The Characteristics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma and the Particularities for Elderly Patients—Experience of a Single Clinic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

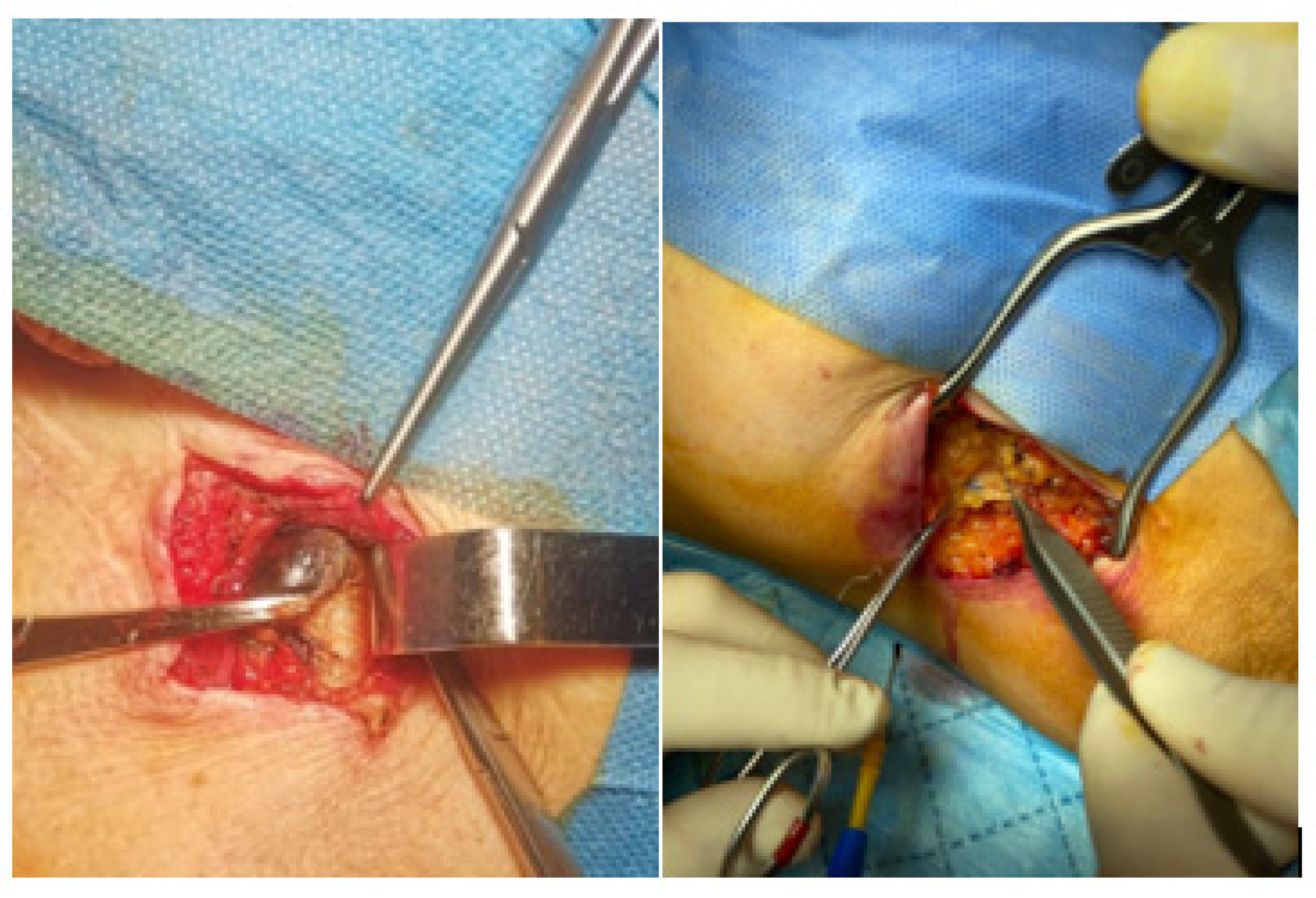

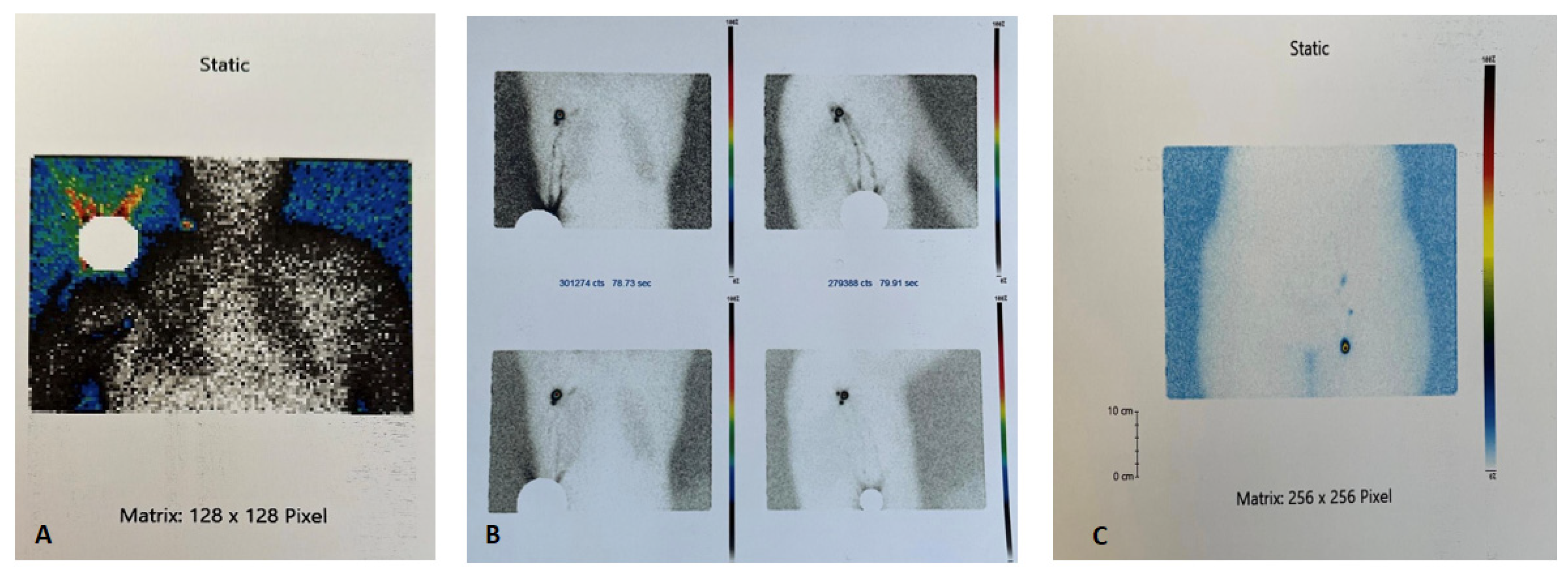

Sentinel Lymph Node Surgical Technique

3. Results

| N = 162 | Cervical N = 39 | Axillar N = 83 | Inguinal N = 40 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive SLN | 33, 20.4% | 4, 10.3% | 19, 22.9% | 10, 25.0% | 0.191 |

| Scar (melanoma) | 10,000.0 | 17,700.0 | 18,500.0 | 18,000.00 | 0.521 |

| Median (min,max) | (1900–30,000) | (1900–30,000) | (2200–30,000) | (3000–30,000) | |

| Preoperative | 655.0 | 760.0 | 550.0 | 783.0 | 0.015 |

| Median (min,max) | (20–18,000) | (90–18,000) | (20–2700) | (46–2800) | |

| During surgery | 1335.0 | 1200.0 | 1200.0 | 1700.0 | 0.184 |

| Median (min,max) | (60–12,000) | (220–7500) | (60–12,000) | (120–7050) | |

| Ex vivo | 1500.0 | 1000.0 | 1500.0 | 1600 | 0.030 |

| Median (min,max) | (50–9100) | (130–7600) | (50–9100) | (140–6900) | |

| Ganglion site healing period (days) mean ± SD | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 7.73 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 0.014 |

- Characteristics of patients 70 years old or older

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; Del Marmol, V.; Dréno, B.; Fargnoli, M.C.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 1: Diagnostics: Update 2022. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 170, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Cancer Information System. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/factsheets.php (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Whiteman, D.C.; Green, A.C.; Olsen, C.M. The Growing Burden of Invasive Melanoma: Projections of Incidence Rates and Numbers of New Cases in Six Susceptible Populations through 2031. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, M.T.; Patrascu, T.; Serbanescu, L.G.; Anghel, R.M.; Gales, L.N.; Georgescu, F.T.; Mitrica, R.I.; Georgescu, D.E. When Should We Expect Curative Results of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Patients? Chirurgia 2021, 116, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, Y.C.; Jeong, D.K.; Kim, K.H.; Nam, K.W.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, H.S.; Nam, S.B.; Bae, S.H. Adequacy of sentinel lymph node biopsy in malignant melanoma of the trunk and extremities: Clinical observations regarding prognosis. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2020, 47, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielin, O.; Van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Dummer, R.; Keilholz, U.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1884–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascinelli, N.; Belli, F.; Santinami, M.; Fait, V.; Testori, A.; Ruka, W.; Cavaliere, R.; Mozzillo, N.; Rossi, C.R.; MacKie, R.M.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, e498–e507. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, N.U.; Dogan, S.; Favero, G.; Köhler, C.; Dursun, P. The Basics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy: Anatomical and Patho-physiological Considerations and Clinical Aspects. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, D.E.; Patrascu, T.; Georgescu, T.F.; Tulin, A.; Mosoia, L.; Bacalbasa, N.; Stiru, O.; Georgescu, M.-T. Diabetes Mellitus as a Prognostic Factor for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. In Vivo 2021, 35, 2495–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, E.Z.; Gershenwald, J.E. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: Implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2018, 18, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemel, C.; Herrmann, K.; Giammarile, F.; Nieweg, O.E.; Dubreuil, J.; Testori, A.; Audisio, R.A.; Zoras, O.; Lassmann, M.; Chakera, A.H.; et al. EANM practice guidelines for lym-phoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, V.F.; Malloy, K.M. Sentinel Node Biopsy for Head and Neck Cutaneous Melanoma. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 54, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seim, N.B.; Wright, C.L.; Agrawal, A. Contemporary use of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the head and neck. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 2, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocan, D.; Barbe, C.; Aubin, F.; Granel-Brocard, F.; Lipsker, D.; Velten, M.; Dalac, S.; Truchetet, F.; Michel, C.; Mitschler, A.; et al. Distinctive Features of Melanoma and Its Man-agement in Elderly Patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobircă, A.; Bobircă, F.; Ancuta, I.; Florescu, A.; Pădureanu, V.; Florescu, D.; Pădureanu, R.; Florescu, A.; Mușetescu, A. Rheumatic Immune-Related Adverse Events—A Consequence of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Biology 2021, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, J.R.; Kang, S.; Balch, C.M. Melanoma in the Older Patient: Measuring Frailty as an Index of Survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 3531–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines for Patients Melanoma. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/melanoma-patient.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Kachare, S.D.; Brinkley, J.; Wong, J.H.; Vohra, N.A.; Zervos, E.E.; Fitzgerald, T.L. The Influence of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy on Survival for Intermediate-Thickness Melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 3377–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y. The Role and Necessity of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Invasive Melanoma. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faries, M.B.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; Andtbacka, R.H.; Mozzillo, N.; Zager, J.S.; Jahkola, T.; Bowles, T.L.; Testori, A.; Beitsch, P.D.; et al. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, S.J.; Perone, J.A.; Farrow, N.E.; Mosca, P.J.; Tyler, D.S.; Beasley, G.M. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Completion Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma. Curr. Treat Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffels, I.; Boy, C.; Pöppel, T.; Kuhn, J.; Klötgen, K.; Dissemond, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Klode, J. Association Between Sentinel Lymph Node Excision With or Without Preoperative SPECT/CT and Metastatic Node Detection and Disease-Free Survival in Melanoma. JAMA 2012, 308, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, N.S.; Brouwer, O.R.; Schaafsma, B.E.; Mathéron, H.M.; Klop, W.M.C.; Balm, A.J.; van Tinteren, H.; Nieweg, O.E.; van Leeuwen, F.W.; Valdés Olmos, R.A. Multimodal Surgical Guidance during Sentinel Node Biopsy for Melanoma: Combined Gamma Tracing and Fluorescence Imaging of the Sentinel Node through Use of the Hybrid Tracer Indocyanine Green– 99m Tc-Nanocolloid. Radiology 2015, 275, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, G.W.; Murray, D.R.; Thourani, V.; Hestley, A.; Cohen, C. The definition of the sentinel lymph node in melanoma based on radioactive counts. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2002, 9, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sharouni, M.A.; Witkamp, A.J.; Sigurdsson, V.; van Diest, P.J. Trends in Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Enactment for Cutaneous Melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliveres, E.S.; Marín, A.G.; Miralles, M.D.; Riera, C.N.; Gomis, A.C.; Gordon, M.M.; Leal, M.Á.A.; García, S.G. Sentinel Node Biopsy for Melanoma. Analysis of our Experience (125 Patients). Cirugía Española 2014, 92, 609–614. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaria, S.P.; Faries, M.B.; Morton, D.L. Sentinel node biopsy in melanoma: Technical considerations of the procedure as per-formed at the john wayne cancer institute. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 101, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, U.; Stadler, R.; Mauch, C.; Hohenberger, W.; Brockmeyer, N.; Berking, C.; Sunderkötter, C.; Kaatz, M.; Schulte, K.W.; Lehmann, P.; et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): A multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini-Spaltro, A.; Cappello, T.D.; Deluca, J.; Carriere, C.; Mazzoleni, G.; Eisendle, K. Melanoma incidence and Breslow tumour thickness development in the central Alpine region of South Tyrol from 1998 to 2012: A population-based study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melmar, T. Melanoma Margins Trial Investigating 1cm v 2cm Wide Excision Margins for Primary Cutaneous Melanoma (MelMarT). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02385214 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Moncrieff, M.D.; Gyorki, D.; Saw, R.; Spillane, A.J.; Peach, H.; Oudit, D.; Geh, J.; Dziewulski, P.; Wilson, E.; Matteucci, P.; et al. 1 Versus 2-cm Excision Margins for pT2-pT4 Primary Cutaneous Melanoma (MelMarT): A Feasibility Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, N.; Bertoglio, S.; Boscaneanu, A.; Minuto, M.; Reina, S.; Palombo, D.; Bruzzi, P.; Cafiero, F. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with malignant melanoma: Analysis of post-operative complications. ANZ J. Surg. 2019, 89, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, N.H.; Tian, J.; De Miera, E.V.-S.; Gold, H.; Darvishian, F.; Pavlick, A.C.; Berman, R.; Shapiro, R.L.; Polsky, D.; Osman, I. Impact of Age on the Management of Primary Melanoma Patients. Oncology 2013, 85, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, P.R.; Reymundo, A.; Delgado, Y. 33609 Factors associated with sentinel lymph node status in elderly melanoma pa-tients: A real practice cohort. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, AB60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grann, A.F.; Frøslev, T.; Olesen, A.B.; Schmidt, H.; Lash, T.L. The impact of comorbidity and stage on prognosis of Danish melanoma patients, 1987–2009: A registry-based cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Višnjić, A.; Kovačević, P.; Veličkov, A.; Stojanović, M.; Mladenović, S. Head and neck cutaneous melanoma: 5-year survival analysis in a Serbian university center. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejera-Vaquerizo, A.; Ribero, S.; Puig, S.; Boada, A.; Paradela, S.; Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Cañueto, J.; de Unamuno, B.; Brinca, A.; Descalzo-Gallego, M.A.; et al. Survival analysis and sentinel lymph node status in thin cutaneous melanoma: A multicenter observational study. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4235–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, A.; Zamfir-Chiru-Anton, A.; Stanciu, M.; Pantea-Stoian, A.; Nitipir, C.; Gheorghe, D. Serum melatonin is inversely asso-ciated with matrix metalloproteinase 9 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 13, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Rubatto, M.; Picciotto, F.; Moirano, G.; Fruttero, E.; Caliendo, V.; Borriello, S.; Sciamarrelli, N.; Fava, P.; Senetta, R.; Lesca, A.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Malignant Melanoma of the Head and Neck: A Single Center Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglino, P.; Ribero, S.; Osella-Abate, S.; Macrì, L.; Grassi, M.; Caliendo, V.; Asioli, S.; Sapino, A.; Macripò, G.; Savoia, P.; et al. Clinico-pathologic features of primary melanoma and sentinel lymph node predictive for non-sentinel lymph node involvement and overall survival in melanoma patients: A single centre observational cohort study. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 20, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghe, M.; Bordea, C.; Blidaru, A. Clinical significance of the lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of non-axillary sentinel lymph node localization in breast cancer. Chirurgia 2015, 110, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Voinea, S.; Sandru, A.; Gherghe, M.; Blidaru, A. Peculiarities of lymphatic drainage in cutaneous malignant melanoma: Clinical experience in 75 cases. Chirurgia 2014, 109, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mathelin, C.; Salvador, S.; Huss, D.; Guyonnet, J.-L. Precise Localization of Sentinel Lymph Nodes and Estimation of Their Depth Using a Prototype Intraoperative Mini -Camera in Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cohort Characteristics | N = 122 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) mean ± SD | 54.3 ± 14.4 |

| Lymph node removed n, % | |

| 1 | 84, 68.9% |

| >1 | 38, 31.1% |

| Positive SLN n, % | 30, 24.6% |

| Male n, % | 62, 50.8% |

| Menopause N = 60, n,% | 37, 61.6% |

| Melanoma site | |

| Head and neck n,% | 17, 13.9% |

| Thorax n,% | 39, 32.0% |

| Abdominal n,% | 18, 14.8% |

| Upper limbs n,% | 21, 17.2% |

| Lower limbs n,% | 27, 22.1% |

| pT3 and pT4 stage n,% | 61, 50.0% |

| Breslow index mean ± SD | 3.04 ± 2.8 |

| Oncological safety margins (mm) | |

| 1 | 35, 28.7% |

| 1.5 | 3, 2.5% |

| 2 | 84, 68.9% |

| Period from diagnosis to surgery (days) mean ± SD | 30.3 ± 5.1 |

| BRAF gene, N = 31 n,% | 22, 70.9% |

| History of cancer n,% | 5, 4.1% |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) mean ± SD | 24.1 ± 2.7 |

| Type anesthesia n,% | |

| Local | 30, 25.6% |

| General | 92, 75.4% |

| Cardiovascular diseases n,% | 39, 31.9% |

| Surgery complications n,% | 7, 5.7% |

| Surgery’s duration (min) mean ± SD | 125.0 ± 27.9 |

| Reintervention n,% | 2, 1.6% |

| Seroma n,% | 18, 14.8% |

| Prophylactic antibiotic therapy n,% | 119, 97.5% |

| Postoperative antibiotic therapy n,% | 119, 97.5% |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | 3.8 ± 1.4 |

| Preoperative anticoagulant therapy | 6, 4.9% |

| Preoperative antiaggregant therapy | 8, 6.6% |

| Switching anticoagulant therapy | 6, 4.9% |

| Wound healing (days) mean ± SD | 12.5 ± 1.9 |

| <70 Years Old | >=70 Years Old | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 97 | N = 25 | ||

| Lymph node removed n, % | 0.918 | ||

| 1 | 67, 69.1% | 17, 68.0% | |

| >1 | 30, 30.9% | 8, 32.0% | |

| Positive SLN n, % | 20, 20.6% | 10, 40.0% | 0.045 |

| Male n, % | 51, 52.6% | 11, 44.0% | 0.444 |

| Melanoma site | |||

| Head and neck n,% | 9, 9.3% | 8, 32.0% | 0.007 |

| Thorax, n,% | 33, 34.0% | 6, 24.0% | 0.338 |

| Abdominal n,% | 13, 13.4% | 5, 20.0% | 0.407 |

| Upper limbs n,% | 19, 19.6% | 2, 8.0% | 0.171 |

| Lower limbs n,% | 23, 23.7% | 4, 16.0% | 0.408 |

| pT3 and pT4 stage n,% | 44, 45.4% | 17, 68.0% | 0.044 |

| Breslow depth mean ± SD | 2.82 ± 2.5 | 3.88 ± 3.5 | 0.079 |

| Period from diagnosis to surgery (days) mean ± SD | 30.4 ± 5.1 | 29.9 ± 5.4 | 0.715 |

| BRAF gene, N = 31 n,% | 16 from 22 | 6 from 9 | 0.736 |

| History of cancer n,% | 4, 4.1% | 1, 4.0% | 1.000 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) mean ± SD | 20.21 ± 2.8 | 23.84 ± 2.7 | 0.536 |

| Type anesthesia n,% | 0.550 | ||

| Local | 25, 25.8% | 5, 20.0% | |

| General | 72, 74.2% | 20, 80.0% | |

| Cardiovascular diseases n,% | 22, 22.7% | 17, 68.0% | <0.001 |

| Surgery complications n,% | 2, 2.1% | 5, 20.0% | 0.004 |

| Surgery’s duration (min) mean ± SD | 123.30 ± 26.9 | 131.6 ± 31.4 | 0.082 |

| Reintervention n,% | 0 | 2, 8.0% | 0.041 |

| Seroma n,% | 12, 12.4% | 6, 24.0% | 0.202 |

| Postoperative antibiotic therapy n,% | 123.30 ± 26.9 | 131.6 ± 31.4 | 0.082 |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | 3.77 ± 1.4 | 3.84 ± 1.1 | 0.903 |

| Preoperative anticoagulant therapy | 1, 1.0% | 5, 20.0% | 0.001 |

| Preoperative antiaggregant therapy | 4, 4.1% | 4, 16.0% | 0.055 |

| Switching anticoagulant therapy | 1, 1.0% | 5, 20.0% | 0.001 |

| Wound healing (days) mean ± SD | 12.22 ± 1.8 | 13.48 ± 2.1 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bobircă, F.; Tebeică, T.; Pumnea, A.; Dumitrescu, D.; Alexandru, C.; Banciu, L.; Popa, I.L.; Bobircă, A.; Leventer, M.; Pătrașcu, T. The Characteristics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma and the Particularities for Elderly Patients—Experience of a Single Clinic. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13050926

Bobircă F, Tebeică T, Pumnea A, Dumitrescu D, Alexandru C, Banciu L, Popa IL, Bobircă A, Leventer M, Pătrașcu T. The Characteristics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma and the Particularities for Elderly Patients—Experience of a Single Clinic. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(5):926. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13050926

Chicago/Turabian StyleBobircă, Florin, Tiberiu Tebeică, Adela Pumnea, Dan Dumitrescu, Cristina Alexandru, Laura Banciu, Ionela Loredana Popa, Anca Bobircă, Mihaela Leventer, and Traian Pătrașcu. 2023. "The Characteristics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma and the Particularities for Elderly Patients—Experience of a Single Clinic" Diagnostics 13, no. 5: 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13050926

APA StyleBobircă, F., Tebeică, T., Pumnea, A., Dumitrescu, D., Alexandru, C., Banciu, L., Popa, I. L., Bobircă, A., Leventer, M., & Pătrașcu, T. (2023). The Characteristics of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma and the Particularities for Elderly Patients—Experience of a Single Clinic. Diagnostics, 13(5), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13050926