Global Genomic Landscapes of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Universal GABA Biosynthetic Capacity with Strain-Level Functional Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome Dataset Collection

2.2. Genome Annotation

2.3. Identification of GABA-Related Genes

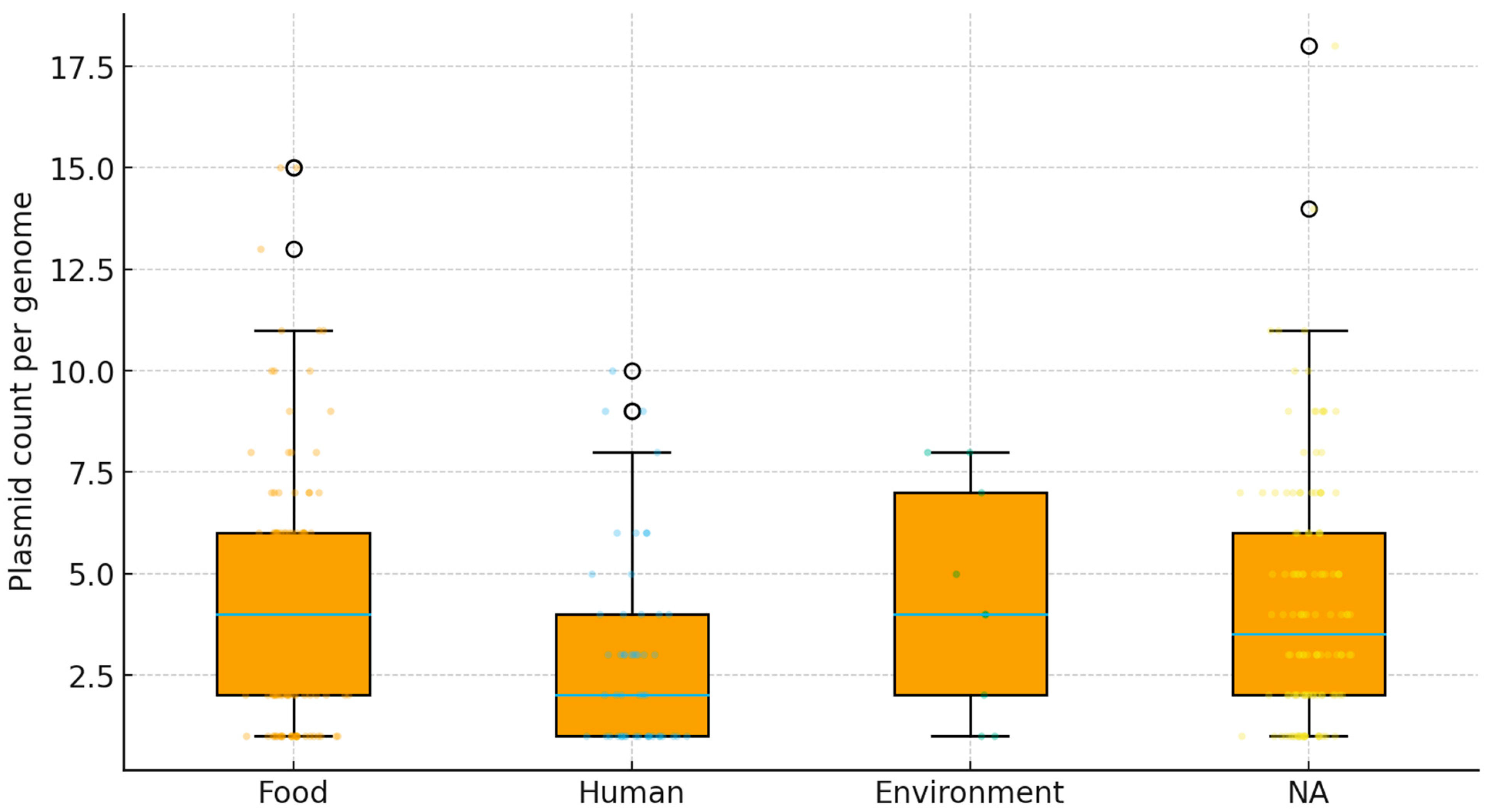

2.4. Plasmid Identification and Distribution

2.5. Probiotic Marker Gene Analysis

2.6. Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) Analysis

2.7. Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme (CAZyme) Annotation

2.8. Pangenome Analysis

2.9. Phylogenomic Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genome Characteristics of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum

3.2. Conservation of GABA-Related Genes and Reported Strain Production

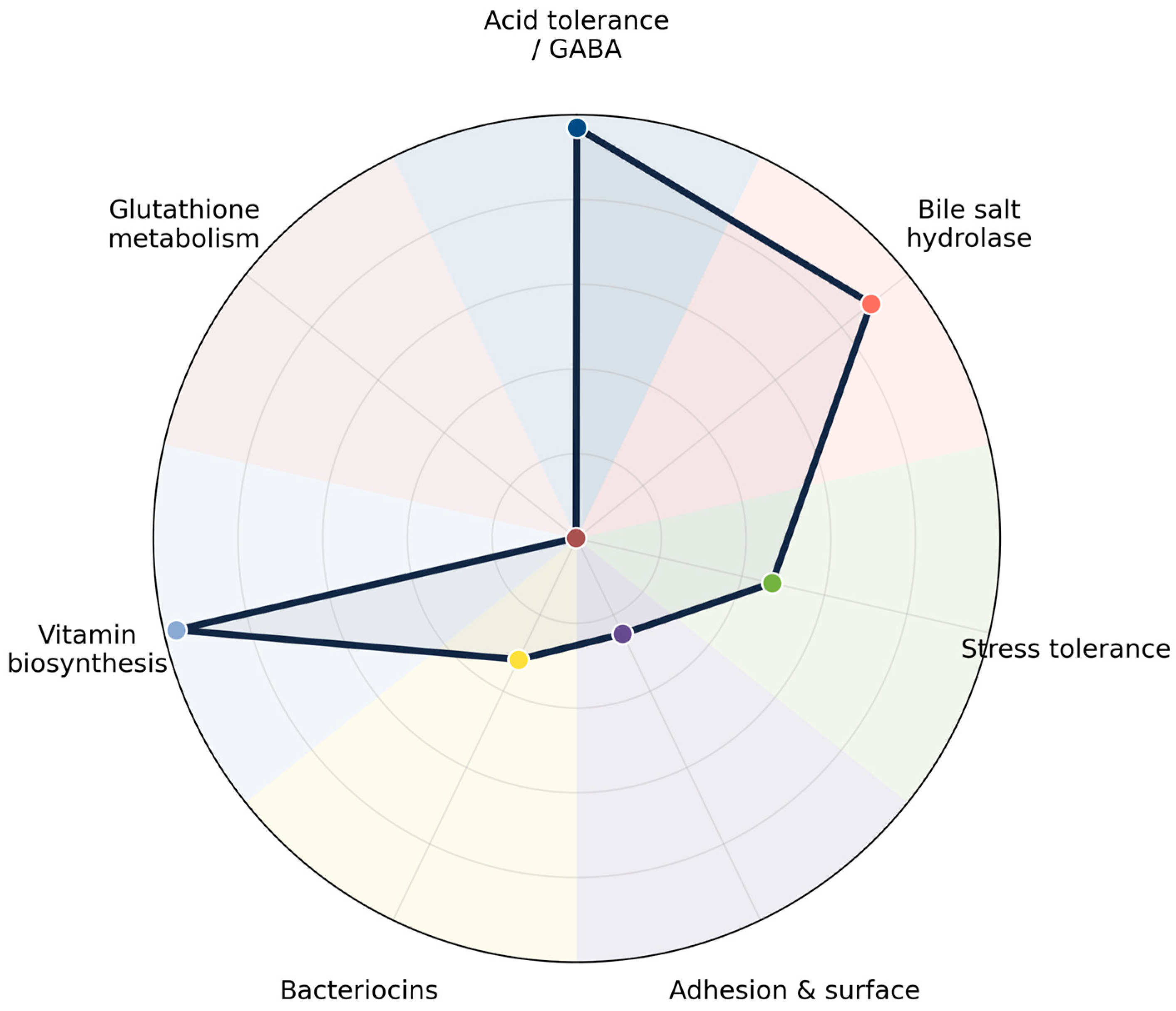

3.3. Probiotic Marker Genes

3.4. Secondary Metabolite and Functional Potential

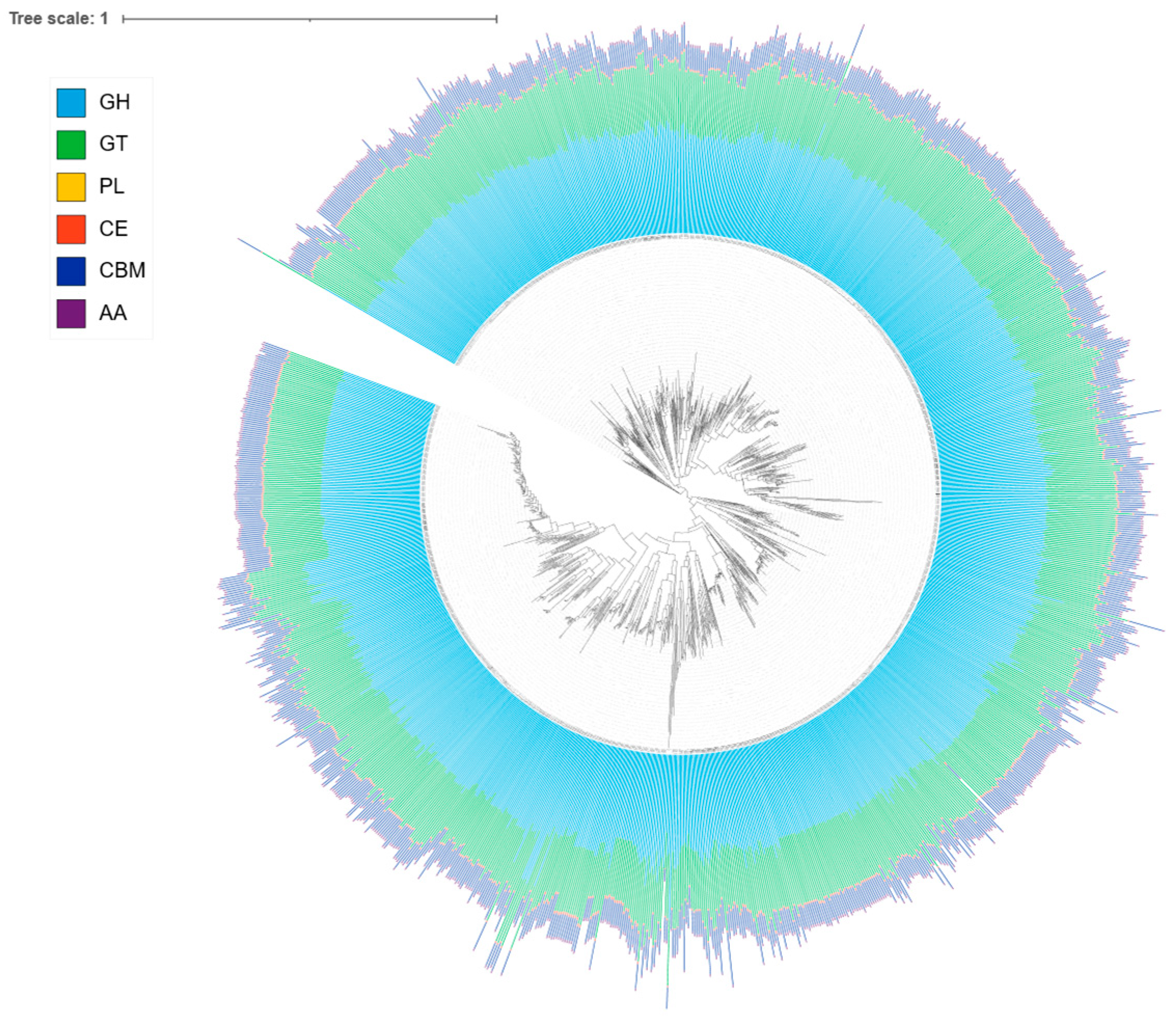

3.5. Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes) in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum

3.6. Pangenome Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhakal, R.; Bajpai, V.K.; Baek, K.H. Production of gaba (γ-Aminobutyric acid) by microorganisms: A review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, M.; Quílez, J.; Rafecas, M. Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a bioactive compound in foods: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Shirai, T.; Ochiai, H.; Kasao, M.; Hayakawa, K.; Kimura, M.; Sansawa, H. Blood-pressure-lowering effect of a novel fermented milk containing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in mild hypertensives. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X. Production of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid from Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siezen, R.J.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E. Genomic diversity and versatility of Lactobacillus plantarum, a natural metabolic engineer. Microb. Cell Factories 2011, 10, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A.; et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: Microbiota and beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, M.C.; Vaughan, E.E.; Kleerebezem, M.; de Vos, W.M. Lactobacillus plantarum—Survival, functional and potential probiotic properties in the human intestinal tract. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuengjayaem, S.; Booncharoen, A.; Tanasupawat, S. Characterization and comparative genomic analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing lactic acid bacteria from Thai fermented foods. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantachote, D.; Ratanaburee, A.; Hayisama-ae, W.; Sukhoom, A.; Nunkaew, T. The use of potential probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum DW12 for producing a novel functional beverage from mature coconut water. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 32, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, Y.; Fukao, M.; Fukaya, T. Genome Sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum KB1253, a Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Producer Used in GABA-Enriched Tomato Juice Production. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8, e00158-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Liu, W.; Han, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, P.; Meng, K. Optimization of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Production by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum FRT7 from Chinese Paocai. Foods 2023, 12, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Alagarsamy, K.; Suganthy, N.; Thangaleela, S.; Kesika, P.; Chaiyasut, C. The Role and Significance of Bacillus and Lactobacillus Species in Thai Fermented Foods. Fermentation 2022, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeswara, I.B.; Kittibunchakul, S.; Rahayu, E.S.; Domig, K.J.; Haltrich, D.; Nguyen, T.H. Microbial Production and Enzymatic Biosynthesis of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Using Lactobacillus plantarum FNCC 260 Isolated from Indonesian Fermented Foods. Processes 2021, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, S.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric acid by lactic acid bacteria isolated from a variety of Italian cheeses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7283–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C. Biosynthesis of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in Fermented Food Production. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 46, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C. Surviving the acid test: Responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surachat, K.; Deachamag, P.; Kantachote, D.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Jeenkeawpiam, K.; Chukamnerd, A. In silico comparative genomics analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DW12, a potential gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing strain. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 251, 126833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medini, D.; Donati, C.; Tettelin, H.; Masignani, V.; Rappuoli, R. The microbial pan-genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005, 15, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tettelin, H.; Riley, D.; Cattuto, C.; Medini, D. Comparative genomics: The bacterial pan-genome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintakovid, N.; Singkhamanan, K.; Yaikhan, T.; Nokchan, N.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Jitpakdee, J.; Kantachote, D.; Surachat, K. Probiogenomic analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SPS109: A potential GABA-producing and cholesterol-lowering probiotic strain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raethong, N.; Santivarangkna, C.; Visessanguan, W.; Santiyanont, P.; Mhuantong, W.; Chokesajjawatee, N. Whole-genome sequence analysis for evaluating the safety and probiotic potential of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus 9D3, a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing strain isolated from Thai pickled weed. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 969548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetiman, A.; Horzum, M.; Bahar, D.; Akbulut, M. Assessment of Genomic and Metabolic Characteristics of Cholesterol-Reducing and GABA Producer Limosilactobacillus fermentum AGA52 Isolated from Lactic Acid Fermented Shalgam Based on “In Silico” and “In Vitro” Approaches. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernandez-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramaki, T.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Endo, H.; Ohkubo, K.; Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Ge, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Yin, Y. dbCAN3: Automated carbohydrate-active enzyme and substrate annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115–W121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2--approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.E.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Caffrey, B.E.; Wels, M.; Joncour, P.; Hughes, S.; Gillet, B.; Kleerebezem, M.; van Hijum, S.A.; Leulier, F. Nomadic lifestyle of Lactobacillus plantarum revealed by comparative genomics of 54 strains isolated from different habitats. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4974–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M.; Hauser, L.; Jun, S.R.; Nookaew, I.; Leuze, M.R.; Ahn, T.H.; Karpinets, T.; Lund, O.; Kora, G.; Wassenaar, T.; et al. Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2015, 15, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleerebezem, M.; Boekhorst, J.; van Kranenburg, R.; Molenaar, D.; Kuipers, O.P.; Leer, R.; Tarchini, R.; Peters, S.A.; Sandbrink, H.M.; Fiers, M.W.E.J.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1990–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Tzeneva, V.A.; Castioni, A.; Wels, M.; Phan, H.T.; Rademaker, J.L.; Starrenburg, M.J.; Kleerebezem, M.; Molenaar, D.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E. Phenotypic and genomic diversity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from various environmental niches. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenaar, D.; Bringel, F.; Schuren, F.H.; de Vos, W.M.; Siezen, R.J.; Kleerebezem, M. Exploring Lactobacillus plantarum genome diversity by using microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 6119–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, J.R.; Wilkins, O.; Bywater-Ekegärd, M.; Smith, D.L. From yogurt to yield: Potential applications of lactic acid bacteria in plant production. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 111, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Hu, T.; Qu, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Z.; Dong, A. Plasmids from Food Lactic Acid Bacteria: Diversity, Similarity, and New Developments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 13172–13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, C.; Pei, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, Z.; Bai, H.; Ma, C.; Lan, M.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.; et al. Genomic and stress resistance characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum GX17, a potential probiotic for animal feed applications. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0124325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davray, D.; Deo, D.; Kulkarni, R. Plasmids encode niche-specific traits in Lactobacillaceae. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, T.; Huang, G.; Cao, Y. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912 using fed-batch fermentation. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.R.; Chang, J.Y.; Chang, H.C. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus buchneri isolated from kimchi and its neuroprotective effect on neuronal cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, R.; Choudhury, P.K. Lactic acid bacteria in fermented dairy foods: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production and its therapeutic implications. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Mazzacane, F.; Rizzello, C.G.; De Angelis, M.; Giuliani, G.; Meloni, M.; De Servi, B.; Gobbetti, M. Synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus plantarum DSM19463: Functional grape must beverage and dermatological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratanaburee, A.; Kantachote, D.; Charernjiratrakul, W.; Sukhoom, A. Selection of γ-aminobutyric acid-producing lactic acid bacteria and their potential as probiotics for use as starter cultures in Thai fermented sausages (Nham). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Man, C.X.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.W.; Jiang, Y.J. Evaluation of improved γ-aminobutyric acid production in yogurt using Lactobacillus plantarum NDC75017. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanamool, V.; Hongsachart, P.; Soemphol, W. Screening and characterisation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from Thai fermented fish (Plaa-som) in Nong Khai and its application in Thai fermented vegetables (Som-pak). Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-Y.; Garcia, C.V.; Song, Y.-C.; Lee, S.-P. GABA-enriched water dropwort produced by co-fermentation with Leuconostoc mesenteroides SM and Lactobacillus plantarum K154. LWT 2016, 73, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, H.J.; Shin, M.; Yang, S.-Y.; Yang, J.; Jung, Y.H. Enhanced production of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) using Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014 with simple medium composition. LWT 2021, 137, 110443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Ra, C.H. Evaluation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by Lactobacillus plantarum using two-step fermentation. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, F.S.; Chay, S.Y.; Zarei, M.; Meor Hussin, A.S.; Ibadullah, W.Z.; Zaharuddin, N.D.; Wazir, H.; Saari, N. Potentiality of Self-Cloned Lactobacillus plantarum Taj-Apis362 for Enhancing GABA Production in Yogurt under Glucose Induction: Optimization and Its Cardiovascular Effect on Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats. Foods 2020, 9, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, L.; Tang, J.; Xiang, W. Characterization of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-producing Saccharomyces cerevisiae and coculture with Lactobacillus plantarum for mulberry beverage brewing. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareian, M.; Oskoueian, E.; Forghani, B.; Ebrahimi, M. Production of a wheat-based fermented rice enriched with γ-amino butyric acid using Lactobacillus plantarum MNZ and its antihypertensive effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitpakdee, J.; Kantachote, D.; Kanzaki, H.; Nitoda, T. Selected probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods for functional milk production: Lower cholesterol with more beneficial compounds. LWT 2021, 135, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Tun, H.M.; Law, Y.S.; Khafipour, E.; Shah, N.P. Common Distribution of gad Operon in Lactobacillus brevis and its GadA Contributes to Efficient GABA Synthesis toward Cytosolic Near-Neutral pH. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsuzaki, N.; Shima, J.; Kawamoto, S.; Momose, H.; Kimura, T. Production of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus paracasei isolated from traditional fermented foods. Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Y. Lactic acid bacterial cell factories for gamma-aminobutyric acid. Amino Acids 2010, 39, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Shah, N.P. Restoration of GABA production machinery in Lactobacillus brevis by accessible carbohydrates, anaerobiosis and early acidification. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G. Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Martoni, C.J.; Parent, M.; Prakash, S. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of a microencapsulated bile salt hydrolase-active Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30242 yoghurt formulation in hypercholesterolaemic adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Environmental stress responses in Lactobacillus: A review. Proteomics 2004, 4, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Alegría, Á.; Bron, P.A.; de Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lemos, J.A.; Linares, D.M.; Ross, P.; Stanton, C.; et al. Stress Physiology of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 837–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, M.; O’Flaherty, S.; Claesson, M.J.; Turroni, F.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; van Sinderen, D.; O’Toole, P.W. Genome-scale analyses of health-promoting bacteria: Probiogenomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Nieuwboer, M.; van Hemert, S.; Claassen, E.; de Vos, W.M. Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 and its host interaction: A dozen years after the genome. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorov, S.D. Bacteriocins from Lactobacillus plantarum—Production, genetic organization and mode of action: Produção, organização genética e modo de ação. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pang, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qin, G.; Tan, Z. Bacteriocin-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains with Antimicrobial Activity Screened from Bamei Pig Feces. Foods 2022, 11, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaysi, N.; Hadian Seyed Mahaleh, S.A.H.; Zadeh Hosseingholi, E.; Nami, Y.; Panahi, B. Machine learning based association analysis of plantaricin gene occurrence and diversity with antimicrobial potential in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strains isolated from Iranian traditional dairy products. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Amaretti, A.; Raimondi, S. Folate production by probiotic bacteria. Nutrients 2011, 3, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelta, J.L.; Buey, R.M.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Vandamme, E.J. Microbial biotechnology for the synthesis of (pro)vitamins, biopigments and antioxidants: Challenges and opportunities. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, F.S.; Duong, M.N. Manganese acquisition by Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 158, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wei, B.; Wen, Y.; Xu, X.; Rao, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, Y.; et al. Revealing the potent probiotic properties and alcohol degradation capabilities of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BGI-J9 by combining complete genomic and phenotypic analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1664033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Mai, H.; Su, J.; Ma, X.; Zhong, J. The First Lanthipeptide from Lactobacillus iners, Inecin L, Exerts High Antimicrobial Activity against Human Vaginal Pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0212322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Shukla, B.N.; Singh, V.; Sharma, Y.; Choudhary, P.; Rao, A. GLYCOCINS: The sugar peppered antimicrobials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 75, 108415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöner, T.A.; Gassel, S.; Osawa, A.; Tobias, N.J.; Okuno, Y.; Sakakibara, Y.; Shindo, K.; Sandmann, G.; Bode, H.B. Aryl Polyenes, a Highly Abundant Class of Bacterial Natural Products, Are Functionally Related to Antioxidative Carotenoids. Chembiochem 2016, 17, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Joishy, T.K.; Khan, M.R. Exploration of the genomic potential of the probiotic bacterium Lactiplantibacillus plantarum JBC5 (LPJBC5). Discov. Bact. 2025, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huidrom, S.; Ngashangva, N.; Khumlianlal, J.; Sharma, K.C.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Devi, S.I. Genomic insights from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BRD3A isolated from Atingba, a traditional fermented rice-based beverage and analysis of its potential for probiotic and antimicrobial activity against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1357818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Jiang, T.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Dong, B.; Wu, Q.; Gu, B. Carbohydrate-active enzyme profiles of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain 84-3 contribute to flavor formation in fermented dairy and vegetable products. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenea, G.N.; Ascanta, P. Bioprospecting of Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides Through Genome Characterization of a Novel Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum UTNGt21A Strain: A Promising Natural Antimicrobials Factory. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 868025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C.; Crawford, T.W., Jr.; Iorizzo, M. Enzymatic activities of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Technological and functional role in food processing and human nutrition. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenea, G.N.; Hidalgo, J.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Cifuentes, V. Genomic and functional insights into Lactiplantibacillus plantarum UTNGt3 from Ecuadorian Amazon Chrysophyllum oliviforme: A safe and promising probiotic. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1634475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iarusso, I.; Mahony, J.; Pannella, G.; Lombardi, S.J.; Gagliardi, R.; Coppola, F.; Pellegrini, M.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P. Diversity of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in Wild Fermented Food Niches. Foods 2025, 14, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidan, H.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Simat, V.; Trif, M.; Tabanelli, G.; Kostka, T.; Montanari, C.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Özogul, F. Recent developments of lactic acid bacteria and their metabolites on foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria: Facts and gaps. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Function | Number of Strains | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gadA | Glutamate decarboxylase (GAD); catalyzes conversion of glutamate to GABA | 0 | 0.00 |

| gadB | Glutamate decarboxylase (GAD); catalyzes conversion of glutamate to GABA | 1240 | 100.00 |

| gadC | Glutamate/GABA antiporter; exports GABA in exchange for glutamate | 1240 | 100.0 |

| gabT | GABA aminotransferase; catabolizes GABA to succinate semialdehyde | 0 | 0.00 |

| gabD | Succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase; converts SSA to succinate | 3 | 0.24 |

| gabP | GABA permease; imports GABA | 0 | 0.00 |

| gltP | Glutamate transporter (alternative system; not detected) | 0 | 0.00 |

| gltT | Glutamate transporter; supports glutamate uptake for GABA biosynthesis | 1237 | 99.80 |

| Species | gadA | gadB | gadC | gabT | gabD | gabP | gltP | gltT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. brevis | 99.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 99.5 |

| L. buchneri | 57.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 98.1 | 98.1 |

| L. casei | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| L. fermentum | 40.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 99.1 |

| L. helveticus | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| L. paracasei | 0.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Strain | Isolation Source | Reported GABA Production (g/L) | Genome Available | Year | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNCC 260 | Indonesian fermented foods | 0.809 | Yes | 2021 | Indonesia | [14] |

| FRT7 | Chinese Paocai | 1.159 | No | 2023 | China | [12] |

| LSI2-1 | Thai fermented vegetables | 22.94 | Yes | 2021 | Thailand | [9] |

| DW12 | Thai fermented beverage (red seaweed) | Not specified | Yes | 2021 | Thailand | [47] |

| KB1253 | Japanese pickle | Not specified | Yes | 2019 | Japan | [11] |

| NDC75017 | Traditional fermented dairy products | 3.15 | No | 2015 | China | [48] |

| L10-11 | Thai fermented fish (Plaa-som) | 15.74 | No | 2021 | Thailand | [49] |

| K154 | Kimchi | 15.53 | No | 2013 | South Korea | [50] |

| EJ2014 | Rice bran | 19.80 | No | 2013 | South Korea | [51] |

| C48 | Cheese | 0.016 | No | 2007 | Italy | [15] |

| KCTC 3103 | Unknown | 0.67 | No | – | – | [52] |

| Taj-Apis362 | Honeycomb and honeybee stomach | 0.737 | No | 2015 | Malaysia | [53] |

| BC114 | Sichuan Paocai (fermented vegetable) | 3.45 | No | – | China | [54] |

| MNZ | Fermented soybean | 0.408 | No | – | – | [55] |

| K255 | Kimchi | 0.821 | No | – | South Korea | PubMed |

| SPS109 | Thai fermented food | 1.157 | Yes | 2024 | Thailand | [56] |

| Category | Gene | Function/Role | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid tolerance/GABA | gadB | Glutamate decarboxylase A—converts glutamate to GABA (acid tolerance, neurotransmitter production) | 100.0 |

| gltT | Glutamate transporter—glutamate uptake | 99.8 | |

| gadC | Glutamate/GABA antiporter—exports GABA, imports glutamate | 100.0 | |

| gabD | Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase—GABA catabolism | 0.2 | |

| gabT | GABA transaminase—GABA shunt metabolism | 0.0 | |

| gltP | Proton/glutamate symporter—glutamate uptake | 0.0 | |

| Bile salt hydrolase | bsh | Bile salt hydrolase—detoxifies bile salts, enhances gut survival | 88.9 |

| Stress tolerance | dnaK | Heat shock protein Hsp70—stress response, protein folding | 37.7 |

| groEL | Chaperonin—protein folding under stress | 56.9 | |

| Adhesion and surface | slpA | Surface layer protein—adhesion to host cells | 25.0 |

| Bacteriocins | plnE | Plantaricin E—antimicrobial peptide | 47.7 |

| plnF | Plantaricin F—antimicrobial peptide | 46.5 | |

| pediocin | Pediocin-like bacteriocin—antimicrobial against pathogens | 1.0 | |

| Vitamin biosynthesis | folA | Dihydrofolate reductase—folate biosynthesis | 100.0 |

| folB | Dihydroneopterin aldolase—folate biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| folC | Folate synthase—folate biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| ribA | GTP cyclohydrolase II—riboflavin biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| ribB | 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase—riboflavin biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| ribC | Riboflavin synthase subunit—riboflavin biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| ribD | Diaminohydroxyphosphoribosylaminopyrimidine deaminase—riboflavin biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| ribE | Lumazine synthase—riboflavin biosynthesis | 100.0 | |

| Glutathione metabolism | gshA | Glutamate–cysteine ligase—glutathione biosynthesis | 0.2 |

| gshB | Glutathione synthetase—glutathione biosynthesis | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wonglapsuwan, M.; Ninrat, T.; Chaichana, N.; Dechathai, T.; Suwannasin, S.; Singkhamanan, K.; Pomwised, R.; Surachat, K. Global Genomic Landscapes of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Universal GABA Biosynthetic Capacity with Strain-Level Functional Diversity. Life 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010047

Wonglapsuwan M, Ninrat T, Chaichana N, Dechathai T, Suwannasin S, Singkhamanan K, Pomwised R, Surachat K. Global Genomic Landscapes of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Universal GABA Biosynthetic Capacity with Strain-Level Functional Diversity. Life. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleWonglapsuwan, Monwadee, Thitima Ninrat, Nattarika Chaichana, Thitaporn Dechathai, Sirikan Suwannasin, Kamonnut Singkhamanan, Rattanaruji Pomwised, and Komwit Surachat. 2026. "Global Genomic Landscapes of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Universal GABA Biosynthetic Capacity with Strain-Level Functional Diversity" Life 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010047

APA StyleWonglapsuwan, M., Ninrat, T., Chaichana, N., Dechathai, T., Suwannasin, S., Singkhamanan, K., Pomwised, R., & Surachat, K. (2026). Global Genomic Landscapes of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Universal GABA Biosynthetic Capacity with Strain-Level Functional Diversity. Life, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010047