Large Emphysematous Bulla After IQOS Use: A Case-Based Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

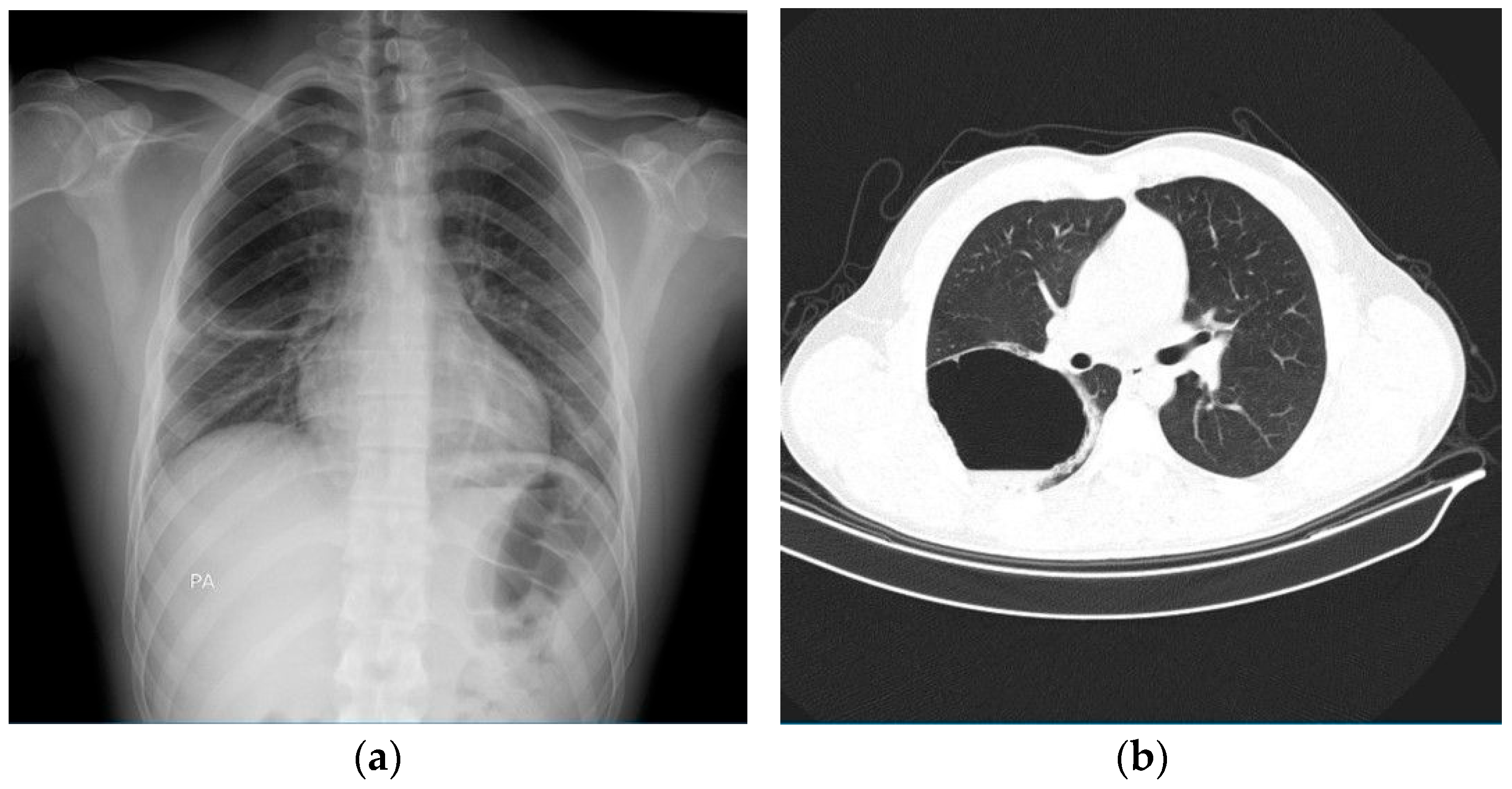

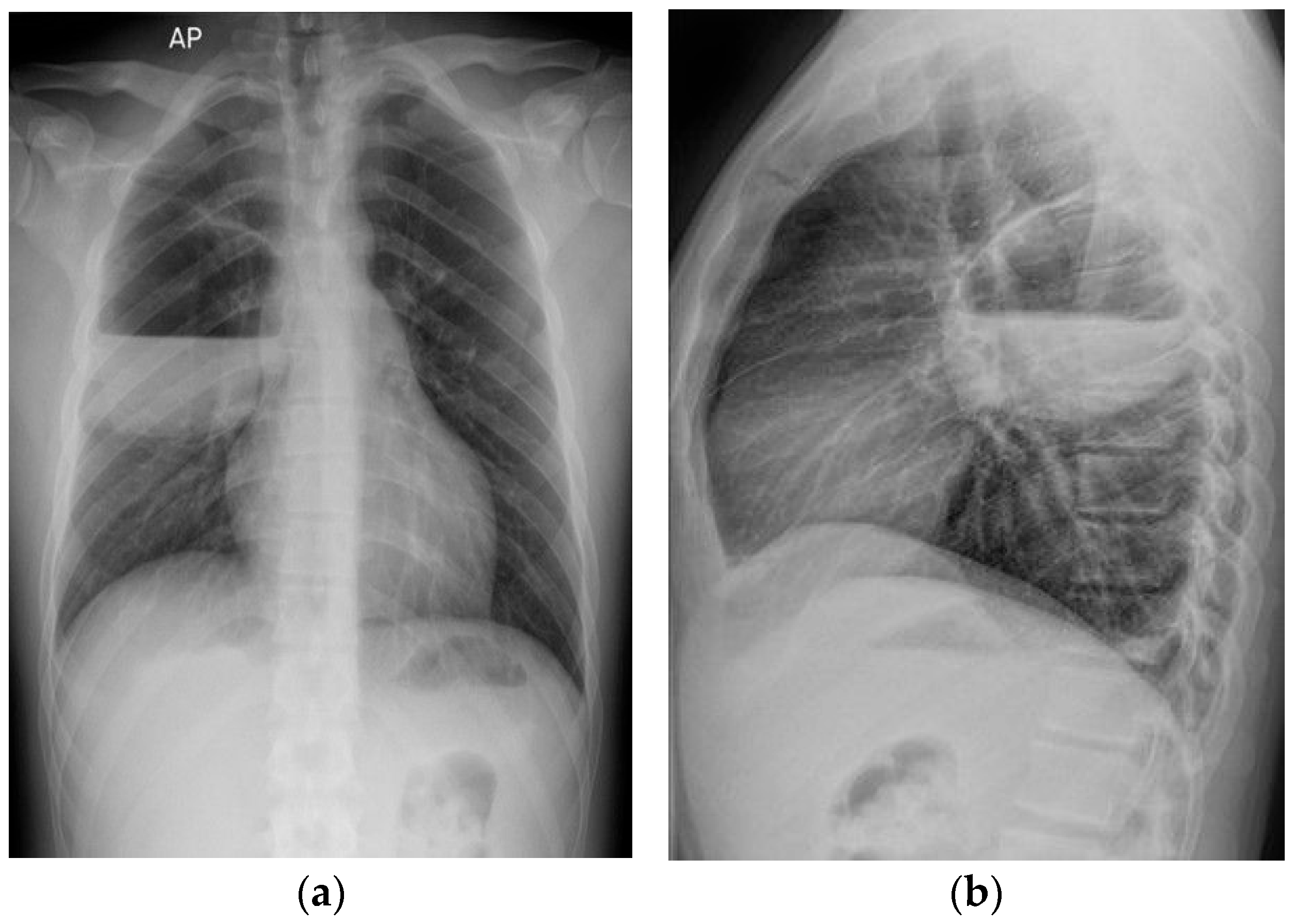

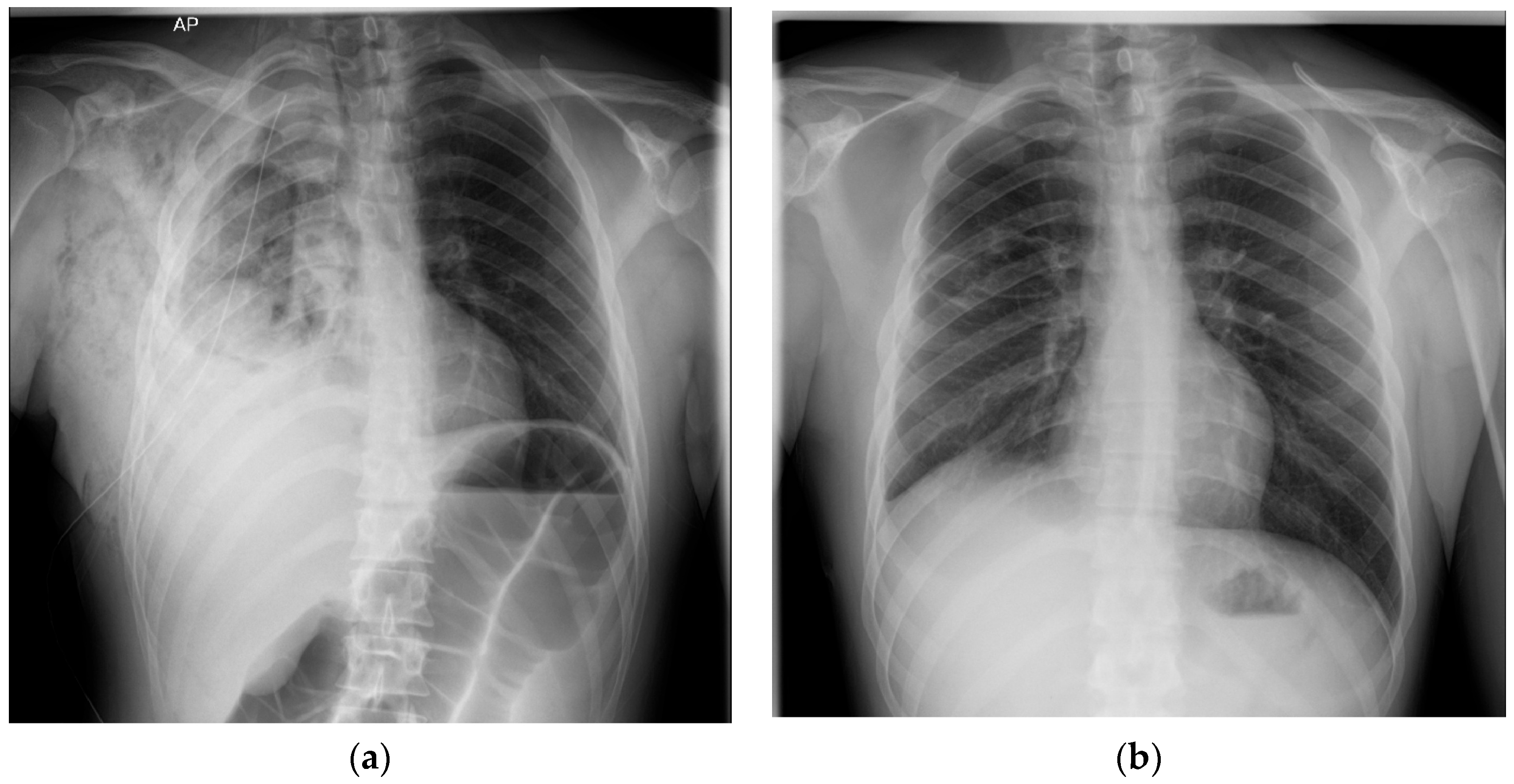

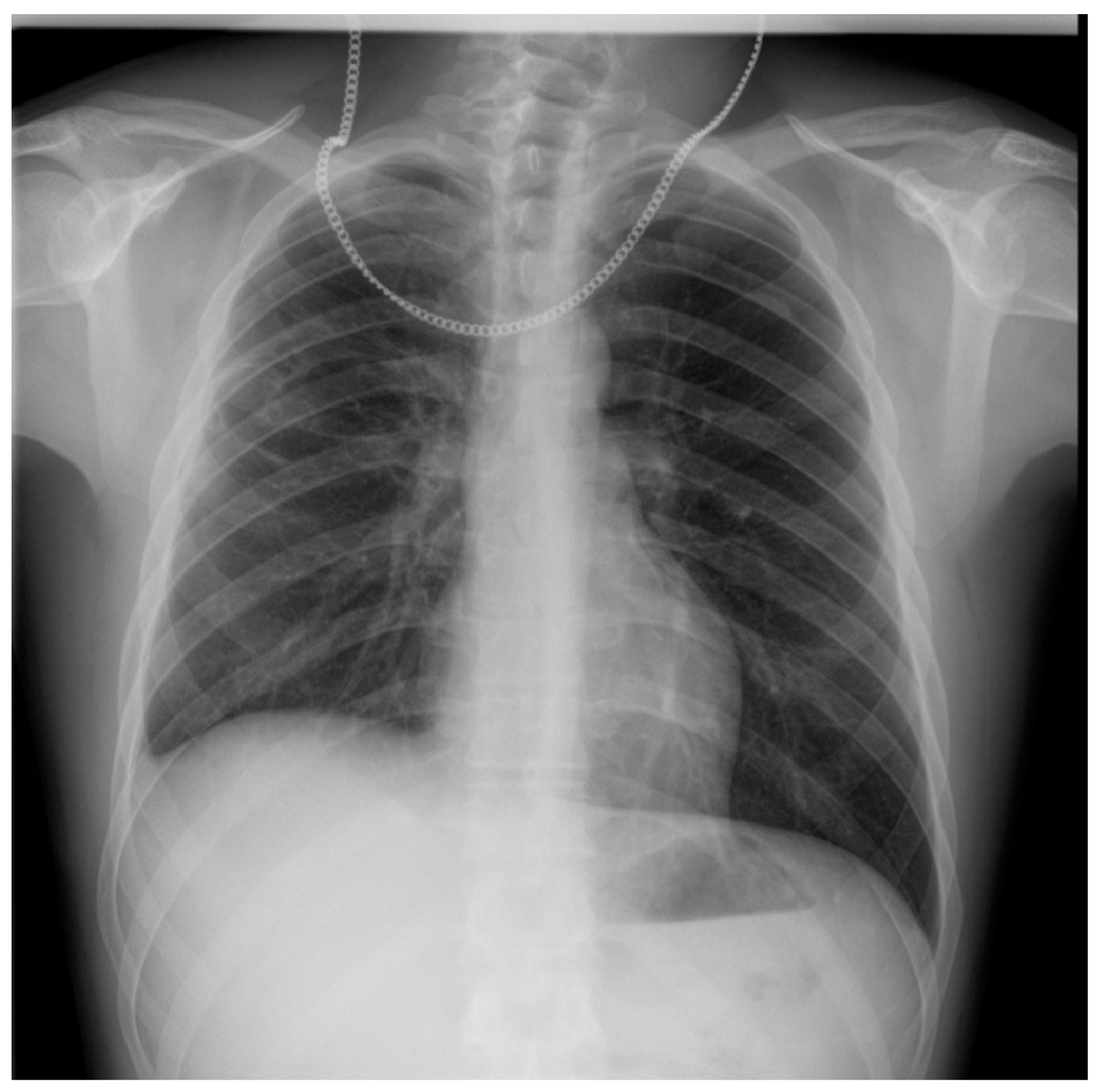

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HTPs | Heated Tobacco Products |

| Rx | Radiography |

| CT | Computer Tomography |

| IL | Interleukin |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| NA | Not Available |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| VATS | Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery |

References

- Ghazi, S.; Song, M.-A.; El-Hellani, A. A Scoping Review of the Toxicity and Health Impact of IQOS. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2024, 22, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munakata, S.; Ishimori, K.; Kitamura, N.; Ishikawa, S.; Takanami, Y.; Ito, S. Oxidative Stress Responses in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells Exposed to Cigarette Smoke and Vapor from Tobacco- and Nicotine-Containing Products. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 99, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto-Kusunose, S.; Sawa, M.; Inaba, Y.; Ushiyama, A.; Ishii, K.; Hattori, K.; Ogasawara, Y. Exposure to Aerosol Extract from Heated Tobacco Products Causes a Drastic Decrease of Glutathione and Protein Carbonylation in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 589, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, R.; Concha-Lozano, N.; Jacot-Sadowski, I.; Cornuz, J.; Berthet, A. Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Cigarettes: Smoke by Any Other Name. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1050–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, N.J.; Tran, P.L.; O’Connor, R.J.; Goniewicz, M.L. Cytotoxic Effects of Heated Tobacco Products (HTP) on Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Tob. Control 2018, 27, s26–s29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielan Darcy, M.; Mathew Suji, E.; Lu, W.; Sharma, P.; Sukhwinder Singh, S. The Ill Effects of IQOS on Airway Cells: Let’s Not Get Burned All over Again. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 63, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Jain, S.; Mukherjee, I.; Panda, S.R.; Zeki, A.A.; Naidu, V.; Sharma, P. The Effects of Dual IQOS and Cigarette Smoke Exposure on Airway Epithelial Cells: Implications for Lung Health and Respiratory Disease Pathogenesis. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9, 00558-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Gong, D.; Wang, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhang, J.; Hu, S.; Min, L. Chronic Exposure to IQOS Results in Impaired Pulmonary Function and Lung Tissue Damage in Mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2023, 374, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitta, N.A.; Sato, T.; Komura, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Mitsui, A.; Kuwasaki, E.; Takahashi, F.; Kodama, Y.; Seyama, K.; et al. Exposure to the Heated Tobacco Product IQOS Generates Apoptosis-Mediated Pulmonary Emphysema in Murine Lungs. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2022, 322, L699–L711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal, S.S.; Eapen, M.S.; Naidu, V.G.M.; Sharma, P. IQOS Exposure Impairs Human Airway Cell Homeostasis: Direct Comparison with Traditional Cigarette and E-Cigarette. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00159-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayin Gülensoy, E.; Yüksel, A.; Ogan, N.; Umudum, H.; Akpinar, E. Subacute Lung Injury Associated with Heated Tobacco Products. Düzce Tıp Fakültesi Derg. 2021, 23, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aokage, T.; Tsukahara, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Tokioka, F.; Taniguchi, A.; Naito, H.; Nakao, A. Heat-Not-Burn Cigarettes Induce Fulminant Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia Requiring Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 26, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.H.; Lee, D.H.; Roh, M.S.; Um, S.-J.; Kim, I. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia after Combined Use of Conventional and Heat-Not-Burn Cigarettes: A Case Report. Medicina 2022, 58, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Tomioka, H. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia Following Heat-Not-Burn Cigarette Smoking. Respirol. Case Rep. 2016, 4, e00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri, T.; Wada, C.; Ohkubo, H.; Takeda, N.; Fukumitsu, K.; Fukuda, S.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Uemura, T.; Takemura, M.; Maeno, K.; et al. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia Induced by Switching from Conventional Cigarette Smoking to Heated Tobacco Product Smoking. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 2911–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Hameed, M.; Alhafad, S.; Irfan Ul, H. Heated Tobacco Product (IQOS) Induced Pulmonary Infiltrates. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2024, 49, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, N.A.; Nookala, V. Bullous Emphysema. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537243/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Ralhan, T.; Padda, I.; Sethi, Y.; Karroum, P.; Fabian, D.; Hashmi, R.; Elmeligy, M.; Piccione, G.; Sharp, R.; Fulton, M. Unusual Case of Bullous Emphysema with Superimposed Pneumonia. Radiol. Case Rep. 2024, 19, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudabous, S.; Bouacida, I.; Ben Hadj Yahia, M.; Zribi, H.; Marghli, A. Surgical management of infected emphysema bulla: A case series. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2025, 126, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, O.R. The Challenge of Pulmonary Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infection: How to Bridge Research and Clinical Pathology. In Viral, Parasitic, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections; Debasis Bagchi, D., Das, A., Downs, B.W., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.A.; Kalathil, S.G.; Leigh, N.J.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Thanavala, Y.M. Can Switching from Cigarettes to Heated Tobacco Products Reduce Consequences of Pulmonary Infection? Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, D.; Rose, S.R.; Carter, R.B.; Musher, D.M.; Hamill, R.J. Fluid-containing emphysematous bullae: A spectrum of illness. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 32, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Patient | Symptoms | Chest X-Ray | Chest CT | BAL/Tracheal Secretions | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gulensoy et al. [11] | 56-year-old male who smoked 25 pack years and quit. He had been using IQOS for 2.5 years | Sudden chest pain and shortness of breath | NA | Pleural-based atelectasis and fibroatelectatic changes in the lower lobe of the right lung, fibroatelectatic changes in the left lung and pleural thickening | NA | Partial decortication and wedge resection was performed with video-assisted thoracic surgery. |

| Aokage et al. [12] | 16-year-old man who commenced smoking HTPs two weeks before admission | Shortness of breath that gradually worsened, with respiratory failure. | Ground-glass appearance | Mosaic ground-glass shadows on the distal sides of both lungs | Eosinophils 14.7%, neutrophils 51.7%, lymphocytes 33.6% | Methylprednisolone for 3 days and veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for 4 days. |

| Kang et al. [13] | 22-year-old female who started smoking HTPs 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms | Dyspnea, cough and fever | Bilateral patches of pulmonary infiltration | Bilateral multifocal patchy consolidations with multiple small nodular ground-glass opacities and interlobular septal thickening | 62% eosinophils in BAL, 15% lymphocytes, 14% macrophages, 4% neutrophils | Methylprednisolone |

| Kamada et al. [14] | 20-year-old man who started smoking HTPs 6 months previously | Fever and shortness of breath | Bilateral opacities | Bilateral infiltration, smooth interlobular septal thickening and pleural effusion | BAL with 60% eosinophils, 20% lymphocytes, 15% macrophages, 5% neutrophils | Prednisolone |

| Tajiri et al. [15] | 47-year-old woman who smoked for 27 years and switched from conventional cigarettes to smoking HTPs 4 months before the referral | Cough and fever | Bilateral infiltrate | Bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening | 72% eosinophils in BAL, 22% macrophages, 4% lymphocytes, 2% neutrophils | Prednisolone |

| Thomas et al. [16] | 40-year-old man who smoked for 20 years and switched from conventional cigarettes to smoking HTPs 6 months before the referral | No systemic complaints | Ill-defined nodular shadows in the right mid and lower zones. | Multiple scattered variable-sized nodules and patchy, partially solid opacities with surrounding ground glass opacification distributed sub-pleural and along the peri-bronchovascular region. Centrilobular emphysema bilaterally in the upper lobes, minimal pleural and pericardial fluid. | Bronchoscopy: 89% macrophages, 5% neutrophils, 4% lymphocytes, and 2% eosinophils. | Smoking cessation |

| Smoking | E-Cigarettes Marijuana Crack Cocaine |

| Infections | HIV Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia COVID-19 infection |

| Systemic diseases | Polyangiitis with granulomatosis Sarcoidosis |

| Genetic disorders | Sialic acid storage or Salla disease with impaired removal of sialic acid from lysosomes, causing cognitive impairment, ataxia, nystagmus, and basal and centriacinar emphysema Marfan syndrome Ehlers–Danlos type IV |

| Autoimmune disorders | Urticarial vasculitis syndrome with hypocomplementemia, a combination of urticaria, arthralgia, and angioedema, associated with panacinar emphysema Sjögren’s disease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corneanu, L.E.; Alupoae, D.D.; Creangă, Ș.V.; Catană, A.N.; Diaconu, A.-D.; Petris, O.R.; Șorodoc, L.; Lionte, C. Large Emphysematous Bulla After IQOS Use: A Case-Based Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172267

Corneanu LE, Alupoae DD, Creangă ȘV, Catană AN, Diaconu A-D, Petris OR, Șorodoc L, Lionte C. Large Emphysematous Bulla After IQOS Use: A Case-Based Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(17):2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172267

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorneanu, Luiza Elena, Diana Dumitrița Alupoae, Ștefan Valentin Creangă, Andreea Nicoleta Catană, Alexandra-Diana Diaconu, Ovidiu Rusalim Petris, Laurențiu Șorodoc, and Cătălina Lionte. 2025. "Large Emphysematous Bulla After IQOS Use: A Case-Based Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 17: 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172267

APA StyleCorneanu, L. E., Alupoae, D. D., Creangă, Ș. V., Catană, A. N., Diaconu, A.-D., Petris, O. R., Șorodoc, L., & Lionte, C. (2025). Large Emphysematous Bulla After IQOS Use: A Case-Based Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(17), 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172267