Advanced AI-Powered System for Comprehensive Thyroid Cancer Detection and Malignancy Risk Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Context

1.2. Literature Review

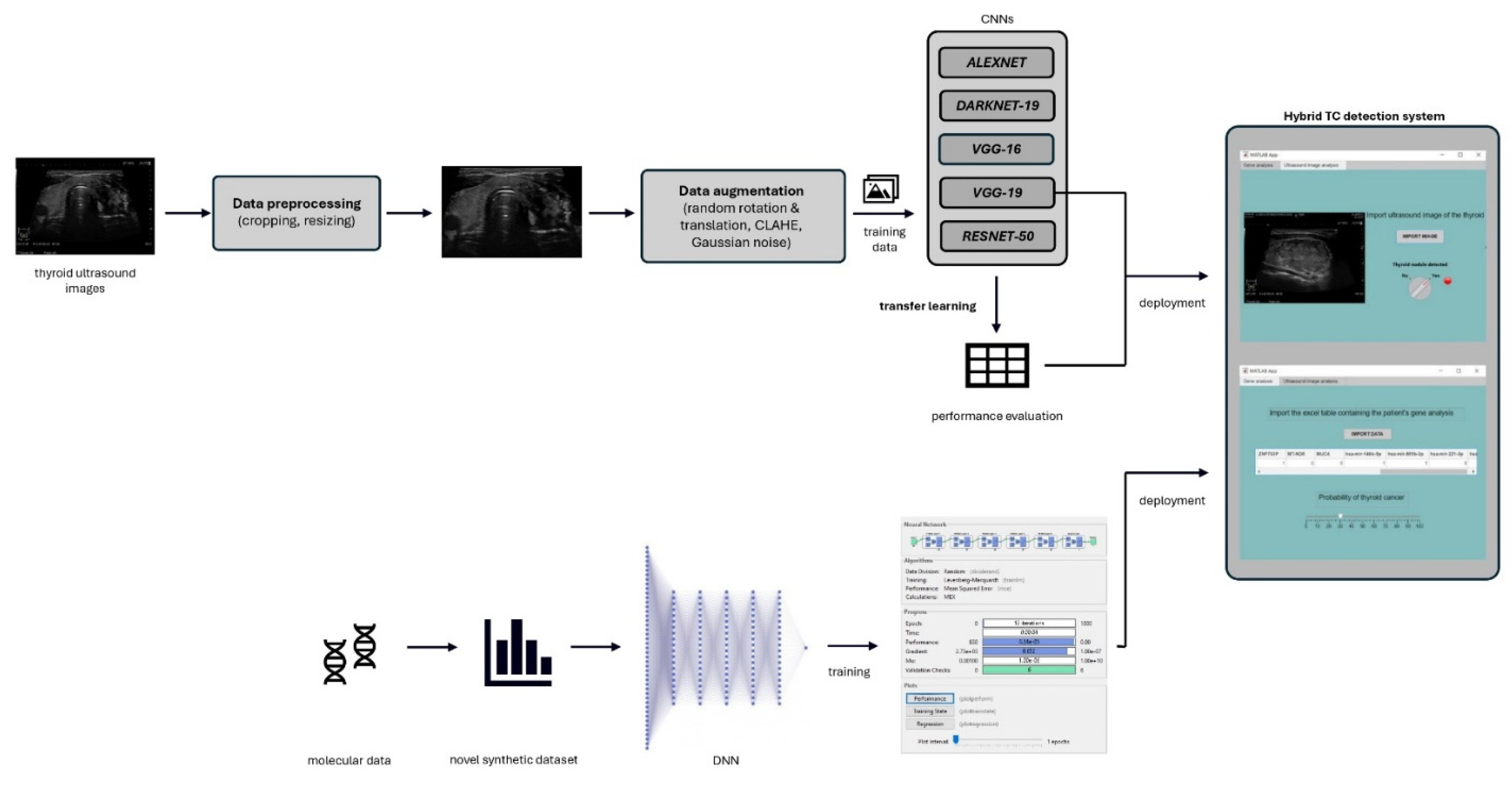

2. Materials and Methods

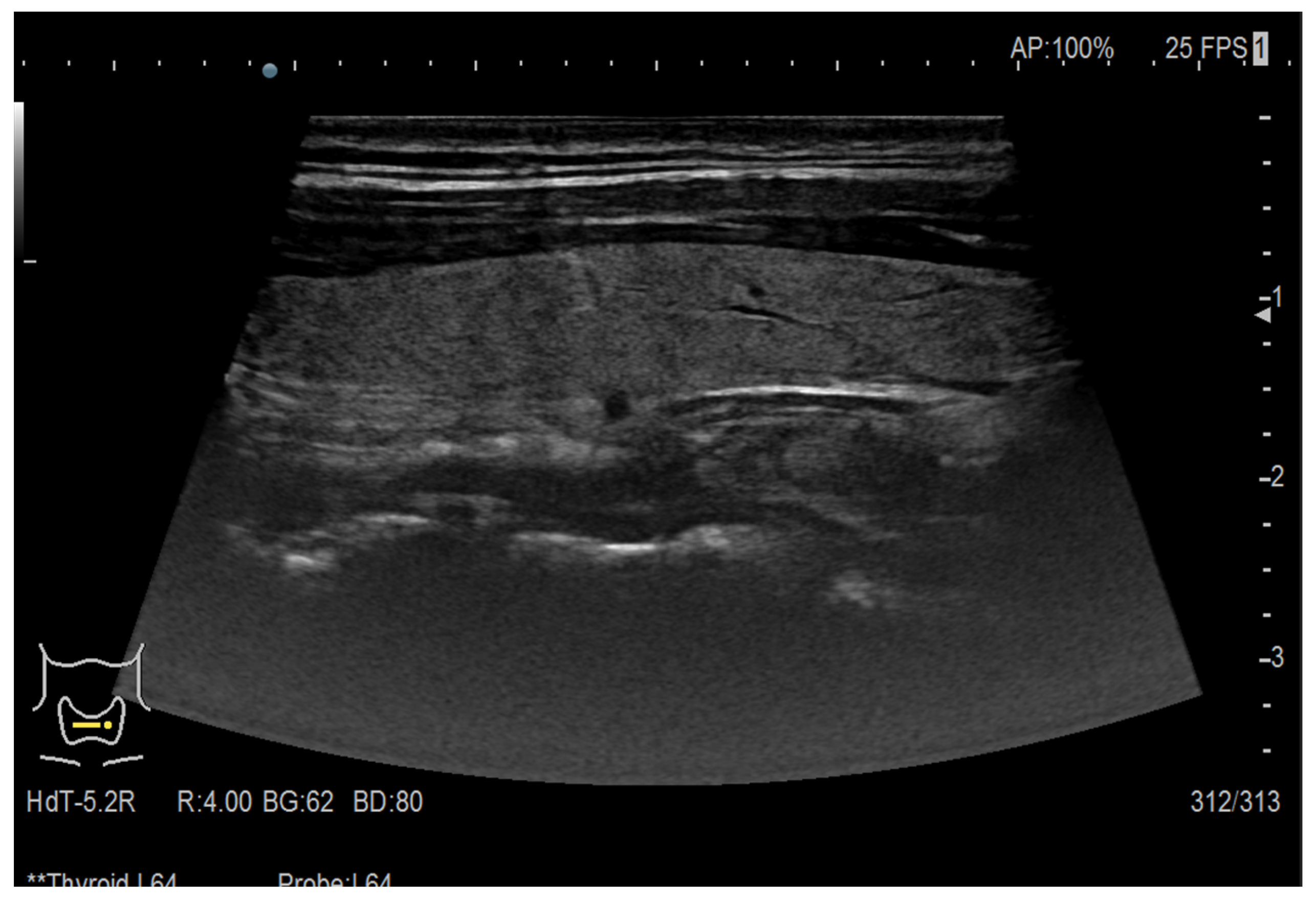

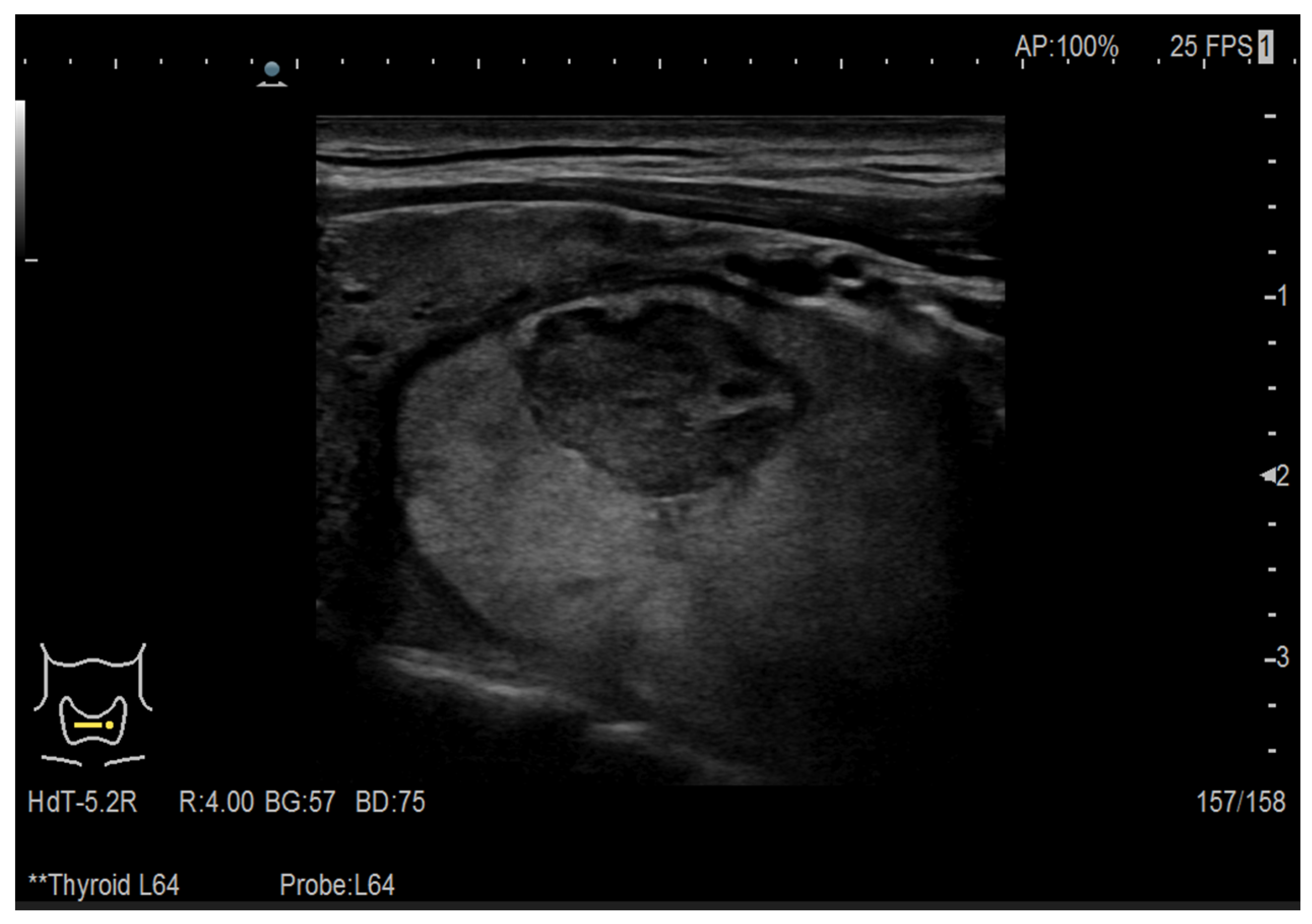

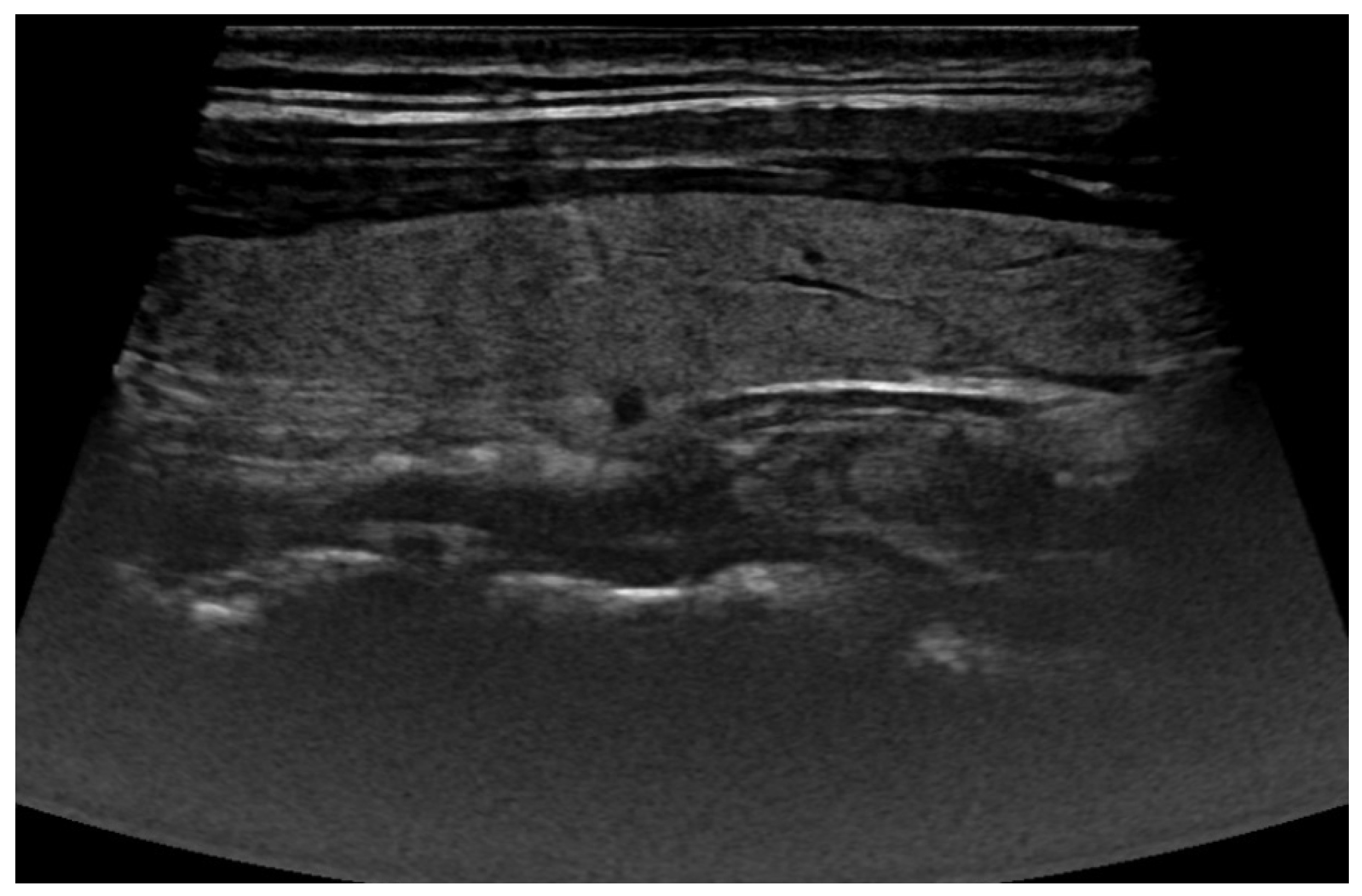

2.1. Ultrasound Images

2.1.1. The Data

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

2.1.3. Data Augmentation

2.1.4. Model Architecture

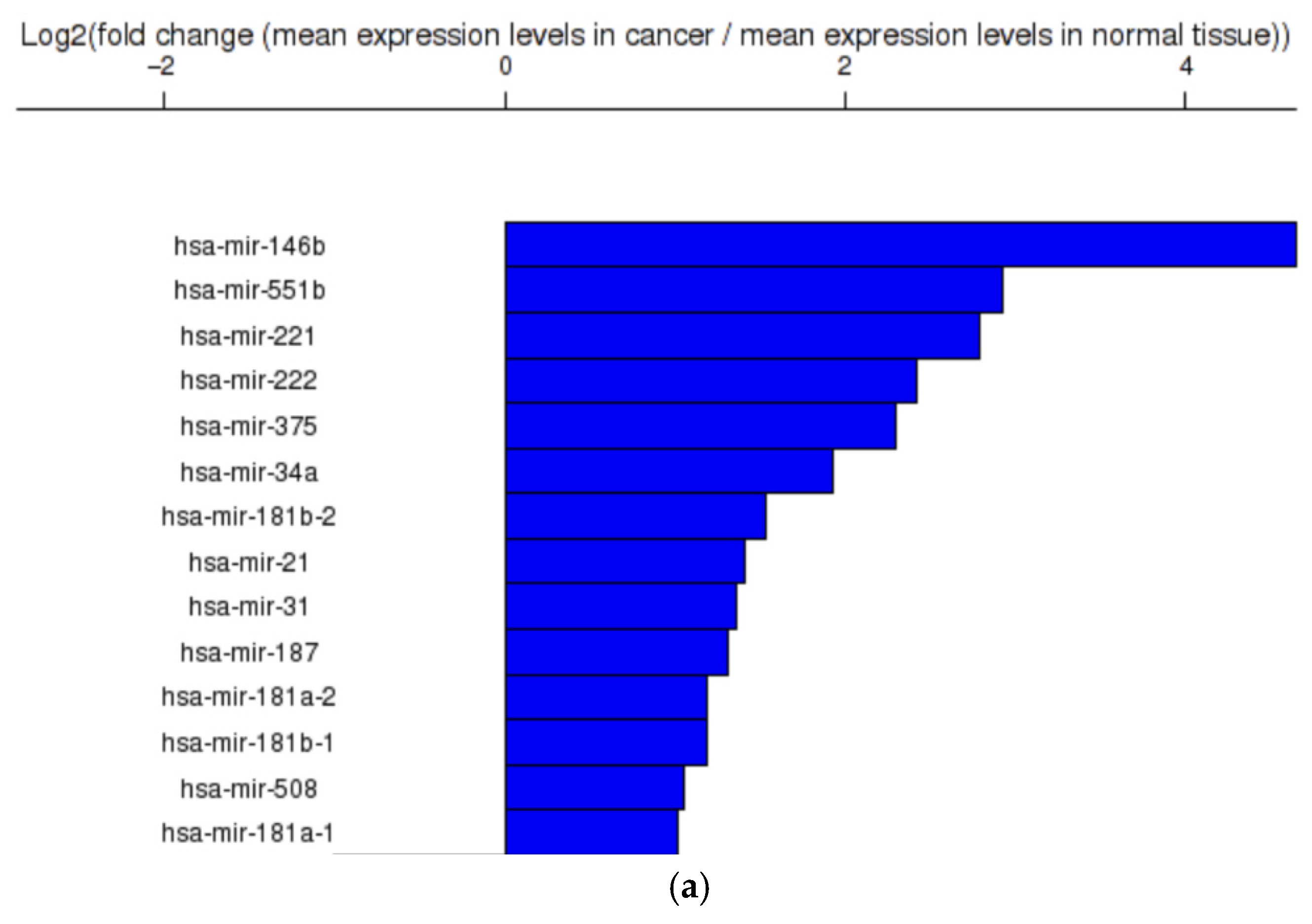

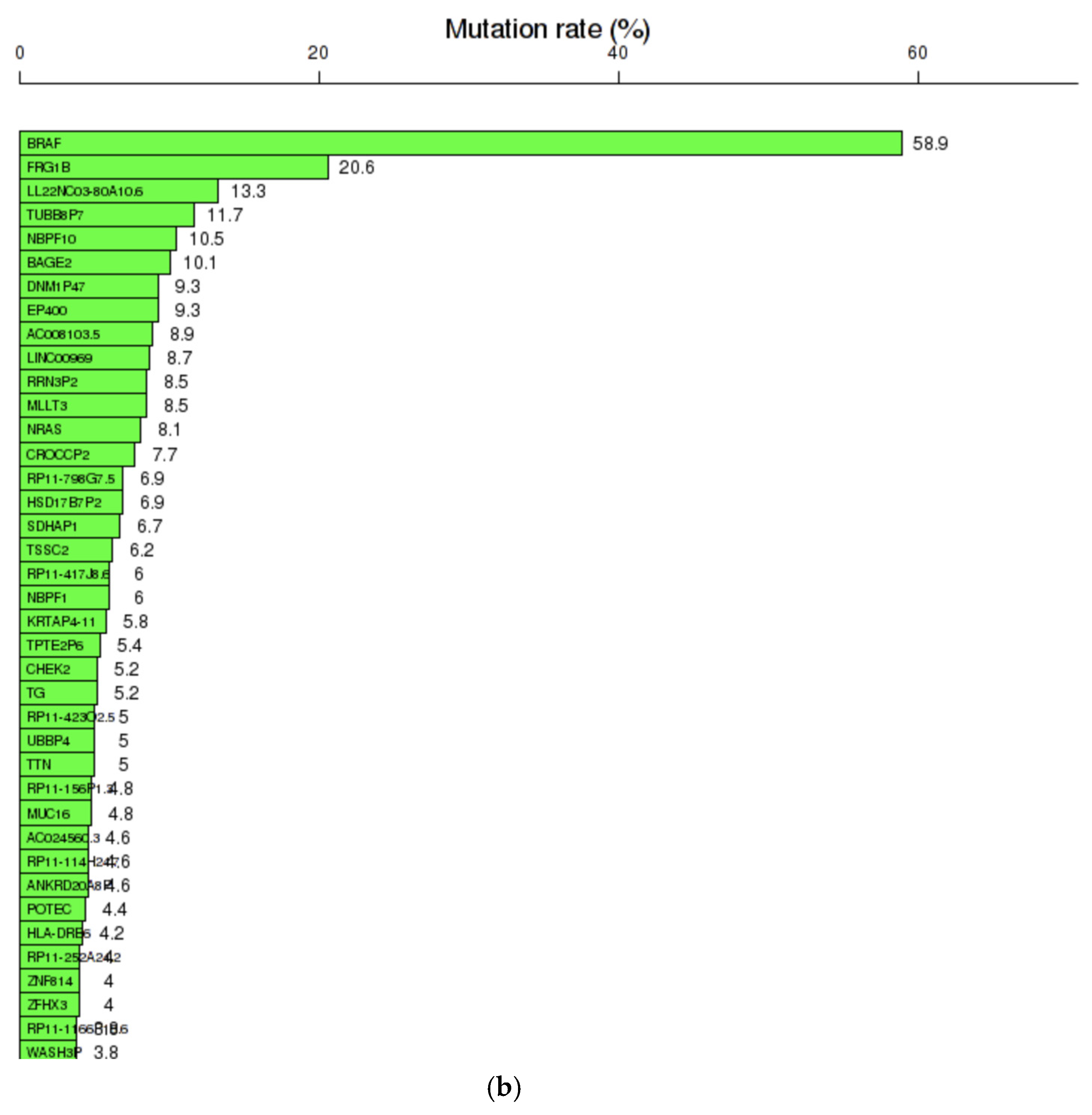

2.2. Gene Analysis

2.2.1. Dataset Construction

2.2.2. Model Architecture

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Thyroid Nodule Diagnosis Based on Ultrasound Images: Binary Classification Problem Solved Using Convolutional Neural Networks

3.2. Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis Based on Genes and Gene Mutations: Regression Problem Solved with Deep Neural Network

3.3. Integration of the Two Diagnosis Models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, N.; Ren, J. Ultrasound-base radiomics for discerning lymph node metastasis in thyroid cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Radiol. 2024, 31, 3118–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegriti, G.; Frasca, F.; Regalbuto, C.; Squatrito, S.; Vigneri, R. Worldwide increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: Update on epidemiology and risk factors. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 2013, 965212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gosnell, J.E.; Roman, S.A. Geographic influences in the global rise of thyroid cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H.A.; Zulfanahri; Frannita, E.L.; Ardiyanto, I.; Choridah, L. Computer aided diagnosis for thyroid cancer system based on internal and external characteristics. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 33, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enas, Y. Oncogenesis of thyroid cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 1191. [Google Scholar]

- Silaghi, C.A.; Lozovanu, V.; Georgescu, C.E.; Georgescu, R.D.; Susman, S.; Năsui, B.A.; Dobrean, A.; Silaghi, H. Thyroseq v3, Afirma GSC, and microRNA panels versus previous molecular tests in the preoperative diagnosis of indeterminate thyroid nodules: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 649522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rago, T.; Vitti, P. Risk stratification of thyroid nodules: From ultrasound features to TIRADS. Cancers 2022, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lin, M.; Wu, S. Validating and comparing C-TIRADS, K-TIRADS and ACR-TIRADS in stratifying the malignancy risk of thyroid nodules. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 899575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Jung, J.H.; Mandal, T.K. Multimodal AI in Biomedicine: Pioneering the Future of Biomaterials, Diagnostics, and Personalized Healthcare. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.F.; Stafford, L.M.C.; Brys, N.; Greenberg, C.C.; Balentine, C.J.; Elfenbein, D.M.; Pitt, S.C. Gauging the extent of thyroidectomy for indeterminate thyroid nodules: An oncologic perspective. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, X. The Cancer Omics Atlas: An integrative resource for cancer omics annotations. BMC Med. Genom. 2018, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.Z.F.; Adeniran, A.F. Grading and scoring of prominent ears. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 582–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Dong, M.; Wang, Z. Downregulation of TSPAN13 by miR-369-3p inhibits cell proliferation in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC). Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 19, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Junit, S.M.; Ng, K.L.; Jayapalan, J.J.; Karikalan, B.; Hashim, O.H. Papillary thyroid cancer: Genetic alterations and molecular biomarker investigations. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, C.A.; Lozovanu, V.; Silaghi, H.; Georgescu, R.D.; Pop, C.; Dobrean, A.; Georgescu, C.E. The prognostic value of micrornas in thyroid Cancers—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforova, M.N.; Lynch, R.A.; Biddinger, P.W.; Alexander, E.K.; Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Tallini, G.; Kroll, T.G.; Nikiforov, Y.E. RAS point mutations and PAX8-PPARγ rearrangement in thyroid tumors: Evidence for distinct molecular pathways in thyroid follicular carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2318–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintakuntlawar, A.V.; Foote, R.L.; Kasperbauer, J.L.; Bible, K.C. Diagnosis and management of anaplastic thyroid cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 48, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prete, A.; de Souza, P.B.; Censi, S.; Muzza, M.; Nucci, N.; Sponziello, M. Update on fundamental mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Doja, M.; Ahmad, T. Data mining and machine learning in cancer survival research: An overview and future recommendations. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 128, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, E.-H.; Muresan, C.I.; Mocan, T.; Mocan, L. Computer-aided diagnosis system for colorectal cancer. In Proceedings of the 2021 25th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC), Iași, Romania, 20–23 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, T.; Yasin, S.; Draz, U.; Ayaz, M.; Tariq, T.; Javaid, S. Motif Detection in Cellular Tumor p53 Antigen Protein Sequences by using Bioinformatics Big Data Analytical Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.-J. An integrated algorithm for gene selection and classification applied to microarray data of ovarian cancer. Artif. Intell. Med. 2008, 42, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Mao, T.; Zhong, L. Assessment of risk based on variant pathways and establishment of an artificial neural network model of thyroid cancer. BMC Med. Genet. 2019, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iesato, A.; Nucera, C. Role of regulatory non-coding RNAs in aggressive thyroid cancer: Prospective applications of neural network analysis. Molecules 2021, 26, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, P.; Wu, C.-J. Mapping driver mutations to histopathological subtypes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Applying a deep convolutional neural network. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placzek, A.; Pluciennik, A.; Kotecka-Blicharz, A.; Jarzab, M.; Mrozek, D. Bayesian assessment of diagnostic strategy for a thyroid nodule involving a combination of clinical synthetic features and molecular data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 175125–175139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, S.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, S.; Raghava, G.P.S. Expression based biomarkers and models to classify early and late-stage samples of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudova, D.; Wilde, J.I.; Wang, E.T.; Wang, H.; Rabbee, N.; Egidio, C.M.; Reynolds, J.; Tom, E.; Pagan, M.; Rigl, C.T.; et al. Molecular classification of thyroid nodules using high-dimensionality genomic data. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 5296–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, I.-Y.; Kim, B.-C.; Lee, J.; Kang, T.; Garry, D.J.; Zhang, J.; Gong, W. Proformer: A hybrid macaron transformer model predicts expression values from promoter sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneweg, P.; Dandinasivara, R.; Luo, X.; Hammer, B.; Schönhuth, A. Generating synthetic genotypes using diffusion models. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, i484–i492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Min, S.; Vaidya, J. Exploring the use of artificial genomes for genome-wide association studies through the lens of utility and privacy. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; American Medical Informatics Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; p. 1196. [Google Scholar]

- Oprisanu, B.; Ganev, G.; De Cristofaro, E. On Utility and privacy in synthetic genomic data. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Navarro, A.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, W.; Wang, B.; Stein, L. In silico generation of synthetic cancer genomes using generative AI. Cell Genom. 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicoló, V.; Frasca, M.; Graziosi, A.; Gazzaniga, G.; La Torre, D.; Pani, A. Synthetic data generation in genomic cancer medicine: A review of global research trends in the last ten years. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014, 159, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toraih, E.A.; Fawzy, M.S.; Ning, B.; Zerfaoui, M.; Errami, Y.; Ruiz, E.M.; Hussein, M.H.; Haidari, M.; Bratton, M.; Tortelote, G.G.; et al. A miRNA-based prognostic model to trace thyroid cancer recurrence. Cancers 2022, 14, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, Y. Ultrasonic thyroid nodule detection method based on U-Net network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 199, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, Z.; Su, H.; Yang, L.; Zhong, D. Rule-based automatic diagnosis of thyroid nodules from intraoperative frozen sections using deep learning. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 108, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovidis, D.K.; Keramidas, E.G.; Maroulis, D. Fusion of fuzzy statistical distributions for classification of thyroid ultrasound patterns. Artif. Intell. Med. 2010, 50, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danku, A.E.; Dulf, E.H.; Banut, R.P.; Silaghi, H.; Silaghi, A. Cancer diagnosis with the aid of artificial intelligence modeling tools. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 20816–20831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, C.-A.; Dulf, E.H.; Ciobanu, L. Automated detection of celiac disease using Machine Learning Algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, E.-H.; Bledea, M.; Mocan, T.; Mocan, L. Automatic detection of colorectal polyps using transfer learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-X.; Liu, Q.-H.; Hu, Q.-H.; Shi, J.-Y.; Liu, G.-L.; Liu, H.; Shu, S.-C. Ultrasound-based deep learning radiomics nomogram for tumor and axillary lymph node status prediction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.B.; Souza, J.R.; Fernandes, H. CNN architecture optimization using bio-inspired algorithms for breast cancer detection in infrared images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 142, 105205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yu, J.; Liao, J.; Chen, Z. Convolutional neural network for breast and thyroid nodules diagnosis in ultrasound imaging. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1763803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, V.; Jaganathan, D.; Ravi, V.; Velleangiri, V.; Ravi, P. A comparative study on thyroid nodule classification using transfer learning methods. Open Bioinform. J. 2024, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etehadtavakol, M.; Ng, E.Y. Enhanced thyroid nodule segmentation through U-Net and VGG16 fusion with feature engineering: A comprehensive study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 251, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Dass, R.; Virmani, J. Deep learning-based CAD system design for thyroid tumor characterization using ultrasound images. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 43071–43113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Lin, Y. Automatic diagnosis of thyroid ultrasound image based on FCN-AlexNet and transfer learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), Shanghai, China, 19–21 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W.-K.; Sun, J.-H.; Liou, M.-J.; Li, Y.-R.; Chou, W.-Y.; Liu, F.-H.; Chen, S.-T.; Peng, S.-J. Using deep convolutional neural networks for enhanced ultrasonographic image diagnosis of differentiated thyroid cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Yu, R.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H.; Yue, B.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X.; Gao, M.; Wei, X. An efficient deep convolutional neural network model for visual localization and automatic diagnosis of thyroid nodules on ultrasound images. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.; Hur, S.-J.; Park, K.-S.; Kim, H.-J.; Seo, M.; Lee, M.K.; Jung, S.-L.; Jung, C.K. Deep convolutional neural network for classification of thyroid nodules on ultrasound: Comparison of the diagnostic performance with that of radiologists. Eur. J. Radiol. 2022, 152, 110335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.S.; Dai, J.; Chew, W.L.; Cai, Y. The design and engineering of synthetic genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzovici, N.; Dulf, E.-H.; Mocan, T.; Mocan, L. Artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer diagnosis using clinical data: Non-invasive approach. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, N.; Wan, H.; Yao, Q.; Jia, S.; Zhang, X.; Fu, S.; Ruan, J.; He, G.; Chen, X.; et al. Deep learning models for thyroid nodules diagnosis of fine-needle aspiration biopsy: A retrospective, prospective, multicentre study in China. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e458–e469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.; White, R.; Venables, H.; Lam, V.; Vaidhyanath, R. Investigation of artificial intelligence–based clinical decision support system’s performance in reducing the fine needle aspiration rate of thyroid nodules: A pilot study. Ultrasound 2025, 33, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athreya, S.; Melehy, A.; Suthahar, S.S.A.; Ivezić, V.; Radhachandran, A.; Sant, V.R.; Moleta, C.; Zheng, H.; Patel, M.; Masamed, R.; et al. Combining Ultrasound Imaging and Molecular Testing in a Multimodal Deep Learning Model for Risk Stratification of Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules. Thyroid 2025, 35, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Augmentation Technique | Model Accuracy [%] |

|---|---|

| No augmentation | 78.4% |

| Random rotations (±20°) | 81.8% |

| Random translations (±15 pixels) | 82.6% |

| CLAHE | 87.91% |

| Gaussian noise | 90.48% |

| Neural Network | Accuracy [%] | Sensitivity [%] | Specificity [%] | Training Time [min s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALEXNET | 90.48% | 100% | 53.84% | 3 min 32 s |

| DARKNET-19 | 77.78% | 98% | 64.18% | 6 min 08 s |

| VGG-16 | 88.89% | 88% | 92.3% | 10 min 45 s |

| VGG-19 | 93.65% | 100% | 69.23% | 15 min 25 s |

| RESNET-50 | 92.06% | 100% | 61.53% | 18 min 46 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lorenzovici, N.; Silaghi, H.; Dulf, E.-H.; Braicu, C.; Silaghi, C.A. Advanced AI-Powered System for Comprehensive Thyroid Cancer Detection and Malignancy Risk Assessment. Life 2026, 16, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010038

Lorenzovici N, Silaghi H, Dulf E-H, Braicu C, Silaghi CA. Advanced AI-Powered System for Comprehensive Thyroid Cancer Detection and Malignancy Risk Assessment. Life. 2026; 16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorenzovici, Noemi, Horatiu Silaghi, Eva-H. Dulf, Cornelia Braicu, and Cristina Alina Silaghi. 2026. "Advanced AI-Powered System for Comprehensive Thyroid Cancer Detection and Malignancy Risk Assessment" Life 16, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010038

APA StyleLorenzovici, N., Silaghi, H., Dulf, E.-H., Braicu, C., & Silaghi, C. A. (2026). Advanced AI-Powered System for Comprehensive Thyroid Cancer Detection and Malignancy Risk Assessment. Life, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010038