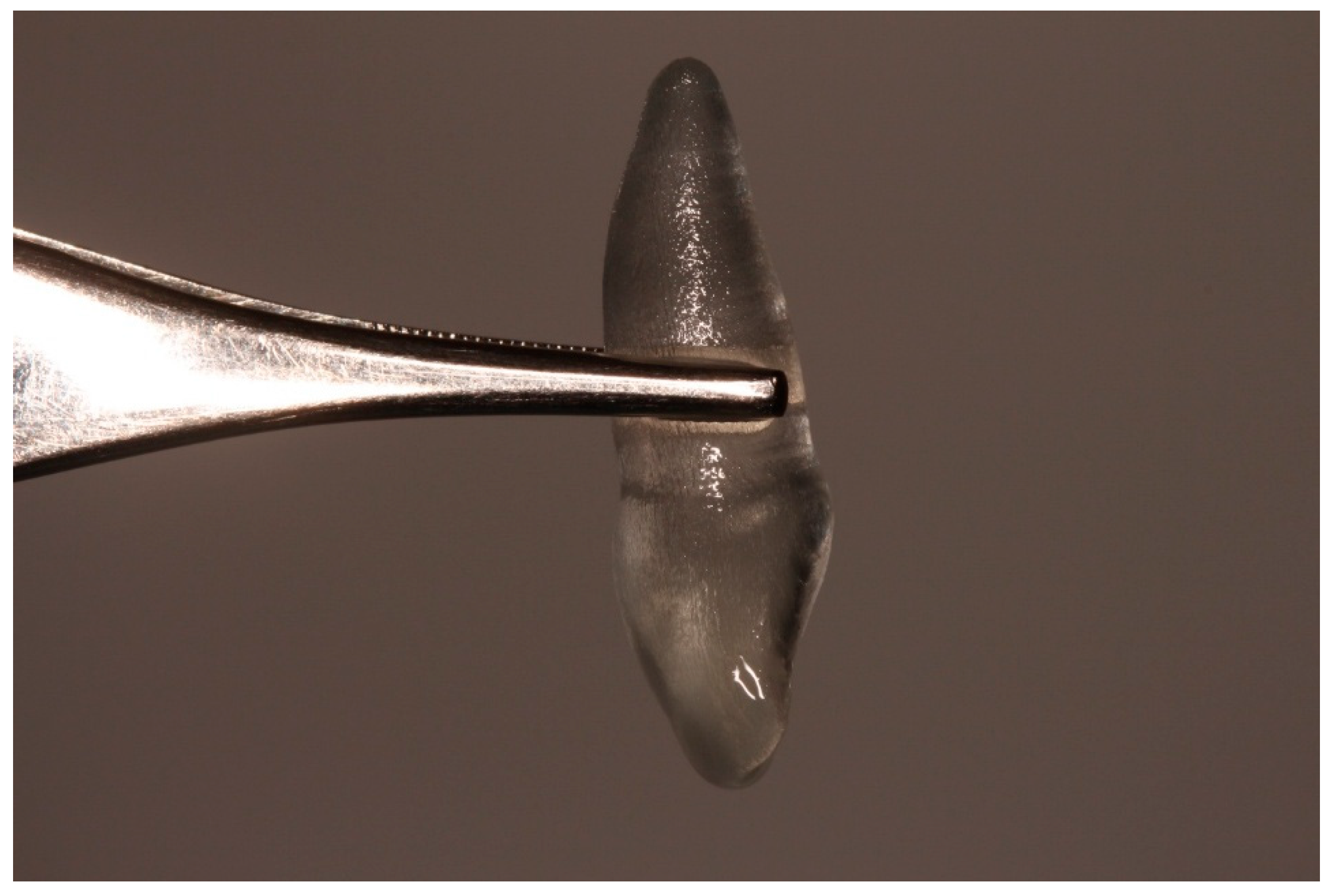

- Verification with the 3D-printed replica: The printed tooth replica was inserted into the prepared socket to confirm angulation and depth prior to replantation of the original tooth.

- Extraoral root-end management: During the extraoral phase, apicoectomy was performed, and a retrograde cavity was prepared and sealed with a bioceramic material (Biodentine®, Septodont, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France) to provide an apical barrier and reduce contamination risk.

- Replantation and splinting: The original tooth was replanted into the digitally prepared socket, achieving primary stability by adapting to the prepared walls and remaining palatal bone. A semi-rigid splint was placed using fibre-reinforced composite bonded to adjacent teeth, planned for a 4-month period.

- Guided tissue regeneration: A full-thickness flap was elevated to expose the defect morphology. Autologous bone chips collected during drilling were combined with xenograft particles (Bio-Oss®, Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) and enamel matrix derivative (Emdogain®, Straumann, Basel, Switzerland) and placed around the replanted root. A resorbable collagen membrane (Bio-Gide®, Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) was positioned to stabilize the grafted area and support space maintenance. The flap was repositioned and sutured to achieve primary closure.

2.6. Postoperative Management and Endodontic Treatment

2.7. Follow-Up and Outcome Measures

- Primary clinical outcomes included:

- Change in tooth mobility (grade III to grade 0);

- Reduction in probing pocket depth (PPD) to ≤4 mm;

- Absence of bleeding on probing or suppuration.

- Radiographic outcomes included:

- Radiographic bone fill within the original defect;

- Presence of a periodontal ligament–like space around the root;

- Absence of radiographic signs of ankylosis or root resorption.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

3.2. Radiographic Findings

3.3. Functional and Aesthetic Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Case Selection and Prognosis

4.2. Digital Guidance and Socket Preparation

4.3. Regenerative Approach and Endodontic Protocol

4.4. Comparison with Implant-Based Rehabilitation

4.5. Interpretation of Regenerative Outcomes

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L. GBD 2021 Collaborators. Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2259–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Smith, A.G.C.; Bernabé, E.; Fleming, T.D.; Reynolds, A.E.; Vos, T.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W. GBD 2015 Oral Health Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, L.; Aris, I.M. Minimal changes in daily flossing behavior among US adults from 2009 through 2020. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 155, 587–596.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offenbacher, S.; Barros, S.P.; Singer, R.E.; Moss, K.; Williams, R.C.; Beck, J.D. Periodontal disease at the biofilm-gingival interface. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lindhe, J.; Lang, N.P.; Karring, T. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, 5th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, M.K. Prognosis versus actual outcome: A long-term survey of 100 treated periodontal patients. J. Periodontol. 1991, 62, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFP Clinical Guidelines. Guideline on Treatment of Stage I-III Periodontitis. Available online: https://www.efp.org/education/continuing-education/clinical-guidelines/guideline-on-treatment-of-stage-i-iii-periodontitis/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Jepsen, K.; Sculean, A.; Jepsen, S. Complications and treatment errors related to regenerative periodontal surgery. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 92, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M.Y.; Ozasa, R.; Ishimoto, T.; Nakano, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Kashiwagi, M.; Yamanaka, S.; Nakao, K.; Maruyama, H.; Bessho, K.; et al. Periodontal Tissue as a Biomaterial for Hard-Tissue Regeneration following bmp-2 Gene Transfer. Materials 2022, 15, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Jong, T.; Bakker, A.D.; Everts, V.; Smit, T.H. The intricate anatomy of the periodontal ligament and its development. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimetti, M.; Stasikelyte, M.; Mariani, G.M.; Cricenti, L.; Baima, G.; Romano, F. The flapless approach with and without enamel matrix derivatives. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, J.; Niemczyk, W.; Dominiak, M.; Niemczyk, S.; Wiench, R.; Skaba, D. Gingival Augmentation Using Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (i-PRF)-A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehta, V.; Kaçani, G.; Moaleem, M.M.A.; Almohammadi, A.A.; Alwafi, M.M.; Mulla, A.K.; Alharbi, S.O.; Aljayyar, A.W.; Qeli, E.; Toti, Ç.; et al. Hyaluronic Acid: A New Approach for the Treatment of Gingival Recession-A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tomokiyo, A.; Wada, N.; Maeda, H. Periodontal ligament stem cells: Regenerative potency. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, M.; Tsukiboshi, C.; Levin, L. A step-by-step guide for autotransplantation of teeth. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39 (Suppl. S1), 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cheng, L.; Deng, X.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, W.; Zeng, W.; Tang, W.; Liu, C. Prognosis of intentional replantation for periapical periodontitis teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ji, H.; Ren, L.; Han, J.; Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ge, X.; Meng, X.; Yu, F. Tooth autotransplantation gives teeth a second chance at life: A case series. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meinzer, S.; Nolte, D.; Huth, K.C. Autogenous Tooth Transplantation of Canines-A Prospective Clinical Study on the Influence of Adjunctive Antibiosis and Patient-Related Risk Factors During Initial Healing. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shahbazian, M.; Jacobs, R.; Wyatt, J.; Willems, G.; Pattijn, V.; Dhoore, E.; Van Lierde, C.; Vinckier, F. Accuracy and surgical feasibility of a CBCT-based stereolithographic surgical guide aiding autotransplantation of teeth: In vitro validation. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Álvarez, J.; Riad-Deglow, E.; Quispe-López, N.; Rico-Romano, C.; Zubizarreta-Macho, A. Technology at the service of surgery in a new technique of autotransplantation by guided surgery: A case report. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, D.; Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Qiu, L.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Expert consensus on intentional tooth replantation. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, M.; Zhou, L. Fully guided system for position-predictable autotransplantation of teeth: A randomized clinical trial. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 58, 550–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Du, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yue, L.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; Chen, Z.; Liang, J.; Chen, W.; Qiu, L.; et al. Expert consensus on digital guided therapy for endodontic diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacobs, R.; Fontenele, R.C.; Lahoud, P.; Shujaat, S.; Bornstein, M.M. Radiographic diagnosis of periodontal diseases—Current evidence versus innovations. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 95, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziani, F.; Izzetti, R.; Perić, M.; Marhl, U.; Nisi, M.; Gennai, S. Early periodontal wound healing after chlorhexidine rinsing: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, R.X.; Xu, B.H. Safety and Efficacy of Midface Augmentation Using Bio-Oss Bone Powder and Bio-Gide Collagen Membrane in Asians. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Zafar, M.S.; Alnazzawi, A. Comparing Nanohydroxyapatite Graft and Other Bone Grafts in the Repair of Periodontal Infrabony Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasuike, A.; Watanabe, T.; Hirooka, A.; Arai, S.; Akutagawa, H.; Yoshinuma, N.; Sato, S. Enamel matrix derivative monotherapy versus combination therapy with bone grafts for periodontal intrabony defects: An updated review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2024, 60, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yarkac, F.U.; Tassoker, M.; Atay, U.T.; Azman, D. Evaluation of trabecular bone in individuals with periodontitis using fractal analysis: An observational cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2023, 15, e1022–e1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, A.; Pitta, J.; Panadero, R.A.; Chantler, J.G.M.; Villar, S.F.; Fonseca, M.; Gil Lozano, J.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Hey, J.; Karasan, D.; et al. Rehabilitation Strategies and Occlusal Vertical Dimension Considerations in the Management of Worn Dentitions: Consensus Statement From SSRD, SEPES, and PROSEC Conference on Minimally Invasive Restorations. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2025, 37, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khojaste, M.; Navabi, S.; Shiezadeh, F. Treatment of a Hopeless Tooth with Combined Endodontic-periodontal Lesion Using Guided Tissue Regeneration: A Case Report with One Year Follow-up. Iran. Endod. J. 2022, 17, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hosoya, N.; Takigawa, T.; Horie, T.; Maeda, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Momoi, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Okiji, T. A review of the literature on the efficacy of mineral trioxide aggregate in conservative dentistry. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, R.J.; Moraschini, V.; Estrin, N.E.; Shibli, J.A.; Cosgarea, R.; Jepsen, K.; Jervøe-Storm, P.; Sculean, A.; Jepsen, S. Periodontal regeneration using platelet-rich fibrin. Furcation defects: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Periodontol. 2000 2025, 97, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, Y.; Hosseinpour, S.; Wen, J.; Peters, O.A. In Vitro Bioactivity and Cytotoxicity Assessment of Two Root Canal Sealers. Materials 2025, 18, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bali, V.; Gupta, G.; Parimoo, R.; Zarabi, M.; Tuteja, S.; Gupta, S. Emdogain In The Regeneration Of Periodontal Tissues: A 6-Month Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2025, 24, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Luan, X.; Liu, X. Recent advances in periodontal regeneration: A biomaterial perspective. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Owens, D.; Watkinson, S.; Harrison, J.E.; Turner, S.; Worthington, H.V. Orthodontic treatment for prominent lower front teeth (Class III malocclusion) in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD003451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tso, K.Y.; Chiu, W.C.; Wu, Y.H. Assessing the impact of apicoectomy on autotransplantation success rates: A six-year retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 20, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suwanapong, T.; Waikakul, A.; Boonsiriseth, K.; Ruangsawasdi, N. Pre- and peri-operative factors influence autogenous tooth transplantation healing in insufficient bone sites. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matarasso, M.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Blasi, A.; Ramaglia, L.; Salvi, G.E.; Sculean, A. Enamel matrix derivative and bone grafts for periodontal regeneration of intrabony defects. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Tietmann, C.; Wenzel, S.; Luengo, M.; Gaveglio, L.; Cardaropoli, D.; Kutschera, E.; Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Wüllenweber, P.; Jepsen, S.; et al. RCT on orthodontic timing post-periodontal regeneration: Root resorption and tooth movement outcomes. Eur. J. Orthod. 2025, 47, cjaf078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cui, W.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, H. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of Bio-Oss granules and Bio-Oss Collagen in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects: A retrospective cohort study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2024, 32, e20230268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dosdogru, E.B.; Ziyaettin, M.; Ertürk, A.F. Investigation of the Effect of Periodontitis on Trabecular Bone Structure by Fractal Analysis. Cureus 2025, 17, e77833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palkovics, D.; Mangano, F.G.; Nagy, K.; Windisch, P. Digital three-dimensional visualization of intrabony periodontal defects for regenerative surgical treatment planning. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ashkenazi, M.; Shashua, D.; Kegen, S.; Nuni, E.; Duggal, M.; Shuster, A. Computerized three-dimensional design for accurate orienting and dimensioning artificial dental socket for tooth autotransplantation. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicilia-Pasos, J.; Kewalramani, N.; Peña-Cardelles, J.F.; Salgado-Peralvo, A.O.; Madrigal-Martínez-Pereda, C.; López-Carpintero, Á. Autotransplantation of teeth with incomplete root formation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 3795–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuesta Román, R.; López-González, Á.A.; Obrador de Hevia, J.; Arroyo Bote, S.; Paublini Oliveira, H.; Riutord-Sbert, P. Digitally Guided Modified Intentional Replantation for a Tooth with Hopeless Periodontal Prognosis: A Case Report. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3080. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233080

Cuesta Román R, López-González ÁA, Obrador de Hevia J, Arroyo Bote S, Paublini Oliveira H, Riutord-Sbert P. Digitally Guided Modified Intentional Replantation for a Tooth with Hopeless Periodontal Prognosis: A Case Report. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3080. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233080

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuesta Román, Raul, Ángel Arturo López-González, Joan Obrador de Hevia, Sebastiana Arroyo Bote, Hernán Paublini Oliveira, and Pere Riutord-Sbert. 2025. "Digitally Guided Modified Intentional Replantation for a Tooth with Hopeless Periodontal Prognosis: A Case Report" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3080. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233080

APA StyleCuesta Román, R., López-González, Á. A., Obrador de Hevia, J., Arroyo Bote, S., Paublini Oliveira, H., & Riutord-Sbert, P. (2025). Digitally Guided Modified Intentional Replantation for a Tooth with Hopeless Periodontal Prognosis: A Case Report. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3080. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233080