Visual Large Language Models in Radiology: A Systematic Multimodel Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Hallucinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

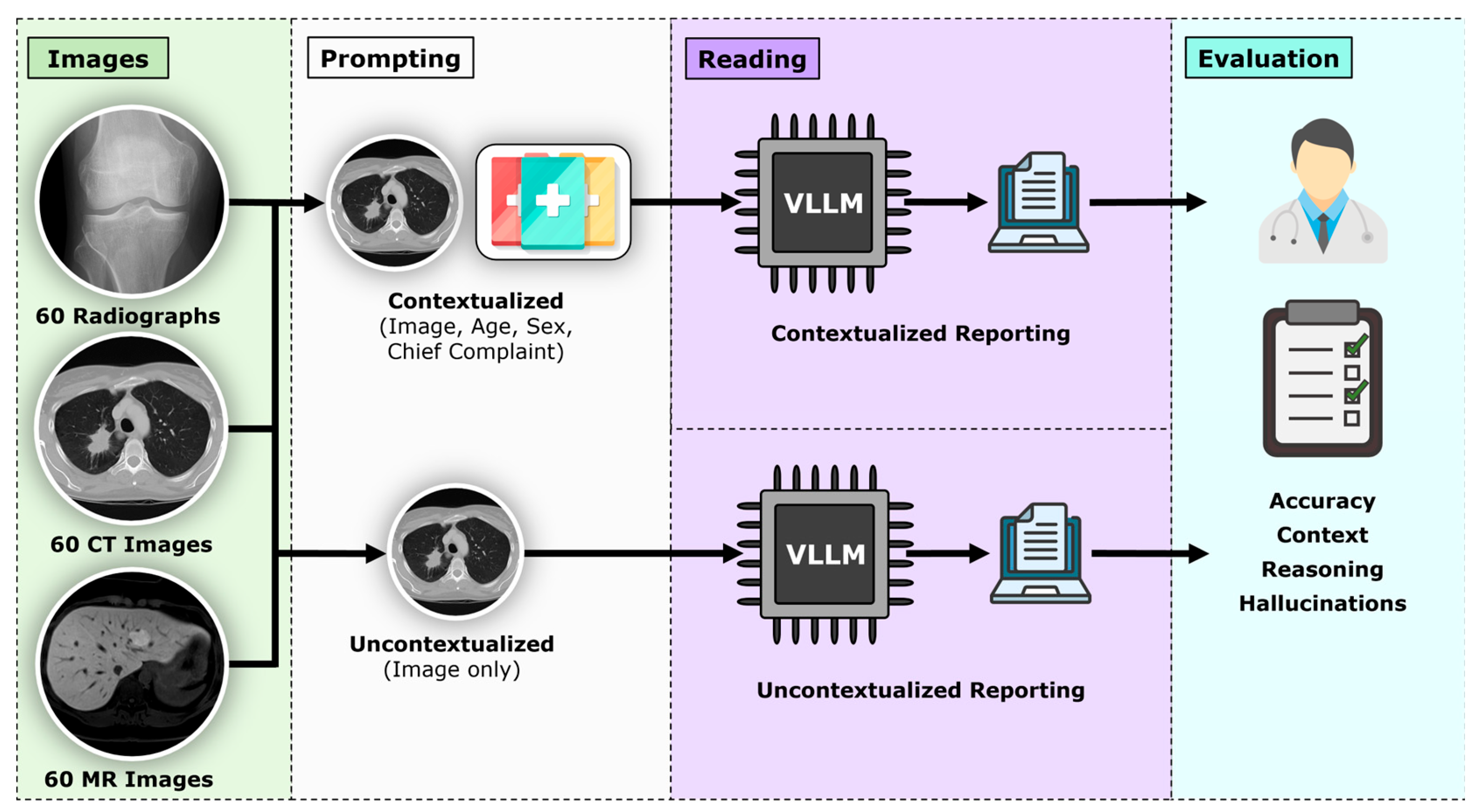

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Dataset and Case Selection

2.3. Models Evaluated

- •

- ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA);

- •

- Claude Sonnet 3.7 (Anthropic, San Francisco, CA, USA);

- •

- Gemini 2.0 (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA);

- •

- Perplexity AI (Perplexity Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA);

- •

- Google Vision AI (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA);

- •

- LLaVA-1.6 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA);

- •

- LLaVA-Med-v1.5 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

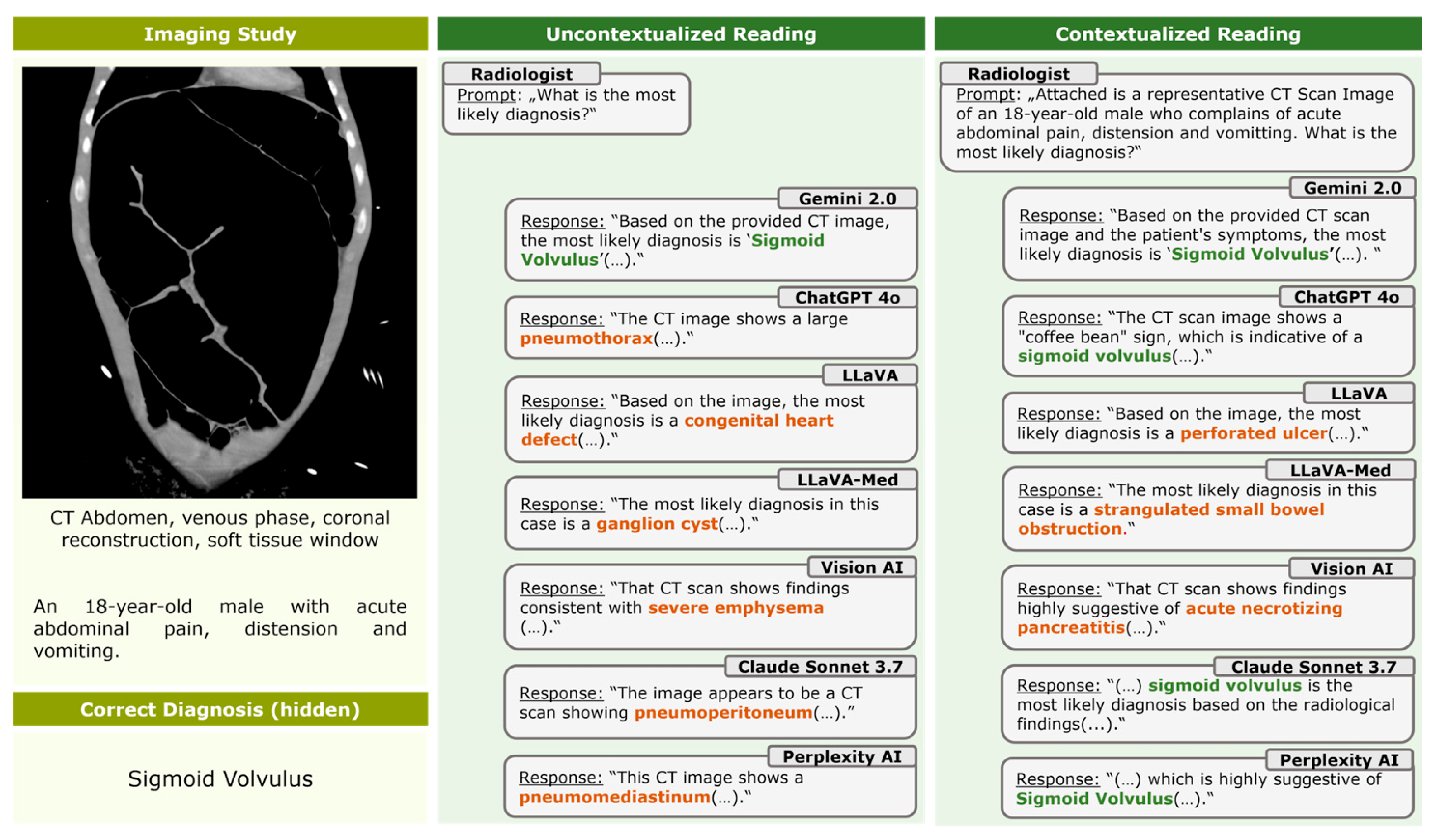

2.4. Prompting Framework

“This request is for a retrospective research study conducted by healthcare professionals. Please answer directly; no clinical recommendations are required.”

2.5. Outcome Metrics

2.6. Statistical and Power Analysis

3. Results

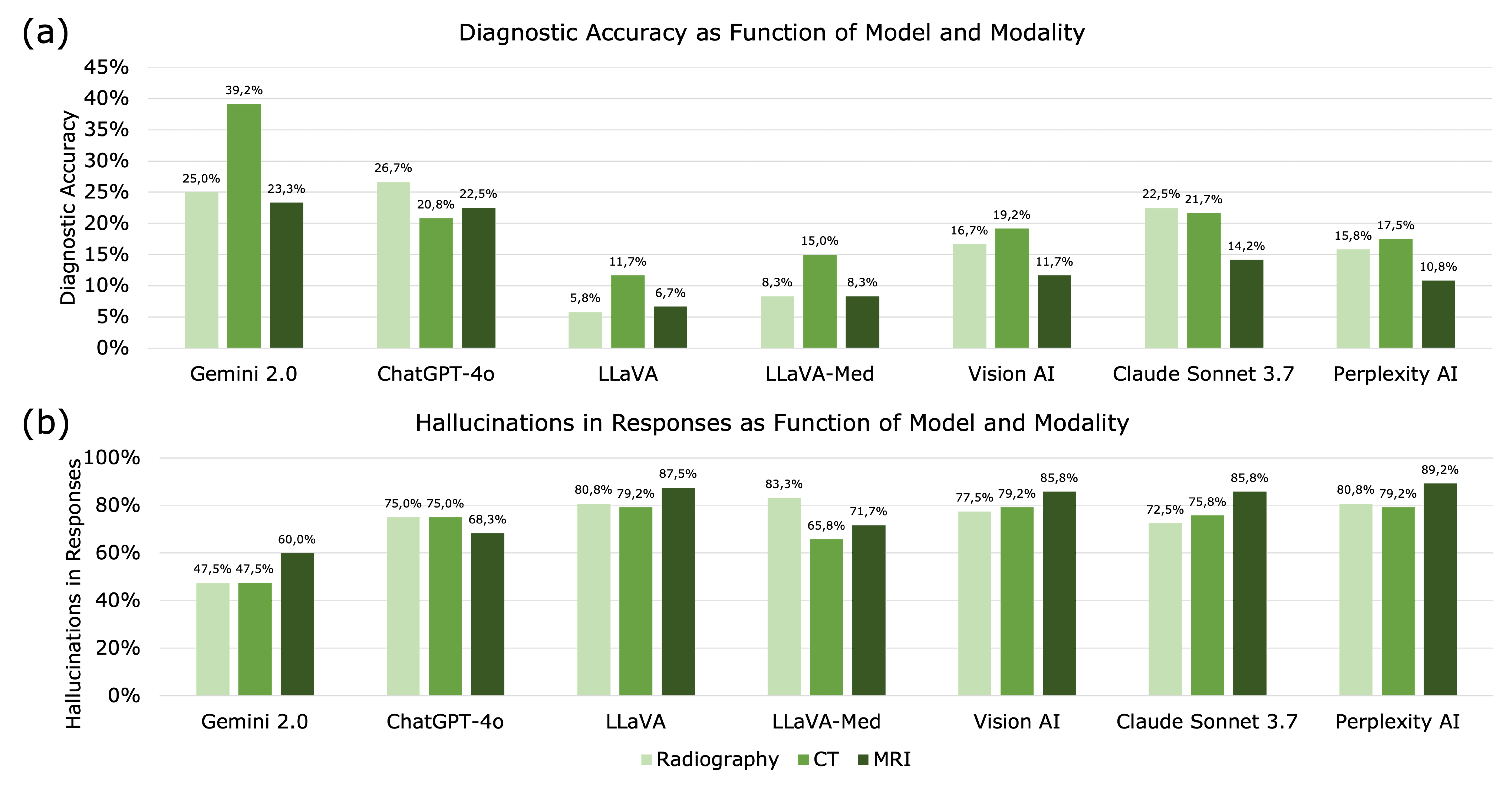

3.1. Diagnostic Accuracy

3.2. Imaging Modality

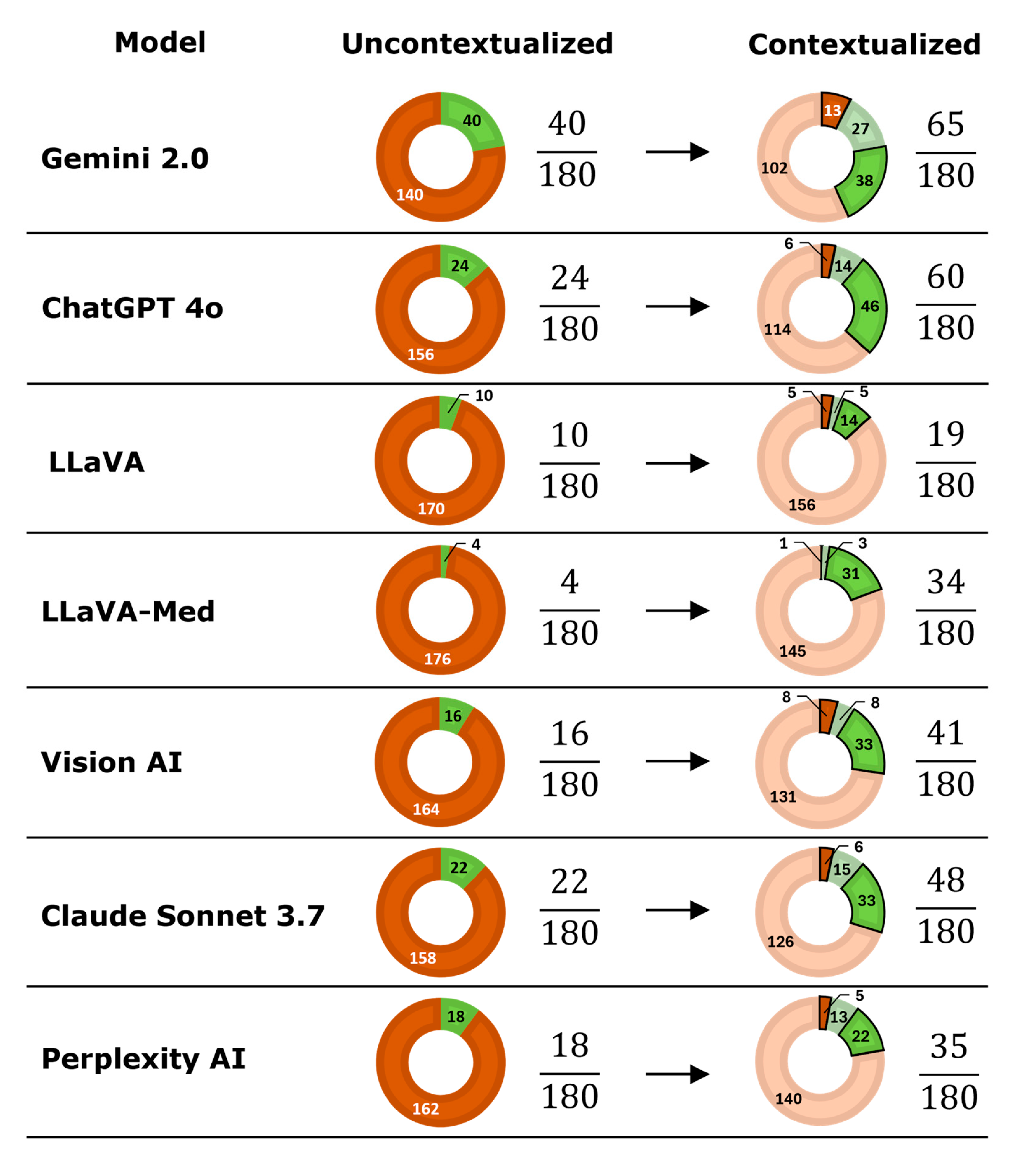

3.3. Contextualization

3.4. Hallucinations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VLLM | Visual large language model |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

References

- Nam, Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kyung, S.; Seo, J.; Song, J.M.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; Jo, W.; Park, H.; Sung, J.; et al. Multimodal Large Language Models in Medical Imaging: Current State and Future Directions. Korean J. Radiol. 2025, 26, 900–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.Y.; Chang, K.J.; Yang, C.F.; Wu, H.Y.; Chen, W.; Bansal, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.P.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, S.P.; et al. Towards a holistic framework for multimodal LLM in 3D brain CT radiology report generation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.Y.; Gou, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, T.; Chen, H.; Yang, D.; Ju, H.; Smith, K.E.; Sun, C.; Pan, J.; et al. From image to report: Automating lung cancer screening interpretation and reporting with vision-language models. J. Biomed. Inform. 2025, 171, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Mou, W.; Lai, Y.; Chen, J.; Lin, S.; Xu, L.; Lin, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, T.; Lin, A.; et al. Step into the era of large multimodal models: A pilot study on ChatGPT-4V(ision)’s ability to interpret radiological images. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, P.S.; Shim, W.H.; Suh, C.H.; Heo, H.; Park, K.J.; Kim, P.H.; Choi, S.J.; Ahn, Y.; Park, S.; Park, H.Y.; et al. Comparing Large Language Model and Human Reader Accuracy with New England Journal of Medicine Image Challenge Case Image Inputs. Radiology 2024, 313, e241668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, S.; George, D.D.; Singh, R.; Kohli, G.S.; Li, A.; Jalal, M.I.; Singh, A.; Furst, T.J.; Rahmani, R.; Vates, G.E.; et al. Accuracy and quality of ChatGPT-4o and Google Gemini performance on image-based neurosurgery board questions. Neurosurg. Rev. 2025, 48, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Kim, Y.; Wu, H. Hallucination benchmark in medical visual question answering. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.05827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Heybati, K.; Shammas-Toma, M. When vision meets reality: Exploring the clinical applicability of GPT-4 with vision. Clin. Imaging 2024, 108, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakır, K.; Işın, K.; Taş, A.; Önder, H. Diagnostic accuracy and consistency of ChatGPT-4o in radiology: Influence of image, clinical data, and answer options on performance. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy Achiron, R.; Kagasov, S.; Neeman, R.; Peri, T.; Fenton, C. Limited performance of ChatGPT-4v and ChatGPT-4o in image-based core radiology cases. Clin. Imaging 2026, 129, 110663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaura, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Masuda, T.; Nagayama, Y.; Uetani, H.; Kidoh, M.; Oda, S.; Funama, Y.; Hirai, T. Performance of State-of-the-Art Multimodal Large Language Models on an Image-Rich Radiology Board Examination: Comparison to Human Examinees. Acad. Radiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, F.; Han, T.; Makowski, M.R.; Truhn, D.; Bressem, K.K.; Adams, L. Integrating Text and Image Analysis: Exploring GPT-4V’s Capabilities in Advanced Radiological Applications Across Subspecialties. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e54948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.H.; Chen, K.; Anavim, S.; Phillipi, M.; Yeh, L.; Huynh, K.; Cortes, G.; Tran, J.; Tran, M.; Yaghmai, V.; et al. Large Language Models with Vision on Diagnostic Radiology Board Exam Style Questions. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 3096–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, M.S.; Siepmann, R.; Topp, D.; Nikoubashman, O.; Yüksel, C.; Kuhl, C.K.; Truhn, D.; Nebelung, S. Revolution or risk?-Assessing the potential and challenges of GPT-4V in radiologic image interpretation. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, B.C. Diagnostic Performance of Large Language Models in Multimodal Analysis of Radiolucent Jaw Lesions. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, Y.; Miki, S.; Yamagishi, Y.; Hanaoka, S.; Nakao, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Abe, O. Assessing accuracy and legitimacy of multimodal large language models on Japan Diagnostic Radiology Board Examination. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meddeb, A.; Rangus, I.; Pagano, P.; Dkhil, I.; Jelassi, S.; Bressem, K.; Scheel, M.; Wattjes, M.P.; Nagi, S.; Pierot, L.; et al. Evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of vision language models for neuroradiological image interpretation. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Schramm, S.; Adams, L.C.; Braren, R.; Bressem, K.K.; Keicher, M.; Platzek, P.S.; Paprottka, K.J.; Zimmer, C.; Hedderich, D.M.; et al. Benchmarking the diagnostic performance of open source LLMs in 1933 Eurorad case reports. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, D.; Sorin, V.; Barash, Y.; Konen, E.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Assessing GPT-4 multimodal performance in radiological image analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, N.; Gilbert, S.; Poisson, L.M.; Griffith, B.; Klochko, C. Performance of GPT-4 with Vision on Text- and Image-based ACR Diagnostic Radiology In-Training Examination Questions. Radiology 2024, 312, e240153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyeri, A.; Akbulut, R.; Gündoğdu, C.; Öztürk, T.; Ceylan, B.; Yalçın, N.F.; Dural, Ö.; Kasap, S.; Çildağ, M.B.; Ünsal, A.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of GPT-4o Compared to Radiology Residents in Emergency Abdominal Tomography Cases. Tomography 2025, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Yin, C.; Zhang, P. MedVH: Toward Systematic Evaluation of Hallucination for Large Vision Language Models in the Medical Context. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Radiography | CT | MRI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontextualized | Contextualized | Uncontextualized | Contextualized | Uncontextualized | Contextualized | |

| Gemini 2.0 | 9/60 (15.0%) | 21/60 (35.0%) | 20/60 (33.3%) | 27/60 (45.0%) | 11/60 (18.3%) | 17/60 (28.3%) |

| ChatGPT-4o | 12/60 (20.0%) | 20/60 (33.3%) | 6/60 (10.0%) | 18/60 (30.0%) | 6/60 (10.0%) | 21/60 (35.0%) |

| LLaVA | 3/60 (5.0%) | 4/60 (6.7%) | 4/60 (6.7%) | 10/60 (16.7%) | 3/60 (5.0%) | 5/60 (8.3%) |

| LLaVA-Med | 1/60 (1.7%) | 9/60 (15.0%) | 3/60 (5.0%) | 15/60 (25.0%) | 0/60 (0.0%) | 10/60 (16.7%) |

| Vision AI | 6/60 (10.0%) | 14/60 (23.3%) | 8/60 (13.3%) | 15/60 (25.0%) | 2/60 (3.3%) | 12/60 (20.0%) |

| Claude Sonnet 3.7 | 9/60 (15.0%) | 18/60 (30.0%) | 9/60 (15.0%) | 17/60 (28.3%) | 4/60 (6.7%) | 13/60 (21.7%) |

| Perplexity AI | 9/60 (15.0%) | 10/60 (16.7%) | 5/60 (8.3%) | 16/60 (26.7%) | 4/60 (6.7%) | 9/60 (15.0%) |

| Model | Plausible/180 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gemini 2.0 | 172/180 (95.6%) |

| ChatGPT-4o | 169/180 (93.9%) |

| Vision AI | 161/180 (89.4%) |

| Claude Sonnet 3.7 | 158/180 (87.8%) |

| Perplexity AI | 134/180 (74.4%) |

| LLaVA-Med | 118/180 (65.6%) |

| LLaVA | 91/180 (50.6%) |

| Model | Uncontextualized (n/180, %) | Contextualized (n/180, %) | Total (n/360, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 2.0 | 108/180 (60.0%) | 78/180 (43.3%) | 186/360 (51.7%) |

| ChatGPT-4o | 152/180 (84.4%) | 110/180 (61.1%) | 262/360 (72.8%) |

| LLaVA-Med | 148/180 (82.2%) | 117/180 (65.0%) | 265/360 (73.6%) |

| Vision AI | 156/180 (86.7%) | 129/180 (71.7%) | 285/360 (79.2%) |

| Claude Sonnet 3.7 | 151/180 (83.9%) | 131/180 (72.8%) | 282/360 (78.3%) |

| LLaVA | 155/180 (86.1%) | 142/180 (78.9%) | 297/360 (82.5%) |

| Perplexity AI | 156/180 (86.7%) | 142/180 (78.9%) | 298/360 (82.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

von der Stück, M.S.; Vuskov, R.; Westfechtel, S.; Siepmann, R.; Kuhl, C.; Truhn, D.; Nebelung, S. Visual Large Language Models in Radiology: A Systematic Multimodel Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Hallucinations. Life 2026, 16, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010066

von der Stück MS, Vuskov R, Westfechtel S, Siepmann R, Kuhl C, Truhn D, Nebelung S. Visual Large Language Models in Radiology: A Systematic Multimodel Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Hallucinations. Life. 2026; 16(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010066

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon der Stück, Marc Sebastian, Roman Vuskov, Simon Westfechtel, Robert Siepmann, Christiane Kuhl, Daniel Truhn, and Sven Nebelung. 2026. "Visual Large Language Models in Radiology: A Systematic Multimodel Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Hallucinations" Life 16, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010066

APA Stylevon der Stück, M. S., Vuskov, R., Westfechtel, S., Siepmann, R., Kuhl, C., Truhn, D., & Nebelung, S. (2026). Visual Large Language Models in Radiology: A Systematic Multimodel Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy and Hallucinations. Life, 16(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010066