The Effects of FemmeBalance Supplement on Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Four-Cycle Single-Arm Observational Study of a Novel Nutritional Supplement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Dermatologist Grading

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients

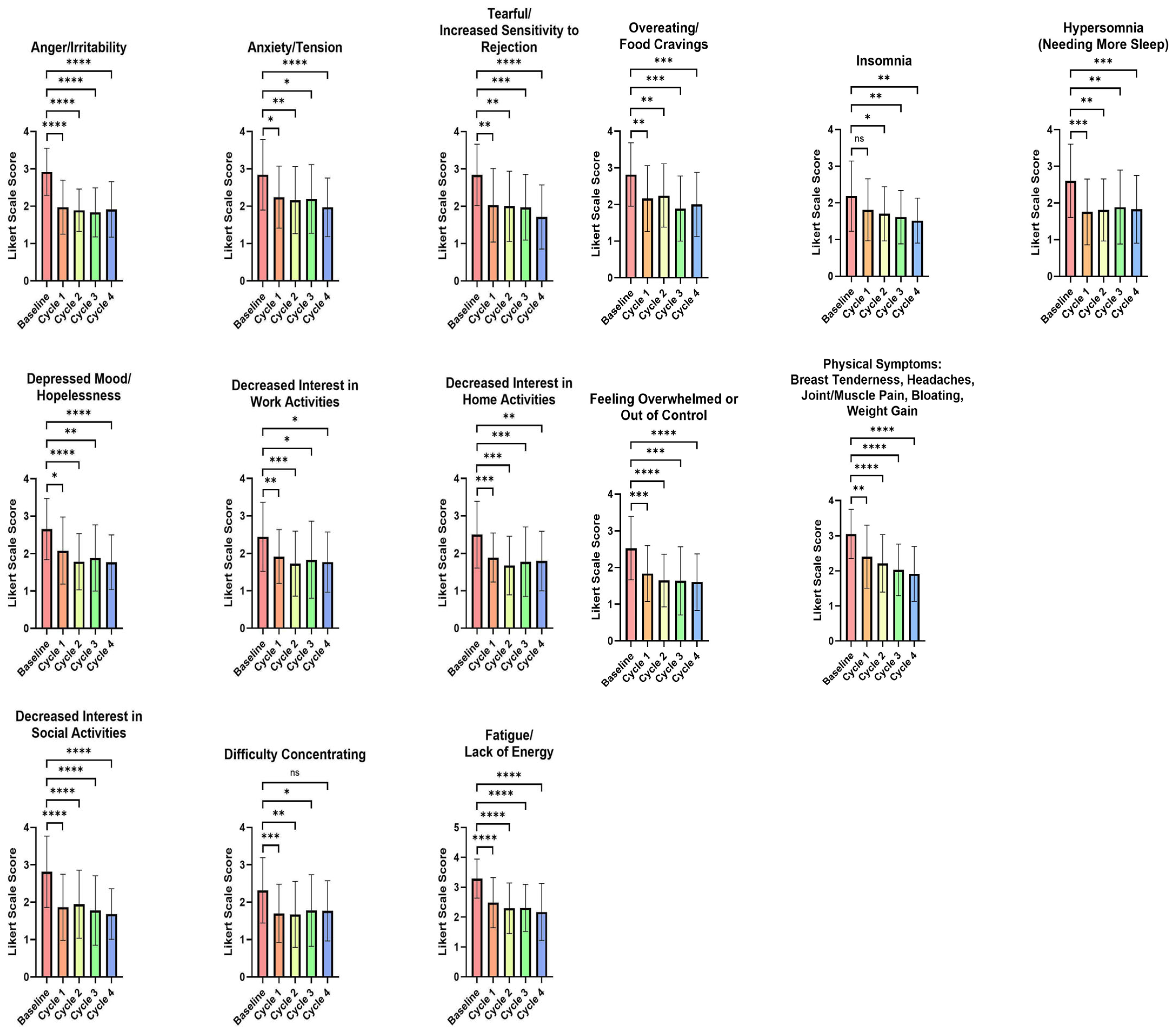

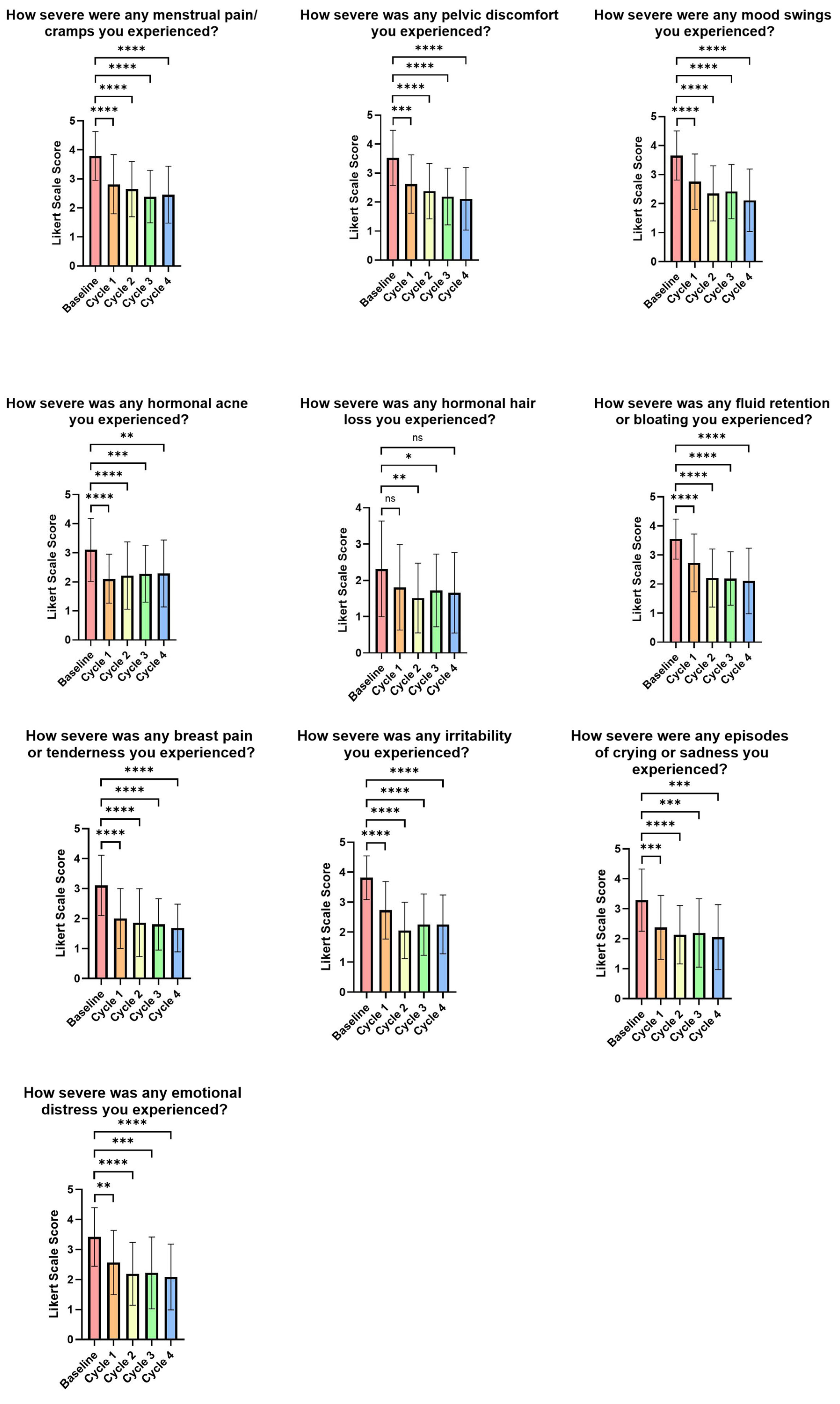

3.2. Impact of the Test FemmeBalance Supplement on Premenstrual Symptoms Evaluated by the PSST Questionnaire

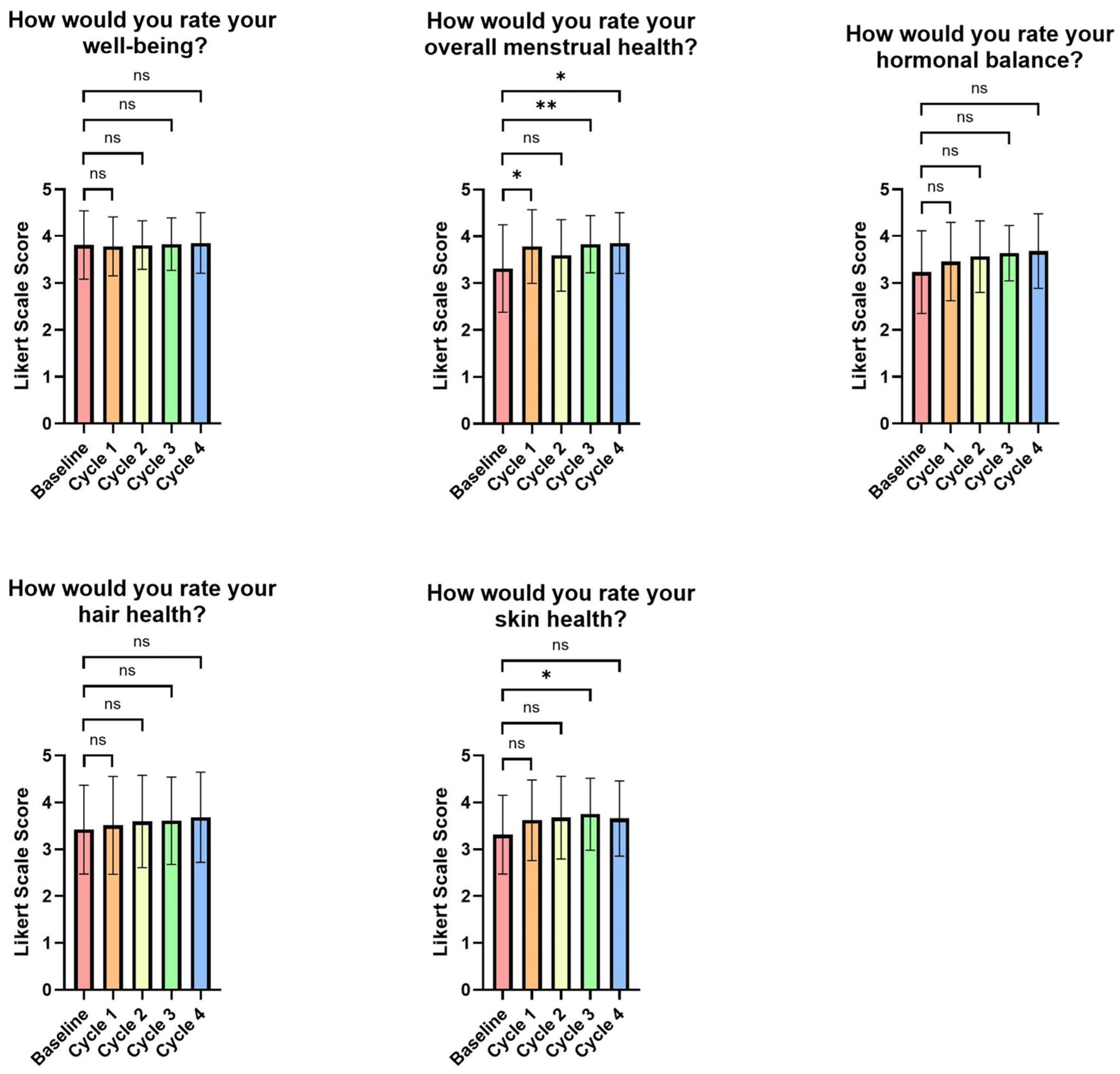

3.3. Impact of the FemmeBalance Supplement on PMS Symptoms Evaluated by Study-Specific Questionnaires

3.4. Impact of the FemmeBalance Supplement on Expert Skin Grading

3.5. Participants’ Perception of the FemmeBalance Supplement and Its Impact on Relieving PMS Symptoms

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schoep, M.E.; Nieboer, T.E.; van der Zanden, M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Nap, A.W. The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: A survey among 42,879 women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 569.e1–569.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Global, regional, and national burden of premenstrual syndrome, 1990–2019: An analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Antonio, C.; Santano-Mogena, E.; Cordovilla-Guardia, S. Dysmenorrhea, Premenstrual Syndrome, and Lifestyle Habits in Young University Students in Spain, A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Res. JNR 2025, 33, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of Premenstrual Disorders: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 7. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#1526774088 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Epperson, C.N.; Steiner, M.; Hartlage, S.A.; Eriksson, E.; Schmidt, P.J.; Jones, I.; Yonkers, K.A. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, T.; Steiner, M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Burden of illness and treatment update. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008, 33, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J. International PCOS Network. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modzelewski, S.; Oracz, A.; Żukow, X.; Iłendo, K.; Śledzikowka, Z.; Waszkiewicz, N. Premenstrual syndrome: New insights into etiology and review of treatment methods. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1363875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.R.; Jones, J.B.; Aperi, J.; Shemtov, R.; Karne, A.; Borenstein, J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 111, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, J.; Brown, J.; O’Brien, P.M.; Wyatt, K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD001396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkers, K.A.; Brown, C.; Pearlstein, T.B.; Foegh, M.; Sampson-Landers, C.; Rapkin, A. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheed, B.; Kuiper, J.H.; Uthman, O.A.; O’Mahony, F.; O’Brien, P.M.S. Non-contraceptive oestrogen-containing preparations for controlling symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD010503. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Faro, V.; Johansson, T.; Johansson, Å. The risk of venous thromboembolism in oral contraceptive users: The role of genetic factors—A prospective cohort study of 240,000 women in the UK Biobank. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, e1–e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaei, H.; Khayat, S.; Kasaeian, A.; Javadimehr, M. Effect of curcumin on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in women with premenstrual syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropeptides 2016, 56, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti, A.L.; Hood, S.D.; Drummond, P.D. Multiple antidepressant potential modes of action of curcumin: A review of its anti-inflammatory, monoaminergic, antioxidant, immune-modulating and neuroprotective effects. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 26, 1512–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, R.; Zimmermann, C.; Drewe, J.; Hoexter, G.; Zahner, C. Dose-dependent efficacy of the Vitex agnus castus extract Ze 440 in patients suffering from premenstrual syndrome. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2012, 19, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Lucky, A.W. Quantitative documentation of a premenstrual flare of facial acne in adult women. Arch. Dermatol. 2004, 140, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, L.; Rosen, J.; Frankel, A.; Goldenberg, G. Perimenstrual Flare of Adult Acne. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Telkkälä, A.; Sinikumpu, S.P.; Huilaja, L. Etiology of Adult Female Acne–Systematic Review. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani, N.; Rezaei, F.; Zare Mirakabadi, A.; Mohaghegh Shalmani, L.; Farjam, M. A systematic review of N-acetylcysteine for treatment of acne vulgaris and acne-related associations and consequences: Focus on clinical studies. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.; Macdougall, M.; Brown, E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST) for clinicians. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2003, 6, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.S.; Obaideen, A.A.; Jahrami, H.A.; Radwan, H.; Hamad, H.J.; Owais, A.A.; Alardah, L.G.; Qiblawi, S.; Al-Yateem, N.; Faris, M.E.A.I.E. Premenstrual Syndrome Is Associated with Dietary and Lifestyle Behaviors among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Sharjah, UAE. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Die, M.D.; Burger, H.G.; Teede, H.J.; Bone, K.M. Vitex agnus-castus extracts for female reproductive disorders: A systematic review of clinical trials. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csupor, D.; Lantos, T.; Hegyi, P.; Benkő, R.; Viola, R.; Gyöngyi, Z.; Csécsei, P.; Tóth, B.; Vasas, A.; Márta, K.; et al. Vitex agnus-castus in premenstrual syndrome: A meta-analysis of double-blind randomised controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Lin, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Evaluating therapeutic effect in symptoms of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome with Vitex agnus castus (BNO 1095) in Chinese women. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 50, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayat, S.; Fanaei, H.; Kheirkhah, M.; Moghadam, Z.B.; Kasaeian, A.; Javadimehr, M. Curcumin attenuates severity of premenstrual syndrome symptoms: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, F.; Haghanifar, M.; Tarrahi, M.J. Assessment of N-acetylcysteine as an Alternative for the Treatment of the Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Pharm. Care 2019, 7, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, A.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Coppola, G.; Pierelli, F. Use of Vitex agnus-castus in migrainous women with premenstrual syndrome: An open-label clinical observation. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2013, 113, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meier, B.; Berger, D.; Hoberg, E.; Sticher, O.; Schaffner, W. Pharmacological activities of Vitex agnus-castus extracts in vitro. Phytomedicine 2000, 7, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichianpitaya, J.; Taneepanichskul, S. A Comparative Efficacy of Low-Dose Combined Oral Contraceptives Containing Desogestrel and Drospirenone in Premenstrual Symptoms. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013, 2013, 487143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, S. Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Symptoms and Cluster Influences. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cubeddu, A.; Bucci, F.; Giannini, A.; Russo, M.; Daino, D.; Russo, N.; Merlini, S.; Pluchino, N.; Valentino, V.; Casarosa, E.; et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor plasma variation during the different phases of the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbasi, S.; Seyedabadi, S.; Mozaffari, S.; Foroutan, Z.; Ferns, G.A.; Zarban, A.; Bahrami, A. Curcuminoid-Piperine Combination Improves Radical Scavenging Activity in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome and Dysmenorrhea: A Post-hoc Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Study. Chonnam Med. J. 2024, 60, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Ronnenberg, A.G.; Houghton, S.C.; Nobles, C.; Zagarins, S.E.; Takashima-Uebelhoer, B.B.; Faraj, J.L.; Whitcomb, B.W. Association of inflammation markers with menstrual symptom severity and premenstrual syndrome in young women. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Green, R.; Pak, S.C. N-Acetylcysteine for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Current Evidence. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2469486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Z.; Fu, Z.D.; Zhou, Y.B.; Zhou, L.F.; Yang, C.T.; Li, J.H. N-acetyl-L-cysteine reduces the ozone-induced lung inflammation response in mice. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2016, 68, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Tapia, A.; Eisman, A.B.; Barberá, J.F.; Jufresa, J.P.; Rodriguez, R.B. Comparative study of two dietary supplement inhibitors of 5α-reductase in female androgenic alopecia. Más Dermatol. 2018, 30, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.T.C.; Rodrigues, G.P. Serenoa Repens for the Treatment of Capillary Disorders. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2020, 32, 25022–25024. Available online: https://biomedres.us/fulltexts/BJSTR.MS.ID.005253.php (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.L.; Gao, Y.H.; Yang, J.Q.; Li, J.B.; Gao, J. Serenoa repens extracts promote hair regeneration and repair of hair loss mouse models by activating TGF-β and mitochondrial signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 4000–4008. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, L.F.; Wilborn, W.H.; Montes, C.M. Topical acne treatment with acetylcysteine: Clinical and experimental effects. Skinmed 2012, 10, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Webster, G.F.; Kligman, A.M. A method for the assay of inflammatory mediators in follicular casts. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1979, 73, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, G.F.; Leyden, J.J.; Tsai, C.C.; Baehni, P.; McArthur, W.P. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte lysosomal release in response to Propionibacterium acnes in vitro and its enhancement by sera from inflammatory acne patients. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1980, 74, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhvel, S.M.; Sakamoto, M. The chemoattractant properties of comedonal components. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1978, 71, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasi, F.; Page, C.; Rossolini, G.M.; Pallecchi, L.; Matera, M.G.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on biofilms: Implications for the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Respir. Med. 2016, 117, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Patient Values |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 32.2 ± 4.8 |

| Weight in pounds (mean ± SD) | 165.9 ± 39.8 |

| Weight in Kg (mean ± SD) | 75.2 ± 18.1 |

| Fitzpatrick Scale Rating | |

| Type 1 (%) | 15.4% |

| Type 2 (%) | 41.0% |

| Type 3 (%) | 35.9% |

| Type 4 (%) | 5.1% |

| Type 5 (%) | 2.6% |

| Parameter | % of Group Dermatologist Rated as Improved from Baseline (n) |

|---|---|

| Overall Skin Health | 91.18% (31) |

| Fine Lines/Wrinkles | 32.35% (11) |

| Dryness | 70.59% (24) |

| Background Redness | 64.71% (22) |

| Brightness | 82.35% (28) |

| Inflammation and Hormonal Acne | 41.18% (14) |

| How Much Do You Agree with the Following: | Cycle 1 (n = 37) | Cycle 2 (n = 37) | Cycle 3 (n = 36) | Cycle 4 (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My PMS symptoms are less severe since using this product. | 54.1% | 67.6% | 77.8% | 77.1% |

| My hormonal balance has improved since using this product. | 40.5% | 59.5% | 58.3% | 60.0% |

| My overall menstrual health has improved since using this product. | 45.9% | 64.9% | 63.9% | 74.3% |

| My well-being before and during my period has been better since using this product. | 56.8% | 73.0% | 72.2% | 68.6% |

| My hair health has improved since using this product. | 24.3% | 37.8% | 27.8% | 48.6% |

| My skin health has improved since using this product. | 32.4% | 48.6% | 50.0% | 54.3% |

| I have experienced less severe menstrual pain or cramps since using this product. | 59.5% | 64.9% | 75.0% | 68.6% |

| I have experienced less severe pelvic discomfort since using this product. | 51.4% | 64.9% | 80.6% | 71.4% |

| I have experienced less severe hormonal mood swings since using this product. | 45.9% | 64.9% | 63.9% | 65.7% |

| I have experienced less hormonal hair loss since using this product. | 24.3% | 37.8% | 36.1% | 42.9% |

| My hormonal bloating or fluid retention has reduced or resolved since using this product. | 35.1% | 43.2% | 55.6% | 60.0% |

| I have experienced less severe hormonal breast pain or tenderness since using this product. | 48.6% | 54.1% | 63.9% | 68.6% |

| I feel less irritable before and during my period since using this product. | 51.4% | 67.6% | 61.1% | 62.9% |

| I have experienced fewer episodes of crying or sadness before and during my period since using this product. | 56.8% | 59.5% | 61.1% | 71.4% |

| I am less prone to emotional distress before and during my period since using this product. | 45.9% | 62.2% | 63.9% | 68.6% |

| I would like to continue using this product. | - | - | - | 71.4% |

| I would purchase this product. | - | - | - | 62.9% |

| I would recommend this product to family and friends. | - | - | - | 71.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viña, I.; Viña, J.R. The Effects of FemmeBalance Supplement on Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Four-Cycle Single-Arm Observational Study of a Novel Nutritional Supplement. Life 2025, 15, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15091454

Viña I, Viña JR. The Effects of FemmeBalance Supplement on Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Four-Cycle Single-Arm Observational Study of a Novel Nutritional Supplement. Life. 2025; 15(9):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15091454

Chicago/Turabian StyleViña, Isabel, and Juan R. Viña. 2025. "The Effects of FemmeBalance Supplement on Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Four-Cycle Single-Arm Observational Study of a Novel Nutritional Supplement" Life 15, no. 9: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15091454

APA StyleViña, I., & Viña, J. R. (2025). The Effects of FemmeBalance Supplement on Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Four-Cycle Single-Arm Observational Study of a Novel Nutritional Supplement. Life, 15(9), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15091454