Predicting Bleeding in AML-Associated DIC: Limitations of the ISTH Score and a Modified Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

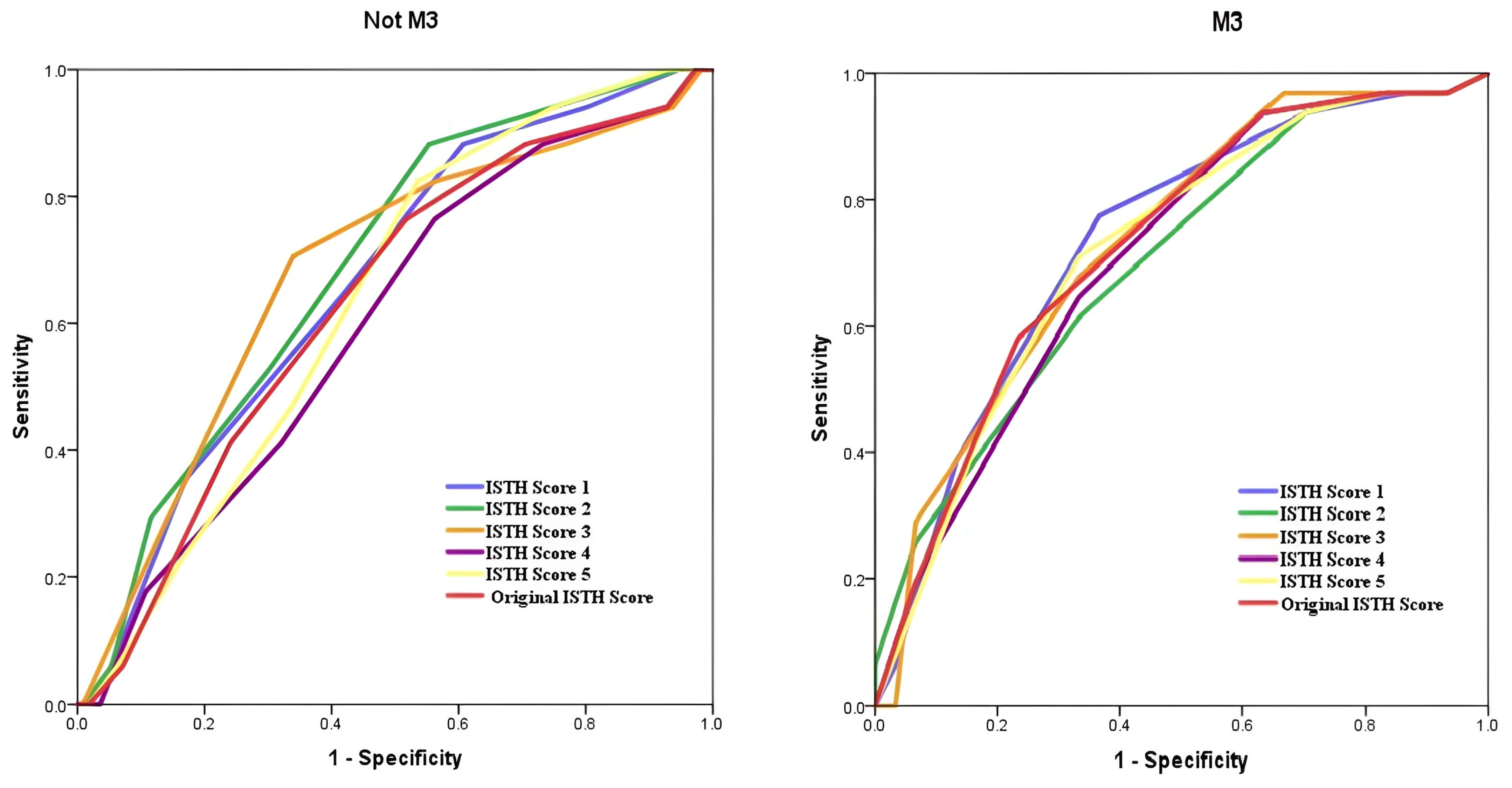

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chowdhury, M.; Begum, M.; Khan, R.; Kabir, A.; Islam, S.; Layla, K.; Ahamed, F.; Tanin, J. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation at Diagnosis in Acute Myeloblastic Leukaemia. J. Biosci. Med. 2021, 09, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Cate, H.; Leader, A. Management of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Acute Leukemias. Hamostaseologie 2021, 41, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, L. Coagulopathy in cytogenetically and molecularly distinct acute leukemias at diagnosis: Comprehensive study. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2020, 81, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.F.; Makar, R.S.; Antic, D.; Levy, J.H.; Douketis, J.D.; Connors, J.M.; Carrier, M.; Zwicker, J.I. Management of hemostatic complications in acute leukemia: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 3174–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.B., Jr.; Toh, C.H.; Hoots, W.K.; Wada, H.; Levi, M. Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb. Haemost. 2001, 86, 1327–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libourel, E.J.; Klerk, C.P.W.; van Norden, Y.; de Maat, M.P.M.; Kruip, M.J.; Sonneveld, P.; Löwenberg, B.; Leebeek, F.W.G. Disseminated intravascular coagulation at diagnosis is a strong predictor for thrombosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2016, 128, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owattanapanich, W.; Rungjirajittranon, T.; Jantataeme, A.; Kungwankiattichai, S.; Ruchutrakool, T. Simplified predictive scores for thrombosis and bleeding complications in newly diagnosed acute leukemia patients. Thromb. J. 2023, 21, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naymagon, L.; Mascarenhas, J. Hemorrhage in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Can it be predicted and prevented? Leuk. Res. 2020, 94, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddana, P.S.; Kar, S.S.; Kar, R. Evaluation of the International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis scoring system & its modifications in diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation: A pilot study from southern India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2022, 155, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmarvand, N.; Oak, J.S.; Cascio, M.J.; Alcasid, M.; Goodman, E.; Medeiros, B.C.; Arber, D.A.; Zehnder, J.L.; Ohgami, R.S. A study of disseminated intravascular coagulation in acute leukemia reveals markedly elevated D-dimer levels are a sensitive indicator of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2017, 39, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, B.J.; Estcourt, L. FAB Classification of Leukemia. In Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics, 2nd ed.; Maloy, S., Hughes, K., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.B.; Hoogstraten, B.; Staquet, M.; Winkler, A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 1981, 47, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Di Minno, M.N.; Coppola, A. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in hematologic malignancies. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, M.; Suvajdzic, N.; Elezovic, I.; Bogdanovic, A.; Djordjevic, V.; Miljic, P.; Djunic, I.; Gvozdenov, M.; Colovic, N.; Virijevic, M.; et al. Thrombotic events in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naymagon, L.; Moshier, E.; Tremblay, D.; Mascarenhas, J. Predictors of early hemorrhage in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 2394–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterno, G.; Palmieri, R.; Tesei, C.; Nunzi, A.; Ranucci, G.; Mallegni, F.; Moretti, F.; Meddi, E.; Tiravanti, I.; Marinoni, M.; et al. The ISTH DIC-score predicts early mortality in patients with non-promyelocitic acute myeloid leukemia. Thromb. Res. 2024, 236, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, M.; Suvajdzic, N.; Bogdanovic, A.; Kurtovic, N.K.; Sretenovic, A.; Elezovic, I.; Tomin, D. International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis Scoring System for disseminated intravascular coagulation ≥ 6: A new predictor of hemorrhagic early death in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Med. Oncol. 2013, 30, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantha, S.; Goldman, D.A.; Devlin, S.M.; Lee, J.W.; Zannino, D.; Collins, M.; Douer, D.; Iland, H.J.; Litzow, M.R.; Stein, E.M.; et al. Determinants of fatal bleeding during induction therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia in the ATRA era. Blood 2017, 129, 1763–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnari, C.; Breccia, M.; Di Giuliano, F.; Scalzulli, E.; Divona, M.; Piciocchi, A.; Cicconi, L.; De Bellis, E.; Venditti, A.; Del Principe, M.I.; et al. Early intracranial haemorrhages in acute promyelocytic leukaemia: Analysis of neuroradiological and clinico-biological parameters. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 193, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iba, T.; Helms, J.; Connors, J.M.; Levy, J.H. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gando, S.; Saitoh, D.; Ogura, H.; Mayumi, T.; Koseki, K.; Ikeda, T.; Ishikura, H.; Iba, T.; Ueyama, M.; Eguchi, Y.; et al. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) diagnosed based on the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine criteria is a dependent continuum to overt DIC in patients with sepsis. Thromb. Res. 2009, 123, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, J.; Hambley, B. The Coagulopathy of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: An Updated Review of Pathophysiology, Risk Stratification, and Clinical Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, S.; Döhner, K.; Krauter, J.; Köhne, C.H.; Horst, H.A.; Held, G.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, M.; Wilhelm, S.; Kündgen, A.; Götze, K.; et al. The impact of therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) on outcome in 2853 adult patients with newly diagnosed AML. Blood 2011, 117, 2137–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisada, Y.; Archibald, S.J.; Bansal, K.; Chen, Y.; Dai, C.; Dwarampudi, S.; Balas, N.; Hageman, L.; Key, N.S.; Bhatia, S.; et al. Biomarkers of bleeding and venous thromboembolism in patients with acute leukemia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 1984–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Mustafa, S.; Seier, J.; Tomasits, J.; Haushofer, A. Hematopathological Patterns in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Complications of Overt Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. Diagn. 2025, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Martelli, M.P.; Bolli, N.; Sportoletti, P.; Liso, A.; Tiacci, E.; Haferlach, T. Acute myeloid leukemia with mutated nucleophosmin (NPM1): Is it a distinct entity? Blood 2011, 117, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | |||||||||

| Modifications | Prothrombin Time | D-Dimer | Fibrinogen | Platelet | LDH | INR | Hgb | Genetics | Total Score |

| ISTH Score 1 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | <400 mg/dL = 0 ≥400 mg/dL = 1 | ≥6 | |||

| ISTH Score 2 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | <800 mg/dL = 0 ≥800 mg/dL = 1 | ≥6 | |||

| ISTH Score 3 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | Any positivity = 1 | ≥6 | |||

| ISTH Score 4 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | ≥7 = 0 <7 = 1 | ≥6 | |||

| ISTH Score 5 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | ≤1.2 = 0 >1.2 = 1 | ≥6 | |||

| ISTH Score 6 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | <400 mg/dL = 0 ≥400 mg/dL = 1 | Any positivity = 1 | ≥5 | |||

| ISTH Score 7 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | <800 mg/dL = 0 ≥800 mg/dL = 1 | Any positivity = 1 | ≥5 | |||

| ISTH Score 8 | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | Any positivity = 1 | ≥4 | ||||

| Original Score | <3 = 0 >3 but <6 = 1 >6 = 2 | <500 ng/mL = 0 500–4000 ng/mL = 2 >4000 ng/mL = 3 | >100 mg/dL =0, <100 mg/dL = 1 | >100 × 109/L = 0 <100 × 109/L = 1 <50 × 109/L = 2 | ≥5 overt DIC | ||||

| AML-M3 | Non-M3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 33 (54.1%) | 68 (52.7%) |

| Male | 28 (45.9%) | 61 (47.3%) |

| Age | 45 (18–82) | 49 (18–83) |

| AML Subgroups | M3 61 (32.1%) | M0: 8 (4.2%) |

| M1: 15 (7.9%) | ||

| M2: 45 (23.7%) | ||

| M4: 28 (14.7%) | ||

| M5: 17 (8.9%) | ||

| M6: 4 (2.1%) | ||

| MDS trans. AML: 12 (6.3%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||

| AIDA | 56 (91.8%) | - |

| ATRA + Daunorubicin | 4 (6.6%) | - |

| ATRA + Cytarabine + Daunorubicine | 1 (1.6%) | - |

| 3 + 7 | - | 114 (88.4%) |

| Azacitidine + Venetoclax | - | 7 (5.4%) |

| Azacitidine | - | 4 (3.1%) |

| 2 + 5 | - | 3 (2.3%) |

| ARA-C + Dexamethasone | - | 1 (0.8%) |

| Laboratory Findings, Median (Min-Max) | ||

| WBC (mm3) | 2690 (610–161,600) | 20,930 (600–316,000) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.7 (8.4–11.4) | 8.7 (7.5–9.8) |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 30.6 (19.3–49.8) | 48.2 (29.3–85.5) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 167 (106–275) | 378 (309–483) |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 13.5 (6.0–31.1) | 2.37 (1.13–6.68) |

| DIC with bleeding | 31/61 (50.8%) | 17/129 (13.2%) |

| (# of patients) | ||

| GIS | 29 | 16 |

| CNS | 2 | 0 |

| Alveolar | 0 | 1 |

| Any genetic positivity (excluding t(15;17) *) | 56/190 (29.5%) | |

| 9 | 47 ** | |

| t(8;21) | 1 | 13 |

| t(12;21) | 2 | 5 |

| inv16 | - | 10 |

| FLT3 | 4 | 12 |

| NPM1 | 2 | 13 |

| CEBPA | 0 | 2 |

| Response to induction | 148/190 (77.9%) | |

| Parameter | Median (IQR) | AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3 | PT | 13.80 (12.60–15.15) | 0.639 (0.499–0.779) | 13.45 | 0.742 | 0.567 | 0.149 |

| D-Dimer (mg/L) | 13.50 (5.99–31.13) | 0.510 (0.363–0.658) | 14.60 | 0.419 | 0.467 | 0.785 | |

| PLT (103) | 30.6 (19.3–49.8) | 0.564 (0.415–0.713) | 52.95 | 0.871 | 0.333 | 0.134 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 167.00 (106.00–274.50) | 0.727 (0.600–0.854) | 260.00 | 0.935 | 0.467 | 0.02 | |

| LDH (U/L) | 321.00 (219.75–536.50) | 0.594 (0.450–0.739) | 313.00 | 0.667 | 0.600 | 0.244 | |

| HGB (g/dL) | 9.70 (8.40–11.40) | 0.531 (0.384–0.679) | 8.75 | 0.355 | 0.800 | 0.737 | |

| INR | 1.13 (1.04–1.35) | 0.628 (0.487–0.770) | 1.08 | 0.871 | 0.433 | 0.118 | |

| Non-M3 | PT | 12.90 (12.05–14.00) | 0.553 (0.401–0.705) | 13.55 | 0.529 | 0.643 | 0.552 |

| D-Dimer (mg/L) | 2.37 (1.13–6.68) | 0.572 (0.428–0.716) | 4.85 | 0.471 | 0.688 | 0.822 | |

| PLT (103) | 48.2 (29.3–85.5) | 0.621 (0.484–0.758) | 79.35 | 0.941 | 0.330 | 0.073 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 378.00 (308.50–482.50) | 0.565 (0.413–0.717) | 351.50 | 0.652 | 0.588 | 0.491 | |

| LDH (U/L) | 478.00 (257.00–868.00) | 0.756 (0.634–0.877) | 897 | 0.647 | 0.845 | 0.002 | |

| HGB (g/dL) | 8.70 (7.47–9.75) | 0.517 (0.389–0.644) | 7.47 | 0.118 | 0.732 | 0.758 | |

| INR | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 0.559 (0.426–0.692) | 1.18 | 0.471 | 0.678 | 0.653 |

| Real Test (Bleeding) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||||

| Original ISTH score | Non-M3 | Positive | 13 | 58 | 71 | 76.5 | 48.2 |

| Negative | 4 | 54 | 58 | ||||

| Total | 17 | 112 | 129 | ||||

| M3 | Positive | 29 | 19 | 48 | 93.5 | 36.7 | |

| Negative | 2 | 11 | 13 | ||||

| Total | 31 | 30 | 61 | ||||

| ISTH Score 3 | Non-M3 | Positive | 12 | 38 | 50 | 70.6 | 66.1 |

| Negative | 5 | 74 | 79 | ||||

| Total | 17 | 112 | 129 | ||||

| M3 | Positive | 21 | 10 | 31 | 67.7 | 66.7 | |

| Negative | 10 | 20 | 30 | ||||

| Total | 31 | 30 | 61 | ||||

| ISTH Score 7 | Non-M3 | Positive | 14 | 44 | 58 | 82.4 | 60.7 |

| Negative | 3 | 68 | 71 | ||||

| Total | 17 | 112 | 129 | ||||

| M3 | Positive | 21 | 13 | 34 | 67.7 | 56.7 | |

| Negative | 10 | 17 | 27 | ||||

| Total | 31 | 30 | 61 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orhan, B.; Özkalemkaş, F.; Bayır, T.; Yalçın, C.; Güner, B.; Elgün, E.; Gülderen, E.; Bulur, A.; Ersal, T.; Hunutlu, F.Ç.; et al. Predicting Bleeding in AML-Associated DIC: Limitations of the ISTH Score and a Modified Approach. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3053. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233053

Orhan B, Özkalemkaş F, Bayır T, Yalçın C, Güner B, Elgün E, Gülderen E, Bulur A, Ersal T, Hunutlu FÇ, et al. Predicting Bleeding in AML-Associated DIC: Limitations of the ISTH Score and a Modified Approach. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3053. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233053

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrhan, Bedrettin, Fahir Özkalemkaş, Tuba Bayır, Cumali Yalçın, Büşra Güner, Ezel Elgün, Esra Gülderen, Ayşe Bulur, Tuba Ersal, Fazıl Çağrı Hunutlu, and et al. 2025. "Predicting Bleeding in AML-Associated DIC: Limitations of the ISTH Score and a Modified Approach" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3053. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233053

APA StyleOrhan, B., Özkalemkaş, F., Bayır, T., Yalçın, C., Güner, B., Elgün, E., Gülderen, E., Bulur, A., Ersal, T., Hunutlu, F. Ç., Koca, T. G., Çubukçu, S., Yavuz, Ş., & Özkocaman, V. (2025). Predicting Bleeding in AML-Associated DIC: Limitations of the ISTH Score and a Modified Approach. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3053. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233053