Effect of Different Light Quality and Photoperiod on Mycelium and Fruiting Body Growth of Tricholoma giganteum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Fungal Strains

2.1.2. Cultivation Medium

2.1.3. Light Treatment Set Up

2.2. Measurement of Growth Parameters

2.3. Biochemical Analyses

2.3.1. Antioxidant and Enzyme Activity Assays

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO)

DPPH

2.3.2. Nutrient Component Analysis

Polysaccharide

Protein

Glutamate

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Agronomic Traits Analysis

3.1.1. Effects of Different Light Qualities on Mycelial Growth of T. giganteum

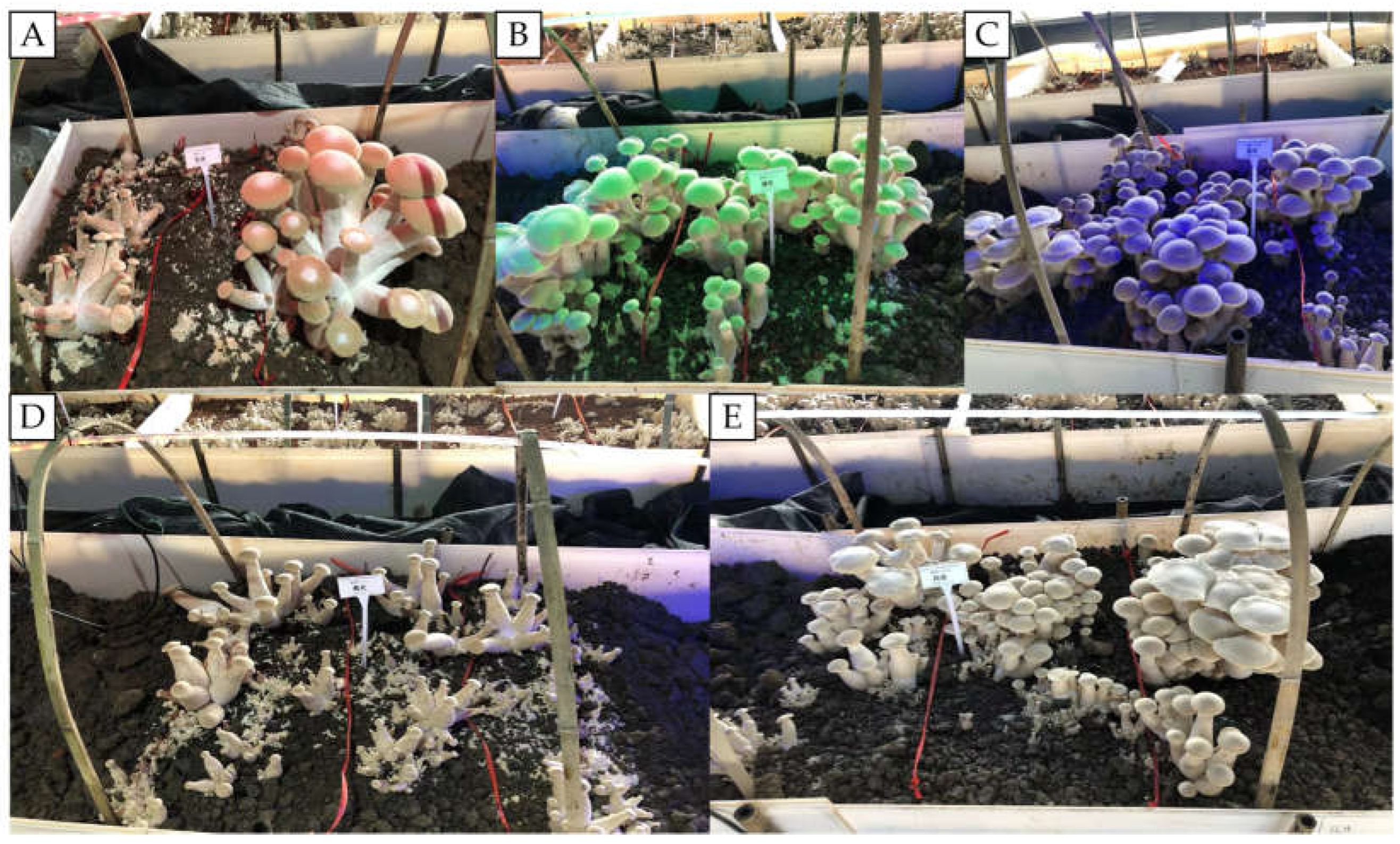

3.1.2. Effects of Different Light Qualities on the Growth and Development of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

3.1.3. Effects of Different Durations of GL Exposure on the Growth and Development of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

3.2. Physiological Enzyme Activity and Antioxidant Analysis

3.2.1. Effects of Different Light Qualities on the Physiological Enzyme Activities and Antioxidant of T. giganteum Mycelium

3.2.2. Effects of Different Light Qualities on the Physiological Enzyme Activities and Antioxidant of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

3.2.3. Effects of Different Durations of GL Exposure on the Physiological Enzyme Activities and Antioxidants of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

3.3. Nutrient Content Analysis

3.3.1. Effects of Different Light Qualities on Nutrient Content of T. giganteum Mycelium

3.3.2. Effects of Different Light Qualities on the Nutrient Content of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

3.3.3. Effects of Different Durations of GL Exposure on Nutrient Content of T. giganteum Fruiting Bodies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, Q.; Zhan, M.; Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, A. Identification, nutritional value and functional component analysis of A wild giant mushroom plant. Mol. Plant Breed. 2021, 19, 7282–7289. [Google Scholar]

- Bellettini, M.B.; Fiorda, F.A.; Maieves, H.A.; Teixeira, G.L.; Ávila, S.; Hornung, P.S.; Júnior, A.M.; Ribani, R.H. Factors Affecting Mushroom Pleurotus spp. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; He, H.; Song, W. Application of Light-Emitting Diodes and the Effect of Light Quality on Horticultural Crops: A Review. HortScience 2019, 54, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.S.; Chung, I.M.; Hwang, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Yu, C.Y.; Ghimire, B.K.; Jung, W.S.; Chung, I.M.; Hwang, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Application of Light-Emitting Diodes for Improving the Nutritional Quality and Bioactive Compound Levels of Some Crops and Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2021, 26, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Ju, Y.C.; Kim, S.M.; Koo, H.M. Effect of Color of Light Emitting Diode on Development of Fruit Body in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Mycobiology 2013, 41, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glukhova, L.B.; Sokolyanskaya, L.O.; Plotnikov, E.V.; Gerasimchuk, A.L.; Karnachuk, O.V.; Solioz, M.; Karnachuk, R.A. Increased Mycelial Biomass Production by Lentinula edodes Intermittently Illuminated by Green Light Emitting Diodes. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiniola, R.C.; Pambid, R.C.; Bautista, A.S.; Dulay, R.M.R. Light-Emitting Diode Enhances the Biomass Yield and Antioxidant Activity of Philippine Wild Mushroom Lentinus swartzii. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2021, 2, 202008435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.F.; Yusoff, H.; Koay, M.H.; Budin, S.; Sh Abdul Nasir, S.M.F. Effects of Various LED Light Colours on Yield and Physical Characteristics of White Oyster Mushrooms. ESTEEM Acad. J. 2023, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.F.; Yusoff, H.; Nasir, S.M.F.S.A. Enhancing White Oyster Mushroom Cultivation through Light Stimulation Using White Led. J. Mek. 2023, 46, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Liang, C.H.; Liang, Z.C. Effect of LED Light on the Production of Fruiting Bodies and Nucleoside Compounds of Cordyceps militaris at Different Growth Stages of Solid-State Fermentation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 153, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, H.; Sun, Y.; Xia, R.; Hou, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, S.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.; et al. Effect of Light on Quality of Preharvest and Postharvest Edible Mushrooms and Its Action Mechanism: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Study on the Effects of Different Light Supply Modes on the Development and Extracellular Enzyme Activity of Ganoderma lucidum. Agriculture 2024, 14, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, C.; Li, D. Effect of different LED light qualities on growth and development of Tremella fuciformis. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2015, 36, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kho, C.H.; Kan, S.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Cheng, H.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Chiou, P.C.; Shieh, C.J.; Liu, Y.C. Analysis of Exopolysaccharide Production Patterns of Cordyceps militaris under Various Light-Emitting Diodes. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 112, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, A.; Janczewska, A.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Dziedziński, M.; Siwulski, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. The Effect of Light Conditions on the Content of Selected Active Ingredients in Anatomical Parts of the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus L.). PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavya, M.L.; Shewale, S.R.; Rajoriya, D.; Hebbar, H.U. Impact of Blue LED Illumination and Natural Photosensitizer on Bacterial Pathogens, Enzyme Activity and Quality Attributes of Fresh-Cut Pineapple Slices. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, M.; Villani, A.; Paciolla, F.; Mulè, G.; Paciolla, C.; Loi, M.; Villani, A.; Paciolla, F.; Mulè, G.; Paciolla, C. Challenges and Opportunities of Light-Emitting Diode (LED) as Key to Modulate Antioxidant Compounds in Plants. A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, M.; Atila, F.; Sen, F.; Yemen, S. The Effect of Different LED Wavelengths Used in the Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus on Quality Parameters of the Mushroom during the Storage Process. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Mao, L.Y. Effects of Blue and Green Light-Emitting Diode (LED) on the Vegetative and Reproductive Growth of Black Jelly Mushroom (Auricularia Auricula-Judae). Adv. Sustain. Technol. (ASET) 2024, 3, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Hu, H.Y.; Ma, Y.S.; Qin, J.W.; Li, C.T.; Li, Y. Effects of Light Quality on Agronomic Traits, Antioxidant Capacity and Nutritional Composition of Sarcomyxa edulis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.S.; Min, C.W.; Woo, J.H.; Choi, B.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Lee, K.-W.; Rahman, M.A.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Light Quality Plays a Crucial Role in Regulating Germination, Photosynthetic Efficiency, Plant Development, Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, and Nutrient Acquisition in Alfalfa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapaev, J.; Sapaev, B.; Erkinov, Z.; Baymuratova, G.; Eshbabaev, T. Growing of Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushrooms under the Artificial Light and Its Influence on D-Vitamin Content. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 883, 012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykchaylova, O.; Dubova, H.; Lomberg, M.; Negriyko, A.; Poyedinok, N. Influence of Low-Intensity Light on the Biosynthetic Activity of the Edible Medicinal Mushroom Hericium erinaceus (Bull.: Fr.) Pers. in Vitro. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2023, 75, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Lee, T.M.; Chung, C.P.; Tsai, Y.C.; Huang, D.W.; Huang, P.H. Growth of Cordyceps militaris Cultivation and Its Bioactive Component Accumulation as Affected by Various Single-Wavelength Light-Emitting Diodes (LED) Light Sources. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xue, X.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Effects of LEDs Light Spectra on the Growth, Yield, and Quality of Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Cultured in Plant Factory. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2530–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, C.; da Silva, A.J.R.; Lopes, M.L.M.; Fialho, E.; Valente-Mesquita, V.L. Polyphenol Oxidase Activity, Phenolic Acid Composition and Browning in Cashew Apple (Anacardium occidentale, L.) after Processing. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyida, V.T.; Hayati, S.N.; Wiyono, T.; Darsih, C.; Ratih, D. Effect of Aqueous Extraction Method on Total Water-Soluble Polysaccharides Content and Phytochemical Properties of White Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1377, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Gao, J.; Li, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhao, F.; Gao, J.; Li, H.; Huang, S.; et al. Identification of Peptides from Edible Pleurotus eryngii Mushroom Feet and the Effect of Delaying D-Galactose-Induced Senescence of PC12 Cells through TLR4/NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Pathways. Foods 2024, 13, 3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gao, C.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Song, W.; Wei, W.; Liu, L. Fine-Tuning Pyridoxal 5′-Phosphate Synthesis in Escherichia coli for Cadaverine Production in Minimal Culture Media. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynaloo, E.; Yang, Y.-P.; Dikici, E.; Landgraf, R.; Bachas, L.G.; Daunert, S. Design of a Mediator-Free, Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Biosensor for Glutamate Detection. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2021, 31, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doneva, D.; Pál, M.; Szalai, G.; Vasileva, I.; Brankova, L.; Misheva, S.; Janda, T.; Peeva, V. Manipulating the Light Spectrum to Increase the Biomass Production, Physiological Plasticity and Nutritional Quality of Eruca sativa L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 217, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Jing, Z.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Y.; Cai, J.; Wang, B.; Xie, B.; et al. Blue Light and Its Receptor White Collar Complex (FfWCC) Regulates Mycelial Growth and Fruiting Body Development in Flammulina filiformis. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 309, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, Y.; Xia, R.; Qiao, Y.; Ren, H.; Lyu, Y.; Pan, S.; Xin, G. Blue Light Attenuated the Umami Loss of Postharvest Lentinula edodes during Spore Discharge: Crucial Roles of Energy Status. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, S.; Xiang, T.; Kitazawa, H.; Sun, H.; Guo, Y. Effects of Light Irradiation on the Textural Properties and Energy Metabolism of Postharvest Shiitake Mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e16066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Luo, K.; Wang, B.; Huang, B.; Fei, P.; Zhang, G. Inhibition of Polyphenol Oxidase for Preventing Browning in Edible Mushrooms: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 6796–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Wei, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W. The Effects of Different Light Qualities on the Growth and Nutritional Components of Pleurotus citrinopileatus. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1554575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Light Quality | Illumination Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 d | 5 d | 10 d | ||||

| Mycelial Traits | Growth Speed (mm·d−1) | Mycelial Traits | Growth Speed (mm·d−1) | Mycelial Traits | Growth Speed (mm·d−1) | |

| UV | ++ | 0.32 ± 0.02 b | + | 0.21 ± 0.06 c | + | 0.18 ± 0.07 c |

| GL | ++++ | 0.62 ± 0.06 ab | +++ | 0.46 ± 0.09 b | +++ | 0.44 ± 0.07 b |

| BL | ++++ | 0.74 ± 0.05 a | ++++ | 0.74 ± 0.07 a | ++++ | 0.58 ± 0.09 a |

| WL | +++ | 0.56 ± 0.02 ab | +++ | 0.40 ± 0.09 b | ++++ | 0.42 ± 0.06 b |

| RL | +++ | 0.52 ± 0.08 ab | ++++ | 0.42 ± 0.05 b | +++ | 0.35 ± 0.09 b |

| CK | +++ | 0.59 ± 0.05 ab | ++++ | 0.51 ± 0.05 a | +++ | 0.55 ± 0.11 b |

| Light Quality | Incubation Time (d) | Primordium Formation Time (d) | First Harvesting Time (d) | First Level (kg) | Yield (kg) | Average Yield (kg) | Bioconversion Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL | 40 | 18 | 39 | 3.75 ± 0.13 a | 3.86 ± 0.09 a | 0.32 ± 0.05 a | 66.4 |

| BL | 41 | 19 | 41 | 3.09 ± 0.21 b | 4.02 ± 0.22 a | 0.34 ± 0.01 a | 67.0 |

| RL | 45 | 25 | 48 | 2.04 ± 0.11 b | 3.47 ± 0.07 b | 0.29 ± 0.02 b | 57.8 |

| YL | 46 | 24 | 47 | 1.31 ± 0.07 c | 2.12 ± 0.1 c | 0.18 ± 0.08 b | 35.4 |

| CK | 45 | 24 | 47 | 2.71 ± 0.16 b | 3.86 ± 0.18 b | 0.33 ± 0.03 a | 64.2 |

| Light Quality | Mean Total Length (mm) | Pileus | Diameter of Stipe (mm) | Average Single Weight (g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Mean Thickness (mm) | Mean Diameter (cm) | Upper | Lower | |||

| GL | 16.34 ± 0.97 b | Milky white | 23.47 ± 0.28 ab | 14.64 ± 1.33 a | 23.89 ± 2.35 a | 44.84 ± 4.32 b | 105.92 ± 1.55 a |

| BL | 12.11 ± 1.31 c | Milky white | 25.47 ± 0.54 a | 12.57 ± 1.85 ab | 24.47 ± 1.39 a | 45.68 ± 2.72 a | 99.32 ± 2.81 ab |

| RL | 19.69 ± 1.46 a | Light yellow | 25.12 ± 0.78 a | 10.22 ± 1.08 b | 27.03 ± 3.64 a | 48.68 ± 1.84 a | 103.56 ± 11.20 a |

| YL | 16.21 ± 2.37 b | Deep yellow | 19.43 ± 0.75 b | 5.71 ± 0.54 c | 24.87 ± 3.49 a | 47.29 ± 5.05 a | 69.12 ± 7.13 c |

| CK | 11.62 ± 0.85 c | Deep yellow | 23.85 ± 0.72 ab | 9.52 ± 0.81 b | 23.98 ± 1.97 a | 45.85 ± 4.87 a | 91.29 ± 11.33 b |

| Time (h) | Incubation Time (d) | Primordium Formation Time (d) | First Harvesting Time (d) | First Level (kg) | Yield (kg) | Average Yield (kg) | Bioconversion Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 40 | 18 | 39 | 4.07 ± 0.18 ab | 4.97 ± 0.31 a | 0.41 ± 0.05 a | 82.6 |

| 4 | 36 | 18 | 37 | 5.35 ± 0.24 a | 5.91 ± 0.21 a | 0.49 ± 0.01 a | 98.4 |

| 8 | 40 | 18 | 39 | 3.57 ± 0.23 b | 4.94 ± 0.09 a | 0.41 ± 0.05 a | 82.2 |

| 12 | 40 | 18 | 39 | 4.09 ± 0.11 ab | 4.85 ± 0.42 a | 0.40 ± 0.01 a | 80.8 |

| 24 | 40 | 18 | 39 | 3.99 ± 0.24 ab | 4.65 ± 0.18 b | 0.39 ± 0.09 b | 77.4 |

| CK | 45 | 24 | 47 | 3.84 ± 0.36 ab | 4.84 ± 0.48 a | 0.40 ± 0.02 a | 80.4 |

| Time (h) | Mean Total Length (cm) | Pileus | Diameter of Stipe/(mm) | Average Single Weight/(g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Mean Thickness (mm) | Mean Diameter (cm) | Upper | Lower | |||

| 2 | 22.70 ± 0.53 ab | Milky white | 23.76 ± 1.57 ab | 11.48 ± 1.53 b | 26.43 ± 1.20 a | 39.88 ± 0.80 a | 95.73 ± 1.59 b |

| 4 | 24.61 ± 0.43 a | Milky white | 25.01 ± 1.78 a | 12.98 ± 1.17 a | 29.54 ± 3.75 a | 41.39 ± 2.26 a | 102.40 ± 5.28 a |

| 8 | 19.20 ± 0.82 bc | Light yellow | 24.01 ± 0.61 ab | 12.25 ± 1.16 ab | 20.95 ± 1.39 b | 28.61 ± 1.85 b | 96.28 ± 5.06 ab |

| 12 | 19.32 ± 0.33 bc | Deep yellow | 22.16 ± 2.16 c | 11.90 ± 1.89 b | 20.03 ± 1.03 b | 26.86 ± 1.86 bc | 94.99 ± 5.18 b |

| 24 | 12.09 ± 0.09 d | Deep yellow | 21.55 ± 1.55 c | 11.32 ± 1.32 b | 22.00 ± 1.01 b | 28.20 ± 1.80 b | 91.16 ± 4.10 b |

| CK | 17.82 ± 0.92 c | Deep yellow | 23.02 ± 0.76 bc | 12.08 ± 0.73 ab | 20.85 ± 2.52 b | 29.81 ± 6.58 b | 91.70 ± 4.51 b |

| Light Quality | Illumination Time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 d | 5 d | 10 d | |||||||

| SOD (U·mL−1) | DPPH (%) | PPO (U·mL−1) | SOD (U·mL−1) | DPPH (%) | PPO (U·mL−1) | SOD (U·mL−1) | DPPH (%) | PPO (U·mL−1) | |

| UV | 164.23 ± 0.68 b | 141.32 ± 0.35 b | 164.23 ± 6.8 b | 141.32 ± 5.35 b | 135.54 ± 8.14 a | 118.29 ± 5.68 b | 121.36 ± 5.89 b | 82.71 ± 1.12 b | 133.36 ± 6.11 b |

| GL | 188.51 ± 0.12 a | 199.15 ± 0.43 b | 188.51 ± 9.2 a | 199.15 ± 9.43 b | 122.08 ± 12.82 ab | 161.94 ± 5.45 b | 189.25 ± 5.49 b | 93.21 ± 2.12 b | 146.51 ± 6.46 a |

| BL | 183.41 ± 0.89 a | 204.51 ± 0.11 ab | 183.41 ± 8.9 a | 204.51 ± 9.11 ab | 122.88 ± 14.12 ab | 127.32 ± 5.89 b | 194.56 ± 6.12 ab | 76.16 ± 1.22 b | 153.76 ± 5.12 a |

| WL | 187.19 ± 0.46 a | 212.24 ± 0.62 ab | 187.19 ± 4.6 a | 212.24 ± 9.62 ab | 118.79 ± 12.82 b | 154.09 ± 5.12 b | 202.74 ± 10.68 ab | 83.75 ± 3.42 b | 148.96 ± 5.89 a |

| RL | 184.95 ± 0.89 a | 276.11 ± 0.13 a | 184.95 ± 8.9 a | 276.11 ± 10.13 a | 123.55 ± 11.26 ab | 240.20 ± 10.49 a | 261.14 ± 10.89 a | 121.82 ± 5.11 a | 144.21 ± 6.89 a |

| CK | 186.72 ± 0.49 a | 231.23 ± 0.42 ab | 186.72 ± 4.9 a | 231.23 ± 10.42 ab | 118.51 ± 10.95 b | 130.95 ± 5.89 b | 213.57 ± 10.46 ab | 89.21 ± 2.26 b | 153.20 ± 4.49 a |

| Light Quality | Enzyme Activity and Antioxidant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SOD (U·mL−1) | DPPH (%) | PPO (U·mL−1) | |

| GL | 120.78 ± 5.58 b | 148.01 ± 6.11 a | 125.19 ± 5.46 a |

| BL | 186.06 ± 6.03 a | 132.13 ± 5.03 b | 112.81 ± 4.20 c |

| RL | 142.83 ± 5.19 ab | 76.13 ± 1.07 b | 114.87 ± 4.36 b |

| YL | 166.96 ± 5.63 ab | 53.09 ± 1.01 c | 136.39 ± 5.10 a |

| CK | 121.74 ± 2.98 b | 106.08 ± 4.14 b | 113.36 ± 5.23 bc |

| Time (h) | Enzyme Activity and Antioxidant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SOD (U·mL−1) | DPPH (%) | PPO (U·mL−1) | |

| 2 | 133.33 ± 6.19 ab | 78.11 ± 1.05 b | 113.61 ± 2.11 c |

| 4 | 168.76 ± 5.63 ab | 133.11 ± 5.04 ab | 116.67 ± 2.46 c |

| 8 | 176.06 ± 6.03 a | 133.12 ± 5.02 ab | 134.31 ± 2.01 a |

| 12 | 138.83 ± 4.19 ab | 133.11 ± 5.01 ab | 126.17 ± 2.35 b |

| 24 | 119.58 ± 5.56 b | 139.01 ± 4.21 a | 127.18 ± 2.37 b |

| 0 | 118.64 ± 2.68 b | 109.08 ± 4.22 b | 115.46 ± 2.22 c |

| Light Quality | Illumination Time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 d | 5 d | 10 d | |||||||

| Nutrient Content (g·100 g−1) | Nutrient Content (g·100 g−1) | Nutrient Content (g·100 g−1) | |||||||

| Protein | Polysaccharide | Glutamate | Protein | Polysaccharide | Glutamate | Protein | Polysaccharide | Glutamate | |

| UV | 0.33 ± 0.01 e | 0.39 ± 0.01 b | 0.90 ± 0.04 c | 0.58 ± 0.02 d | 0.52 ± 0.02 d | 0.94 ± 0.02 e | 0.52 ± 0.02 c | 3.15 ± 0.11 c | 0.92 ± 0.04 b |

| GL | 0.66 ± 0.05 cd | 0.54 ± 0.05 a | 1.47 ± 0.06 ab | 0.65 ± 0.04 cd | 0.59 ± 0.04 d | 1.31 ± 0.03 a | 1.75 ± 0.09 b | 5.45 ± 0.12 ab | 1.11 ± 0.09 a |

| BL | 0.51 ± 0.02 de | 0.61 ± 0.02 a | 1.63 ± 0.07 a | 0.85 ± 0.02 ab | 0.84 ± 0.02 ab | 1.16 ± 0.06 c | 1.62 ± 0.06 b | 6.45 ± 0.11 a | 0.92 ± 0.07 b |

| WL | 0.95 ± 0.06 b | 0.50 ± 0.02 a | 1.67 ± 0.05 a | 0.98 ± 0.09 ab | 0.76 ± 0.06 bc | 1.23 ± 0.03 b | 2.19 ± 0.09 b | 5.03 ± 0.19 abc | 0.94 ± 0.02 b |

| RL | 0.80 ± 0.05 bc | 0.45 ± 0.01 b | 1.36 ± 0.03 b | 0.74 ± 0.05 bc | 0.87 ± 0.05 ab | 1.11 ± 0.02 d | 0.62 ± 0.02 c | 4.02 ± 0.14 bc | 0.93 ± 0.02 b |

| CK | 1.61 ± 0.06 a | 0.57 ± 0.01 a | 1.32 ± 0.03 b | 1.73 ± 0.06 a | 0.71 ± 0.04 bcd | 1.11 ± 0.05 d | 3.55 ± 0.11 a | 5.73 ± 0.16 ab | 0.94 ± 0.04 b |

| Light Quality | Nutrient Content (g·100 g−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Polysaccharide | Glutamate | |

| GL | 33.42 ± 0.94 b | 31.01 ± 0.82 a | 4.39 ± 0.14 a |

| BL | 30.54 ± 0.91 c | 18.51 ± 0.83 abc | 3.50 ± 0.13 b |

| RL | 35.33 ± 0.87 a | 20.49 ± 0.66 ab | 3.15 ± 0.17 c |

| YL | 35.92 ± 0.89 a | 20.42 ± 0.64 abc | 3.19 ± 0.12 bc |

| CK | 33.64 ± 0.85 b | 20.31 ± 0.57 abc | 4.15 ± 0.116 a |

| Time (h) | Nutrient Content (g·100 g−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Polysaccharide | Glutamate | |

| 2 | 33.88 ± 0.84 ab | 36.51 ± 0.81 ab | 3.35 ± 0.12 d |

| 4 | 35.80 ± 0.91 a | 38.17 ± 0.93 a | 5.70 ± 0.13 a |

| 8 | 34.33 ± 0.83 ab | 35.17 ± 0.89 ab | 5.75 ± 0.13 a |

| 12 | 34.15 ± 0.94 ab | 33.02 ± 0.84 ab | 4.66 ± 0.14 c |

| 24 | 33.48 ± 0.83 b | 30.87 ± 0.81 b | 4.50 ± 0.13 c |

| CK | 34.46 ± 0.91 a | 30.86 ± 0.81 b | 4.48 ± 0.13 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luo, Q.; Zhan, M.; Yan, S.; Xie, T.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Lin, J. Effect of Different Light Quality and Photoperiod on Mycelium and Fruiting Body Growth of Tricholoma giganteum. Life 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010039

Luo Q, Zhan M, Yan S, Xie T, Huang X, Wang R, Lu H, Wang S, Lin J. Effect of Different Light Quality and Photoperiod on Mycelium and Fruiting Body Growth of Tricholoma giganteum. Life. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Qingqing, Meirong Zhan, Shengze Yan, Ting Xie, Xianxin Huang, Ruijuan Wang, Huan Lu, Shengyou Wang, and Juanjuan Lin. 2026. "Effect of Different Light Quality and Photoperiod on Mycelium and Fruiting Body Growth of Tricholoma giganteum" Life 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010039

APA StyleLuo, Q., Zhan, M., Yan, S., Xie, T., Huang, X., Wang, R., Lu, H., Wang, S., & Lin, J. (2026). Effect of Different Light Quality and Photoperiod on Mycelium and Fruiting Body Growth of Tricholoma giganteum. Life, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010039