Recessive SMC5 Variants in a Family with Near-Tetraploidy/Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Cytogenetic Analysis

2.3. Exome Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.4. Variant Confirmation and Interpretation

2.5. Evolutionary Conservation Analysis & Protein Structure Prediction

3. Results

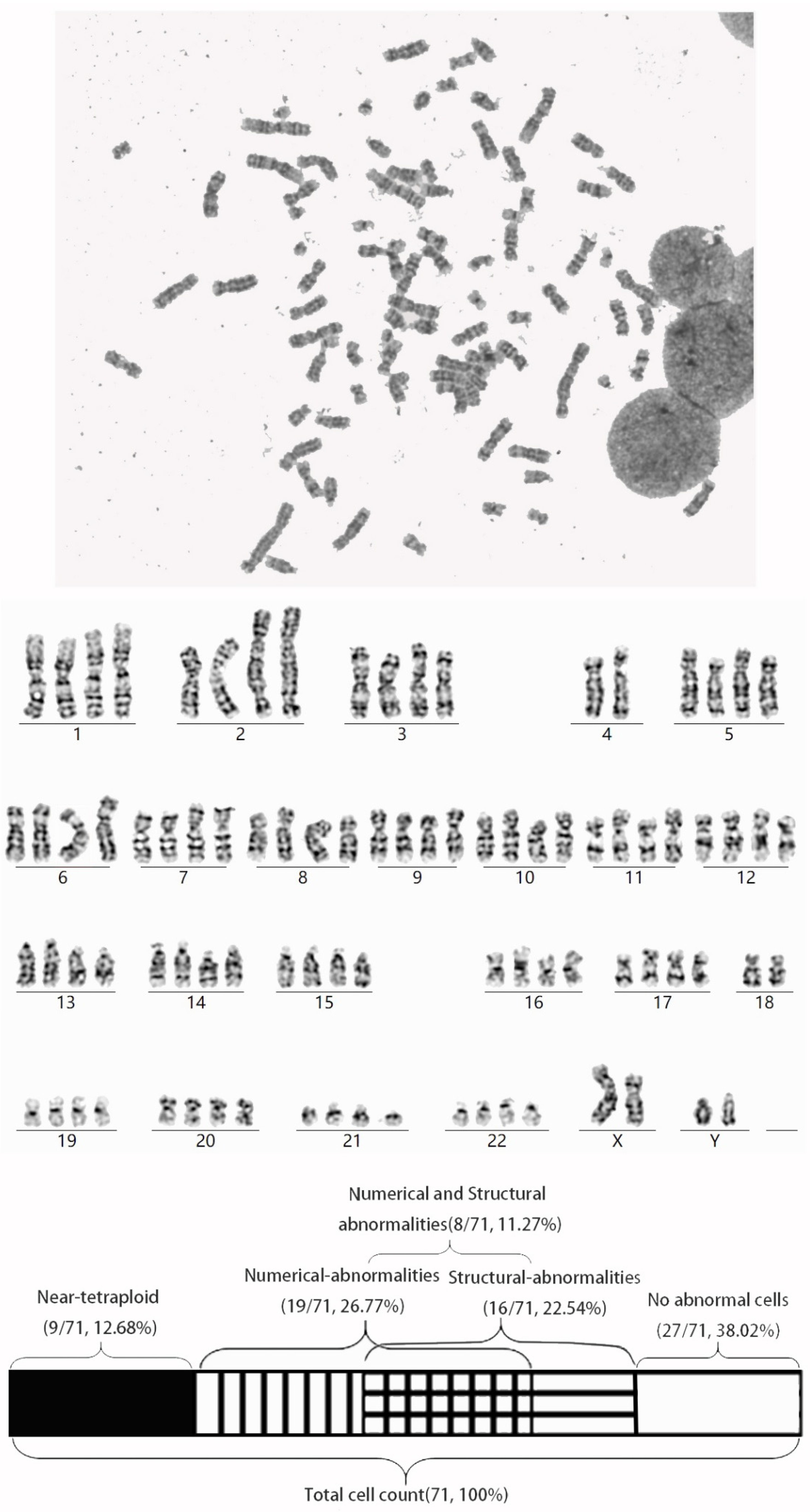

3.1. Clinical Presentation and Initial Karyotype Analysis Revealing Near-Tetraploidy/MVA

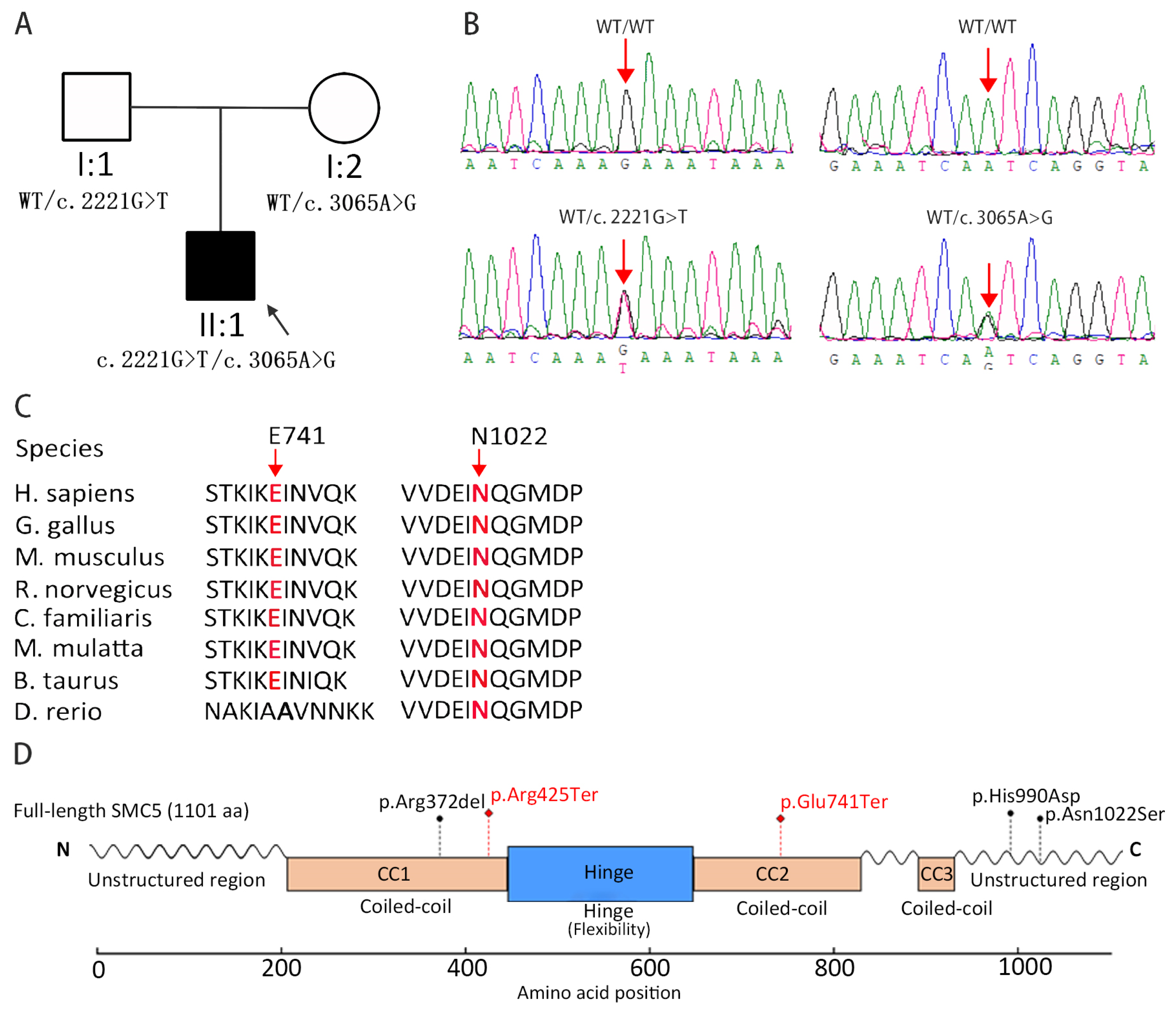

3.2. Identification of SMC5 Variants

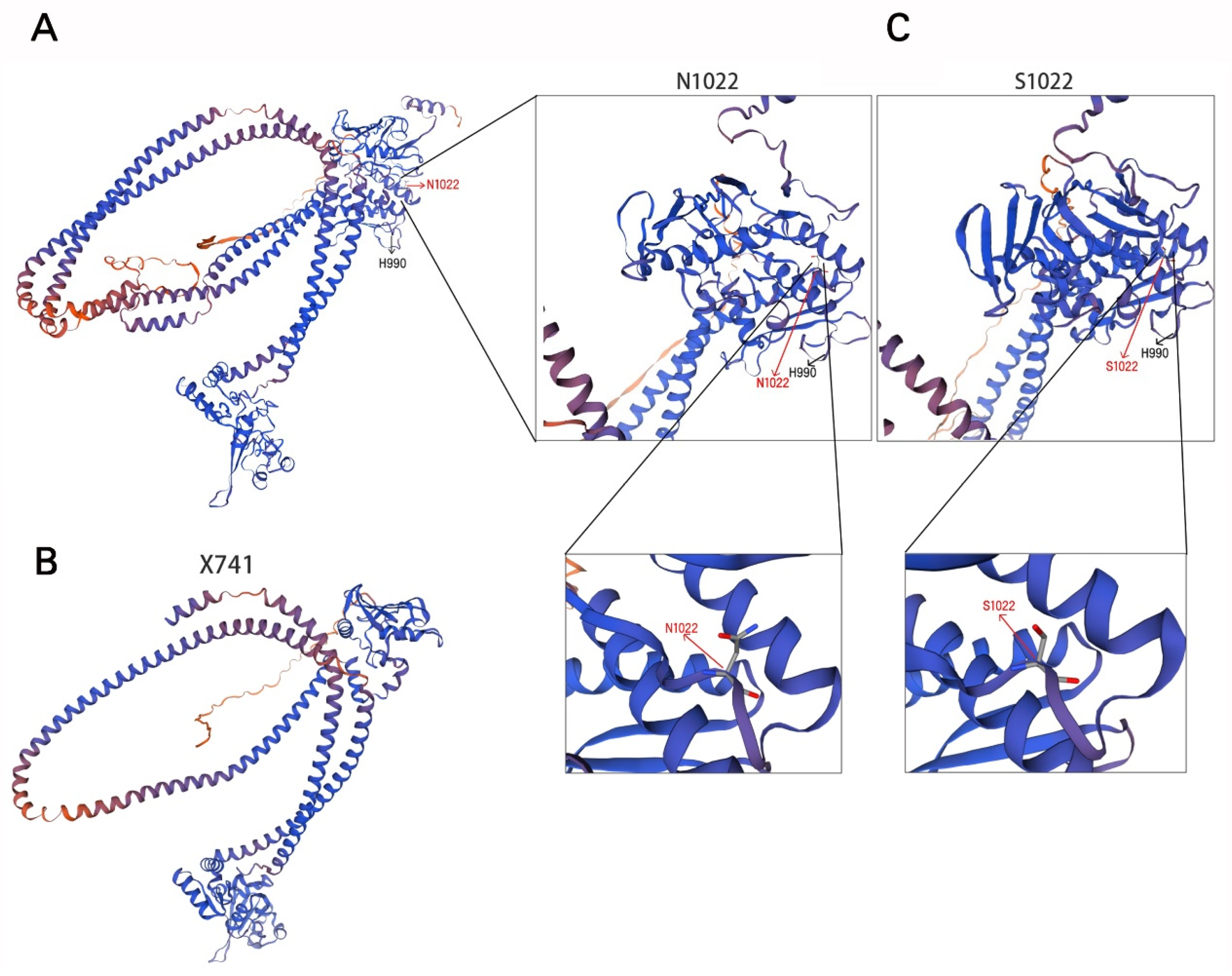

3.3. Evolutionary Conservation and Protein Structural Analysis

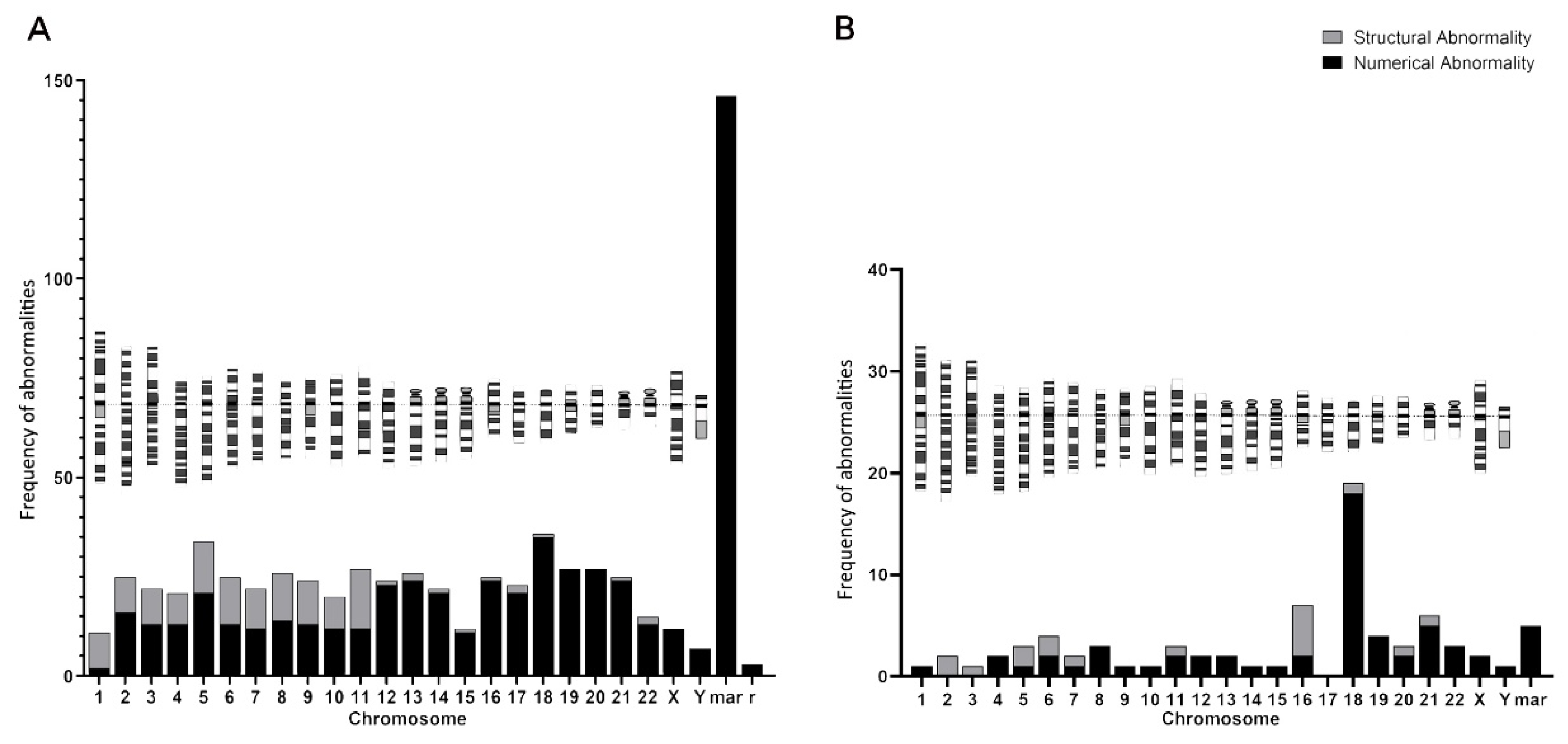

3.4. Further Analysis of Chromosomal Karyotyping

3.5. Chromosomes with Unusual Structural Abnormalities

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kajii, T.; Ikeuchi, T.; Yang, Z.-Q.; Nakamura, Y.; Tsuji, Y.; Yokomori, K.; Kawamura, M.; Fukuda, S.; Horita, S.; Asamoto, A. Cancer-prone syndrome of mosaic variegated aneuploidy and total premature chromatid separation: Report of five infants. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 104, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemont, S.; Bocéno, M.; Rival, J.M.; Méchinaud, F.; David, A. High risk of malignancy in mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 109, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.; Anyane-Yeboa, K.; Taterka, P.; Yu, C.Y.; Olsen, D. Mosaic variegated aneuploidy with microcephaly: A new human mitotic mutant? Ann. Genet. 1991, 34, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, S.; Coleman, K.; Reid, S.; Plaja, A.; Firth, H.; FitzPatrick, D.; Kidd, A.; Méhes, K.; Nash, R.; Robin, N.; et al. Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition caused by biallelic mutations in BUB1B. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1159–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Voer, R.M.; van Kessel, A.G.; Weren, R.D.A.; Ligtenberg, M.J.L.; Smeets, D.; Fu, L.; Vreede, L.; Kamping, E.J.; Verwiel, E.T.P.; Hahn, M.-M.; et al. Germline mutations in the spindle assembly checkpoint genes BUB1 and BUB3 are risk factors for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya-Beltri, C.; Osorio, A.; Torres-Ruiz, R.; Gómez-Sánchez, D.; Trakala, M.; Sánchez-Belmonte, A.; Mercadillo, F.; Hurtado, B.; Pitarch, B.; Hernández-Núñez, A.; et al. Biallelic germline mutations in MAD1L1 induce a syndrome of aneuploidy with high tumor susceptibility. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabd5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Salam, G.M.H.; Hellmuth, S.; Gradhand, E.; Käseberg, S.; Winter, J.; Pabst, A.-S.; Eid, M.M.; Thiele, H.; Nürnberg, P.; Budde, B.S.; et al. Biallelic MAD2L1BP (p31comet) mutation is associated with mosaic aneuploidy and juvenile granulosa cell tumors. JCI Insight 2023, 5, e170079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, S.; de Wolf, B.; Hanks, S.; Zachariou, A.; Marcozzi, C.; Clarke, M.; de Voer, R.M.; Etemad, B.; Uijttewaal, E.; Ramsay, E.; et al. Biallelic TRIP13 mutations predispose to Wilms tumor and chromosome missegregation. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1148–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolf, E.; Oghabian, A.; Akinyi, M.V.; Hanks, S.; Tromer, E.C.; van Hooff, J.J.E.; van Voorthuijsen, L.; van Rooijen, L.E.; Verbeeren, J.; Uijttewaal, E.C.H.; et al. Chromosomal instability by mutations in the novel minor spliceosome component CENATAC. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, K.; Hanks, S.; Ruark, E.; Barros-Núñez, P.; Elliott, A.; Murray, A.; Lane, A.H.; Shannon, N.; Callier, P.; Chitayat, D.; et al. Mutations in CEP57 cause mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, W.-B.; Dai, L.; Tian, F.; Luo, Z.; Shen, F.; Tu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tan, C.; et al. Mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome with tetraploidy and predisposition to male infertility triggered by mutant CEP192. HGG Adv. 2024, 5, 100256. [Google Scholar]

- Grange, L.J.; Reynolds, J.J.; Ullah, F.; Isidor, B.; Shearer, R.F.; Latypova, X.; Baxley, R.M.; Oliver, A.W.; Ganesh, A.; Cooke, S.L.; et al. Pathogenic variants in SLF2 and SMC5 cause segmented chromosomes and mosaic variegated hyperploidy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M.; Villarroya-Beltri, C. Mosaic variegated aneuploidy in development, ageing and cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. Condensin-based chromosome organization from bacteria to vertebrates. Cell 2016, 164, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, F. SMC complexes: From DNA to chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatskevich, S.; Rhodes, J.; Nasmyth, K. Organization of chromosomal DNA by SMC complexes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2019, 53, 445–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Piccoli, G.; Cortes-Ledesma, F.; Ira, G.; Torres-Rosell, J.; Uhle, S.; Farmer, S.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Machin, F.; Ceschia, A.; McAleenan, A.; et al. Smc5-Smc6 mediate DNA double-strand-break repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1032–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, P.R.; Porteus, M.H.; Yu, H. Human SMC5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3377–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Blobel, G. A SUMO ligase is part of a nuclear multiprotein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4777–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palecek, J.J.; Gruber, S. Kite proteins: A superfamily of SMC/kleisin partners. Structure 2015, 23, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, E.A.; Palecek, J.; Sergeant, J.; Taylor, E.; Lehmann, A.R.; Watts, F.Z. Nse2, a component of the Smc5-6 complex, is a SUMO ligase. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesar, P.; Stejskal, K.; Potesil, D.; Murray, J.M.; Palecek, J.J. Role of Nse1 subunit as a ubiquitin ligase. Cells 2022, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasmyth, K.; Haering, C.H. Cohesin: Its roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 525–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T. Condensins: Universal organizers of chromosomes with diverse functions. Genes. Dev. 2012, 26, 1659–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G. Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbert, M.T.; Wadsworth, M.E.; Staley, L.A.; Hoyt, K.L.; Pickett, B.; Miller, J.; Duce, J.; Kauwe, J.S.K.; Ridge, P.G. Evaluating the necessity of PCR duplicate removal from next-generation sequencing data and a comparison of approaches. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A.; del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Tu, M.; Zhao, L.; Mei, H.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, Y. SMAD6 is frequently mutated in nonsyndromic radioulnar synostosis. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 2577–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Arenz, J.; Rangi, G.K.; Zhao, X.; Ye, H. Architecture of the Smc5/6 complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a unique interaction between the Nse5-6 subcomplex and the hinge regions of Smc5 and Smc6. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 8507–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.P.; Zhao, X. The multi-functional Smc5/6 complex in genome protection and disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023, 30, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Haluska, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Jin, D.; Cheng, T.; Wang, H.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of Smc5/6 in multiple states reveal its assembly and functional mechanisms. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räschle, M.; Smeenk, G.; Hansen, R.K.; Temu, T.; Oka, Y.; Hein, M.Y.; Nagaraj, N.; Long, D.T.; Walter, J.C.; Hofmann, K.; et al. Proteomics reveals dynamic assembly of repair complexes during bypass of DNA cross-links. Science 2015, 348, 1253671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwertman, P.; Bekker-Jensen, S.; Mailand, N. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Feature | P7 [12] | P8 [12] | P9-1 [12] | P9-2 [12] | Present Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics & Genetics | |||||

| Origin | Spain | US | US | US | China |

| SMC5 Variants | c.1110_1112del; p.(Arg372del)/ | c.2970C>G; p.(His990Asp)/Homozygous | c.2970C>G; p.(His990Asp)/Homozygous | c.2970C>G; p.(His990Asp)/Homozygous | c.2221G>T; p.(Glu741Ter)/ |

| c.1273C>T; p.(Arg425Ter) | c.3065A>G; p.(Asn1022Ser) | ||||

| Growth & Development | |||||

| Prenatal/Birth Parameters | Severe IUGR | IUGR, SGA | IUGR | IUGR, Premature | Within normal limits |

| (−4.25 SD) | (−1.45 SD) | (−2.87 SD) | (−1.56 SD) | ||

| Postnatal Short Stature | + (Severe, −5.68 SD) | + (−2.94 SD) | + (−5.87 SD) | + (−4.65 SD) | - (Mild delay, normalized by age 4) |

| Microcephaly | + (Severe, −7.67 SD) | + (−4.65 SD) | + (−4.88 SD) | + (−6.93 SD) | - |

| Neurological & Development | |||||

| Global Developmental Delay/Intellectual Disability | + (Learning difficulties) | - (Motor delay due to blindness) | - | - (Mild resolved motor delay) | + (Mild, resolved) |

| Seizures | Not reported | + | Not reported | Not reported | - |

| Behavioral Anomalies (e.g., Anxiety) | Not reported | + | + | + | - |

| Craniofacial Features | |||||

| Dysmorphic Facies | + (Long face, beaked nose, epicanthal folds) | + (Triangular face, frontal bossing, micrognathia) | + (Triangular face, frontal bossing) | + (Triangular face, micrognathia, downslanting palpebral fissures) | Absent |

| Systemic Involvement | |||||

| Cardiac Abnormalities | + (PDA, Pulmonary stenosis) | + (Innocent murmur) | + (Innocent murmur) | + (Mild pulmonary stenosis, PFO/ASD) | - |

| Ocular Abnormalities | Not reported | + (Microphthalmia, cataracts, retinal detachment) | Not reported | + (Persistent fetal vasculature) | - |

| Hematological/Immunological Abnormalities | Not assessed | + (Lymphopenia, eosinophilia) | + (Thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia) | + (Anemia, neutropenia, MDS) | - |

| Skeletal Anomalies | + (High palate) | - | + (Clinodactyly, pes planus) | + (Clinodactyly, brachydactyly, kyphosis) | - |

| Endocrine Anomalies | + (Hyperinsulinism) | + (Elevated TSH) | + (Elevated TSH) | + (Elevated TSH, premature adrenarche) | - |

| Other | Hypospadias | Sacral dimple, elevated LFTs | Sacral dimple, elevated LFTs | Sacral dimple, pilonidal cyst, elevated LFTs | Hypospadias |

| Laboratory & Cytogenetic Findings | |||||

| Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy (MVA) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Near-Tetraploidy | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | + |

| Summary: Features Absent in Present Patient * | - | - | - | - | 10/13 (76.9%) |

| Item | Variant 1 | Variant 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coordinate (GRCh37) | chr9: 72938469 | chr9: 72965205 |

| Transcript | NM_015110.3 | NM_015110.3 |

| cDNA Change | c.2221G>T | c.3065A>G |

| Protein Change | p.(Glu741Ter) | p.(Asn1022Ser) |

| Variant Type | Missense | Missense |

| Zygosity | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| Variant Allele Fraction (VAF) | 48% | 53% |

| Population Frequency (gnomAD) a | Not found | 0.000006821 |

| In Silico Prediction | CADD: 39 (Damaging) | CADD: 27.1 (Damaging) |

| SIFT: - | SIFT: Deleterious | |

| PolyPhen-2: - | PolyPhen-2: 1 | |

| ACMG/AMP Classification | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP4) | Likely Pathogenic (PM2, PP3, PP4, PM3) |

| Origin | Paternal | Maternal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Tu, M.; Zhao, L.; Shen, F.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S. Recessive SMC5 Variants in a Family with Near-Tetraploidy/Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233022

Yang Y, Li N, Liu C, Li S, Tu M, Zhao L, Shen F, Zheng Y, Wang H, Zhao S. Recessive SMC5 Variants in a Family with Near-Tetraploidy/Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233022

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yongjia, Nian Li, Cheng Liu, Songting Li, Ming Tu, Liu Zhao, Fang Shen, Yu Zheng, Hua Wang, and Sha Zhao. 2025. "Recessive SMC5 Variants in a Family with Near-Tetraploidy/Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233022

APA StyleYang, Y., Li, N., Liu, C., Li, S., Tu, M., Zhao, L., Shen, F., Zheng, Y., Wang, H., & Zhao, S. (2025). Recessive SMC5 Variants in a Family with Near-Tetraploidy/Mosaic Variegated Aneuploidy. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233022