Forensic Cases in the Emergency Department: Associations Between Life-Threatening Risk, Medical Treatability, and Patient Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings

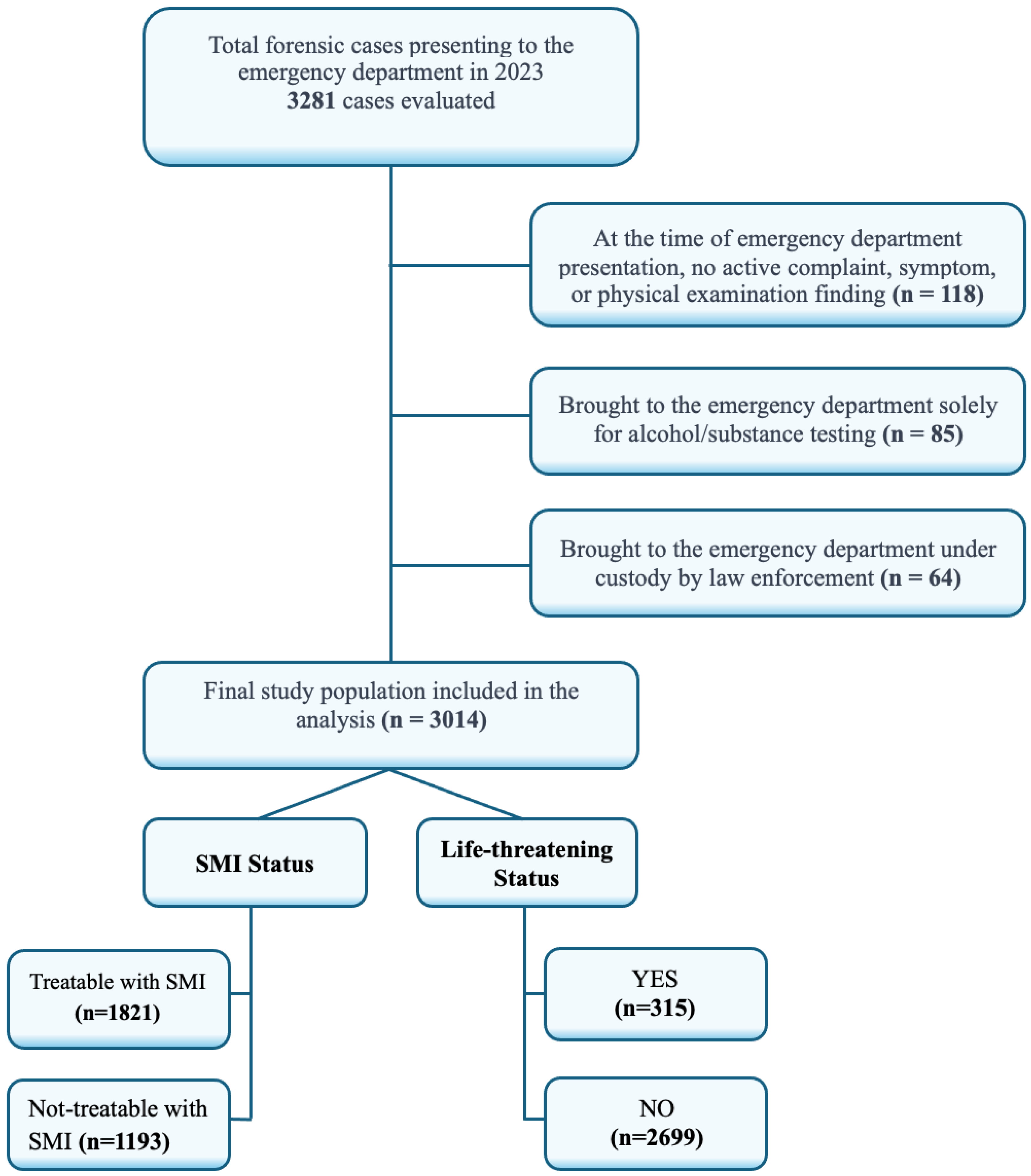

2.2. Data Source and Study Population

2.3. Variable Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Legal and Regulatory Framework

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMI | Simple medical intervention |

| ED | Emergency department |

| LTC | Life-threatening condition |

| H | Hospitalized |

| MO | Mortality |

| M | Male |

| F | Female |

References

- Terece, C.; Kocak, A.; Soğukpınar, V.; Gürpınar, K.; Aslıyüksek, H. Evaluation of forensic reports issued in emergency departments and comparison with reports issued by the Council of Forensic Medicine. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022, 28, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madadin, M.; Alqarzaie, A.A.; Alzahrani, R.S.; Alzahrani, F.F.; Alqarzea, S.M.; Alhajri, K.M.; Al Jumaan, M.A. Characteristics of medico-legal cases and errors in medico-legal reports at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2021, 13, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmankar, T.; Sharma, S. A record based study of frequency and pattern of medico-legal cases reported at a tertiary care hospital in Miraj. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 1348–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakçı, S.; Bıçakçı, N.; Şahin, H.; Saka, N.E.; Çamci, E. A retrospective one-year review of forensic reports filed in the emergency department. Namik Kemal Med. J. 2024, 12, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, M. Opportunities to preserve forensic evidence in emergency departments. Emerg. Nurse 2016, 24, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaslan, M.; Baykan, N. Analysis of patients evaluated for forensic reasons in the emergency department and the burden of battery and assault examinations on emergency care. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- De, L.M.; Jacobs, W. Forensic emergency medicine: Old wine in new barrels. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 17, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Eroğlu, S.; Toprak, S.; Karataş, A.; Onur, Ö.; Özpolat, Ç.; Salçın, E.; Denizbaşı, A. What is the meaning of temporary forensic reports for emergency physicians? Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 13, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Lemay, K.; Lee, S.; Nuth, J.; Ji, J.; Montague, K.; Garber, G.E. Medico-legal issues related to emergency physicians’ documentation in Canadian emergency departments. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 25, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulqader, S.; Alabdulqader, R.; Madadin, M.; Kashif, H.; Al Jumaan, M.A.; Yousef, A.A.; Menezes, R.G. Emergency physicians’ awareness of medico-legal case management: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcı, Y.; Çolak, B.; Gürpınar, K.; Anolay, N. Guide to the Forensic Medical Evaluation of Injury Offenses Defined in the Turkish Penal Code, 2nd ed.; Adli Tıp Uzmanları Derneği: Ankara, Turkey, 2019. Available online: https://www.atk.gov.tr/tckyaralama24-06-19.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Aktas, N.; Gulacti, U.; Lok, U.; Aydin, I.; Borta, T.; Celik, M. Characteristics of the traumatic forensic cases admitted to emergency department and errors in the forensic report writing. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2018, 6, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddappa, S.; Datta, A. A study pattern of medico-legal cases treated at a tertiary care hospital in central Karnataka. Indian J. Forensic Community Med. 2015, 2, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Atif, I.; Rashid, F.; Abbas, M. An analysis of 3105 medico legal cases at tertiary care hospital, Rawalpindi. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoon, O.K.; Shireen, F.; Seema, N.; Afzal, E.; Ahmad, I.; Irshad, R.; Sattar, H. Types of medico-legal cases reported at the casualty department of Ayub Teaching Hospital Abbottabad. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2020, 32, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shreedhar, N.C.; Chandan, V.; Shreekrishna, H.K. Retrospective study of profile of medico-legal cases at Basaveshwara medical college, Chitradurga. Med. Legal Update 2021, 21, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.; Uzun, Ş.C. Evaluation of forensic cases admitted to the emergency department: A retrospective analysis. Gümüşhane Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2023, 12, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapçı, M.; Türkdoğan, K.; Akpınar, O.; Duman, A.; Bacakoğlu, G. Demographic analysis of forensic cases evaluated in the emergency department. J. For. Med. 2015, 29, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsinha, S.; Parajuli, S. Mechanical injury among medicolegal cases in the department of emergency in a tertiary care centre: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2022, 60, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seviner, M.; Kozacı, N.; Ay, M.; Açıkalın, A.; Çökük, A.; Gülen, M.; Acehan, S.; Karanlık, M.G.; Satar, S. A retrospective analysis of forensic cases presenting to the emergency medicine clinic. Çukurova Univ. Med. Fac. J. 2013, 38, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yemenici, S.; Sayhan, M.B.; Salt, Ö.; Yılmaz, A. Evaluation of forensic reports prepared in the emergency department. Harran Univ. Med. Fac. J. 2017, 14, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Akbaba, M.; Das, V.; Asildag, M.K.; Karasu, M.; Atan, Y.; Tataroğlu, Z.; Kul, S. Are the judicial reports prepared in emergency services consistent with those prepared in forensic medicine department of a university hospital? Eurasian J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 18, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslaner, M. Revisits of forensic cases to the emergency department. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2019, 65, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüzbaşıoğlu, Y.; Çıkrıkçı, I.G. Retrospective analysis of forensic cases in refugees admitted to emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1691–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, M.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Jan, F.A.; Yatoo, G.H.; Khalil, I.; Ganai, S.; Irshad, H. Profile and pattern of medico-legal cases in a tertiary care hospital of North India. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2016, 4, 12628–12634. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Jena, S.; Singh, M.; Naik, S.; Prakash, A.; Singh, S. Profile of medico-legal cases in accident and emergency department of SSKH, LHMC, New Delhi during pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 32.9 | ±17.9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex n (%) | Male | 2028 | 67.3 |

| Female | 986 | 32.7 | |

| Seasonal Distribution n (%) | Spring | 553 | 18.3 |

| Summer | 897 | 29.8 | |

| Autumn | 853 | 28.3 | |

| Winter | 711 | 23.6 | |

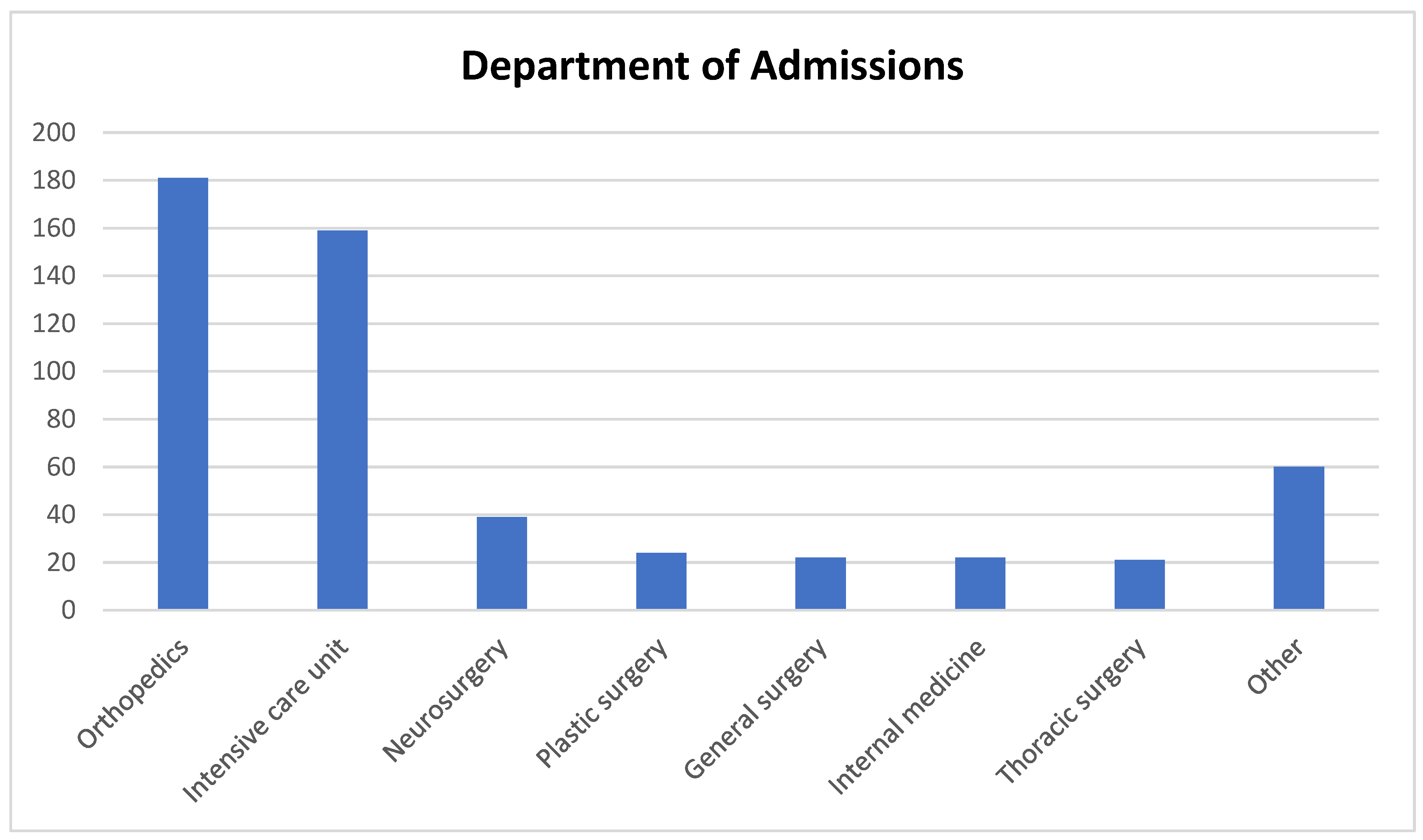

| Outcome in ED n (%) | Discharged | 2299 | 76.3 |

| Admitted to Hospital | 498 | 16.5 | |

| Refused the Treatment | 174 | 5.8 | |

| Referral to Another Hospital | 34 | 1.1 | |

| Died in ED | 9 | 0.3 | |

| Life-Threatening Condition? | Yes | 315 | 10.5 |

| No | 2699 | 89.5 | |

| Simple Medical Intervention | Treatable | 1821 | 60.4 |

| Not Treatable | 1193 | 39.6 | |

| SEX | AGE | SMI | LTC | H | MO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M 2028 (67.3) | F 964 (32.7) | Mean | Yes 1821 (60.4) | No 1193 (39.6) | Yes 315 (10.5) | No 2699 (89.5) | (+) 498 (16.5) | (+) 39 (1.3) |

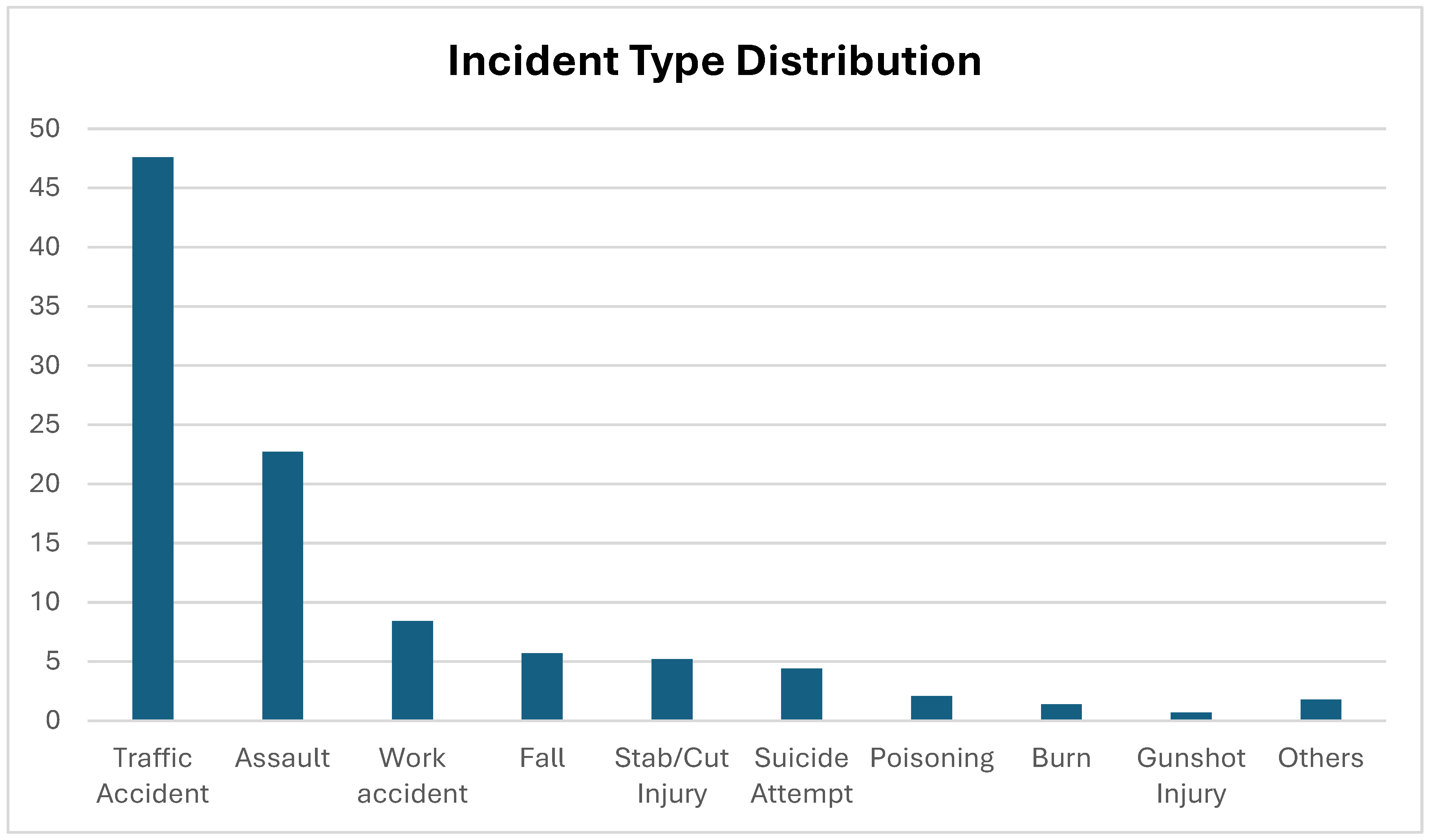

| Traffic Accident | 964 (32.0) | 472 (15.7) | 33.1 | 936 (31.1) | 500 (16.6) | 119 (3.9) | 1317 (43.7) | 245 (8.1) | 18 (0.6) |

| Assault | 427 (14.2) | 256 (8.5) | 32.3 | 551 (18.3) | 132 (4.4) | 6 (0.2) | 677 (22.5) | 20 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Work Accident | 220 (7.3) | 33 (1.1) | 35.7 | 114 (3.8) | 139 (4.6) | 19 (0.6) | 234 (7.8) | 46 (1.5) | 5 (0.2) |

| Fall | 117 (3.9) | 56 (1.8) | 33.5 | 68 (2.3) | 105 (3.5) | 40 (1.3) | 133 (4.4) | 65 (2.2) | 9 (0.3) |

| Stab/Cut Injury | 131 (4.3) | 27 (0.9) | 28.5 | 51 (1.7) | 107 (3.6) | 27 (0.9) | 131 (4.3) | 36 (1.2) | 0 (0) |

| Poisoning | 27 (0.9) | 35 (1.2) | 38.5 | 42 (1.4) | 20 (0.7) | 11 (0.4) | 51 (1.7) | 7 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Suicide Attempt | 62 (2.0) | 71 (2.4) | 31.0 | 19 (0.6) | 114 (3.8) | 67 (2.2) | 66 (2.2) | 54 (1.8) | 2 (0.1) |

| Burn | 22 (0.7) | 19 (0.6) | 20.7 | 15 (0.5) | 26 (0.9) | 9 (0.3) | 32 (1.1) | 9 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Substance/Alcohol | 18 (0.6) | 4 (0.1) | 33.5 | 10 (0.3) | 12 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) | 16 (0.5) | 4 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| Electrical Injury | 9 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | 34.5 | 6 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 11 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sexual Assault | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 24.8 | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Animal Attack | 6 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 41.7 | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 8 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Drowning | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0) | 33.3 | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Gunshot Injury | 18 (0.6) | 2 (0.1) | 39.0 | 1 (0) | 19 (0.6) | 4 (0.1) | 16 (0.5) | 8 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Suspicious Death | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 71.0 | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) |

| n (%) | Treatable with SMI 1821 (60.4) | Not Treatable with SMI 1193 (39.6) | p-Value | Life Threatening: YES 315 (10.5) | Life Threatening: NO 2699 (89.5) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1155 (57.0) | 873 (43.0) | <0.001 a | 214 (10.6) | 1814 (89.4) | 0.795 a |

| Female | 666 (67.5) | 320 (32.5) | 101 (10.2) | 885 (89.8) | |||

| Age | 31.2 ± 17.3 | 35.4 ± 18.4 | <0.001 b | 37.8 ± 20.0 | 32.3 ± 17.5 | <0.001 b | |

| Mortality | Yes | 0 (0) | 39 (100) | <0.001 c | 39 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.001 c |

| No | 1821 (61.2) | 1154 (38.8) | 276 (9.3) | 2699 (90.7) | |||

| Affected Body Region | |||||||

| Head, Neck, and Face | 561 (71.4) | 225 (28.6) | <0.001 a | 48 (6.1) | 738 (93.9) | <0.001 a | |

| Chest and Back | 157 (66.2) | 80 (33.8) | 21 (8.9) | 216 (91.1) | |||

| Abdomen, Pelvic, and Genital Regions | 97 (53.6) | 84 (46.4) | 24 (13.3) | 157 (86.7) | |||

| Upper and/or Lower Extremities | 706 (67.3) | 343 (37.2) | 17 (1.6) | 1032 (98.4) | |||

| Multiple Body Systems | 300 (39.4) | 461 (60.6) | 205 (26.9) | 556 (73.1) | |||

| Forensic Report Type | |||||||

| Preliminary Report | 574 (32.9) | 1171 (67.1) | <0.001 a | 300 (17.2) | 1445 (82.8) | <0.001 a | |

| Final Report | 1242 (99.6) | 5 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 1242 (99.6) | |||

| Not Issued | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) | 10 (45.5) | 12 (54.5) | |||

| Predictor | Estimate | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-Value | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −7.524 | −8.59 | −6.45 | <0.001 | 5.40 |

| Age | 0.039 | 0.02 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| Hospitalized | 2.819 | 2.02 | 3.61 | <0.001 | 16.76 |

| Sex | 0.540 | −0.13 | 1.21 | 0.117 | 1.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yildirim, H.; Kaya, M. Forensic Cases in the Emergency Department: Associations Between Life-Threatening Risk, Medical Treatability, and Patient Outcomes. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15111416

Yildirim H, Kaya M. Forensic Cases in the Emergency Department: Associations Between Life-Threatening Risk, Medical Treatability, and Patient Outcomes. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(11):1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15111416

Chicago/Turabian StyleYildirim, Harun, and Murtaza Kaya. 2025. "Forensic Cases in the Emergency Department: Associations Between Life-Threatening Risk, Medical Treatability, and Patient Outcomes" Diagnostics 15, no. 11: 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15111416

APA StyleYildirim, H., & Kaya, M. (2025). Forensic Cases in the Emergency Department: Associations Between Life-Threatening Risk, Medical Treatability, and Patient Outcomes. Diagnostics, 15(11), 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15111416