ISSR-Based Genetic Diversity and Structure of Medicago sativa L. Populations from the Aras Basin, a Crossroad of Gene Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

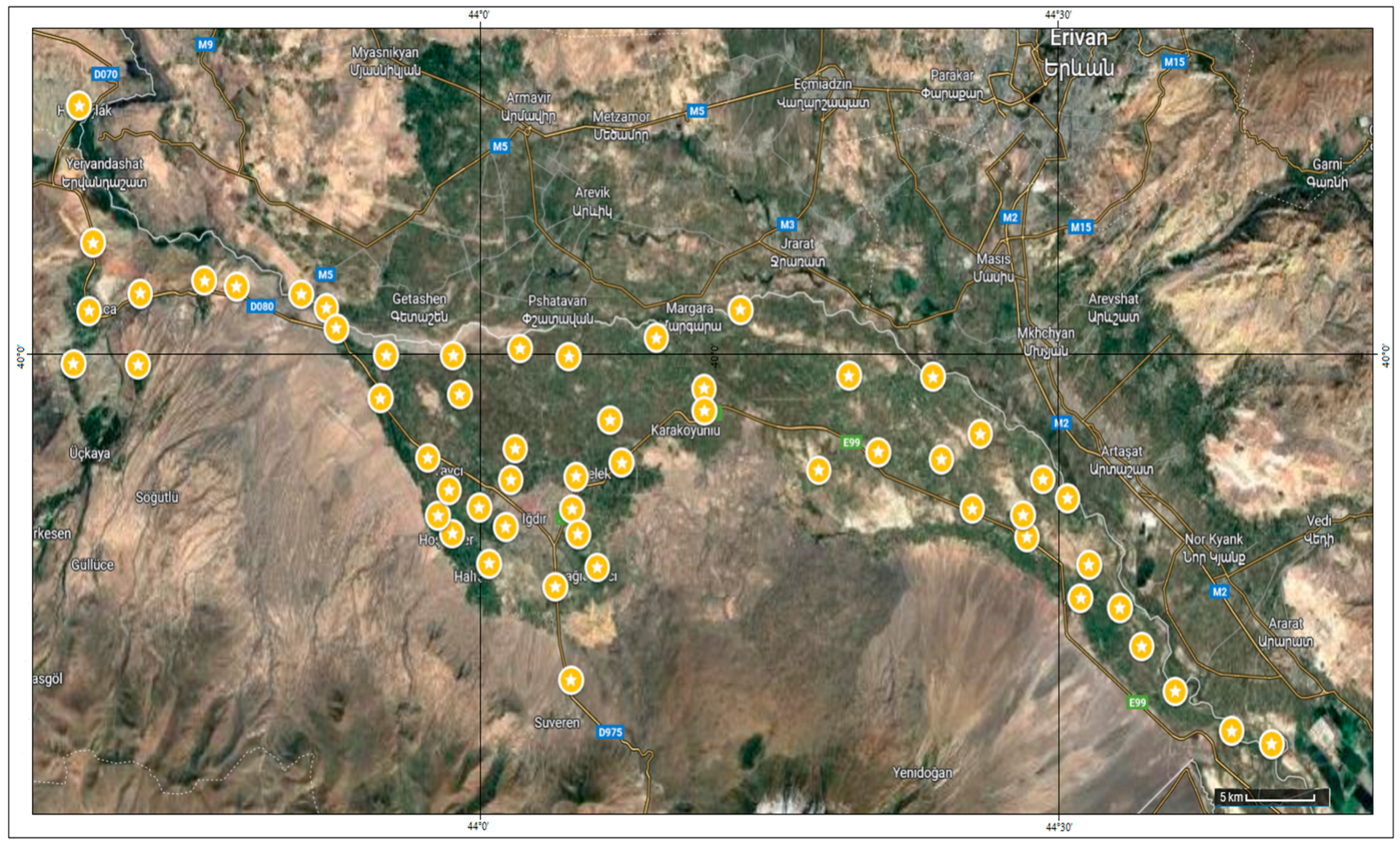

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. DNA Extraction and Quantification

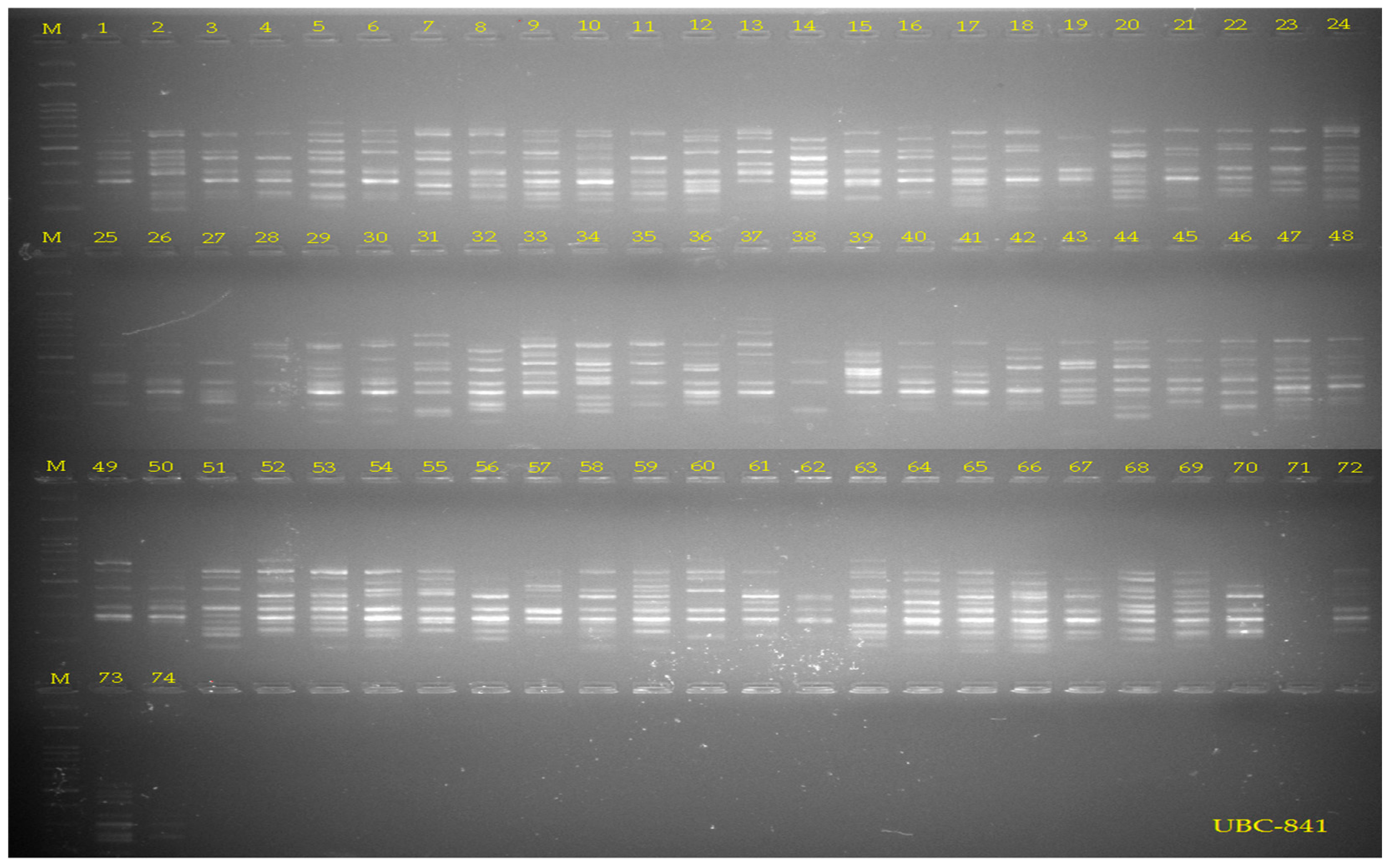

2.3. ISSR Analyses

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. DNA Polymorphism and Genetic Diversity

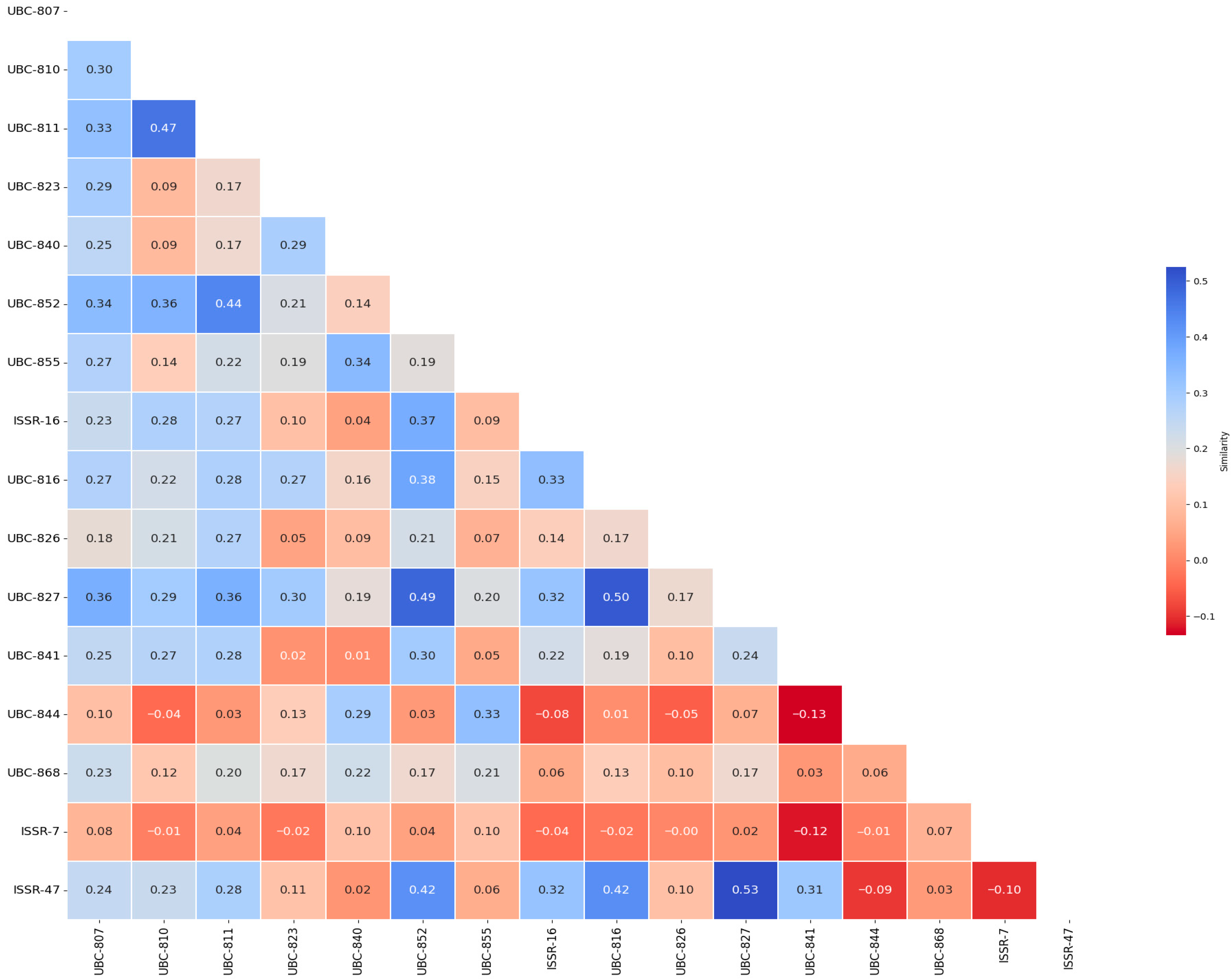

3.2. Genetic Similarity Heat Map Among Primers

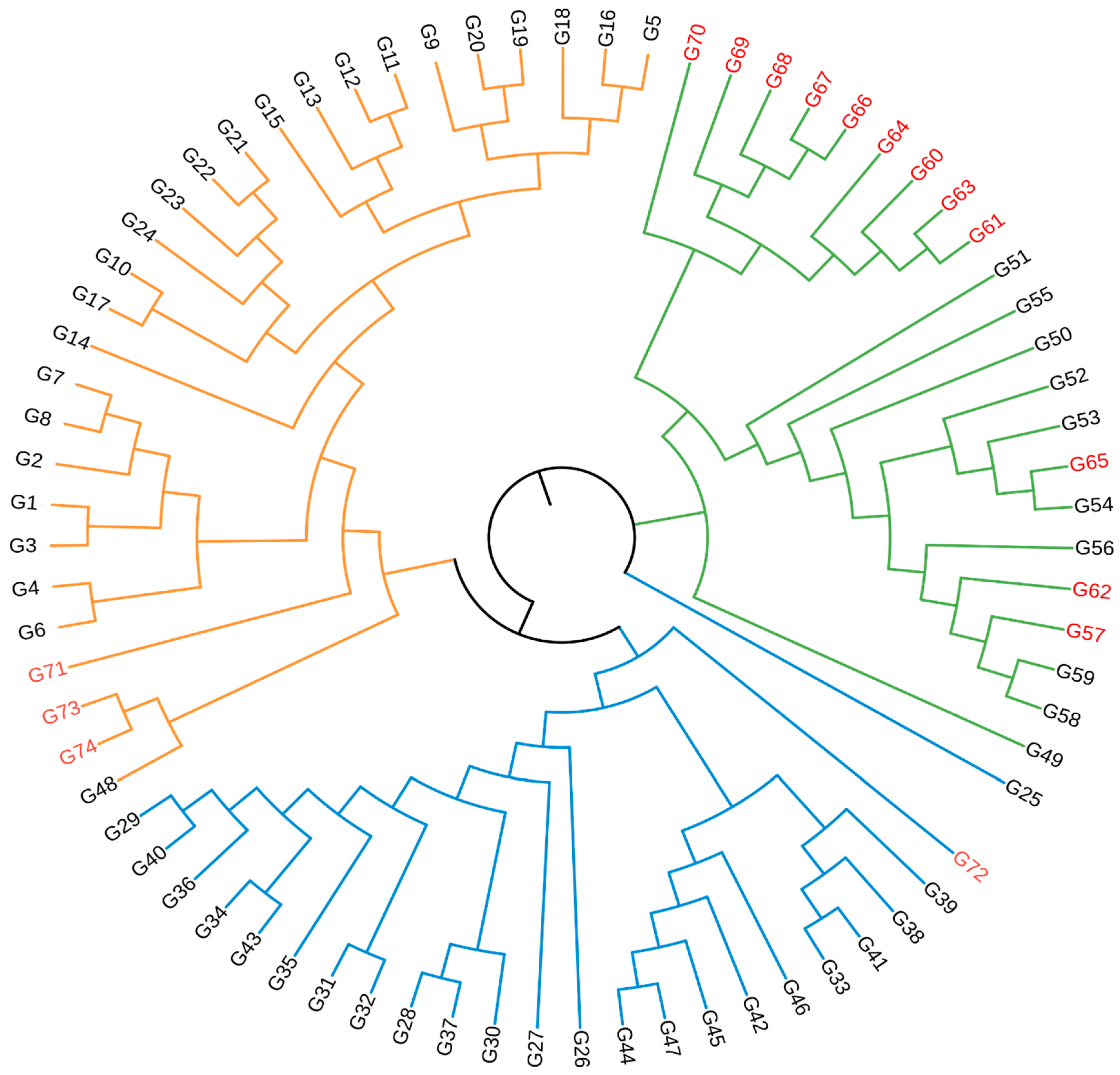

3.3. Cluster Analysis and Population Structure

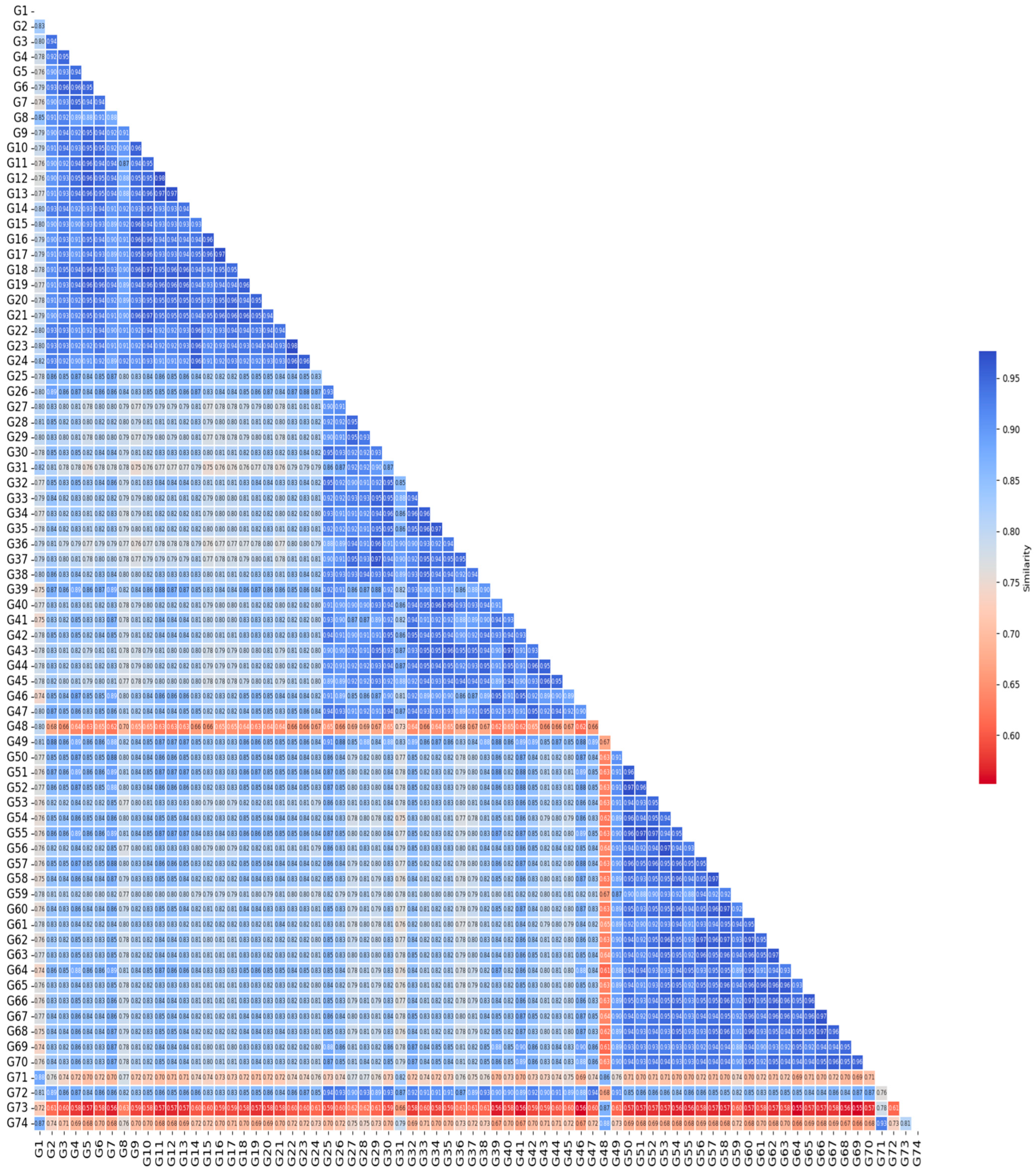

3.4. Jaccard Similarity Heat Map Among Genotypes

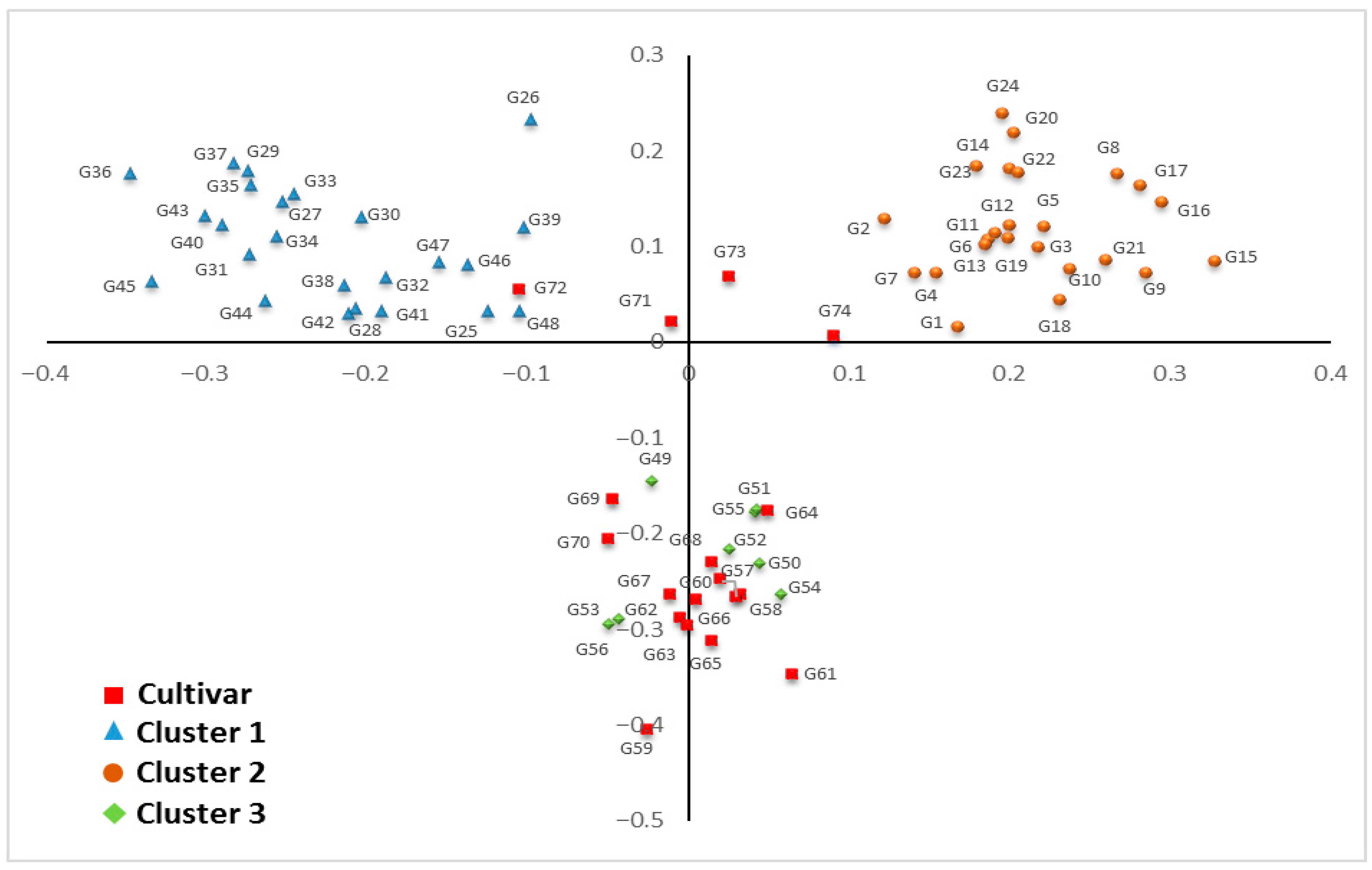

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCoA)

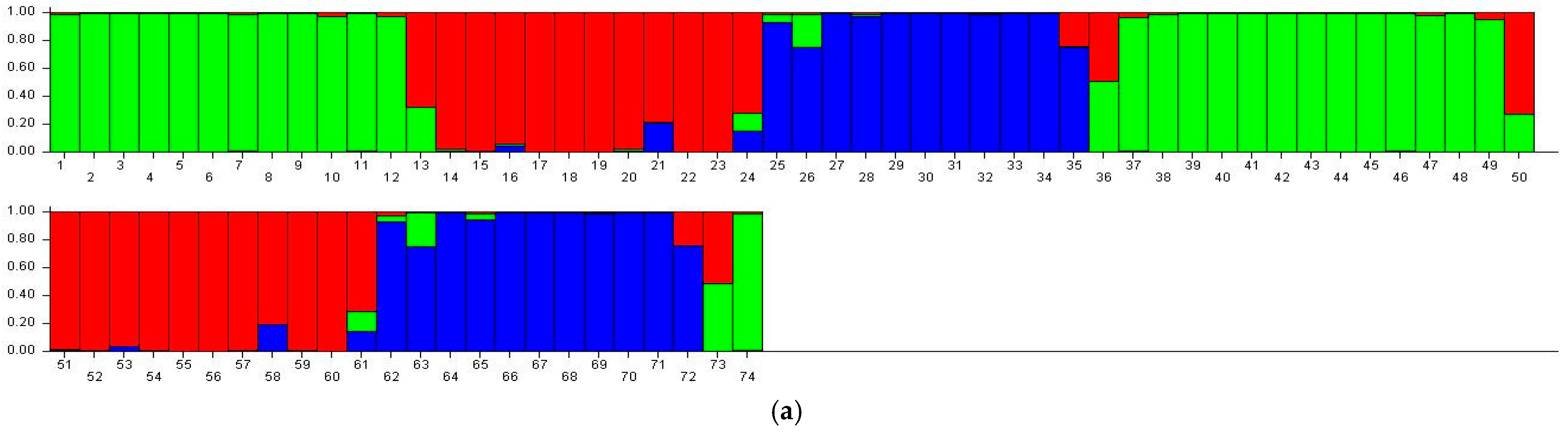

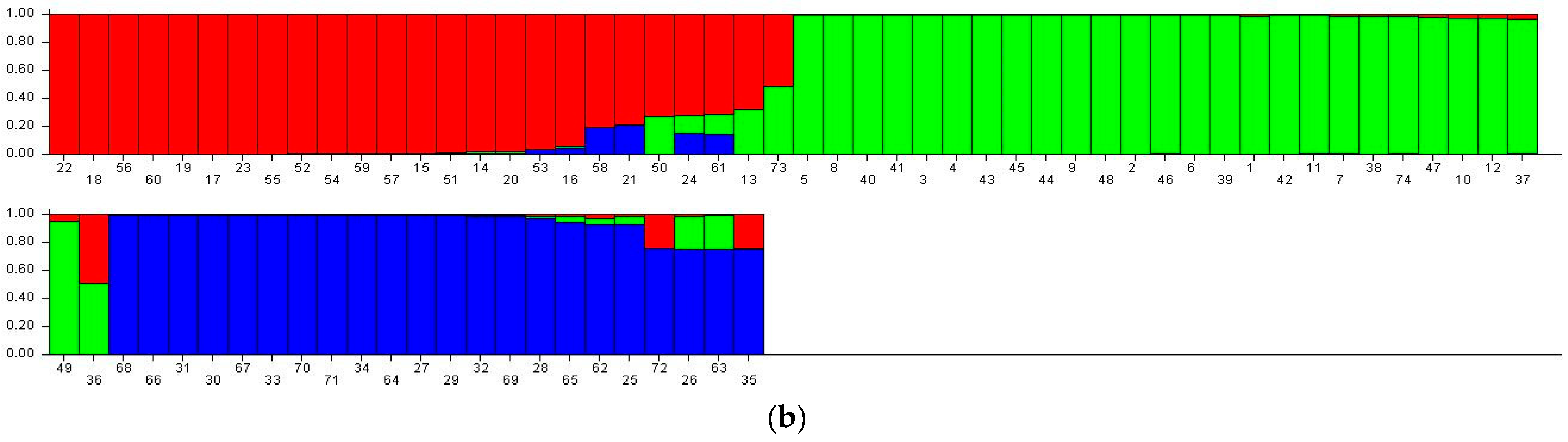

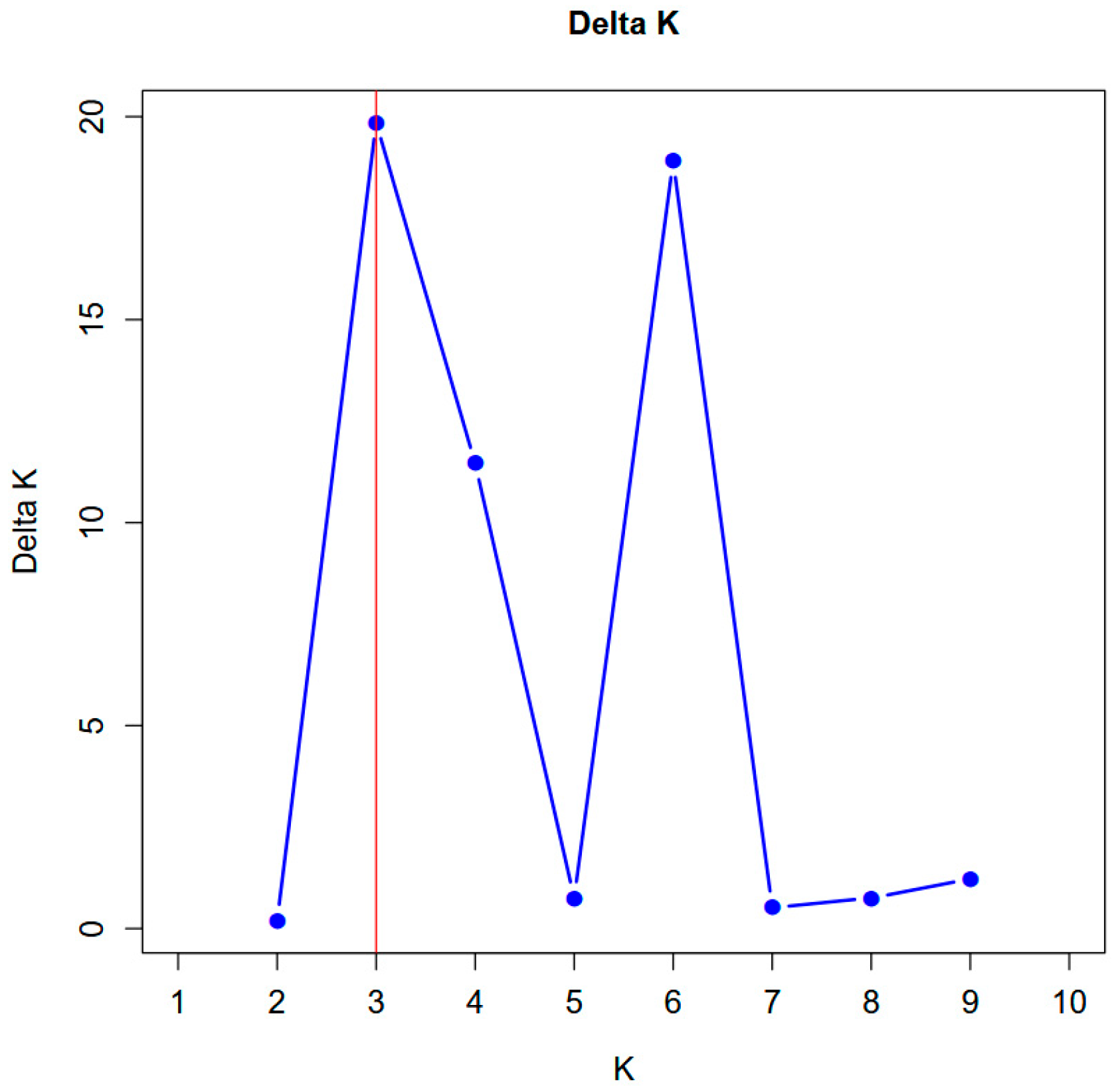

3.6. STRUCTURE Analysis

3.7. Distribution of Genetic Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISSR | Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinate Analysis |

| UPGMA | Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean |

| PIC | Polymorphism Information Content |

| CTAB | Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide |

| He | Nei’s Genetic Diversity (Expected Heterozygosity) |

| Ne | Effective Number of Alleles |

| Rp | Resolving Power |

| ΔK | Delta K (Evanno method index for STRUCTURE analysis) |

References

- Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Guo, C.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, X.; Wang, W. Simple Sequence Repeat-Based Genetic Diversity Analysis of Alfalfa Varieties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO Statistical Database; FAO: Faro, Portugal, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- He, Q.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, Z.P.; Sun, S.S.; Zhan, Q.W. Genetic diversity in the worldwide alfalfa germplasm assessed through SSR markers. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 22, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, B.; Keskin, B.; Demirel, F.; Demirel, S.; Türkoğlu, A.; Yilmaz, A.; Haliloğlu, K. Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure in local alfalfa genotypes using iPBS molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2023, 70, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, M.İ.; Türkoğlu, A.; Demirel, F.; Aydın, A.; Eren, B.; Koç, A.; Armağan, M.; Haliloğlu, K.; Yaman, M.; Bocianowski, J. Genetic diversity and genetic structure of alfalfa (M. sativa L.) genotypes as revealed by Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 10543–10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petolescu, C.; Sarac, I.; Popescu, S.; Tenche-Constantinescu, A.M.; Petrescu, I.; Camen, D.; Onisan, E. Assessment of Genetic Diversity in Alfalfa Using DNA Polymorphism Analysis and Statistical Tools. Plants 2024, 13, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcılar, B.; Jannati, G.; Bezirganoglu, I. Genetic Variations in Turkey Cultivar and Ecotype M. sativa Species: Cytological, Total Protein Profile, and Molecular Characterization. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiroglu, M.; Charles Brummer, E. Presence of phylogeographic structure among wild diploid alfalfa accessions (M. sativa L. subsp. microcarpa Urb.) with evidence of the center of origin. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilov, N.I. The Origin, Variation, İmmunity and Breeding of Cultivated Plants; LWW: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1951; Volume 72, p. 482. [Google Scholar]

- Noroozi, J.; Zare, G.; Sherafati, M.; Mahmoodi, M.; Moser, D.; Asgarpour, Z.; Schneeweiss, G.M. Patterns of endemism in Turkey, the meeting point of three global biodiversity hotspots, based on three diverse families of vascular plants. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basbag, M.; Aydin, A.; Sakiroglu, M. Evaluating agronomic performance and investigating molecular structure of drought and heat tolerant wild alfalfa (M. sativa L.) collection from the Southeastern Turkey. Biochem. Genet. 2017, 55, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesins, K.; Gillies, C.B. Taxonomy and cytogenetics of Medicago. Alfalfa Sci. Technol. 1972, 15, 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lesins, K.A.; Lesins, I. Genus Medicago (Leguminosae): A Taxogenetic Study; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. Alfalfa and Relatives: Evolution and Classification of Medicago; NRC Research Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lesins, K.A.; Lesins, I. General key to Medicago species. In Genus Medicago (Leguminosae)—A Taxogenetic Study; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 62–215. [Google Scholar]

- Quiros, C.F.; Bauchan, G.R. The genus Medicago and the origin of the M. sativa complex. In Alfalfa and Alfalfa İmprovement; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1988; Volume 29, pp. 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- Şakiroğlu, M.; İlhan, D.M. sativa species complex: Revisiting the century-old problem in the light of molecular tools. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiroglu, M.; Brummer, E.C. Identification of loci controlling forage yield and nutritive value in diploid alfalfa using GBS-GWAS. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, D.; Li, X.; Brummer, E.C.; Şakiroğlu, M. Genetic diversity and population structure of tetraploid accessions of the M. sativa –falcata Complex. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Brummer, E.C. Applied genetics and genomics in alfalfa breeding. Agronomy 2012, 2, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiroglu, M.; Doyle, J.J.; Brummer, E.C. The population genetic structure of diploid M. sativa L. germplasm. In Sustainable Use of Genetic Diversity in Forage and Turf Breeding; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mnafgui, W.; Jabri, C.; Sakiroglu, M.; Ludidi, N.; Badri, M. Identification of genetic basis of agronomic traits in alfalfa (M. sativa subsp. sativa) using Genome Wide Association Studies. J. Oasis Agric. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 5, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiteye, S. Basic concepts and methodologies of DNA marker systems in plant molecular breeding. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, D. Molecular markers and their applications in marker-assisted selection (MAS) in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agriculture 2023, 13, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Das, S.P.; Choudhury, B.U.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, N.R.; Verma, R.; Chakraborti, M.; Devi, A.G.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Das, R.; et al. Advances in genomic tools for plant breeding: Harnessing DNA molecular markers, genomic selection, and genome editing. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.J. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 1990, 12, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.C. POPGENE (Version 1.3.1). Microsoft Windows-Based Freeware for Population Genetic Analysis; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F.J. NTSYS-pc: Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System; Exeter Publishing: Exeter, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A Web-Based Software to Select and Visualize the Optimal Number of Clusters Using Multiple Methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M.; Milligan, B.G. Analysis of population genetic structure with RAPD markers. Mol. Ecol. 1994, 3, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botstein, D.; White, R.L.; Skolnick, M.; Davis, R.W. Construction of a Genetic Linkage Map in Man Using Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980, 32, 314–331. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Prevost, A.; Wilkinson, M.J. A New System of Comparing PCR Primers Applied to ISSR Fingerprinting of Potato Cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, D. Comparison of Tetraploid Alfalfa (M. sativa L.) Populations Collected from Turkey and Former Soviet Countries. J. Agric. 2022, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfort, J.; Bataillon, T.; Santoni, S.; Delalande, M.; David, J.L.; Prosperi, J.M. Microsatellite diversity and broad-scale geographic structure in a model legume: Building a set of nested core collections for studying naturally occurring variation in Medicago truncatula. BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.D.; Debellé, F.; Oldroyd, G.E.; Geurts, R.; Cannon, S.B.; Udvardi, M.K.; Benedito, V.A.; Mayer, K.F.X.; Gouzy, J.; Schoof, H.; et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature 2011, 480, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gecer, M.K.; Kan, T.; Gundogdu, M.; Ercisli, S.; Ilhan, G.; Sagbas, H.I. Physicochemical Characteristics of Wild and Cultivated Apricots (Prunus armeniaca L.) from Aras Valley in Turkey. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Genetic Variation and Genome–Environment Association of Alfalfa (M. sativa L.) Populations Under Long-Term Grazing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farshadfar, M.; Rashidi, M.; Safari, H.; Shirvani, H. Study of genetic diversity among 17 populations of alfalfa (M. sativa ) using cytogenetic and ISSR molecular markers. Iran. J. Rangel. For. Plant Breed. Genet. Res. 2016, 24, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mint Abdelaziz, S.; Medraoui, L.; Alami, M.; Pakhrou, O.; Makkaoui, M.; Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary, A.; Filali-Maltouf, A. Inter simple sequence repeat markers to assess genetic diversity of the desert date (Balanites aegyptiaca Del.) for Sahelian ecosystem restoration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serttaş, P.T.; Özcan, T. Intraspecific variations studied by ISSR and IRAP markers in mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus L.) from Turkey. Trakya Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2018, 19, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K.U.; Paydas-Kargi, S.; Dogan, Y.; Kafkas, S. Genetic diversity analysis based on ISSR, RAPD and SSR among Turkish apricot germplasms in Iran Caucasian eco-geographical group. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 138, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, Z. Molecular diversity and population structure of a worldwide collection of cultivated tetraploid alfalfa (M. sativa subsp. sativa L.) germplasm as revealed by microsatellite markers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, O.R.; Alshehri, M.A.; Alasmari, A.; Ibrahim, S.D.; Oyouni, A.A.; Siddiqui, Z.H. Evaluation of genetic diversity among Saudi Arabian and Egyptian cultivars of alfalfa (M. sativa L.) using ISSR and SCoT markers. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2023, 17, 2194187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanov, M. Microsatellite Marker-Based Genetic Diversity Analysis and Developing Synthetic Varieties in Alfalfa (M. sativa L.). Master’s Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haliloglu, K.; Turkoglu, A.; Tan, M.; Poczai, P. SSR-based molecular identification and population structure analysis for forage pea (Pisum sativum var. arvense L.) landraces. Genes 2022, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Location | Trait | No. | Province | Trait | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 39°46′59.5″ N 44°40′54.1″ E | Wild | G38 | 40°00′20.5″ N 43°58′24.3″ E | Wild | |

| G2 | 39°47′26.9″ N 44°38′50.2″ E | Wild | G39 | 39°56′49.5″ N 43°57′04.9″ E | Wild | |

| G3 | 39°48′48.5″ N 44°35′53.5″ E | Wild | G40 | 39°54′13.7″ N 43°58′21.5″ E | Wild | |

| G4 | 39°50′21.3″ N 44°34′09.1″ E | Wild | G41 | 39°55′43.3″ N 43°58′10.9″ E | Wild | |

| G5 | 39°51′40.5″ N 44°33′02.0″ E | Wild | G42 | 39°54′50.5″ N 43°57′36.6″ E | Wild | |

| G6 | 39°53′09.3″ N 44°31′25.0″ E | Wild | G43 | 39°58′59.9″ N 43°58′44.5″ E | Wild | |

| G7 | 39°52′00.7″ N 44°30′58.9″ E | Wild | G44 | 40°00′34.7″ N 44°01′52.4″ E | Wild | |

| G8 | 39°55′26.4″ N 44°30′18.3″ E | Wild | G45 | 39°57′08.9″ N 44°01′37.4″ E | Wild | |

| G9 | 39°54′06.3″ N 44°28′11.7″ E | Wild | G46 | 39°53′11.6″ N 44°00′15.9″ E | Wild | |

| G10 | 39°56′05.5″ N 44°29′01.0″ E | Wild | G47 | 39°55′07.3″ N 43°59′45.4″ E | Wild | |

| G11 | 39°54′51.1″ N 44°27′59.6″ E | Wild | G48 | 39°52′24.2″ N 44°03′42.2″ E | Wild | |

| G12 | 39°57′38.7″ N 44°25′46.1″ E | Wild | G49 | 39°55′04.3″ N 44°04′34.3″ E | Wild | |

| G13 | 39°55′04.9″ N 44°25′21.9″ E | Wild | G50 | 39°49′11.5″ N 44°04′31.4″ E | Wild | |

| G14 | 39°56′46.3″ N 44°23′45.6″ E | Wild | G51 | 39°53′04.1″ N 44°05′53.1″ E | Wild | |

| G15 | 39°59′36.9″ N 44°23′19.1″ E | Wild | G52 | 39°56′11.0″ N 44°04′46.7″ E | Wild | |

| G16 | 39°57′01.5″ N 44°20′28.7″ E | Wild | G53 | 39°54′12.4″ N 44°04′53.6″ E | Wild | |

| G17 | 39°59′38.7″ N 44°18′57.2″ E | Wild | G54 | 39°56′04.1″ N 44°01′23.4″ E | Wild | |

| G18 | 39°56′24.2″ N 44°17′22.7″ E | Wild | G55 | 39°54′27.4″ N 44°01′07.6″ E | Wild | |

| G19 | 40°01′54.2″ N 44°13′18.9″ E | Wild | G56 | 39°56′39.7″ N 44°07′08.9″ E | Wild | |

| G20 | 39°59′12.2″ N 44°11′25.4″ E | Wild | G57 | Sunter | Mutlu Seed Industry and Trade Co., Ltd. Konya/Türkiye | |

| G21 | 39°58′26.5″ N 44°11′26.9″ E | Wild | G58 | Kayseri | Local genotype, Kayseri/Türkiye | |

| G22 | 40°00′56.6″ N 44°08′56.6″ E | Wild | G59 | Magna-601 | Biotek Seed Agri. Prod. Ind. & Trade Inc. Konya/Türkiye | |

| G23 | 40°00′18.4″ N 44°04′24.1″ E | Wild | G60 | La Torre | Maro Agri. Constr. Trade & Ind. Inc. Ankara/Türkiye | |

| G24 | 39°58′07.2″ N 44°06′32.6″ E | Wild | G61 | Savaş | East Anatolian Agricultural Research Inst. Erzurum/Türkiye | |

| G25 | 40°08′54.2″ N 43°38′58.1″ E | Wild | G62 | Q. Neobi | NEOBI Seed Inc. İzmir/Türkiye | |

| G26 | 40°04′12.6″ N 43°39′41.4″ E | Wild | G63 | May İside | May-Agro Seed Co. Bursa/Türkiye | |

| G27 | 40°01′52.3″ N 43°39′29.3″ E | Wild | G64 | La Bella | Samen-Unternehmung C. Böhrer Austrian | |

| G28 | 40°02′28.1″ N 43°42′08.1″ E | Wild | G65 | Magnum | Biotek Seed Agri. Prod. Ind. & Trade Konya/Türkiye | |

| G29 | 40°00′03.2″ N 43°38′40.6″ E | Wild | G66 | Prosementi | Tasaco Agriculture Industry and Trade Inc. Antalya/Türkiye | |

| G30 | 40°00′01.5″ N 43°42′01.5″ E | Wild | G67 | Gea | Maro Agri. Constr. Trade & Ind. Inc. Ankara/Türkiye | |

| G31 | 40°02′54.6″ N 43°45′28.2″ E | Wild | G68 | Elçi | Ankara University Faculty of Agriculture, Ankara/Türkiye | |

| G32 | 40°02′42.2″ N 43°47′09.0″ E | Wild | G69 | Plato | Kazak Agri. Constr. & Transport Ind. & Trade Inc. Ankara/Türkiye | |

| G33 | 40°02′26.7″ N 43°50′30.6″ E | Wild | G70 | Giulia | Mutlu Seed Industry and Trade Co., Ltd. Konya/Türkiye | |

| G34 | 40°01′58.5″ N 43°51′49.2″ E | Wild | G71 | Emiliana | Palmiye Seed Agri. Ind. & Trade Co., Ltd. İzmir/ Türkiye | |

| G35 | 39°58′52.5″ N 43°54′37.4″ E | Wild | G72 | Ezzelina | Alfa Seed Agri-Food-Const-Live. Trade Ltd. Larissa/Greece | |

| G36 | 40°01′16.8″ N 43°52′20.0″ E | Wild | G73 | Bilensoy-80 | Field Crops Central Research Institute, Ankara/Türkiye | |

| G37 | 40°00′21.1″ N 43°54′54.6″ E | Wild | G74 | Gacer | Iğdır local genotype, Iğdır/Türkiye | |

| No. | Marker | Primer Seq. | AB | PB | %P | PIC | I | Ne | Rp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UBC-807 | (AG)8 T | 14 | 14 | 100 | 0.277 | 0.630 | 1.432 | 0.620 |

| 2 | UBC-810 | (CA)8 T | 10 | 10 | 100 | 0.334 | 0.727 | 1.550 | 0.535 |

| 3 | UBC-811 | (GA)8 C | 8 | 8 | 100 | 0.206 | 0.503 | 1.287 | 0.750 |

| 4 | UBC-823 | (GA)8 C | 7 | 7 | 100 | 0.141 | 0.374 | 1.175 | 0.842 |

| 5 | UBC-840 | (GA)8 TT | 6 | 6 | 100 | 0.244 | 0.549 | 1.385 | 0.676 |

| 6 | UBC-852 | (TC)8 AA | 12 | 12 | 100 | 0.237 | 0.552 | 1.358 | 0.691 |

| 7 | UBC-855 | (AC)8 YT | 8 | 8 | 100 | 0.218 | 0.529 | 1.298 | 0.740 |

| 8 | ISSR-16 | (GTGC)4 | 8 | 8 | 100 | 0.200 | 0.476 | 1.319 | 0.720 |

| 9 | UBC-816 | (GA)8 T3 | 17 | 17 | 100 | 0.230 | 0.542 | 1.337 | 0.711 |

| 10 | UBC-826 | (GA)8 C3 | 17 | 17 | 100 | 0.260 | 0.606 | 1.387 | 0.661 |

| 11 | UBC-827 | (CA)8 G | 17 | 17 | 100 | 0.236 | 0.548 | 1.361 | 0.688 |

| 12 | UBC-841 | (GA)8 YC | 23 | 23 | 100 | 0.293 | 0.651 | 1.473 | 0.591 |

| 13 | UBC-844 | (CT)8 AC | 6 | 6 | 100 | 0.205 | 0.483 | 1.314 | 0.730 |

| 14 | UBC-868 | (GAA)6 | 12 | 12 | 100 | 0.269 | 0.609 | 1.418 | 0.644 |

| 15 | ISSR-7 | (TC)8 C | 15 | 15 | 100 | 0.222 | 0.541 | 1.302 | 0.735 |

| 16 | ISSR-47 | (AG)8 Y | 33 | 33 | 100 | 0.285 | 0.640 | 1.457 | 0.609 |

| Mean | 213 | 213 | 0.241 | 0.560 | 1.366 | 0.684 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eren, B. ISSR-Based Genetic Diversity and Structure of Medicago sativa L. Populations from the Aras Basin, a Crossroad of Gene Centers. Life 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010021

Eren B. ISSR-Based Genetic Diversity and Structure of Medicago sativa L. Populations from the Aras Basin, a Crossroad of Gene Centers. Life. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleEren, Baris. 2026. "ISSR-Based Genetic Diversity and Structure of Medicago sativa L. Populations from the Aras Basin, a Crossroad of Gene Centers" Life 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010021

APA StyleEren, B. (2026). ISSR-Based Genetic Diversity and Structure of Medicago sativa L. Populations from the Aras Basin, a Crossroad of Gene Centers. Life, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010021