Discovering, Integrating, and Reinterpreting the Molecular Logic of Life: From Classical Theories of Heredity to an Extended Functional Perspective on the Central Dogma

Abstract

1. Introduction

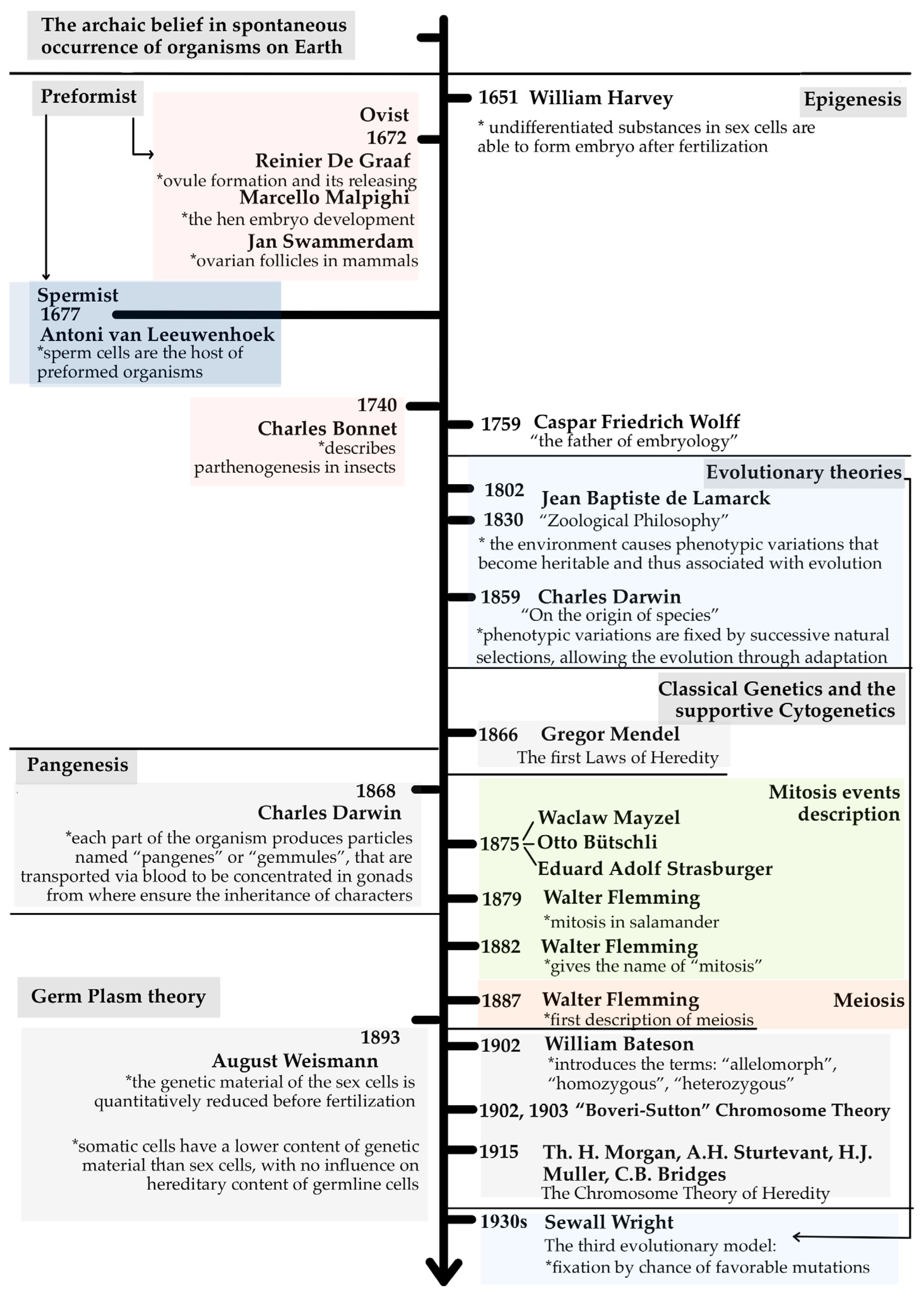

2. Heredity Beginnings: From Archaic Theories to Hereditary Factors

2.1. From Tiny Humans to Gradual Growth: Understanding Early Development Theories

2.2. Heredity in Evolution

2.3. The Genetic Journey: From Mendel’s Laws to Cellular Division and Chromosomes

3. From Particles to Lineage: Pangenesis and Germ Plasm Theories

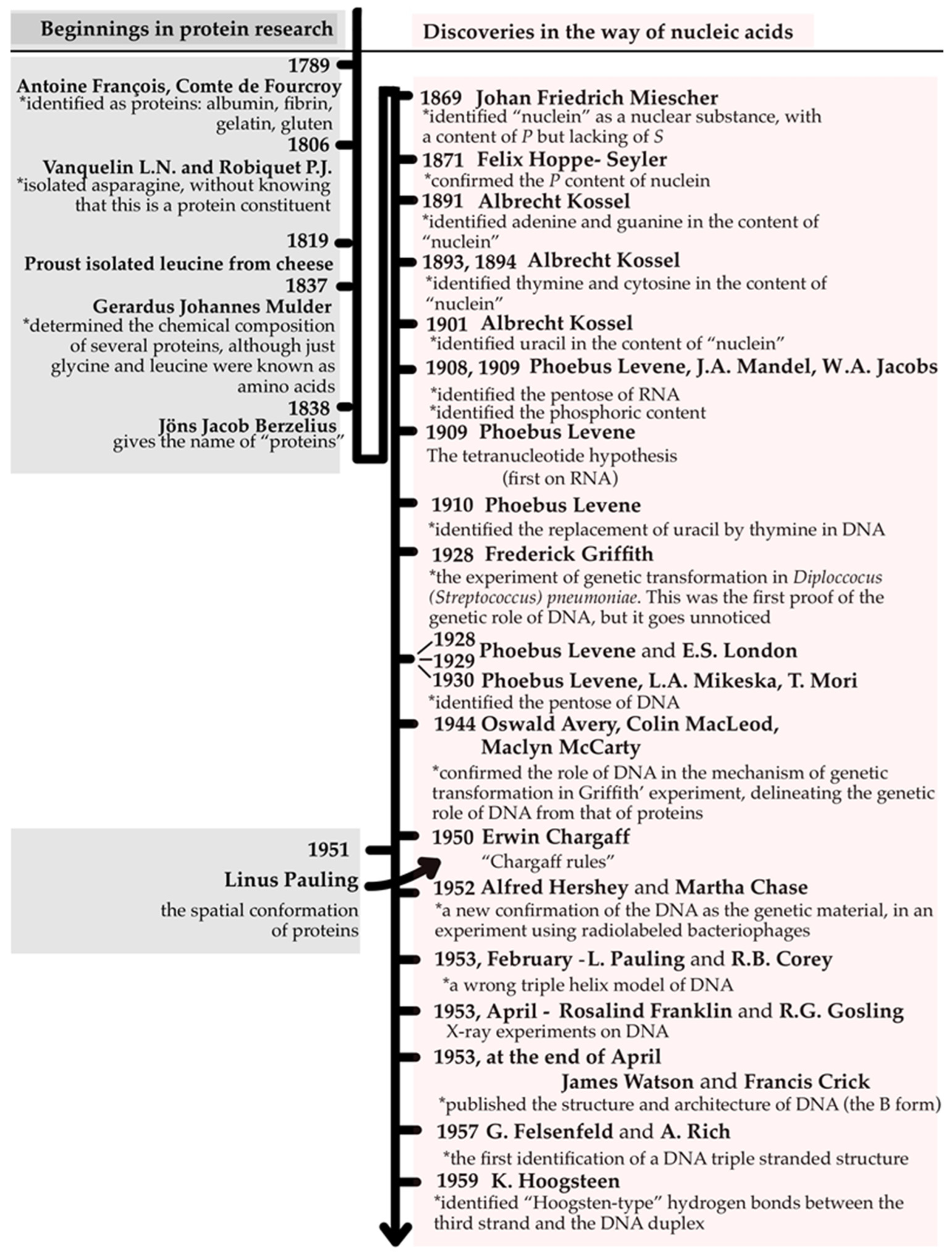

4. The Substrate Dilemma of Heredity: DNA or Proteins?

4.1. Before DNA: Proteins and the Quest to Understand Heredity

4.2. From Griffith to the Double Helix: The Birth of Molecular Genetics

4.3. From Pauling’s Triple Helix to Real Triple and Quadruplex DNA

5. The Exception to the Rule: RNA Can Be the Substrate of Heredity!

5.1. The DNA Provirus Hypothesis and the Dawn of RNA → DNA Information Flow

5.2. The Discovery of Reverse Transcriptase (1970)

5.3. Integration of the Provirus into the Host Genome

5.4. Reverse Transcription, Recombination, and the Protovirus Theory

5.5. RNA-Centric Perspectives on Molecular Information Flow: From Rich’s Early Vision to Modern Evolutionary Implications

6. Ambiguities in Translation: Who Is the Messenger After All?

6.1. Early Clues Linking RNA to Protein Synthesis

6.2. Phage Experiments and the First Glimpse of an Induced RNA

6.3. Gamow, Crick, and the Search for a Decoding Mechanism

6.4. (1961): The Pivotal Year When the Messenger Was Finally Identified

6.5. The Translational Mechanism Becomes Complete

7. Some Diseases Transmission by Means of Proteinaceous Agents Induces a New Confusion About Proteins: Are They the Expression of Heredity or Its Substrate?

7.1. Molecular Basis of Prion Diseases: Beyond the Early Paradox

7.2. Three Mechanisms of Etiology and a Strict Genetic Prerequisite

7.3. Infectivity, Transmission, and the Concept of Protein-Only Propagation

8. From Stable Structures to Jumping Genes in the Genome

9. From Fixed Pathways to Flexible Control: How Epigenetic and Epigenetic-like Factors Shaped the Central Dogma

9.1. Molecular Basis of Epigenetic Control in a Historical Framework: (i) DNA Methylation, (ii) Histone Modifications and Chromatin Remodeling, and (iii) Nucleosome Positioning

9.2. Non-Canonical A- and Z-DNA Forms and Their Epigenetic-like Influence on Gene Expression and Chromatin State

9.3. Non-Coding RNAs in Epigenetic and Epigenetic-like Regulation

9.3.1. Housekeeping Non-Coding RNAs: Constitutive Molecules with Epigenetic-like Effects

9.3.2. Regulatory Non-Coding RNAs: Direct Modifiers of Transcription and Translation

9.4. Epigenetic-like Modifications and Functions of RNA: From Methylation to Catalysis

9.5. Cytoplasmic Inheritance and Its Influence on Nuclear Epigenetic Regulation

10. De Novo Gene Birth and Pseudogenization: Two Faces of the Same Genomic Dynamics

11. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Key Molecular Terms

| DNA | DeoxyriboNucleic Acid; the primary hereditary molecule storing genetic information |

| RNA | RiboNucleic Acid; mediates information transfer and regulatory functions between DNA and proteins |

| A, T, G, C, U | Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, Cytosine, Uracil; nucleotide bases |

| B-DNA | canonical right-handed DNA double helix predominant under physiological conditions |

| A-DNA | alternative right-handed DNA conformation favored by low hydration and certain ionic conditions |

| Z-DNA | left-handed DNA helix stabilized by high ionic strength, negative supercoiling, or CpG methylation |

| nDNA | nuclear DNA; the chromosomal DNA contained within the nucleus |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA; the circular genome located within mitochondria |

| cDNA | complementary DNA; DNA synthesized from an RNA template by reverse transcription |

| dsDNA | double-stranded DNA; the canonical form of DNA composed of two complementary antiparallel nucleotide strands forming a double helix |

| rDNA | recombinant DNA; DNA molecules generated by combining genetic material from different sources, either naturally (e.g., through viral integration or transposition) or experimentally via genetic engineering |

| A-RNA | A-form RNA helix; the right-handed double-helical conformation adopted by RNA molecules and RNA-RNA hybrids |

| dsRNA | double-stranded RNA; an RNA molecule composed of two complementary RNA strands paired by Watson–Crick base pairing and typically adopting an A-form helical structure |

| mRNA | messenger RNA; a single-stranded RNA molecule transcribed from a DNA template |

| tRNA | transfer RNA; a small, structured RNA molecule that functions as an adaptor during protein synthesis |

| rRNA | ribosomal RNA; the structural and catalytic core of the ribosome |

| M-RNA | Messenger RNA (original abbreviation) |

| M1 RNA | the catalytic RNA component of bacterial RNase P |

| ncRNAs | non-coding RNAs; RNA molecules that are transcribed from the genome but do not encode proteins |

| snRNAs | small nuclear RNAs; ncRNAs that are essential components of the spliceosome |

| snoRNAs | small nucleolar RNAs; ncRNAs that primarily localize to the nucleus and that are involved in the post-transcriptional modification and processing of ribosomal RNAs, as well as some snRNAs and tRNAs |

| miRNAs | microRNAs; short ncRNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally |

| siRNAs | small/short interfering RNAs; short double-stranded RNAs that mediate sequence-specific gene silencing through the RNA interference pathway |

| piRNAs | PIWI-interacting RNAs; a class of small ncRNAs that associate specifically with PIWI proteins, a family of Argonaute proteins |

| lncRNAs | long non-coding RNAs; a diverse class of RNA molecules longer than ~200 nucleotides that do not encode proteins |

| sRNAs | small (prokaryotic) non-coding RNAs; small ncRNAs predominantly found in prokaryotes that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level |

| hpRNAs | hairpin RNAs; single-stranded RNA molecules that fold back on themselves to form a stem–loop (hairpin) structure due to internal base pairing, contributing to sequence-specific post-transcriptional gene silencing |

| ceRNAs | competing endogenous RNAs; RNA molecules, such as mRNAs, lncRNAs, circular RNAs, pseudogene transcripts, that regulate gene expression by competing for shared miRNAs |

| mt-rRNAs | mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs; ribosomal RNA molecules encoded by the mitochondrial genome and constituting the structural and catalytic core of mitochondrial ribosomes (mitoribosomes) |

| mt-tRNAs | mitochondrial transfer RNAs; transfer RNA molecules encoded by the mitochondrial genome and required for protein synthesis within mitochondria |

| mt-mRNAs | mitochondrial messenger RNAs; messenger RNA molecules transcribed from the mitochondrial genome and serve as templates for the synthesis of mitochondrially encoded proteins, primarily components of the oxidative phosphorylation system |

| mitomiRs | miRNAs encoded by nuclear genes or mitochondrial genes |

| UTR | UnTranslated Region (of mRNA) |

| RSV | Rous sarcoma virus; an oncogenic retrovirus first identified in chickens, and that carries an RNA genome that is reverse-transcribed into DNA and integrated into the host genome as a provirus, providing key experimental support for extending the Central Dogma to include RNA → DNA information flow |

| TSEs | Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies; they are a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders affecting humans and animals, exemplifying protein-based infectivity, where pathogenic prion conformations propagate by templating misfolding of the normal cellular prion protein, without involvement of nucleic acids |

| PrPC | Prion Protein, C—cellular form; this is the normal isoform of the prion protein, encoded by the PRNP gene and predominantly expressed on the cell surface where it is anchored to the plasma membrane via a GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol) moiety |

| PrPSc | Prion Protein, Scrapie; this is the pathogenic misfolded isoform of the prion protein, derived from the normal cellular prion protein, characterized by a β-sheet-rich conformation, partial resistance to protease digestion, and a strong tendency to aggregate |

| PRNP | Prion Protein gene in humans; this is the gene encoding the human prion protein and that is located on chromosome 20 (20p13) |

| Prnp | Prion Protein gene in mouse; this is the ortholog of the human PRNP gene, located on chromosome 2 |

| PROIN | Proteinaceous Infectious particle (transformed in PRION) |

| PMTs | Post-translational Modifications; these are covalent chemical modifications of proteins that occur after translation, altering protein structure, stability, localization, interaction capacity, and activity |

| GPI | GlycosylPhosphatidylInositol, a glycolipid anchor that covalently attaches certain proteins to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; this is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the selective degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord |

| TEs | Transposable Elements; they are mobile DNA sequences capable of changing their position within a genome |

| Ds | Dissociation element; this is a type of transposable element discovered in maize, known for its ability to move or “jump” within genome |

| Ac | Activator; this is an autonomous DNA transposable element |

| Alu | Alu elements; they are short interspersed nuclear elements that represent the most abundant transposable elements in the human genome |

| DNMTs | DNA MethylTransferases; they are a family of enzymes that catalyze DNA methylation |

| TFs | Transcription Factors; they are DNA-binding proteins that regulate gene expression by controlling the initiation, rate, and specificity of transcription by RNA polymerase |

| HATs | Histone AcetylTransferases; they are enzymes that add acetyl groups to specific lysine residues on histone proteins, primarily within histone tails |

| HDACs | Histone DeACetylases; they are enzymes that remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histone tail, reversing the action of HATs |

| 5mC | 5-methylCytosine; this is a covalent DNA base modification in which a methyl group is added to the 5-carbon of cytosine, most commonly within CpG dinucleotides in eukaryotic genomes |

| SAM | S-Adenosyl Methionine; this is a universal biological methyl-group donor involved in a wide range of methylation reactions in cells |

| Xist RNA | X-inactive specific transcript RNA, a lncRNA that plays a central role in X-chromosome inactivation in female mammals |

| ATRX protein | Alpha-Thalassemia mental Retardation X-linked protein; this is a chromatin-remodeling protein encoded by ATRX gene on the X chromosome |

| PRC2 | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2; this is a multisubunit epigenetic regulator that mediates transcriptional repression through histone modification |

| H3K27 | the 27th amino acid in Histone H3, which as a lysine (written as “K”) |

| HOX | HomeobOX; HOX genes are a highly conserved family of transcription factor-encoding genes that control anterior–posterior body patterning and cell identity during development |

| HOTAIR | HOX Transcript Antisense Intergenic RNA; this is a well-characterized lncRNA that functions as a chromatin-associated regulatory RNA, playing a key role in epigenetic gene silencing |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2; this is a histone methyltransferase and the catalytic core subunit of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), playing a central role in epigenetic gene silencing |

| LSD1 | Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1A; this is a histone demethylase that plays a key role in epigenetic regulation of gene expression by removing methyl groups from specific lysine residues on histone tails |

| H3K4 | the fourth amino acid in Histone H3, which is a lysine |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (process); this is a biological process in which epithelial cells lose their cell–cell adhesion and polarity and acquire mesenchymal characteristics, including enhanced migratory and invasive capacity |

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| Ago | Argonaute; this is a class of highly conserved family of RNA-binding proteins that are central components of RNA-mediated gene silencing pathways |

| H3K9 | the ninth amino acid in Histone H3, which is a lysine |

| TGS | Transcriptional Gene Silencing; this is a regulatory mechanism in which gene expression is repressed at the level of transcription, typically through chromatin modification, rather than by degradation of mRNA after it is produced |

| RISC | RNA-Induced Silencing Complex; this is a multiprotein effector complex that mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) by using small RNAs as a sequence-specific guides to target complementary RNA molecules |

| Su(Ste) | Su(Ste) locus, a Y chromosome linked repetitive locus in Drosophila melanogaster that produces piRNAs complementary to Stellate (Ste) sequences located on the X chromosome |

| PIWI | P-element-Induced Wimpy testis; a subfamily of Argonaute proteins that specifically binds piRNAs (PIWI-interacting RNAs) and that is essential for germline development and fertility |

| PAZ | PIWI-Argonaute-Zwille; this is a conserved RNA-binding domain found in Argonaute and PIWI proteins that specifically binds the 3` end of small RNAs (miRNAs, siRNAs, piRNAs), typically recognizing the two-nucleotide 3` overhang |

| m6A | N6-methylAdenosine; this is a post-transcriptional RNA modification in which a methyl group is added to the nitrogen-6 position of adenosine |

| m5C | 5-methylCytosine; this is a post-transcriptional RNA modification in which a methyl group is added to the carbon-5 position of cytidine |

| m1A | N1-methylAdenosine; this is a post-transcriptional RNA modification in which a methyl group is added to the nitrogen-1 position of adenosine |

| m7G | N7-methylGuanosine; this is a post-transcriptional RNA modification in which a methyl group is added to the nitrogen-7 position of guanosine |

| HNRNP | Heterogeneous Nuclear RiboNucleoProtein; this is a large family of RNA-binding proteins that associate with nascent and processed RNAs, primarily in the nucleus, forming ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes |

| CDS | Coding Sequence; this is the portion of a gene or mRNA that is translated into protein |

| CMD | CDS-m6A Decay; this is a translation-coupled mRNA decay pathway triggered by N6-methyladenosine modifications within the coding sequence |

| YTHDF | YTH Domain Family; this is a family of cytoplasmic m6A reader proteins that recognize N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modifications on RNA and regulate mRNA fate |

| eIF | eukaryotic Initiation Factor; this is a group of proteins that regulate the initiation phase of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells by controlling ribosome recruitment to mRNA |

| METTL | MethylTransferase-Like protein; this is a family of enzymes that catalyze RNA methylation, most prominently N6-methyladenosine (m6A), thereby regulating RNA metabolism and gene expression |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species; these are chemically reactive oxygen-derived molecules that arise as natural by-products of cellular metabolism and function both as signaling molecules and sources of oxidative stress |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide; this is a ubiquitous redox cofactor and metabolic signaling molecule essential for cellular energy metabolism, epigenetic regulation, and stress response |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A; this is a nuclear-encoded DNA-binding protein essential for mitochondrial DNA maintenance, transcription, and packaging |

| NRF-1 | Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1; this is a nuclear transcription factor that coordinates the expression of genes required for mitochondrial biogenesis, respiration, and mitochondrial-nuclear communication |

| α-KG | Alpha-KetoGlutarate; this is a central metabolic intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid cycle that also functions as a key regulator of epigenetic and epigenetic-like processes |

| TET | Ten-Eleven Translocation (enzymes); this is a family of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze active DNA demethylation and play a central role in epigenetic regulation |

| JmjC | Jumonji C (protein domain); this is a conserved protein domain found in histone demethylases that catalyzes the removal of methyl groups from histone lysine residues, playing a central role in chromatin dynamics and epigenetic regulation |

| SIRTs | Sirtuins (enzymes); this is a conserved family of NAD+–dependent deacetylases and ADP-ribosyltransferases that regulate chromatin structure, gene expression, metabolism, stress responses, and aging |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyGuanosine; this is a widely used biomarker of oxidative DNA damage resulting from the oxidation of the guanine base in DNA |

| HMTs | Histone MethylTransferases; this is a class of enzymes that catalyze the transfer of methyl groups to specific lysine or arginine residues on histone proteins, thereby regulating chromatin structure and gene expression |

| HDMs | Histone DeMethylases; this is a class of enzymes that remove methyl groups from methylated histone residues, thereby reversing histone methylation marks and dynamically regulating chromatin structure and gene expression |

| m62A | Dimethylation of Adenosine residues at the N6-position |

| Ψ | Pseudouridine; this is the most abundant post-transcriptional RNA modification formed by isomerization of uridine, in which the uracil base is linked to ribose via carbon-carbon bond instead of the usual nitrogen-carbon bond |

| PUSs | PseudoUridine Synthases; this is a family of RNA-modifying enzymes that catalyze the site-specific conversion of uridine to pseudouridine in RNA molecules |

| RPUSD3, RPUSD4 | RNA PseudoUridine Synthase D3, D4; these are mitochondrial pseudouridine synthases involved in post-transcriptional modification of mitochondrial RNAs |

| MLASA | mitochondrial Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia |

| GULO | L-gulonolactone oxidase (gene) |

References

- Callebaut, M. Historical evolution of preformistic versus neoformistic (epigenetic) thinking in embryology. Belg. J. Zool. 2008, 138, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Poczai, P.; Santiago-Blay, J.A. Chip off the old block: Generation, development, and ancestral concepts of heredity. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 814436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Speybroeck, L.; De Waele, D.; Van de Vijver, G. Theories in early embryology, preformationism, and self-organization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 981, 7–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoglou, A.; Wolfe, C.T. Introduction: Sketches of a conceptual history of epigenesis. Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2018, 40, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarck, J. Recherches Sur L’organisation des Corps Vivans; Chez L’auteur, Maillard; Fayard: Paris, France, 1802. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarck, J.B. Philosophie Zoologique; Baillière: Paris, France, 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species; John Murray: London, UK, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. A new perspective on Darwin’s pangenesis. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2008, 83, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Zhou, X.M.; Zhi, M.X.; Li, X.J.; Wang, Q.L. Darwin’s contribution to Genetics. J. Appl. Genet. 2009, 50, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. Darwin’s pangenesis and molecular medicine. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. The criticism of pangenesis: The years of controversy. Adv. Genet. 2018, 101, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendel, G. Experiments in Plant-Hybridization; Royal Horticultural Society: London, UK, 1866. [Google Scholar]

- Weismann, A. The Germ-Plasm: A Theory of Heredity; Charles Scribner’s & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, W. Zellsubstanz, Kern und Zelltheilung; F.C.W. Vogel: Leipzig, Germany, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Limon, J.; Bartnik, E.; Komender, J. Unjustly forgotten scientist Wacław Mayzel (1847–1916)-co-discoverer of somatic mitosis. J. Appl. Genet. 2021, 62, 639–642, Erratum in J. Appl. Genet. 2024, 65, 645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-024-00863-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröscher, A. Flemming Walther. In Science & Society, in eLS; Walther, F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simunek, M.; Hossfeld, U.; Wissemann, V. ‘Rediscovery’ revised–the cooperation of Erich and Armin von Tschermak-Seysenegg in the context of the ‘rediscovery’ of Mendel’s laws in 1899–1901. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveri, T. Über mehrpolige mitosen als mittel zur analyse des Zellkerns. Verh. Phys.-Med. Ges. Würzburg (NF) 1902, 35, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, W.S. On the morphology of the chromosome group in Brachystola magma. Biol. Bull. 1902, 4, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, W.S. The chromosomes in heredity. Biol. Bull. 1903, 4, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, O.T.; Macleod, C.M.; McCarty, M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus type III. J. Exp. Med. 1944, 79, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Molecular structure of nucleic acids: A structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H. On protein synthesis. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1958, 12, 138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, F. Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temin, H.M.; Mizutani, S. Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase: RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus. Nature 1970, 226, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltimore, D. R Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase: RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of RNA tumor viruses. Nature 1970, 226, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, K.; Grabowski, P.; Zaug, A.; Sands, J.; Gottschling, D.; Cech, T. Self-splicing RNA: Autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena. Cell 1982, 31, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrier-Takada, C.; Gardiner, K.; Marsh, T.; Pace, N.; Altman, S. The RNA moiety of ribonucleases P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell 1983, 35, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B. Novel proteinaceous infection particles cause scrapie. Science 1982, 216, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, B. The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1950, 36, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, R.D. The quantitative separation of purines, pyrimidines, and nucleosides by paper chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 175, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allfrey, V.G.; Faulkner, R.; Mirsky, A.E. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1964, 51, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palade, G.E. A small particulate component of the cytoplasm. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1955, 1, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, M.B.; Stephenson, M.L.; Scott, J.F.; Hecht, L.I.; Zamecnik, P. A soluble acid intermediate in protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 231, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, R.W.; Apgar, J.; Everett, G.A.; Madison, J.T.; Marquisee, M.; Merrill, S.H.; Penswick, J.R.; Zamir, A. Structure of a ribonucleic acid. Science 1965, 147, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, J.L.; Busch, H. Isolation and characterization of uridylic acid-rich 7 S ribonucleic acid of rat liver nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 1968, 243, 6334–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A.; Penman, S. Small molecular weight monodisperse nuclear RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 38, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.R.; Steitz, J.A. Antibodies to small nuclear RNAs complexed with proteins are produced by patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 5495–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestayko, A.W.; Tonato, M.; Busch, H. Low molecular weight RNA associated with 28 s nucleolar RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1970, 47, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, R.; Busch, H. Small nuclear RNAs and RNA processing. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1983, 30, 127–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakin, A.G.; Smith, L.; Fournier, M.J. The RNA World of the nucleolus: Two major families of small RNAs defined by different box elements with related functions. Cell 1996, 86, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, E.S.; Fournier, M.J. The small nucleolar RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 897–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Ballabio, A.; Rupert, J.L.; Lafreniere, R.G.; Grompe, M.; Tonlorenzi, R.; Willard, H.F. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 1991, 349, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockdorff, N.; Ashworth, A.; Kay, G.F.; Cooper, P.; Smith, S.; McCabe, V.M.; Norris, D.P.; Penny, G.D.; Patel, D.; Rastan, S. Conservation of position and exclusive expression of mouse Xist from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 1991, 351, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complemen-tarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, B.; Ha, I.; Ruvkun, G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.Q.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravin, A.A.; Naumova, N.M.; Tulin, A.V.; Vagin, V.V.; Rozovsky, Y.M.; Gvozdev, V.A. Double-stranded RNA-mediated silencing of genomic tandem repeats and transposable elements in the D. melanogaster germline. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, R.E.; Gosling, R.G. The structure of sodium thymonucleate fibres. I. The influence of water content. Acta Crystallogr. 1953, 6, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, F.M.; Jovin, T.M. Salt-induced co-operative conformational change of a synthetic DNA: Equilibrium and kinetic studies with poly (dG-dC). J. Mol. Biol. 1972, 67, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.H.; Quigley, G.J.; Kolpak, F.J.; Crawford, J.L.; van Boom, J.H.; van der Marel, G.; Rich, A. Molecular structure of a left-handed double helical DNA fragment at atomic resolution. Nature 1979, 282, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.L.F.; Zanotto, E.D. On the first patents, key inventions and research manuscripts about glass science & technology. World Pat. Inf. 2016, 47, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Schaeffer, J. Cytogenetics: Plants, Animals, Humans; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, H. The discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, fellows of the Royal Society. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 2004, 58, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, H. Homage to Robert Hooke (1635–1703): New insights from the recently discovered Hooke Folio. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2009, 52, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, N. The unseen world: Reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) ‘concerning little animals’. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, M. Reinier De Graaf (1641–1673) and the Graafian follicle. Gynecol. Surg. 2009, 6, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, M. An amazing 10 years: The discovery of egg and sperm in the 17th century. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2012, 47, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, M.E. W.Harvey’s conception of epigenesis. An organicist reading. Theoria 2021, 36, 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, M.K. Environmental epigenetics and a unified theory of the molecular aspects of evolution: A neo-Lamarckian concept that facilitate neo-Darwinian evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, F. From Darwin’s Origin of Species toward a theory of natural history. F1000Prime Rep. 2015, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Wolf, Y.I. Is evolution Darwinian or/and Lamarckian? Biol. Direct 2009, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics 1931, 16, 97–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S. The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics; Brooklyn Botanic Garden: New York, NY, USA, 1932; pp. 356–366. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, N.H. Sewall Wright on evolution in Mendelian populations and the “Shifting Balance”. Genetics 2016, 202, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J. Disparity, adaptation, exaptation, bookkeeping, and contingency at the genome level. Paleobiology 2005, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.H.; Sturtevant, A.H.; Muller, H.J.; Bridges, C.B. The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA; The Maple Press York: York, PA, USA, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R.A. Has Mendel’s work been rediscovered? Ann. Sci. 1936, 1, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blixt, S. Why didn’t Gregor Mendel find linkage? Nature 1975, 256, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegorsch, W.W. Fischer’s contributions to Genetics and Heredity, with special emphasis on the Gregor Mendel controversy. Biometrics 1990, 46, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorroochurn, P. The Development of Evolutionary Genetics: From Early Ideas on Evolution to the Modern Synthesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Darwin’s pangenesis and certain anomalous phenomena. Adv. Genet. 2018, 102, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.E.; Maamar, M.B.; Skinner, M.K. Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance and the Weismann barrier: The dawn of Neo-Lamarckian theory. J. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.E.; Skinner, M.K. Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of reproductive disease. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 93, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastritis, P.L.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: Daring to ask why proteins interact. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20120835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamm, E.; Harman, O.; Veigl, S.J. Before Watson and Crick in 1953 came Friedrich Miescher in 1869. Genetics 2020, 215, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thess, A.; Hoerr, I.; Panah, B.Y.; Jung, G.; Dahm, R. Historic nucleic acids isolated by Friedrich Miescher contain RNA besides DNA. Biol. Chem. 2021, 402, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, R. Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA. Dev. Biol. 2005, 278, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.E. Albrecht Kossel, a biographical sketch. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1953, 26, 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Levene, P.A.; Jacobs, W.A. Über die Pentose in den Nucleinsäuren (About the pentose in the nucleic acids). Berichte Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1909, 42, 3247–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A. On the biochemistry of nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1910, 32, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; London, E.S. The structure of thymonucleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1929, 83, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; Mikeska, L.A.; Mori, T. On the carbohydrate of thymonucleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1930, 85, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; Mandel, J.A. Über die Konstitution der thymo-nucleinsäure. Berichte Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1908, 41, 1905–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; Jacobs, W.A. Über Inosinsäure (About inosic acid). Berichte Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1909, 42, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A. Yeast nucleic acid. Biochem. Z. 1909, 17, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, R.J. Some aminoacids, peptides and amines in milk, concentrated milks and cheese. J. Dairy. Sci. 1951, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, R.D.; Hill, R.L.; Vaughan, M. The discovery of the amino acid threonine: The work of William C. Rose. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, F. The significance of Pneumococcal types. J. Hyg. 1928, 27, 113–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijkers, G.; Dekker, K.; Berbers, G. Oswald Avery: Pioneer of bacterial vaccines and the first to discover the function of DNA. Cureus 2024, 16, e71465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chargaff, E. Chemical specificity of nucleic acids and mechanism of their enzymatic degradation. Experimentia 1950, 6, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.E.; Gosling, R.G. Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate. Nature 1953, 171, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauling, L.; Corey, R.B. The pleated sheet, a new layer configuration of polypeptide chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1951, 37, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L.; Corey, R.B.; Branson, H.R. The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1951, 37, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D.; Chase, M. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 36, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, A. Rosalind Franklin. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percec, V.; Xiao, Q. The legacy of Rosalind E. Franklin: Landmark contributions to two Nobel Prizes. Chem 2021, 7, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L.; Corey, R.B. A proposed structure for the nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1953, 39, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenfeld, G.; Rich, A. Studies on the formation of two- and three-stranded polyribonucleotides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1967, 26, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogsteen, K. The structure of crystals containing a hydrogen-bonded complex of 1-methylthymine and 9-methyladenine. Acta Cryst. 1959, 12, 822–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Wang, G.; Vasquez, K.M. DNA triple helices: Biological consequences and therapeutic potential. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1117–1130, Erratum in Biochimie 2018, 148, 139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2018.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Alba Ortíz, A.; Vreede, J.; Ensingl, B. Sequence dependence of transient Hoogsteen base pairing in DNA. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, M.; Frederick, C.A.; Wang, A.H.J.; Rich, A. A bifurcated hydrogen-bonded conformation in the d(A•T) base pairs of the DNA dodecamer d(CGCAAATTTGCG) and its complex with distamycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Biochem. 1987, 84, 8385–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broitman, S.L.; Im, D.D.; Fresco, J.R. Formation of the triple-stranded polynucleotide helix, poly (A.A.U). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 5120–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, R.D.; Collier, D.A.; Hanvey, J.C.; Shimizu, M.; Wohlrab, F. The chemistry and biology of unusual DNA structures adopted by oligopurine.oligopyrimidine sequences. FASEB J. 1988, 2, 2939–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, I. Untersuchungen über die Guanylsäure. Biochem. Z. 1910, 26, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. G-Quadruplex DNA and RNA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2035, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco, M.T.; Ferré-D’Amaré, A.R. The emerging structural complexity of G-quadruplex RNAs. RNA 2021, 27, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázda, V.; Hároníková, L.; Liao, J.C.; Fojta, M. DNA and RNA quadruplex-binding proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 17493–17517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, M.; Lipsett, M.N.; Davies, D.R. Helix formation by guanylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1962, 48, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, P.; Wolski, P.; Pańczyk, T. Insights into the molecular structure, stability, and biological significance of non-canonical DNA forms, with a focus on G-quadruplexes and i-motifs. Molecules 2024, 29, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.R. G-quartet structures in telomeric DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1994, 23, 703–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.T.; Mergny, J.L. Human telomeric DNA: G-quadruplex, i-motif and Watson–Crick double helix. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 4618–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, P.; Nieszporek, K.; Panczyk, T. G-quadruplex and i-motif structures within the telomeric DNA duplex. A molecular dynamics analysis of protonation states as factors affecting their stability. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Assi, H.; El-Khoury, R.; González, C.; Damha, M.J. 2′-Fluoroarabinonucleic acid modification traps G-quadruplex and i-motif structures in human telomeric DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 11535–11546, Erratum in Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12055. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, H.; Zhou, X. G-quadruplexes in neurobiology and virology: Functional roles and potential therapeutic approaches. JACS Au 2021, 1, 2146–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Komiyama, M. G-quadruplexes in human telomere: Structures, properties, and applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A. On the problems of evolution and biochemical information transfer. In Horizons in Biochemistry; Kasha, M., Pullman, B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, N. The RNA World: 4,000,000,050 years old. Life 2015, 5, 1583–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rous, P. A sarcoma of the fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumor cells. J. Exp. Med. 1911, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, L.V.; Crawford, E.M. The properties of Rous sarcoma virus purified by density gradient centrifugation. Virology 1961, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, W.E.; Varmus, H.E.; Garapin, A.C.; Bishop, J.M. DNA of Rous sarcoma virus: Its nature and significance. Science 1972, 175, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temin, H.M. Nature of the provirus of Rous sarcoma. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1964, 17, 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, E.; Franklin, R.M.; Shatkin, A.J.; Tatum, E.L. Action of actinomycin D on animal cells and viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1962, 48, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temin, H.M. Genetic and possible biochemical mechanisms in viral carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1966, 26, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger, D.; Temin, H.M. Light inactivation of focus formation by chicken embryo fibroblasts infected with avian sarcoma virus in the presence of 5-bromodeoxyuridine. Nature 1970, 228, 622–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kates, J.R.; McAuslan, B.R. Poxvirus DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967, 58, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munyon, W.; Paoletti, E.; Grace, J.T., Jr. RNA polymerase activity in purified infections vaccinia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967, 58, 2280–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsa, J.; Graham, A.F. Reovirus: RNA polymerase activity in purified virions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1968, 33, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, A.J.; Sipe, J.D. RNA polymerase activity in purified reoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1968, 61, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, J.P.; Garapin, A.C.; Levinson, W.E.; Quintrell, N.; Fanshier, L.; Bishop, J.M. DNA polymerase of Rous sarcoma virus: Delineation of two reactions with actinomycin. Nature 1970, 228, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, J.M. 50th anniversary of the discovery of reverse transcriptase. Mol. Biol. Cell 2021, 32, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temin, H.M.; Baltimore, D. RNA-directed DNA synthesis and RNA tumor viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1972, 17, 129–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, S.; Temin, H.M.; Kodama, M.; Wells, R.T. DNA ligase and exonuclease activities in virions of Rous sarcoma virus. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 230, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.M.; Varmus, H.E. The molecular biology of RNA tumor viruses. In Cancer, a Comprehensive Treatise 2; Becker, F.F., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.M. The molecular biology of RNA tumor viruses: A Physician’s guide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980, 303, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, D.W.; Duesberg, P.H. Retroviral recombination during reverse transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 2052–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temin, H.M. The protovirus hypothesis: Speculations on the significance of RNA-directed DNA synthesis for normal development and for carcinogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1971, 46, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, S.; Temin, H.M. Endogenous RNA synthesis in required for endogenous DNA synthesis by reticuloendotheliosis virus virions. In Fundamental Aspects of Neoplasia; Gottlieb, A.A., Plescia, O.J., Bishop, D.H.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, S.; Temin, H.M. An RNA polymerase activity in purified virions of avian reticuloenditheliosis viruses. J. Virol. 1976, 19, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, J.E.; Young, R.A. An RNA-centric view of transcription and genome organization. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 3627–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Campos, C.; Lanz-Mendoza, H.; Cime-Castillo, J.A.; Peralta-Zaragoza, Ó.; Madrid-Marina, V. RNA through time: From the origin of life to therapeutic frontiers in transcriptomics and epitranscriptional medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshavsky, A. Discovering the RNA double helix and hybridization. Cell 2006, 127, 1295–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A.; Watson, J. Physical studies on ribonucleic acid. Nature 1954, 173, 995–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Watson, J.D. Some relations between DNA and RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1954, 40, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A.; Davies, D.R. A new two-stranded helical structure: Polyadenylic acid and polyuridylic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 3548–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lee, T.; Dziubla, T.; Pi, F.; Guo, S.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Haque, F.; Liang, X.J.; Guo, P. RNA as a stable polymer to build controllable and defined nanostructures for material and biomedical applications. Nano Today 2015, 10, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J. The persistent contributions of RNA to eukaryotic gen(om)e architecture and cellular function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseltine, W.A.; Patarca, R. The RNA revolution in the Central Molecular Biology Dogma evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cech, T.R. The RNA Worlds in context. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a006742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H. The origin of the genetic code. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 38, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgel, L.E. Evolution of the genetic apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 38, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woese, C. The genetic code. In The Genetic Code; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, W. The RNA World. Nature 1986, 319, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacek, N.; Gaynor, M.; Yassin, A.; Mankin, A.S. Ribosomal peptidyl transferase can withstand mutations at the putative catalytic nucleotide. Nature 2001, 411, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunk, C.F.; Marshall, C.R. Opinion: The key steps in the origin of life to the formation of the eukaryotic cell. Life 2024, 14, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaran, N. How the discovery of ribozymes cast RNA in the roles of both chicken and egg in origin-of-life theories. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. C Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 43, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.; Mohan, S.; Kalahar, B.K.; Williams, L.D. Peeling the onion: Ribosomes are ancient molecular fossils. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.S.; Bernier, C.R.; Hsiao, C.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Waterbury, C.C.; Stepanov, V.G.; Harvey, S.C.; Fox, G.E.; Wartell, R.M.; et al. Evolution of the ribosome at atomic resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10251–10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J.C.; Hud, N.V.; Williams, L.D. The ribosome challenge to the RNA World. J. Mol. Evol. 2015, 80, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Genetic implications of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature 1953, 171, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, J.; Deamer, D.; Sandford, S.; Allamandola, L. Self-assembling amphiphilic molecules: Synthesis in simulated interstellar/precometary ices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, J.P.; Lazcano, A.; Miller, S.L. The roads to and from the RNA World. J. Theor. Biol. 2003, 222, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, A. The RNA world: Piecing together the historical development of a hypothesis. Metode Sci. Stud. J. 2016, 6, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.A. Epigenetic control of mobile DNA as an interface between experience and genome change. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersson, T. The relation between nucleic acid and protein synthesis. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1947, 1, 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, A.; Vendrely, R. Sur le role possible des deux acides nucléiques dans la cellule vivante. Experientia 1947, 3, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeener, R.; Szafarz, R. Relation between the rate of renewal and the intracellular localization of ribonucleic acid. Arch. Biochem. 1950, 26, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, A.D. Nucleic acid economy in bacteria infected with bacteriophage T2. II. Phage precursor nucleic acid. J. Gen. Physiol. 1953, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkin, E.; Astrachan, L. Phosphorus incorporation in Escherichia coli ribonucleic acid after infection with bacteriophage T2. Virology 1956, 2, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamow, G. Possible relation between deoxyribonucleic acid and protein structure. Nature 1954, 173, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillen, K.; Roberts, R.B.; Britten, R.J. Synthesis of nascent protein by ribosomes in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1959, 45, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.H.C. On Degenerate Templates and the Adaptor Hypothesis: A Note for the RNA Tie Club. 1955. Available online: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X73 (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Hoagland, M.B.; Zamecnik, P.C.; Stephenson, M.L. Intermediate reactions in protein biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1957, 24, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, M.B.; Comly, L.T. Interaction of soluble ribonucleic acid and microsomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1960, 46, 1554–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.B. Microsomal particles and protein synthesis. In The First Symposium of the Biophysical Society; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, H.; Nirenberg, M.W. The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E.coli upon RNA prepared from ribosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1961, 4, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Monod, J. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1961, 3, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S.; Jacob, F.; Meselson, M. An unstable intermediate carrying information from genes to ribosomes for protein synthesis. Nature 1961, 190, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, F.; Hiatt, H.; Gilbert, W.; Kurland, C.G.; Risebrough, R.W.; Watson, J.D. Unstable ribonucleic acid revealed by pulse labelling of Escherichia coli. Nature 1961, 190, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardee, A.B.; Jacob, F.; Monod, J. The genetic control and cytoplasmatic expression of “induncibility” in the synthesis of β-galactosidase by E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1959, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, M. Crick’s Adaptor Hypothesis and the discovery of transfer RNA: Experiment surpassing theoretical prediction. PTPBio 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.S. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature 1967, 215, 1043–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiolini, I.; Saverioni, D.; Parchi, P. Prion protein misfolding, strains, and neurotoxicity: An update from studies on Mammalian prions. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 2013, 910314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Pham, N.; Yu, S.; Li, C.; Wong, P.; Chang, B.; Kang, S.C.; Biasini, E.; Tien, P.; Harris, D.A.; et al. Human prion proteins with pathogenic mutations share common conformational changes resulting in enhanced binding to glycosaminoglycans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7546–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, S.; Lloyd, S.; Collinge, J. Genetic factors in mammalian prion diseases. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2019, 53, 117–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, B.S.; Shetty, S.; Elkasaby, M. Genetic aspects of human prion diseases. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1003056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitechurch, B.C.; Welton, J.M.; Collins, S.J.; Lawson, V.A. Prion diseases. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 15, 335–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritzkow, S.; Gorski, D.; Ramirez, F.; Soto, C. Prion dissemination through the environment and medical practices: Facts and risks for human health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, 0005919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, D.L.; Barria, M.A. Prion diseases: A unique transmissible agent or a model for neurodegenerative diseases? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Villanueva, J.F.; Díaz-Molina, R.; García-González, V. Protein folding and mechanisms of proteostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17193–17230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Satani, N. The intricate mechanisms of neurodegeneration in prion diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, B.M.; Murdoch, G.K. Genetics of prion disease in cattle. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2015, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thellung, S.; Corsaro, A.; Dellacasagrande, I.; Nizzari, M.; Zambito, M.; Florio, T. Proteostasis unbalance in prion diseases: Mechanisms of neurodegeneration and therapeutic targets. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 966019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, G.G.; Budka, H. Molecular pathology of human prion diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 976–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charco, J.M.; Eraña, H.; Venegas, V.; García-Martínez, S.; López-Moreno, R.; González-Miranda, E.; Pérez-Castro, M.Á.; Castilla, J. Recombinant PrP and its contribution to research on transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Pathogens 2017, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C. Transmissible proteins: Expanding the prion heresy. Cell 2012, 149, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büeler, H.; Fischer, M.; Lang, Y.; Bluethmann, H.; Lipp, H.P.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B.; Aguet, M.; Weissmann, C. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature 1992, 356, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Katamine, S.; Nishida, N.; Moriuchi, R.; Shigematsu, K.; Sugimoto, T.; Nakatani, A.; Kataoka, Y.; Houtani, T.; Shirabe, S.; et al. Loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in aged mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Nature 1996, 380, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusiner, S.B. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13363–13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabbott, N.A. How do PrPSc prions spread between host species, and within hosts? Pathogens 2017, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, M.D.; Reid, C. A brief history of prions. FEMS Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, ftv087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberski, P.P. Historical overview of prion diseases: A view from afar. Folia Neuropathol. 2012, 50, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pattison, I.H.; Jones, K.M. The possible nature of the transmissible agent of scrapie. Vet. Rec. 1967, 80, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, T.; Cramp, W.A.; Haig, D.A.; Clarke, M.C. Does the agent of scrapie replicate without nucleic acid? Nature 1967, 214, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquatella-Tran Van Ba, I.; Imberdis, T.; Perrier, V. From prion diseases to prion-like propagation mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Cell Bio 2013, 2013, 975832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C. Prion hypothesis: The end of the controversy? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.S.; Besnier, L.; Morel, E.; Rousset, M.; Thenet, S. Roles of the cellular prion protein in the regulation of cell-cell junctions and barrier function. Tissue Barriers 2013, 1, e24377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarava, N.; Chang, J.C.; Molesworth, K.; Baskakov, I.V. Posttranslational modifications define course of prion strain adaptation and disease phenotype. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4382–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otvos, L., Jr.; Cudic, M. Post-translational modifications in prion proteins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2002, 3, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymenidou, M.; Cleveland, D.W. The seeds of neurodegeneration: Prion-like spreading in ALS. Cell 2011, 147, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polymenidou, M.; Cleveland, D.W. Prion-like spread of protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnataro, D. Attempt to untangle the prion-like misfolding mechanism for neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, S. Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20198–20199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanov, A.; Gao, Y.; Naqvi, N.I.; Parinov, S. Trans-kingdom transposition of the maize dissociation element. Genetics 2006, 174, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Brutnell, T.P. The activator/dissociation transposable elements comprise a two-component gene regulatory switch that controls endogenous gene expression in maize. Genetics 2011, 187, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.P.; Zuo, T.; Peterson, T. Transposon-induced inversions activate gene expression in the maize pericarp. Genetics 2021, 218, iyab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.; Han, K. Transposable elements: No more ‘Junk DNA’. Genomics Inform. 2012, 10, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Perkins, M.H.; Novaes, L.S.; Xu, T.; Chang, H. Advances in transposable elements: From mechanisms to applications in mammalian genomics. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1290146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, Y.; Semba, K.; Watanabe, S.; Ishikawa, K. Random insertion reporter gimmicks powered by cut-and-paste DNA transposons. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgel, L.E.; Crick, F.H. Selfish DNA: The ultimate parasite. Nature 1980, 284, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, W.F.; Sapienza, C. Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature 1980, 284, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosius, J.; Gould, S.J. On “genomenclature”: A comprehensive (and respectful) taxonomy for pseudogenes and other “junk DNA”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10706–10710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batzer, M.A.; Deininger, P.L. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, D.J. Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. Trends Genet. 1989, 5, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Jiang, N.; Wing, R.A.; Jiang, J.; Jackson, S.A. Transposons play an important role in the evolution and diversification of centromeres among closely related species. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrajab, F.; Hekmatimoghaddam, S. Transposable elements, contributors in the evolution of organisms (from an arms race to a source of raw materials). Heliyon 2021, 7, e06029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoth, M.; Jensen, S.; Brasset, E. The intricate evolutionary balance between transposable elements and their host: Who will kick at goal and convert the next try? Biology 2022, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Ghatage, T.; Bhan, S.; Lahane, G.P.; Dhar, A.; Kumar, R.; Pandita, R.K.; Bhat, K.M.; Ramos, K.S.; Pandita, T.K. Role of transposable elements in genome stability: Implications for health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. The frailty of adaptive hypotheses for the origins of organismal complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8597–8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, A.F.; Gregory, T.R. The case for junk DNA. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamurli, G.; Liew, A.Q.X.; Tee, W.W.; Pervaiz, S. Interplay between epigenetics, senescence and cellular redox metabolism in cancer and its therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2024, 78, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossi, L.; Castagna, C.; Merighi, A. An overview of the epigenetic modifications in the brain under normal and pathological conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes. Dev. 2002, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.L.; Kouzarides, T.; Shiekhattar, R.; Shilatifard, A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes. Dev. 2009, 23, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Friso, S. Epigenetics: A new bridge between nutrition and health. Adv. Nutr. 2010, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.P. Epigenetics: Principles and practice. Dig. Dis. 2011, 29, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E.; Nolan, C. Epigenetics and gene expression. Heredity 2010, 105, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Grzenda, A.; Lomberk, G.; Ou, X.M.; Cruciani, R.A.; Urrutia, R. Epigenetics: A promising paradigm for better understanding and managing pain. J. Pain. 2013, 14, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, R.; Pugh, J.E. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science 1975, 187, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compere, S.J.; Palmiter, R.D. DNA methylation controls the inducibility of the mouse metallothionein-I gene lymphoid cells. Cell 1981, 25, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, Y.; Robertson, K.D. DNA methylation: Superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes. Cancer 2011, 2, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.S.; Shin, W.J.; Lee, J.E.; Do, J.T. CpG and non-CpG methylation in epigenetic gene regulation and brain function. Genes 2017, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, O.S.; Sant, K.E.; Dolinoy, D.C. Nutrition and epigenetics: An interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, K.P.; Lein, P.J. DNA methylation: A mechanism linking environmental chemical exposures to risk of autism spectrum disorders? Environ. Epigenetics 2016, 2, dvv012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenisch, R.; Bird, A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 245–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Kim, J.M.; Matsunaga, W.; Saze, H.; Matsui, A.; Endo, T.A.; Harukawa, Y.; Takagi, H.; Yaegashi, H.; Masuta, Y.; et al. A stress-activated transposon in Arabidopsis induces transgenerational abscisic acid insensitivity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zou, L.H.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, B.; Yu, L.; Zhou, M. Abiotic stress-induced DNA methylation in transposable elements and their transcripts reveals a multi-layered response in Moso bamboo. Ind. Crop Prod. 2024, 210, 118108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, E.; Zambelli, A.; Araniti, F.; Greco, E.; Chiappetta, A.; Bruno, L. Unravelling the epigenetic code: DNA methylation in plants and its role in stress response. Epigenomes 2024, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backs, J.; Olson, E.N. Control of cardiac growth by histone acetylation/deacetylation. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.T.; Oh, S.; Ro, D.H.; Yoo, H.; Kwon, Y.W. The key role of DNA methylation and histone acetylation in epigenetics of atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2020, 9, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Crossing epigenetic frontiers: The intersection of novel histone modifications and diseases. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, R.D. Chromatin structure: A repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science 1974, 184, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, R.D.; Stryer, L. Statistical distributions of nucleosomes: Nonrandom locations by a stochastic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 6677–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, R.D.; Lorch, Y. Chromatin structure and transcription. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1992, 8, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Lu, Y.; Tan, S.; Li, R.; Gao, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y. Nucleosome-omics: A perspective on the epigenetic code and 3D genome landscape. Genes 2022, 13, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordog, T.; Syed, S.A.; Hayashi, Y.; Asuzu, D.T. Epigenetics and chromatin dynamics: A review and a paradigm for functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012, 24, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, K.A.; Gould, C.M.; Du, Q.; Skvortsova, K.; Song, J.Z.; Maddugoda, M.P.; Achinger-Kawecka, J.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S.J.; Taberlay, P.C. Integrated epigenomic analysis stratifies chromatin remodellers into distinct functional groups. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubova, E.A.; Strelnikov, I.A. Experimental detection of conformational transitions between forms of DNA: Problems and prospects. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1053–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every, A.E.; Russu, I.M. Influence of magnesium ions on spontaneous opening of DNA base pairs. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 7689–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Q. Assessing B-Z DNA transitions in solutions via infrared spectroscopy. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanczyc, P. Role of alkali cations in DNA-thioflavin T interaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 7520–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serec, K.; Babić, S.B.; Tomić, S. Magnesium ions reversibly bind to DNA double stranded helix in thin films. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 268, 120663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, A.E. DNA helix: The importance of being GC-rich. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 1838–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.; Mukherjee, A. Understanding B-DNA to A-DNA transition in the right-handed DNA helix: Perspective from a local to global transition. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2017, 128, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, T.; Kuwabara, S.; Mashimo, S.; Yagihara, S. Dielectric study on hydration of B-, A-, and Z-DNA. Biopolymers 1990, 30, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, A. The discovery of the DNA double helix. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 335, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harteis, S.; Schneider, S. Making the bend: DNA tertiary structure and protein-DNA interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12335–12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Zhao, L.; Zewail, A.H. Water at DNA surfaces: Ultrafast dynamics in minor groove recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8113–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, W.C.; Boger, D.L. Sequence-selective DNA recognition: Natural products and nature’s lessons. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, S.; Fedele, M.; Secco, L.; Ingo, A.M.D.; Sgarra, R.; Manfioletti, G. Binding to the other side: The AT-hook DNA-binding domain allows nuclear factors to exploit the DNA minor groove. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudler, E.; Mustaev, A.; Goldfarb, A.; Lukhtanov, E. The RNA–DNA hybrid maintains the register of transcription by preventing backtracking of RNA polymerase. Cell 1997, 89, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KIreeva, M.; Trang, C.; Matevosyan, G.; Turek-Herman, J.; Chasov, V.; Lubkowska, L.; Kashlev, M. RNA-DNA and DNA-DNA base-pairing at the upstream edge of the transcription bubble regulate translocation of RNA polymerase and transcription rate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 5764–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, J.B.; Nichols, P.J.; Henen, M.A.; Vicens, Q.; Vögeli, B. Structure and formation of Z-DNA and Z-RNA. Molecules 2023, 28, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harp, J.M.; Coates, L.; Sullivan, B.; Egli, M. Water structure around a left-handed Z-DNA fragment analyzed by cryo neutron crystallography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 4782–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacolla, A.; Vasquez, K.M.; Wells, R.D. DNA Secondary Structure. In Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Lennarz, W.J., Lane, M.D., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 142–148. ISBN 9780123786319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Christensen, L.A.; Vasquez, K.M. Z-DNA-forming sequences generate large-scale deletions in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2677–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makus, Y.V.; Ashniev, G.A.; Orlov, A.V.; Nikitin, P.I.; Zaitseva, Z.G.; Orlova, N.N. Enrichment of Z-DNA-forming sequences within super-enhancers: A computational and population-based study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, A.; Karandur, D.; Bansal, M. Small local variations in B-form DNA lead to a large variety of global geometries which can accommodate most DNA-binding protein motifs. BMC Struct. Biol. 2009, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il’icheva, I.A.; Vlasov, P.K.; Esipova, N.G.; Tumanyan, V.G. The intramolecular impact to the sequence specificity of B→A transition: Low energy conformational variations in AA/TT and GG/CC steps. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 27, 667–693, Erratum in J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 27, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothe, J.R.; Lowenhaupt, K.; Al-Hashimi, H.M. Incorporation of CC steps into Z-DNA: Interplay between B-Z junction and Z-DNA helical formation. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 6871–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Subramani, V.K.; Kim, K.K. Z-DNA in the genome: From structure to disease. Biophys. Rev. 2019, 11, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenburg, S.; Koch-Nolte, F.; Rich, A.; Haag, F. A polymorphic dinucleotide repeat in the rat nucleolin gene forms Z-DNA and inhibits promoter activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8985–8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.T.; Lu, X.J.; Galindo-Murillo, R.; Gumbart, J.C.; Kim, H.D.; Cheatham, T.E., 3rd; Harvey, S.C. Transitions of double-stranded DNA between the A- and B-forms. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 8449–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temiz, N.A.; Donohue, D.E.; Bacolla, A.; Luke, B.T.; Collins, J.R. The role of methylation in the intrinsic dynamics of B- and Z-DNA. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jung, H.J.; Hong, S.C. Z-DNA as a tool for nuclease-free DNA methyltransferase assay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Hwang, W. Effect of methylation on local mechanics and hydration structure of DNA. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 1791–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bure, I.V.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Kuznetsova, E.B. Histone modifications and non-coding RNAs: Mutual epigenetic regulation and role in pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.W.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Kang, C.S. Non-coding RNAs as regulators in epigenetics. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, M.; Erdmann, V.A.; Barciszewski, J. Noncoding regulatory RNAs database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F.; Vendeix, F.A.; Graham, W.D. tRNA’s wobble decoding of the genome: 40 years of modification. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 366, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Khusainov, I.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. Novel base-pairing interactions at the tRNA wobble position crucial for accurate reading of the genetic code. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.X.; Li, J.; Xiong, Q.P.; Li, H.; Wang, E.D.; Liu, R.J. Position 34 of tRNA is a discriminative element for m5C38 modification by human DNMT2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 13045–13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, E.K.; Martinez, N.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Regulation and function of RNA pseudouridylation in human cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020, 54, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzo, M.; Galbiati, A.; Treré, D.; Montanaro, L. The importance of being (slightly) modified: The role of rRNA editing on gene expression control and its connections with cancer. BBA–Rev. Cancer 2016, 1866, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, E.J.; Steitz, J.A. Three novel functional variants of human U5 small nuclear RNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992, 12, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Mu, J.C.; Ackerman, S.L. Mutation of a U2 snRNA gene causes global disruption of alternative splicing and neurodegeneration. Cell 2012, 148, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, W.; Sudharshan, S.J.; Kafle, S.; Zennadi, R. SnoRNAs: Exploring their implication in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, M.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhang, C. Small nucleolar RNAs: Biological functions and diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terns, M.P.; Terns, R.M. Small nucleolar RNAs: Versatile trans-acting molecules of ancient evolutionary origin. Gene Expr. 2002, 10, 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K. Unlocking the life code: A review of SnoRNA functional diversity and disease relevance. Cell Commun. Signal 2025, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabin, B.V.; Gubar, L.V.; Seeger, B.; Pfeiffer, J.; Handel, S.; Robeck, T.; Karpova, E.; Rozhdestvensky, T.S.; Brosius, J. Deletion of the MBII-85 snoRNA gene cluster in mice results in postnatal growth retardation. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolin-Cavaillé, M.L.; Cavaillé, J. The SNORD115 (H/MBII-52) and SNORD116 (H/MBII-85) gene clusters at the imprinted Prader–Willi locus generate canonical box C/D snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6800–6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S.B.; Schwartz, S.; Miller, J.L.; Driscoll, D.J. Prader–Willi syndrome. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xue, Y. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in epigenetic regulation. Sci. China Life Sci. 2016, 59, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Chou, M.Y.; Inouye, M. A unique mechanism regulating gene expression: Translational inhibition by a complementary RNA transcript (micRNA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 1966–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delihas, N. Discovery and characterization of the first non-coding RNA that regulates gene expression, micF RNA: A historical perspective. World J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 6, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Chang, C.P. Long non-coding RNA and chromatin remodeling. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrand, P.O.; Vennin, C.; Le Bourhis, X.; Adriaenssens, E. The role of long non-coding RNAs in genome formatting and expression. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ding, X.P.; Wang, X. Mechanism of long noncoding RNAs as transcrip-tional regulators in cancer. RNA Biol. 2020, 17, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by long noncoding RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3723–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.L.; Bhan, A.; Mandal, S.S. HOTAIR beyond repression: In protein degradation, inflammation, DNA damage response, and cell signaling. DNA Repair 2021, 105, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantile, M.; Di Bonito, M.; Tracey De Bellis, M.; Botti, G. Functional interaction among lncRNA HOTAIR and microRNAs in cancer and other human diseases. Cancers 2021, 13, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicone, L.; Marchetti, A.; Cicchini, C. The lncRNA HOTAIR: A pleiotropic regulator of epithelial cell plasticity. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Cai, Q.; He, P.; Li, F.; Chen, Q. LncRNA TUG1 repressed angiogenesis by promoting the ubiquitination of HuR and inhibiting its nuclear translocation in cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2413333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. 2024 Nobel Prize awarded for work on microRNAs. Lancet 2024, 404, 1507–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Rameshwar, P.; Etchegaray, J.P. Non-coding RNAs as mediators of epigenetic changes in malignancies. Cancers 2020, 12, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K.; Magoola, M. MicroRNA Nobel Prize: Timely recognition and high anticipation of future products—A prospective analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, E.; Aloisio, A.; Scicchitano, S.; Bond, H.M.; Mesuraca, M. Regulatory role of microRNAs targeting the transcription co-Factor ZNF521 in normal tissues and cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotto, C.; Cogoni, C.; Zardo, G. MicroRNA in control of gene expression: An overview of nuclear functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; De Marinis, E.; Gentile, M.; Nervi, C.; Grignani, F. Nuclear miRNAs: Gene regulation activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisseur, M.; Kwapisz, M.; Morillon, A. Pervasive transcription—Lessons from yeast. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1889–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhya, S.; Gottesman, M. Promoter occlusion: Transcription through a promoter may inhibit its activity. Cell 1982, 29, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.R.; Lomedico, P.T.; Ju, G. Transcriptional interference in avian retroviruses—Implications for the promoter insertion model of leukaemogenesis. Nature 1984, 307, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, J.A.; Laprade, L.; Winston, F. Intergenic transcription is required to repress the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SER3 gene. Nature 2004, 429, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, S.; Pastori, C.; Magistri, M.; Carbone, G.M.; Catapano, C.V. Promoter-specific transcriptional interference and c-myc gene silencing by siRNAs in human cells. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazed, D. Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature 2009, 457, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Chekanova, J.A. Small RNAs: Essential regulators of gene expression and defenses against environmental stresses in plants. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 7, 356–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Villeneuve, L.M.; Morris, K.V.; Rossi, J.J. Argonaute-1 directs siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006, 13, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]