Evaluation of Nine Commercial Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Human Hepatic Cyst Echinococcosis and the Differential Diagnosis with Other Focal Liver Lesions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

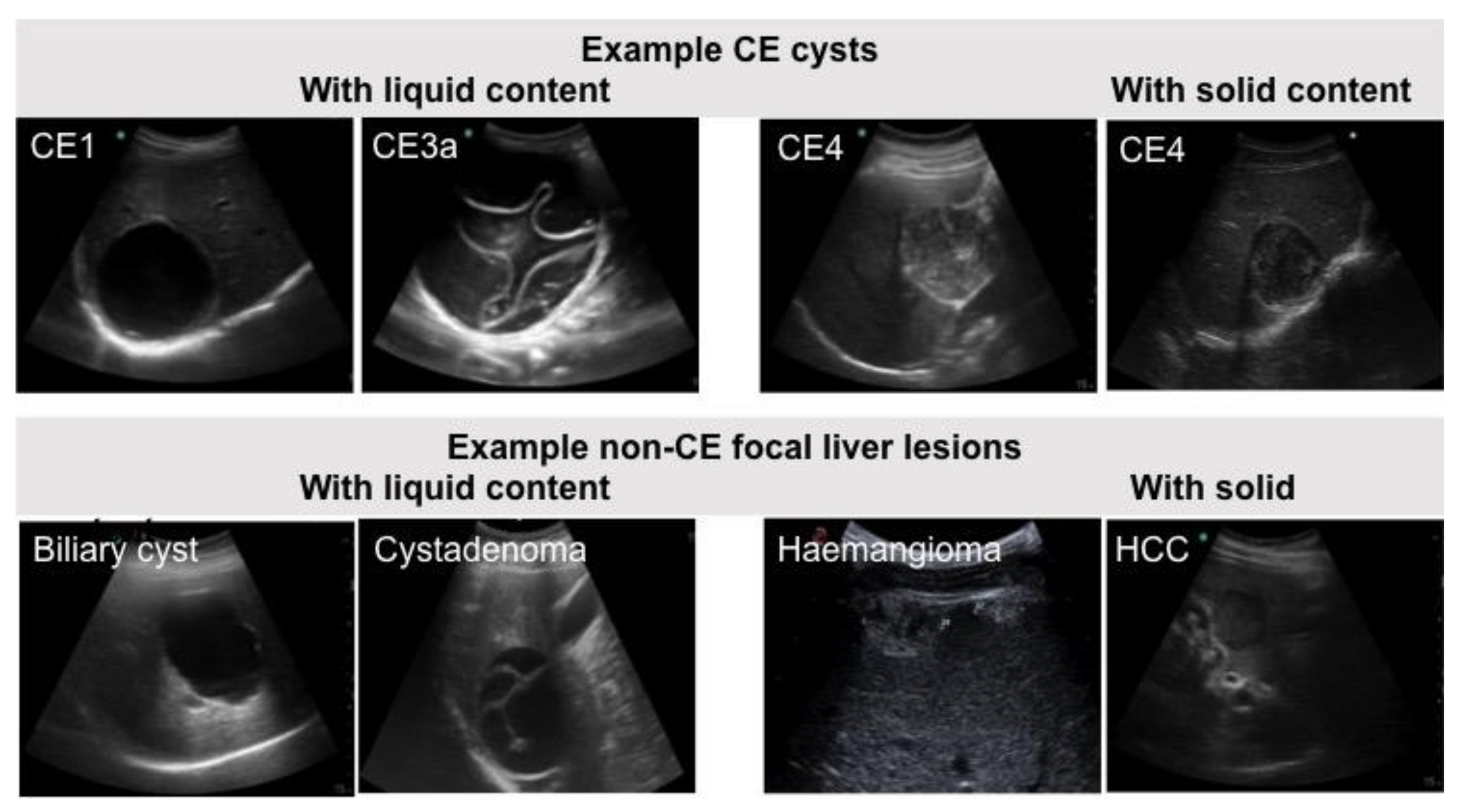

2.2. Samples Panel and Classification

2.3. Diagnostic Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Serum Samples Cohort

4. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Accuracy of Assays

4.1. Single Tests

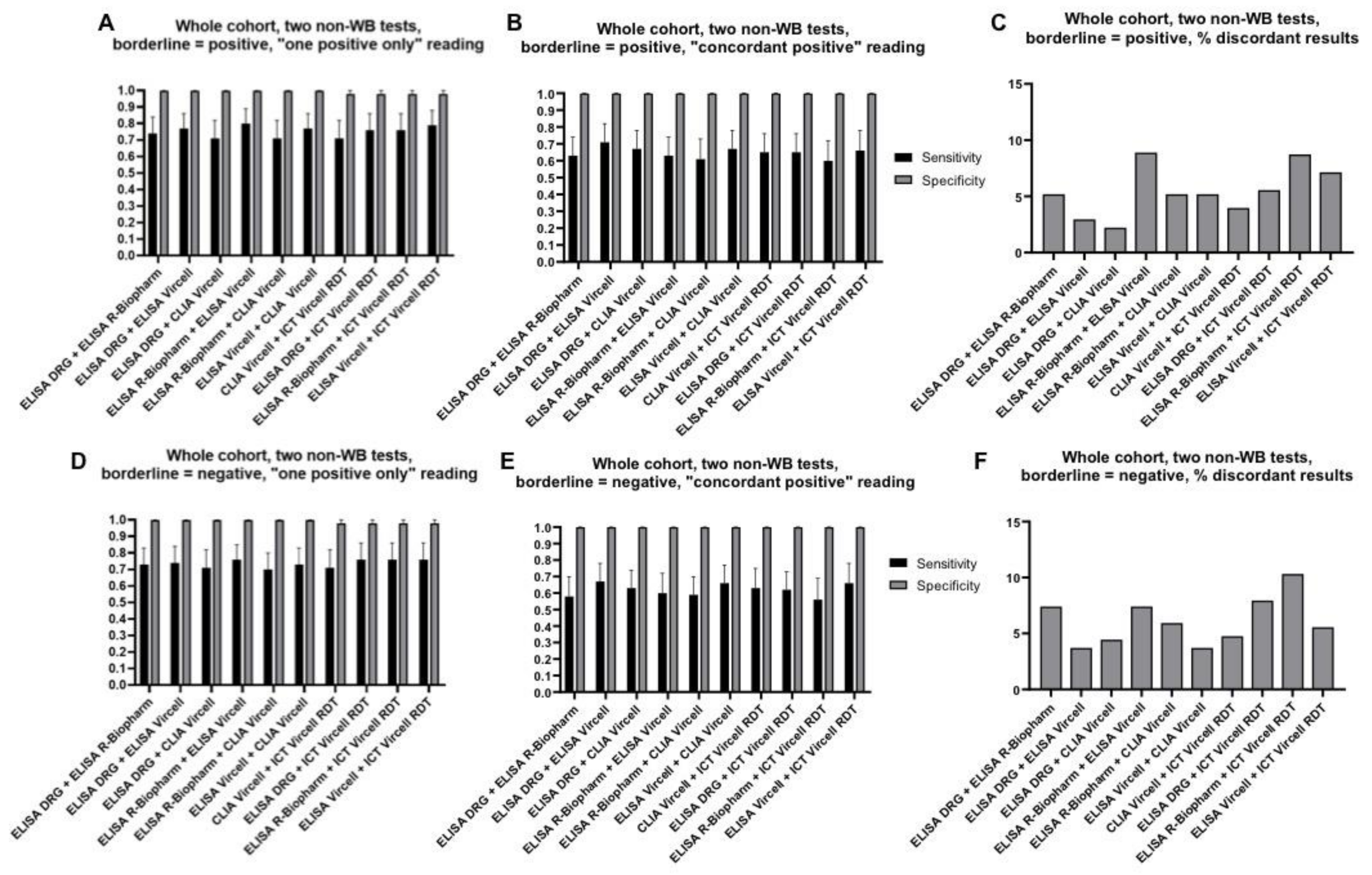

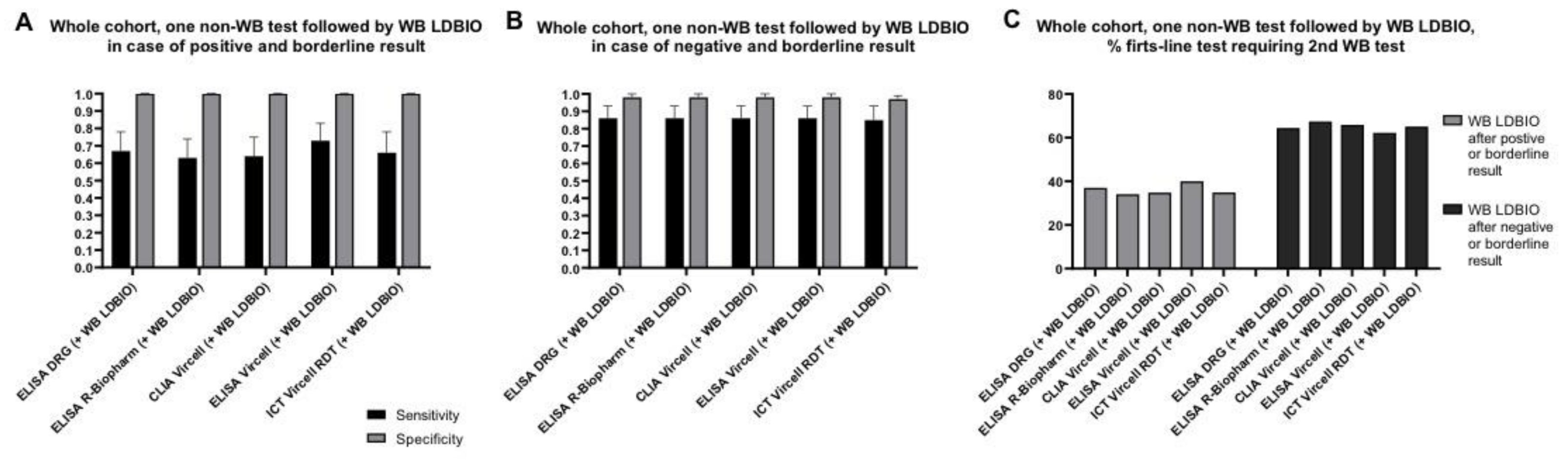

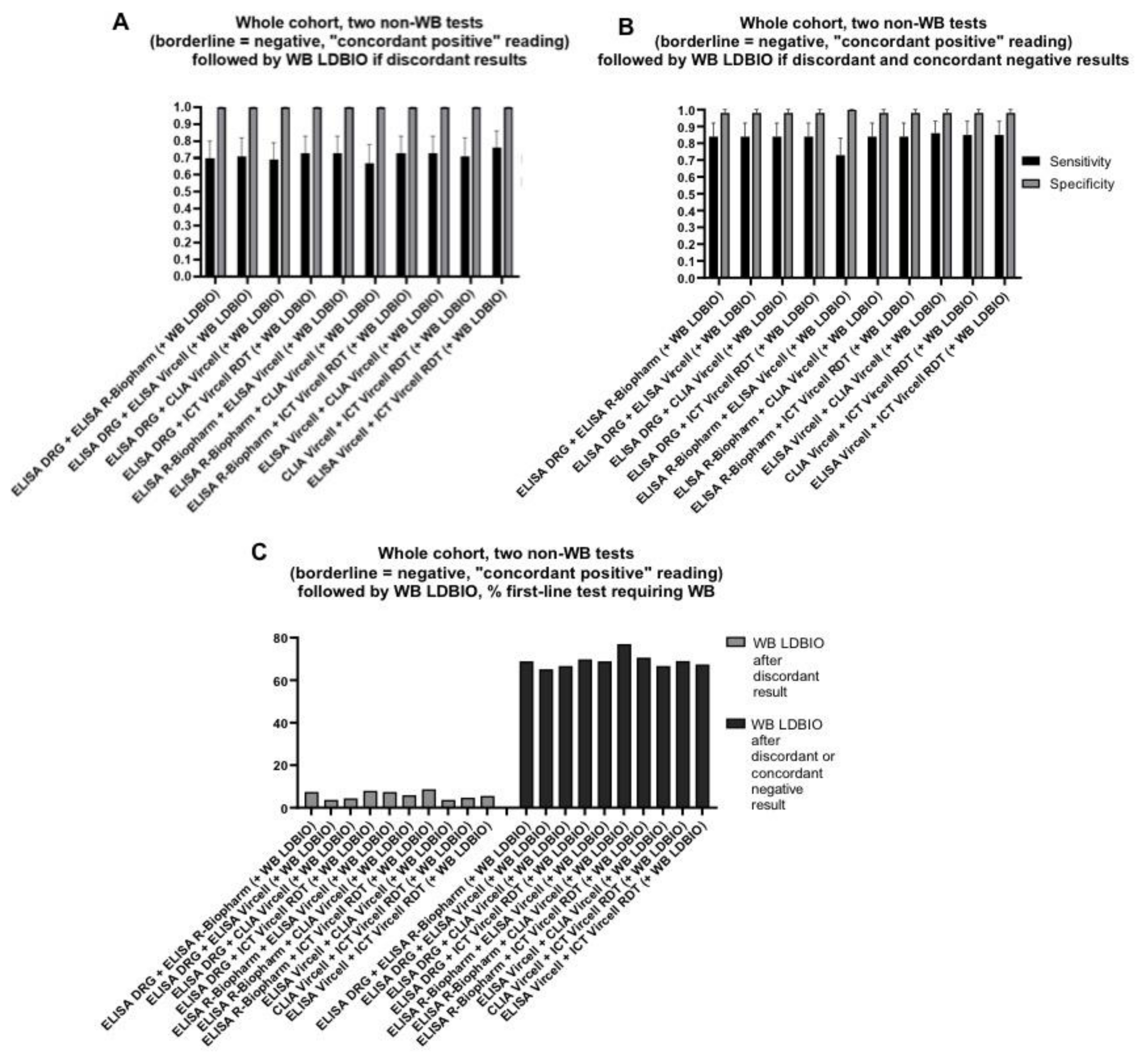

4.2. Combination of Two Tests

4.3. Combination of Three Tests

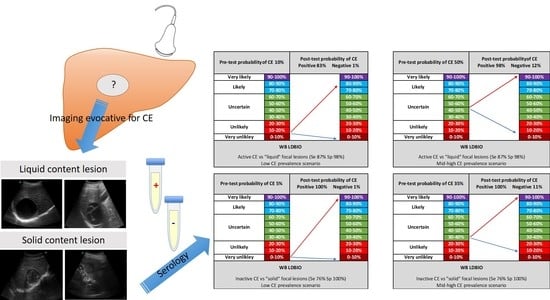

5. Simulation of Post-Test Probabilities

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casulli, A.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Tamarozzi, F. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deplazes, P.; Rinaldi, L.; Alvarez Rojas, C.A.; Torgerson, P.R.; Harandi, M.F.; Romig, T.; Antolova, D.; Schurer, J.M.; Lahman, S.; Cringoli, G.; et al. Global distribution of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Adv. Parasitol. 2017, 95, 315–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.S.; Hegglin, D.; Lightowlers, M.W.; Torgerson, P.R.; Wang, Q. Echinococcosis: Control and prevention. Adv. Parasitol. 2017, 96, 55–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kern, P.; Menezes da Silva, A.; Akhan, O.; Mullhaupt, B.; Vizcaychipi, K.A.; Budke, C.; Vuitton, D.A. The echinococcoses: Diagnosis, clinical management and burden of disease. Adv. Parasitol. 2017, 96, 259–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, E.; Kern, P.; Vuitton, D.A.; Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, M.; Weber, T.F.; Junghanss, T. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: State of the art and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles-Lucas, M.; Casulli, A.; Conraths, F.J.; Muller, N. Laboratory diagnosis of Echinococcus spp. in human patients and infected animals. Adv. Parasitol. 2017, 96, 159–257. [Google Scholar]

- Tamarozzi, F.; Mariconti, M.; Covini, I.; Brunetti, E. Rapid diagnostic tests for the serodiagnosis of human cystic echinococcosis. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2017, 110, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rue, M.L.; Yamano, K.; Almeida, C.E.; Iesbich, M.P.; Fernandes, C.D.; Goto, A.; Kouguchi, H.; Takahashi, K. Serological reactivity of patients with Echinococcus infections (E. granulosus, E. vogeli, and E. multilocularis) against three antigen B subunits. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liance, M.; Janin, V.; Bresson-Hadni, S.; Vuitton, D.A.; Houin, R.; Piarroux, R. Immunodiagnosis of Echinococcus infections: Confirmatory testing and species differentiation by a new commercial Western Blot. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 3718–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, M.; Mickan, C.; Weber, T.F.; Junghanss, T. Pitfalls in diagnosis and treatment of alveolar echinococcosis: A sentinel case series. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015, 2, e000036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez, A.; Muro, A.; Barrera, I.; Ramos, G.; Orduna, A.; Siles-Lucas, M. Usefulness of four different Echinococcus granulosus recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of unilocular hydatid disease (UHD) and postsurgical follow-up of patients treated for UHD. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissandrin, R.; Tamarozzi, F.; Piccoli, L.; Tinelli, C.; De Silvestri, A.; Mariconti, M.; Meroni, V.; Genco, F.; Brunetti, E. Factors influencing the serological response in hepatic Echinococcus granulosus infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vola, A.; Manciulli, T.; De Silvestri, A.; Lissandrin, R.; Mariconti, M.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Brunetti, E.; Tamarozzi, F. Diagnostic performances of commercial ELISA, Indirect Hemagglutination, and Western Blot in differentiation of hepatic echinococcal and non-echinococcal lesions: A retrospective analysis of data from a single referral centre. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 1345–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Equator Network. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/stard/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Chebli, H.; El Laamrani Idrissi, A.; Benazzouz, M.; Lmimouni, B.E.; Nhammi, H.; Elabandouni, M.; Youbi, M.; Afifi, R.; Tahiri, S.; El Feydi, A.E.; et al. Human cystic echinococcosis in Morocco: Ultrasound screening in the Mid Atlas through an Italian-Moroccan partnership. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajenaru, N.; Balaban, V.; Savulescu, F.; Campeanu, I.; Patrascu, T. Hepatic hemangioma-review. J. Med. Life 2015, 8, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach, T.E.; Engler, P.; Kratzer, W.; Oeztuerk, S.; Seufferlein, T.; Haenle, M.M.; Graeter, T. Prevalence of benign focal liver lesions: Ultrasound investigation of 45,319 hospital patients. Abdom. Radiol. 2016, 41, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantinga, M.A.; Gevers, T.J.; Drenth, J.P. Evaluation of hepatic cystic lesions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3543–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.; Chavez, L.; Surani, S. Hepatic hemangioma: What internists need to know. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocchegiani, F.; Vincenzi, P.; Coletta, M.; Agostini, A.; Marzioni, M.; Baroni, G.S.; Giovagnoli, A.; Guerrieri, M.; Marmorale, C.; Risaliti, A.; et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hepatic haemangioma with specific reference to the risk of rupture: A large retrospective cross-sectional study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Muralidharan, P.; Raj, J.P. An updated review of cystic hepatic lesions. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2019, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, P.L.; Bonifacio, N.; Gilman, R.H.; Lopera, L.; Silva, B.; Takumoto, R.; Verastegui, M.; Cabrera, L. Field diagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus infection among intermediate and definitive hosts in an endemic focus of human cystic echinococcosis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999, 93, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambesh, M.A.; Craig, P.S.; Macpherson, C.N.; Rogan, M.T.; Gusbi, A.M.; Echtuish, E.F. An extensive ultrasound and serologic study to investigate the prevalence of human cystic echinococcosis in northern Libya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999, 60, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldin, C.; Raffetin, A.; Bouiller, K.; Hansmann, Y.; Roblot, F.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med. Mal. Infect. 2019, 49, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapa, J.S.; Saraiva, R.M.; Hasslocher-Moreno, A.M.; Georg, I.; Souza, A.S.; Xavier, S.S.; do Brasil, P.E.A.A. Dealing with initial inconclusive serological results for chronic Chagas disease in clinical practice. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraquin, A.; Zait, H.; Grenouillet, F.E.; Moreau, E.; Hamrioui, B.; Grenouillet, F. Large-scale evaluation of a rapid diagnostic test for human cystic echinococcosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 89, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, E.; Bandehpour, M.; Pazoki, R.; Taghipoor-Lailabadi, N.; Khazan, H.; Mosaffa, N.; Nazaripouya, M.R.; Kazemi, B. Application of recombinant Echinococcus granulosus antigen B to ELISA kits for diagnosing hydatidosis. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Thapar, S.; Khillan, V.; Gupta, P.; Rastogi, A.; Gupta, E. Comparative evaluation of Echinococcus serology with cytology for the diagnosis of hepatic hydatid disease. J. Lab. Physicians 2020, 12, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tamer, G.S.; Dündar, D.; Uzuner, H.; Baydemir, C. Evaluation of immunochromatographic test for the detection of antibodies against Echinococcosis granulosus. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 2, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Gavidia, C.M.; Gonzalez, A.E.; Zhang, W.; McManus, D.P.; Lopera, L.; Ninaquispe, B.; Garcia, H.H.; Rodríguez, S.; Verastegui, M.; Calderon, C.; et al. Diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis, central Peruvian Highlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tamarozzi, F.; Longoni, S.S.; Vola, A.; Degani, M.; Tais, S.; Rizzi, E.; Prato, M.; Scarso, S.; Silva, R.; Brunetti, E.; et al. Evaluation of Nine Commercial Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Human Hepatic Cyst Echinococcosis and the Differential Diagnosis with Other Focal Liver Lesions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11020167

Tamarozzi F, Longoni SS, Vola A, Degani M, Tais S, Rizzi E, Prato M, Scarso S, Silva R, Brunetti E, et al. Evaluation of Nine Commercial Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Human Hepatic Cyst Echinococcosis and the Differential Diagnosis with Other Focal Liver Lesions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(2):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11020167

Chicago/Turabian StyleTamarozzi, Francesca, Silvia Stefania Longoni, Ambra Vola, Monica Degani, Stefano Tais, Eleonora Rizzi, Marco Prato, Salvatore Scarso, Ronaldo Silva, Enrico Brunetti, and et al. 2021. "Evaluation of Nine Commercial Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Human Hepatic Cyst Echinococcosis and the Differential Diagnosis with Other Focal Liver Lesions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study" Diagnostics 11, no. 2: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11020167

APA StyleTamarozzi, F., Longoni, S. S., Vola, A., Degani, M., Tais, S., Rizzi, E., Prato, M., Scarso, S., Silva, R., Brunetti, E., Bisoffi, Z., & Perandin, F. (2021). Evaluation of Nine Commercial Serological Tests for the Diagnosis of Human Hepatic Cyst Echinococcosis and the Differential Diagnosis with Other Focal Liver Lesions: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Diagnostics, 11(2), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11020167