Vesicovaginal Leiomyoma at 20 Years of Age—A Rare Clinical Entity: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient History

2.2. Physical Examination

2.3. Initial Investigations

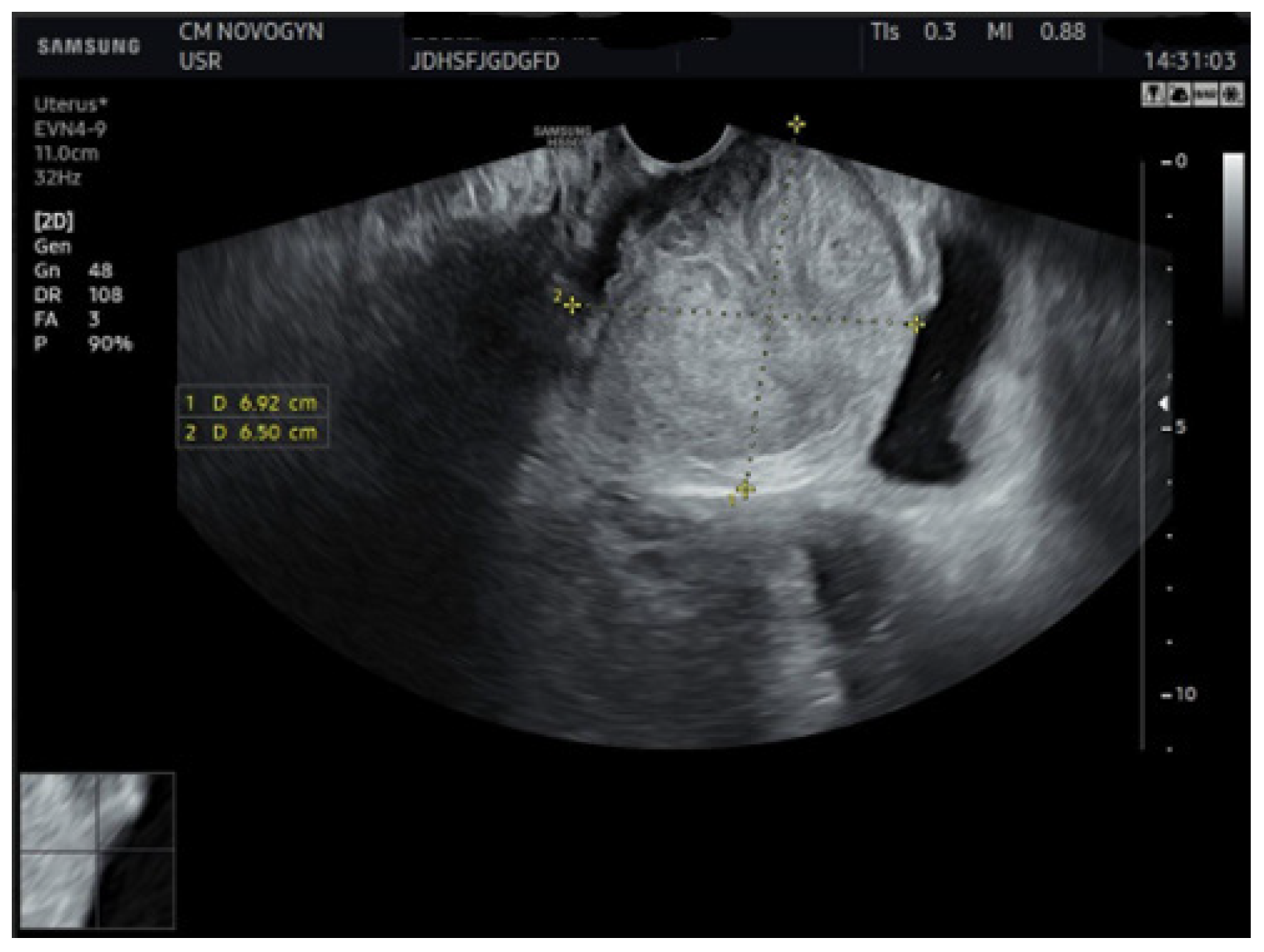

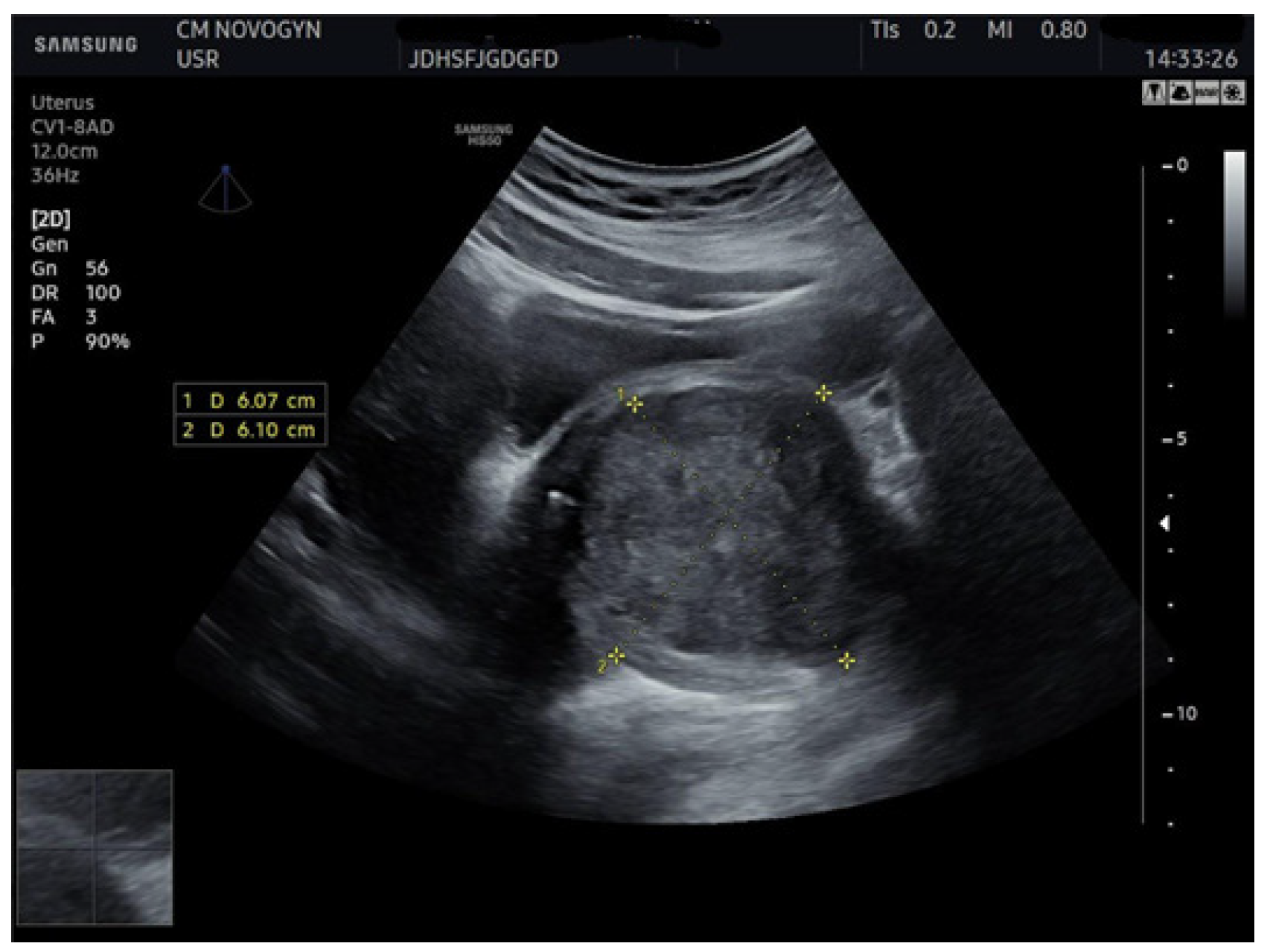

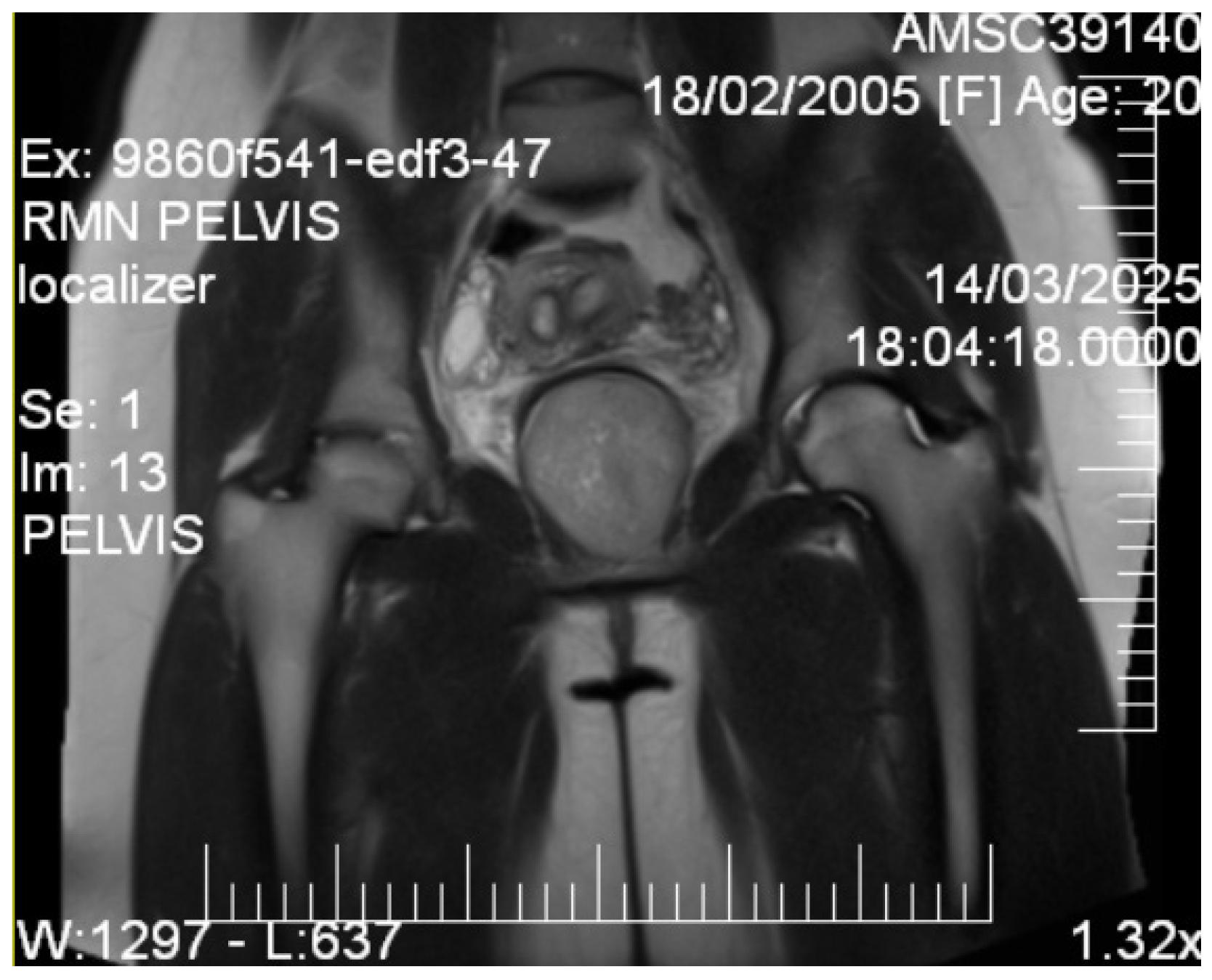

2.4. Imaging Studies

2.5. Tissue Sampling

2.6. Histopathological Analysis

2.7. Management and Outcome

2.7.1. Preoperative Planning

2.7.2. Surgical Intervention

2.7.3. Intraoperative Findings

2.7.4. Postoperative Course

2.7.5. Follow-Up and Outcome

3. Discussion

3.1. Imaging Characteristics and Diagnostic Precision

3.2. Management Evolution and Surgical Considerations

3.3. Differential Diagnosis and Rationale

3.4. Malignant Considerations

3.5. Benign Considerations

3.6. Diagnostic Rationale

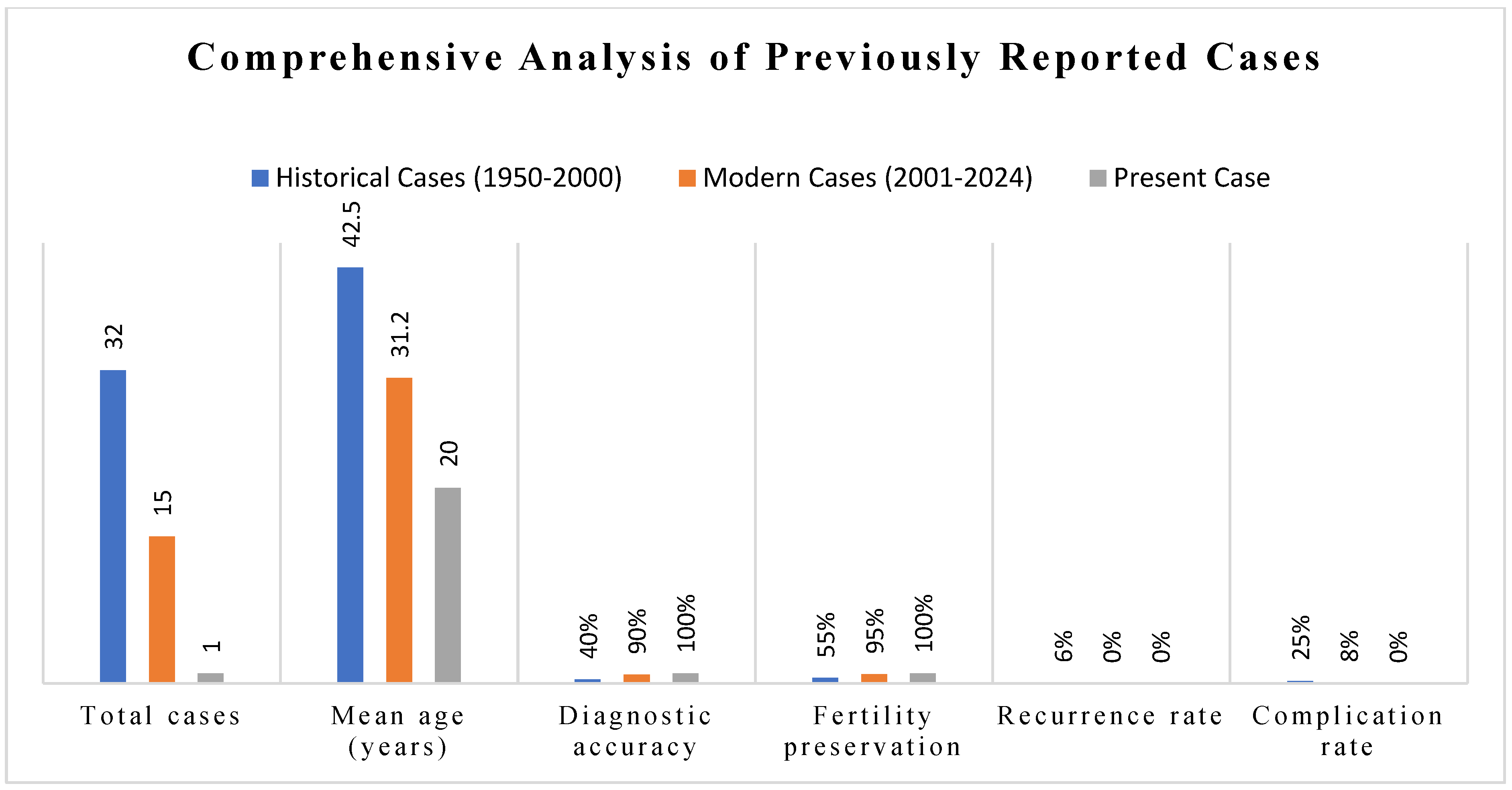

4. Literature Synthesis and Comparative Analysis

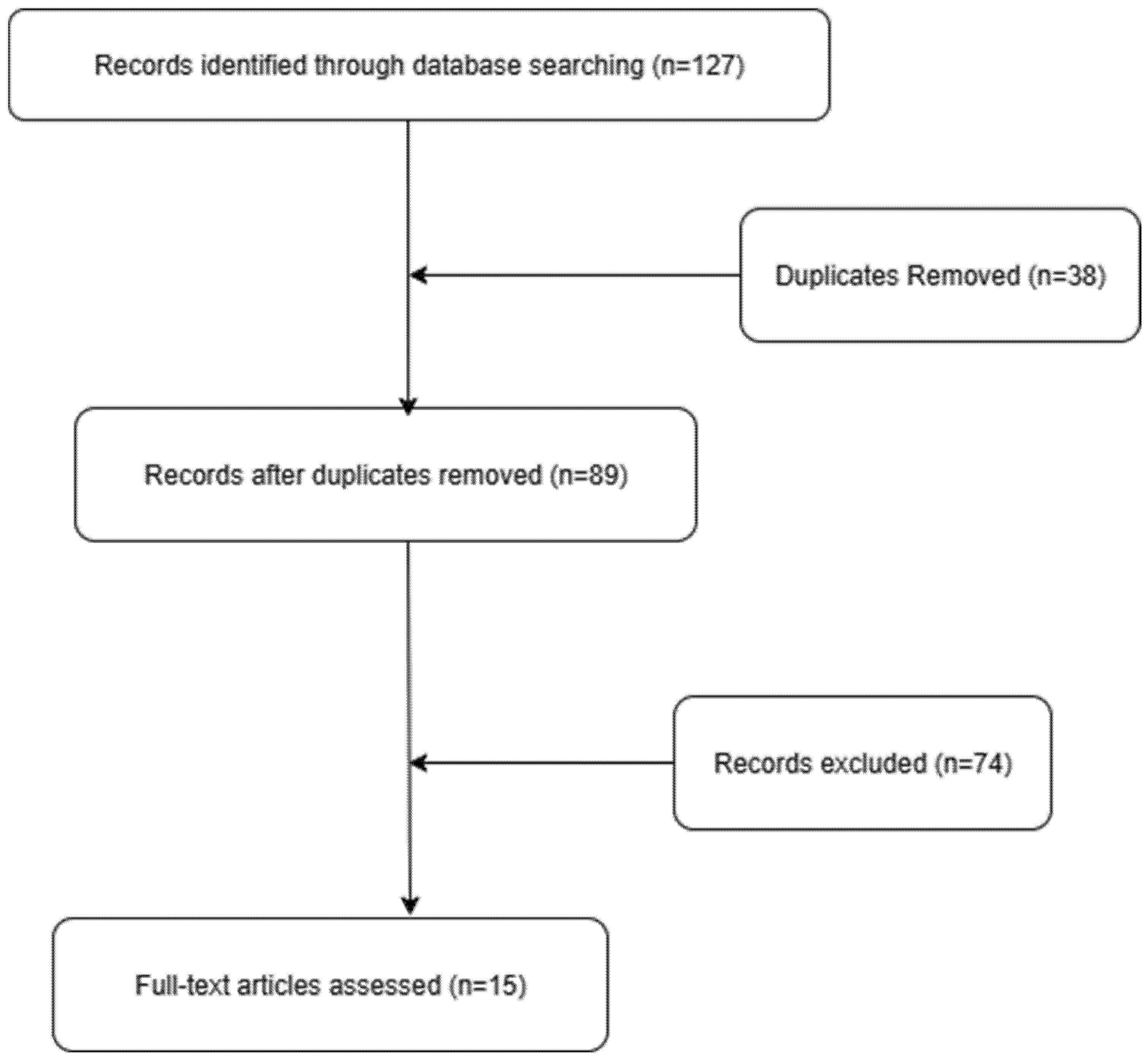

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Comprehensive Overview of Reported Cases

4.3. Synthesis of Clinical Characteristics

- •

- •

- •

- •

- Vaginal bleeding: Reported in 35% of cases, typically irregular and associated with larger masses.

- •

- Asymptomatic presentation: Only 8% of cases are usually discovered incidentally during routine examination.

- Physical Examination Findings:

- Palpable vaginal mass: Universal finding (100% of cases).

- Mass consistency: Uniformly described as firm, smooth, and well-defined (95% of cases).

- Cervical displacement: Reported in 55% of cases with masses >6 cm.

4.4. Diagnostic Approaches and Accuracy

4.5. Management Strategies and Surgical Approaches

- Historical approach (1950–1980): Primarily radical excision with frequent hysterectomy (45% of cases).

- Transitional period (1980–2000): Introduction of conservative approaches with organ preservation (70% of cases) [36].

- Modern era (2000–present): Fertility-preserving surgery as standard of care (95% of cases) [32].

- Surgical Approach Distribution:

- Transvaginal enucleation: 55% of modern cases (preferred approach for accessible lesions).

- Combined laparoscopic–vaginal: 25% of cases (for large or deep pelvic masses).

- Transabdominal approach: 15% of cases (historical or complex cases).

- Laparoscopic only: 5% of cases (small, pedunculated lesions).

4.6. Complications and Morbidity Analysis

- Urethral injury: 3% of cases (primarily in transvaginal approaches).

- Significant hemorrhage (>500 mL): 5% of cases.

- Conversion to open surgery: 12% of laparoscopic attempts.

- Postoperative Complications:

- Urinary retention: 15% of cases (temporary in 90%) [36].

- Wound dehiscence: 5% of cases (vaginal approach).

- Infection: 3% of cases.

- Chronic pain: 2% of cases (all resolved within 6 months).

4.7. Long-Term Outcomes and Follow-Up Data

- Successful pregnancies: 20 women (80%) [32].

- Pregnancy complications: None attributed to previous surgery.

- Delivery complications: One case of prolonged labor, no other problems.

- Long-Term Functional (LTO) Outcomes:

4.8. Positioning of Current Case Within Literature Context

- Significance of Age: 20 years is among the youngest ages in the current literature with a detailed diagnostic work up.

- Related abnormalities: Recording related concomitant septate uterus helps interpret possible developmental associations [11].

4.9. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

4.10. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Patient Perspective

“I could not sleep days after doctors told me that I had cancer. The health professionals explained everything regarding the process that they were to perform. I was healing faster than I expected, and it did surprise me how fast I began to feel better. In two months, I was back to my normal sexual practices with my UTI symptoms completely resolved. I am pleased that they could solve the issue without interfering with my future intentions of having children.”

- Learning Points/Teaching Highlights

- Vesicovaginal leiomyomas are observed in young women.

- MRI is decisive in characterizing tissues.

- Preoperative diagnostics with biopsy.

- Transvaginal enucleation preserves fertility.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| DWI | diffusion-weighted imaging |

| Beta hCG | beta human chorionic gonadotropin |

| ADC | apparent diffusion coefficient |

| CA-125 | cancer antigen 125 |

| HPF | high-power field |

References

- Petousis, S.; Croce, S.; Kind, M.; Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Babin, G.; Lalet, C.; Querleu, D.; Floquet, A.; Pulido, M.; Guyon, F. BIOPSAR study: Ultrasound-guided pre-operative biopsy to assess histology of sarcoma-suspicious uterine tumors: A new study protocol. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Saha, R. Vaginal Leiomyoma: A Case Report. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2021, 59, 504–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffone, A.; Raimondo, D.; Neola, D.; Travaglino, A.; Raspollini, A.; Giorgi, M.; Santoro, A.; De Meis, L.; Zannoni, G.F.; Seracchioli, R.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Uterine Leiomyomas and Sarcomas. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2024, 31, 28–36.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żak, K.; Zaremba, B.; Rajtak, A.; Kotarski, J.; Amant, F.; Bobiński, M. Preoperative Differentiation of Uterine Leiomyomas and Leiomyosarcomas: Current Possibilities and Future Directions. Cancers 2022, 14, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Bonaffini, P.A.; Nougaret, S.; Fournier, L.; Dohan, A.; Chong, J.; Smith, J.; Addley, H.; Reinhold, C. How to differentiate uterine leiomyosarcoma from leiomyoma with imaging. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2019, 100, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, R.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Chen, K.; Tseng, S.C.; Wang, C.J.; Chao, A.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, G. Uterine fibroid-like tumors: Spectrum of MR imaging findings and their differential diagnosis. Abdom. Radiol. 2022, 47, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Mukuda, N.; Ochiai, R.; Yunaga, H.; Murakami, A.; Gonda, T.; Kishimoto, M.; Yamaji, D.; Ishibashi, M. MR imaging findings of unusual leiomyoma and malignant uterine myometrial tumors: What the radiologist should know. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2021, 39, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélage, S.; Laponche, C.; Homps, M.; Buy, J.N.; Just, P.A.; Jacob, D.; Ghossain, M.; Dion, É. Focal Area of Low T2 Signal on MRI Scans in a Heterogeneous Uterine Leiomyoma Does Not Exclude the Possibility of Malignancy: A Report of Two Cases. Radiol. Case Rep. 2025, 2025, 5388015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait Benkaddour, Y.; El Farji, A.; Soummani, A. Endometriosis of the vesico-vaginal septum: A rare and unusual localization (case report). BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Aoki, M.; Miyagawa, C.; Murakami, K.; Takaya, H.; Kotani, Y.; Nakai, H.; Matsumura, N. Differential Diagnosis of Uterine Leiomyoma and Uterine Sarcoma Using Magnetic Resonance Images: A Literature Review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, A.; Langer, R.; Bukovsky, I.; Caspi, E. Congenital anomalies of the müllerian system. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 51, 747–755, Erratum in: Fertil. Steril. 1994, 62, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Wahab, C.; Jannot, A.S.; Bonaffini, P.A.; Bourillon, C.; Cornou, C.; Lefrère-Belda, M.A.; Bats, A.S.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Bellucci, A.; Reinhold, C.; et al. Diagnostic Algorithm to Differentiate Benign Atypical Leiomyomas from Malignant Uterine Sarcomas with Diffusion-weighted MRI. Radiology 2020, 297, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbe, T.O.; Kobenge, F.M.; Metogo, J.A.M.; Manka’a Wankie, E.; Tolefac, P.N.; Belley-Priso, E. Vaginal leiomyoma: Medical imaging and diagnosis in a resource low tertiary hospital: Case report. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Kumari, S. A Rare Case of Vaginal Leiomyoma: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e76643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Ohashi, I.; Shibuya, H.; Tanabe, F.; Akashi, T. MR imaging of an atypical vaginal leiomyoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 178, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, D.M.; Cheung, W.; Gorelick, C.; Lee, Y.C.; Serur, E.; Zinn, H.L.; Sokolovski, M.; Abulafia, O. Sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings of an isolated vaginal leiomyoma. J. Ultrasound Med. 2007, 26, 1453–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesti, F.; La Marca, L.; Pietropolli, A.; Piccione, E. Multiple leiomyomas of the vagina in a premenopausal woman. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2004, 270, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, A.M.; Brody, J.M.; Curhan, R.P. Vaginal leiomyoma. A case report with imaging findings. J. Reprod. Med. 1996, 41, 875–877. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Yao, J. Vaginal leiomyoma: A case report. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 5–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Li, D.; Chen, S.L.; Zuo, N.; Sun, T.S.; Yang, Q. An effective method using laparoscopy in treatment of upper vaginal leiomyoma. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepika Goyal, S.; Garg, P.; Kanwat, J.; Kaur, N. Vaginal leiomyoma in a perimenopausal woman: A rare case report and review of the literature. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 2161–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Yadav, P.; Kaur, H. Vaginal Leiomyoma: A Rare Presentation. J. South Asian Feder. Obs. Gynaecol. 2014, 6, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H.M.; Rashid, R.J.; Othman, S.; Ahmed, N.H.A.; Ali, R.M.; Abdullah, A.M.; Yasseen, H.A.; Abdullah, F.; Kakamad, F.H. Vaginal leiomyoma: A case report. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 58, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjelloun, A.T.; Ziad, I.; Elkaroini, D.; Boufettal, H.; Mahdaoui, S.; Samouh, N. Vaginal leiomyoma mimicking a Cystocele (report case). Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 93, 106955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Sheng, X.; Kong, L.; Qi, J. Misdiagnosed Vaginal Leiomyoma: Case Report. Urol. Case Rep. 2015, 3, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chakrabarti, I.; De, A.; Pati, S. Vaginal leiomyoma. J. Midlife Health 2011, 2, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ye, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, T.; Ren, W. Transvaginal sonographic features of perineal masses in the female lower urogenital tract: A retrospective study of 71 patients. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 43, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckhardt, S.; Rolston, R.; Palmer, S.; Özel, B. Vaginal Angiomyofibroblastoma: A Case Report and Review of Diagnostic Imaging. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 2018, 7397121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, G.R.; Robboy, S.J.; Kurita, T.; Isaacson, D.; Shen, J.; Cao, M.; Baskin, L.S. Development of the human female reproductive tract. Differentiation 2018, 103, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Petousis, S.; Almperis, A.; Margioula-Siarkou, G.; Laganà, A.S.; Kourti, M.; Papanikolaou, A.; Dinas, K. Sarcoma Botryoides: Optimal Therapeutic Management and Prognosis of an Unfavorable Malignant Neoplasm of Female Children. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktürk, Ş.; Göktürk, Y.; Kamaşak, K.; Tekelioğlu, F. Rapidly Growing Leiomyoma Mimicking Schwannoma of the Saphenous Nerve in the Lower Extremity: An Unusual Case Report. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2024, 24, 325–329. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.C.; Mortimer, R.; Cooke, I.D. Myomectomy: A retrospective study to examine reproductive performance before and after surgery. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Y.; Ling, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H. Common and uncommon lesions of the vulva and vagina on magnetic resonance imaging: Correlations with pathological findings. BJR|Open 2023, 5, 20230002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, S.; Ninkova, R.V.; Russo, L.; Ponsiglione, A.; Gui, B.; Demundo, D.; Imbriaco, M.; Venkatesan, A.M.; Sala, E.; Nougaret, S.; et al. Incidental findings in female pelvis MRI performed for gynaecological malignancies. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, V.V.; Solanki, S.B.; Aggarwal, R.; Shah, K.; Kavyashri, H.C.; Anusha, M. Rare Vaginal Leiomyoma with Rare Microscopic Findings. Open Access J. Gynecol. 2022, 7, 000244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aşıcıoğlu, O.; Besimoglu, B.; Ateş, S. Comparison of transvaginal or transumbilical tissue extraction at laparoscopic gynecologic surgery: A 12-year experience. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 170, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnosis | Typical Age (Years) | MRI Features | Histopathology | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leiomyoma | All ages (peak 35–50) | T2-hypointense, homogeneous, well-circumscribed | Bland smooth muscle cells, <5 mitoses/10 HPF | Conservative enucleation |

| Embryonal RMS | <25 | T2-heterogeneous, myxoid areas | Small round blue cells, high mitotic activity | Multimodal therapy |

| Leiomyosarcoma | >40 (rare < 25) | Heterogeneous, necrosis, irregular margins | Nuclear atypia, >10 mitoses/10 HPF | Wide excision with margins |

| Aggressive Angiomyxoma | 20–40 | T2-hyperintense, swirled pattern, infiltrative | Myxoid stroma, scattered vessels | Wide excision |

| Authors, Year | Age | Size (mm) | Location | Symptoms | Imaging Findings | Histopathology | Treatment | Follow-Up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egbe et al., 2020 [13] | 36 | 102.7 × 175.8 mm | Posterior fornix | Dysuria, dyspareunia, cessation of sexual intercourse, discharge, sensation of mass | US: 60 mm × 40 mm hypoechogenic tumor in the upper part of the vagina and pelvis; MRI: vaginal tumor bulging through the posterior fornix and pushing up the pouch of Douglas and compressing the bladder and rectum | Leiomyoma | Transvaginally by sharp and blunt dissection | - | No mention |

| Ray and Kumari, 2024 [14] | 28 | 60 × 45 | Anterior vaginal wall | Vaginal discharge, excessive vaginal bleeding, retention of urine, sensation of mass | US: a mass was seen in the vagina measuring 5.8×4.2 cm The uterus and ovaries were normal in size and echo pattern with mild endometrial collection MRI: a well-defined solitary, homogeneous lesion of 6 × 6.7 × 5.4 cm arising from the anterior wall of the vagina | Benign leiomyoma of the vagina | Vaginal enucleation | - | No mention |

| Chakrabarti I et al., 2011 [26] | 38 | 60 × 40 | Upper vaginal wall | Lower abdominal pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia | US: hypoechoic mass in the upper part of vagina; MRI: no MRI was performed | Leiomyoma | Transvaginal enucleation | - | No mention |

| Shah M et al., 2021 [2] | 48 | 40 × 20 | Right vaginal wall | No complaint | Clinical examination only | Smooth muscles arranged in intersecting bundles and fascicles without atypia, mitosis, and necrosis | Transvaginal excision | 7 days | Full recovery |

| Shimada K et al., 2002 [15] | 37 | 22 | Posterior vaginal wall | No symptoms | MRI: homogeneous low signal intensity on the T1-weighted images and a homogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images | Benign leiomyoma, spindle-shaped cells | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Sherer DM et al., 2007 [16] | 47 | 35 | Lower anterior vaginal wall | No symptoms | US: heterogeneous mass measuring 3.5 cm adjacent to the urinary bladder | Typical leiomyoma features | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Sesti F et al., 2003 [17] | 32 | 33 × 35 | Lower-medium left lateral wall of the vagina | Dyspareunia and vaginal pain | US: spherical smooth-walled mass | Interlacing fascicles, no mitoses | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Ruggieri AM et al., 1996 [18] | 42 | 45 | Vesicovaginal septum | Pelvic pressure, constipation | MRI: a homogeneous lesion with a signal similar to that of the myometrium | Benign vaginal leiomyoma | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Gao, Y. et al., 2022 [19] | 48 | 65 × 46 | Anterior vaginal wall | Vaginal bleeding and a prolapsed hard vaginal mass | MRI: isointense on T1-weighted imaging, iso- to hypointense on T2-weighted imaging and slightly hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging | The samples were positive for desmin and smooth muscle actin, and negative for CD34-benign leiomyoma | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Zhang NN et al., 2020 [20] | 34 | 50 | Upper vaginal wall | Dyspareunia | US: hypoechoic nodule | Classic leiomyoma | Laparoscopic excision | 20 months | Pregnant after 20 months |

| Deepika et al., 2024 [21] | 50 | 50 × 60 | Anterior vaginal wall | Abnormal uterine bleeding, and heaviness in abdomen with mass protrusion outside introitus | US: a suspected mass protruding through the posterior bladder or anterior vaginal wall MRI: large polypoidal mass lesion is seen within the vaginal cavity two asymmetrical round ends with close proximity to bladder and urethra with pedunculated submucosal uterine fibroid with adenomyotic changes | Smooth muscle | Transvaginal enucleation | - | Symptom resolution |

| Singh R et al., 2014 [22] | 40 | 60 | Anterior vaginal wall | Smelling blood stained discharge from vagina | US: A well-defined smoothly marginated solid soft tissue mass was seen in the region of anterior fornix, MRI performed | dense fibrocollagenous tissue with inflammatory granulation | Abdominal enucleation | - | Not reported |

| Huda Muhaddien Muhammad et al., 2023 [23] | 48 | 37 × 36 | Anterior vaginal wall | Sensation of a mass | US: an enlarged anteverted uterus with an endometrial thickness of 14 mm and an endometrial polyp of 15 × 7 mm arising from the left upper anterolateral wall MRI: a well-defined, fusiform, submucosal vaginal mass originating from the anterior vaginal wall, measuring 37× 22 × 36 mm | Leiomyoma conventional | Transvaginal excision | - | Not reported |

| Ahmed Touimi Benjelloun et al. [24] | 65 | 30 | Anterior vaginal wall | Sensation of intravaginal ball, pelvic heaviness and dyspareunia | US: no abnormality MRI: rounded formation of the anterior wall of the vagina lateralized to the right measuring 3 cm in diameter with regular contours | Degenerated leiomyoma | Vaginal approach | 2 months | Complete recovery |

| Yu Wu et al., 2015 [25] | 44 | 30 × 30 | Anterior vaginal wall | Discomfort | MRI: a 30/30 mm mass which displaced the urethra laterally The mass showed a slightly heterogeneous low signal intensity on the T2-weighted images | Benign leiomyoma | Vaginal excision | - | - |

| Parameter | Literature Range (n = 14) | Present Case | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation | 22–58 years (mean: 39.2) | 20 years | Youngest reported |

| Tumor size | 3.2–17.6 cm (mean: 7.8) | 6.9 cm | Within 1 SD of mean |

| Symptom duration | 2–24 months (median: 10) | 12 months | Consistent with median |

| Time to diagnosis | 1–6 months | 2 months | Rapid diagnosis achieved |

| Surgical approach | 60% transvaginal | Transvaginal | Consistent with standard |

| Follow-up period | 6–60 months | 6 months | Minimum adequate follow-up |

| Recurrence rate | 0% (0/14) | 0% | Consistent with literature |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bucuri, C.E.; Ciortea, R.; Măluțan, A.M.; Oprea, A.V.; Roman, M.P.; Ormindean, C.M.; Nati, I.D.; Suciu, V.E.; Hăprean, A.E.; Mihu, D. Vesicovaginal Leiomyoma at 20 Years of Age—A Rare Clinical Entity: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212686

Bucuri CE, Ciortea R, Măluțan AM, Oprea AV, Roman MP, Ormindean CM, Nati ID, Suciu VE, Hăprean AE, Mihu D. Vesicovaginal Leiomyoma at 20 Years of Age—A Rare Clinical Entity: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(21):2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212686

Chicago/Turabian StyleBucuri, Carmen Elena, Răzvan Ciortea, Andrei Mihai Măluțan, Aron Valentin Oprea, Maria Patricia Roman, Cristina Mihaela Ormindean, Ionel Daniel Nati, Viorela Elena Suciu, Alex Emil Hăprean, and Dan Mihu. 2025. "Vesicovaginal Leiomyoma at 20 Years of Age—A Rare Clinical Entity: Case Report and Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 21: 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212686

APA StyleBucuri, C. E., Ciortea, R., Măluțan, A. M., Oprea, A. V., Roman, M. P., Ormindean, C. M., Nati, I. D., Suciu, V. E., Hăprean, A. E., & Mihu, D. (2025). Vesicovaginal Leiomyoma at 20 Years of Age—A Rare Clinical Entity: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(21), 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212686