Effect of Heat-Killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on Sleep Quality and Stress-Related Neuroendocrine and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Test Supplements

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Measurements

2.6. Primary Outcome

2.7. Secondary Outcomes

2.8. Safety Endpoints

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

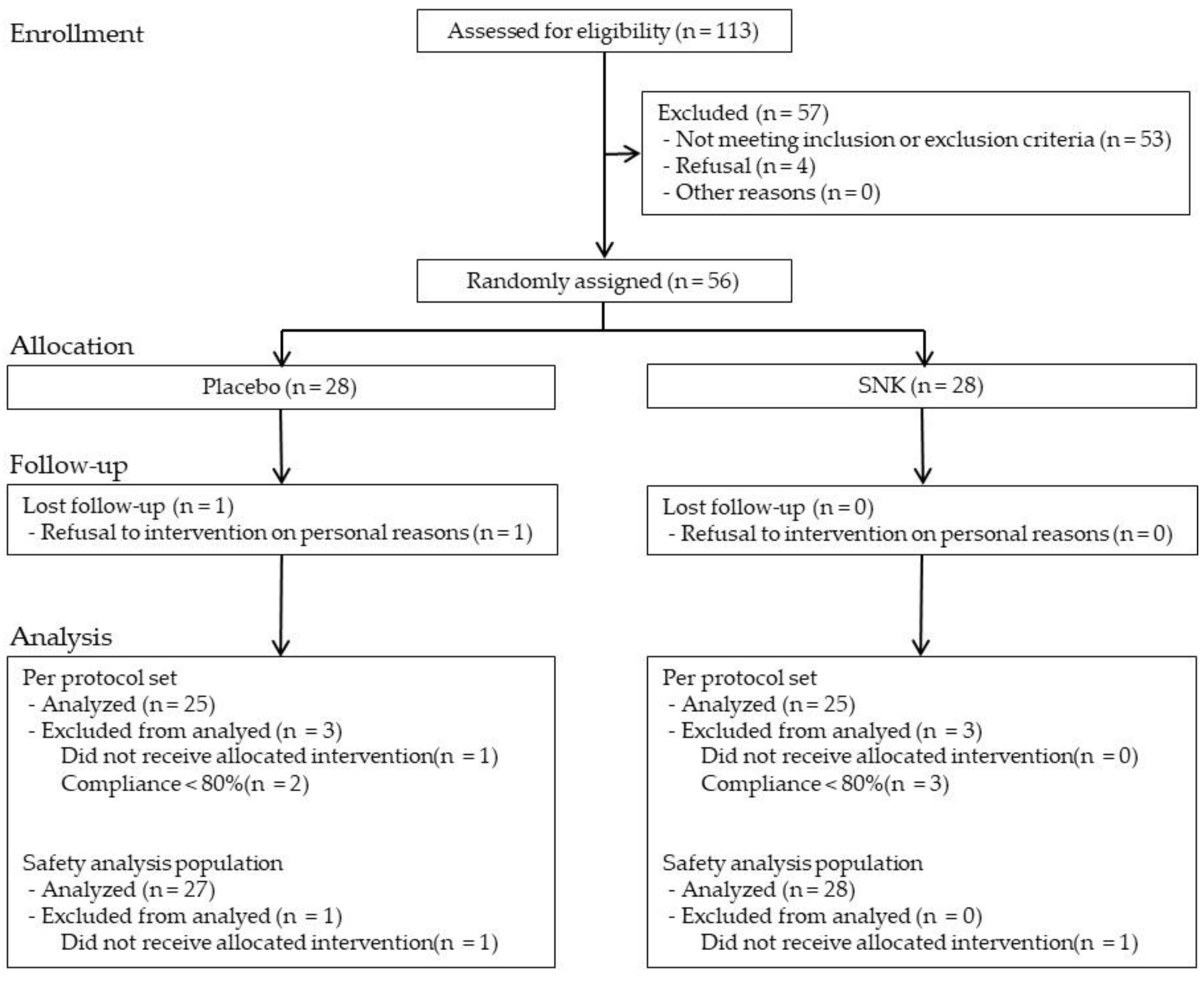

3.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. OSA Sleep Inventory (OSA-MA)

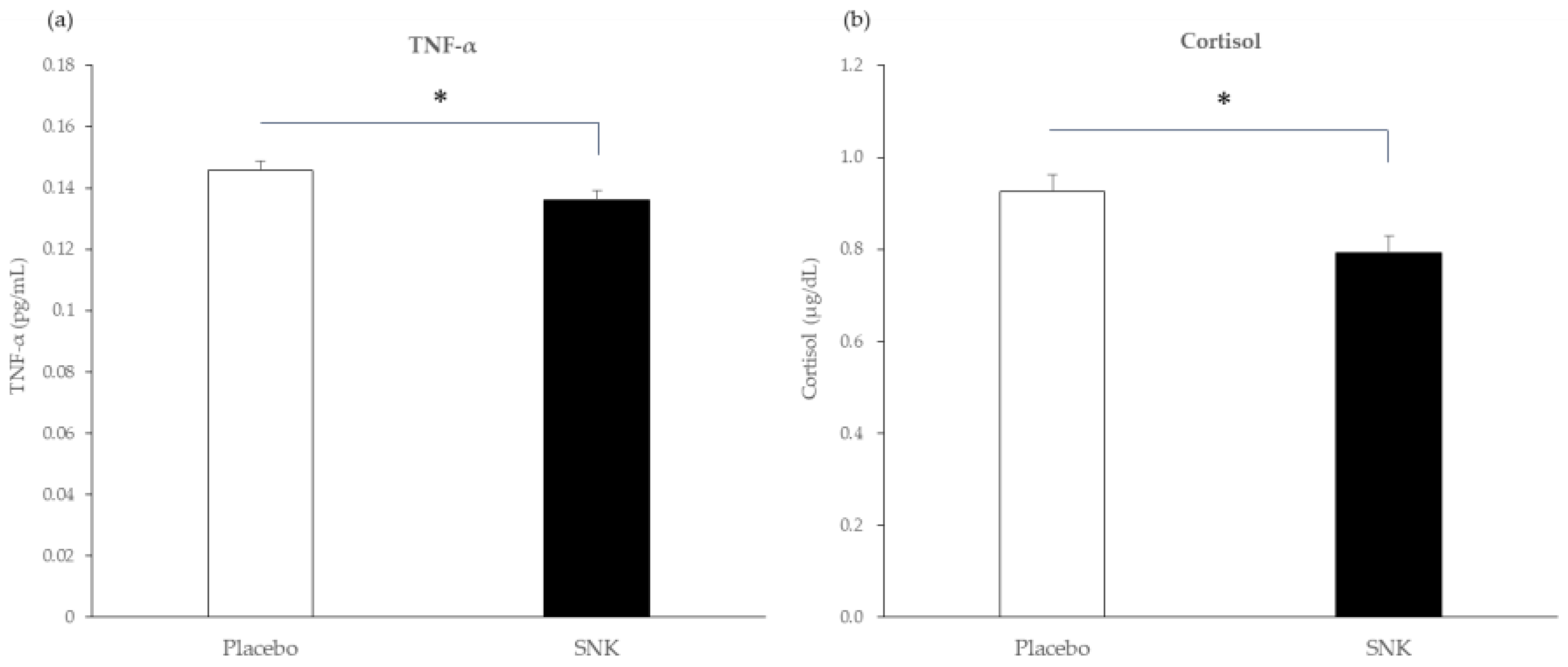

3.3. Blood and Salivary Biomarkers

3.4. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | adverse event |

| ANCOVA | analysis of covariance |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory–II |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| EMM | estimated marginal mean |

| FAS | Full Analysis Set |

| FFC | Foods with Function Claims |

| FOSHU | Foods for Specified Health Uses |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| HPA | hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| LAB | lactic acid bacteria |

| OSA-MA | Oguri–Shirakawa–Azumi Sleep Inventory MA version |

| PPS | Per Protocol Set |

| SAF | Safety Analysis Set |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

| SNK | heat-killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 |

| TEAE | treatment-emergent adverse event |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Grandner, M.A. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep Med. Clin. 2017, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E.H. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, M.; Panigrahi, P.; Kollmann, T.R. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-Nomad and ideal probiotic. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 712236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, N.; Battista, N.; Prete, R.; Corsetti, A. Health-promoting role of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum isolated from fermented foods. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Hayashi, K.; Kan, T.; Ohwaki, M.; Kawahara, T. Anti-influenza virus effects of Enterococcus faecalis KH2 and Lactobacillus plantarum SNK12 RNA. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2021, 40, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, T.; Wakisaka, M.; Watanabe, T.; Nishijima, A.; Ikeda, A.; Teraoka, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, K.; Nishino, N. Specific heat-killed lactic acid bacteria enhance mucosal aminopeptidase N activity in the small intestine of aged mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukahara, T.; Kawase, T.; Yoshida, H.; Bukawa, W.; Kan, T.; Toyoda, A. Preliminary investigation of the effect of oral supplementation of Lactobacillus plantarum strain SNK12 on mRNA levels of neurotrophic factors and GABA receptors in the hippocampus of mice under stress-free and sub-chronic mild social defeat–stressing conditions. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Hayashi, K.; Takara, T.; Teratani, T.; Kitayama, J.; Kawahara, T. Effect of oral administration of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on temporary stress in adults: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamatsu, A.; Yamashita, Y.; Pandharipande, T.; Maru, I.; Kim, M. Effect of oral γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration on sleep and its absorption in humans. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidese, S.; Ogawa, S.; Ota, M.; Ishida, I.; Yasukawa, Z.; Ozeki, M.; Kunugi, H. Effects of L-theanine administration on stress-related symptoms and cognitive functions in healthy adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, M.; Nishida, K.; Gondo, Y.; Kikuchi-Hayakawa, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Suda, K.; Kawai, M.; Hoshi, R.; Kuwano, Y.; Miyazaki, K.; et al. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus casei Strain Shirota on academic stress-induced sleep disturbance in healthy adults: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Ko, T.; Ouchi, H.; Namba, T.; Ebihara, S.; Kobayashi, S. Bifidobacterium adolescentis SBT2786 improves sleep quality in Japanese adults with relatively high levels of stress: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, K.; Itoh, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Higo-Yamamoto, S.; Nakakita, Y.; Kaneda, H.; Shigyo, T.; Oishi, K. Dietary heat-killed Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 promotes voluntary wheel-running and affects sleep rhythms in mice. Life Sci. 2014, 111, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakakita, Y.; Tsuchimoto, N.; Takata, Y.; Nakamura, T. Effect of dietary heat-killed Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 (SBL88™) on sleep: A non-randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, and crossover pilot study. Benef. Microbes 2016, 7, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazoki, O.; Hernandez, S.B.; Cava, F. Peptidoglycan Muropeptides: Release, Perception, and Functions as Signaling Molecules. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Takase, M.; Yamazaki, K.; Azumi, K.; Shirakawa, S. Standardization of revised version of OSA sleep inventory for middle age and aged. Brain Sci. Ment. Disord. 1999, 10, 401–409. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hellhammer, D.H.; Wüst, S.; Kudielka, B.M. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R. Sleep and inflammation: Partners in sickness and in health. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Olmstead, R.; Carroll, J.E. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory—II; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Slavish, D.C.; Szabo, Y.Z. What moderates salivary markers of inflammation reactivity to stress? A descriptive report and meta-regression. Stress 2021, 24, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.R.; Talge, N.M.; Herrera, A. Stressor paradigms in developmental studies: What does and does not work to produce mean increases in salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, A.; Kecklund, G.; Åkerstedt, T. Different levels of work-related stress and the effects on sleep, fatigue and cortisol. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM. SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ICH Expert Working Group. ICH Harmonised Tripartite, 1999 Guideline E9: Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials; ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, A.J. Parametric versus non-parametric statistics in the analysis of randomized trials with non-normally distributed data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Statist. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, M.D.; Chen, L.; Taishi, P.; Nguyen, J.T.; Gibbons, C.M.; Veasey, S.C.; Krueger, J.M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha in sleep regulation. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 40, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, S.; Besedovsky, L.; Born, J.; Lange, T. Differential acute effects of sleep on spontaneous and stimulated production of tumor necrosis factor in men. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 47, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Zoumakis, E.; Lin, H.M.; Bixler, E.O.; Trakada, G.; Chrousos, G.P. Marked decrease in sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea by etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 4409–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Song, Y.; Ning, P.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Quan, J.; Li, Q. Association between tumor necrosis factor alpha and obstructive sleep apnea in adults: A meta-analysis update. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekedulegn, D.; Innes, K.; Andrew, M.E.; Tinney-Zara, C.; Charles, L.E.; Allison, P.; Violanti, J.M.; Knox, S.S. Sleep quality and the cortisol awakening response (CAR) among law enforcement officers: The moderating role of leisure time physical activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 95, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Badrick, E.; Ferrie, J.; Perski, A.; Marmot, M.; Chandola, T. Self-reported sleep duration and sleep disturbance are independently associated with cortisol secretion in the Whitehall II study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4801–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsonne, G.; Lekander, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Axelsson, J.; Ingre, M. Diurnal variation of circulating interleukin-6 in humans: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Papanicolaou, D.A.; Bixler, E.O.; Lotsikas, A.; Zachman, K.; Kales, A.; Prolo, P.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J.; Gold, P.W.; et al. Circadian interleukin-6 secretion and quantity and depth of sleep. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 2603–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugué, B.; Leppänen, E. Short-term variability in the concentration of serum interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor in subjectively healthy persons. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 1998, 36, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, L.-C.; Hor, Y.-Y.; Yusoff, N.A.A.; Choi, S.-B.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Roslan, N.S.; Ahmad, A.; Mohammad, J.A.M.; Abdullah, M.F.I.L.; Zakaria, N.; et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum P8 alleviated stress and anxiety while enhancing memory and cognition in stressed adults: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2053–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, Y.; Murosaki, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoshikai, Y.; Tsuru, T. Daily intake of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 augments acquired immunity in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 3069–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Ze, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, S.; Jia, W.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei 207–27 alters the microbiota–gut–brain axis to improve wearable device–measured sleep duration in healthy adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 10732–10745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A.; Samman, S.; Galland, B.; Foster, M. Daily consumption of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 improves quality of sleep in adults—A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Placebo (n = 25) | SNK (n = 25) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (male/female) | 10/15 | 9/16 | 1.000 |

| Age, years | 49.6 ± 9.8 | 48.6 ± 9.6 | 0.923 |

| Height, cm | 162.7 ± 9.2 | 161.8 ± 7.7 | 0.923 |

| Weight, kg | 56.5 ± 11.8 | 53.6 ± 11.6 | 0.494 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21.2 ± 3.2 | 20.3 ± 3.2 | 0.503 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 117.4 ± 19.7 | 115.2 ± 18.6 | 0.971 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73.1 ± 11.0 | 74.9 ± 12.5 | 0.347 |

| BDI-II total score | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 10.2 ± 5.6 | 0.787 |

| Sleepiness on rising score | 14.6 ± 2.8 | 14.0 ± 3.1 | 0.786 |

| Collection time at baseline | 10:24 (SD 64.2) | 10:18 (SD 41.5) | 0.697 |

| Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Week 4 (Mean ± SD) | Adjusted Week 4 (EMM ± SE) | Between-Group Difference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Placebo | SNK | Placebo | SNK | Placebo | SNK | Δ (SNK − Placebo) | SE | 95% CI− | 95% CI+ | p-Value |

| Sleepiness on Rising | 14.6 ± 2.8 | 14.0 ± 3.1 | 16.6 ± 5.5 | 18.9 ± 3.0 | 16.4 ± 0.8 | 19.1 ± 0.8 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 5.1 | 0.032 |

| Initiation and Maintenance of Sleep | 14.9 ± 3.1 | 14.4 ± 3.7 | 15.5 ± 4.7 | 18.8 ± 4.6 | 15.4 ± 0.9 | 18.9 ± 0.9 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 0.010 |

| Frequent Dreaming | 21.7 ± 6.2 | 21.4 ± 5.4 | 20.9 ± 7.1 | 22.1 ± 7.1 | 20.8 ± 1.4 | 22.1 ± 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.9 | −2.6 | 5.2 | 0.502 |

| Refreshing | 13.7 ± 3.7 | 13.8 ± 3.2 | 17.3 ± 4.8 | 17.8 ± 4.5 | 17.4 ± 0.9 | 17.8 ± 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 | −2.1 | 3.0 | 0.710 |

| Sleep Length | 15.1 ± 4.7 | 15.9 ± 3.3 | 19.3 ± 3.4 | 18.8 ± 4.4 | 19.4 ± 0.7 | 18.6 ± 0.7 | −0.8 | 1.0 | −2.8 | 1.2 | 0.428 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Watanabe, T.; Kurosaka, S.; Namatame, Y.; Kawahara, T. Effect of Heat-Killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on Sleep Quality and Stress-Related Neuroendocrine and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Trial. Life 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010026

Watanabe T, Kurosaka S, Namatame Y, Kawahara T. Effect of Heat-Killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on Sleep Quality and Stress-Related Neuroendocrine and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Trial. Life. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatanabe, Takumi, Shiho Kurosaka, Yuriko Namatame, and Toshio Kawahara. 2026. "Effect of Heat-Killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on Sleep Quality and Stress-Related Neuroendocrine and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Trial" Life 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010026

APA StyleWatanabe, T., Kurosaka, S., Namatame, Y., & Kawahara, T. (2026). Effect of Heat-Killed Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SNK12 on Sleep Quality and Stress-Related Neuroendocrine and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Trial. Life, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010026