Clinical Significance of Incidentally Detected Parotid Masses on Brain MRI and PET-CT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

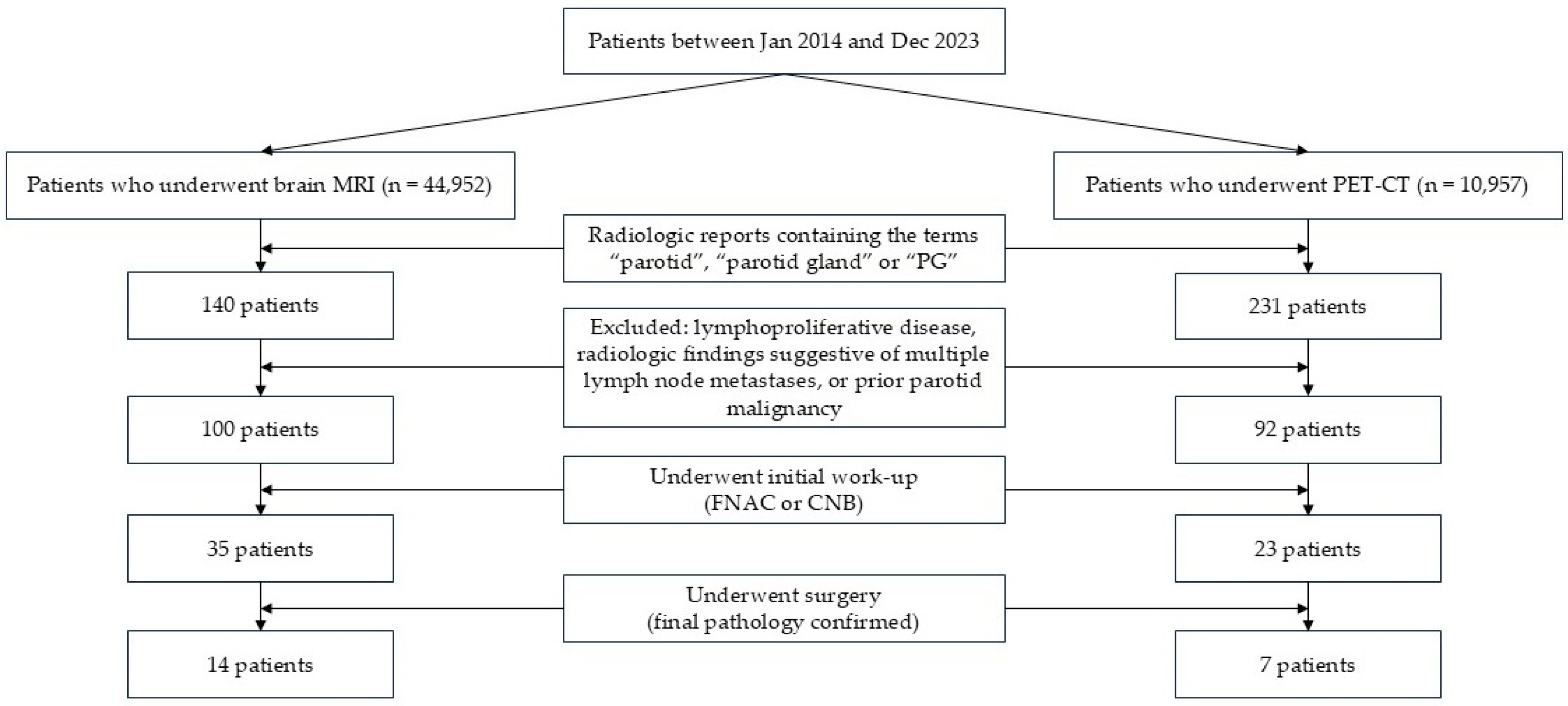

2.1. Patients

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Incidence of Parotid Incidentalomas on Brain MRI and PET-CT

3.2. Characteristics of Patients with Parotid Incidentalomas Who Underwent Further Evaluation

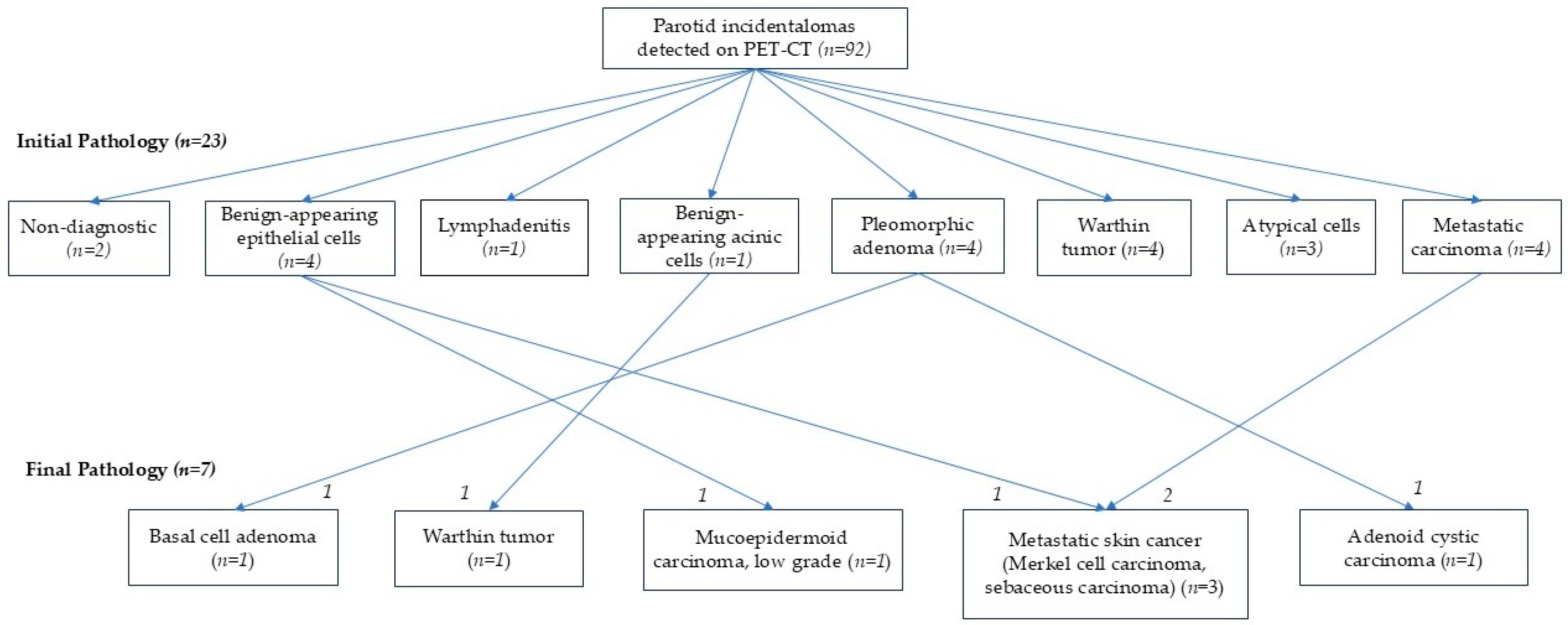

3.3. Comparison Between Initial Work-Up and Final Pathologic Results

3.4. Clinical Outcomes During Follow-Up of Parotid Incidentalomas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mashrah, M.A.; Al-Sharani, H.M.; Al-Aroomi, M.A.; Abdelrehem, A.; Aldhohrah, T.; Wang, L. Surgical interventions for management of benign parotid tumors: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3631–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maahs, G.S.; Oppermann Pde, O.; Maahs, L.G.; Machado Filho, G.; Ronchi, A.D. Parotid gland tumors: A retrospective study of 154 patients. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinheimer, A.; Vieira, D.S.; Cordeiro, M.M.; Rivero, E.R. Retrospective study of 124 cases of salivary gland tumors and literature review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e1025–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, S.; Therkildsen, M.H.; Bjørndal, K.; Homøe, P. Pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland 1985–2010: A Danish nationwide study of incidence, recurrence rate, and malignant transformation. Head Neck 2016, 38 (Suppl. S1), E1364–E1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnepp, D.R. Malignant mixed tumors of the salivary glands: A review. Pathol. Ann. 1993, 28, 279–328. [Google Scholar]

- Colella, G.; Cannavale, R.; Flamminio, F.; Foschini, M.P. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: A systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Jethwa, A.R.; Khariwala, S.S.; Johnson, J.; Shin, J.J. Sensitivity, specificity, and posttest probability of parotid fine-needle aspiration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.H.; Volk, E.E.; Wilbur, D.C.; Cytopathology Resource Committee; College of American Pathologists. Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology: Lessons from the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Nongynecologic Cytology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2005, 129, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, C.C.; Pai, R.K.; Schneider, F.; Duvvuri, U.; Ferris, R.L.; Johnson, J.T.; Seethala, R.R. Salivary gland tumor fine needle aspiration cytology: A proposal for a risk stratification classification. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 143, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makis, W.; Ciarallo, A.; Gotra, A. Clinical significance of parotid gland incidentalomas on (18)F-FDG PET/CT. Clin. Imaging 2015, 39, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.C.; Zuo, C.T.; Hua, F.C.; Huang, Z.M.; Tan, H.B.; Zhao, J.; Guan, Y.H. Efficacy of conventional whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT in the incidental findings of parotid masses. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2010, 24, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Nolli, T.; Bannister, M. Parotid incidentalomas: A systematic review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2021, 135, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasen, M.H.; Hutz, M.J.; Yuhan, B.T.; Britt, C.J. Deep Lobe Parotid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 166, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, F.; Latif, M.F.; Farooq, A.; Tirmazy, S.H.; AlShahrani, S.; Bashir, S.; Bukhari, N. Performance Status Assessment by Using ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) Score for Cancer Patients by Oncology Healthcare Professionals. Case Rep. Oncol. 2019, 12, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, P.H.; Campbell, R.C.; Irwin, M.G.; American Society of Anesthesiologists. The ASA Physical Status Classification: Inter-observer consistency. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2002, 30, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.L.; Yoon, D.Y.; Baek, S.; Lim, K.J.; Yun, E.J.; Cho, Y.K.; Bae, W.J.; Chung, E.J.; Kwon, K.H. Incidental focal FDG uptake in the parotid glands on PET/CT in patients with head and neck malignancy. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, R.R.; Pawaroo, D.; Beadsmoore, C.; Hujairi, N.; Newman, D. Parotid incidentalomas on positron emission tomography: What is their clinical significance? Nucl. Med. Commun. 2019, 40, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T.; Kawabe, J.; Koyama, K.; Ochi, H.; Yamada, R.; Sakamoto, H.; Matsuda, M.; Ohashi, Y.; Nakai, Y. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of parotid mass lesions. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998, 118, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Rassekh, C.H.; Cost, J.L.; Hogg, J.P.; Hurst, M.K.; Marano, G.D.; Ducatman, B.S. Positron emission tomography in Warthin’s tumor mimicking malignancy impacts the evaluation of head and neck patients. Am. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Med. Surg. 2015, 36, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado, A.; León, X.; Llansana, A.; Valero, C.; Casasayas, M.; Fernandez-León, A.; Quer, M. Warthin’s tumour as a parotid gland incidentaloma identified by PET-CT scan in a large series of cases. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 76, 3046–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, I.C.; Baek, H.J.; Ryu, K.H.; Moon, J.I.; Cho, E.; An, H.J.; Yoon, S.; Baik, J. Prevalence and Clinical Implications of Incidentally Detected Parotid Lesions as Blind Spot on Brain MRI: A Single-Center Experience. Medicina 2021, 57, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielker, J.; Grosheva, M.; Ihrler, S.; Wittig, A.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Contemporary Management of Benign and Malignant Parotid Tumors. Front. Surg. 2018, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Ismaila, N.; Beadle, B.; Caudell, J.J.; Chau, N.; Deschler, D.; Glastonbury, C.; Kaufman, M.; Lamarre, E.; Lau, H.Y.; et al. Management of Salivary Gland Malignancy: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1909–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethala, R.R.; Stenman, G. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: Tumors of the Salivary Gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2017, 11, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faquin, W.C.; Rossi, E.D.; Baloch, Z.; Barkan, G.A.; Foschini, M.P.; Kurtycz, D.F.I.; Pusztaszeri, M.P.; Vielh, P. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. In The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, E.D.; Faquin, W.C. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC): An international effort toward improved patient care—When the roots might be inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018, 126, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurry, K.J.; Karunaratne, D.; Westley, S.; Booth, A.; Ramesar, K.C.R.B.; Zhang, T.T.; Williams, M.; Howlett, D.C. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy in the diagnosis of parotid neoplasia: An overview and update with a review of the literature. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20210972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnin, T.; Kawata, R.; Higashino, M.; Nishikawa, S.; Terada, T.; Haginomori, S.-I. Patterns of lymph node metastasis and the management of neck dissection for parotid carcinomas: A single-institute experience. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 24, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, A.; Borowczak, J.; Choussy, O.; Lesnik, M.; Badois, N.; Klijanienko, J. Comparative analysis of the World Health Organization Reporting System for head and neck cytopathology and the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2025, 133, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, P.P.M.; Gupta, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Metastatic tumours to the parotid: A 20-year single institutional experience with an emphasis on 14 unusual presentations. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2024, 73, 152386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Brain MRI | PET-CT |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 100/44,952 (0.22%) | 92/10,957 (0.84%) |

| Sex (Male:Female) | 47:53 | 68:24 |

| Age (years) | 68.90 ± 12.61 | 69.49 ± 11.64 |

| Initial pathologic evaluation (FNAC 1 or CNB 2) | 35/100 (35.0%) | 23/92 (25.0%) |

| Indication | Cases (n) | Stage I−II | Stage III−IV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric cancer | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Lung cancer | 28 | 8 | 20 |

| Sarcoma | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hepato-biliary cancer | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Breast cancer | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Colorectal cancer | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Primary malignancy of unknown origin | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Esophageal cancer | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Head and Neck cancer | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Ovary/Cervix cancer | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Skin cancer | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Pancreas cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Prostate cancer | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Thyroid cancer | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 | ||

| Screening of health | 1 | ||

| Total | 92 | 47 | 45 |

| Characteristics | Further Evaluation | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performed (n = 35) | Not Performed (n = 65) | |||||

| Sex (Male:Female) | 15:20 | 32:33 | 0.675 | |||

| Age (years) | 69.20 ± 10.23 | 68.74 ± 13.80 | 0.182 | |||

| Size (cm) | 1.87 ± 0.61 | 1.83 ± 0.99 | 0.067 | |||

| ECOG (0–1:2–4) | 27:8 | 48:17 | 0.811 | |||

| ASA (1–2:3–4) | 12:23 | 27:38 | 0.312 | |||

| Indication | Cancer work-up Brain tumor Dementia Stroke Trauma/Hemorrhage Aneurysm Neuropathy Dizziness Infection/inflammation Seizure Headache | 2 2 4 14 2 2 7 2 0 0 0 | Cancer work-up Brain tumor Dementia Stroke Trauma/Hemorrhage Aneurysm Neuropathy Dizziness Infection/inflammation Seizure Headache | 9 2 4 23 2 1 4 8 3 5 4 | ||

| Characteristics | Further Evaluation | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performed (n = 23) | Not Performed (n = 69) | ||||

| Sex (Male:Female) | 16:7 | 51:18 | 0.331 | ||

| Age (years) | 68.70 ± 13.29 | 69.52 ± 11.31 | 0.772 | ||

| SUV | 7.02 ± 2.97 | 6.77 ± 2.73 | 0.859 | ||

| Stage (I–II:III–IV) | 17:6 | 30:39 | 0.016 | ||

| Primary site | Colorectal Esophageal Hepatobiliary Head and Neck Lung Ovary/Cervix Sarcoma Skin Thyroid | 3 2 1 8 3 1 1 3 2 | Breast Colorectal MUO Esophageal Gastric Hepatobiliary Head and Neck Lung Ovary/Cervix Pancreas Prostate Skin Thyroid | 1 8 3 1 5 5 3 25 4 1 4 3 4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.S.; Jang, J.I.; Wee, J.H.; Kang, J.W.; Kang, H.S.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, H. Clinical Significance of Incidentally Detected Parotid Masses on Brain MRI and PET-CT. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222895

Lee JS, Jang JI, Wee JH, Kang JW, Kang HS, Kwon MJ, Kim H. Clinical Significance of Incidentally Detected Parotid Masses on Brain MRI and PET-CT. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222895

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Joong Seob, Jeong In Jang, Jee Hye Wee, Jeong Wook Kang, Ho Suk Kang, Mi Jung Kwon, and Heejin Kim. 2025. "Clinical Significance of Incidentally Detected Parotid Masses on Brain MRI and PET-CT" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222895

APA StyleLee, J. S., Jang, J. I., Wee, J. H., Kang, J. W., Kang, H. S., Kwon, M. J., & Kim, H. (2025). Clinical Significance of Incidentally Detected Parotid Masses on Brain MRI and PET-CT. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222895