Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Collection

- Nuck[All Fields] AND (“endometriosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “endometriosis”[All Fields])

- Nuck[All Fields] AND (“cysts”[MeSH Terms] OR “cysts”[All Fields] OR “cyst”[All Fields]) AND (“endometriosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “endometriosis”[All Fields]).

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

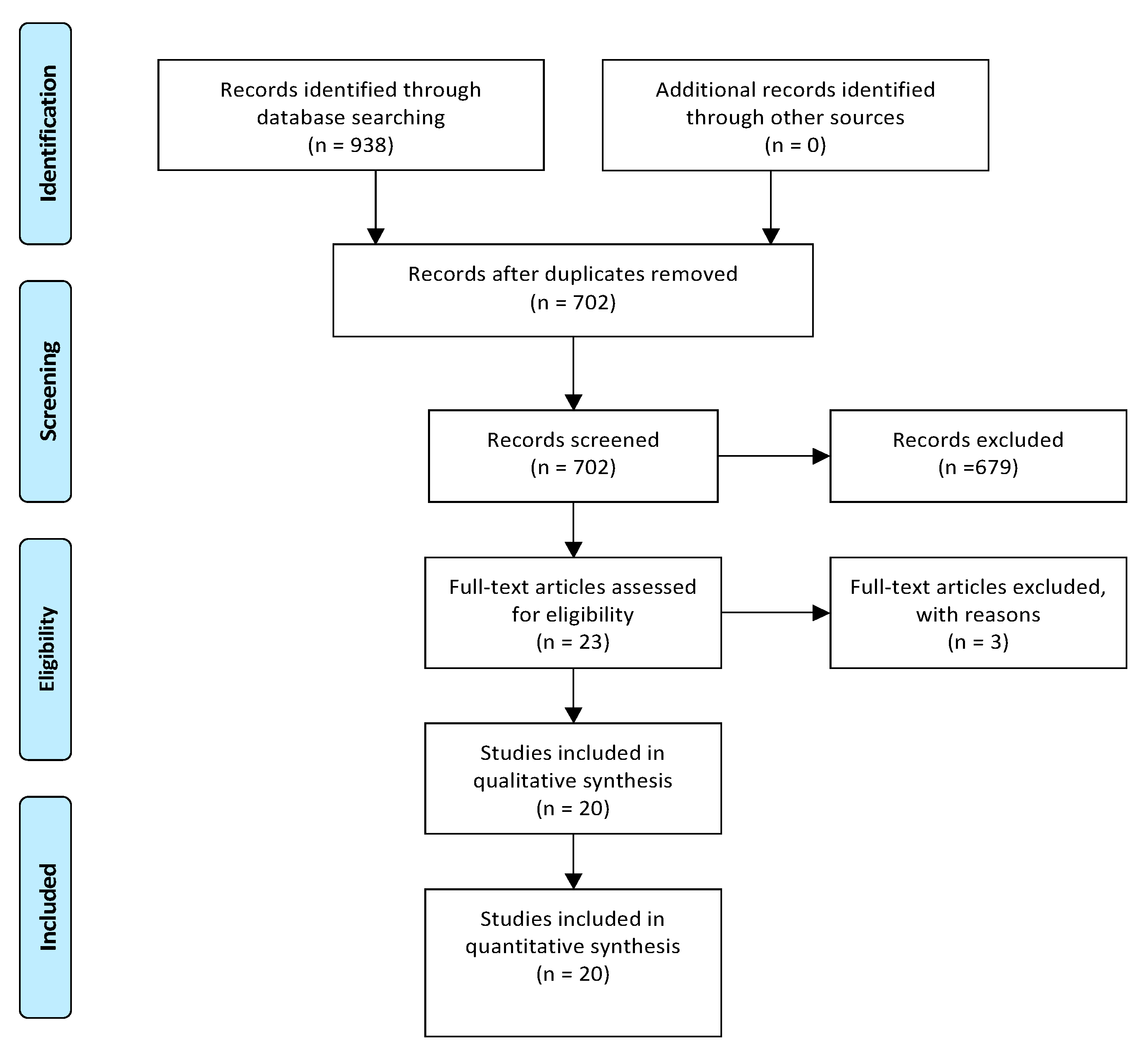

3.1. Included and Excluded Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Main Characteristics of Included Studies and Disease-Related Characteristics

3.4. Perioperative Outcomes

3.5. Endometriosis-Related Malignancy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shafrir, A.L.; Farland, L.V.; Shah, D.K.; Harris, H.R.; Kvaskoff, M.; Zondervan, K.; Missmer, S.A. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, M.; Ballard, K.; Farquhar, C. Endometriosis. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2014, 348, g1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitawaki, J.; Kado, N.; Ishihara, H.; Koshiba, H.; Kitaoka, Y.; Honjo, H. Endometriosis: The pathophysiology as an estrogen-dependent disease. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 83, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, M.; Virgilio, B.A.; Laganà, A.S.; Bernardini, T.; Fattizzi, N.; Neri, M.; Guerriero, S. Differential Diagnosis of Endometriosis by Ultrasound: A Rising Challenge. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcoverde, F.V.L.; Andres, M.P.; Borrelli, G.M.; Barbosa, P.A.; Abrão, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Surgery for Endometriosis Improves Major Domains of Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlyle, D.; Khader, T.; Lam, D.; Vadivelu, N.; Shiwlochan, D.; Yonghee, C. Endometriosis Pain Management: A Review. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2020, 24, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondi-Pafiti, A.; Spanidou-Carvouni, H.; Papadias, K.; Hatzistamou-Kiari, I.; Kontogianni, K.; Liapis, A.; Smyrniotis, V. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis: Clinicopathological study of 14 cases. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 31, 302–304. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, K.; Kotani, Y.; Nakai, H.; Matsumura, N. Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer: The Origin and Targeted Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsich, F.; Causa Andrieu, P.I.; Wernicke, A.; Patrono, M.G.; Napoli, M.N.; Chacon, C.R.B.; Nicola, R. Extra-uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma arising from deep infiltrating endometriosis. Clin. Imaging 2020, 67, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audebert, A.; Petousis, S.; Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Ravanos, K.; Prapas, N.; Prapas, Y. Anatomic distribution of endometriosis: A reappraisal based on series of 1101 patients. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 230, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.R., 2nd; Keeler, E.R.; Euscher, E.D.; McCutcheon, I.E. Cyclic sciatica from extrapelvic endometriosis affecting the sciatic nerve. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2011, 14, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodromidou, A.; Machairas, N.; Paspala, A.; Hasemaki, N.; Sotiropoulos, G.C. Diagnosis, surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes of hepatic endometriosis: A systematic review. Ann. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, H.; King, M.; Rosenberg, H.K.; Rosen, A.; Wilck, E.; Simpson, W.L. Anatomy and pathology of the canal of Nuck. Clin. Imaging 2018, 51, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acién, P.; Sánchez del Campo, F.; Mayol, M.J.; Acién, M. The female gubernaculum: Role in the embryology and development of the genital tract and in the possible genesis of malformations. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 159, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, R.S.; Loukas, M.; Shoja, M.M.; Salter, E.G.; Oakes, W.J. Indirect inguinal hernia of the urinary bladder through a persistent canal of Nuck: Case report. Hernia J. Hernias Abdom. Wall Surg. 2007, 11, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, M.A.; Squires, J.E.; Tadros, S.; Squires, J.H. Canal of Nuck hernia: A multimodality imaging review. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Sultan, S.; Haffar, S.; Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.B.; Te Linde, R.W. External Endometriosis—The Scourage of the Private Patient. Ann. Surg. 1950, 131, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.; Miles, R.M. Inguinal endometriosis. Ann. Surg. 1960, 151, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, C.; Gammeri, E.; Foti, A.; Rossitto, M.; Cucinotta, E. Vulvar endometriosis and Nuck canal. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2014, 85, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.C.J.; Toker, C.; Masi, J.D.; George Elias, E. Primary low grade adenocarcinoma occurring in the inguinal region. Cancer 1979, 44, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesko, J.D.; Gates, H.; McDonald, T.W.; Youmans, R.; Lewis, J. Clear cell (“mesonephroid”) adenocarcinoma of the vulva arising in endometriosis: A case report. Gynecol. Oncol. 1988, 29, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, W.; Pelkey, T.; Rice, L.; Andersen, W. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the vulva arising in extraovarian endometriosis: A case report and literature review. Gynecol. Oncol. 1998, 71, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervini, P.; Wu, L.; Shenker, R.; O’blenes, C.; Mahoney, J. Endometriosis in the canal of Nuck: Atypical manifestations in an unusual location. Can. J. Plast. Surg. 2004, 12, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, A.; Reed, C.M.; Bui-Mansfield, L.T.; Russell, M.J.; Whitford, W. Radiologic-pathologic conference of Brooke Army Medical Center: Endometriosis of the canal of Nuck. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 186, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; Chao, A.-S.; Wang, T.-H.; Wu, C.-T.; Chao, A.; Lai, C.-H. Challenge in the management of endometriosis in the canal of Nuck. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 936.e9–936.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Tsuchiya, J.; Tachibana, S. A case of primary endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from the hydrocele of the canal of Nuck. J. Jpn. Surg 2010, 71, 2145–2149. [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta, M.; Minutoli, F.; Mileto, A.; Racchiusa, S.; Donato, R.; Bottari, A.; Blandino, A. Nuck canal endometriosis: MR imaging findings and clinical features. Abdom. Imaging 2010, 35, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albal, M.; Zaki, B.M.; Ansari, I. Endometriosis in Cyst of Nuck’s canal: A Rare Presentation. J. Case Rep. 2014, 4, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagul, A.; Jones, S.; Dundas, S.; Aly, E.H. Endometriosis in the canal of Nuck hydrocele: An unusual presentation. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2011, 2, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, J.S.; Barbero, P.; Tejerizo, A.; Guillén, C.; Strate, C. A laparoscopic approach to Nuck’s duct endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, e103–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendon, C.L.; Goodacre, T.E.; Kennedy, S.H. Left-sided Canal of Nuck Endometriosis: A Case Report. J. Endometr. 2011, 3, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, D.; Matsumoto, N.; Kamata, S.; Kaneko, K. Ectopic pregnancy developing in a cyst of the canal of Nuck. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, Y.; Nakajima, S.; Yano, F.; Eto, K.; Omura, N.; Yanaga, K. Mesothelial cyst with endometriosis mimicking a Nuck cyst. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 2014, rju067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoshi, K.; Mizumoto, M.; Kinoshita, K. Endometriosis-associated hydrocele of the canal of Nuck with immunohistochemical confirmation: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motooka, Y.; Motohara, T.; Honda, R.; Tashiro, H.; Mikami, Y.; Katabuchi, H. Radical resection of an endometrioid carcinoma arising from endometriosis in the round ligament within the right canal of Nuck: A case report and literature review. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, H.; Tsumura, H.; Kanehiro, T.; Yamaoka, H.; Taogoshi, H.; Murao, N. Clinical Characteristics and Surgical Treatment for Inguinal Endometriosis in Young Women of Reproductive Age. Dig. Surg. 2019, 36, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviraj, S.; Priatharshan, M. A rare case of endometriosis in the canal of Nuck. J. Postgrad. Inst. Med. 2019, 6, E95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Kuruvilla, R.; Ramakrishnan, K. Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck—An Unusual Case of Inguinal Swelling. Indian J. Surg. 2019, 82, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, S.; Ogura, K.; Ashizawa, K.; Sakaguchi, A.; Wada, R.; Matsumoto, T. Hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck with Endometriosis: Right-Side Dominance Confirmed by Literature Review and Statistical Analysis. Case Rep. Pathol. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, H.; Uehara, Y. Inguinal Endometriosis: An Unusual Cause of Groin Pain. Balk. Med. J. 2020, 37, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak, G.; Ergul, E.; Sarıkaya, S.; Yazgan, A. Endometriosis of the groin hernia sac: Report of a case and review of the literature. Hernia J. Hernias Abdom. Wall Surg. 2010, 14, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihni, I.; Karakose, O.; Ozcelik, K.C.; Pulat, H.; Eroglu, H.E.; Bozkurt, K.K. Endometriosis within the inguinal hernia sac. Turk. J. Surg. 2020, 36, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, M.P.; Arcoverde, F.V.L.; Souza, C.C.C.; Fernandes, L.F.C.; Abrão, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Extrapelvic Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfhagen, N.; Simons, N.E.; de Jong, K.H.; van Kesteren, P.J.M.; Simons, M.P. Inguinal endometriosis, a rare entity of which surgeons should be aware: Clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of nine cases. Hernia J. Hernias Abdom. Wall Surg. 2018, 22, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromidou, A.; Paspala, A.; Schizas, D.; Spartalis, E.; Nastos, C.; Machairas, N. Cyst of the Canal of Nuck in adult females: A case report and systematic review. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 12, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.J.; Fakhreldin, M.; Maclean, A.; Dobson, L.; Nancarrow, L.; Bradfield, A.; Choi, F.; Daley, D.; Tempest, N.; Hapangama, D.K. Endometriosis and the fallopian tubes: Theories of origin and clinical implications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, L.; Dietze, R.; Kudipudi, P.K.; Horné, F.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I. Endometriosis in MRKH cases as a proof for the coelomic metaplasia hypothesis? Reproduction 2019, 158, R41–R47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S.; Conway, F.; Pascual, M.A.; Graupera, B.; Ajossa, S.; Neri, M.; Musa, E.; Pedrassani, M.; Alcazar, J.L. Ultrasonography and Atypical Sites of Endometriosis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.; Marques, J.P.; Falcao, F. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck presenting as a sausage-shaped mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakhari, A.; Delpero, E.; McKeown, S.; Tomlinson, G.; Bougie, O.; Murji, A. Endometriosis recurrence following post-operative hormonal suppression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author; Year | QAS | Parity | Surgery for EM, Previous Surgery | Primary Symptom/Association with Menstruation | Type of Surgical Repair | Pathology-IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun; 1979 [22] | 5/5 | NA | No | Painless swelling (7 year) became painful (4 year)/no | Hernia repair with mass excision and sac repair | Low grade papillary adenocarcinoma |

| Mesko; 1988 [23] | 4/5 | 2 | R inguinal herniorrhaphy, TAH-BSO | Gradually enlarging inguinal mass/no | Two inguinal cystic masses removal and exploratory laparotomy with RSO | Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from NC- EM |

| Irvin; 1998 [24] | 5/5 | 4 | TAH-BSO (no EM-related) | Enlarging mass/no | Radical L hemivulvectomy with clitorectomy | Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the vulva, arising from the extrapelvic portion of the round ligament, within NC |

| Cervini; 2004 [25] | 2/5 | 1 | No | Gradually enlarging pubic mass/yes | Excisional biopsy | EM |

| Kirkpatrick; 2006 [26] | 2/5 | NA | NA | Painless mass-incidental finding in adrenal adenoma investigation/no | Biopsy (US guided) | EM |

| Wang; 2009 [27] | 4/5 | 0 | NA | Painful mass/yes | Laparoscopy for pelvic EM and excision of inguinal subcutaneous bulging mass | EM |

| Ito; 2010 [28] | 3/5 | NA | TAH-BSO (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma-stage Ia-14 years) | Mass/no | Tumor resection, mesh-plug repair | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma |

| Gaeta; 2010 [29] | 3/5 | NA | NA | 4 inguinal painless masses; 2 inguinal discomfort; 2 cyclic pain | NA | NA |

| Albal; 2011 [30] | 3/5 | NA | No | Inguinal swelling/no | En block lump excision | Loculated cyst of NC with deposition of endometrial tissue |

| Bagul; 2011 [31] | 3/5 | NA | No | Painful mass/no | Aspiration of hydrocele fluid and sac transfixed and en bloc excised | Multiple foci of EM, hemosiderin deposition, inflammation and fibrosis |

| Jimnez; 2011 [32] | 3/5 | 1 | R nephrectomy | Painful mass/yes | Exploratory laparoscopy, cyst removal, and inguinal ring defect repair with mesh | NA |

| Bendon; 2011 [33] | 4/5 | 0 | IUD (prior 9 months), R inguinal hernia repair | Painful groin mass/yes | NC dissection and lesion within the sac excision | Fibroadipose tissue with evidence of EM |

| Noguchi; 2014 [34] | 3/5 | 4 | NA | Groin swelling; irregular genital bleeding; urine pregnancy test positive (hCG = 3090) | Exploratory laparotomy, extraction of right inguinal mass, closure of deep inguinal ring | Ectopic pregnancy and Nuck EM |

| Uno; 2014 [35] | 4/5 | 0 | NA | Painful groin mass/no | Inguinal approach, dissection, and cyst excision | Mesothelial cells lined the wall of the cyst with degeneration, inflammation, hemorrhage, formation of hyperplastic collagen fiber and hemosiderosis, IC: CD10(+), ER(+), PgR(+) |

| Okoshi; 2017 [36] | 4/5 | 1 | Laparoscopy for intrapelvic EM (10 years ago) | Pubic painful mass/no | Anterior open cyst excision and internal inguinal; ring repair with mesh | Cyst lined with mesothelial-like cells and accompanied by partial subcapsular hemorrhage, endometrium-like cystic wall IC: podoplanin & ER receptors |

| Motooka; 2018 [37] | 5/5 | 2 | No | Pubic painful and bleeding mass/no | Inguinal tumor resection, partial radical vulvectomy, clitoridectomy, R pectineal muscles, rectus abdominis muscles, oblique abdominal muscles, inguinal ligament and round ligament resection, bilateral inguinal LND-reconstruction with flaps | Endometrioid carcinoma associated with EM on the round ligament in R NC |

| Niitsu; 2019 [38] a | 5/5 | NA | No | Inguinal mass /no (n = 1) | Open no hernia repair (n = 1) | EM |

| Inguinal mass /no (n = 3) | Open, inguinal hernia repair (Marcy’s) (n = 3) | |||||

| Inguinal mass/yes (n = 1) | Open, inguinal hernia repair (Marcy’s)-NC wall thickening (n = 3) | |||||

| Inguinal mass/no (n = 2) | ||||||

| Inguinal mass/yes (n = 1) | Open, no inguinal hernia repair-NC wall thickening (n = 1) | |||||

| Inguinal mass/no (n = 1) | Open no inguinal repair-NC wall thickening (n = 1) | |||||

| Inguinal mass/no (n = 1) | Open hernia repair (mesh)-NC wall thickening (n = 1) | |||||

| 2019; Raviraz [39] | 3/5 | 0 | No | Gradually enlarging, cyclically painful groin swelling, subfertility/yes | Open (patent processus vaginalis) | EM |

| Thomas; 2019 [40] | 2/5 | NA | No | Gradually enlarging cyclical painful groin swelling (1 year)/yes | Open excisional biopsy | Clusters of endometrial glands and stroma embedded in the fibrous tissue |

| Nagase; 2020 [41] | 5/5 | NA | No | Painful mass | Mass excision | Cyst lined by single-layered flat mesothelial cells- (hydrocele) with few glands of columnar cells accompanied by endometrial cells, hemorrhage and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, IC: single-layered flat cells calretinin +, podoplanin +, and WT-1 +, Columnar cells ER +, PR +, Round monotonous cells ER +, PR +, CD10 +, and WT-1 + |

| Author; Year | Type of Surgery (after Diagnosis of Malignancy) | Histological Type | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motooka; 2018 [37] | Partial radical vulvectomy, clitoridectomy, & resection of the R pectineal muscles, rectus abdominis muscles, oblique abdominal muscles, inguinal ligament, and round ligament. Bilateral inguinal LND en bloc & EL | Well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma, endometriosis- associated on the round ligament in the R NC Metastatic tumor was in inguinal and left external iliac lymph nodes | 12 months after the 1st surgery endometrial cancer stage IA, Grade I and 5 months after 2nd endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the right ovary IA Grade I |

| Ito; 2010 [28] | Open resection of the tumor with mesh repair | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the NC | No |

| Irvin; 1998 [24] | Left radical hemivulvectomy and clitorectomy | Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) of the vulva, arising from the extrapelvic portion of the round ligament, within the NC Tumor arose from EM | Lung metastasis 21 months after the 1st surgery (wedge resection of the metastatic pulmonary nodule) and 9 months later lung metastasis (right upper lobectomy) |

| Mesko; 1988 [23] | Mass excision, exploratory laparotomy, Right salpingo oophorectomy, right common iliac nodes sampling and bilateral inguinal LND after 3 months | Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from Nuck EM | R groin tumor recurrence, multiple positive right iliac lymph nodes, one positive right obturator node, several positive right inguinal nodes (radiation therapy) and 2 years after first surgery, left pulmonary metastasis (refused chemo) |

| Sun; 1979 [22] | Excision with hernioplasty and EL | Low grade papillary adenocarcinoma | Local recurrence 3 years after first surgery resection of right lower anterior abdominal wall (inguinal ligament, canal and peritoneum) and groin dissection with exploratory laparotomy |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prodromidou, A.; Pandraklakis, A.; Rodolakis, A.; Thomakos, N. Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010003

Prodromidou A, Pandraklakis A, Rodolakis A, Thomakos N. Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleProdromidou, Anastasia, Anastasios Pandraklakis, Alexandros Rodolakis, and Nikolaos Thomakos. 2021. "Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Diagnostics 11, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010003

APA StyleProdromidou, A., Pandraklakis, A., Rodolakis, A., & Thomakos, N. (2021). Endometriosis of the Canal of Nuck: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Diagnostics, 11(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010003