Hybrid State–Space and Vision Transformer Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification in Prenatal Diagnostics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We introduce a hybrid state–space and vision transformer (SSM-ViT) architecture that unifies sequential and spatial feature modeling for robust fetal ultrasound plane classification.

- We propose a gated and residual fusion mechanism that adaptively balances local continuity captured by the SSM and global semantics extracted by the ViT, supported by detailed ablation and sensitivity analyses.

- We integrate a temperature-scaled confidence calibration module to improve predictive reliability, achieving consistent performance across three independent datasets without retraining.

- We provide a comprehensive empirical evaluation on Fetal_Planes_DB, Fetal Head (Large), and HC18, demonstrating superior accuracy, calibration, and cross-domain generalization compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

2. Related Work

3. Hybrid Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification

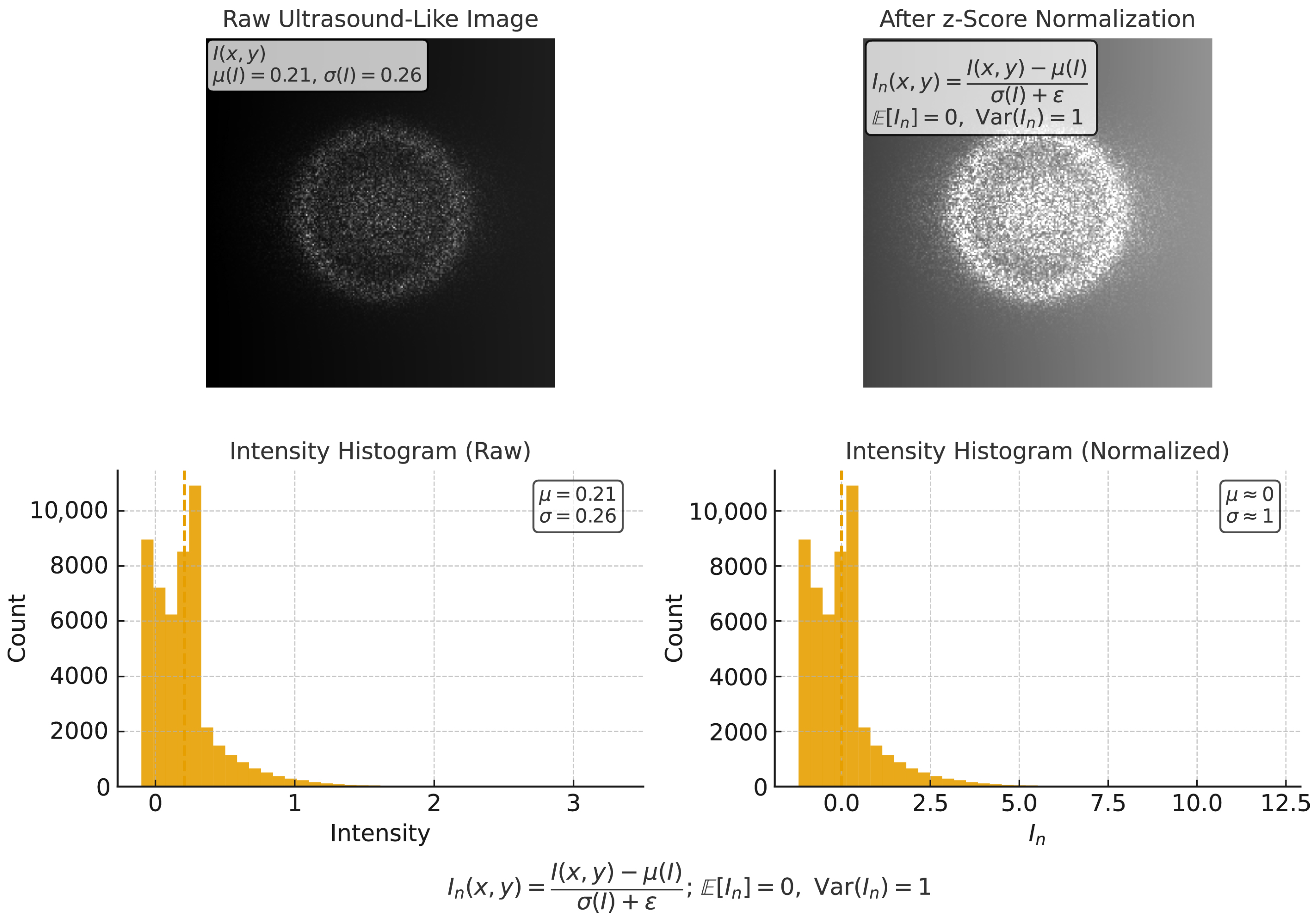

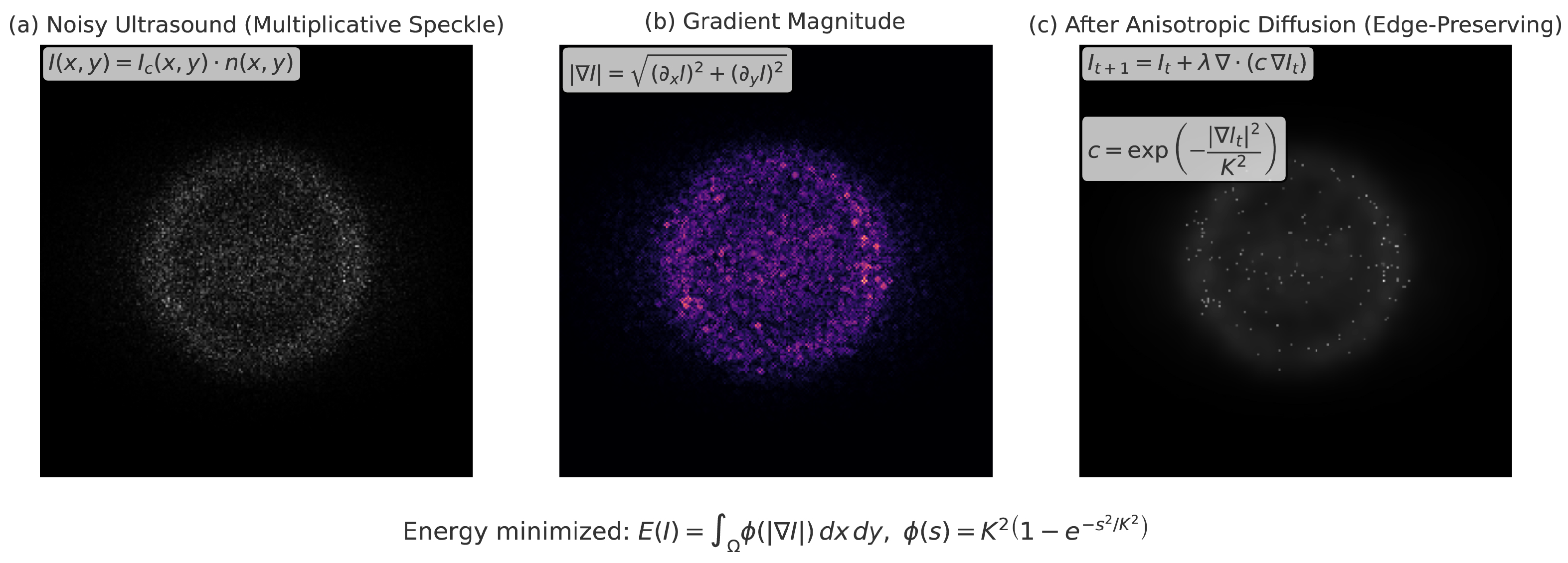

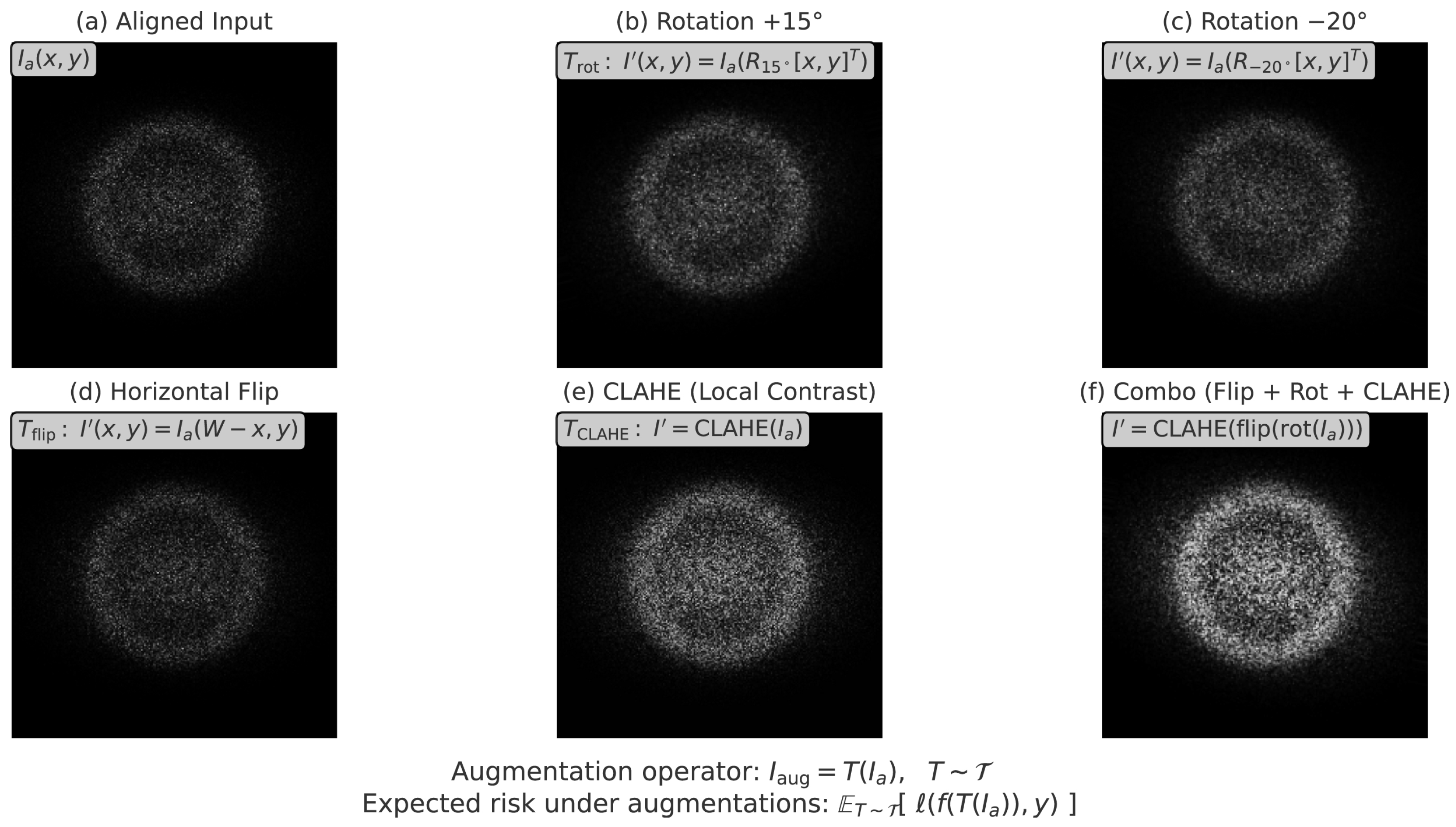

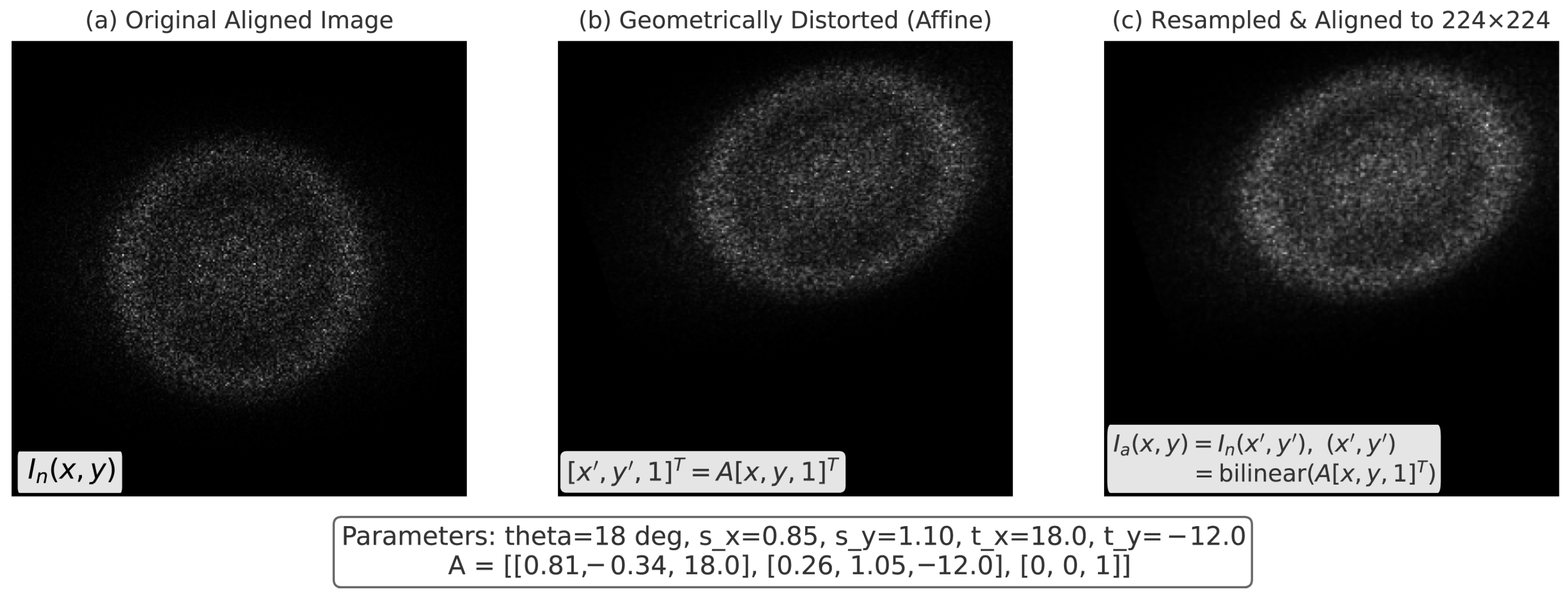

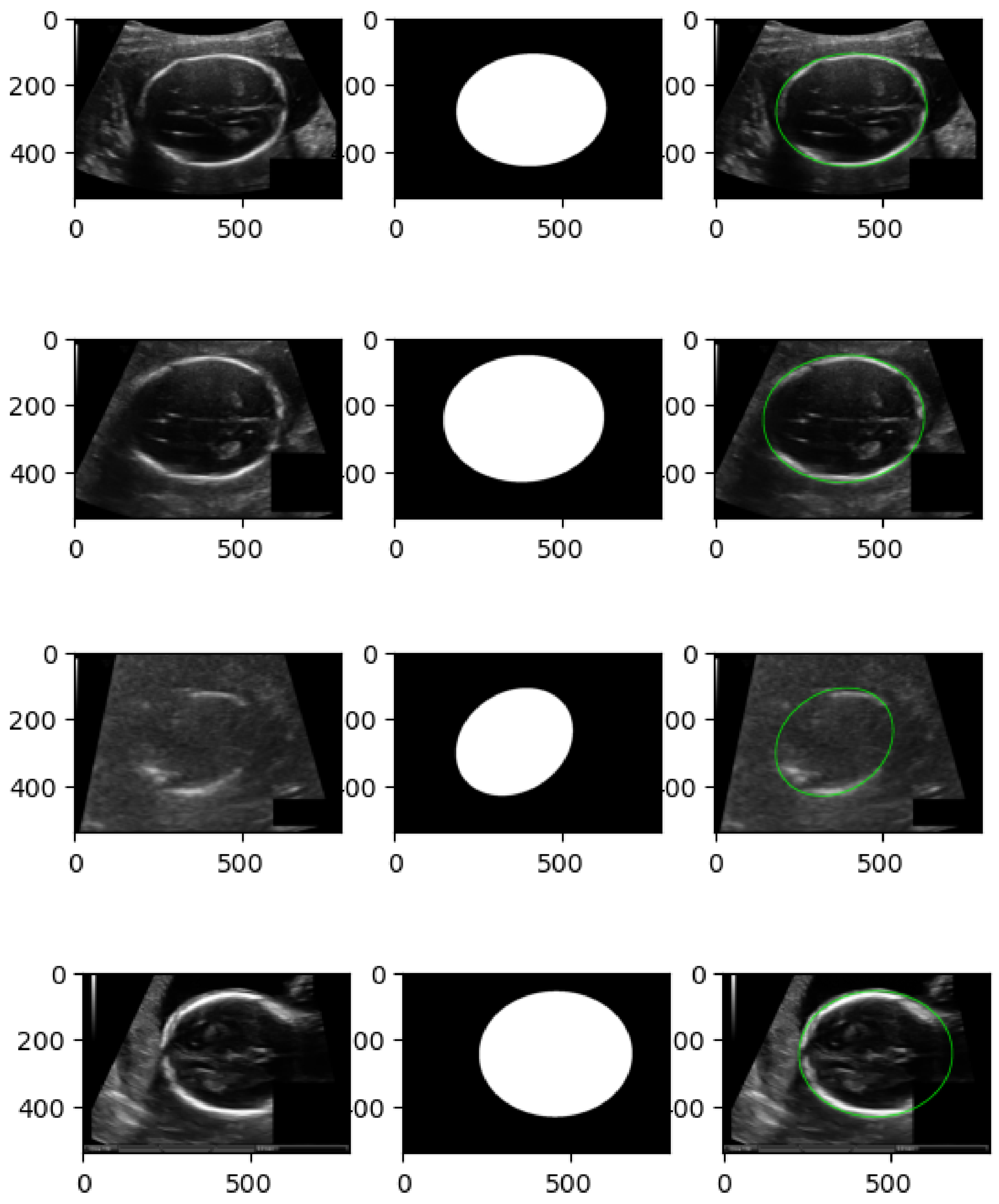

3.1. Image Preprocessing for Ultrasound Harmonization

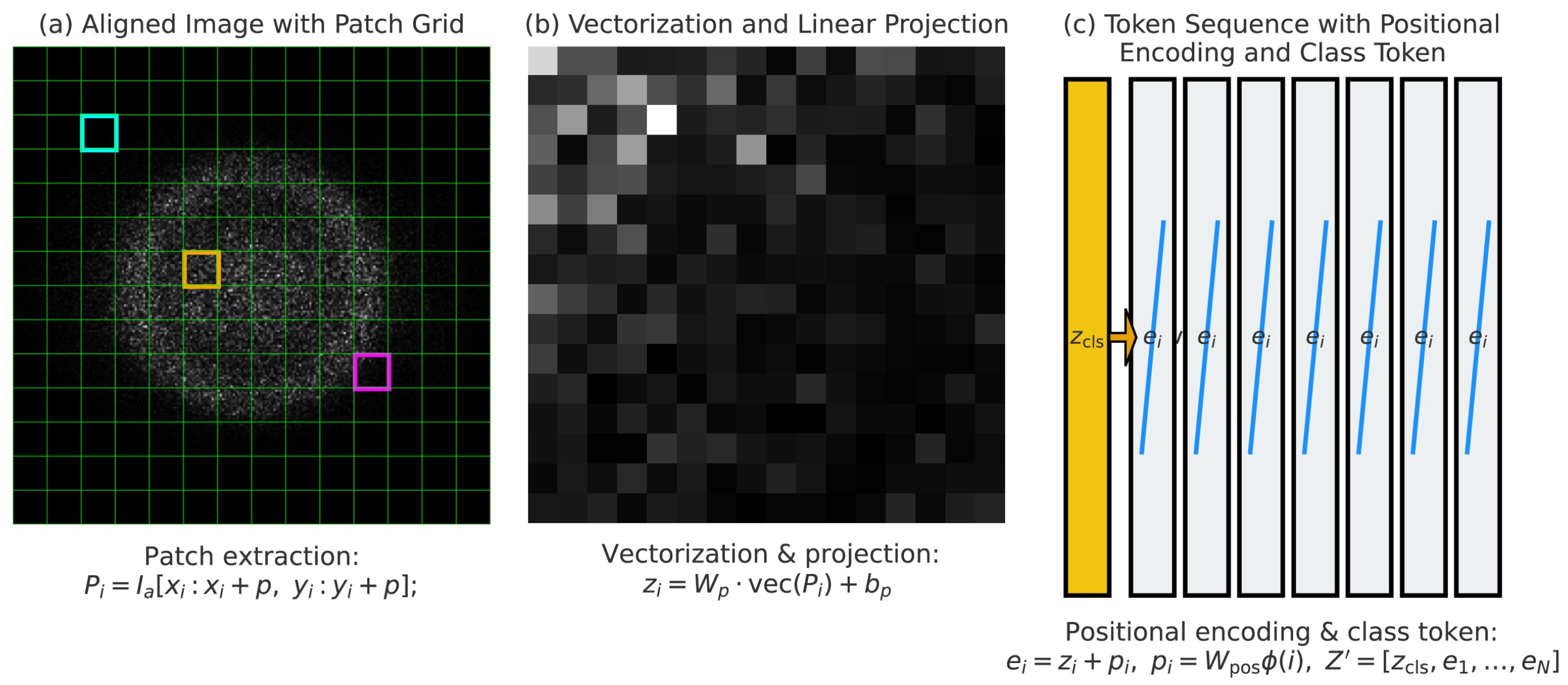

3.2. Patch Embedding and Tokenization for Sequential Representation

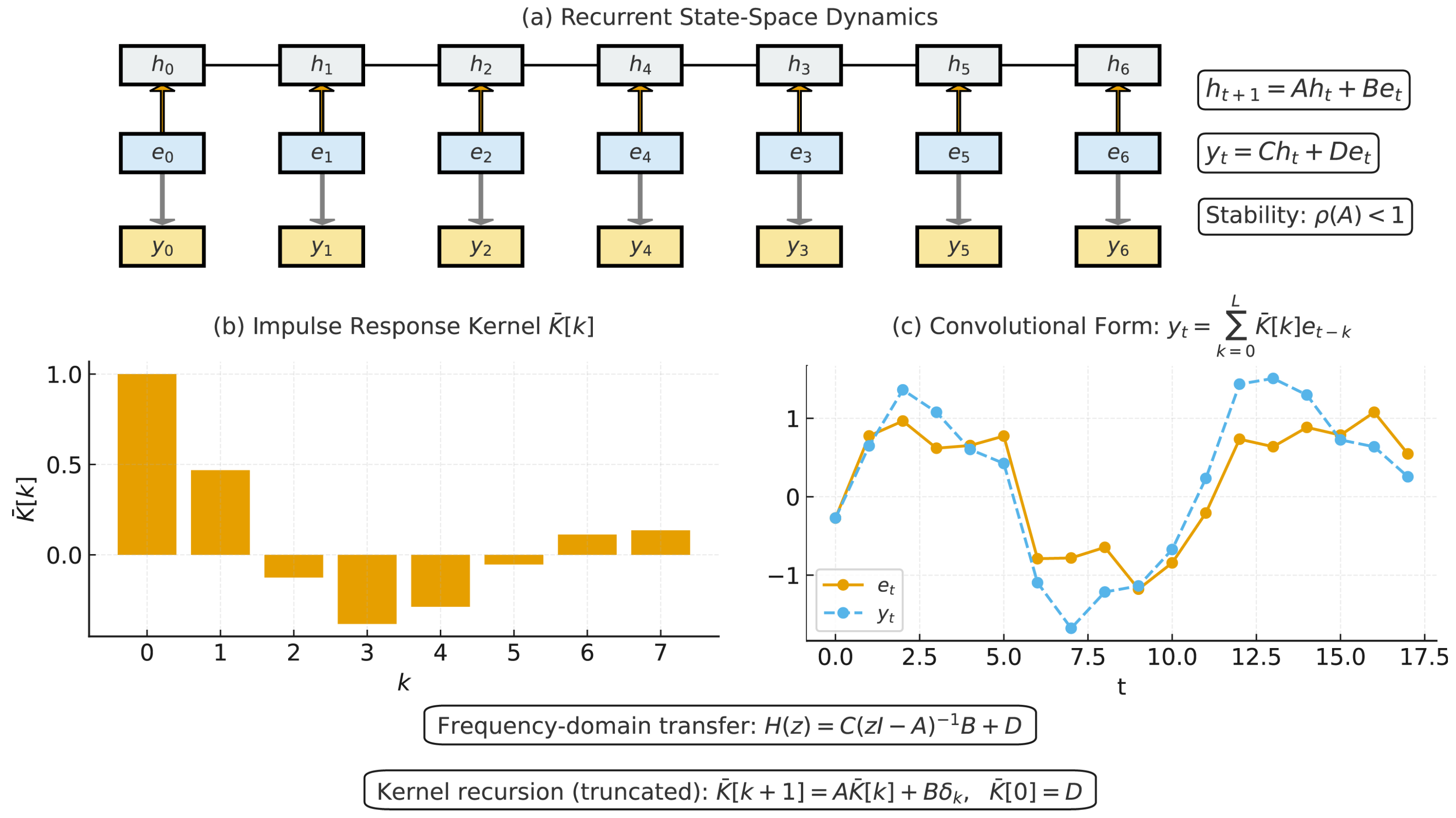

3.3. State–Space Model Encoder for Sequential Dependency Modeling

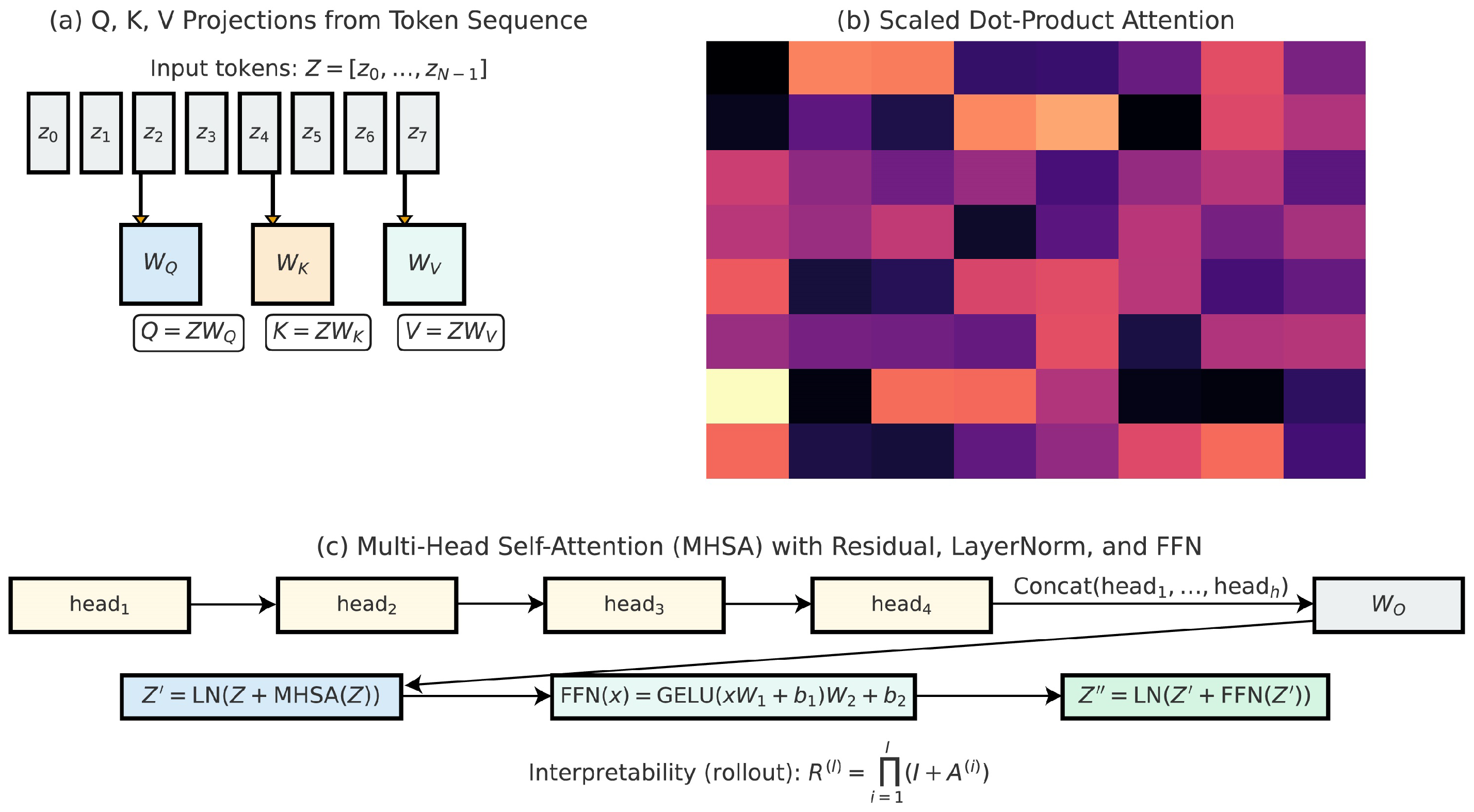

3.4. Vision Transformer Encoding for Global Contextual Reasoning

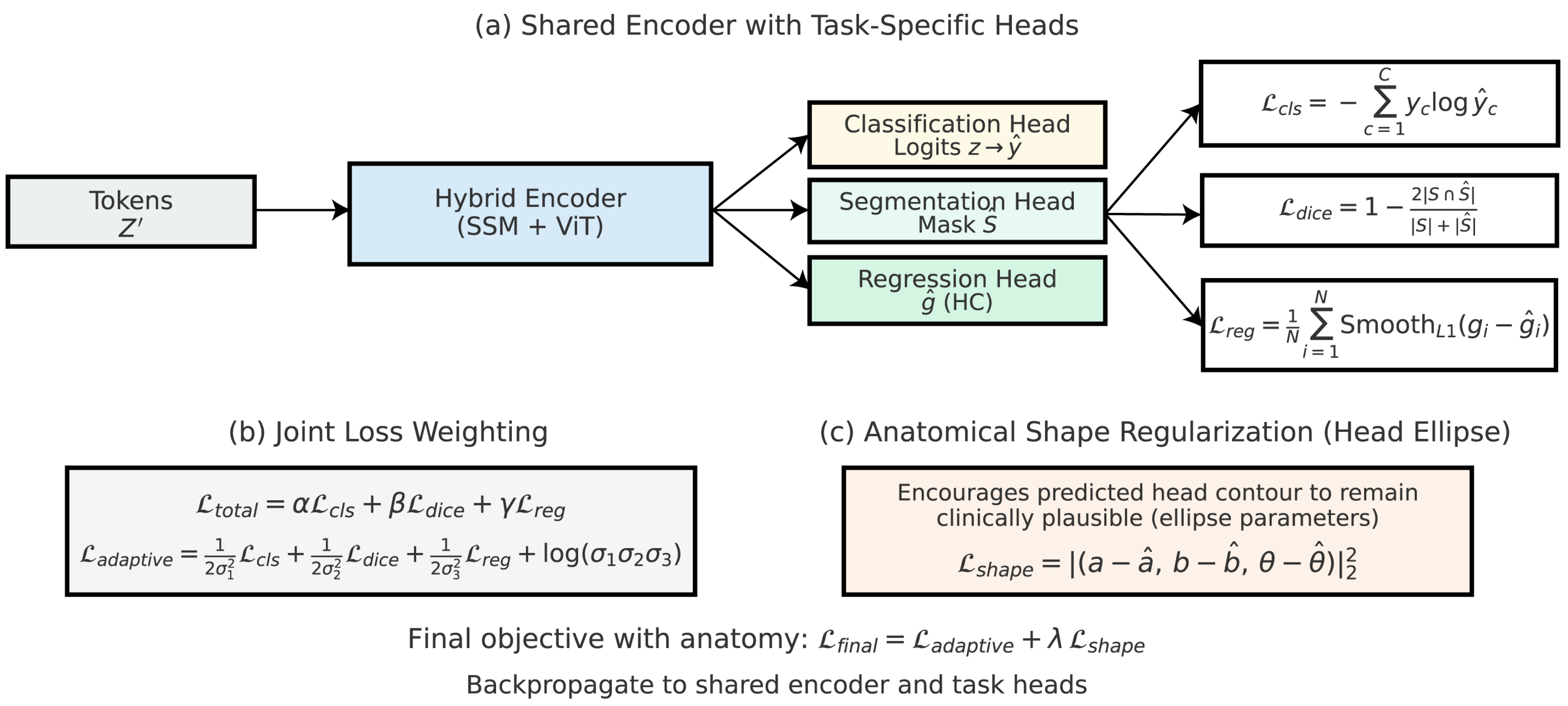

3.5. Multi-Task Learning with Anatomical Regularization

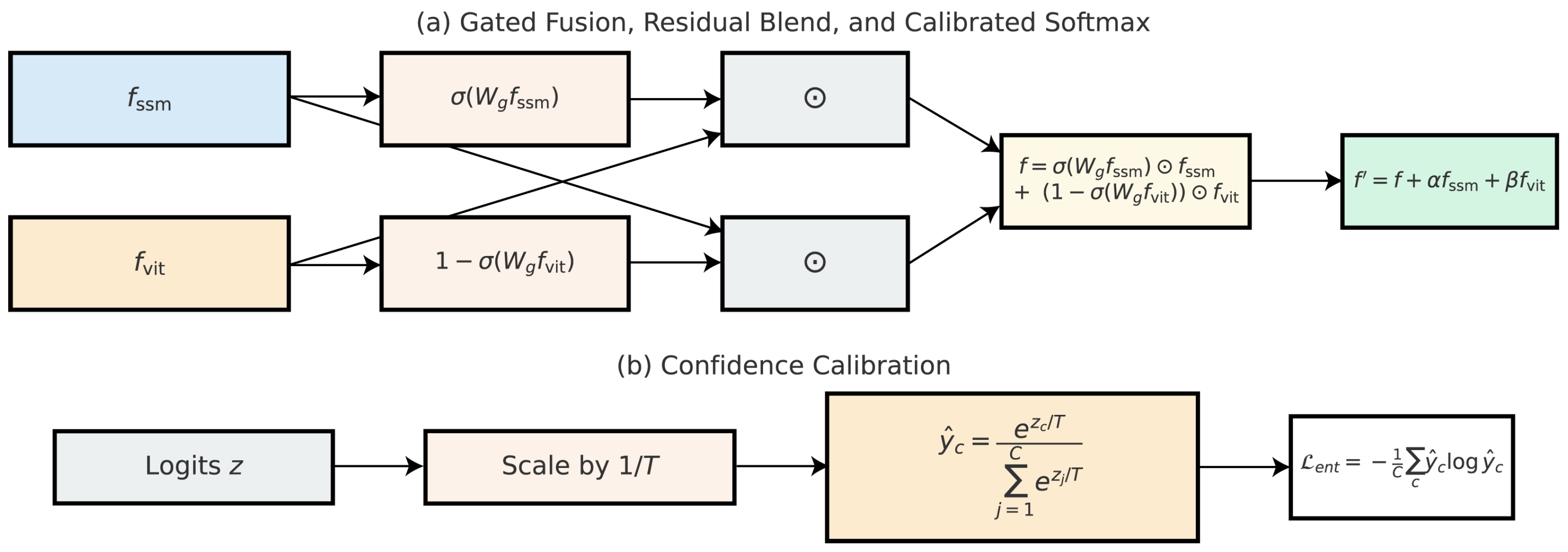

3.6. Decision Fusion and Confidence Calibration

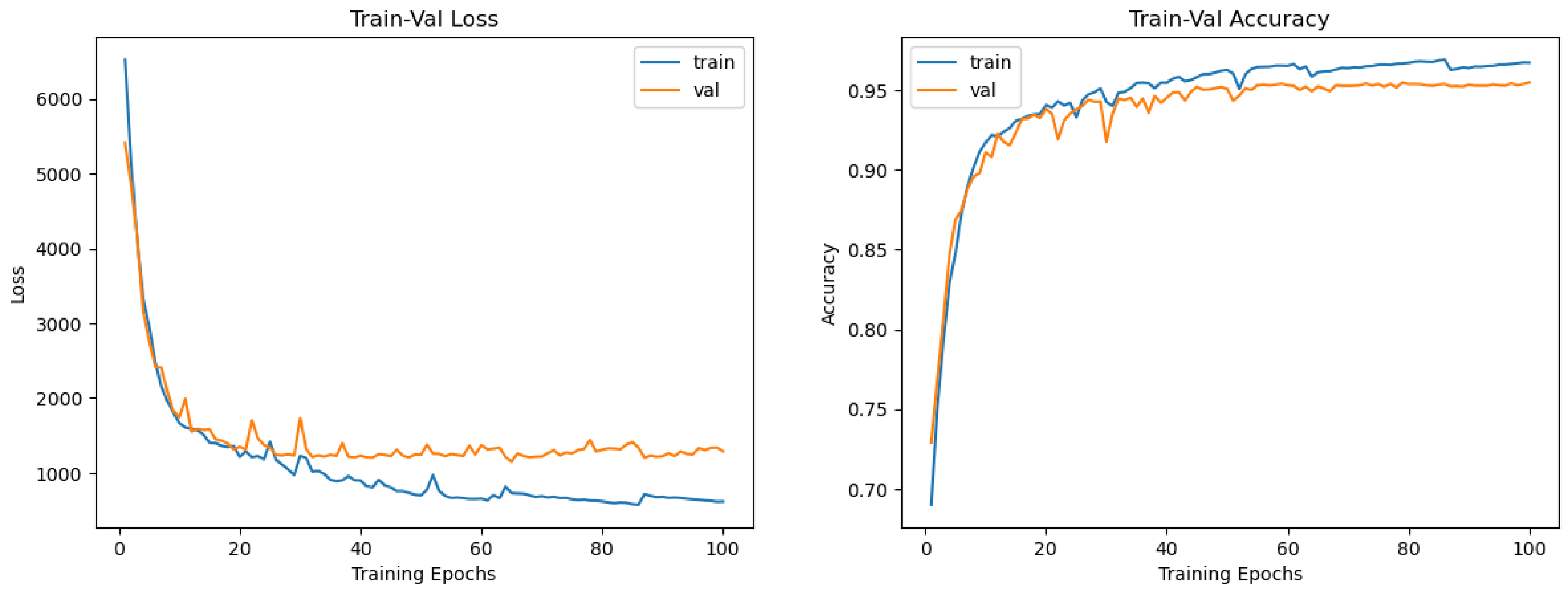

4. Experimental Results

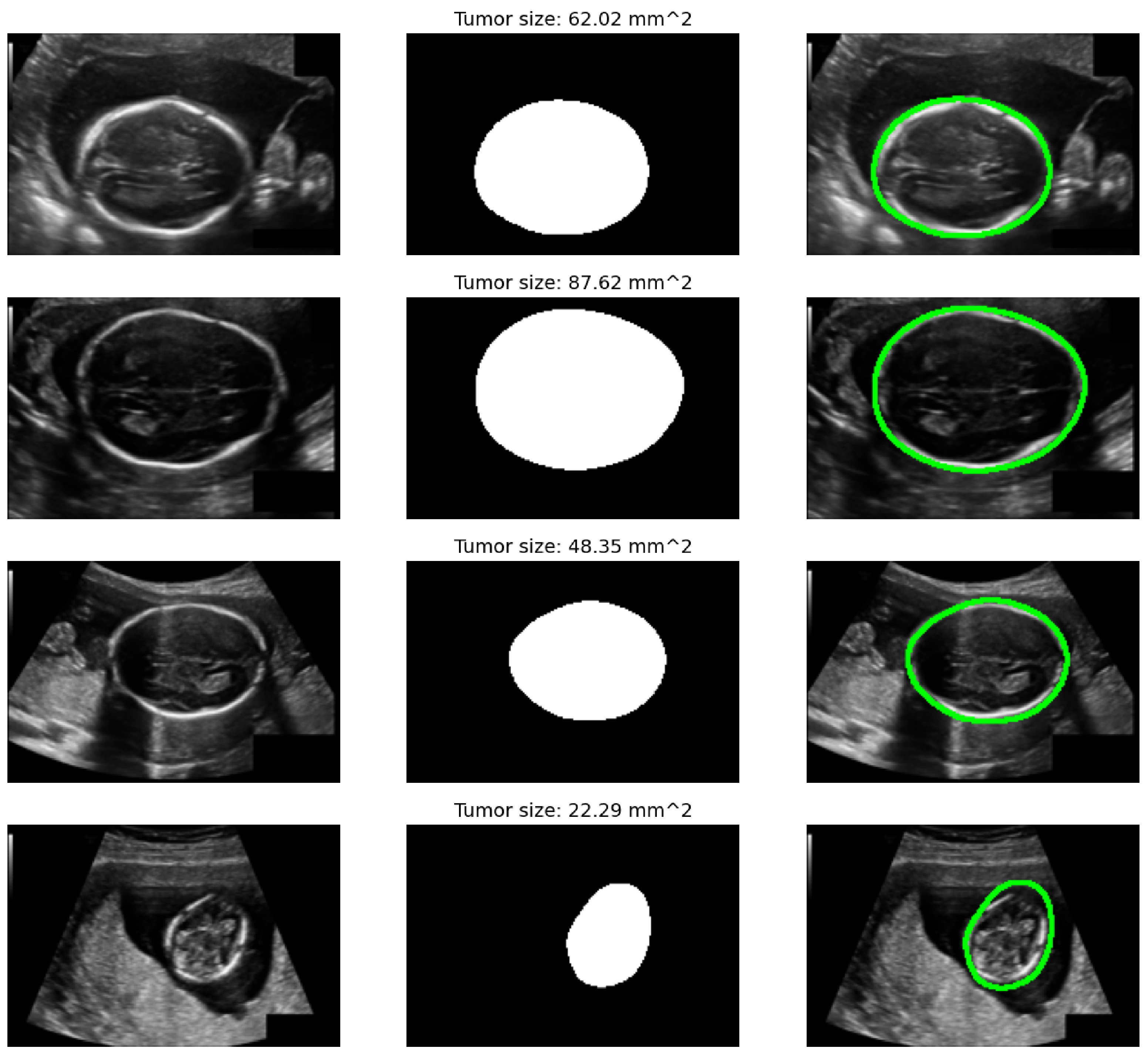

4.1. Datasets and Experimental Setup

4.2. Quantitative Results

4.3. Cross-Dataset Generalization

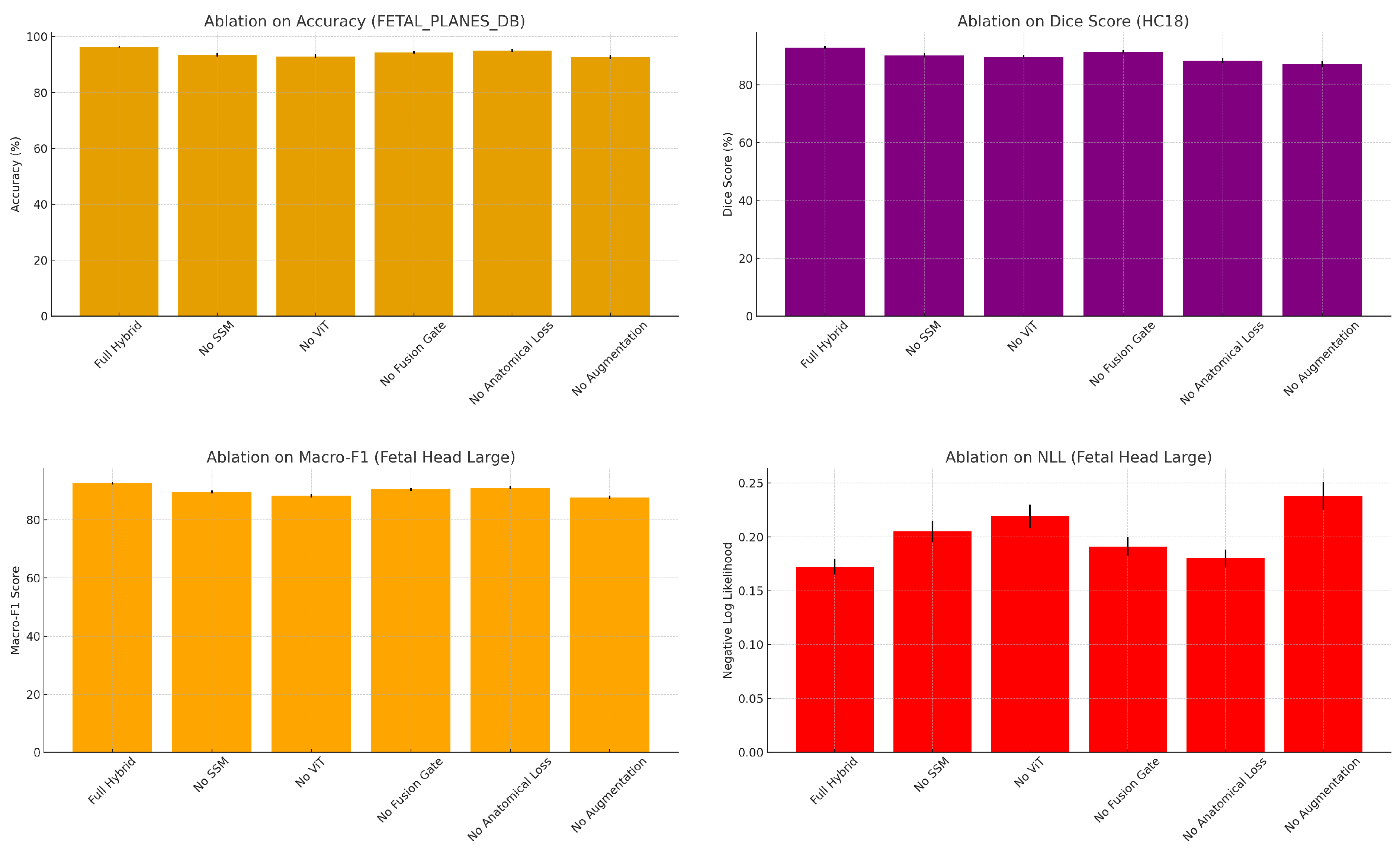

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.5. Statistical Testing

4.6. Runtime and Model Complexity

4.7. State-of-the-Art Comparison

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumgartner, C.F.; Kamnitsas, K.; Matthew, J.; Fletcher, T.P.; Smith, S.; Koch, L.M.; Kainz, B.; Rueckert, D. SonoNet: Real-time detection and localisation of fetal standard scan planes in freehand ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 2204–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Díaz, N.O.; Pérez-González, J.; Arámbula-Cosío, F.; Camargo-Marín, L.; Guzmán-Huerta, M.; Escalante-Ramírez, B.; Olveres-Montiel, J.; García-Ramírez, J.; Medina-Bañuelos, V.; Valdés-Cristerna, R. Automatic Standard Plane Detection in Fetal Ultrasound Improved by Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the Latin American Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Panama City, Panama, 2–5 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 368–377. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Chen, Q.; Guo, J.; Shi, R. Attention-guided context feature pyramid network for object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, G. Diffusion Vision Transformer of Temporomandibular Joint Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Software Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (SEAI), Xiamen, China, 21–23 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Yu, W.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Z.H.; Tay, F.E.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. Tokens-to-token vit: Training vision transformers from scratch on imagenet. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 558–567. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar]

- Linsley, D.; Karkada Ashok, A.; Govindarajan, L.N.; Liu, R.; Serre, T. Stable and expressive recurrent vision models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 10456–10467. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.M.; Malhi, H.S. Transfer learning with convolutional neural networks for classification of abdominal ultrasound images. J. Digit. Imaging 2017, 30, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Tan, G.; Wu, F.; Wen, H.; Li, K. Fetal ultrasound standard plane detection with coarse-to-fine multi-task learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 27, 5023–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, J.A.; Boukerroui, D. Ultrasound image segmentation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2006, 25, 987–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenster, A.; Downey, D.B.; Cardinal, H.N. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2001, 46, R67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Behnam, H.; Gifani, P. Ultrasound image analysis with vision transformers. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; Yang, D.; Myronenko, A.; Landman, B.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, D. Unetr: Transformers for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Warrington, A.; Linderman, S.W. Simplified state space layers for sequence modeling. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.04933. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual state space model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Ferrante, E.; Kamnitsas, K.; Heinrich, M.; Bai, W.; Caballero, J.; Cook, S.A.; De Marvao, A.; Dawes, T.; O’Regan, D.P.; et al. Anatomically constrained neural networks (ACNNs): Application to cardiac image enhancement and segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 37, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On calibration of modern neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu-Mizil, A.; Caruana, R. Predicting good probabilities with supervised learning. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Bonn, Germany, 7–11 August 2005; pp. 625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Liang, P.S.; Ma, T. Verified uncertainty calibration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, Granada, Spain, 20–20 September 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs | Time/Epoch (min) | Total (100 Epochs, h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal_Planes_DB | 11 | |||

| Fetal Head (Large) | 13 | |||

| HC18 | 8 |

| Dataset | Task | Classes | Train (Subjects/Images) | Val (Subjects/Images) | Test (Subjects/Images) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal_Planes_DB | Classification | 12 | 280/14,000 | 40/2000 | 80/4000 | 400/20,000 |

| Fetal Head (Large) | Classification + Regression | 6 | 350/17,500 | 50/2500 | 100/5000 | 500/25,000 |

| HC18 | Segmentation + Regression | 1 | 630/630 | 90/90 | 180/180 | 900/900 |

| Dataset | Model | Acc (%) | Macro-F1 (%) | Balanced Acc (%) | AUROC | NLL | ECE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FETAL_PLANES_DB | ResNet-50 | 92.1 ± 0.4 | 90.2 ± 0.5 | 90.8 ± 0.6 | 0.980 ± 0.003 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| ViT-B/16 | 94.3 ± 0.3 | 92.8 ± 0.4 | 93.1 ± 0.4 | 0.987 ± 0.002 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | |

| SSM-only | 93.5 ± 0.3 | 92.0 ± 0.4 | 92.4 ± 0.5 | 0.985 ± 0.002 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | |

| Hybrid (Ours) | 95.8 ± 0.3 | 94.9 ± 0.3 | 95.0 ± 0.3 | 0.992 ± 0.001 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | |

| Fetal Head (Large) | ResNet-50 | 90.5 ± 0.4 | 88.1 ± 0.5 | 88.9 ± 0.6 | 0.976 ± 0.003 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| ViT-B/16 | 92.6 ± 0.3 | 90.9 ± 0.4 | 91.2 ± 0.5 | 0.986 ± 0.002 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | |

| SSM-only | 92.0 ± 0.3 | 90.2 ± 0.4 | 90.6 ± 0.5 | 0.984 ± 0.002 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | |

| Hybrid (Ours) | 94.1 ± 0.3 | 92.8 ± 0.3 | 92.9 ± 0.4 | 0.989 ± 0.001 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | |

| Model | Dice (%) | IoU (%) | HD95 (mm) | MAE (mm) | RMSE (mm) | Corr | |

| HC18 | UNet baseline | 93.8 ± 0.4 | 88.3 ± 0.5 | 2.40 ± 0.18 | 2.90 ± 0.20 | 3.80 ± 0.25 | 0.962 ± 0.006 |

| ViT-only head | 94.6 ± 0.3 | 89.6 ± 0.4 | 2.10 ± 0.16 | 2.70 ± 0.18 | 3.60 ± 0.22 | 0.968 ± 0.005 | |

| SSM-only head | 94.8 ± 0.3 | 90.0 ± 0.4 | 2.00 ± 0.15 | 2.60 ± 0.17 | 3.50 ± 0.20 | 0.970 ± 0.005 | |

| Hybrid (Ours) | 95.7 ± 0.3 | 91.7 ± 0.3 | 1.70 ± 0.14 | 2.30 ± 0.16 | 3.20 ± 0.19 | 0.978 ± 0.004 |

| Model | FETAL_PLANES_DB Acc. (%) | Fetal Head (Large) Acc. (%) | HC18 Dice (%) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN–ViT | 6.5 | |||

| LSTM–ViT | 6.9 | |||

| SSM–ViT (Ours) | 6.6 |

| Training Dataset | Test Dataset | Model | Accuracy | Macro-F1 | Balanced Acc | AUROC | NLL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FETAL_PLANES_DB | Fetal Head (Large) | Hybrid | |||||

| ViT-only | |||||||

| SSM-only | |||||||

| Fetal Head (Large) | FETAL_PLANES_DB | Hybrid | |||||

| ViT-only | |||||||

| SSM-only |

| FETAL_PLANES_DB (Classification) | |||||

| Model Variant | Accuracy | Macro-F1 | Balanced Acc. | AUROC | NLL |

| Full Hybrid Model | |||||

| No SSM (ViT-only) | |||||

| No ViT (SSM-only) | |||||

| No Fusion Gate | |||||

| No Anatomical Loss | |||||

| No Augmentation | |||||

| Fetal Head (Large) (Classification + Circumference) | |||||

| Model Variant | Accuracy | Macro-F1 | Reg. MAE | Reg. Corr. | NLL |

| Full Hybrid Model | |||||

| No SSM (ViT-only) | |||||

| No ViT (SSM-only) | |||||

| No Fusion Gate | |||||

| No Anatomical Loss | |||||

| No Augmentation | |||||

| HC18 (Segmentation + Circumference) | |||||

| Model Variant | Dice (%) | Reg. MAE | Reg. MSE | Corr. | NLL |

| Full Hybrid Model | |||||

| No SSM (ViT-only) | |||||

| No ViT (SSM-only) | |||||

| No Fusion Gate | |||||

| No Anatomical Loss | |||||

| No Augmentation | |||||

| L | Accuracy (%) | Macro-F1 (%) | ECE (%) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 93.7 | 91.9 | 2.4 | 4.85 |

| 32 | 95.0 | 93.8 | 1.9 | 5.72 |

| 64 | 95.8 | 94.9 | 1.5 | 6.58 |

| 128 | 95.9 | 95.0 | 1.5 | 8.68 |

| L | Dice (%) | IoU (%) | MAE (mm) | ECE (%) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 93.6 | 88.7 | 2.74 | 2.7 | 4.90 |

| 32 | 94.8 | 90.3 | 2.48 | 2.1 | 5.80 |

| 64 | 95.7 | 91.7 | 2.30 | 1.8 | 6.62 |

| 128 | 95.8 | 91.8 | 2.28 | 1.8 | 8.73 |

| Dataset | Mean of g | Std of g |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal_Planes_DB | ||

| Fetal Head (Large) | ||

| HC18 |

| Dataset | No Preproc | Norm Only | Norm + CLAHE | Norm + CLAHE + Filter | Full (All Steps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal_Planes_DB | |||||

| Fetal Head (Large) | |||||

| HC18 (Dice %) |

| Component | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Latency (ms/img) | Incremental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ViT backbone only | 27 | Baseline global context | ||

| + SSM branch | 36 | M, GFLOPs, ms | ||

| + Fusion gate | 38 | M, GFLOPs, ms | ||

| + Anatomical decoder (aux) | 41 | M, GFLOPs, ms | ||

| + Calibration (softmax w/T) | 41 | Negligible params/compute | ||

| Total (no TTA) | Full model, single view | |||

| Total (with TTA, ) | Probability averaged over M views |

| FETAL_PLANES_DB (Classification) | |||||

| Model Comparison | Accuracy (p) | Macro-F1 (p) | Bal Acc (p) | AUROC (p) | NLL (p) |

| Hybrid vs. ViT-only | 0.003 ** | 0.005 ** | 0.007 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.002 ** |

| Hybrid vs. SSM-only | 0.001 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.001 *** |

| Hybrid vs. No Fusion | 0.041 * | 0.035 * | 0.038 * | 0.030 * | 0.029 * |

| Hybrid vs. No Anatomy | 0.048 * | 0.042 * | 0.045 * | 0.037 * | 0.025 * |

| Hybrid vs. No Augment | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.000 *** |

| Fetal Head (Large) (Classification + Circumference) | |||||

| Model Comparison | Accuracy (p) | Macro-F1 (p) | Reg. MAE (p) | Reg. Corr (p) | NLL (p) |

| Hybrid vs. ViT-only | 0.004 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.009 ** | 0.013 * | 0.005 ** |

| Hybrid vs. SSM-only | 0.001 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.007 ** | 0.012 * | 0.002 ** |

| Hybrid vs. No Fusion | 0.038 * | 0.040 * | 0.033 * | 0.030 * | 0.041 * |

| Hybrid vs. No Anatomy | 0.026 * | 0.029 * | 0.032 * | 0.027 * | 0.022 * |

| Hybrid vs. No Augment | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** |

| HC18 (Segmentation + Circumference) | |||||

| Model Comparison | Dice (p) | Reg. MAE (p) | Reg. MSE (p) | Corr. (p) | |

| Hybrid vs. ViT-only | 0.005 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.007 ** | |

| Hybrid vs. SSM-only | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.006 ** | |

| Hybrid vs. No Fusion | 0.029 * | 0.030 * | 0.031 * | 0.034 * | |

| Hybrid vs. No Anatomy | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.002 ** | |

| Hybrid vs. No Augment | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | |

| Model Variant | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Runtime (ms) | Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Hybrid Model | 34.2 | 6.58 | 42.5 | 1120 |

| No SSM (ViT-only) | 28.7 | 5.91 | 38.6 | 1030 |

| No ViT (SSM-only) | 25.4 | 4.73 | 35.2 | 990 |

| No Fusion Gate | 32.8 | 6.42 | 40.7 | 1104 |

| No Anatomical Loss | 34.2 | 6.58 | 42.3 | 1120 |

| No Augmentation | 34.2 | 6.58 | 42.1 | 1119 |

| Dataset | Method | Accuracy | Macro-F1 | Dice/MAE | Correlation | NLL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FETAL_PLANES_DB | SonoNet [1] | 90.1 | 0.798 | – | – | – |

| Att-CNN [2] | 96.25 | 0.9576 | – | – | – | |

| ACNet [3] | 95.4 | 0.941 | – | – | – | |

| Diffusion-ViT [5] | 95.9 | 0.949 | – | – | – | |

| Ours (Hybrid) | 96.3 | 0.952 | – | – | 0.161 | |

| Fetal Head (Large) | ResNet-50 Baseline [4] | 91.2 | 0.881 | 2.42 | 0.92 | 0.238 |

| ACNet [3] | 92.7 | 0.912 | 2.12 | 0.94 | – | |

| Diffusion-ViT [5] | 93.8 | 0.924 | 2.03 | 0.95 | – | |

| Ours (Hybrid) | 94.6 | 0.927 | 1.95 | 0.96 | 0.172 | |

| HC18 | UNet++ [25] | – | – | 89.7 | 0.93 | – |

| Attention U-Net [26] | – | – | 90.2 | 0.94 | – | |

| TransUNet [17] | – | – | 91.0 | 0.95 | – | |

| Ours (Hybrid) | – | – | 92.8 | 0.97 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tehsin, S.; Alshaya, H.; Bouchelligua, W.; Nasir, I.M. Hybrid State–Space and Vision Transformer Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification in Prenatal Diagnostics. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222879

Tehsin S, Alshaya H, Bouchelligua W, Nasir IM. Hybrid State–Space and Vision Transformer Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification in Prenatal Diagnostics. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222879

Chicago/Turabian StyleTehsin, Sara, Hend Alshaya, Wided Bouchelligua, and Inzamam Mashood Nasir. 2025. "Hybrid State–Space and Vision Transformer Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification in Prenatal Diagnostics" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222879

APA StyleTehsin, S., Alshaya, H., Bouchelligua, W., & Nasir, I. M. (2025). Hybrid State–Space and Vision Transformer Framework for Fetal Ultrasound Plane Classification in Prenatal Diagnostics. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2879. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222879