A New Screening Tool for Rapid Diagnosis of Functional and Environmental Factors Influencing Adults with Intellectual Disabilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS) [17];

- (2)

- The Rapid Assessment for Developmental Disabilities, Second Edition (RADD-2);

- (3)

- (4)

Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Setting

Changes during COVID-19 and after (September 2020–June 2022)

2.4. Materials

Functional Screening Tool for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities (FST-ID)

2.5. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Use of Assistive Devices

3.2. Phase One: Psychometric Values of the New Tool (FST-ID) (September 2019–September 2020)

3.3. Phase Two: Using the FST ID during 22 Months of the Pandemic (September 2020–June 2022)

3.3.1. Functional Changes for 76 Adults with ID

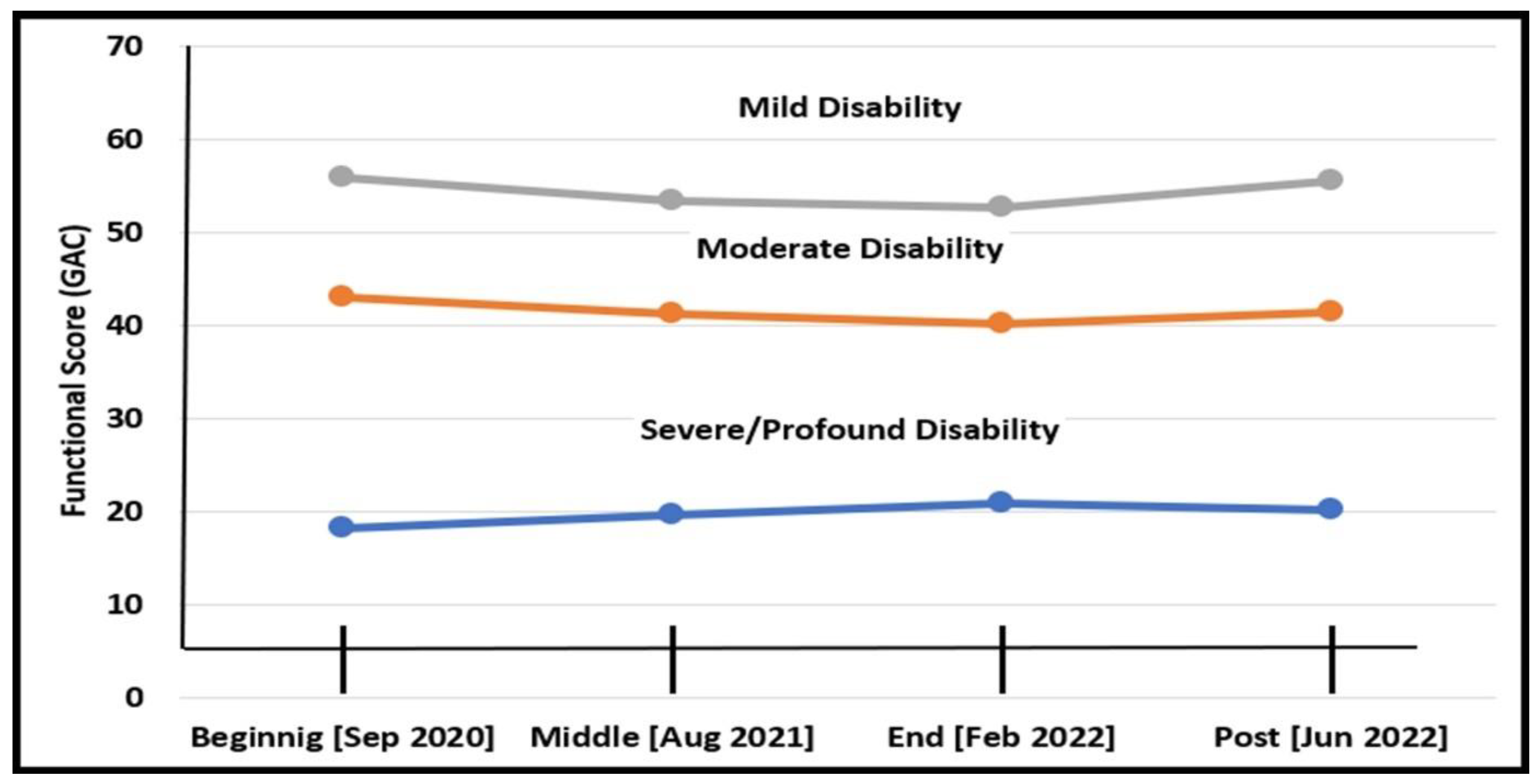

3.3.2. Functional Changes According to Disability Level

3.3.3. Functional Changes According to Type of Day-Care

3.3.4. Functional Changes According to Type of Residence

3.3.5. Environmental Changes for 76 Adults with ID

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Communications and Academics (CON) | Score |

|---|---|

| Communications: communicates well with everyone (4), communicates reasonably well with some people (3), maintains limited communication with few people (2), rarely communicates with the human environment (1), does not seem to communicate (0). | |

| Language and speech: fluent and coherent (4), short but clearly understandable sentences (3), most speech is not clear (2), single words, many unclear (1), does not seem to speak at all (0). | |

| Writing (by hand or with the assistance of a switch, a spelling board, etc.): complete, entire stories (4), writes sentences (3), writes words (2), copies few words or letters (1), does not write (0). | |

| Comprehension: understands everything (4), understands daily/related issues (3), understands most instructions (2), understands few/basic instructions (1), does not understand instructions (0). | |

| Reading: reads short stories (4), reads short sentences (3), reads at least 5 words (2), identifies letters (1), not able to read (0). | |

| Practical activities of daily living (ADL) and self-care | |

| Mobility: walks, sits, and lies down independently (4), is mostly independent but uses walker or wheelchair (3), needs mild supervision in transitions (2), needs extensive support in transitions (1), needs complete support in all ADL (0). | |

| Falls: Walks independently without any falls in the past year (4), lost their balance last year but did not fall (3), fell several times this year (2), fell several times this week (1), needs constant support/supervision to prevent falls (0). | |

| Daily activities (preparing a beverage, organizing a desk or classroom, throwing out the garbage, putting things back in their place): completely independent (4), needs mild supervision and verbal direction during ADL (3), need physical assistance in a small number of activities (2), needs assistance in most activities (1), needs full support to perform these activities at all (0). | |

| Leisure activities (draws, flips pages through a newspaper, strings beads, plants a plant): completely independent (4), needs only supervision and light verbal direction (3), needs a little physical and mostly verbal support (2), needs extensive physical & verbal support to participate (1), is unable to perform these activities at all (0). | |

| Eating and drinking: independent (4), needs food to be cut (3), needs mild assistance and/or mostly independent with special cutlery (2), needs to be fed completely (1), enteral feeding only (0). | |

| Food consistency: ordinary (4), cut into small pieces (3), chopped (2), blended (1), food blended and beverage with thickening agent (0). | |

| Mealtime behavior: ordinary (4), mild supervision only (3), custom eating environment and group supervision (2), staff member provides personal supervision due to challenges (1), does not eat in the setting (0). | |

| Toileting: completely independent (4), independent but needs verbal reminders (3), needs assistance only in wiping or during menstrual period (2); partial control of urination or soiling (may alert caregiver) (1), no control at all/wears diapers continuously (0). | |

| Dressing: completely independent (4), needs mild assistance (mostly verbal) (3), needs moderate assistance (with shoelaces, buttons, and zippers) (2), mostly not independent (1), does not dress independently (0). | |

| Self-care and hygiene (washes hands, awareness of deodorant, menstrual products, bad breath, etc.): independent (4), needs mild assistance/reminders (3), needs moderate assistance (2), does almost everything with assistance (1), full support (0). | |

| Social and emotional (SOC) | |

| Participation in activities: full (4), generally participates (3), sometimes participates (2), rarely participates (1), does not participate in any activity (0). | |

| Challenging behavior (shouts, spits, pinches, pushes, hits, undresses, insults): regular behavior (4) rarely (3), sometimes (2), most of the time (1), all the time (0). | |

| Total score for all clusters (GAC) | |

| Use of assistive devices | |

| Use of assistive device: wheelchair, walker, crutches, helmet, custom/medical shoes, support belt, braces, corset, communications device, glasses, hearing aid, false teeth, custom cutlery, other. | |

| Environmental changes | |

| Did any of the following occur recently: Change in staff, change in family, change in class/place of residence/isolation, change in schedule, change in medication. Other (specify): _____________. | |

References

- Mitic, M.; Aleksandrovic, M. Effects of Physical Exercise on Motor Skills and Body Composition of Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Detailed Review. J. Anthropol. Sport Phys. Educ. 2021, 5, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.; Scott, V. A model for fostering community capacity to support adults with intellectual disabilities who engage in challenging behavior: A scoping review. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 17446295221114619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben David, N.; Lotan, M.; Moran, D.S. How can Speech Therapists improve medical services of adults with intellectual and developmental disability (IDD)? Dash Bareshet 2022, 41, 56–67. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Welfare and Social Services. Rights of Individuals with Intellectual Disability and their Family. In Assessment of Intellectual Disabilities and Determination of Treatment; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services: Jerusalem, Israel, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/General/molsa-people-with-disabilities-people-with-developmental-intellectual-disabilities-about (accessed on 1 September 2020). (In Hebrew)

- Kadari, M.; Shiri, S. Literature Review on Diagnosis of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Definition, Diagnostic Procedures, and Psychological Assessment Tools, Procedures and Tools for Assessing Comorbidity. In Planning and Training; Division of Treatment of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services, Senior Division of Research: Jerusalem, Israel, 2015. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenkamp, T.I.; van der Schans, C.P.; van der Putten, A.A.; Waninge, A. Development of a Dutch Training/Education Program for a Healthy Lifestyle of People With Intellectual Disability. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 60, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, R.; Knapp, M.; Morrison, J.; Melville, C.; Allan, L.; Finlayson, J.; Cooper, S.A. Cost estimation of a health-check intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities in the UK. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Lee, C.E. Promoting Physical Activity Participation Among People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in South Korea. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Welfare and Social Services. Social Services Review Decade 2009–2018, chapter 6. In Of Individuals with Intellectual Disability; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services: Jerusalem, Israel, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/publications/reports/molsa-social-services-review-decade-2009-2018 (accessed on 1 August 2022). (In Hebrew)

- Ben David, N.; Lotan, M.; Moran, D.S. Development and validation of a functional screening tool for adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, C.L.; Walsh, D.; Fernandez, G.; Tournay, A.; Touchette, P.; Lott, I.T. Cognitive assessment using the Rapid Assessment for Developmental Disabilities, (RADD-2). J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, M.; Yalon-Chamovitz, S.; Weiss, P.L. Improving physical fitness of individuals with intellectual and developmental disability through a Virtual Reality Intervention Program. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle-Brown, J.; Beecham, J.; Leigh, J.; Whelton, R.; Richardson, L. Outcomes and costs of skilled support for people with severe or profound intellectual disability and complex needs. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 34, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, D.A.; Barbee, A.P. Prevalence of Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Direct Support Professionals in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Field. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 60, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desroches, M.L.; Fisher, K.; Ailey, S.; Stych, J.; McMillan, S.; Horan, P.; Marsden, D.; Trip, H.; Wilson, N. Supporting the needs of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic: An international, mixed methods study of nurses’ perspectives. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manduchi, B.; Fainman, G.M.; Walshe, M. Interventions for Feeding and Swallowing Disorders in Adults with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Dysphagia 2020, 35, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Balla, D.A.; Cicchetti, D.V. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Interview Edition, Survey Form; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bentur, N.; Epstein, S. SF-36: A measure for evaluating health-related Quality of Life. Gerontology 2001, 3/4, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Sardón, M.; Iglesias-de-Sena, H.; Fernández-Martín, L.C.; Mirón-Canelo, J.A. Do health and social support and personal autonomy have an influence on the health-related quality of life of individuals with intellectual disability? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garin, O.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Almansa, J.; Nieto, M.; Chatterji, S.; Vilagut, G.; Alonso, J.; Cieza, A.; Svetskova, O.; Burger, H.; et al. Validation of the “World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2” in patients with chronic diseases. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arvidsson, P.; Granlund, M.; Thyberg, M. How are the activity and participation aspects of the ICF used? Examples from studies of people with intellectual disability. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 36, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, K.-R.; Dyke, P.; Girdler, S.; Bourrke, J.; Leonard, H. Young adults with intellectual disability transitioning from school to post school: A literature review framed within the ICF. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1747–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonsson, R.J. ICF-CI: A Universal Tool for Documentation of Disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 6, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Paiva, A.F.; Nolan, A.; Thumser, C.; Santos, F.H. Screening of Cognitive Changes in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, F.; De Looff, P.; van Erp, S.; Nijman, H.; Didden, R. The adaptive ability performance test (ADAPT): A factor analytic study in clients with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13044 (accessed on 1 August 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakland, T.; Iliescu, D.; Chen, H.; Honglei, J. Cross-National Assessment of Adaptive Behavior Scale in Three Countries. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2013, 31, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhak, M. Chapter 6: Description of the Israeli Study. In ABAS II—An Instrument for Assessing Adaptive Behavior, Administration Manual, 2nd ed.; Ben Hamo, M., Translator; PsychTech WPS Publishing: Torrance, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 99–105. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, N. Work Outline in the Field of Individual Programs for Individuals with Disabilities. In Definition, Working Principles, and Modes of Execution; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services, Division of Disabilities for Assessment, Awareness, and Programs: Jerusalem, Israel, 2019. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Baksh, R.A.; Strydom, A.; Pape, S.E.; Chan, L.F.; Gulliford, M.C. Susceptibility to COVID-19 Diagnosis in People with Down Syndrome Compared to the General Population: Matched-Cohort Study Using Primary Care Electronic Records in the UK. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Pereira, C.; Hardy, J.; Bobbette, N.; Sockalingam, S.; Lunsky, Y. Virtual Education Program to Support Providers Caring for People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Rapid Development and Evaluation Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e28933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, D.; Esposito, G. Management and Support of Individuals with Developmental Disabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 125, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, S.L.; Fleming, V.; Piro-Gambetti, B.; Cohen, A.; Ances, B.M.; Yassa, M.A.; Schupf, N. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Daily Life, Mood, and Behavior of Adults with Down Syndrome. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, K.; Perera, B. COVID-19 and People with Intellectual Disability: Impacts of a Pandemic. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M. Care and Rehabilitation Institutions for People with Intellectual Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Polish Experiences. Int. Soc. Work. 2021, 00208728211060471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Welfare and Social Services. An Official Response to a Request Regarding Budgetary Expenses by the MWSS; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services: Jerusalem, Israel, 2021. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Stavropoulos, K.K.M.; Bolourian, Y.; Blacher, J. A Scoping Review of Telehealth Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben David, N.; Lotan, M.; Moran, D.S. The impact of COVID-19-related restrictions on functional skills among adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2022. under second review. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.; Hudson, E.; Morrissey, S.; Sharma, D.; Kelly, D.; Doody, O. Management of psychotropic medications in adults with intellectual disability: A scoping review. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 2486–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. ICF Beginner’s Guide: Toward a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health. In ICF—The International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/icf-beginner-s-guide-toward-a-common-language-for-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Lotan, M.; Ippolito, E.; Favetta, M.; Romano, A. Skype Supervised, Individualized, Home-Based Rehabilitation Programs for Individuals with Rett Syndrome and their Families–Parental Satisfaction and Point of View. Front. Psychol. 2021, 3995, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Dor, N.; Cohen, N.; Shemesh, A. Collection of Services and Treatment Plans for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities; Ministry of Welfare and Social Services, Division of Treatment of Individuals with Intellectual disabilities: Jerusalem, Israel, 2016. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Oudshoorn, C.E.; Frielink, N.; Nijs, S.L.; Embregts, P.J. Psychological eHealth interventions for people with intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 950–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, G.H.; Beail, N. Long-COVID in people with intellectual disabilities: A call for research of a neglected area. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysta, K.; Romańczyk, M.; Diefenbacher, A.; Krzystanek, M. Telemedicine treatment and care for patients with intellectual disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, M.; Downs, J.; Elefant, C. A pilot study delivering physiotherapy support for Rett syndrome using a telehealth framework suitable for COVID-19 lockdown. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2021, 24, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlot, L.R.; Hodge, S.M.; Holland, A.L.; Frazier, J.A. Psychiatric diagnostic dilemmas among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2022, 66, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R.; Perera, B.; Roy, A.; Courtenay, K.; Laugharne, R.; Sivan, M. Post-COVID syndrome and adults with intellectual disability: Another vulnerable population forgotten? Br. J. Psychiatry 2022, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howkins, J.; Hassiotis, A.; Bradley, E.; Levitas, A.; Sappok, T.; Sinai, A.; Shankar, R. International Clinician Perspectives on Pandemic-associated Stress in Supporting People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, L.; Ward, M.; DiCosimo, A.; Baunta, S.; Cunningham, C.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Briggs, R. Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM Int. J. Med. 2021, 114, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalmstra, T.A.; Elema, A.; van Gils, W.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; van der Sluis, C.K.; van der Putten, A.A. Development and sensibility assessment of a health-related quality of life instrument for adults with severe disabilities who are non-ambulatory. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, A.; Cavkaytar, A. Development of A Daily Living Education Program for Individuals With Intellectual Disabilities Under Protective Care. Rehabil. Res. Policy Educ. 2022, 35, 280–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Allen, A.P.; Fallon, M.; Mulryan, N.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M.; Sheerin, F. The challenges of mental health of staff working with people with intellectual disabilities during COVID-19––A systematic review. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 17446295221136231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, A.; Ippolito, E.; Risoli, C.; Malerba, E.; Favetta, M.; Sancesario, A.; Moran, D.S. Intensive Postural and Motor Activity Program Reduces Scoliosis Progression in People with Rett Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Sk Abd Razak, R.; Suddin, L.S.; Mahmud, A.; Kamaralzaman, S.; Yusri, G. The Economic Burden and Determinant Factors of Parents/Caregivers of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Malaysia: A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben David, N.; Lotan, M.; Moran, D.S. A New Screening Tool for Rapid Diagnosis of Functional and Environmental Factors Influencing Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2991. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12122991

Ben David N, Lotan M, Moran DS. A New Screening Tool for Rapid Diagnosis of Functional and Environmental Factors Influencing Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(12):2991. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12122991

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen David, Nophar, Meir Lotan, and Daniel Sender Moran. 2022. "A New Screening Tool for Rapid Diagnosis of Functional and Environmental Factors Influencing Adults with Intellectual Disabilities" Diagnostics 12, no. 12: 2991. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12122991

APA StyleBen David, N., Lotan, M., & Moran, D. S. (2022). A New Screening Tool for Rapid Diagnosis of Functional and Environmental Factors Influencing Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Diagnostics, 12(12), 2991. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12122991