Lip Schwannoma—A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

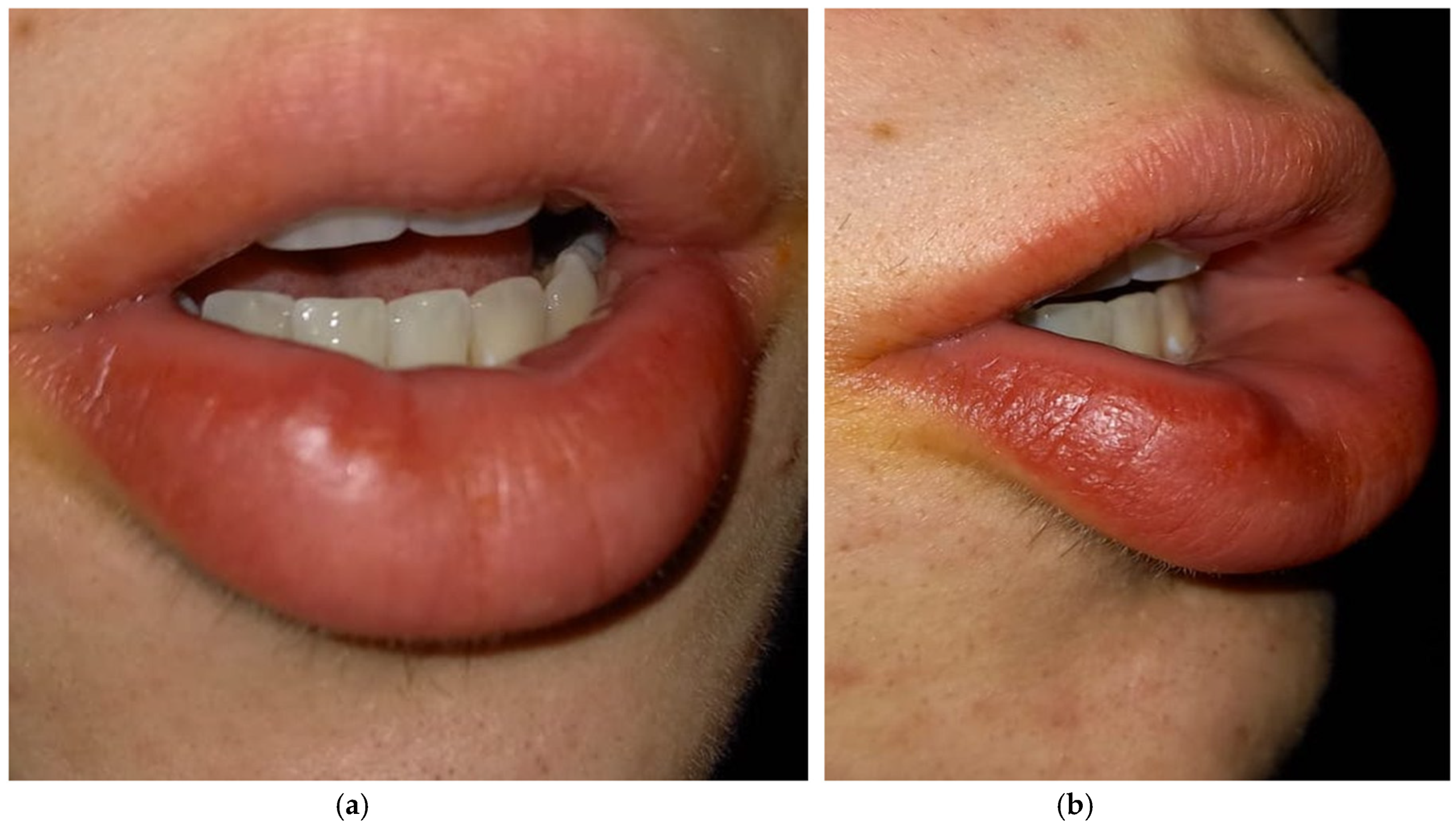

2. Case Presentation

3. Materials and Methods of the Review

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Generalitis

5.1.1. Definition

5.1.2. Epidemiology

5.1.3. Etiology

5.1.4. Clinical Features and Localization

5.1.5. Diagnosis

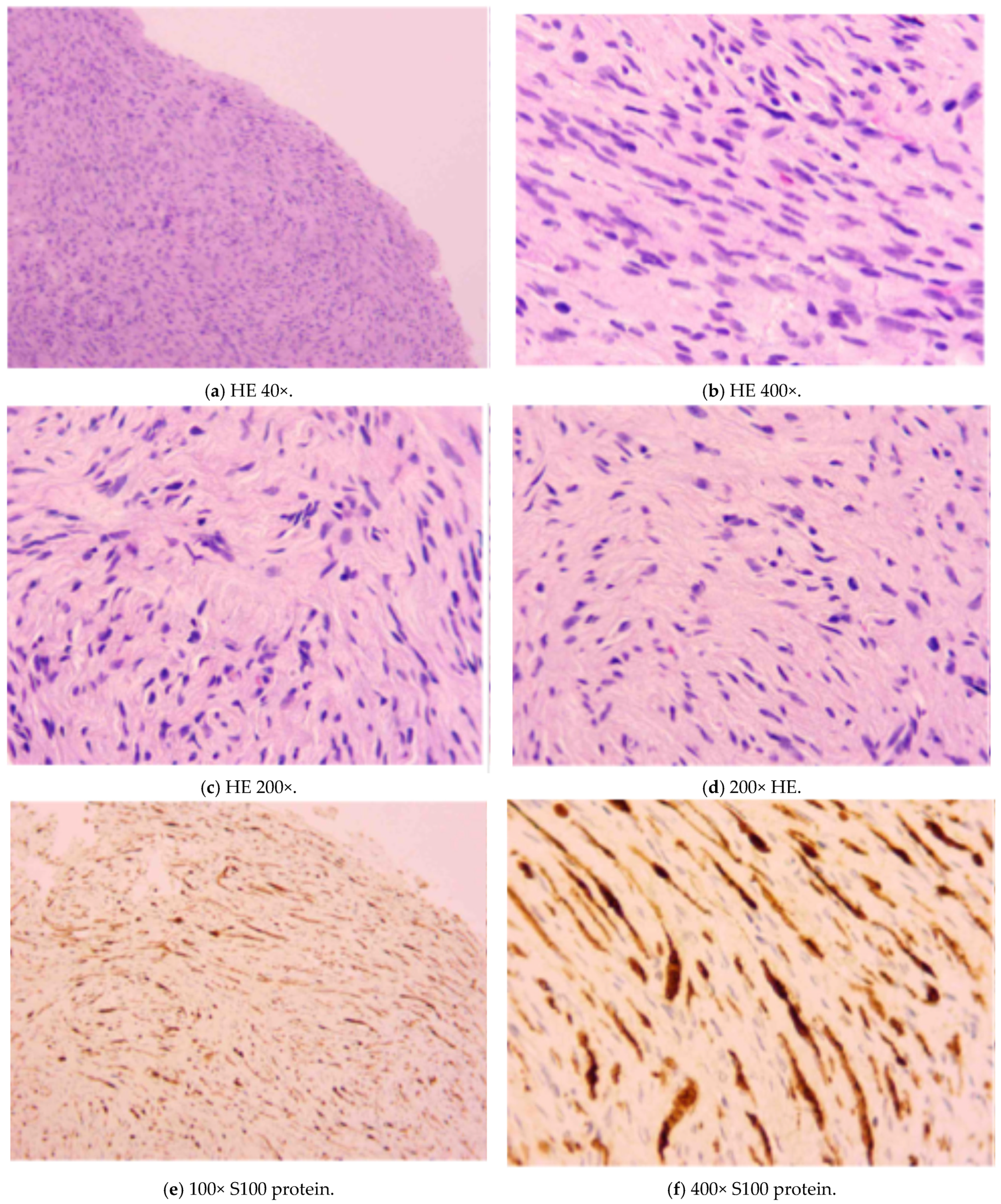

5.1.6. Histopathology

5.1.7. Treatment

5.1.8. Prognosis

5.1.9. Association with Systemic Diseases

5.2. Comparison Between Our Case Report and the Literature Review Data

5.3. Difference Between Pediatric and Adult Labial Schwannomas

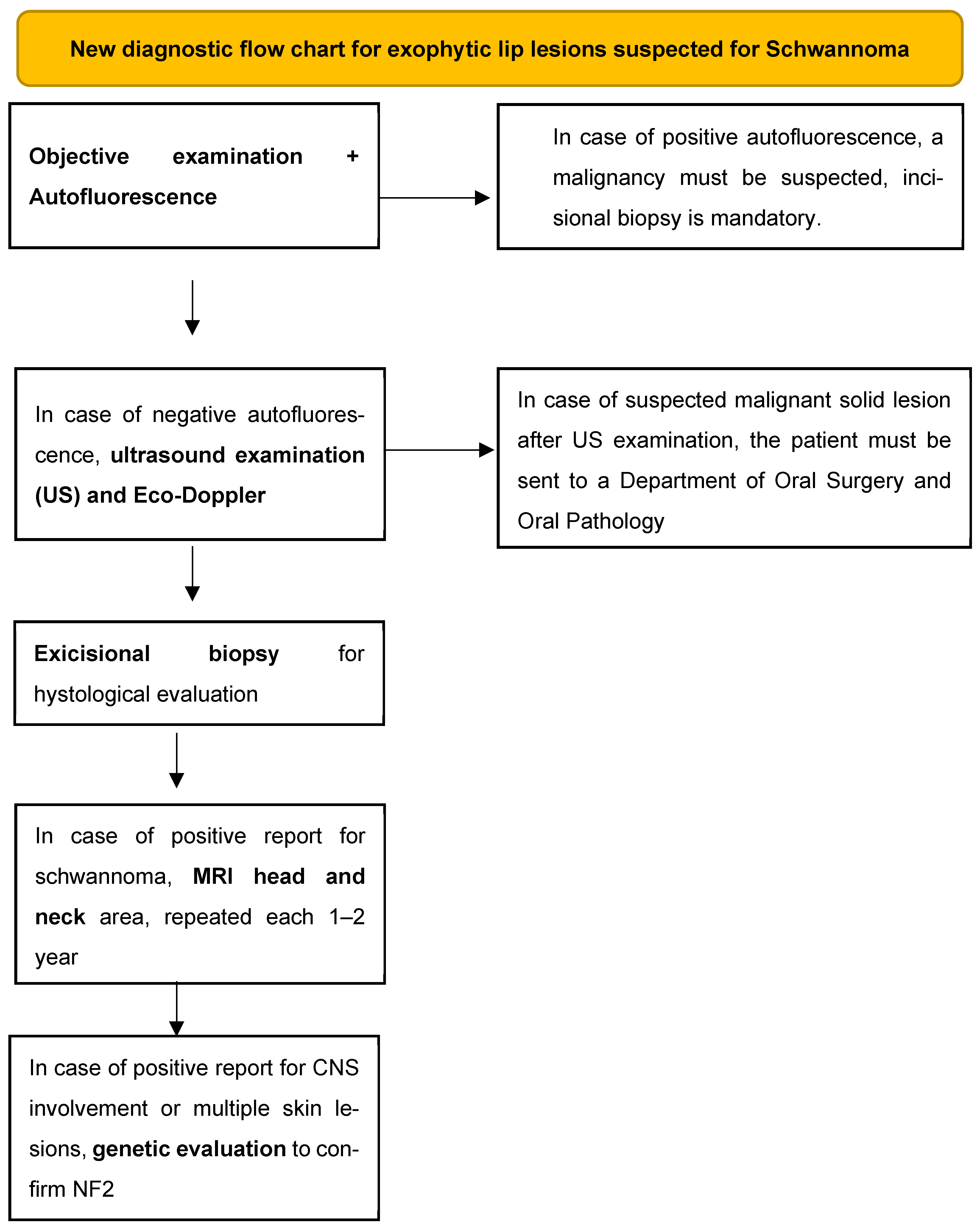

5.4. New Diagnostic Flow Chart Proposal

- (1)

- Objective examination that includes inspection and palpation of the tissues (a fluctuating consistency may point us towards a cystic lesion, while a tense–elastic consistency may point us towards a solid neoformation) and evaluation by autofluorescence to exclude solid malignant or potentially malignant lesions [28]. Dark-green or black color of the illuminated mucosa could be related to malignancies;

- (2)

- Perform an intraoral ultrasound examination with possible eco-Doppler to highlight the intra- and perilesional blood vessels and understand if the content of the lesion is liquid or solid;

- (3)

- Excisional biopsy for histological evaluation;

- (4)

- MRI of the head and neck area to be performed immediately after the possible histological confirmation and every 1–2 years as a follow-up to intercept any other neo-formations or lesions that affect nervous tissues;

- (5)

- Genetic investigation to evaluate any alterations of the nervous tissue and to discover the syndromic picture associated with the oral schwannoma.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Carriches, C.; Baca-Pérez-Bryan, R.; Montalvo-Montero, S. Schwannoma located in the palate: Clinical case and literature review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.D.; Anunciato De Jesus, L.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Bussadori, S.K.; Taghloubi, S.A.; Martins, M.A.T. Intra-oral schwannoma: Case report and literature review. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2009, 20, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassehi, Y.; Rashid, A.; Pitiyage, G.; Jayaram, R. Floor of mouth schwannoma mimicking a salivary gland neoplasm: A report of the case and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phulware, R.H.; Sardana, R.; Chauhan, D.S.; Ahuja, A.; Bhardwaj, M. Extracranial Schwannomas of the Head and Neck: A Literature Review and Audit of Diagnosed Cases Over a Period of Eight Years. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, J.; Sahabnasagh, Z.; Saghafi, S.; Sahebnasagh, Z.; Amiri, N. Intraoral ancient schwannoma: A systematic review of the case reports. Dent. Res. J. 2017, 14, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Q.; Xuan, Y. Maxillary gingival neurolemmoma: A case report and literature review. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Santiago, N.; Patel, K. Review of Pediatric Head and Neck Neoplasms that Raise the Possibility of a Cancer Predisposition Syndrome. Head Neck Pathol. 2021, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, M.; Praticò, A.D.; Serra, A.; Maiolino, L.; Cocuzza, S.; Di Mauro, P.; Licciardello, L.; Milone, P.; Privitera, G.; Belfiore, G.; et al. Childhood neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and related disorders: From bench to bedside and biologically targeted therapies. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2016, 36, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachir, S.; Shah, S.; Shapiro, S.; Koehler, A.; Mahammedi, A.; Samy, R.N.; Zuccarello, M.; Schorry, E.; Sengupta, S. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and the implications for vestibular schwannoma and meningioma pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baderca, F.; Cojocaru, S.; Lazǎr, E.; Lǎzureanu, C.; Faur, A.; Lighezan, R.; Alexa, A.; Raica, M.; Vǎlean, M.; Balica, N. Schwannoma of the lip: Case report and review of the literature. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2008, 49, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Dokania, V.; Rajguru, A.; Mayashankar, V.; Mukherjee, I.; Jaipuria, B.; Shere, D. Palatal schwannoma: An analysis of 45 literature reports and of an illustrative case. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 23, E360–E370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.L.; Schulz, A.; Morrison, H. Pathomechanisms in schwannoma development and progression. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5421–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karajannis, M.A.; Ferner, R.E. Neurofibromatosis-related tumors: Emerging biology and therapies. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2015, 27, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Woo, T.G.; Kang, S.M.; Park, S.; Kim, M.; Park, B.J. NF2-Related Schwannomatosis (NF2): Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Avenues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pećina-Šlaus, N. Merlin, the NF2 gene product. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2013, 19, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitenga, J.L.; Aird, G.A.; Nguyen, A.; Vaudreuil, A.; Huerter, C. Clinical features and surgical treatment of schwannoma affecting the base of the tongue: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 21, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhashraj, K.; Balanand, S.; Pajaniammalle, S. Ancient schwannoma arising from mental nerve. A case report and review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, R. Current understanding of neurofibromatosis type 1, 2, and schwannomatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitenga, J.; Aird, G.; Vaudreuil, A.; Huerter, C.J. Clinical features and management of schwannoma affecting the upper and lower lips. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Rahul, S.K.; Kumar, B.; Hasan, Z.; Yadav, R.; Chaubey, D.; Prasad, R.; Keshri, R. Lingual schwannoma in a 4-year-old female baby. J. Indira Gandhi Inst. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, R.; Pahlevi, M.R.; Rosanto, Y.B.; Sejati, B.P.; Hasan, C.Y. A rare case of upper lip schwannoma: A case report with analysis of the histological, immunohistochemical and pathogenesis aspects. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 118, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayindir, T.; Kalcioglu, M.T.; Cicek, M.T.; Karadag, N.; Karaman, A. Schwannoma with an Uncommon Upper Lip Location and Literature Review. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2013, 2013, 363049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hajong, R.; Hajong, D.; Naku, N.; Sharma, G.; Boruah, M. Schwannoma of upper lip: Report of a rare case in a rare age group. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2016, 10, PD10–PD11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J. An unexpected and rare outcome of a common nodular mass on upper lip in a pediatric patient with a history of trauma–Schwannoma. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 10, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Menezes, B.N.F.; Cunha, J.L.S.; Chaves-Júnior, S.d.C.; Bezerra, B.T. Schwannoma of the lower lip mimicking a mucocele in children. Autops. Case Reports 2020, 10, e2019134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhammad, G.; Alsaad, A.; Aljohani, T.; Alajlan, A. Schwannoma of the Lower Lip: A Case Report of an Unusual Presentation. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2021, 13, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.T.; Chang, K.V.; Hsu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.C.; Hsu, P.C. Ultrasound Imaging for a Rare Cause of Sciatica: A Schwannoma of the Sciatic Nerve. Cureus 2020, 12, e8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lau, J.; O, G.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Balasubramaniam, R.; Frydrych, A.; Kujan, O. Adjunctive aids for the detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2024, 60, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

|

| Year | Author | Title | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | López-Carriches et al. | Schwannoma located in the palate: Clinical case and literature review | [1] |

| 2009 | Martins et al. | Intra-oral schwannoma: Case report and literature review | [2] |

| 2021 | Nassehi et al. | Floor of mouth schwannoma mimicking a salivary gland neoplasm: A report of the case and review of the literature | [3] |

| 2017 | Salehinejad et al. | Intraoral ancient schwannoma: A systematic review of the case reports | [5] |

| 2023 | Zhang et al. | Maxillary gingival neurolemmoma: a case report and literature review | [6] |

| 2008 | Baderca et al. | Schwannoma of the lip: Case report and review of the literature | [10] |

| 2019 | Dokania et al. | Palatal schwannoma: An analysis of 45 literature reports and of an illustrative case | [11] |

| 2009 | Subhashraj et al. | Ancient schwannoma arising from mental nerve. A case report and review. | [17] |

| 2021 | Thakur et al. | Lingual schwannoma in a 4-year-old female baby | [20] |

| 2024 | Maulana et al. | A rare case of upper lip schwannoma: A case report with analysis of the histological, immunohistochemical and pathogenesis aspects | [21] |

| 2013 | Bayindir et al. | Schwannoma with an Uncommon Upper Lip Location and Literature Review | [22] |

| 2016 | Hajong et al. | Schwannoma of upper lip: Report of a rare case in a rare age group | [23] |

| 2019 | Desai et al. | An unexpected and rare outcome of a common nodular mass on upper lip in a pediatric patient with a history of trauma–Schwannoma | [24] |

| 2020 | de Menezes et al. | Schwannoma of the lower lip mimicking a mucocele in children | [25] |

| 2021 | Alhammad et al. | Schwannoma of the lower lip mimicking a mucocele in children | [26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casu, C.; Pinna, M.; Butera, A.; Maiorani, C.; Campisi, G.; Gerosa, C.; Caiazzo, A.; Scribante, A.; Orrù, G. Lip Schwannoma—A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and a Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15141825

Casu C, Pinna M, Butera A, Maiorani C, Campisi G, Gerosa C, Caiazzo A, Scribante A, Orrù G. Lip Schwannoma—A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and a Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(14):1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15141825

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasu, Cinzia, Mara Pinna, Andrea Butera, Carolina Maiorani, Girolamo Campisi, Clara Gerosa, Antonella Caiazzo, Andrea Scribante, and Germano Orrù. 2025. "Lip Schwannoma—A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and a Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 14: 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15141825

APA StyleCasu, C., Pinna, M., Butera, A., Maiorani, C., Campisi, G., Gerosa, C., Caiazzo, A., Scribante, A., & Orrù, G. (2025). Lip Schwannoma—A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient: Case Report and a Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(14), 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15141825