Validation of Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infection Self-Testing Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

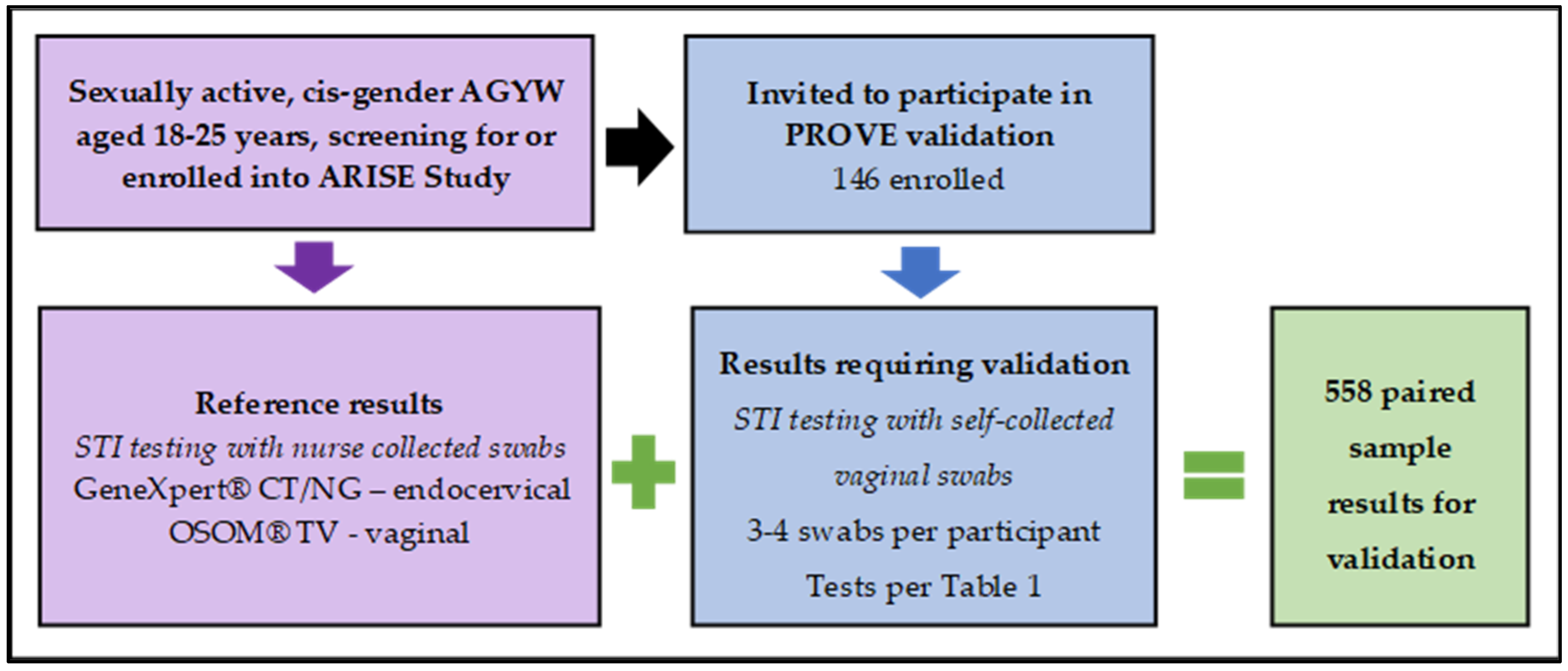

2.1. Initial Cross-Sectional Validation—PROVE Study

2.2. Longitudinal Cohort with Observed New STI Diagnoses and Visby Medical™ Sexual Health Test Validation—PALESA Study

2.3. Sample Self-Collection Procedures

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

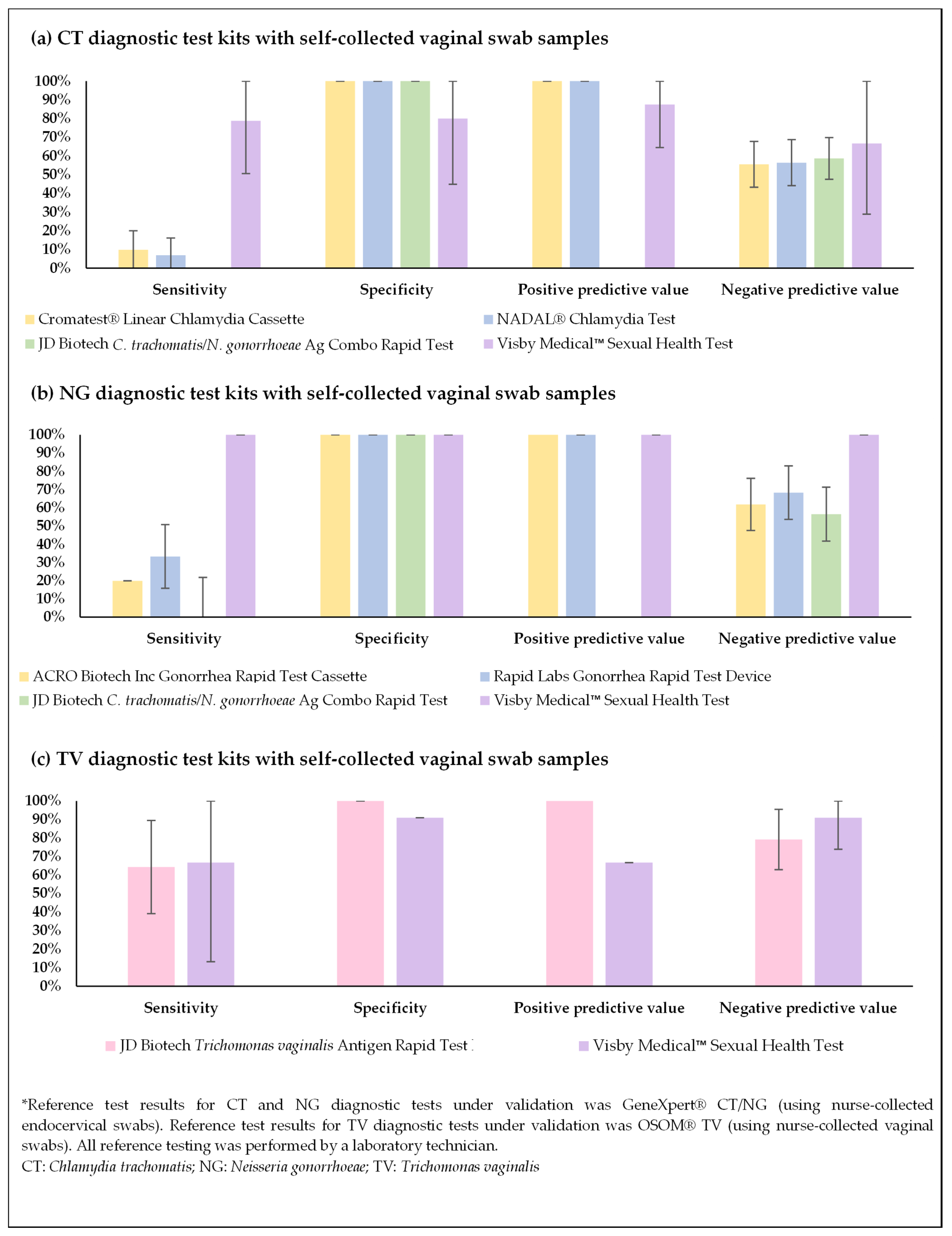

3.2. Initial Cross-Sectional Validation Results—PROVE Study

3.3. Longitudinal Cohort Results—PALESA Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGYW | Adolescent Girls and Young Women |

| ARISE | Acceptability Research on Integrated point-of-care STI testing and Expedited partner therapy |

| CRS | Clinical Research Site |

| CT | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CLIA | Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HREC | Human Research Ethics Committee |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| NAAT | Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests |

| NG | Neisseria gonorrhea |

| NPA | Negative Percent Agreement |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Values |

| PALESA | PrEP restart for Adolescent girls and young women using STI self-testing and Assessment of risk |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| POC | Point-of-Care |

| PPA | Positive Percent Agreement |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Values |

| PrEP | Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| PROVE | Point-of-care Rapid STI test Optimization and Validation Extension |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| SA NDoH | South African National Department of Health |

| SAHPRA | South African Health Products Regulatory Authority |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| STIs | Sexually Transmitted Infections |

| TV | Trichomonas vaginalis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Rowley, J.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Korenromp, E.; Low, N.; Unemo, M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chico, R.M.; Smolak, A.; Newman, L.; Gottlieb, S.; et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Kularatne, R.S.; Niit, R.; Rowley, J.; Kufa-Chakezha, T.; Peters, R.P.H.; Taylor, M.M.; Johnson, L.F.; Korenromp, E.L. Adult gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis prevalence, incidence, treatment and syndromic case reporting in South Africa: Estimates using the Spectrum-STI model, 1990–2017. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.; Kufa, T.; Dorrell, P.; Kularatne, R.; Maithufi, R.; Chidarikire, T.; Pillay, Y.; Mokgatle, M. Evaluation of the national clinical sentinel surveillance system for sexually transmitted infections in South Africa: Analysis of provincial and district-level data. S. Afr. Med. J. = Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd. 2023, 113, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Let Our Actions Count—South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. Available online: https://sanac.org.za//wp-content/uploads/2017/06/NSP_FullDocument_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Murewanhema, G.; Musuka, G.; Moyo, P.; Moyo, E.; Dzinamarira, T. HIV and adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for expedited action to reduce new infections. IJID Reg. 2022, 5, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkhize, P.; Mehou-Loko, C.; Maphumulo, N.; Radzey, N.; Abrahams, A.G.; Sibeko, S.; Harryparsad, R.; Manhanzva, M.; Meyer, B.; Radebe, P.; et al. Differences in HIV risk factors between South African adolescents and adult women and their association with sexually transmitted infections. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2025, 101, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, G.; Celum, C.; Szydlo, D.; Brown, E.R.; Akello, C.A.; Nakalega, R.; Macdonald, P.; Milan, G.; Palanee-Phillips, T.; Reddy, K.; et al. Adherence, safety, and choice of the monthly dapivirine vaginal ring or oral emtricitabine plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among African adolescent girls and young women: A randomised, open-label, crossover trial. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e779–e789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Mgodi, N.; Bekker, L.G.; Baeten, J.M.; Li, C.; Donnell, D.; Agyei, Y.; Lennon, D.; Rose, S.M.; Mokgatle, M.; et al. High prevalence and incidence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia in young women eligible for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in South Africa and Zimbabwe: Results from the HPTN 082 trial. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2023, 99, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, L.; Daniels, J.; Gebengu, A.; Mazzola, L.; Gleeson, B.; Blümel, B.; Piton, J.; Mdingi, M.; Gigi, R.M.S.; Ferreyra, C.; et al. Implementation considerations for a point-of-care Neisseria gonorrhoeae rapid diagnostic test at primary healthcare level in South Africa: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichomoniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trichomoniasis#:~:text=In%20females%2C%20trichomoniasis%20is%20a,prostatitis%20and%20decreased%20sperm%20motility (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Cohen, M.S. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: No longer a hypothesis. Lancet 1998, 351, S5–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for the Management of Symptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024168 (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Kaida, A.; Dietrich, J.J.; Laher, F.; Beksinska, M.; Jaggernath, M.; Bardsley, M.; Smith, P.; Cotton, L.; Chitneni, P.; Closson, K.; et al. A high burden of asymptomatic genital tract infections undermines the syndromic management approach among adolescents and young adults in South Africa: Implications for HIV prevention efforts. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, V.; Moodley, D.; Naidoo, M.; Connoly, C.; Ngcapu, S.; Abdool Karim, Q. High incidence of asymptomatic genital tract infections in pregnancy in adolescent girls and young women: Need for repeat aetiological screening. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2023, 99, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.; Bukusi, E.; Celum, C.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Baeten, J.M. Sexually transmitted infections among African women: An opportunity for combination sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevention. AIDS 2020, 34, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EclinicalMedicine. Antimicrobial resistance: A top ten global public health threat. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point-of-Care Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infections—Target Product Profiles. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/371294/9789240077102-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sadio, A.J.; Kouanfack, H.R.; Konu, R.Y.; Gbeasor-Komlanvi, F.A.; Azialey, G.K.; Gounon, H.K.; Tchankoni, M.K.; Amenyah-Ehlan, A.P.; Dagnra, A.C.; Ekouevi, D.K. HIV self-testing: A highly acceptable and feasible strategy for reconnecting street adolescents with HIV screening and prevention services in Togo (The STADOS study). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otiso, L.; Alhassan, Y.; Odhong, T.; Onyango, B.; Muturi, N.; Hemingway, C.; Murray, L.; Ogwang, E.; Okoth, L.; Oguche, M.; et al. Exploring acceptability, opportunities, and challenges of community-based home pregnancy testing for early antenatal care initiation in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzmann, J.; Hellriegel-Nehrkorn, A.; Dilas, M.; Pohl, R.; Hellmich, M.; Apfelbacher, C.J.; Kaasch, A.J. Determining the optimal frequency of SARS-CoV-2 regular asymptomatic testing: A randomized feasibility trial in a home care setting. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issue Brief: The Role of HIV Self-Testing in Ending the HIV Epidemic. Available online: https://bhocpartners.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/cdc-hiv-self-testing-issue-brief-dhp202262.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Kersh, E.N. Advances in Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing at Home and in Nonclinical Settings Close to the Home. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2022, 49, S12–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromatest Linear Chlamydia Cassette Package Insert. Available online: https://www.linear.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/4240220-Chlamydia-cassette-20t-ing.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- NADAL® Chlamydia Test Package Insert. Available online: https://fgmdiagnostici.it/files/76.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- JD Biotech C. trachomatis/N. gonorrhoeae Ag Combo Rapid Test. In Package Insert; JD Biotech: Jinan, China, 2022.

- Rapid Labs Gonorrhea Rapid Test Device (Swab). In Package Insert; Rapid Labs Ltd.: Colchester, UK, 2017.

- Acro Biotech Gonorrhea Rapid Test Cassette (Swab). In Package Insert; ACRO Biotech, Inc.: Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA, 2017.

- JD Biotech Trichomonas vaginalis Antigen Rapid Test Kit. In Package Insert; JD Biotech: Jinan, China, 2022.

- Visby Medical™ Sexual Health Test Instructions for Use. Available online: https://www.visbymedical.com/assets/sexual-health-test/Visby-Medical-Sexual-Health-Test-Instructions-for-Use.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Sexually Transmitted Infections Management Guidelines. 2018. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/sti-guidelines-27-08-19.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Visby Medical™ Sexual Health Quick Reference Guide. Available online: https://www.visbymedical.com/assets/sexual-health-test/Visby-Medical-Sexual-Health-Test-Quick-Reference-Guide.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Visby Medical™ Vaginal Specimen Collection Kit Self Collection Instructions. Available online: https://www.visbymedical.com/assets/sexual-health-test/Visby-Medical-Sexual-Health-Test-Vaginal-Specimen-Collection-Instructions.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigcu, N.; Reddy, K.; Howett, R.; Ndlovu, N.; Njobane, V.; Loeb, A.M.; Palanee-Phillips, T.; Balkus, J.E. Evaluation of a point-of-care PCR STI testing device among young women in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 2024 STI Prevention Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–19 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Trevethan, R. Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Values: Foundations, Pliabilities, and Pitfalls in Research and Practice. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA News Release: FDA Grants Marketing Authorization of First Home Test for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea and Trichomoniasis. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-marketing-authorization-first-home-test-chlamydia-gonorrhea-and-trichomoniasis?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Makoni, M. Power cuts and South Africa’s health care. Lancet 2023, 401, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhai, A. Climate change, extreme heat and heat waves. S. Afr. Med. J. = Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd. 2024, 114, e2804. [Google Scholar]

- Scorgie, F.; Kunene, B.; Smit, J.A.; Manzini, N.; Chersich, M.F.; Preston-Whyte, E.M. In search of sexual pleasure and fidelity: Vaginal practices in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Cult. Health Sex. 2009, 11, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test | Recommended Sample Type | Comparison Test | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical swab | PCR | 90.2% (76.9–96.5%) * | 96.0% (91.2–99.4%) * |

| Cervical swab | PCR | 90.2% (76.9–96.5%) * | 96.0% (91.2–99.4%) * |

| Urine/vaginal swab | Clinical diagnostics | CT 87% NG 93% | CT 88% NG 90% |

| Cervical swab | Culture | 94.4% (86.2–98.4%) * | 96.9% (91.3–99.4%) * |

| Cervical swab | Culture | 94.4% (86.2–98.4%) * | 96.9% (91.3–99.4%) * |

| Urine/vaginal swab | Speculum exams | 100% | 99% |

| Vaginal swab | NAAT | CT 97.4% (93.5–99.0%) * PPA NG 97.8% (88.4–99.6%) * PPA TV 99.3% (96.0–99.9%) * SN | CT 97.8% (96.9–98.4%) * NPA NG 99.1% (98.5–99.4%) * NPA TV 96.7% (95.8–97.5%) * SP |

| Demographic Characteristic | Participants for the Initial Cross-Sectional Validation (PROVE) * (n = 146) | Participants for the Longitudinal Cohort (PALESA) (n = 28) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Median (IQR) | 21 (19–23) | 18 (17–18) |

| Race, n (%) | Black | 141 (96.6%) | 28 (100%) |

| Mixed race | 1 (0.7%) | 0 | |

| Missing 1 | 4 (2.7%) | - | |

| Religion, n (%) | Agnostic or no religion | 8 (5.5%) | 5 (17.9%) |

| Christian | 119 (81.5%) | 23 (82.1%) | |

| Muslim | 1 (0.7%) | - | |

| Traditional African beliefs | 11 (7.5%) | - | |

| Other (Shembe, Sotho, Tsonga) | 3 (2.1%) | - | |

| Missing 1 | 4 (2.7%) | - | |

| Highest level of education achieved, n (%) | Secondary school, not complete | 33 (22.6%) | 20 (71.4%) |

| Secondary school, complete | 83 (56.8%) | 7 (25%) | |

| College or university, not complete | 20 (13.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| College or university, complete | 6 (4.1%) | 0 | |

| Not collected 2 | 4 (2.7%) | - | |

| Attending any form of school now, n (%) 2 | Yes | 51 (34.9%) | - |

| No | 91 (62.3%) | - | |

| Not collected 2 | 4 (2.7%) | - | |

| STI | Test Kit (Number of Samples) | True Pos | False Pos | True Neg | False Neg | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Kappa (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT * |

| 3 | 0 | 35 | 28 | 9.7% (0–20.1%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 55.6% (43.3–67.8%) | 0.10 (−0.01–0.21) | NA | 0.90 (0.80–1.01) |

| 2 | 0 | 35 | 27 | 6.9% (0–16.1%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 56.5% (44.1–68.8%) | 0.07 (−0.03–0.18) | NA | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | |

| 0 | 0 | 44 | 31 | 0% | 100% (100–100%) | NA | 58.7% (47.5–69.8%) | NA | NA | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | |

| 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 78.8% (50.6–100%) | 80.0% (44.9–100%) | 87.5% (64.6–100%) | 66.7% (28.9–100%) | 0.55 (0.11–0.99) | 3.89 (0.65–23.23) | 0.28 (0.08–1.02) | |

| NG * |

| 0 | 0 | 26 | 20 | 0% | 100% (100–100%) | NA | 56.5% (42.2–70.9%) | NA | NA | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| 4 | 0 | 26 | 16 | 20.0% (2.5–37.5%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 61.9% (47.2–76.6%) | 0.22 (0.03–0.41) | NA | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) | |

| 6 | 0 | 26 | 12 | 33.3% (11.6–55.1%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 68.4% (53.6–83.2%) | 0.37 (0.14–0.61) | NA | 0.67 (0.48–0.92) | |

| 5 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | NA | 0 | |

| TV * |

| 9 | 0 | 19 | 5 | 64.3% (39.2–89.4%) | 100% (100–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | 79.2% (62.9–95.4%) | 0.67 (0.43–0.92) | NA | 0.36 (0.18–0.72) |

| 2 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 66.7% (13.3–100%) | 90.9% (73.9–100%) | 66.7% (13.3–100%) | 90.9% (73.9–100%) | 0.58 (0.05–1.00) | 7.33 (0.96–56.00) | 0.37 (0.07–1.84) |

| STI | Positive Visby Medical™ Sexual Health Test | Positive GeneXpert® CT/NG | Positive GeneXpert® TV | Accuracy of Positive Visby Medical™ Sexual Health Test Results (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 9 | 8 | - | 100% (100–100%) |

| NG | 6 | 4 | - | 100% (100–100%) |

| TV | 2 | - | 1 | 100% (100–100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reddy, K.; Hao, J.; Sigcu, N.; Govindasami, M.; Matswake, N.; Jiane, B.; Kgoa, R.; Kew, L.; Ndlovu, N.; Stuurman, R.; et al. Validation of Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infection Self-Testing Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131604

Reddy K, Hao J, Sigcu N, Govindasami M, Matswake N, Jiane B, Kgoa R, Kew L, Ndlovu N, Stuurman R, et al. Validation of Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infection Self-Testing Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(13):1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131604

Chicago/Turabian StyleReddy, Krishnaveni, Jiaying Hao, Nompumelelo Sigcu, Merusha Govindasami, Nomasonto Matswake, Busisiwe Jiane, Reolebogile Kgoa, Lindsay Kew, Nkosiphile Ndlovu, Reginah Stuurman, and et al. 2025. "Validation of Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infection Self-Testing Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women" Diagnostics 15, no. 13: 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131604

APA StyleReddy, K., Hao, J., Sigcu, N., Govindasami, M., Matswake, N., Jiane, B., Kgoa, R., Kew, L., Ndlovu, N., Stuurman, R., Mposula, H., Balkus, J. E., Heffron, R., & Palanee-Phillips, T. (2025). Validation of Rapid Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests for Sexually Transmitted Infection Self-Testing Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Diagnostics, 15(13), 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15131604