Cervical Power Doppler Angiography with Micro Vessel Blood Flow Indices in the Auxiliary Diagnosis of Acute Cervicitis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Transvaginal Ultrasound with Power Doppler Angiography (TV-PDA)

2.3. Measurement of Blood Flow Velocity Waveforms within the Uterine Cervix

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

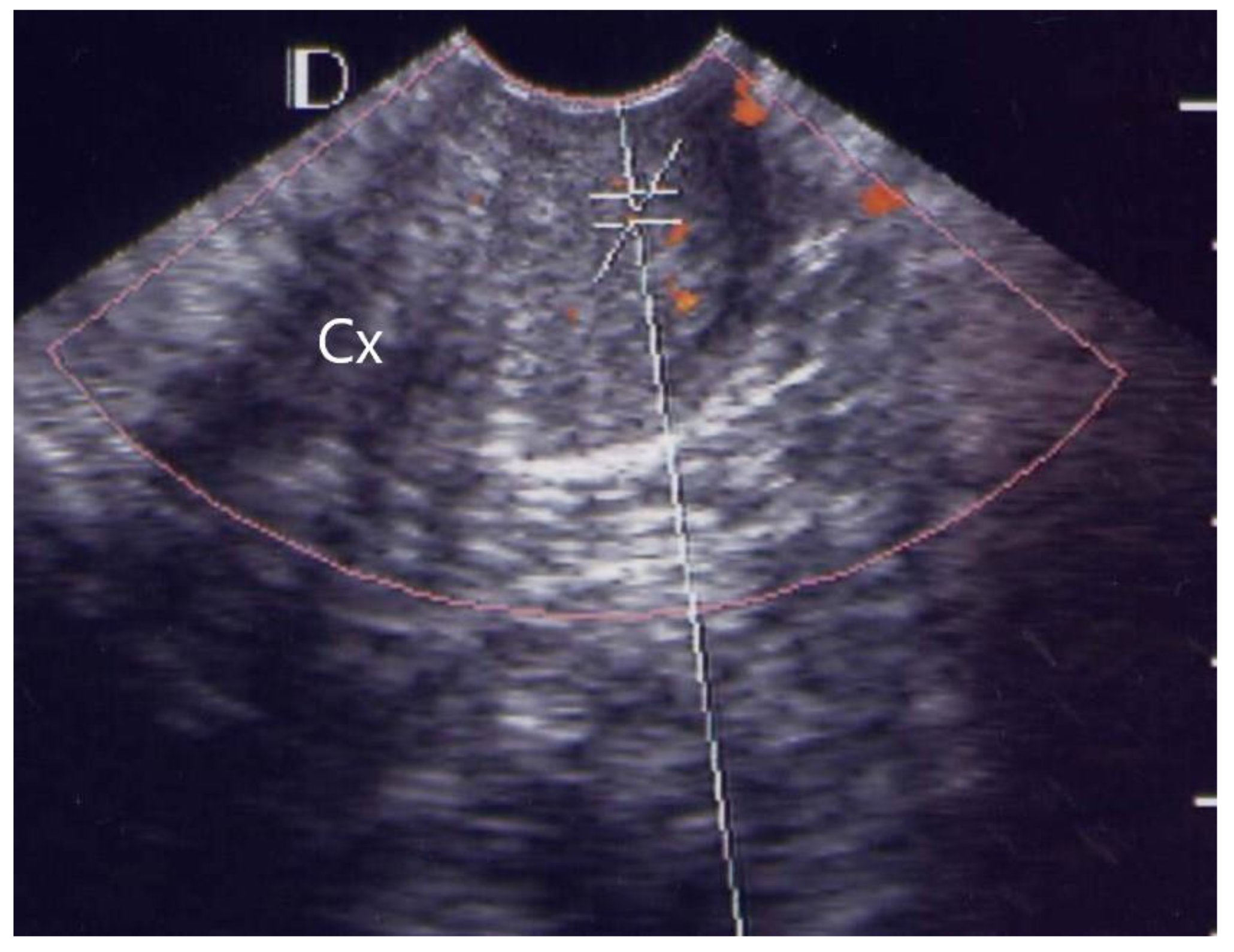

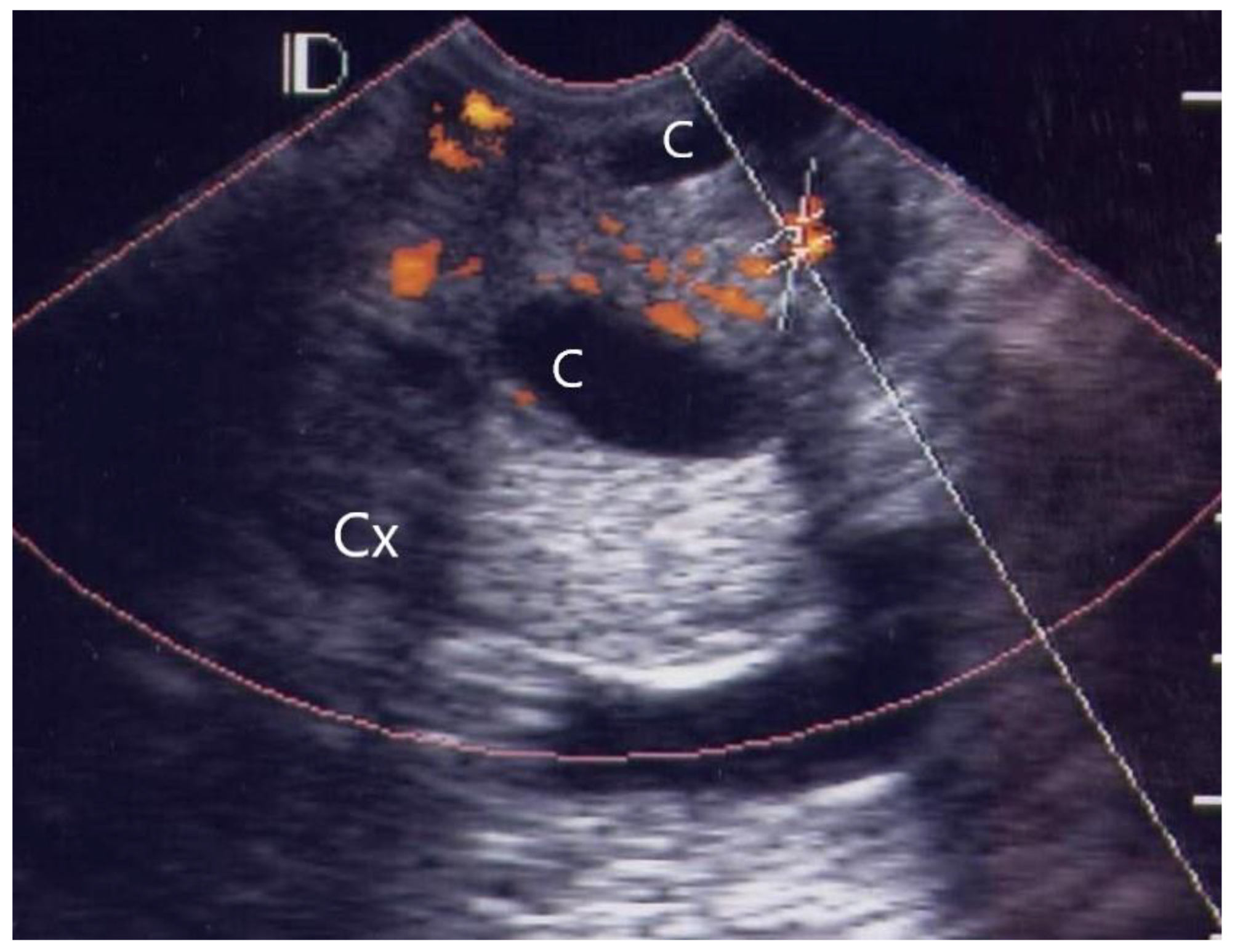

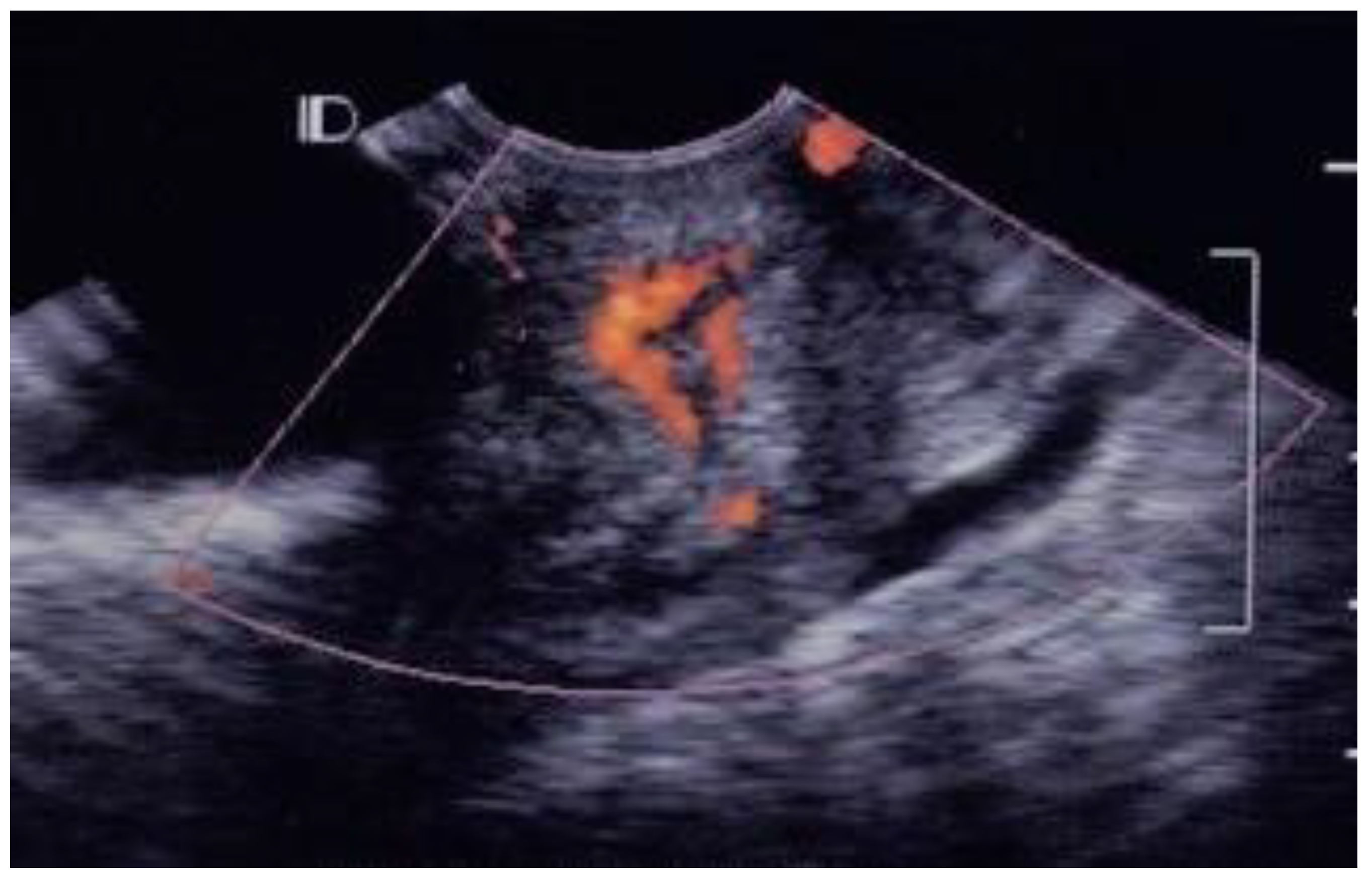

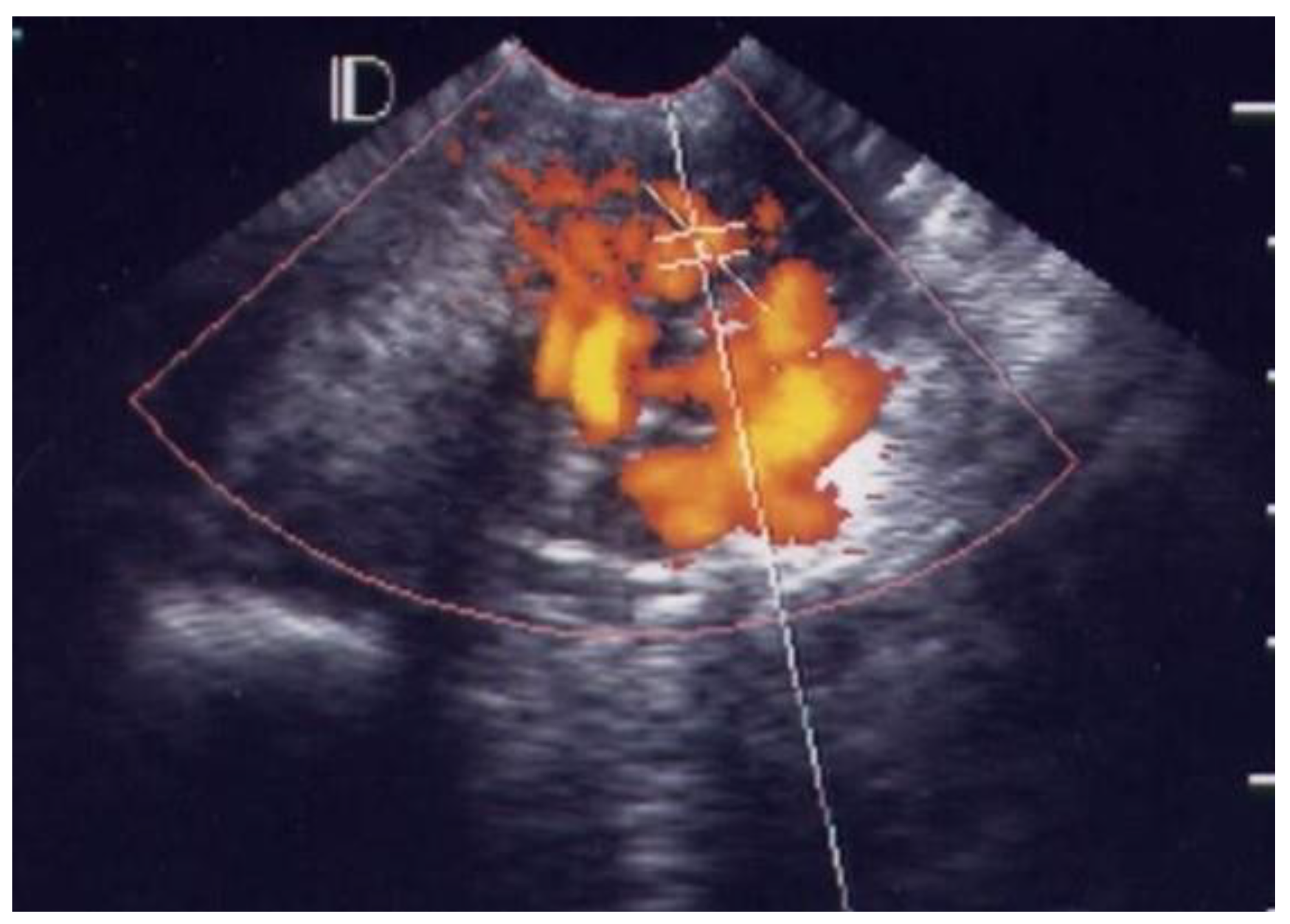

3.1. Visual Grading of Vascularity Findings on TV-PDU

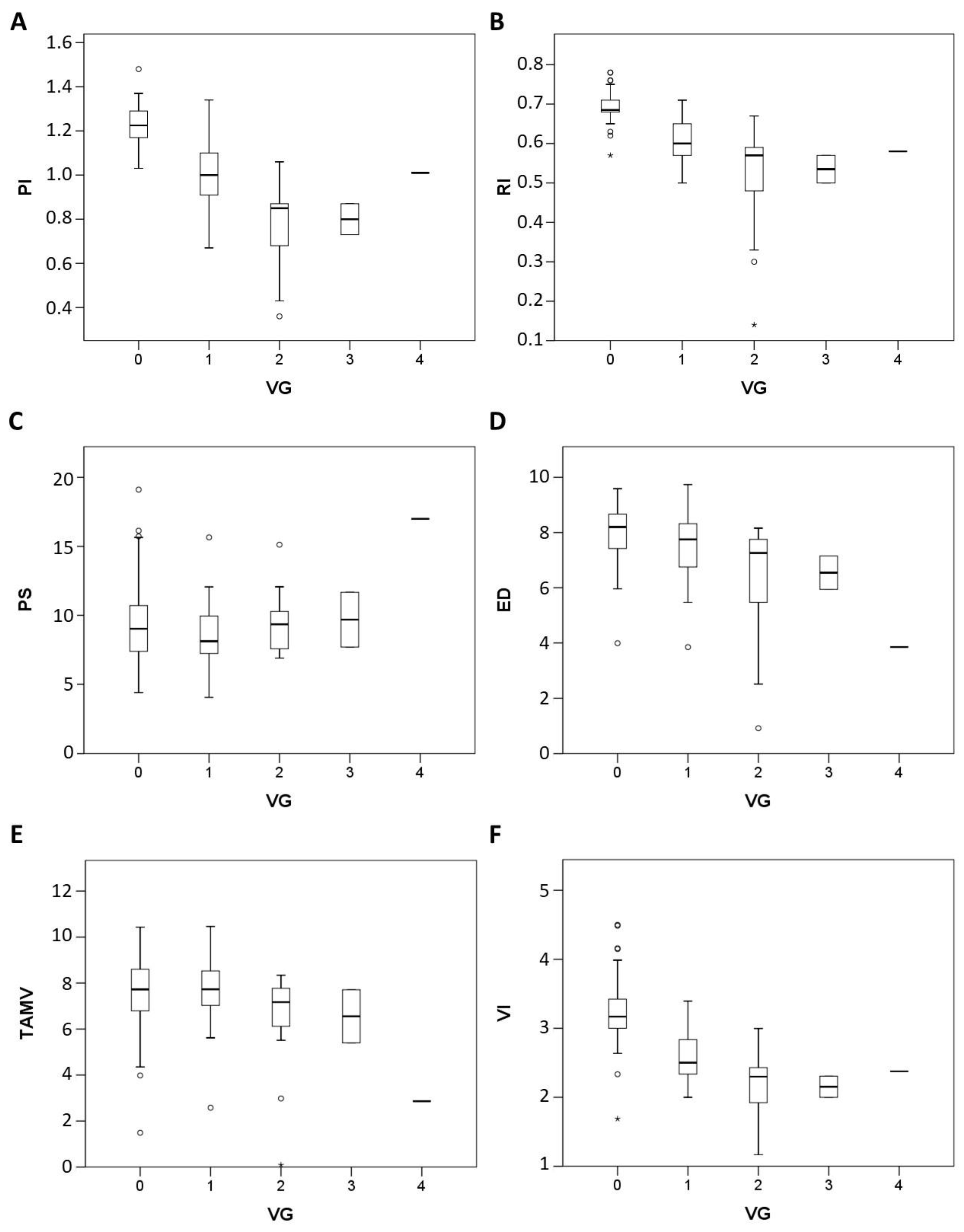

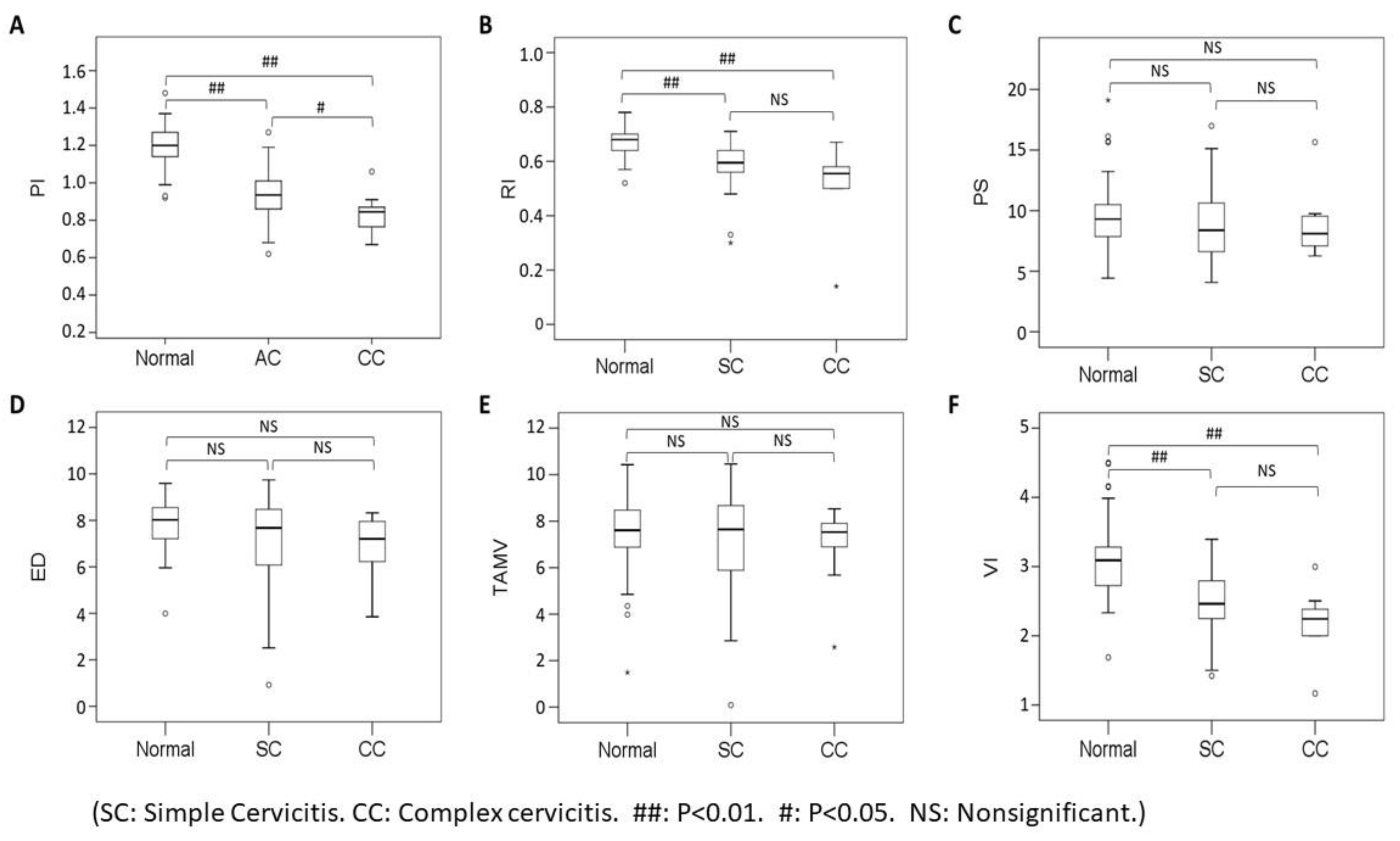

3.2. Micro-vessel Flow Velocity Waveform Findings on TV-PDU

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kupestic, S.; Kurjak, A.; Pasalic, L.; Benic, S.; Iljas, M. The value of transvaginal color Doppler in the assessment of pelvic inflammatory disease. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1995, 21, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatas, C.; Aksoy, E.; Akarsu, C.; Yakin, K.; Bahceci, M. Hemodynamic assessment in pelvic inflammatory disease by transvaginal color Doppler ultrasonography. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 70, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkanen, H.; Kujansuu, E. Doppler ultrasound findings in tubo-ovarian infectious complex. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1993, 21, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunato, S.J. The use of power Doppler and color power angiography in fetal imaging. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 174, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Yuan, C.C.; Hung, J.H.; Chao, K.C.; Yen, M.S.; Ng, H.T. Power Doppler angiographic appearance and blood flow velocity waveforms in invasive cervical carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 79, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurjak, A.; Zalud, I.; Jurkovic, D.; Alfirevic, Z.; Miljan, M. Transvaginal color flow Doppler for the assessment of pelvic circulation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1989, 68, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Tsui, K.H.; Hung, J.H.; Yuan, C.C.; Ng, H.T. High-frequency power Doppler angiographic appearance and microvascular flow velocity in recurrent scar endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 21, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Yang, H.J.; Yuan, C.C.; Chao, K.C. Visual grading system, blood flow index, and tumor marker SCC antigen as prognostic factors in invasive cervical carcinoma. J. Med. Ultrasound 2006, 14, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molander, P.; Sjoberg, J.; Paavonen, J.; Cacciatore, B. Transvaginal power Doppler findings in laparoscopically proven acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 17, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romosan, G.; Bjartling, C.; Skoog, L.; Valentin, L. Ultrasound for diagnosing acute salpingitis: A prospective observational diagnostic study. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romosan, G.; Valentin, L. The sensitivity and specificity of transvaginal ultrasound with regard to acute pelvic inflammatory disease: A review of the literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbay, K.; Deveci, S. Relationships between transvaginal colour Doppler findings, infectious parameters, and visual analogue scale scores in patients with mild acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 156, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, R.; Aviram, R.; Cohen, N.; Cohen, I.; Holtzinger, M.; Beyth, Y. Doppler flow characteristic in patients with pelvic inflammatory disease: Responders versus non-responders to therapy. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1998, 26, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suren, A.; Osmers, R.; Kuhn, W. 3D Color Power Angio TM imaging: A new method to assess intracervical vascularization in benign and pathological conditions. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 11, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, A.C.; Ferrandina, G.; Distefano, M.; Fruscella, E.; Mansueto, D.; Basso, D.; Salutari, V.; Scambia, G. Color Doppler velocimetry and three-dimensional color power angiography of cervical carcinoma. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 24, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovas, L.; Sladjevicius, P.; Strobel, E.; Valentin, L. Intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility of three-dimensional grayscale and power Doppler ultrasound examinations of the cervix in pregnant women. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 26, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basgul, A.; Kavak, Z.N.; Bakirci, N.; Gokaslan, H. Three-dimensional ultrasound power Doppler assessment of the cervix: Comparison between nulliparas and multiparas. J. Perinat. Med. 2007, 35, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esin, S.; Yirci, B.; Yalvac, S.; Kandemir, O. Use of translabial three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound for cervical assessment before labor induction. J. Perinat. Med. 2017, 45, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataganara, T.; Yapan, P.; Moungmaithong, S.; Sompagdee, N.; Phithakwatchara, N.; Limsiri, P.; Nawapun, K.; Rekhawasin, T.; Talungchit, P. Additional benefits of three-dimensional ultrasound for prenatal assessment of twins. J. Perinat. Med. 2020, 48, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Shi, G.; Qi, Z.; Zheng, J.; Chen, S. Advancements in the application of ultrasound elastography in the cervix. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 2048–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltovich, H.; Carlson, L. New techniques in evaluation of the cervix. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.C.; Hall, T.J.; Rosado-Mendez, I.M.; Palmeri, M.L.; Feltovich, H. Detection of changes in cervical softness using shear wave speed in early versus late pregnancy: An in vivo cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018, 44, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Number | Vascular Hot Spot Grading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | ||

| Simple Cervicitis | 26 | 0 | 19 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Complex Cervicitis | 12 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + TOA | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + PCS | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + PCO | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + RO | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + BC | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + ROC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cervicitis + TOA+ OC | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal Cervix | 41 | 30 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Grading | Numbers of Vascular Hot Spot within Cervix (One Spot: 1 × 1 mm) |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Absence of vascular hot spot |

| Grade 1 | <5 vascular spots, not involve the endocervical canal |

| Grade 2 | >5 vascular spots, not involve the endocervical canal |

| Grade 3 | Involved the endocervical canal, without involved whole endocervix |

| Grade 4 | Involved the whole endocervix |

| A: Optimal Cutoff of Six Sonographic Parameters for Discriminating Acute Cervicitis Group (N = 38) with Control Group (N = 41) | ||||||||

| Area under the Curve | ||||||||

| Variables | Area | Optimal | Sensitivity | 95%LCL | 95%UCL | Specificity | 95%LCL | 95%UCL |

| PI | 0.93 | 1.1 | 92.1 | 78.6 | 98.3 | 85.4 | 70.8 | 94.4 |

| RI | 0.86 | 0.6 | 78.9 | 62.7 | 90.4 | 85.4 | 70.8 | 94.4 |

| PS | 0.59 | 8.5 | 50 | 33.3 | 66.6 | 56.1 | 39.7 | 71.5 |

| ED | 0.64 | 3.1 | 65.8 | 48.6 | 80.4 | 58.5 | 42.1 | 73.7 |

| TAMV | 0.54 | 5.2 | 60.5 | 43.4 | 75.9 | 46.3 | 30.7 | 62.6 |

| VI | 0.85 | 2.6 | 78.9 | 62.7 | 90.4 | 85.4 | 70.8 | 94.4 |

| B: Optimal Cutoff of Six Sonographic Parameters for Discriminating Complex Cervicitis Group (N = 12) with Simple Cervicitis Group (N = 26) | ||||||||

| Area under the Curve | ||||||||

| Variables | Area | Optimal | Sensitivity | 95%LCL | 95%UCL | Specificity | 95%LCL | 95%UCL |

| PI | 0.74 | 0.9 | 83.3 | 51.6 | 97.9 | 69.2 | 48.2 | 85.7 |

| RI | 0.69 | 0.6 | 75 | 42.8 | 94.5 | 65.4 | 44.3 | 82.8 |

| PS | 0.55 | 8.6 | 66.7 | 34.9 | 90 | 50 | 29.9 | 70.1 |

| ED | 0.58 | 3.3 | 75 | 42.8 | 94.5 | 46.2 | 26.6 | 66.6 |

| TAMV | 0.54 | 5.4 | 50 | 21.1 | 78.9 | 50 | 29.9 | 70.1 |

| VI | 0.69 | 2.4 | 75 | 42.8 | 94.5 | 65.4 | 44.3 | 82.8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-H.; Ko, Y.-L.; Huang, J.Y.-J.; Yuan, C.-C.; Wang, P.-H.; Hsiao, C.-H.; Chu, W.-C. Cervical Power Doppler Angiography with Micro Vessel Blood Flow Indices in the Auxiliary Diagnosis of Acute Cervicitis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12051131

Wu Y-C, Chen C-H, Ko Y-L, Huang JY-J, Yuan C-C, Wang P-H, Hsiao C-H, Chu W-C. Cervical Power Doppler Angiography with Micro Vessel Blood Flow Indices in the Auxiliary Diagnosis of Acute Cervicitis. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(5):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12051131

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yi-Cheng, Ching-Hsuan Chen, Yi-Li Ko, Jack Yu-Jen Huang, Chiou-Chung Yuan, Peng-Hui Wang, Ching-Hua Hsiao, and Woei-Chyn Chu. 2022. "Cervical Power Doppler Angiography with Micro Vessel Blood Flow Indices in the Auxiliary Diagnosis of Acute Cervicitis" Diagnostics 12, no. 5: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12051131

APA StyleWu, Y.-C., Chen, C.-H., Ko, Y.-L., Huang, J. Y.-J., Yuan, C.-C., Wang, P.-H., Hsiao, C.-H., & Chu, W.-C. (2022). Cervical Power Doppler Angiography with Micro Vessel Blood Flow Indices in the Auxiliary Diagnosis of Acute Cervicitis. Diagnostics, 12(5), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12051131