Screening Beyond Dependence: At-Risk Drinking and Psychosocial Correlates in the Heart Transplant Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

3. Results

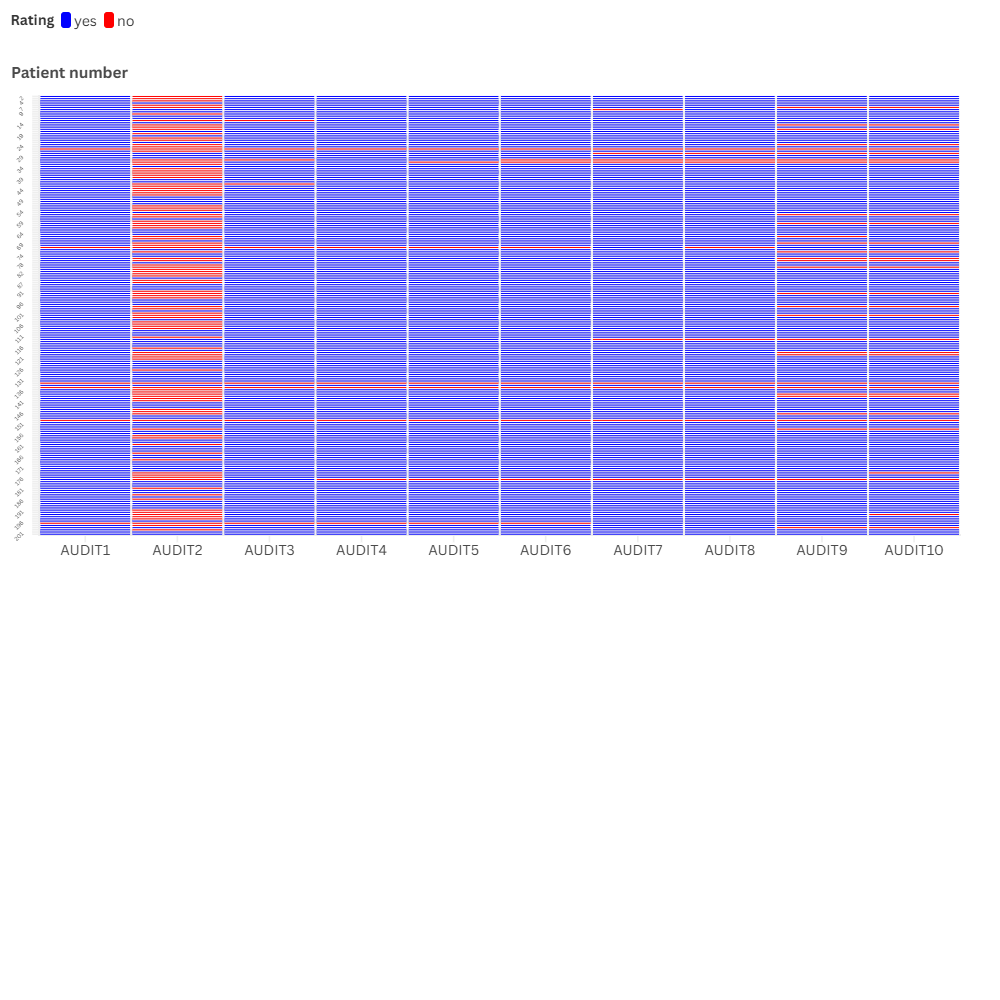

3.1. Scorability of the Questionnaires

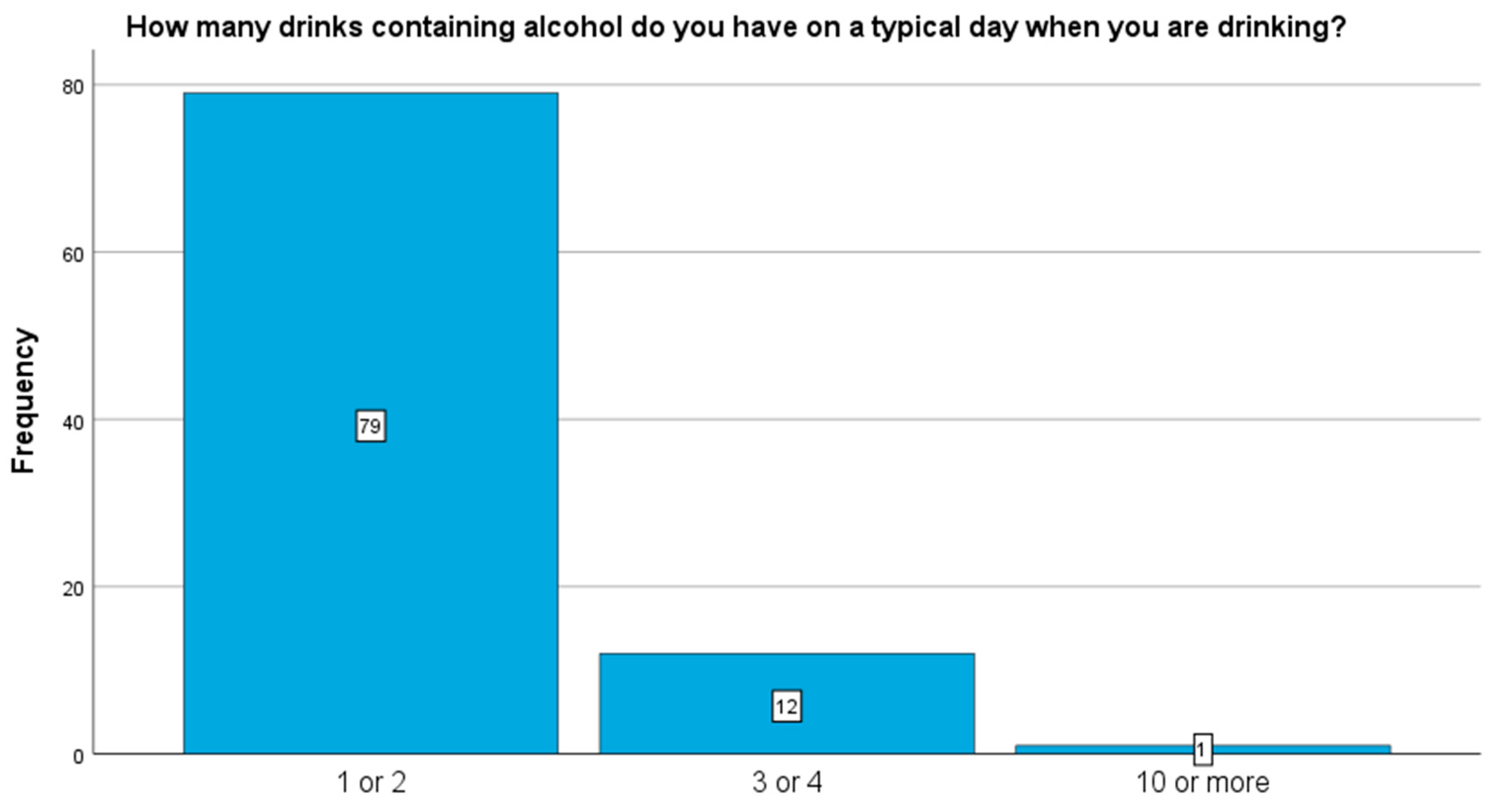

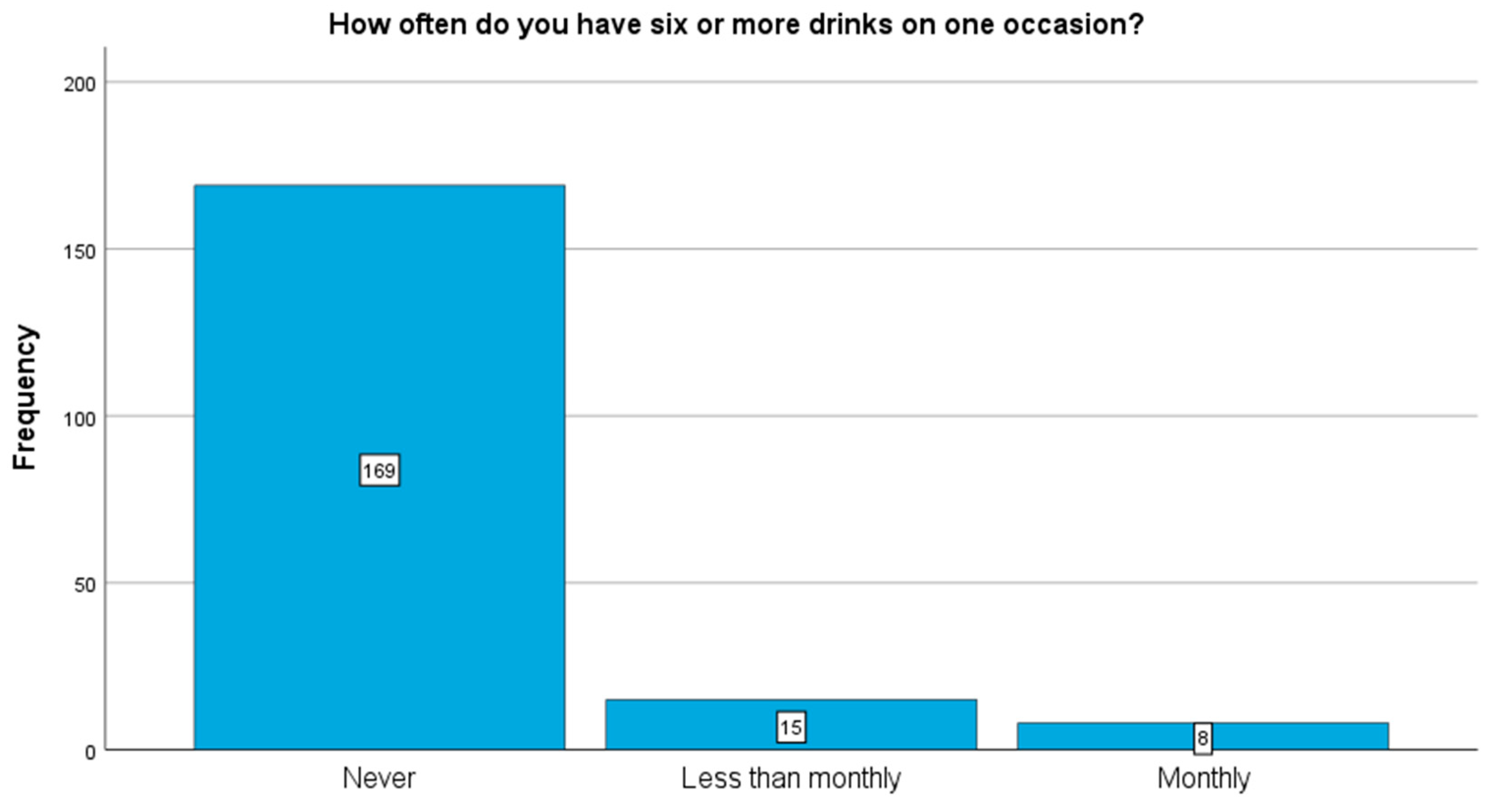

3.2. Descriptive Results

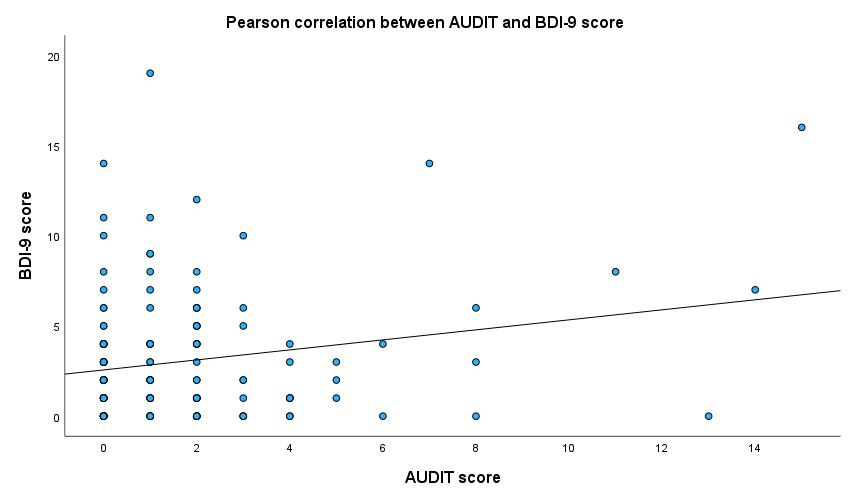

3.3. Correlations

3.4. Multivariate Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUDIT | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| AUDIT-C | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption |

| BRIEF | Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool |

| MARS-5 | Medication Adherence Report Scale |

| BDI-9 | 9-item Beck Depression Inventory |

| AUD | Alcohol Use Disorder |

Appendix A

References

- Fuchs, F.D.; Fuchs, S.C. The Effect of Alcohol on Blood Pressure and Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2021, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlund, I.M.; Cunningham, H.A.; Tikkanen, A.L.; Bigalke, J.A.; Smoot, C.A.; Durocher, J.J.; Carter, J.R. Morning sympathetic activity after evening binge alcohol consumption. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H305–H315, Erratum in Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H1061–H1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krittanawong, C.; Isath, A.; Rosenson, R.S.; Khawaja, M.; Wang, Z.; Fogg, S.E.; Virani, S.S.; Qi, L.; Cao, Y.; Long, M.T.; et al. Alcohol Consumption and Cardiovascular Health. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskoboinik, A.; Prabhu, S.; Ling, L.H.; Kalman, J.M.; Kistler, P.M. Alcohol and Atrial Fibrillation: A Sobering Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2567–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.O.; Berdzuli, N.; Ilbawi, A.; Kestel, D.; Kluge, H.P.; Krech, R.; Mikkelsen, B.; Neufeld, M.; Poznyak, V.; Rekve, D.; et al. Health and cancer risks associated with low levels of alcohol consumption. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhalle, L.; Van Bockstaele, K.; Duerinckx, N.; Vanhoof, J.; Dierickx, K.; Neyens, L.; Van Cleemput, J.; Gryp, S.; Kums, D.; De Bondt, K.; et al. How to Screen for at Risk Alcohol Use in Transplant Patients? From Instrument Selection to Implementation of The Audit-C. Clin. Transpl. 2021, 35, e14137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, Y.; Ducharme, A.; Kittleson, M.; Bansal, N.; Stehlik, J.; Amdani, S.; Saeed, D.; Cheng, R.; Clarke, B.; Dobbels, F.; et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the Evaluation and Care of Cardiac Transplant Candidates—2024. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2024, 43, 1529–1628.e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, M.A.; Dimartini, A.F.; Dobbels, F.; Grady, K.L.; Jowsey-Gregoire, S.G.; Kaan, A.; Kendall, K.; Young, Q.-R.; Abbey, S.E.; Butt, Z.; et al. The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW Recommendations for the Psychosocial Evaluation of Adult Cardiothoracic Transplant Candidates and Candidates for Long-term Mechanical Circulatory Support. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2018, 37, 803–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Armstrong, M.J.; Corbett, C.; Day, E.J.; Neuberger, J.M. Alcohol and substance abuse in solid-organ transplant recipients. Transplant 2013, 96, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, Text Revision, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sirri, L.; Potena, L.; Masetti, M.; Tossani, E.; Grigioni, F.; Magelli, C.; Branzi, A.; Grandi, S. Prevalence of Substance-Related Disorders in Heart Transplantation Candidates. Transpl. Proc. 2007, 39, 1970–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, M.A.; DiMartini, A.F.; Steel, J.; De Vito Dabbs, A.; Myaskovsky, L.; Unruh, M.; Greenhouse, J. Meta-Analysis of Risk for Relapse to Substance Use After Transplantation of the Liver or Other Solid Organs. Liver Transpl. 2008, 14, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, J.S.; Eberly, C.; Mohanty, P.K. Substance abuse in heart transplant recipients: A 10-year follow-up study. Prog. Transpl. 2001, 11, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbels, F.; Denhaerynck, K.; Klem, M.L.; Sereika, S.M.; De Geest, S.; De Simone, P.; Berben, L.; Binet, I.; Burkhalter, H.; Drent, G.; et al. Correlates and outcomes of alcohol use after single solid organ transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl. Rev. 2019, 33, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Zweben, A.; Carlo DiClemente, D.C.; Rychtarik, R.G.; Mattson, M.E. Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Project MATCH Monograph Series; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1999; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Mcdonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rózsa, S.; Szádóczky, E.; Füredi, J. Psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the shortened Beck Depression Inventory. Psychiatr. Hung. 2001, 16, 384–402. [Google Scholar]

- Haun, J.; Noland-Dodd, V.; Varnes, J.; Graham-Pole, J.; Rienzo, B.; Donaldson, P. Testing the BRIEF Health Literacy Screening Tool. Fed. Pract. 2009, 26, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: A measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodensky, C.A.; Golin, C.E.; Ochtera, R.D.; Turner, B.J. Systematic review: Effect of alcohol intake on adherence to outpatient medication regimens for chronic diseases. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2012, 73, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daeppen, J.B.; Yersin, B.; Landry, U.; Pécoud, A.; Decrey, H. Reliability and Validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Imbedded Within a General Health Risk Screening Questionnaire: Results of a Survey in 332 Primary Care Patients. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Imtiaz, S.; Neufeld, M. Quantifying the contribution of alcohol to cardiomyopathy: A systematic review. Alcohol 2017, 61, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagrosek, A.; Messroghli, D.; Aiche, S.; Schulz, O.; Bohl, S.; Wassmuth, R.; Rudolph, A.; Dietz, R.; Schulz-Menger, J. Acute alcohol-induced myocardial inflammation as visualized by cardiac magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2011, 13 (Suppl. S1), M4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivukoski, U.; Bloigu, A.; Bloigu, R.; Aalto, M.; Laatikainen, T.; Niemelä, O. Liver enzymes in alcohol consumers with or without binge drinking. Alcohol 2019, 78, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staatz, C.E.; Tett, S.E. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Tacrolimus in Solid Organ Transplantation. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.; Britton, A.; Kubinova, R.; Malyutina, S.; Pajak, A.; Nikitin, Y.; Bobak, M. Drinking Pattern, Abstention and Problem Drinking as Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms: Evidence from Three Urban Eastern European Populations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschloo, L.; Vogelzangs, N.; Smit, J.H.; Van Den Brink, W.; Veltman, D.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The performance of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) in detecting alcohol abuse and dependence in a population of depressed or anxious persons. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guertler, D.; Moehring, A.; Krause, K.; Batra, A.; Eck, S.; Freyer-Adam, J.; Ulbricht, S.; Rumpf, H.J.; Bischof, G.; John, U.; et al. Copattern of depression and alcohol use in medical care patients: Cross sectional study in Germany. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velleca, A.; Shullo, M.A.; Dhital, K.; Azeka, E.; Colvin, M.; DePasquale, E.; Farrero, M.; García-Guereta, L.; Jamero, G.; Khush, K.; et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2023, 42, e1–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.; Sears, S.F.; Åsenlöf, P.; Berry, K. Psychologically informed health care. Transl. Behav. Med. 2023, 13, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollenberger, C.H.; Chang, H.R.; Lim, J.; Shaik, M.R.; Blaney, H.; Mathur, V.; Terry, N.; Luk, J.W.; Diazgranados, N.; Hsu, C.C. Psychosocial therapy improves outcomes for alcohol use disorder in people with chronic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0805. [Google Scholar]

- Leyde, S.; Abbs, E.; Suen, L.W.; Martin, M.; Mitchell, A.; Davis, J.; Azari, S. A Mixed-methods Evaluation of an Addiction/Cardiology Pilot Clinic with Contingency Management for Patients with Stimulant-associated Cardiomyopathy. J. Addict. Med. 2023, 17, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Sex | n (%) |

| Male | 152 (75.60) |

| Female | 49 (24.40) |

| Age, years (mean ± SD; min, max) | 56.33 ± 11.46 (min. 19, max. 80) |

| Time since transplant, years (mean ± SD; min, max) | 6.37 ± 4.04 (min. 0, max. 27) |

| Years spent in education, years (mean ± SD; min, max) | 13.31 ± 3.33 (min. 3, max. 25) |

| Relationship status | n (%) |

| Married or in a relationship | 142 (70.64) |

| No partner | 58 (28.86) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) |

| Health-related variables | Mean ± SD (min, max) |

| BRIEF score | 9.60 ± 2.24 (min. 2, max. 12) |

| Modified MARS-5 score | 24.58 ± 1.16 (min. 14, max. 25) |

| BDI-9 score | 2.90 ± 3.31 (min. 0, max. 19) |

| AUDIT Score | AUDIT Category | % (n) | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Abstinent | 41.0% (n = 66) | - | - | - |

| 1–7 | Low-risk | 54.7% (n = 88) | 2.14 ± 1.35 | 1 | 7 |

| 8–15 | Medium-risk | 4.3% (n = 7) | 11.00 ± 3.06 | 8 | 15 |

| >15 | High-risk | 0% (n = 0) | - | - | - |

| AUDIT-C Score | AUDIT-C Category | % (n) | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 (female) 0–3 (male) | No risk | 93.1% (n = 176) | 0.73 ± 0.94 | 0 | 3 |

| >2 (female) >3 (male) | At-risk | 6.9% (n = 13) | 5.08 ± 1.32 | 3 | 8 |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 17.903 | 4.431 | — | 4.040 | <0.001 |

| Sex (1 = male, 0 = female) | 1.048 | 0.496 | 0.185 | 2.111 | 0.037 |

| In a relationship (1 = yes) | 0.023 | 0.472 | 0.004 | 0.049 | 0.961 |

| Years of education | 0.035 | 0.071 | 0.044 | 0.491 | 0.624 |

| BDI-9 score | 0.050 | 0.072 | 0.071 | 0.691 | 0.491 |

| MARS-5 score | −0.673 | 0.162 | −0.373 | −4.161 | <0.001 |

| BRIEF 3-item total | −0.114 | 0.118 | −0.096 | −0.965 | 0.337 |

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 7.188 | 2.534 | — | 2.836 | 0.005 |

| Sex (1 = male, 0 = female) | 0.722 | 0.268 | 0.224 | 2.694 | 0.008 |

| In a relationship (1 = yes) | 0.106 | 0.253 | 0.035 | 0.418 | 0.676 |

| Years of education | 0.048 | 0.039 | 0.106 | 1.253 | 0.212 |

| BDI-9 score | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.060 | 0.614 | 0.540 |

| MARS-5 score | −0.288 | 0.093 | −0.263 | −3.104 | 0.002 |

| BRIEF 3-item total | −0.042 | 0.061 | −0.065 | −0.697 | 0.487 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Assabiny, A.; Ocsovszky, Z.; Ehrenberger, B.; Papp-Zipernovszky, O.; Otohal, J.; Marjai, K.; Rácz, J.; Merkely, B.; Dávid, B. Screening Beyond Dependence: At-Risk Drinking and Psychosocial Correlates in the Heart Transplant Population. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212812

Assabiny A, Ocsovszky Z, Ehrenberger B, Papp-Zipernovszky O, Otohal J, Marjai K, Rácz J, Merkely B, Dávid B. Screening Beyond Dependence: At-Risk Drinking and Psychosocial Correlates in the Heart Transplant Population. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(21):2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212812

Chicago/Turabian StyleAssabiny, Alexandra, Zsófia Ocsovszky, Blanka Ehrenberger, Orsolya Papp-Zipernovszky, József Otohal, Kamilla Marjai, József Rácz, Béla Merkely, and Beáta Dávid. 2025. "Screening Beyond Dependence: At-Risk Drinking and Psychosocial Correlates in the Heart Transplant Population" Diagnostics 15, no. 21: 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212812

APA StyleAssabiny, A., Ocsovszky, Z., Ehrenberger, B., Papp-Zipernovszky, O., Otohal, J., Marjai, K., Rácz, J., Merkely, B., & Dávid, B. (2025). Screening Beyond Dependence: At-Risk Drinking and Psychosocial Correlates in the Heart Transplant Population. Diagnostics, 15(21), 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212812