Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. State of Art

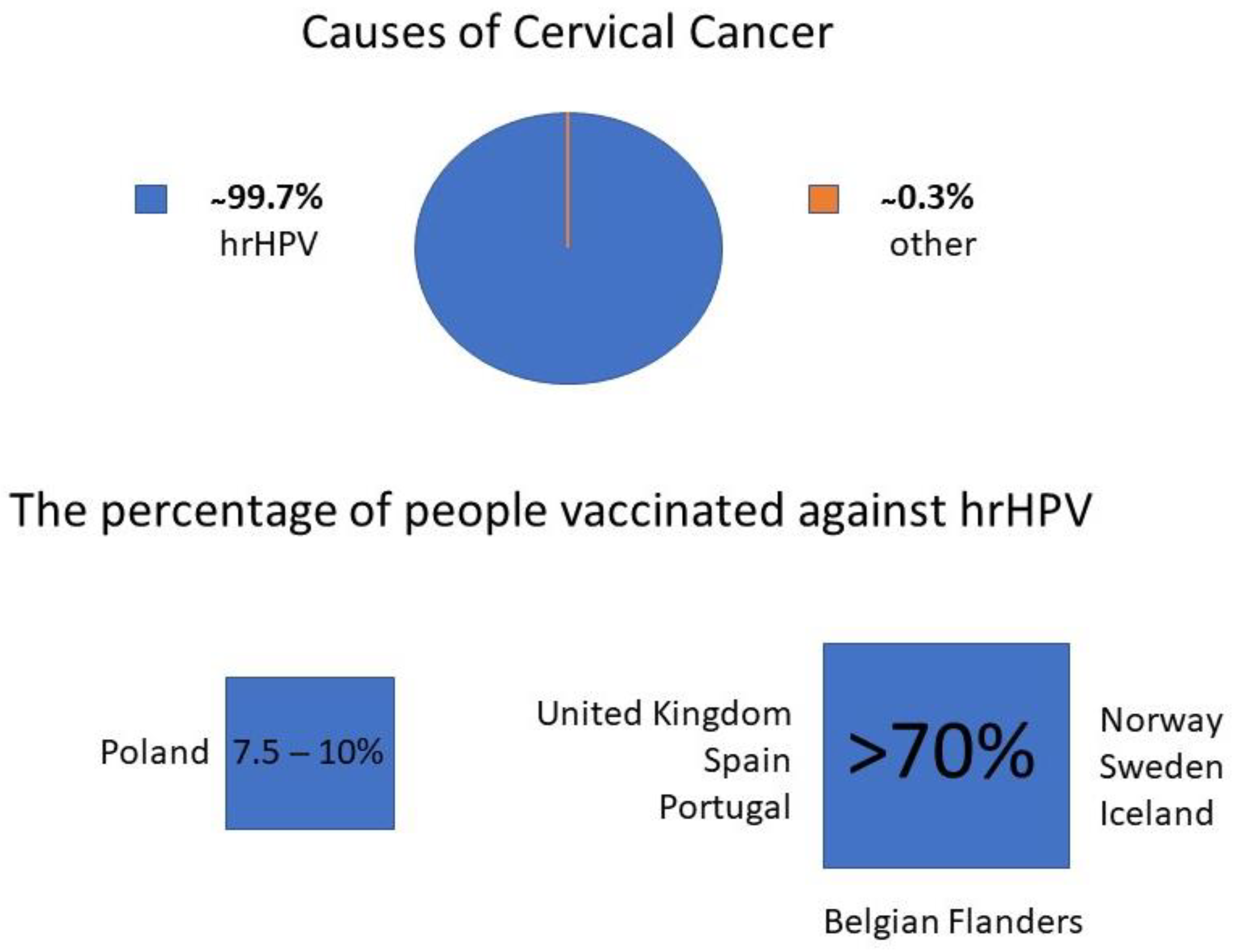

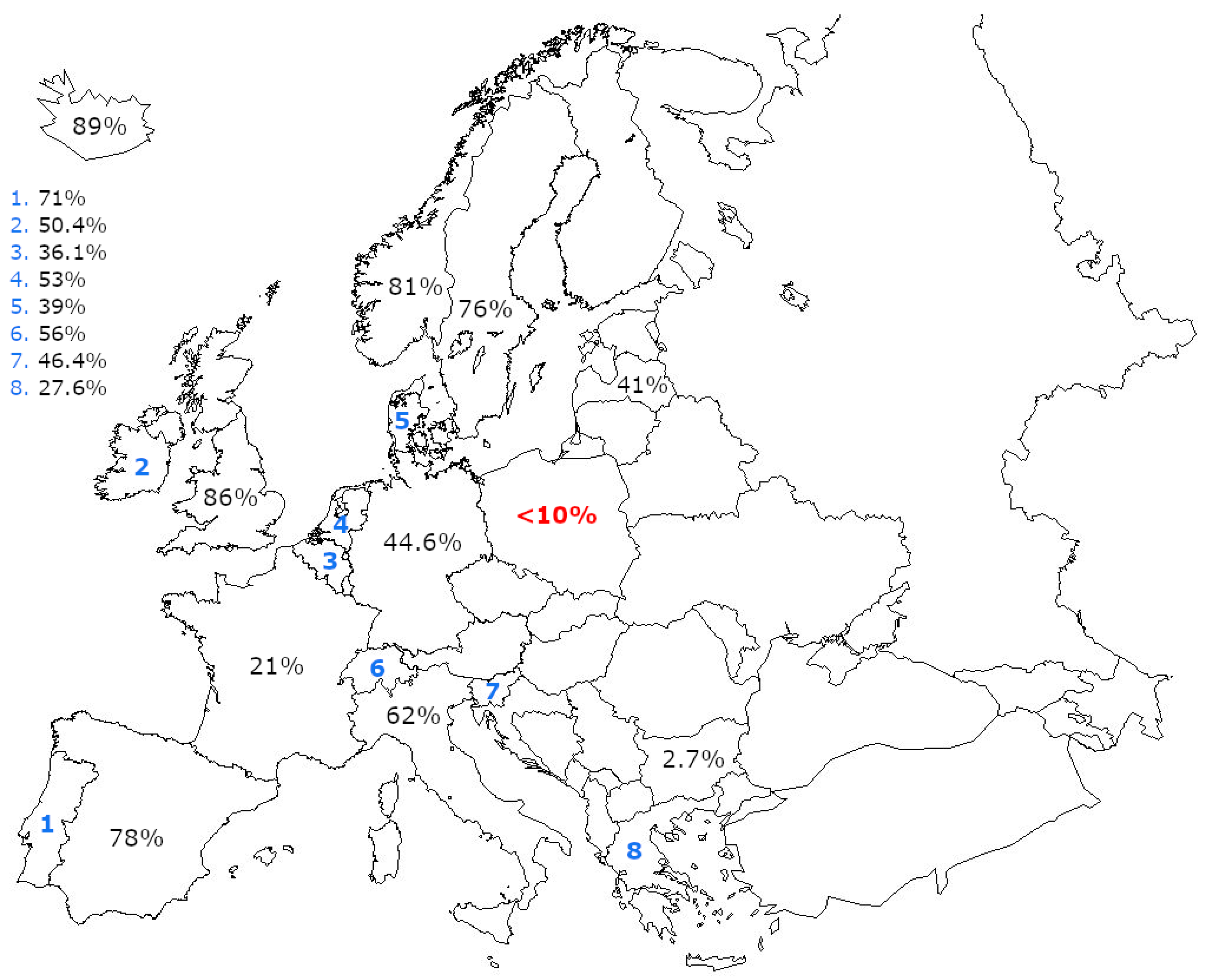

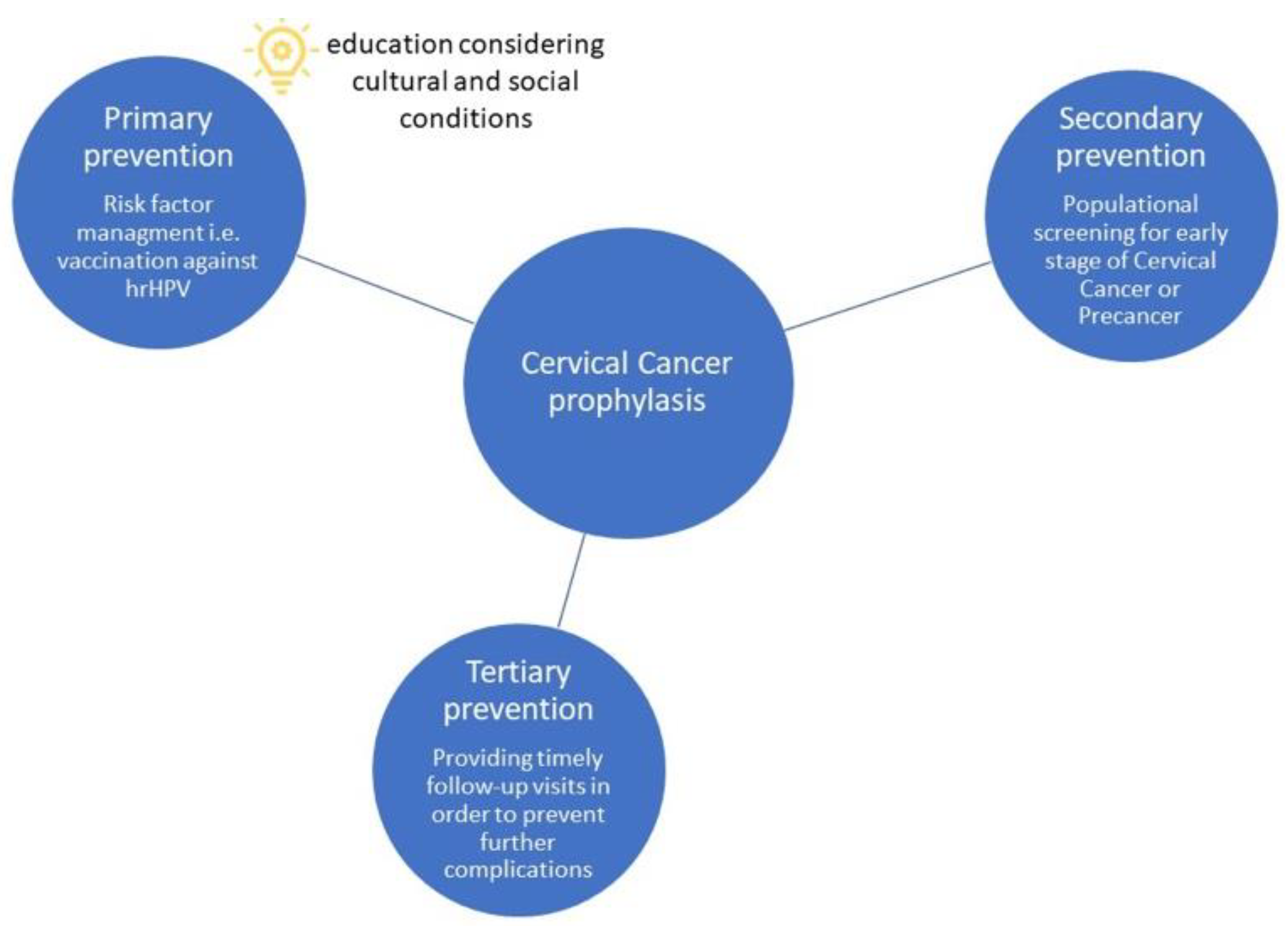

3.1.1. Primary Prevention

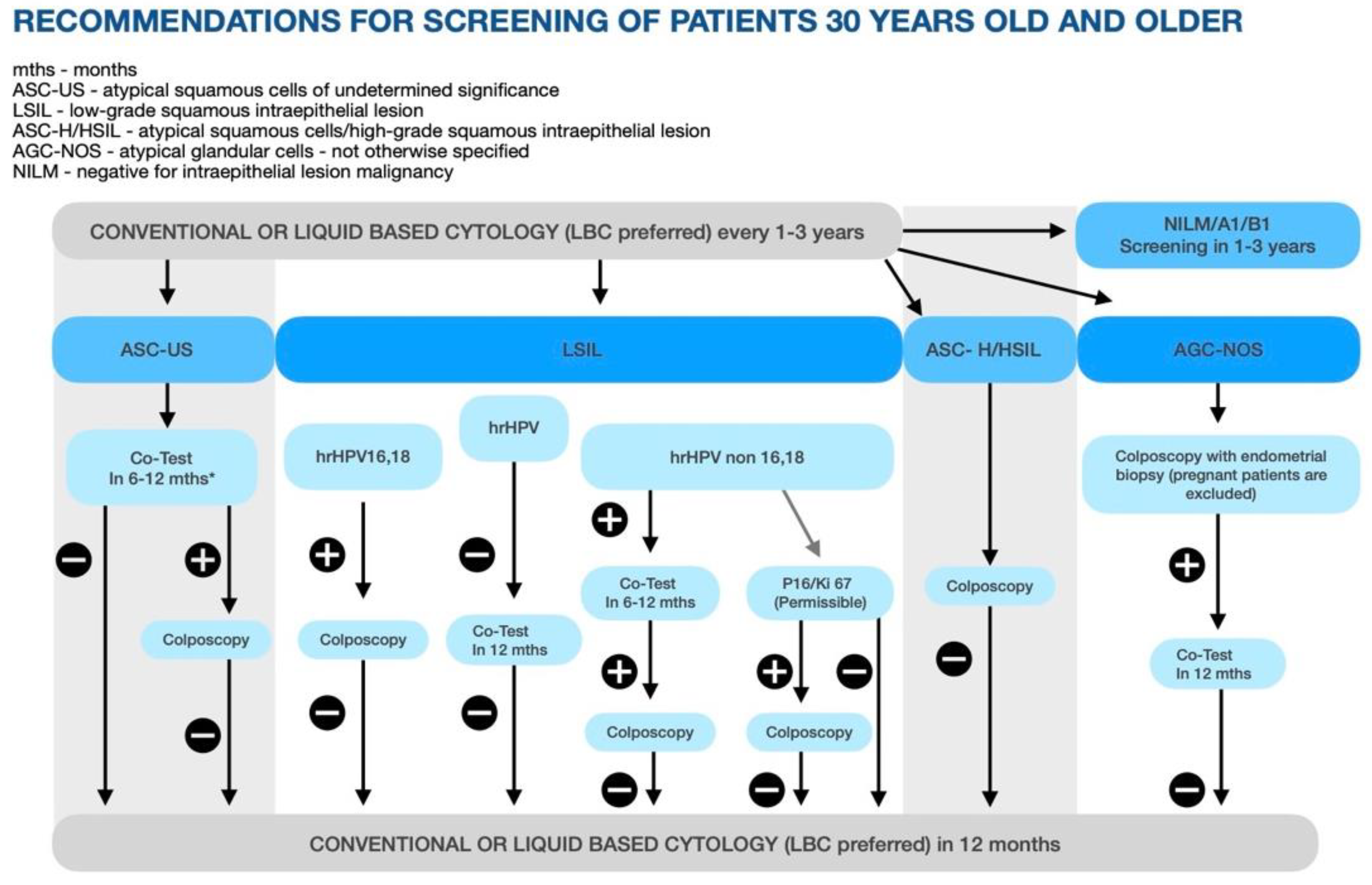

3.1.2. Secondary Prevention

3.1.3. Tertiary Prevention

3.2. Analysis of the Current Situation in Poland with Focus on Never Been Screened Persons

4. Discussion

- −

- Vaccination calendar—HPV vaccination as recommended and free.

- −

- Promoting vaccination in schools.

- −

- Involvement of the media (including actors and influencers) in promoting HPV vaccination.

- −

- Offering vaccinations to mothers who accompany patients in gynecological offices.

- −

- SMS notifications about cytology sent.

- −

- Mobile cervical cancer screening units (in case of itinerant shops, popular in Podlaskie and Lubelskie voivodships).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFI | Alliance for Innovation |

| AGC-NOS | Atypical Glandular Cells—not otherwise specified |

| AOTMiT | Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System |

| ASCC | American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology |

| ASCO | American Society for Clinical Oncology |

| CC | cervical cancer |

| CKC | cold knife conization |

| DDP | cisplatin |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ECC | endocervical curettage |

| FNAB | fine-needle aspiration biopsy |

| GP | general practitioners |

| GUS | Central Statistical Office (pol. Główny Urząd Statystyczny) |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HPV | human papilloma virus |

| hrHPV | high-risk human papilloma virus |

| IARC | Agency for Research on Cancer |

| LBC | liquid-based cytology |

| LEEP | loop electrosurgical excision procedure |

| LSIL | low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSCNRIO | Maria Sklodowska Curie National Research Institute |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NHF | National Health Fund (pol. NFZ) |

| NIK | Supreme Audit Office (pol. Najwyższa Izba Kontroli) |

| OS | overall survival |

| TSE | turbo spin echo imaging |

| US | United States |

| VIA | visual inspection with acetic acid |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, U.; Didkowska, J. Zachorowania i Zgony na Nowotwory Złośliwe w Polsce. Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów, Narodowy Instytut Onkologii im. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Available online: http://onkologia.org.pl/raporty/#tabela_rok (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Wojciechowska, U.; Didkowska, J. Changes in five-year relative survival rates in Poland in patients diagnosed in the years 1999–2010. Nowotwory. J. Oncol. 2017, 67, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arbyn, M.; Gultekin, M.; Morice, P.; Nieminen, P.; Cruickshank, M.; Poortmans, P.; Kelly, D.; Poljak, M.; Bergeron, C.; Ritchie, D.; et al. The European response to the WHO call to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walboomers, J.M.M.; Jacobs, M.V.; Manos, M.M.; Bosch, F.X.; Kummer, J.A.; Shah, K.V.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Muñoz, N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999, 189, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, S.K.; Dehlendorff, C.; Belmonte, F.; Baandrup, L. Real-World Effectiveness of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Against Cervical Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsianka, B.; Gańczak, M. Evaluation of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination strategies and vaccination coverage in adolescent girls worldwide. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2015, 69, 53–155. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Huu, N.; Thilly, N.; Derrough, T.; Sdona, E.; Claudot, F.; Pulcini, C.; Agrinier, N. HPV Policy working group. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage, policies, and practical implementation across Europe. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, N.J.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Kenter, G.G.; Berkhof, J.; Meijer, C.J.L.M. HPV-based cervical screening: Rationale, expectations and future perspectives of the new Dutch screening programme. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2019. Beyond Income, beyond Averages, beyond Today: Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2019 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Poniewierza, P.; Śniadecki, M.; Brzeziński, M.; Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Panek, G. Secondary prevention and treatment of cervical cancer—An update from Poland. Nowotwory J. Oncol. 2022, 1, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego. Szczepionka Przeciw HPV. Available online: https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/szczepionki/hpv/?strona=4#jakie-rodzaje-szczepionek-sa-dostepne-w-polsce (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Informacja Ministra Zdrowia w Sprawie Włączenia do Wykazu Refundowanych Leków Szczepionki Przeciw Wirusowi Brodawczaka Ludzkiego (HPV) Oraz Zmian w e-Karcie Szczepień. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/informacja-ministra-zdrowia-w-sprawie-wlaczenia-do-wykazu-refundowanych-lekow-szczepionki-przeciw-wirusowi-brodawczaka-ludzkiego-hpv-oraz-zmian-w-e-karcie-szczepien?fbclid=IwAR0YW7pPTQztiqzfrCc9yrAX7KBY0IVoGTGxFGEmOt90iBbPJ (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Wojtyła, C.; Ciebiera, M.; Kowalczyk, D.; Panek, G. Cervical Cancer Mortality in East-Central European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, G.; Nakisige, C.; Huh, W.K.; Mehrotra, R.; Franco, E.L.; Jeronimo, J. Optimizing secondary prevention of cervical cancer: Recent advances and future challenges. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 138, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/144785/9789241548953_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Zimmer, M.; Bidziński, M.; Czajkowski, K.; Wielgoś, M.; Sawicki, W.; Sieroszewski, P.; Oszukowski, P.; Stojko, R.; Pityński, K.; Paszkowski, T.; et al. Schemat postępowania w skriningu raka szyjki macicy Polskiego Towarzystwa Ginekologów i Położników (PTGiP)—Wersja grudzień 2021 r. Ginekol. I Perinatol. Prakt. 2021, 6, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control: A Healthier Future for Girls and Women. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/78128/9789241505147_eng.pdf;jsessionid=00AD6628CB0BCBF08B022A9E8097BBF0?sequence=3 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Jin, J.; Sklar, G.E.; Oh, V.N.S.; Li, S.C. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, R. Impact of physician-patient communication in online health communities on patient compliance: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairkhah, N.; Bolhassani, A.; Najafipour, R. Current and future direction in treatment of HPV-related cervical disease. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 100, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowska-Durawa, A.; Luszczynska, A. Badania przesiewowe w kierunku raka szyjki macicy a bariery psychospołeczne postrzegane przez pacjentki. Przegląd systematyczny. Contemp. Oncol. 2014, 18, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Najwyższa Izba Kontroli. Wiejska Droga do Ginekologa. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/aktualnosci/wiejska-droga-do-ginekologa.html (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Dulak, M.; Jakubowski, B. Publiczny Transport Zbiorowy w Polsce. Studium Upadku. Available online: https://klubjagiellonski.pl/2018/04/17/publiczny-transport-zbiorowy-w-polsce-studium-upadku/ (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Valanis, B.G.; Glasgow, R.E.; Mullooly, J.; Vogt, T.M.; Whitlock, E.P.; Boles, S.M.; Smith, K.S.; Kimes, T.M. Screening HMO women overdue for both mammograms and Pap tests. Prev. Med. 2002, 34, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luszczynska, A.; Goc, G.; Scholz, U.; Kowalska, M.; Knoll, N. Enhancing intentions to attend cervical cancer screening with a stage-matched intervention. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, M.C.; Clark, M.A.; Rogers, M.L.; McGarry, K.; Sciamanna, C.N. Patient-Provider Communication and Cancer Screening among Unmarried Women. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 73, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaczyński, M.; Nowak-Markwitz, E.; Januszek-Michalecka, L.; Karowicz-Bilińska, A. Profil socjalny kobiet a ich udział w Programie Profilaktyki i Wczesnego Wykrywania Raka Szyjki Macicy w Polsce. Ginekol. Pol. 2009, 80, 833–838. [Google Scholar]

- Chorley, A.J.; Marlow, L.A.V.; Forster, A.S.; Haddrell, J.B.; Waller, J. Experiences of cervical screening and barriers to participation in the context of an organised programme: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomized controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532, Erratum in Lancet 2015, 386, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypień, P.; Zielonka, T.M. HPV infections, related diseases and prevention methods. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2022, 24, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.T.; Simms, K.T.; Lew, J.; Smith, M.A.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Saville, M.; Frazer, I.H.; Canfell, K. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e19–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cancer Council Australia Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Party. National Cervical Screening Program: Guidelines for the Management of Screen-Detected Abnormalities, Screening in Specific Populations and Investigation of Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding. Available online: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Cervical_cancer/Screening (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Sjukdomsinformation om HPV-Infektion. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/smittsamma-sjukdomar/hpv-infektion/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- WHO Call. Global Strategy Towards the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Jeronimo, J.; Castle, P.E.; Temin, S.; Denny, L.; Gupta, V.; Kim, J.J.; Luciani, S.; Murokora, D.; Ngoma, T.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Secondary prevention of cervical cancer: ASCO resource-stratified clinical practice guideline. J. Glob. Oncol. 2016, 3, 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, W.K.; Ault, K.A.; Chelmow, D.; Davey, D.D.; Goulart, R.A.; Garcia, F.A.R.; Kinney, W.K.; Massad, L.S.; Mayeaux, E.J.; Saslow, D.; et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: Interim clinical guidance. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 136, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jach, R.; Mazurec, M.; Trzeszcz, M.; Zimmer, M.; Kedzia, W.; Wolski, H. Cervical cancer screening in Poland in current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Interim guidelines of the Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians and the Polish Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathophysiology—A summary January 2021. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, S.D. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening in high incidence populations: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Women Health 2016, 56, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, D.; Keung, M.H.T.; Huang, Y.; McDermott, T.L.; Romano, J.; Saville, M.; Brotherton, J.M.L. Self-Collection for Cervical Screening Programs: From Research to Reality. Cancers 2020, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J. Eradicating cervical cancer: Lessons learned from Rwanda and Australia. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 154, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frett, B.; Aquino, M.; Fatil, M.; Seay, J.; Trevil, D.; Fièvre, M.J.; Kobetz, E. Get Vaccinated! and Get Tested! Developing Primary and Secondary Cervical Cancer Prevention Videos for a Haitian Kreyòl-Speaking Audience. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Poland Edition: Cervical Cancer. Version 1.2021—22 October 2021. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/login?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical-poland.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Profilaktyka Raka Szyjki Macicy|Pacjent. (14 November 2019). Available online: https://pacjent.gov.pl/program-profilaktyczny/profilaktyka-raka-szyjki-macicy (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Szczepienia.Info. Available online: https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/szczepionki/hpv/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Nowakowski, A.; Turkot, M.; Miłosz, K. Should we continue population-based cervical cancer screening programme in Poland? A statement in favour. Nowotwory J. Oncol. 2018, 68, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Śniadecki, M.; Poniewierza, P.; Jaworek, P.; Szymańczyk, A.; Andersson, G.; Stasiak, M.; Brzeziński, M.; Bońkowska, M.; Krajewska, M.; Konarzewska, J.; et al. Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12081807

Śniadecki M, Poniewierza P, Jaworek P, Szymańczyk A, Andersson G, Stasiak M, Brzeziński M, Bońkowska M, Krajewska M, Konarzewska J, et al. Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(8):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12081807

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚniadecki, Marcin, Patryk Poniewierza, Paulina Jaworek, Ada Szymańczyk, Gorm Andersson, Maria Stasiak, Michał Brzeziński, Małgorzata Bońkowska, Magdalena Krajewska, Joanna Konarzewska, and et al. 2022. "Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities" Diagnostics 12, no. 8: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12081807

APA StyleŚniadecki, M., Poniewierza, P., Jaworek, P., Szymańczyk, A., Andersson, G., Stasiak, M., Brzeziński, M., Bońkowska, M., Krajewska, M., Konarzewska, J., Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D., Guzik, P., & Wydra, D. G. (2022). Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities. Diagnostics, 12(8), 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12081807