Abstract

Background/Objective: The accurate diagnosis of congenital central nervous system abnormalities is critical to pre- and postnatal prognostication and management. When an abnormality is found in the posterior fossa of the fetal brain, parental counseling is challenging because of the wide spectrum of clinical and neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients with Dandy–Walker (DW) spectrum posterior malformations. The objective of this study was to evaluate the utility of biometric measurements obtained from fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to facilitate the prenatal differentiation of Dandy–Walker (DW) spectrum malformations, including vermian hypoplasia (VH), Blake’s pouch cyst (BPC), and classic Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM). Methods: This retrospective single-center study evaluated 34 maternal–infant dyads referred for fetal MRI evaluation of suspected DW spectrum malformations identified on antenatal ultrasound. Radiologists took posterior fossa measurements, including the vermis anteroposterior (AP) diameter, vermis height (VH), and tegmento–vermian angle (TVA). The posterior fossa, fourth ventricle, and cisterna magna were classified as normal, large, or dilated. The postnatal imaging findings were evaluated for concordance. The acquired values were compared between the groups and with normative data. The genetic testing results are reported when available. Results: A total of 27 DW spectrum fetal MRI cases were identified, including 7 classic DWMs, 14 VHs, and 6 BPCs. The TVA was significantly higher in the DWM group compared with the VH and BPC groups (p < 0.001). All three groups had reduced AP vermis measurements for gestational age compared with normal fetal brains, as well as differences in the means across the groups (p = 0.002). Conclusions: Biometric measurements derived from fetal MRI can effectively facilitate the prenatal differentiation of VH, BPC, and classic DWM when assessing DW spectrum posterior fossa lesions. Standardizing biometric measurements may increase the diagnostic utility of fetal MRI and facilitate improved antenatal counseling and clinical decision-making.

1. Introduction

The accurate diagnosis of congenital central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities is critical to pre- and postnatal prognostication and management. Prenatal diagnosis of severe CNS anomalies may inform obstetric decision-making about fetal monitoring and route of delivery [1]. Additionally, fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmation of CNS anomalies detected on fetal ultrasound (US) prior to delivery may guide access to critical antenatal counseling, coordination of complex family-centered care for the remainder of pregnancy and delivery, and minimize separation of the mother–infant dyad, which is particularly important in the setting of life-limiting diagnoses [2]. Diagnosing CNS anomalies prior to delivery also facilitates the coordination of complex care for the infant after delivery, including delivery at tertiary care centers with access to appropriate pediatric subspecialty services. For fetal anomalies, providing information to pregnant mothers about diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that will occur in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in a multidisciplinary setting prior to delivery can help relieve parental stress and anxiety [3]. When an abnormality is found in the posterior fossa of the fetal brain, parental counseling is challenging because of the wide spectrum of clinical and neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients with Dandy–Walker spectrum posterior malformations [4].

Although CNS malformations remain quite rare, the spectrum of posterior fossa malformations, including Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM), mega cisterna magna (MCM), Blake’s pouch cyst (BPC), and vermian hypoplasia (VH), affect approximately 1 in 5000 live births [5]. The term “Dandy-Walker malformation” was coined by German Psychiatrist Clemens Ernst Benda in 1954. However, the condition itself was first described by John Bland-Sutton in 1887, with further descriptions provided by Walter Dandy and Blackfan in 1914 and Taggart and Walker in 1942 [6]. The Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM) or syndrome is a posterior fossa anomaly characterized by agenesis or hypoplasia of the vermis, cystic enlargement of the fourth ventricle with communication to a large cystic dilated posterior fossa, upward displacement of the tentorium and torcula (torcular–lambdoid inversion), and enlargement of the posterior fossa [6]. Classic DWM, VH, and MCM likely represent a continuum of congenital structural abnormalities affecting the cerebellum and posterior fossa [7]. The term “Dandy-Walker variant” was originally introduced to describe milder phenotypes, but more recently has been discouraged as a diagnostic classification due to its frequent misuse; however, this non-specific term continues to appear in regular clinical practice and the literature [8,9,10].

Although DWM can occur sporadically, genetic and chromosomal abnormalities are important factors in the etiology of DWM, with abnormalities in chromosomes 3, 9, 13, and 18 most frequently linked to posterior fossa malformations [11]. Juan et al. (2024) suggested that copy number variant (CNV) testing should be the primary diagnostic method for genetic testing in isolated posterior fossa malformations, whereas a sequential approach consisting of karyotyping, CNV testing, and whole-exome sequencing (WES) should be utilized in non-isolated posterior fossa malformations [12]. Posterior fossa malformations highlight the interplay between genetic and environmental factors in abnormalities in brain development. Although most cases are sporadic, some may result from chromosomal aneuploidy; Mendelian disorders; and environmental exposures, including viral infections and exposures to teratogens [13]. For example, cerebellar hypoplasia and VH may be seen in congenital rubella syndrome, in which maternal infection with the rubella virus early in pregnancy can disrupt the normal development of the cerebellum during early fetal development. As the cerebellum is the center for motor coordination and higher cognitive functions, posterior fossa malformations may be associated with impaired spatial navigation and musical learning ability, as well as impacting motor, sensory, cognitive, emotional, and autonomic functioning [14]. Consequently, the neurodevelopmental prognosis for children with congenital posterior fossa malformations is quite broad and significantly affected by the presence of associated genetic diagnoses or syndromes. Awareness of the developmental basis of posterior fossa malformations may facilitate improved detection of morphologic changes identified on imaging and enable more accurate differentiation and diagnosis of congenital posterior fossa anomalies [13].

Recently identified radiologic features that aid in distinguishing DWM from other posterior fossa abnormalities, such as the tail sign [15], choroid plexus/tela choroidea location [16,17], and fastigial recess shape [18], have not been incorporated consistently into standard diagnostic criteria. Classic DWM, VH, and BPC result from abnormal development of the posterior membranous area and are collectively referred to as the Dandy–Walker spectrum. The rhombic lip, a dorsal stem cell zone that drives the growth and maintenance of the posterior vermis, is specifically disrupted in DWM, with reduced proliferation and self-renewal of the progenitor pool and altered vasculature [18]. In 2021, Haldipur and colleagues proposed a unified model for the developmental pathogenesis of DWM, in which a disruption in rhombic lip development during embryonic development (through either aberrant vascularization or a direct insult) causes reduced proliferation and failed expansion of the rhombic lip progenitor pool, resulting in inferior vermis hypoplasia and dysplasia [18]. In this model, the timing of the insult to the developing rhombic lip dictates the extent of hypoplasia, distinguishing DWM caused by insult prior to 14 weeks gestation (GA) from VH caused by an insult after 14 weeks GA.

When congenital CNS abnormalities are detected during antenatal ultrasonography, fetal MRI studies are utilized for diagnostic confirmation to improve prenatal counseling and planning for the appropriate postnatal management of affected infants who may require referral to a tertiary care facility for the availability of pediatric neurosurgery, pediatric neurology, and other relevant subspecialists. Recent advances in fetal MRI characterization have enhanced the delineation of posterior fossa anomalies, including the improved identification of subtle cerebellar and vermian anomalies and their clinical implications [19]. Evaluating the structures in the posterior fossa through fetal MRI and categorizing the malformations into clinically relevant groups using routine measurements may provide high utility for accurately diagnosing these relatively rare CNS anomalies and providing better prognostication for the family and the multidisciplinary team caring for the infant after birth [20,21]. At this time, the literature on biometric measurements using fetal MRI in pregnancies affected by suspected congenital Dandy–Walker spectrum anomalies is quite limited.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the utility of biometric measurements obtained from fetal MRI to facilitate the prenatal differentiation of Dandy–Walker spectrum lesions. By examining and quantifying specific anatomical features, the authors aimed to determine whether these measurements could aid in distinguishing between VH, BPC, and classic DWM during routine clinical evaluations. The improved ability to reliably differentiate between these diagnoses antenatally may enable more accurate prognostication by maternal fetal medicine and fetal neonatal medicine providers and facilitate the delivery of infants with DWM at tertiary care facilities with appropriate resources to improve the care of these vulnerable patients and their families, while minimizing unnecessary separation of mothers and infants in the NICU for those infants with more benign findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

This was a retrospective study that involved a retrospective single-center review of a convenience sample of cases of posterior fossa malformations confirmed by fetal MRI at the Rush University Medical Center (RUMC) between 2004 and 2020. The sole inclusion criterion was a referral to the RUMC for fetal MRI based on concern after a fetal ultrasound for a CNS anomaly with fetal MRI confirmation of posterior fossa malformation. By using relevant keywords, a chart review was performed and a comprehensive list of all fetal MRIs conducted at the study center was generated, which resulted in the identification of 200 fetal MRIs through the key search. Preliminary CNS anomalies noted on routine prenatal ultrasounds were reviewed by MFM physicians. The MRI studies were retrospectively examined by the research radiologists, who excluded MR studies without a posterior fossa abnormality. Mothers referred with concern for posterior fossa malformations on fetal USs who were not able to undergo fetal MRI prior to delivery due to claustrophobia or maternal contraindications to undergoing MR scans were also excluded. The diagnostic quality of the imaging was determined by the neuroradiologists. Concordance between the fetal US, fetal MRI, and postnatal imaging was also evaluated when available. Clinical information was collected through a retrospective chart review that utilized the Rush Fetal and Neonatal Medicine Center QI database and the electronic medical record (EMR).

This study was approved by the Rush University Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of this study with all this study’s data de-identified and all fetal MRI scans obtained for routine clinical purposes based on usual and customary care.

To ensure unbiased evaluations, two independent board-certified pediatric neuroradiologists (S.E.B. and M.K. with over 15 years clinical experience), who were not aware of the participants’ clinical evaluations or the initial interpretations of the scans, reviewed the fetal MRI images. The neuroradiologists were able to establish concordance in 92% of cases. In cases of any disagreements between the two neuroradiologists, a final diagnosis was achieved by their consensus. The interobserver agreement statistics showed kappa statistics between 0.90 and 1 for the presence of DWM, VH, and BPC. This rigorous process helped ensure the objectivity and reliability of this study’s findings.

2.2. Data Collection and Management

Chart reviews were performed, and the following data were extracted from the EMR: maternal age at delivery, maternal comorbid diagnoses, maternal parity, maternal race/ethnicity, mean GA in weeks at the fetal MRI, route of delivery, known teratogenic exposures during pregnancy, amniocentesis results if performed, birth GA (completed gestational weeks), sex, and postnatal length of stay (LOS) in the General Care Nursery (GCN) or NICU after delivery. The pregnancy outcomes were categorized as termination of pregnancy, spontaneous intrauterine fetal demise, inborn live birth, or death in the neonatal period. In this study, clinical information was obtained from the pediatric neurology and genetics clinic when available. Genetic evaluation included when available, including karyotyping, chromosomal microarray analyses, and whole-exome sequencing (WES).

2.3. Scanning Parameters for Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging

At the study institution, fetal MR scans were conducted without maternal sedation using an Espree 1.5 T MR scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) T2-weighted pulse sequence. The parameters included time to echo (TE): 120 milliseconds (ms); repetition time (TR): 4300 ms; field of view (FOV): 23 (phase) × 23 (frequency) cm; slice thickness (ST): 3 mm; interslice spacing (IS): zero; and matrix: 256 (phase) × 180 (frequency) in the axial, sagittal, and coronal projections. HASTE refers to Half Fourier Single-shot Turbo spin-Echo, a single-section T2-weighted MR sequence that acquires images in less than one second.

2.4. Classification of Posterior Fossa Malformations on Fetal MRI

Two independent board-certified neuroradiologists (S.E.B. and M.K. with over 15 years of experience) reviewed all the fetal MR brain images of the participants while blinded to the clinical history. These qualified experts reviewed all the images using a Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) workstation, which is a specialized tool for managing and interpreting medical images. Each patient was categorized into one of three groups by the radiologists: BPC, VH, or classical DWM.

The morphological classification of posterior fossa malformations was originally proposed by Barkovich et al. in 1989 [22] and was subsequently refined by Klein et al. in 2003 [23], who introduced specific radiological criteria for diagnosing DWM [24]. To be classified as having classical DWM in this study, fetuses needed to meet three specific imaging criteria: (1) cystic enlargement of the fourth ventricle, (2) partial or total absence of the vermis, and (3) an enlarged posterior fossa with upward displacement of the tentorium and torcula.

The cases were categorized as VH when the smaller-than-normal vermis demonstrated a high tegmento–vermian angle (TVA) greater than 18 degrees, without any expansion of the posterior fossa. To receive a BPC diagnosis, the vermis demonstrated a size typical for gestational age, with a TVA greater than 18 degrees [21]. In this study, the radiologists measured several aspects of the posterior fossa using PACS craniocaudal (CC) height and anterior-to-posterior (AP) measuring devices. Measurements included the vermis, AP pons, and size of the largest lateral ventricle. These measurements were recorded in millimeters (mm) and rounded to the nearest mm following the methodologies described by Garel et al. in 2005 [25] and Tilea et al. in 2009 [26] for the assessment of certain parameters and the techniques outlined by Chapman et al. in 2018 [27] for evaluating the TVA and superior posterior fossa angle. The measurements obtained from the fetal MRI were compared with the normal values reported by Kline-Fath and colleagues (2020) [28].

By employing these standardized measurement techniques, the radiologists aimed to gather precise data to aid in the differentiation and characterization of the various posterior fossa anomalies within the Dandy–Walker continuum. Regarding the cisterna magna, the radiologists encountered difficulties in obtaining repeatable measurements due to vermian rotation and distortion. As a result, a cisterna magna was categorized as either normal or enlarged based on the radiologists’ visual assessment.

To validate the prenatal diagnosis of each patient, the researchers examined the postnatal brain MRI results whenever available to evaluate concordance.

Throughout this study, all authors remained blinded to the patient identifiers, and strict confidentiality was maintained regarding protected health information. The final diagnosis was arrived at by consensus.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were obtained and entered into Microsoft Excel LTSC MSO (Version 2401 Build 16.0.17231.20194) 64-bit. De-identified data were analyzed utilizing SPSS® Statistics software version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The concordance between the fetal US, fetal MRI, and postnatal imaging was assessed. Student t-tests were used for comparisons of the two groups, and ANOVAs were utilized for the comparisons of three or more groups. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Parametric tests were conducted for normally distributed data. Means and their corresponding standard deviations or median interquartile ranges are reported for quantitative variables. Frequencies are presented as percentages to represent qualitative variables.

3. Results

After a review of 200 fetal MRIs from pregnant women evaluated by the Fetal and Neonatal Medicine Center for suspected fetal CNS anomalies, a total of 34 maternal–infant dyads were identified that met this study’s inclusion criteria for fetal MRI to evaluate for concerns of posterior fossa abnormalities diagnosed on antenatal ultrasounds. Of the 34, 27 maternal–infant dyads were identified with fetal MRI findings consistent with DWM, VH, or BPC.

The remaining maternal–infant dyads were found to have non-Dandy–Walker spectrum conditions, including an isolated enlarged or prominent cisterna magna or other CNS anomalies, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Birth data, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical course.

The mean gestational age (GA) at the time of the fetal MR imaging was 26 gestational weeks. Among the Dandy–Walker spectrum cases, 7 cases were diagnosed with classic DWM, 13 cases were categorized as VH, and 6 cases were classified as BPC. This study’s findings revealed that the cisterna magna was enlarged in 100% (7/7) of patients with DWM, which was a higher frequency compared with the VH group (50%, 7/14) and the BP group (50%, 3/6), as indicated in Table 2. The concordance of the prenatal US, fetal MRI, and postnatal imaging are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Posterior fossa measurements for Dandy–Walker spectrum disorders.

Table 3.

Concordance of prenatal US, fetal MRI, and postnatal imaging findings.

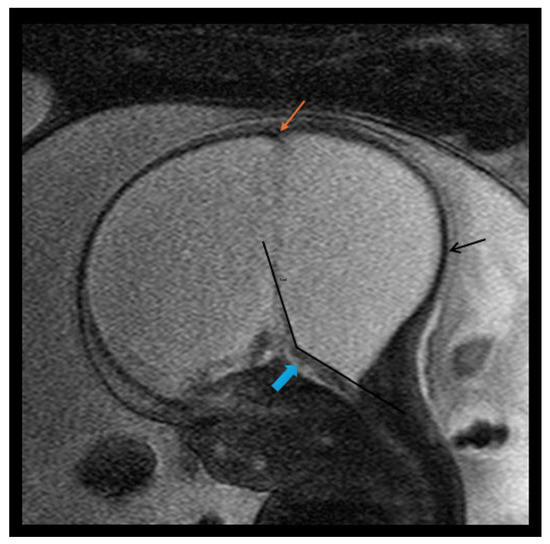

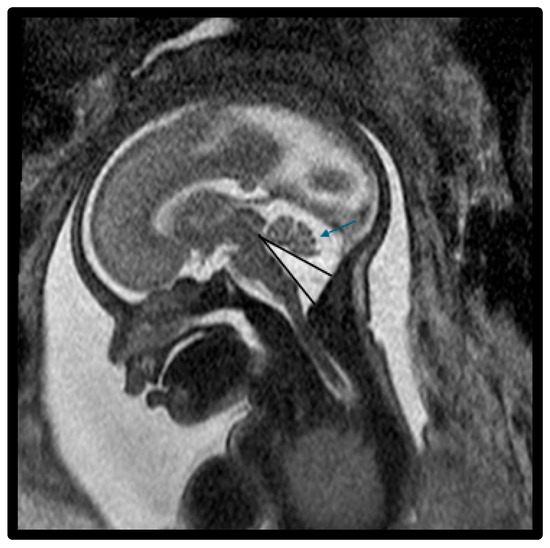

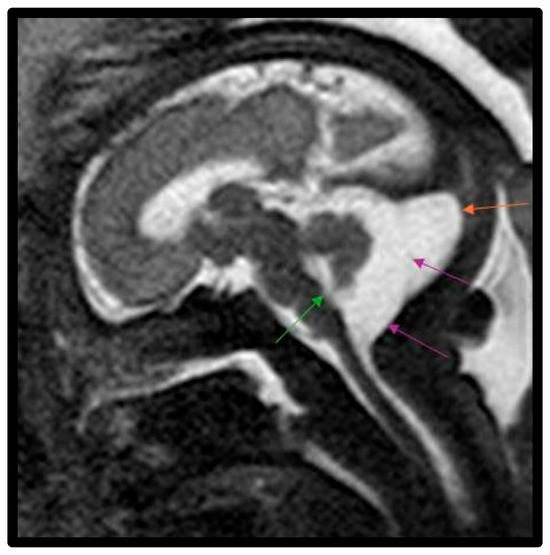

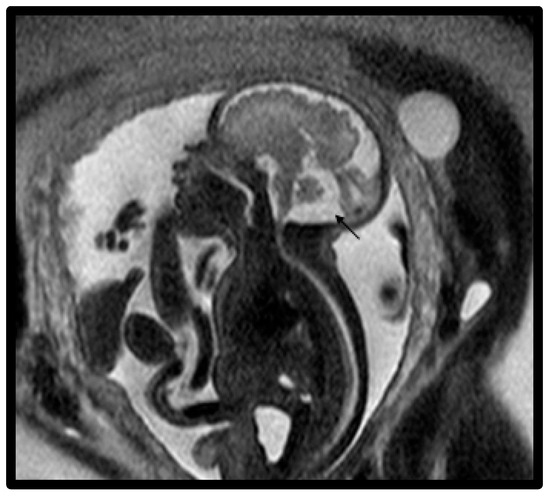

In this study, a total of 27 maternal–infant dyads were found to have Dandy–Walker spectrum posterior fossa malformations on the fetal MRI. Six had abnormal results from genetic testing, with an additional infant diagnosed with congenital CMV and another with maternal Coxsackie infection (Table 4). Abnormal genetic testing results in the case series are detailed as follows, with additional details of the postnatal course in Table 4. Figure 1 depicts a fetal MRI of a preterm infant with classic DW cyst. Figure 2 depicts a fetal MRI image of a fetus at 25 gestational weeks with vermian hypoplasia. Figure 3 depicts a fetal MRI image of a fetus at 33 gestational weeks with a Blake’s pouch cyst. Figure 4 depicts a fetal MRI image of a fetus at 32 gestational weeks with an enlarged cisterna magna.

Table 4.

Case series with genetic testing and clinical course.

Figure 1.

Fetal MRI image of a fetus at 31 gestational weeks with a classical Dandy–Walker cyst and massive hydrocephalus with a possible form of encephaloclastic schizencephaly. The T2-weighted sequence in the sagittal plane depicts a large posterior fossa cyst representing massive enlargement of the 4th ventricle as part of a large classical Dandy–Walker cyst. Pictured is an enlarged intracranial cavity occupied almost completely by CSF, a large posterior fossa cyst with ballooning of the occiput (black arrow), and a thin brainstem (blue arrow) with anterior displacement. There was no evidence of a cerebellum and there was elevation of torcular implantation (orange arrow) and an increased tegmento–vermian angle (black lines). There were enlarged lateral ventricles secondary to the massive hydrocephalus and/or a form of encephaloclastic schizencephaly.

Figure 2.

Fetal MRI image of a fetus at 25 gestational weeks with vermian hypoplasia. The midline T2-weighted sagittal image shows an enlarged fourth ventricle, decreased vermian biometry, and enlarged fluid space of the posterior fossa. There was mild hypoplasia of the postero-inferior vermis with slight upward rotation (blue arrow) and increased tegmento–vermian angle (black lines). The fastigial recess was shallow and there was mild widening of the vallecula, the midline outlet of the fourth ventricle. There was a prominent and abnormal fourth ventricle with a loss of the normal diamond shape. The fourth ventricle is shown inferiorly connecting with a prominent cisterna magna through the vallecula.

Figure 3.

Fetal MRI image of a fetus at 33 gestational weeks with a Blake’s pouch cyst. The T2-weighted sequence in the sagittal plane depicts a slight widening of the midline outlet of the 4th ventricle (green arrow). There is a membrane within the midportion of the CSF space of the cisterna magna with slight bowing of this membrane posteriorly, which is consistent with a Blake’s pouch cyst (purple arrows) involving posterior fossa within this enlarged cisterna magna (orange arrow). The cyst freely communicated with the fourth ventricle with upward displacement of the vermis and elevation of the tentorium.

Figure 4.

Fetal MRI image of a fetus at 32 gestational weeks with an enlarged cisterna magna. The midline T2-weighted sagittal image shows an enlarged cisterna magna (1.2–1.4 cm) and increased CSF subarachnoid spaces overlying the cerebellum (black arrow). The fourth ventricle did not communicate with the cisterna magna and there was a normally inserted torcula.

- ❖

- Case 1 with DWM was noted to have hydrocephalus, markedly elevated CPK, bilateral talipes equinovarus deformity, overlapping fingers, a vertebral anomaly consisting of fusion of the second and third ribs, and retinal dysgenesis and was clinically diagnosed with Walker–Warburg syndrome.

- ❖

- Case 7 with DWM had a postnatal microarray, which identified a pathogenic 4.1 Mb loss at 3q24q25.1, including Z1C1 and Z1C4, which has been proposed as a critical region for brain anomalies. The entire deleted interval included 32 genes, of which 8 (Z1C1, RNF13, MED12L, HPS3, GYG1, CP, CRLN1, P2RY12) are associated with known clinical disorders.

- ❖

- Case 8 with DWM had one pathogenic change in ASPMc.7783_7786del, p.Lys2595Tyrfs 20 (AR primary microcephaly); a hetA VUS change in TUBGCP4 (AR) c.602G>A, p.Gluy201Asp; and a het A VUS change in MAPK8IP (AD) c.1057G>C, p.Asp353His, het identified.

- ❖

- Case 14 with VH was found to have a duplication of material on the long arm of chromosome X, including part of the FMR1 and AS1-FMR1 genes. In general, a loss of function of the FMR1 gene leads to Fragile X syndrome. It is not clear whether disruption of the gene would lead to a partial or complete loss of FMR1 function, especially since the disruption resulted in a duplication. In this patient, the CNS findings, including microcephaly, were explained by congenital CMV, as urine CMV testing on admission was positive with >3 million copies.

- ❖

- Case 19 with VH was diagnosed with Trisomy 13.

- ❖

- Case 31 with VH, cerebellar hypoplasia, moderate dilation of the lateral ventricles, and mild-to-moderate dilation of the 3rd ventricle was diagnosed with Smith–Lemli–Opitz Syndrome. Additional abnormalities for this infant included balanced AV canal Rastelli type 1 with no coarctation, posterior cleft palate, optic nerve dysplasia, infantile cataracts of both eyes, hearing loss, left talipes equinovarus, bilateral hand and foot polydactyly, a right hip dislocation, and restrictive lung disease due to scoliosis.

4. Discussion

In our study, we evaluated maternal–infant dyads whose pregnancy was complicated by a fetus with a Dandy–Walker spectrum CNS anomaly diagnosed on fetal MRI, including 7 with classic DWM cyst, 14 with VH, and 6 with BPC. The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of biometric measurements obtained from fetal MRI in the evaluation of posterior fossa lesions, specifically those along the Dandy–Walker spectrum. We conducted a retrospective single-center review of 200 mothers referred for fetal MRI evaluation due to suspected CNS anomalies, with 34 referred with concern or posterior fossa malformations. Of these, we included 27 with Dandy–Walker spectrum anomalies with fetal MRIs of diagnostic quality. In our cohort, we found that the TVA was significantly higher in the DWM group than in the VH and BP groups (Table 2, p < 0.001), as well as when compared with commonly used fetal imaging metrics [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The anterior-to-posterior (AP) vermis measurements were significantly different between the groups (Table 2, p < 0.002), and we observed reduced anterior-to-posterior (AP) vermis measurements in all three groups when compared with normal fetal brains [29]. Regarding cisterna magna (CM) enlargement, all patients with DWM and half of the patients with VH and BPC subtypes exhibited CM enlargement. The percentage of patients with CM enlargement across the three groups was significantly different (Table 2, p < 0.002), suggesting a potential association between CM enlargement and the severity of the Dandy–Walker spectrum.

Fetal MRI is an interactive scanning of the moving fetus that is becoming an increasingly valuable noninvasive tool for evaluating fetal abnormalities [30,31]. Due to the low prevalence of fetal CNS abnormalities, many community obstetricians performing screening ultrasounds have limited exposure to congenital brain abnormalities [32]. Thus, for suspected fetal CNS anomalies identified on routine antenatal ultrasound, fetal MRI has become an essential method for evaluating the fetal brain, facilitating a diagnostic confirmation and improved prognostic information regarding fetal CNS anomalies and permitting improved parent counseling and determination of the delivery location at tertiary care centers for affected patients with access to appropriate pediatric subspecialists, including pediatric neurosurgery and neurology services [33]. The MERIDIAN diagnostic accuracy study evaluated 570 fetuses to diagnose fetal developmental brain abnormalities utilizing fetal MRI [34]. The investigators found that US and fetal MRI have absolute diagnostic accuracies of 68 and 93 percent, respectively. With increasing gestational age, the disparity between US and fetal MRI increased. Pregnant mothers tolerated the procedure well, with 95% of the responders saying they would have fetal MRI again in a similar situation. According to health professional interviews, fetal MRI was acceptable to physicians and considered beneficial as a supplement to US, but not as a replacement. When compared with US alone, fetal MRI resulted in a higher cost. Additionally, there may be reporting bias from referring clinicians on diagnostic and prognostic outcomes. The authors suggested that using fetal MRI as an adjuvant to US enhances the diagnostic accuracy and confidence in the diagnosis of prenatal brain disorders [34]. In our cohort, there was not a significant difference between the accuracy of the fetal US and fetal MRI for the diagnosis of posterior fossa lesions (Table 3).

Accurately detecting posterior fossa anomalies along the Dandy–Walker spectrum before birth presents distinct clinical implications for the postnatal management of these infants, as well as the delivery location and urgency of postnatal imaging. DW spectrum disorders can have a wide spectrum of clinical and neurodevelopmental outcomes requiring pediatric subspecialty care, including neonatology, neurology, pediatric radiology, neurosurgery, genetics, physical therapy, and speech language pathology. When community obstetricians identify concern for a CNS abnormality on routine screening, referral to an MFM for confirmatory testing is warranted. Fetal MRI confirmation of posterior fossa abnormalities identified on prenatal ultrasound can facilitate the antenatal counseling of parents and permit the coordination of care to facilitate delivery at tertiary or quaternary care centers with access to pediatric subspecialists. In our cohort, classic DWM was associated with unifying genetic diagnoses or syndromes in three out of nine patients (33%), including a diagnosis of Walker–Warburg syndrome (Case 1 in Table 3 and Table 4), which is notable for microcephaly, overlapping fingers, bilateral talipes equinovarus deformities, hypotonicity with absent suck/swallow, and retinal dysgenesis. This infant was discharged with home hospice on TPN via a Broviac catheter due to oral feeding intolerance. A second infant (Case 7 in Table 3 and Table 4) with classic DWM was noted to have a pathogenic 4.1 Mb loss at 3q24q25.1, including ZIC1 and ZIC4 genes, a critical region for brain anomalies that explains the infant’s clinical findings. A third infant with classic DWM (Case 8 in Table 3 and Table 4) was found to have a pathogenic change in the ASPM gene, which was inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion and has been associated with primary microcephaly, along with several VUSs. A normal karyotype was identified in four of the nine infants with classic DWM and no genetic testing was available for two outborn infants. Four out of nine of our cohort with classic DWM required a VP shunt placement in infancy or early childhood.

For infants with imaging consistent with VH in our cohort, genetic testing or screening was normal in 8 out of 17 cases. No testing was available for five infants. One patient with VH (Case 14, Table 3) had congenital CMV with associated severe microcephaly, a blueberry muffin rash, calcifications on the head imaging, retinitis, and lower extremity spasticity. This patient also had a duplication of material on the long arm of chromosome X, including part of the FMR1 and AS1-FMR1 genes, although congenital CMV infection was likely the etiologic environmental exposure for this infant. One patient with VH (Case 19, Table 3 and Table 4) was found to have Trisomy 13, which is known to be associated with posterior fossa malformations. One interesting case (Case 23, Table 3 and Table 4) of VH was associated with a heterozygous VUS in the BRAF gene, as well as titers concerning for maternal Coxsackie virus infection during pregnancy. This infant had an associated right ectopic kidney in the iliac fossa; two VSDs; a supernumerary nipple; and multiple midline lesions, including epulis of the gum, a cyst on the lip, and right-sided sensorineural hearing loss.

Clinically, MCM and arachnoid cysts are usually considered incidental findings, whereas cysts in the DW spectrum are associated with other developmental anomalies of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis and often present with hydrocephalus early in life [35]. A mega CM communicates freely with both the fourth ventricle and subarachnoid space. The arachnoid mater, the middle layer of the meninges, is a thin, avascular membrane that separates the dura mater and pia mater, with the subarachnoid space containing CSF in between. A posterior fossa arachnoid cyst represents a CSF collection within duplicated layers of the arachnoid, which may communicate directly with the subarachnoid space. Both the MCM and arachnoid cysts may exert mass effects on the cerebellum or progress to hydrocephalus, but less frequently than in DW spectrum disorders.

Within the radiological spectrum of posterior fossa cysts and cyst-like malformations, BPC is a distinct entity with clinical signs and symptoms that may range from asymptomatic to hydrocephalus [35,36,37]. Isolated BPC is radiologically characterized by a normal-sized vermis with an elevated TVA. A fastigial angle measurement on fetal MRI may be a reliable adjunct in distinguishing BPC from VH, especially when the vermis size is borderline [38]. Children with isolated BPC generally have a favorable neurodevelopmental prognosis; however, close monitoring by the pediatrician and pediatric neurosurgery is advised due to the possibility of postnatal obstructive hydrocephalus requiring shunting [36,37]. One case series of six children with BPC emphasized their initial radiological uniformity coupled with widely variable clinical presentations. This case series included one patient who died in infancy after developing marked hydrocephalus with high intracranial pressure, leading to massive cerebral ischemia in the setting of hemorrhagic BPC, which was complicated by vitamin K deficiency from biliary atresia [36]. A previously healthy child with isolated BPC presented at 2 years of age with gait impairment from progressive hydrocephalus that was corrected with shunting via an endoscopic third ventriculostomy [36]. This case series also included a previously healthy patient who presented at age 69 years when he developed gait disturbance, memory impairment, dysphasia, headaches, nausea, blurred vision, and opisthotonus. This patient was ultimately diagnosed with BPC complicated by obstructive hydrocephalus, which required treatment with an endoscopic third ventriculostomy. Other patients with BPC have compensated hydrocephalus that may not require neurosurgical treatment, although continued close monitoring is advised. Accordingly, infants diagnosed using fetal imaging with BPC will benefit from proactive monitoring by their pediatrician and neurosurgery, allowing for timely neurosurgical intervention when needed and watchful waiting for those infants and children whose head circumferences stabilize with the normal progression of developmental milestones. In our cohort, the infants diagnosed with BPC all had normal genetic testing.

The long-term neurodevelopmental consequences of isolated VH remains poorly defined, with inconsistencies in the classification of cerebellar anomalies further obscuring the prognostic picture. In one cohort, infants with isolated posterior fossa abnormalities diagnosed on fetal MRI typically had normal neurological outcomes, while those with additional anomalies demonstrated higher morbidity and mortality [14]. In another recent cohort study, fetuses with classic DWM were more likely to have associated CNS anomalies and required more postnatal intervention(s) compared with those diagnosed with BPC or VH [11]. A study that evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes in patients diagnosed with isolated VH on fetal MRI indicated that although children with postnatally confirmed isolated inferior VH had an overall lower mean developmental performance compared with infants with normal postnatal MRI, all children were free of major neurodevelopmental impairment and disability, suggesting a relatively benign outcome at preschool age [39]. A follow-up study evaluated these children at school age and found that 17/20 children with postnatal confirmation of isolated VH had normal cognitive, language, social, and behavioral outcomes [40]. The authors found that more extensive cerebellar malformations or chromosomal anomalies were strongly associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes in these patients [40]. Despite the benign functional outcome of children with isolated VH, parents of these children carry an elevated and enduring burden of stress.

In our cohort, as in the literature [23,41,42], the infants with more extensive cerebellar malformations and associated genetic diagnoses had a substantially higher burden of morbidity and mortality. In this series of 34 mother–infant dyads referred with concern for posterior fossa abnormalities on fetal imaging, we identified six such cases with DW spectrum malformations associated with genetic diagnoses, including Walker–Warburg syndrome, Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, and Trisomy 13. Congenital CMV infection was suspected as the underlying etiology in one patient in our cohort. Pathogenic deletions and duplications in critical regions for brain anomalies were also identified. As the availability of rapid whole-genome genetic testing improves, correlating the results of genetic testing with the DW spectrum phenotype on fetal MRI may enable more accurate prognostication. A sequential genetic testing strategy—starting with chromosomal microarray and copy number variant (CNV) testing followed by whole-exome sequencing (WES) in non-isolated posterior fossa malformations—significantly improves the diagnostic yield and is recommended for optimal prenatal genetic diagnosis. In a study by Zhang et al., this approach led to a 47.5% detection rate in non-isolated PFMs, while isolated cases had a lower yield, supporting a tiered testing strategy [12]. Postnatal brain MRI for the confirmation of antenatal findings remains critical for infants diagnosed with DW spectrum anomalies on fetal imaging, as false positive abnormal fetal MRI results have been reported in the literature, particularly with isolated VH [8].

The present study significantly contributes to the existing body of literature by reporting on the biometric measurements of the posterior fossa obtained from fetal MR imaging in a substantial sample of patients with confirmed diagnoses of malformations involving posterior fossa along the Dandy–Walker spectrum. Moreover, the inclusion of postnatal imaging validation and clinical follow-up enhances the significance and clinical relevance of our findings. Improving the accuracy of fetal diagnostics may enable better patient counseling and management approaches, as well as the appropriate utilization of resources for patients who require close multidisciplinary follow-up given the risk of progressive hydrocephalus and neurodevelopmental impairment. Emerging artificial intelligence tools are being developed to automate the segmentation of fetal brain structures on MRI, which may improve the diagnostic reproducibility in posterior fossa malformations and enable the early prediction of postnatal neurodevelopmental outcomes [43]. Additionally, the need for genetic testing to identify associated genetic syndromes can permit more accurate prognostication for these patients and their families and alleviate some of the uncertainty that contributes to increased stress and anxiety for caregivers of these children.

This study contributes to the limited literature on fetal MR imaging biometric assessments in patients with posterior fossa abnormalities. The standardization of these measurements can facilitate the routine clinical practice of evaluating posterior fossa features on prenatal MR imaging. The sample size in this study was small, and therefore, additional research with larger sample sizes is essential to confirm and validate these findings.

Study Limitations

We wish to acknowledge several limitations that could impact the interpretation and generalizability of these findings. The myriad terminologies used in the context of the Dandy–Walker spectrum raise concerns about the applicability of our findings to clinical practice beyond our institution. To reduce confusion and enhance precise prognostication, certain fetal imagers have suggested refraining from using the term “Dandy-Walker variant” and instead considering a small and rotated vermis as an imaging phenotype rather than a primary diagnosis. This approach is particularly relevant when considering genetic abnormalities, as genetic mutations have been found to be more commonly associated with cerebellar hypoplasia than with a classic Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM). Furthermore, there is a suggestion that the severity of imaging findings in the posterior fossa alone may not always accurately correlate with the severity of the clinical phenotype [8].

One major limitation was the retrospective design of this study, which introduced inherent biases and restricted the internal validity. Moreover, this study’s single-institution nature and the temporal constraints of data collection may limit the external validity of the findings. Considering the acknowledged variability and overlapping imaging findings within the Dandy–Walker spectrum, the diagnostic categories utilized in this study might be subject to scrutiny, particularly due to inconsistent terminology and criteria used in the existing literature.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study emphasized the potential value of biometric measurements derived from fetal MRI when assessing and confirming posterior fossa lesions along the Dandy–Walker spectrum detected on prenatal ultrasound. We found that biometric measurements derived from fetal MRI could effectively facilitate the prenatal differentiation of VH, BPC, and classic DWM when assessing DW spectrum posterior fossa lesions. Standardizing biometric measurements may increase the diagnostic utility of fetal MRI in clinical practice and facilitate improved antenatal counseling and clinical decision-making when fetal CNS anomalies are suspected. Further research with larger sample sizes and longitudinal neurodevelopmental outcome data is warranted to validate these findings and advance our understanding of fetal brain development and the neurodevelopmental implications of posterior fossa lesions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.B.; methodology, S.E.B. and M.K.; software, X.L.; validation, S.E.B., R.M.B. and K.K.M.; formal analysis, S.E.B., R.M.B. and K.K.M.; investigation, S.A., S.E.B., K.K.M., R.M.B., M.P. and J.O.A.; resources, S.E.B., K.K.M. and F.V.; data curation, M.P., J.O.A. and R.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.B. and K.K.M.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, K.K.M. and F.V.; supervision, S.E.B. and R.M.B.; project administration, S.E.B.; funding acquisition, S.E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Colonel Robert R. McCormick Professorship of Diagnostic Imaging Fund at Rush University Medical Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Rush University Institutional Review Board (protocol code: 20070702-IRB01, date of approval: 9 July 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (with data availability limited by patient privacy).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Departments of Pediatrics and Radiology at Rush University Medical Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tan, A.G.; Sethi, N.; Sulaiman, S. Evaluation of prenatal central nervous system anomalies: Obstetric management, fetal outcomes and chromosomal abnormalities. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garel, C.; Moutard, M.L. Main congenital cerebral anomalies: How prenatal imaging aids counseling. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2014, 34, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorayeb, R.P.; Gorayeb, R.; Berezowski, A.T.; Duarte, G. Effectiveness of psychological intervention for treating symptoms of anxiety and depression among pregnant women diagnosed with fetal malformation. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2013, 121, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antonio, F.; Khalil, A.; Garel, C.; Pilu, G.; Rizzo, G.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Bhide, A.; Thilaganathan, B.; Manzoli, L.; Papageorghiou, A.T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of isolated posterior fossa malformations on prenatal imaging (part 2): Neurodevelopmental outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Kumar, M.; Rai, P.; Srivastava, S.S.; Gupta, A.; Roy, C.S. Relative prevalence and outcome of fetal posterior fossa abnormality. J. Pediatr. Child. Health. 2023, 59, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, E.A.; Das, J.M.; Ahmad, T. Dandy-Walker Malformation. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Raybaud, C.A. Congenital malformations of the brain and skull. In Pediatric Neuroimaging, 6th ed.; Barkovich, A.J., Raybaud, C.A., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; p. 531. [Google Scholar]

- Wüest, A.; Surbek, D.; Wiest, R.; Bonel, H.; Steinlin, M.; Raio, L.; Tutschek, B. Enlarged posterior fossa on prenatal imaging: Differential diagnosis, associated anomalies and postnatal outcome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman-Sagie, T.; Prayer, D.; Stöcklein, S.; Malinger, G. Fetal cerebellar disorders. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 155, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj, U.D.; Kline-Faith, B.M.; Horn, P.S.; Venkatesan, C. Evaluation of posterior fossa biometric measurements on fetal MRI in the evaluation of Dandy-Walker spectrum. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 1716–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsehli, H.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Alzahrani, S.; Ababneh, F.; Alharbi, N.M.; Alarfaj, N.; Baarmah, D. Fetal and neonatal outcomes of posterior fossa anomalies: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Han, J.; Zhang, G.; Yan, Y.; et al. Optimal prenatal genetic diagnostic approach for posterior fossa malformation: Karyotyping, copy number variant testing, or whole-exome sequencing? Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 397. [Google Scholar]

- Cotes, C.; Bonfante, E.; Lazor, J.; Jadhav, S.; Caldas, M.; Swischuk, L.; Riascos, R. Congenital basis of posterior fossa anomalies. Neuroradiol. J. 2015, 28, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Şeker, E.; Aslan, B.; Aydın, E.; Koç, A. Long-term outcomes of fetal posterior fossa abnormalities diagnosed with fetal magnetic resonance imaging. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2023, 24, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, S.; Vinci, V.; Saldari, M.; Servadei, F.; Silvestri, E.; Giancotti, A.; Aliberti, C.; Porpora, M.G.; Triulzi, F.; Rizzo, G.; et al. Dandy-Walker malformation: Is the ‘tail sign’ the key sign? Prenat. Diagn. 2015, 35, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M.T.; Vezina, G.; Schlatterer, S.D.; Mulkey, S.B.; Plessis, A.J. Taenia-tela choroidea complex and choroid plexus location help distinguish Dandy-Walker malformation and Blake pouch cysts. Pediatr. Radiol. 2021, 51, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladini, D.; Donarini, G.; Parodi, S.; Volpe, G.; Fulcheri, E. Hindbrain morphometry and choroid plexus position in differential diagnosis of posterior fossa cystic malformations. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldipur, P.; Bernardo, S.; Aldinger, K.A.; Sivakumar, T.; Millman, J.; Sjoboen, A.H.; Dang, D.; Dubocanin, D.; Deng, M.; Timms, A.E.; et al. Evidence of disrupted rhombic lip development in the pathology of Dandy-Walker malformation. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; O’Keane, A.; Vande Perre, S.; Chanclud, J.; Pointe, H.D.; Garel, C.; Blondiaux, E. Fetal imaging of posterior fossa malformations. Pediatr. Radiol. 2025, 55, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J. Inferior vermian hypoplasia--preconception, misconception. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 43, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, A.J.; Ederies, M.A. Diagnostic imaging of posterior fossa anomalies in the fetus. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 21, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Kjos, B.O.; Norman, D.; Edwards, M.S. Revised classification of posterior fossa cysts and cystlike malfor-mations based on the results of multiplanar MR imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1989, 10, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, O.; Pierre-Kahn, A.; Boddaert, N.; Parisot, D.; Brunelle, F. Dandy-Walker malformation: Prenatal diagnosis and prognosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2003, 19, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nora, A.; Costanza, G.; Pizzo, F.; Di Mari, A.; Sapuppo, A.; Basile, A.; Fiumara, A.; Pavone, P. Dandy-Walker malformation and variants: Clinical features and associated anomalies in 28 affected children-a single retrospective study and a review of the literature. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2023, 123, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garel, C. Fetal cerebral biometry: Normal parenchymal findings and ventricular size. Eur. Radiol. 2005, 15, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilea, B.; Alberti, C.; Adamsbaum, C.; Armoogum, P.; Oury, J.F.; Cabrol, D.; Sebag, G.; Kalifa, G.; Garel, C. Cerebral biometry in fetal magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 33, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, T.; Menashe, S.J.; Zare, M.; Alessio, A.M.; Ishak, G.E. Establishment of normative values for the fetal posterior fossa by magnetic resonance imaging. Prenat. Diagn. 2018, 38, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline-Fath, B.; Bulas, D.I.; Lee, W. Fundamental and Advanced Fetal Imaging, 2nd ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, T.; Mahalingam, S.; Ishak, G.E.; Nixon, J.N.; Siebert, J.; Dighe, M.K. Diagnostic imaging of posterior fossa anomalies in the fetus and neonate: Part 2, Posterior Fossa Disorders. Clin. Imaging 2015, 39, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S.N. Fetal MRI: An approach to practice: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 5, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, E.; Baschat, A.; Huisman, T.A.G.M.; Tekes, A. Value of Fetal MRI in the Era of Fetal Therapy for Management of Abnormalities Involving the Chest, Abdomen, or Pelvis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 210, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Catte, L.; De Keersmaeker, B.; Claus, F. Prenatal neurologic anomalies: Sonographic diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr. Drugs. 2012, 14, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.D.; Bradburn, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Graham, R.; Jarvis, D.; Kilby, D.M.; Mason, G.; Mooney, C.; Robson, S.C.; et al. Use of MRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities in utero (MERIDIAN): A multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 389, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.D.; Bradburn, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Embleton, N.; Graham, R.; Hart, A.R.; Jarvis, D.; Kilby, M.D.; Lie, M.; et al. MRI in the diagnosis of fetal developmental brain abnormalities: The MERIDIAN diagnostic accuracy study. Health Technol. Assess. 2019, 23, 1–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gandolfi, C.G.; Contro, E.; Carletti, A.; Ghi, T.; Campobasso, G.; Rembouskos, G.; Volpe, G.; Pilu, G.; Volpe, P. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetal posterior fossa fluid collections. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 39, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornips, E.M.; Overvliet, G.M.; Weber, J.W.; Postma, A.A.; Hoeberigs, C.M.; Baldewijns, M.M.; Vles, J.S. The clinical spectrum of Blake’s pouch cyst: Report of six illustrative cases. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2010, 26, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj, U.D.; Kline-Fath, B.M.; Calvo-Garcia, M.A.; Vadivelu, S.; Venkatesan, C. Fetal and postnatal MRI findings of Blake pouch remnant causing obstructive hydrocephalus. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020, 15, 2535–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, L.; Rangasami, R.; Priyanka, C.; Suresh, I.; Suresh, S. Assessment of fastigial angle in fetuses with Blake pouch cyst and vermian hypoplasia on magnetic resonance imaging. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 2024, 19, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limperopoulos, C.; Robertson, R.L.; Estroff, J.A.; Barnewolt, C.; Levine, D.; Bassan, H.; Plessis, A.J. Diagnosis of inferior vermian hypoplasia by fetal magnetic resonance imaging: Potential pitfalls and neurodevelopmental outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarui, T.; Limperopoulos, C.; Sullivan, N.R.; Robertson, R.L.; Plessis, A.J. Long-term developmental outcome of children with a fetal diagnosis of isolated inferior vermian hypoplasia. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014, 99, F54–F58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patek, K.J.; Kline-Fath, B.M.; Hopkin, R.J.; Pilipenko, V.V.; Crombleholme, T.M.; Spaeth, C.G. Posterior fossa anomalies diagnosed with fetal MRI: Associated anomalies and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Prenat. Diagn. 2012, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antonio, F.; Khalil, A.; Garel, C.; Pilu, G.; Rizzo, G.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Bhide, A.; Thilaganathan, B.; Manzoli, L.; Papageorghiou, A.T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of isolated posterior fossa malformations on prenatal ultrasound imaging (Part 1): Nomenclature, diagnostic accuracy and associated anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 47, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedifard, F.; Adepoju, J.O.; Supanich, M.; Ai, H.A.; Liu, X.; Kocak, M.; Marathu, K.K.; Byrd, S.E. Review of deep learning and artificial intelligence models in fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 3725–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).