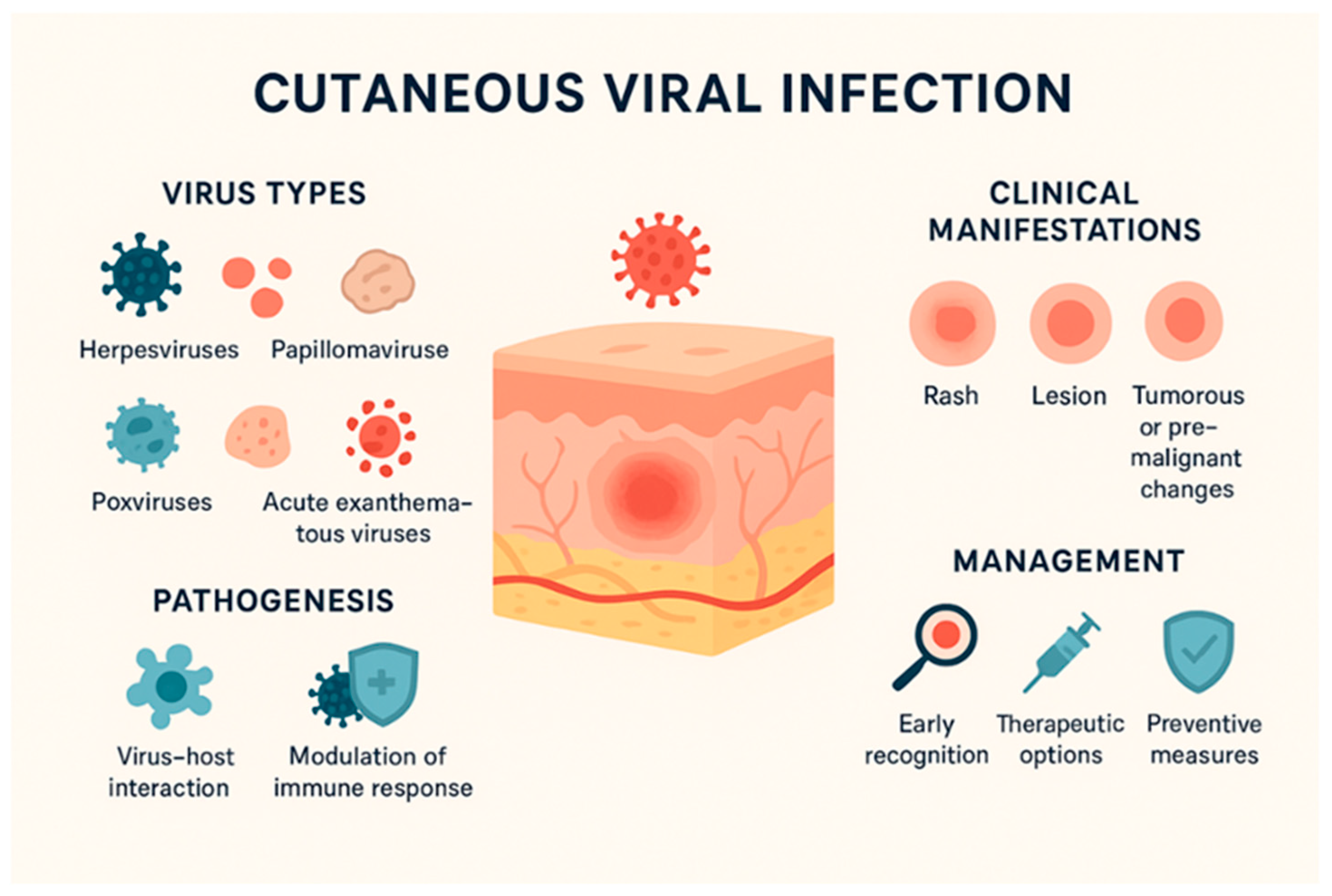

Cutaneous-Tropism Viruses: Unraveling Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Immunoprophylactic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

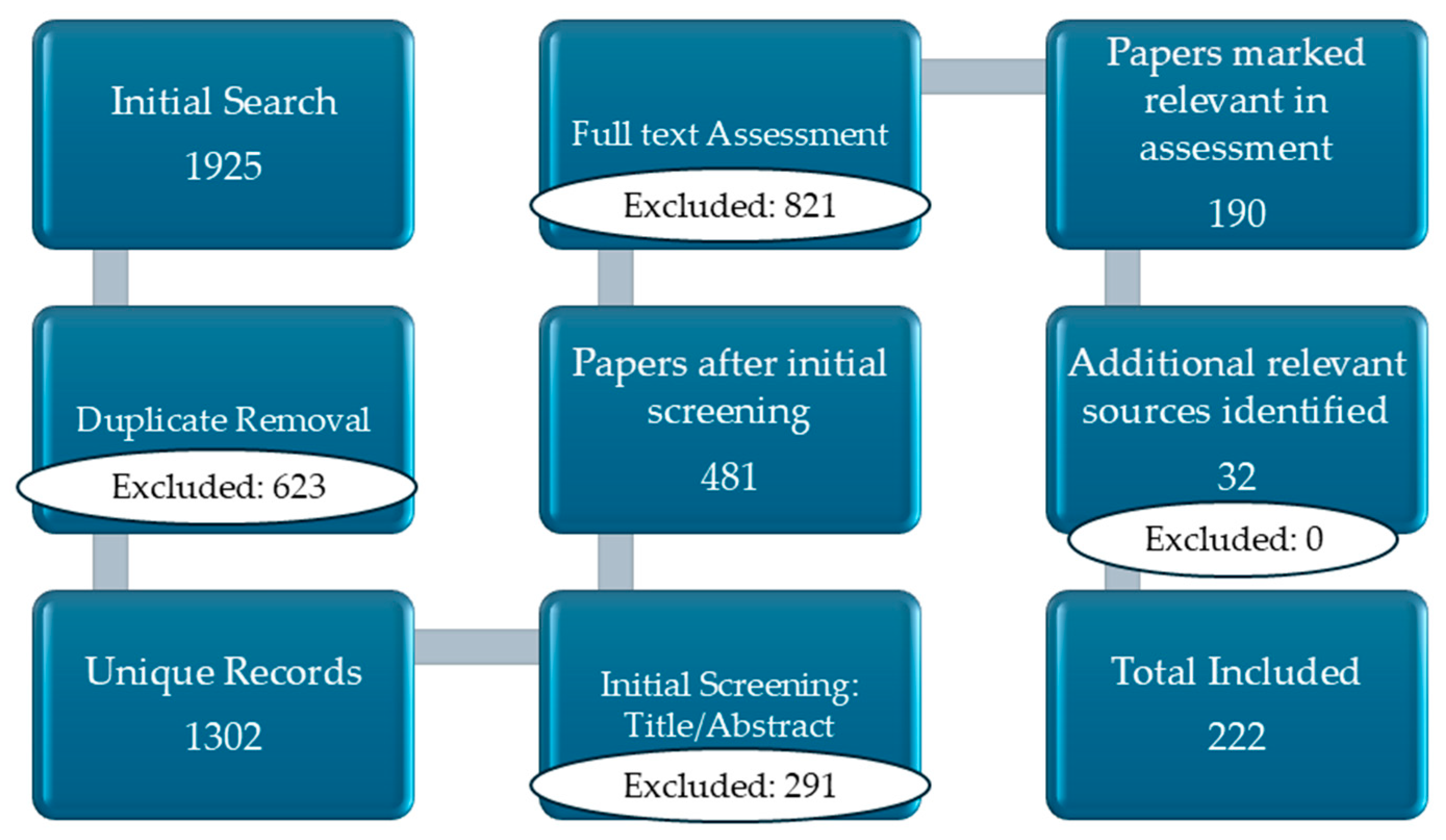

2. Materials

3. Skin Barriers and Viral Penetration Mechanisms

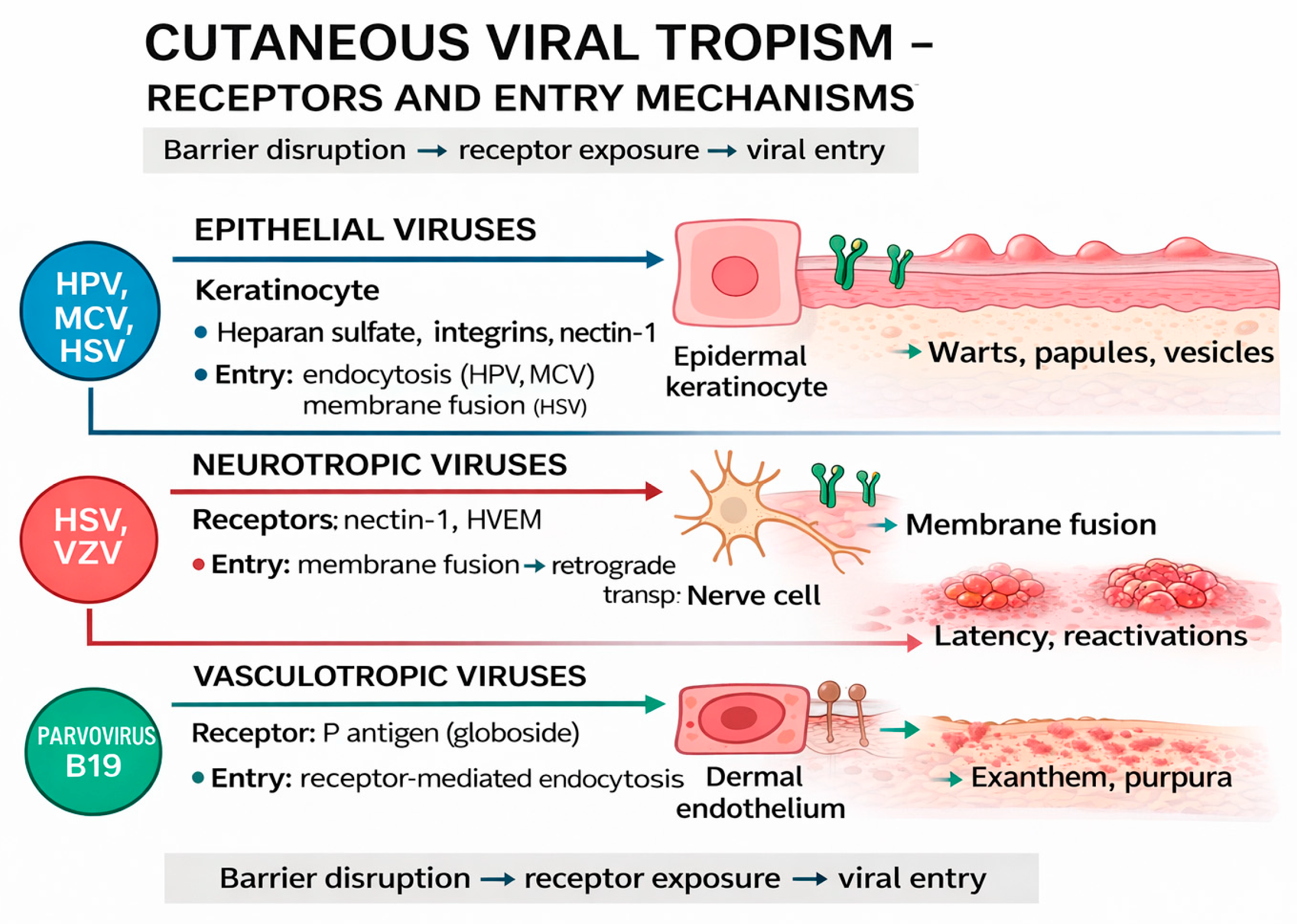

3.1. Viral Tropism for Epidermal and Dermal Cells

3.2. Viral Replication in Skin Cells

3.3. Local Immune Response of the Skin in Viral Infections

3.4. Cytopathic Effects and Immune Modulation by Viruses

4. Cutaneous Manifestations of DNA and RNA Viruses, Therapies, and Immunoprophylaxis

| Category | Virus | Virus Type | Cutaneous Manifestations | Treatment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papulo-vesicular lesions | HSV Herpes Simplex | DNA 1 | Grouped vesicles, ulcerations | Acyclovir, Valacyclovir, Isoprinosine’ Famciclovir | [69,70,71] |

| Papulo-vesicular lesions | VZV Varicella-Zoster Virus, | DNA | Typical vesicles, zoster | Acyclovir, Valacyclovir, Brivudin, Famciclovir | [72,73,74] |

| Papular lesions | MCV Molluscum Contagiosum Virus | DNA | Umbilicated papules | Curettage cryotherapy | [75,76] |

| Hyperplastic lesions | HPV Human Papilloma Virus, | DNA | Warts, dysplasia | Imiquimod, cryotherapy | [77,78] |

| Tumoral lesions | MCPyV Merkel cell polyomavirus | DNA | Merkel cell carcinoma | Surgery, immunotherapy | [79,80] |

| Vascular lesions | HHV-8 Human Herpesvirus | DNA | Kaposi sarcoma | ART (Antiretroviral Therapy) | [81,82] |

| Exanthems | Measles virus | RNA 2 | Maculopapular exanthem | Supportive | [83] |

| Exanthems | Rubella virus | RNA | Fine exanthem | Supportive | [84,85] |

| Chronic infections | HCV Hepatitis C virus | RNA | Lichen planus, PCT (Porphyria Cutanea Tarda) | DAAs (Direct-Acting Antivirals) | [86] |

| Papulo-vesicular lesions | Parvovirus B19 | DNA | Grouped vesicles, ulcerations | Acyclovir, Supportive | [87] |

4.1. DNA Viruses

4.1.1. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

4.1.2. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1/HSV-2)

4.1.3. Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

4.1.4. Molluscum Contagiosum Virus (MCV)

4.1.5. Polyomaviruses (HPyV): Merkel Cell Carcinoma

4.2. RNA Viruses

4.2.1. Measles Virus: Maculopapular Exanthemas

4.2.2. Rubella Virus: Rash and Lymphadenopathy

4.2.3. Parvovirus B19

4.2.4. Coxsackie Virus: Hand-Foot-Mouth Disease

4.2.5. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV): Associated Dermatological Manifestations

4.2.6. SARS-CoV-2 Virus

5. Future Directions and Current Limitations in Dermatovirology Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSV-1 | Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 |

| HPV | Human Papilloma Virus |

| MCV | Molluscum Contagiosum Virus |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| VZV | Varicella-Zoster Virus |

| ECM | The extracellular matrix |

| PRRs | pattern-recognition receptors |

| TLR | through Toll-like receptors |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ART | Antiretroviral Therapy |

| DAAs | Direct-Acting Antivirals |

| HPyV | Polyomaviruses |

| MCC | Merkel cell carcinoma |

| MCPyV | Merkel cell polyomavirus |

| LTAg-t | truncated large T antigen |

| sTAg | small T antigen |

| TCR-T | adoptive T-cell therapies |

| MMR | vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella) |

| IGIV | specific immunoglobulins |

| CRS | congenital rubella syndrome |

| IVIG | Intravenous immunoglobulin |

| CVA6 | Coxsackievirus A6 |

| HFMD | hand-foot-and-mouth disease |

| EV71 | Enteroviruses 71 |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ECDC | Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

References

- Bhadoria, P.; Gupta, G.; Agarwal, A. Viral Pandemics in the Past Two Decades: An Overview. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 2745–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, C.N.; Harvey, R.A.; Fisher, B.D. Microbiology; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Parija, S.C. Introduction to Viruses. In Textbook of Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 687–713. [Google Scholar]

- Florea, C. (Ed.) Bacteriologie şi Virusologie: Îndreptar de Lucrări Practice; a 2-a; Zigotto: Galaţi, Romania, 2010; 312p. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, K.; Gao, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, C.; Xiang, Q.; Lu, L.; Liu, H. Evolution of Virology: Science History through Milestones and Technological Advancements. Viruses 2024, 16, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licker, M.; Moldovan, R. Special Microbiology Course Vol. I Bacteriology; Victor Babeş: Timișoara, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease|Wageningen University and Research Library Catalog. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/titel/1654235 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Yadav, D.K.; Yadav, N.; Khurana, S.M.P. Vaccines: Present Status and Applications. In Animal Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 523–542. [Google Scholar]

- Megha, K.; Mohanan, P. Role of Immunoglobulin and Antibodies in Disease Management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, N.C.; Möckel, M.; Niehues, H.; Rübsam, M.; Malter, W.; Zinser, M.; Krummenacher, C.; Knebel-Mörsdorf, D. Ex Vivo Infection of Human Skin Models with Herpes Simplex Virus 1: Accessibility of the Receptor Nectin-1 during Formation or Impairment of Epidermal Barriers Is Restricted by Tight Junctions. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e00262-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.S.; Vukmanovic-Stejic, M. Skin Barrier Immunity and Ageing. Immunology 2020, 160, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Möckel, M.; De La Cruz, N.C.; Rübsam, M.; Wirtz, L.; Tantcheva-Poor, I.; Malter, W.; Zinser, M.; Bieber, T.; Knebel-Mörsdorf, D. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Can Bypass Impaired Epidermal Barriers upon Ex Vivo Infection of Skin from Atopic Dermatitis Patients. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00864-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, P.M.; Mentino, D.; De Marco, A.; Del Vecchio, C.; Garra, S.; Cazzato, G.; Foti, C.; Crovella, S.; Calamita, G. Aquaporins Are One of the Critical Factors in the Disruption of the Skin Barrier in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvathy, C.; Panicker, S.P.; Babu, A.M.; Rehana, K.; Aswani, A.; Thilakan, K. Unveiling the Symphony of Small Molecules in Cutaneous Harmony, Pathophysiology, Regeneration and Cancer. In Small Molecules for Cancer Treatment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 57–102. [Google Scholar]

- van der Krieken, D. Cutaneous Host-Microbiome Interactions: Functional Analyses and Interventions; Radboud University: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, C.L.; Elliott, G. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Enters Human Keratinocytes by a Nectin-1-Dependent, Rapid Plasma Membrane Fusion Pathway That Functions at Low Temperature. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10379–10389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlicki, C.M. Viral Diseases Affecting the Skin. Dermatol. Rev. 2024, 5, e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, H.; Truong, N.R.; Sirimanne, D.R.; Cunningham, A.L. Breaching the Barrier: Investigating Initial Herpes Simplex Viral Infection and Spread in Human Skin and Mucosa. Viruses 2024, 16, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knebel-Mörsdorf, D. Nectin-1 and HVEM: Cellular Receptors for HSV-1 in Skin. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thier, K.; Petermann, P.; Rahn, E.; Rothamel, D.; Bloch, W.; Knebel-Mörsdorf, D. Mechanical Barriers Restrict Invasion of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 into Human Oral Mucosa. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01295-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril, S.; Corchado-Cobos, R.; García-Sancha, N.; Revelles, L.; Revilla, D.; Ugalde, T.; Román-Curto, C.; Pérez-Losada, J.; Cañueto, J. Viruses and Skin Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, L.-I.; Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; McKerrow, J.H. Location, Location, Location: Five Facts about Tissue Tropism and Pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shome, A.; Mukherjee, G.; Shome, A. Applications of Deep Learning in Virology. In Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain in Precision Medicine and Virology; Chatterjee, J.M., Saxena, S.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Santacroce, L.; Magrone, T. Molluscum Contagiosum Virus: Biology and Immune Response. In Poxviruses; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Beber, A.A.C.; Benvegnú, A.M.; da Pieve, D.; Dallazem, L.N.D.; Neumaier, L.F.T. Viral Infections. In Dermatology in Public Health Environments: A Comprehensive Textbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 203–291. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-H.; He, B.; Singh, S.; Martin, N.P. Vector Tropism. In Vectorology for Optogenetics and Chemogenetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Doorbar, J. The Papillomavirus Life Cycle. J. Clin. Virol. 2005, 32, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, A.A.; Breuer, J.; Cohen, J.I.; Cohrs, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; Gilden, D.; Grose, C.; Hambleton, S.; Kennedy, P.G.; Oxman, M.N. Varicella Zoster Virus Infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.I. Herpesvirus Latency. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3361–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, C.; Breuer, J. The Biology of Varicella-Zoster Virus Replication in the Skin. Viruses 2022, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmer, F.P.; de Moura Guimarães, C.; Peixoto, A.B.; Pontes, K.F.M.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Tonni, G.; Araujo Júnior, E. Parvovirus B19 Infection and Pregnancy: Review of the Current Knowledge. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. Skin Infections. In Disease Causing Microbes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Guidry, J.; Scott, R. The Interaction between Human Papillomavirus and Other Viruses. Virus Res. 2017, 231, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.; Rovnak, J.; Badani, H.; Cohrs, R.J. A Comparison of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Varicella-Zoster Virus Latency and Reactivation. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1581–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvia, R.; Margheri, F.; Stincarelli, M.A.; Laurenzana, A.; Fibbi, G.; Gallinella, G.; Ferri, C.; Del Rosso, M.; Zakrzewska, K. Parvovirus B19 Activates in Vitro Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts: A Possible Implication in Skin Fibrosis and Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 3526–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadh, A.A. The Role of Cytosolic Lipid Droplets in Hepatitis C Virus Replication, Assembly, and Release. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 5156601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, C.J.; Howard, C.R.; Murphy, F.A. Virus Replication. In Fenner and White’s Medical Virology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, A.H.; Novick, P.J. Role of Rab GTPases in Membrane Traffic and Cell Physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, K.; Shaw, L.E.; Symmank, D.; Weninger, W. The Extracellular Matrix in Skin Inflammation and Infection. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 682414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Lee, D.-K.; Lee, C.-Y.; Park, S.-C.; Yang, J. Host Subcellular Organelles: Targets of Viral Manipulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etibor, T.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Amorim, M.J. Liquid Biomolecular Condensates and Viral Lifecycles: Review and Perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, M.; Weitzman, M.D. Replication Compartments of DNA Viruses in the Nucleus: Location, Location, Location. Viruses 2020, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinserling, V. Paramyxovirus and Other RNA Virus Infections. In Infectious Pathology of the Respiratory Tract; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Beirag, N.; Varghese, P.M.; Kishore, U. Innate Immune Response to Viral Infection. In Innate Immunity: Pattern Recognition and Effector Mechanisms; Kishore, U., George, A.J.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, T.C.A.B.; Criado, P.R.; Criado, R.F.J.; Trés, G.F.S.; Sotto, M.N. Update on Vasculitis: Overview and Relevant Dermatological Aspects for the Clinical and Histopathological Diagnosis—Part II. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorbar, J. Host Control of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 47, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harden, M.E.; Munger, K. Human Papillomavirus Molecular Biology. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2017, 772, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, A.; Saunders, R. Overview on the Management of Herpes Simplex Virus Infections: Current Therapies and Future Directions. Antivir. Res. 2025, 237, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.E. Measles Immunity and Immunosuppression. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 46, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, V.; Prezioso, C.; Moens, U. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, L.; Requena, C. Histopathology of the More Common Viral Skin Infections. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (Engl. Ed.) 2010, 101, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xia, L.; Tian, P.; Jiao, L.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, G. MHC-I Pathway Disruption by Viruses: Insights into Immune Evasion and Vaccine Design for Animals. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1540159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Lin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Cui, L. Decoding MHC Loss: Molecular Mechanisms and Implications for Immune Resistance in Cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golais, F.; Mrázová, V. Human Alpha and Beta Herpesviruses and Cancer: Passengers or Foes? Folia Microbiol. 2020, 65, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Stern, J.; Daley, S.F. Molluscum Contagiosum. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Louten, J. Virus Structure and Classification. Essent. Hum. Virol. 2016, 6, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wanat, K.A.; Perelygina, L.; Rosenbach, M.; Haun, P.L.; Drolet, B.A.; Shields, B.E. Cutaneous Granulomas Associated with Rubella Virus: A Clinical Review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, J.; Mangale, V.; Thienphrapa, W.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Feuer, R. Recent Progress in Understanding Coxsackievirus Replication, Dissemination, and Pathogenesis. Virology 2015, 484, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, M.; Harada, T.; Shimizu, T.; Hiroshige, J. Forchheimer Spots in Rubella. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prinzio, A.; Bastard, D.P.; Torre, A.C.; Mazzuoccolo, L.D. Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in Adults Caused by Coxsackievirus B1-B6. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2022, 97, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R. Advances and Perspectives in the Management of Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections. Molecules 2021, 26, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Amanullah, M.; Wang, X.; Liang, Q.; Hua, C.; Zhou, C.; Song, Y.; van der Veen, S.; Cheng, H. RNA Sequencing and Metabolic Analysis of Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis-like Mice with Chronic Restrain Stress. Life Sci. 2023, 326, 121788. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.I. Therapeutic Vaccines for Herpesviruses. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e179483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batisani, K. The Role of mRNA Vaccines in Infectious Diseases: A New Era of Immunization. Trop. Dis. Travel. Med. Vaccines 2025, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, L.; Zhong, J.; Gao, X. Advancing mRNA Vaccines for Infectious Diseases: Key Components, Innovations, and Clinical Progress. Essays Biochem. 2025, 69, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.; Hagan, T.; Rouphael, N.; Wu, S.-Y.; Xie, X.; Kazmin, D.; Wimmers, F.; Gupta, S.; van der Most, R.; Coccia, M.; et al. System Vaccinology Analysis of Predictors and Mechanisms of Antibody Response Durability to Multiple Vaccines in Humans. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Friedman, H.M. An mRNA Vaccine to Prevent Genital Herpes. Transl. Res. 2022, 242, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Jarrahian, C.; Zehrung, D.; Mitragotri, S.; Prausnitz, M. Delivery Systems for Intradermal Vaccination. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011, 351, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłysik, K.; Pietraszek, A.; Karewicz, A.; Nowakowska, M. Acyclovir in the Treatment of Herpes Viruses–A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 4118–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Marinelli, G.; Trilli, I.; Sardano, R.; Pezzolla, C.; Inchingolo, F.; Palermo, A.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D. Topical and Systemic Therapeutic Approaches in the Treatment of Oral Herpes Simplex Virus Infection: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sherees, H.A.A.; Al-khateeb, S.N.A.; Al-Muhannak, F.H.N. Immunological Activities of Isoprinosine Inhibition on Viral Infections in Human. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2019, 16, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Guo, F.; Tang, S. Brivudine for Treatment of Varicella-Zoster Virus Encephalitis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 162, 108206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.; Chen, E.; Thevathasan, A.; Yan, T.; Moso, M.; Sasadeusz, J.; Muhi, S. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Varicella Zoster Virus Central Nervous System Infection in an Australian Tertiary Hospital. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan Abed, Z. A Comprehensive Review of Acyclovir: Synthesis, Antiviral Mechanism, Modifications, and Innovative Analytical Techniques in Pharmaceutical Applications. Chem. Rev. Lett. 2025, 8, 967–980. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrych, J.M.; Krupa, J.; Malinowski, M.; Krasowski, M.; Kalinowska, A.; Pietras, W.; Kozieł, A.; Kurek, Z.; Jentkiewicz, A.; Obeid, E.H. Molluscum Contagiosum: A Comprehensive Review of Treatment Modalities. Wiadomości Lek. 2025, 2025, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Romero, R.; Navarrete-Dechent, C.; Downey, C. Molluscum Contagiosum: An Update and Review of New Perspectives in Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borella, F.; Gallio, N.; Mangherini, L.; Cassoni, P.; Bertero, L.; Benedetto, C.; Preti, M. Recent Advances in Treating Female Genital Human Papillomavirus Related Neoplasms with Topical Imiquimod. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowska, J.; Markowska, A.; Jach, R.; Michałak, M.; Gryboś, A. The Effect of Cryotherapy and Local Pharmacological Treatment on Eradication of Highly Oncogenic HPV and Lesions on the Cervix. Clin. Surg. 2021, 6, 3377. [Google Scholar]

- Loke, A.S.; Lambert, P.F.; Spurgeon, M.E. Current in Vitro and in Vivo Models to Study MCPyV-Associated MCC. Viruses 2022, 14, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagase, K.; Narisawa, Y. Immunotherapy for Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, O.S.; McDade, H.; Tinney, F.J., Jr.; Weeks-Groh, S.R.; Lurain, K. HHV-8-associated Diseases in Transplantation: A Case Report and Narrative Review Focused on Diagnosis and Prevention. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2024, 26, e14334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, D.; Iida, S.; Hirota, K.; Ueji, T.; Matsumura, T.; Nishida, Y.; Uehira, T.; Katano, H.; Shirasaka, T. Evaluation of Human Herpesvirus-8 Viremia and Antibody Positivity in Patients with HIV Infection with Human Herpesvirus-8-related Diseases. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engeland, C.E.; Ungerechts, G. Measles Virus as an Oncolytic Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.K.; Moss, W.J. Rubella. Lancet 2022, 399, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, W.; Butt, A.; Akhtar, N.; Rafiq, M.; Gohar, M.; Idrees, Z.; Ahmad, N. Developing Computationally Efficient Optimal Control Strategies to Eradicate Rubella Disease. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 035202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.M.; Manaresi, E.; Vischini, G.; Provenzano, M.; Corradetti, V.; Giannella, M.; Bonazzetti, C.; Rinaldi, M.; Fabbrizio, B.; Ravaioli, M. Exploring Parvovirus B19 Pathogenesis and Therapy among Kidney Transplant Recipients: Case Report and Review of Literature. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e360–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.-S.; Moon, J.; Byun, J.-I.; Sunwoo, J.-S.; Lim, J.-A.; Lee, S.-T.; Jung, K.-H.; Park, K.-I.; Jung, K.-Y.; Kim, M. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment Outcomes of Parvovirus B19 Encephalitis in Immunocompetent Adults. J. NeuroVirol. 2017, 23, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohto, U.; Shibata, T.; Tanji, H.; Ishida, H.; Krayukhina, E.; Uchiyama, S.; Miyake, K.; Shimizu, T. Structural Basis of CpG and Inhibitory DNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptor 9. Nature 2015, 520, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, A.A. Human Papillomaviruses: Diversity, Infection and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, N.S.; de Carvalho da Silva, R.J.; do Val, I.C.; Bazzo, M.L.; da Silveira, M.F. Brazilian Protocol for Sexually Transmitted Infections 2020: Human Papillomavirus (Hpv) Infection. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2021, 54, e2020790. [Google Scholar]

- Plotzker, R.E.; Vaidya, A.; Pokharel, U.; Stier, E.A. Sexually Transmitted Human Papillomavirus: Update in Epidemiology, Prevention, and Management. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2023, 37, 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Branisteanu, D.E.; Pintilie, A.; Dumitriu, A.; Cerbu, A.; Ciobanu, D.; Oanta, A.; Tatu, A. Clinical, Laboratory and Therapeutic Profile of Lichen Planus. Med.-Surg. J. 2017, 121, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tatu, A.L.; Nwabudike, L.C. Reply to: Kubiak K et al. Endosymbiosis and Its Significance in Dermatology. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, e346–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Pavia, G.; Ciccozzi, A.; Quirino, A.; Marascio, N.; Gigliotti, S.; Matera, G.; Romano, C.; Locci, C.; Azzena, I.; et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions in Global Immunization Strategies. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoi, C.L.; Cristea, O.M.; Vulcanescu, D.D.; Voinescu, A.; Dragomir, T.L.; Sima, L.V.; Tanasescu, S.; Harich, O.O.; Balasoiu, A.T.; Iliescu, D.G.; et al. Seroprevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Types 1 and 2 among Pregnant Women in South-Western Romania. Life 2024, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Dawn, A.; Das, A. HPV Vaccines—An Overview. Indian J. Dermatol. 2025, 70, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, I.; Ilic, M. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage Estimates Among the Primary Target Cohort (9–14-Year-Old Girls) in the World (2010–2024). Vaccines 2025, 13, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Ploner, A.; Astorga Alsina, A.M.; Deng, Y.; Ask Schollin, L.; Lei, J. Effectiveness of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination against High-Grade Cervical Lesions by Age and Doses: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2025, 49, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, A.R.; Watson-Jones, D.; Kim, J.J.; Dull, P. Single-Dose Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: An Update. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2024, 2024, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fappani, C.; Bianchi, S.; Panatto, D.; Petrelli, F.; Colzani, D.; Scuri, S.; Gori, M.; Amendola, A.; Grappasonni, I.; Tanzi, E. HPV Type-Specific Prevalence a Decade after the Implementation of the Vaccination Program: Results from a Pilot Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, S.; Mimba, B.-R.; Akunne, O. Eliminating Cervical Cancer: The Impact of Screening and Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2025, 22, E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska, B.; Rudnicka, L. HPV Infections—Classification, Pathogenesis, and Potential New Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuind, A.E.; Balaji, K.A.; Du, A.; Yuan, Y.; Dull, P. Human Papillomavirus Prophylactic Vaccines: Update on New Vaccine Development and Implications for Single-Dose Policy. JNCI Monogr. 2024, 2024, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccarese, G.; Herzum, A.; Serviddio, G.; Occella, C.; Parodi, A.; Drago, F. Efficacy of Human Papillomavirus Vaccines for Recalcitrant Anogenital and Oral Warts. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghiar, L.; Sandor, M.; Sachelarie, L.; Bodog, R.; Huniadi, A. Skin Lesions Caused by HPV—A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaiqy, M.; MacLure, K. A Systematic Review of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Challenges and Strategies to Enhance Uptake. Vaccines 2024, 12, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekanmbi, V.; Guo, F.; Hsu, C.D.; Shan, Y.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Berenson, A.B. Incomplete HPV Vaccination among Individuals Aged 27–45 Years in the United States: A Mixed-Effect Analysis of Individual and Contextual Factors. Vaccines 2023, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dus-Ilnicka, I.; Rybińska, A.; Rusiecka, A.; Weigle, A.; McKay-Chopin, S.; Radwan-Oczko, M.; Gheit, T. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus DNA in the Saliva of Patients with Oral Lichen Planus. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, S.; Singh, P.; Joshi, T.; Aftab, M.; Firdausi, N.; Khan, A.; Mishra, N.; Jamil Khan, N.; Tanwar, P.; Gupta, V.; et al. Human Papillomavirus-Mediated Cervical Cancer: Epigenetic Interplay and Clinical Implications. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1633283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, F.; Alromaihi, R.A.; Kumar, V.; Anwar, S. Cancer Vaccines: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Progress, and Combination Immunotherapies with a Focus on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.E.; Becker, G.L.; Jackson, J.B.; Rysavy, M.B. Human Papillomavirus and Associated Cancers: A Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Clavijo, A.; Martí-Martí, I.; Ferrándiz-Pulido, C.; Verdaguer-Faja, J.; Jaka, A.; Toll, A. Human Papillomavirus-Related Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, P.C.; Leib, D.A. Neurons Versus Herpes Simplex Virus: The Innate Immune Interactions That Contribute to a Host–Pathogen Standoff. Future Virol. 2015, 10, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, L.; Weßollek, K.; Peeters, T.B.; Yazdi, A.S. Infections with Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 1327–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagens-Rotman, K.; Przybylska, R.; Gerke, K.; Adamski, Z.; Czarnecka-Operacz, M. Genital Herpes as Still Significant Dermatological, Gynaecological and Venereological Problem. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpes Simplex Virus. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Overview: Genital Herpes. In InformedHealth.org [Internet]; Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG): Cologne, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.Y.; Balch, C.; Oh, H.S. Toward the Eradication of Herpes Simplex Virus: Vaccination and Beyond. Viruses 2024, 16, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashkina, S.N.; Budanova, E.V. Current treatments for herpes: From traditional antiviral therapy to vaccines and genetic engineering (review). Russ. J. Ski. Vener. Dis. 2025, 28, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madavaraju, K.; Koganti, R.; Volety, I.; Yadavalli, T.; Shukla, D. Herpes Simplex Virus Cell Entry Mechanisms: An Update. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 617578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Sah, R.; Ahsan, O.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Insights into the Novel Therapeutics and Vaccines against Herpes Simplex Virus. Vaccines 2023, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, L.; Xie, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. Mucosal Immune Response in Biology, Disease Prevention and Treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.T.S. Mechanistic Perspectives on Herpes Simplex Virus Inhibition by Phenolic Acids and Tannins: Interference with the Herpesvirus Life Cycle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sharma, S.; Akojwar, N.; Dondulkar, A.; Yenorkar, N.; Pandita, D.; Prasad, S.K.; Dhobi, M. An Insight into Current Treatment Strategies, Their Limitations, and Ongoing Developments in Vaccine Technologies against Herpes Simplex Infections. Vaccines 2023, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiutiuca, C.; Dinu, C.; Alexa, I.A.; Pruna, R.; Luca, M.C.; Dorobat, C.; Vata, A.; Lupoae, M. Neurological Complications of Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection. Rev. Chim. 2016, 67, 995–997. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, A.; Goldust, M.; Wollina, U. Herpes Zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses 2022, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, K.; Marin, M.; Gershon, A.A. Clinical Manifestations of Varicella: Disease Is Largely Forgotten, but It’s Not Gone. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, S380–S384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Hersh, A.L.; Jones, T.W. Clinical Progress Note: Varicella Zoster. J. Hosp. Med. 2025, 20, 1348–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Kim, S.; Kwon, J.; Jung, K.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Varicella-Zoster Virus-Specific Cell-Mediated Immune Response Kinetics and Latent Viral Load Depending on Aging. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingles (Herpes Zoster). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/shingles-(herpes-zoster) (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Ji, Y.; Liao, H. Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection and Varicella-Zoster Virus Vaccine-Related Ocular Complications. Vaccines 2025, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszko, M.; Zapolnik, P.; Kmiecik, W.; Czajka, H. Herpes Zoster: Risk Factors for Occurrence, Complications, and Recurrence with a Focus on Immunocompromised Patients. Diseases 2025, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, A.A.; Gershon, M.D.; Shapiro, E.D. Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine: Prevention of Varicella and of Zoster. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, S387–S397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaire-Bermal, N.; Jia, N.; Maronilla, M.A.C.; Lopez, J.F.; Zeng, G.; Wu, W.; Nimo, A.B.C.; Luan, C.; Xin, Q. Immunogenicity and Safety of a Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine in Healthy Children Aged 12 to 15 Months: A Phase III, Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Clinical Trial. Vaccines 2025, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiavarini, M.; Bechini, A.; Boccalini, S.; Barash, A.; Castellana, E.; Senape, A.; Bonanni, P. Vaccination Against Herpes Zoster in Adults: Current Strategies in European Union Countries. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira Gomes, J.; Gagliardi, A.M.; Andriolo, B.N.; Torloni, M.R.; Andriolo, R.B.; dos Santos Puga, M.E.; Canteiro Cruz, E. Vaccines for Preventing Herpes Zoster in Older Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD008858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, C.; Anselem, O.; Caseris, M.; Lachâtre, M.; Tazi, A.; Driessen, M.; Pinquier, D.; Le Cœur, C.; Saunier, A.; Bergamelli, M.; et al. Prevention and Management of VZV Infection during Pregnancy and the Perinatal Period. Infect. Dis. Now 2024, 54, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, H.; Chemaly, R.F. Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin (Human) (VARIZIG) in Immunocompromised Patients: A Subgroup Analysis for Safety and Outcomes from a Large, Expanded-Access Program. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, A.K.; Harder, B.C.; Schlichtenbrede, F.C.; Jarczok, M.N.; Tesarz, J. Valacyclovir versus Acyclovir for the Treatment of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus in Immunocompetent Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD011503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.; Mogensen, T.; Cohrs, R. Recent Issues in Varicella-Zoster Virus Latency. Viruses 2021, 13, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, C.; Davila, P.V.; Cole, E.; Karnsakul, W. Varicella and Zoster Vaccination Strategies in Immunosuppressed Pediatric Transplant Recipients. Vaccines 2025, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronkwright, D.; Cohen, J. Microwave Therapy as a Novel, Safe, and Effective Treatment for Children and Adults with Molluscum Contagiosum. Ski. J. Cutan. Med. 2026, 10, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Smythe, C.; Yousefian, F.; Berman, B. Molluscum Contagiosum Virus Evasion of Immune Surveillance: A Review. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achdiat, P.A.; Andiani, S.; Hindritiani, R.; Gondokaryono, S.P.; Nuzuliyah, G.; Usman, H.A.; Maharani, R.H. Molluscum Contagiosum in HIV Patient Treated with 20% Topical Glycolic Acid After Resistance with Topical Tretinoin. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Melewska, K. Poxviruses in Children. In Poxviruses; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaeyi, S.A.; Bozio, C.H.; Duffy, J.; Rubin, L.G.; Hariri, S.; Stephens, D.S.; MacNeil, J.R. Meningococcal Vaccination: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2020, 69, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D.E. and FDA Approves First Treatment for Molluscum Contagiosum. FDA. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-first-treatment-molluscum-contagiosum (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Wells, A.; Saikaly, S.K.; Schoch, J.J. Intralesional Immunotherapy for Molluscum Contagiosum: A Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Cidofovir for the Treatment of Molluscum Contagiosum Virus. Viruses 2022, 14, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacarrubba, F.; Micali, G.; Trecarichi, A.C.; Quattrocchi, E.; Monfrecola, G.; Verzì, A.E. New Developing Treatments for Molluscum Contagiosum. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbat, E.; Al-Niaimi, F.; Ali, F.R. Molluscum Contagiosum: Review and Update on Management. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2017, 34, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, G.; Townsend, S.; Jahnke, M.N. Molluscum Contagiosum: Review and Update on Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, Risk, Prevention, and Treatment. Curr. Derm. Rep. 2020, 9, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Barratt, J.; Coemans, E.; Dayananda, P.; Del Riccio, M.; Fulop, T.; Gabutti, G.; Gravenstein, S.; Hiligsmann, M.; Hummers, E.; et al. Infectious Diseases, Infection Control, Vaccines and Long-Term Care: An European Interdisciplinary Council on Ageing Consensus Document. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 38, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, M.A.; Imlay, H. Polyomaviruses After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Viruses 2025, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini, S.; Messina, S.; Moens, U.; Pietropaolo, V. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus (MCPyV) and Its Possible Role in Head and Neck Cancers. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, B.; Broseghini, E.; Ricci, C.; Corti, B.; Viola, C.; Misciali, C.; Baraldi, C.; Vaccari, S.; Lambertini, M.; Venturi, F.; et al. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: An Updated Review Focused on Bone and Bone Marrow Metastases. Cancers 2025, 17, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadendorf, D.; Lebbé, C.; zur Hausen, A.; Avril, M.-F.; Hariharan, S.; Bharmal, M.; Becker, J.C. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Epidemiology, Prognosis, Therapy and Unmet Medical Needs. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 71, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soikkeli, A.I.; Kyläniemi, M.K.; Sihto, H.; Alinikula, J. Oncogenic Merkel Cell Polyomavirus T Antigen Truncating Mutations Are Mediated by APOBEC3 Activity in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passerini, S.; Prezioso, C.; Babini, G.; Ferlosio, A.; Cosio, T.; Campione, E.; Moens, U.; Ciotti, M.; Pietropaolo, V. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus (MCPyV) DNA and Transcripts in Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC). Pathogens 2023, 12, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenin, K.R.; Tieche, I.S.; Di Benedetto, C.E.; Schrager, M.; Dye, K.N. The Small Tumor Antigen of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Accomplishes Cellular Transformation by Uniquely Localizing to the Nucleus despite the Absence of a Known Nuclear Localization Signal. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Milewski, D.; Coxon, A.; Gelb, T.; Garman, K.A.; Porch, J.; Khanna, A.; Collado, L.; Hill, N.T.; Daily, K.; et al. Interlocking Host and Viral Cis-Regulatory Networks Drive Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e188924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodig, S.J.; Cheng, J.; Wardzala, J.; DoRosario, A.; Scanlon, J.J.; Laga, A.C.; Martinez-Fernandez, A.; Barletta, J.A.; Bellizzi, A.M.; Sadasivam, S.; et al. Improved Detection Suggests All Merkel Cell Carcinomas Harbor Merkel Polyomavirus. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4645–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.; Yee, C. Polyomavirus-Positive Merkel Cell Carcinoma: The Beginning of the Beginning. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e179749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, L.; Hippe, D.S.; Park, S.Y.; Fu, A.; Akaike, T.; Lachance, K.; Cahill, K.; Doolittle-Amieva, C.; Nghiem, P. Polyomavirus Antibodies for Merkel Cell Carcinoma Recurrence Detection. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.M.; Shalhout, S.Z.; Wright, K.M.; Miller, M.A.; Kaufman, H.L.; Emerick, K.S.; Reeder, H.T.; Silk, A.W.; Thakuria, M. The Prognostic Value of the Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Serum Antibody Test: A Dual Institutional Observational Study. Cancer 2024, 130, 2670–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.F.; You, J. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Associated Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 13, 200232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojnica, A.; Ljuca, K.; Akhtar, S.; Gatalica, Z.; Vranic, S. An Updated Review of the Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, E.P. The Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Retroviral Infection. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danova, I. A Review of Measles Virus. Probl. Infect. Parasit. Dis. 2021, 49, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, S.; Ahuja, R. Drug-Induced vs. Viral Maculopapular Exanthem—Resolving the Dilemma. Dermatopathology 2022, 9, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misin, A.; Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Campisciano, G.; Zanotta, N.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Comar, M.; Luzzati, R. Measles: An Overview of a Re-Emerging Disease in Children and Immunocompromised Patients. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawson, A.R.; Croft, A.M. Rubella Virus Infection, the Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and the Link to Autism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bîrluțiu, V.; Bîrluțiu, R.-M. Measles—Clinical and Biological Manifestations in Adult Patients, Including a Focus on the Hepatic Involvement: Results from a Single-Center Observational Cohort Study from Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, L.I.; Haralambieva, I.H.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Goergen, K.M.; Grill, D.E.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Gene Expression Factors Associated with Rubella-Specific Humoral Immunity After a Third MMR Vaccine Dose. Viruses 2025, 17, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turaiche, M.; Feciche, B.; Gluhovschi, A.; Bratosin, F.; Bogdan, I.; Bota, A.V.; Grigoras, M.L.; Gurban, C.V.; Cerbu, B.; Toma, A.-O.; et al. Biological Profile and Clinical Features as Determinants for Prolonged Hospitalization in Adult Patients with Measles: A Monocentric Study in Western Romania. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Aulakh, R. Measles-Associated CNS Complications: A Review. J. Child Sci. 2022, 12, e172–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasadyn, F.; Mamo, N.; Caplan, A. Battling Measles: Shifting Strategies to Meet Emerging Challenges and Inequities. Ethics Med. Public Health 2025, 33, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.; Strebel, P.; Orenstein, W.; Icenogle, J.; Poland, G.A. Rubella. Lancet 2015, 385, 2297–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toizumi, M.; Vo, H.M.; Dang, D.A.; Moriuchi, H.; Yoshida, L.-M. Clinical Manifestations of Congenital Rubella Syndrome: A Review of Our Experience in Vietnam. Vaccine 2019, 37, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikole, K.M.; Kamble, H.V.; Waghmare, S.A. A Comprehensive Review on Rubella Virus: Review Article. J. Pharma Insights Res. 2024, 2, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, G.; Retallack, H.; Kim, C.N.; Wang, A.; Shin, D.; DeRisi, J.L.; Nowakowski, T. Rubella Virus Tropism and Single-Cell Responses in Human Primary Tissue and Microglia-Containing Organoids. eLife 2023, 12, RP87696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, A.F.; Parasiliti, M.; Franco, R.; Gallitelli, V.; Perelli, F.; Spanò, A.; Pallone, B.; Serafini, M.G.; Signore, F.; Eleftheriou, G.; et al. Successful Elimination of Endemic Rubella in the WHO European Region. Is It Proper to Remove the Recommendation for Preconceptional Immunization? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, L.C.; Rugna, M.M.; Durães, T.A.; Pereira, S.S.; Callado, G.Y.; Pires, P.; Traina, E.; Araujo Júnior, E.; Granese, R. Congenital Rubella Syndrome in the Post-Elimination Era: Why Vigilance Remains Essential. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banko, A.; Cirkovic, A.; Petrovic, V.; Ristic, M.; Vukovic, V.; Stankovic-Djordjevic, D.; Miljanovic, D. Seroprevalence of Measles-, Mumps-, and Rubella-Specific Antibodies in Future Healthcare Workers in Serbia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2025, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantey, J.B. Parvovirus. In Neonatal Infections: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management; Cantey, J.B., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Pudasaini, P.; Das, K.; Gorai, S.; Paudel, S.; G.c., S.; Adhikari, S.; Thapa, B.; Kurien, A.J. Parvovirus in Dermatology: A Review. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2023, 2, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Hoopmann, M.; Geipel, A.; Sonek, J.; Enders, M. Prenatal Parvovirus B19 Infection. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2024, 310, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquot, R.; Gerfaud-Valentin, M.; Mekki, Y.; Billaud, G.; Jamilloux, Y.; Sève, P. Infection de l’adulte à Parvovirus. Rev. Méd. Intern. 2022, 43, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Chen, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Xia, H.; Chen, L.; Feng, H.; Feng, L. Multisystem Involvement Induced by Human Parvovirus B19 Infection in a Non-Immunosuppressed Adult: A Case Report. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 808205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heegaard, E.D.; Brown, K.E. Human Parvovirus B19. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algwaiz, G.; Alharbi, A.; Alsehaim, K.; Alahmari, A.; El Fakih, R.; Aljurf, M. Hematologic Manifestations of Parvovirus B19 Infection. Hematol./Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2023, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, S.; Cocchi, E.; Mambelli, L.; Radice, C.; Marchetti, F. Parvovirus B19 Infection in Children: A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmis, B.D.; Downing, C.; Tyring, S. Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease Caused by Coxsackievirus A6 on the Rise. Cutis 2018, 102, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joyce, A.M.; Hill, J.D.; Tsoleridis, T.; Astbury, S.; Berry, L.; Howson-Wells, H.C.; Allen, N.; Canning, B.; Jones, C.B.; Clark, G.; et al. Coxsackievirus A6 U.K. Genetic and Clinical Epidemiology Pre- and Post-SARS-CoV-2 Emergence. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Saito, M.; Castro, P.T.; Traina, E.; Werner, H.; Elito Júnior, J.; Araujo Júnior, E. Coxsackievirus Group B Infections during Pregnancy: An Updated Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, K.; Martinetti, G.; Lucchini, R.; Kaya, G.; Mainetti, C. Coxsackievirus A6 and Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease:Three Case Reports of FamilialChild-to-Immunocompetent Adult Transmission and a Literature Review. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2013, 5, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.-J.; Kim, Y.-I.; Kim, S.-Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Suh, B.; Yu, J.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Jung, E.; et al. A Bivalent Inactivated Vaccine Prevents Enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus A16 Infections in the Mongolian Gerbil. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Xie, Y.; Ji, F.; Zhao, F.; Song, X.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Geng, J.; Yang, H.; Long, J.; et al. Effectiveness of EV-A71 Vaccine and Its Impact on the Incidence of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ji, W.; Chen, S.; Duan, G.; Jin, Y. Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease Challenges and Its Antiviral Therapeutics. Vaccines 2023, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, S.; Cheng, Y.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Rogier van Doorn, H.; Hafy, Z.; Kawichai, S.; Liu, C.-C.; Nam, N.T.; Ooi, M.H.; et al. Workshop on Use of Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease in Southeast Asia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, e140992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.S.; Tavares, F.N.; Sousa, I.P. Global Landscape of Coxsackieviruses in Human Health. Virus Res. 2024, 344, 199367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, A.A.S.; Ignat, M.D.; Barbu, R.E.; Dumitru, C.; Radaschin, D.S.; Bulza, V.; Mateescu Costin, S.A.; Pleșea-Condratovici, C.; Baroiu, L. Impact of Direct-Acting Antivirals on Extrahepatic Manifestations in Chronic Hepatitis C: A Narrative Review with a Hermeneutic Approach. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toska, E.; Minars, C.; Riskin, S.I. Skin Manifestations Among Individuals with Hepatitis C Infection. Cureus 2025, 17, e82902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayiner, M.; Golabi, P.; Farhat, F.; Younossi, Z.M. Dermatologic Manifestations of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Clin. Liver Dis. 2017, 21, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stasio, D.; Guida, A.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Marrone, A.; Fiori, F.; Lucchese, A. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection: Pathogenesis, Oral Manifestations, and the Role of Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.-H.; Tai, Y.-H.; Dai, Y.-X.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chen, T.-J.; Chen, M.-H. Association between Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Subsequent Chronic Inflammatory Skin Disease. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 1884–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskan Bermudez, N.; Rodríguez-Tamez, G.; Perez, S.; Tosti, A. Onychomycosis: Old and New. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Saravanan, S.; Vignesh, R.; Sivamalar, S.; Nallusamy, D.; Sankar, S.; Krithika, C.; Sridhar, C.; Raju, S.; Velu, V.; et al. Discovery of HCV Vaccine: Where Do We Stand? Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 57, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, D.; Lucchese, A.; Romano, A.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Serpico, R.; Marrone, A. The Clinical Impact of Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment on Patients Affected by Hepatitis C Virus-Related Oral Lichen Planus: A Cohort Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5409–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Coronel-Castillo, C.E.; Ramírez-Mejía, M.M. Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection, Extrahepatic Disease and the Impact of New Direct-Acting Antivirals. Pathogens 2024, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, L.; Cannova, S.; Ferrigno, E.; Landro, G.; Nonni, R.; Mantia, C.L.; Cartabellotta, F.; Calvaruso, V.; Di Marco, V. A Comprehensive Review of Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C: The Long Journey from Interferon to Pan-Genotypic Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs). Viruses 2025, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatu, A.L.; Nadasdy, T.; Bujoreanu, F.C. Familial Clustering of COVID-19 Skin Manifestations. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Sanchez-Flores, X.; Yau, J.; Huang, J.T. Cutaneous Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Battista, T. COVID-19 and Cutaneous Manifestations: A Review of the Published Literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviariza, A.; Budiani, L.M. Dermatologic Manifestation of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Res. 2021, 7, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembhre, M.K.; Parihar, A.S.; Sharma, V.K.; Imran, S.; Bhari, N.; Lakshmy, R.; Bhalla, A. Enhanced Expression of Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2 in Psoriatic Skin and Its Upregulation in Keratinocytes by Interferon-γ: Implication of Inflammatory Milieu in Skin Tropism of SARS-CoV-2. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Mi, Z.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F. High Expression of ACE2 on Keratinocytes Reveals Skin as a Potential Target for SARS-CoV-2. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 206-209.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seebacher, N.; Kirkham, J.; Smith, S.D. Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19: Diagnosis and Management. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 217, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Bshabshe, A.; Mousa, W.F.; Nor El-Dein, N. An Overview of Clinical Manifestations of Dermatological Disorders in Intensive Care Units: What Should Intensivists Be Aware Of? Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martora, F.; Battista, T.; Ruggiero, A.; Scalvenzi, M.; Villani, A.; Megna, M.; Potestio, L. The Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Inflammatory Skin Disorders and Other Cutaneous Diseases: A Review of the Published Literature. Viruses 2023, 15, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshgaran, G.; Dubin, D.P.; Gould, D.J. Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakou, A.I.; Routsi, E.; Plisioti, K.; Tziona, E.; Koumaki, D.; Kalamata, M.; Bompou, E.-K.; Sokou, R.; Ioannou, P.; Bonovas, S.; et al. Autoimmune Skin Diseases in the Era of COVID-19: Pathophysiological Insights and Clinical Implications. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lupoae, M.; Elisei, A.M.; Iacob, A.; Lupoae, A.; Tatu, A.L.; Niculeț, E.; Căuș, M.N.; Batîr, D.; Nechita, A.; Matei, M.N.; et al. Cutaneous-Tropism Viruses: Unraveling Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Immunoprophylactic Strategies. Life 2026, 16, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010174

Lupoae M, Elisei AM, Iacob A, Lupoae A, Tatu AL, Niculeț E, Căuș MN, Batîr D, Nechita A, Matei MN, et al. Cutaneous-Tropism Viruses: Unraveling Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Immunoprophylactic Strategies. Life. 2026; 16(1):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010174

Chicago/Turabian StyleLupoae, Mariana, Alina Mihaela Elisei, Ancuța Iacob, Andreea Lupoae, Alin Laurențiu Tatu, Elena Niculeț, Maria Nina Căuș, Denisa Batîr, Aurel Nechita, Mădălina Nicoleta Matei, and et al. 2026. "Cutaneous-Tropism Viruses: Unraveling Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Immunoprophylactic Strategies" Life 16, no. 1: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010174

APA StyleLupoae, M., Elisei, A. M., Iacob, A., Lupoae, A., Tatu, A. L., Niculeț, E., Căuș, M. N., Batîr, D., Nechita, A., Matei, M. N., Ștefan, C. S., Lisă, E. L., Irinel, L., & Tutunaru, D. (2026). Cutaneous-Tropism Viruses: Unraveling Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Immunoprophylactic Strategies. Life, 16(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010174