Enhancement of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy via the HIF-1apha/BNIP3 Pathway Promotes Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation of Aged Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Cellular Senescence Model

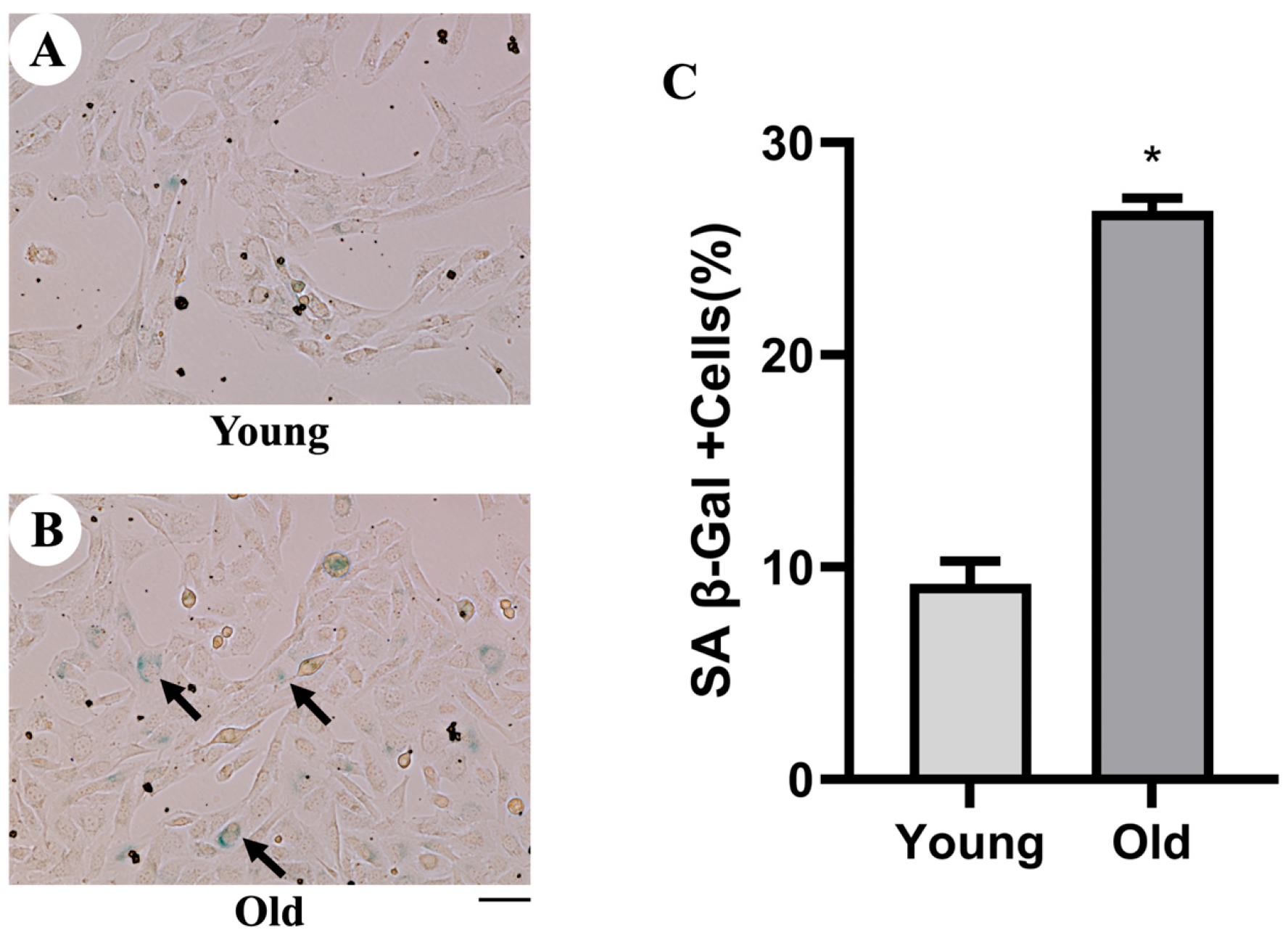

2.3. Assessment of Cellular Senescence

2.4. Autophagy Inhibitor Treatment

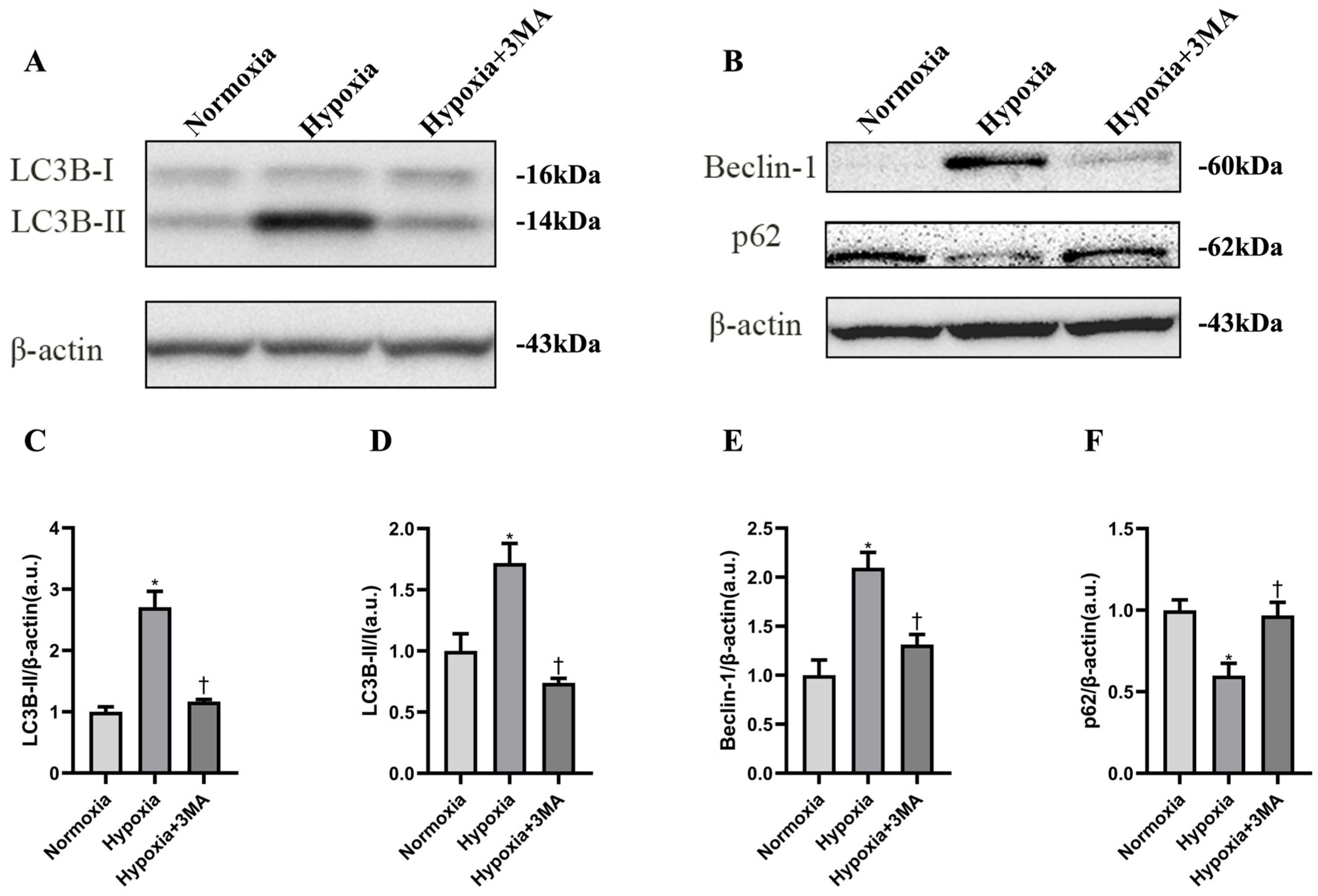

2.5. Western Blot

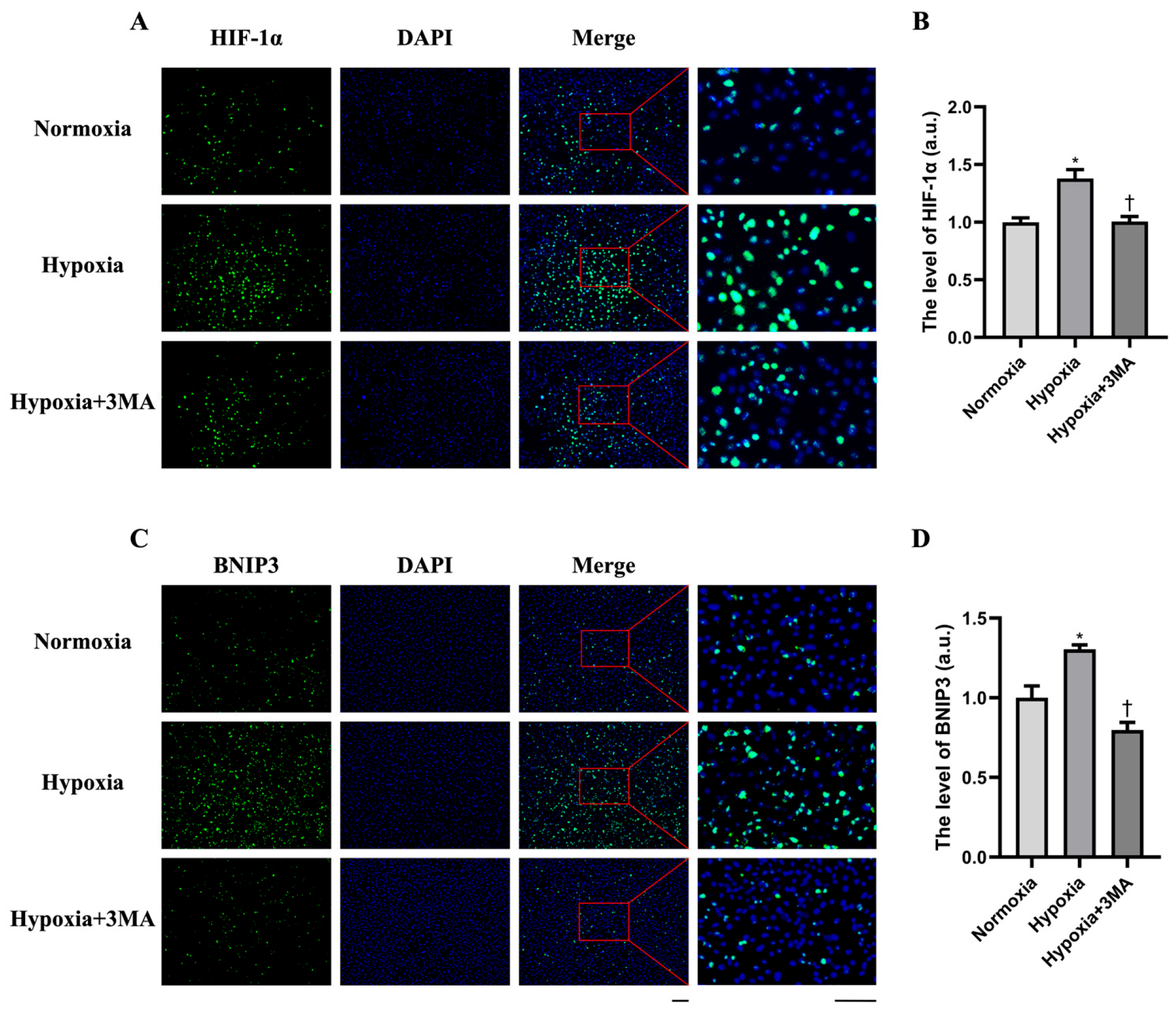

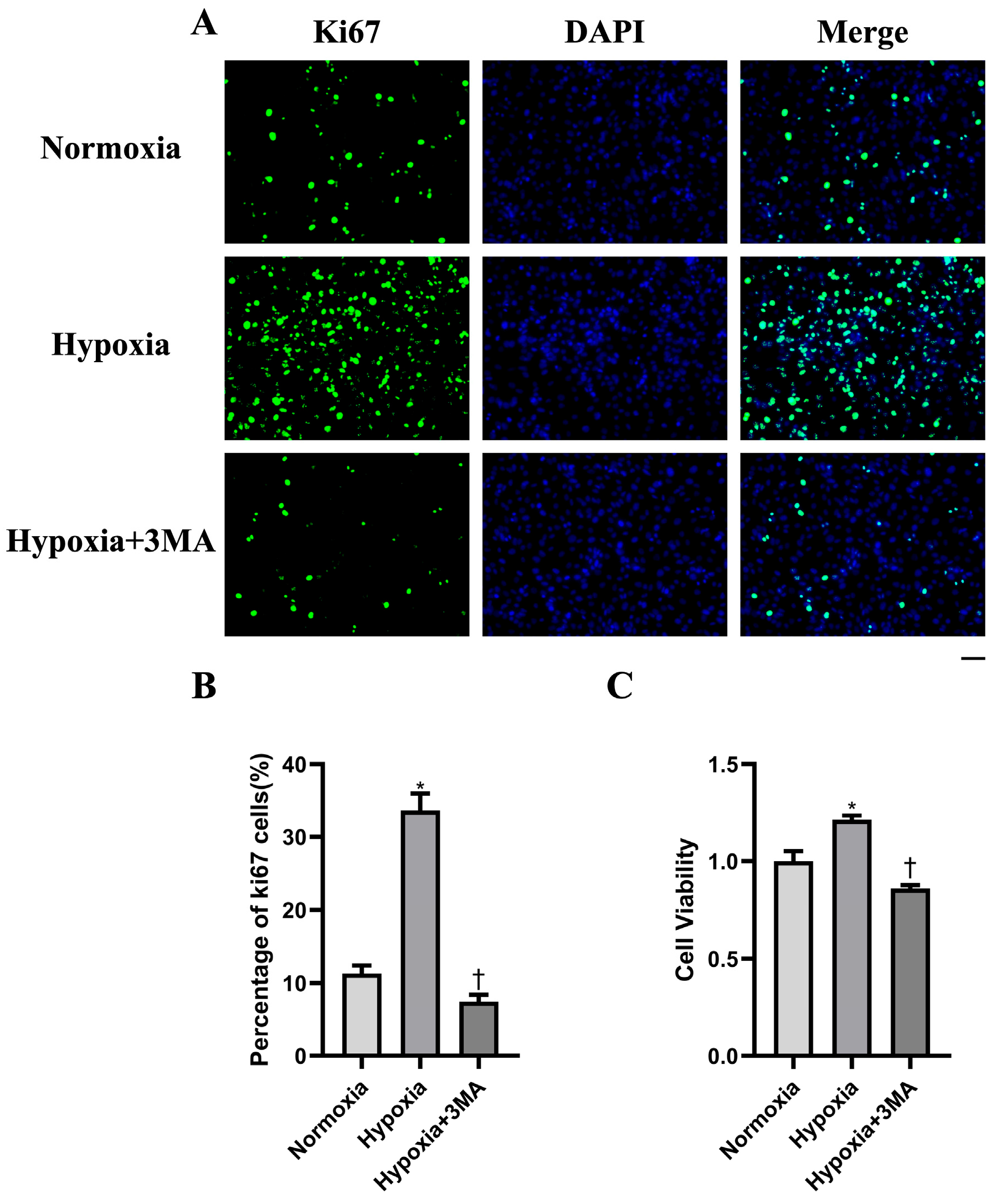

2.6. Immunofluorescence

2.7. Cell Counting Kit-8

2.8. Wound-Healing Assay

2.9. Myogenic Differentiation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Detection of Cellular Senescence by SA-β-Gal

3.2. HIF-1α and BNIP3 Expression by Immunofluorescence

3.3. Autophagy-Related Proteins

3.4. Cell Proliferation by Immunofluorescence and CCK-8

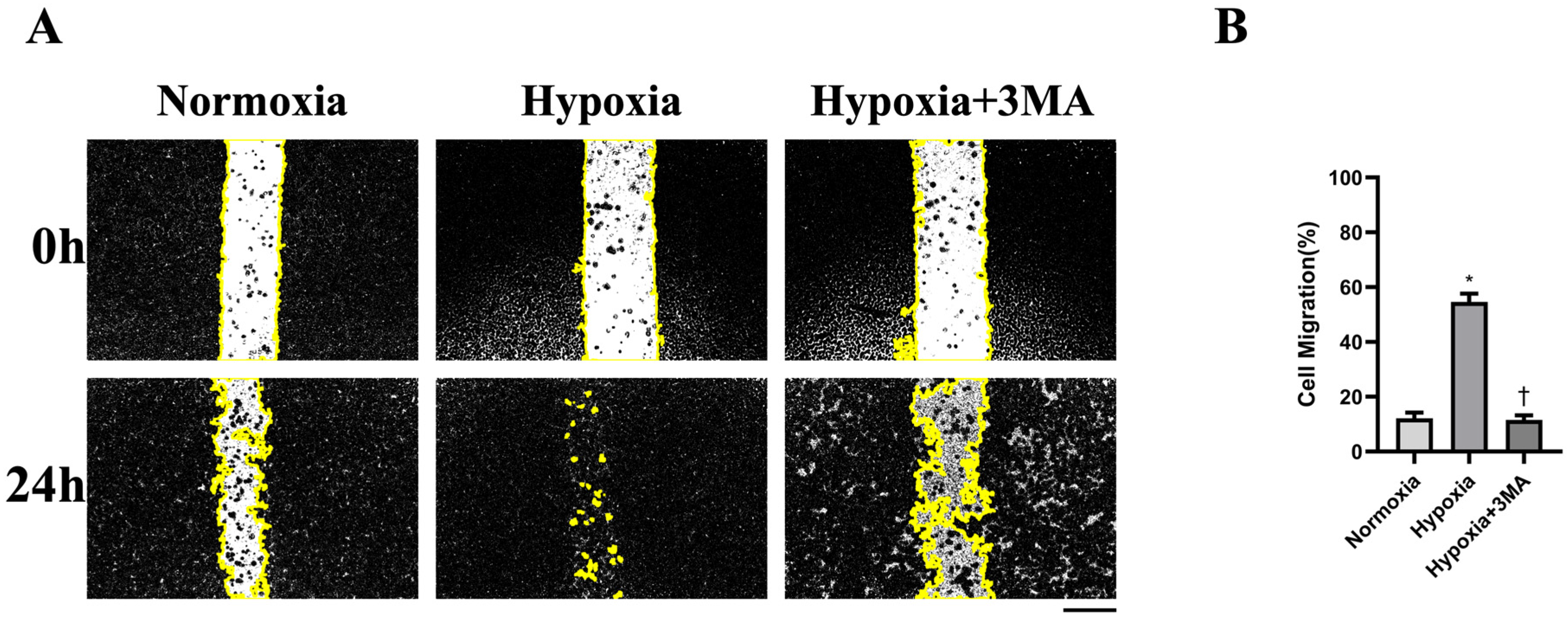

3.5. Cell Migration by Scratch-Wound Assay

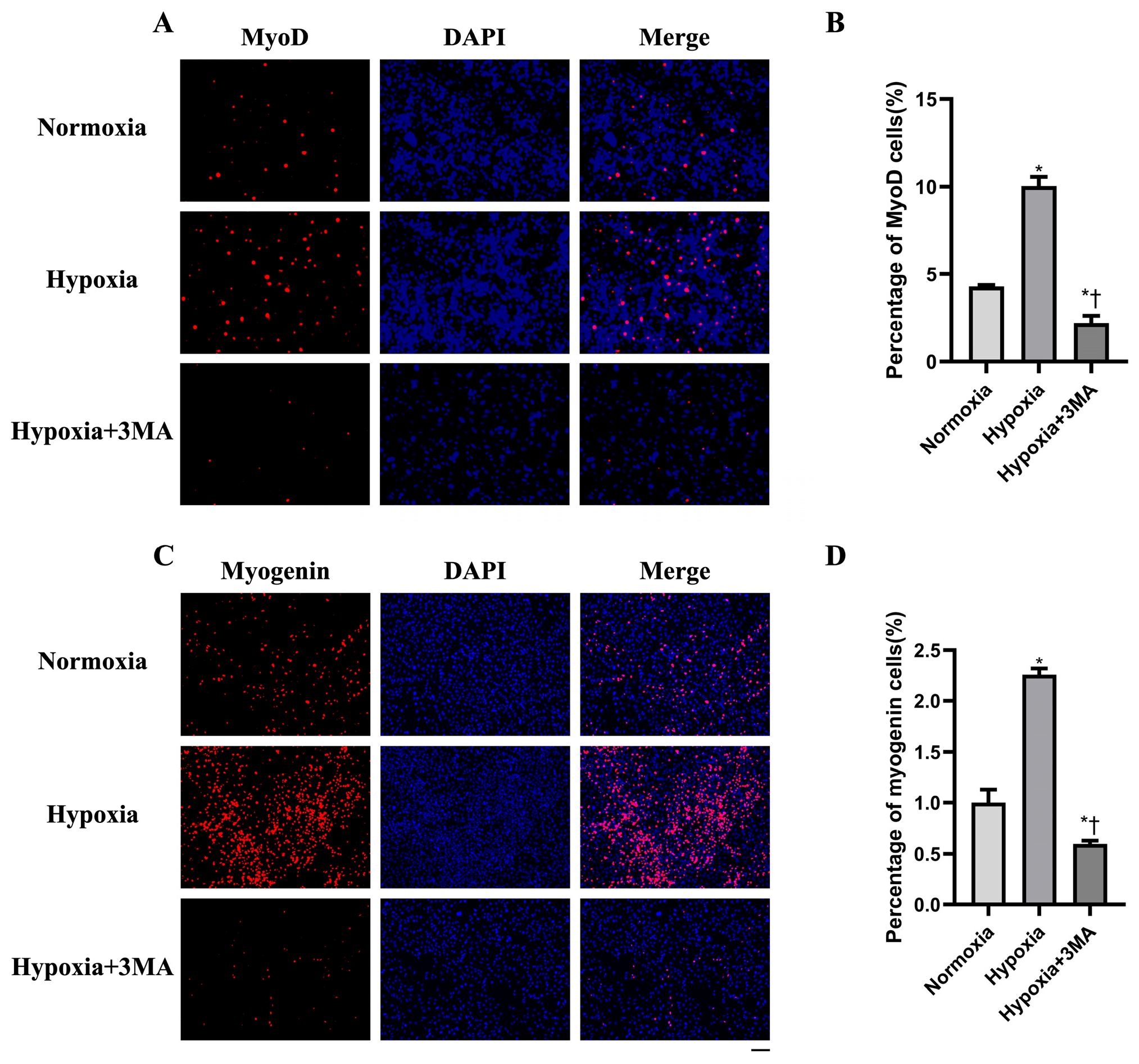

3.6. Myogenic Differentiation by Immunofluorescence

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MuSCs | skeletal muscle satellite cells |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| P/S | penicillin–streptomycin |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| SA-β-gal | senescence-associated β-galactosidase |

| 3-MA | 3-methyladenine |

| SDS–PAGE | SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 |

| BNIP3 | Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 |

| MyoD | myogenic differentiation 1 |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| WB | Western blotting |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| SEM | standard error of the mean |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| Ki67 | proliferation marker protein Ki-67 |

| LC3B | microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta |

References

- Sousa-Victor, P.; Gutarra, S.; García-Prat, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Ortet, L.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Jardí, M.; Ballestar, E.; González, S.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature 2014, 506, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Victor, P.; García-Prat, L.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Control of satellite cell function in muscle regeneration and its disruption in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonewald, L. Use it or lose it to age: A review of bone and muscle communication. Bone 2019, 120, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castets, P.; Frank, S.; Sinnreich, M.; Rüegg, M.A. “Get the Balance Right”: Pathological Significance of Autophagy Perturbation in Neuromuscular Disorders. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2016, 3, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campanario, S.; Ramírez-Pardo, I.; Hong, X.; Isern, J.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Assessing Autophagy in Muscle Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 620409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takahashi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Mohamed, J.S.; Gotoh, T.; Pereira, S.L.; Alway, S.E. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases autophagy signaling in resting and unloaded plantaris muscles but selectively suppresses autophagy protein abundance in reloaded muscles of aged rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 92, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguilera, M.O.; Delgui, L.R.; Romano, P.S.; Colombo, M.I. Chronic Infections: A Possible Scenario for Autophagy and Senescence Cross-Talk. Cells 2018, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galasso, L.; Cappella, A.; Mulè, A.; Castelli, L.; Ciorciari, A.; Stacchiotti, A.; Montaruli, A. Polyamines and Physical Activity in Musculoskeletal Diseases: A Potential Therapeutic Challenge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, J.; Ding, P.; Wu, H.; Yang, P.; Guo, H.; Tian, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhao, Q. Sarcopenia: Molecular regulatory network for loss of muscle mass and function. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1037200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, S.S.; Seo, Y.K.; Kwon, K.S. Sarcopenia targeting with autophagy mechanism by exercise. BMB Rep. 2019, 52, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Biological Functions of Autophagy Genes: A Disease Perspective. Cell 2019, 176, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manganelli, V.; Matarrese, P.; Antonioli, M.; Gambardella, L.; Vescovo, T.; Gretzmeier, C.; Longo, A.; Capozzi, A.; Recalchi, S.; Riitano, G.; et al. Raft-like lipid microdomains drive autophagy initiation via AMBRA1-ERLIN1 molecular association within MAMs. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2528–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, C.; Liang, J.; Ren, Y.; Huang, J.; Jin, B.; Wang, G.; Chen, N. A Preclinical Systematic Review of the Effects of Chronic Exercise on Autophagy-Related Proteins in Aging Skeletal Muscle. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 930185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, C.W.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Xiong, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Dong, X.C.; Yin, X.M. Pharmacological promotion of autophagy alleviates steatosis and injury in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver conditions in mice. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kraig, E.; Linehan, L.A.; Liang, H.; Romo, T.Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Benavides, A.D.; Curiel, T.J.; Javors, M.A.; Musi, N.; et al. A randomized control trial to establish the feasibility and safety of rapamycin treatment in an older human cohort: Immunological, physical performance, and cognitive effects. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 105, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rivera-Torres, S.; Fahey, T.D.; Rivera, M.A. Adherence to Exercise Programs in Older Adults: Informative Report. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 5, 2333721418823604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Colleluori, G.; Villareal, D.T. Aging, obesity, sarcopenia and the effect of diet and exercise intervention. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 155, 111561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, R.; Jiang, T.; She, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Shen, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, S. Effects of Cobalt Chloride, a Hypoxia-Mimetic Agent, on Autophagy and Atrophy in Skeletal C2C12 Myotubes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7097580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bellot, G.; Garcia-Medina, R.; Gounon, P.; Chiche, J.; Roux, D.; Pouysségur, J.; Mazure, N.M. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 29, 2570–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, J.; Gong, S.H.; He, Y.L.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, G.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhao, M.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Y.Z.; et al. Autophagy Is Essential for Neural Stem Cell Proliferation Promoted by Hypoxia. Stem Cells 2023, 41, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lian, B.; Ma, L.; Zhao, J. Autophagy induced by hypoxia in pulpitis is mediated by HIF-1α/BNIP3. Arch. Oral Biol. 2024, 159, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khor, S.C.; Razak, A.M.; Wan Ngah, W.Z.; Mohd Yusof, Y.A.; Abdul Karim, N.; Makpol, S. The Tocotrienol-Rich Fraction Is Superior to Tocopherol in Promoting Myogenic Differentiation in the Prevention of Replicative Senescence of Myoblasts. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xie, L.; Yin, A.; Nichenko, A.S.; Beedle, A.M.; Call, J.A.; Yin, H. Transient HIF2A inhibition promotes satellite cell proliferation and muscle regeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2339–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pircher, T.; Wackerhage, H.; Aszodi, A.; Kammerlander, C.; Böcker, W.; Saller, M.M. Hypoxic Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Maintenance and Regeneration: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 684899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Behnke, B.J.; Delp, M.D.; Dougherty, P.J.; Musch, T.I.; Poole, D.C. Effects of aging on microvascular oxygen pressures in rat skeletal muscle. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2005, 146, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Prat, L.; Martínez-Vicente, M.; Perdiguero, E.; Ortet, L.; Rodríguez-Ubreva, J.; Rebollo, E.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Gutarra, S.; Ballestar, E.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 2016, 529, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, F.; Mangiavini, L.; La Rocca, P.; Piccoli, M.; Ghiroldi, A.; Rota, P.; Tarantino, A.; Canciani, B.; Coviello, S.; Messina, C.; et al. Human Sarcopenic Myoblasts Can Be Rescued by Pharmacological Reactivation of HIF-1α. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, W.; Wen, Y.; Bi, P.; Lai, X.; Liu, X.S.; Liu, X.; Kuang, S. Hypoxia promotes satellite cell self-renewal and enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation. Development 2012, 139, 2857–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo, R.; Wu, Z.; Liu, A.; Li, Q.; Han, T.; Shen, C. Hypoxic preconditioning-engineered bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote muscle satellite cell activation and skeletal muscle regeneration via the miR-210-3p/KLF7 mechanism. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbandian, M.; Radak, Z.; Takeda, M. Lactate Metabolism and Satellite Cell Fate. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 610983, Erratum in: Front Physiol. 2022, 12, 817264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy is a key factor in maintaining the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells by promoting quiescence and preventing senescence. Autophagy 2016, 12, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Catarinella, G.; Bracaglia, A.; Skafida, E.; Procopio, P.; Ruggieri, V.; Parisi, C.; De Bardi, M.; Borsellino, G.; Madaro, L.; Puri, P.L.; et al. STAT3 inhibition recovers regeneration of aged muscles by restoring autophagy in muscle stem cells. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202302503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, S.; Ahn, B. Filbertone Reduces Senescence in C2C12 Myotubes Treated with Doxorubicin or H2O2 through MuRF1 and Myogenin. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noguchi, M.; Kitakaze, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Mukai, K.; Harada, N.; Yamaji, R. β-Cryptoxanthin Improves p62 Accumulation and Muscle Atrophy in the Soleus Muscle of Senescence-Accelerated Mouse-Prone 1 Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, H.; Zhang, P.; Xie, R.; Cui, W. HIF-1α/BNIP3 signaling pathway-induced-autophagy plays protective role during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 120, 109464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Feng, C.; Lin, J.; Geng, M.; Qu, D.; Xing, J.; Lin, H.; Ma, X.; Nakanishi, R.; Maeshige, N.; et al. Enhancement of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy via the HIF-1apha/BNIP3 Pathway Promotes Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation of Aged Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Life 2026, 16, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010144

Zhou L, Feng C, Lin J, Geng M, Qu D, Xing J, Lin H, Ma X, Nakanishi R, Maeshige N, et al. Enhancement of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy via the HIF-1apha/BNIP3 Pathway Promotes Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation of Aged Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Life. 2026; 16(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Li, Chenghao Feng, Jinrun Lin, Minghao Geng, Danni Qu, Jihao Xing, Hao Lin, Xiaoqi Ma, Ryosuke Nakanishi, Noriaki Maeshige, and et al. 2026. "Enhancement of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy via the HIF-1apha/BNIP3 Pathway Promotes Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation of Aged Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells" Life 16, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010144

APA StyleZhou, L., Feng, C., Lin, J., Geng, M., Qu, D., Xing, J., Lin, H., Ma, X., Nakanishi, R., Maeshige, N., Kondo, H., & Fujino, H. (2026). Enhancement of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy via the HIF-1apha/BNIP3 Pathway Promotes Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation of Aged Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Life, 16(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010144